MARCH 2020

A Shortage of

Affordable Homes

The National Low Income Housing Coalition

1000 Vermont Avenue, NW • Suite 500

Washington, DC 20005

202-662-1530 • https://nlihc.org

© 2020 National Low Income Housing Coalition

ANDREW AURAND, PH.D., MSW

Vice President for Research

DAN EMMANUEL, MSW

Senior Research Analyst

DANIEL THREET, Ph.D.

Research Analyst

IKRA RAFI

Creative Services Specialist

DIANE YENTEL

President and CEO

ABOUT NLIHC

The National Low Income Housing Coalition is

dedicated solely to achieving socially just public policy

that ensures people with the lowest incomes in the

United States have affordable and decent homes.

Founded in 1974 by Cushing N. Dolbeare, NLIHC

educates, organizes and advocates to ensure decent,

affordable housing for everyone.

Our goals are to preserve existing federally assisted

homes and housing resources, expand the supply of low

income housing, and establish housing stability as the

primary purpose of federal low-income housing policy.

A Shortage of

Affordable Homes

NLIHC BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Marla Newman, Chair, Winston-Salem, NC

Dora Gallo, First Vice-Chair, Los Angeles, CA

Lot Diaz, Second Vice-Chair, Washington, DC

Moises Loza, Treasurer, Alexandria, VA

Martha Weatherspoon, Secretary, Clarksville, TN

Bob Palmer, At-Large Executive Committee, Chicago, IL

Dara Balwin, Washington, DC

Russell “Rusty” Bennett, Birmingham, AL

Emma “Pinky” Clifford, Pine Ridge, SD

Yanira Cortes, Resident, Toms River, NJ

Chris Estes, Washington, DC

Daisy Franklin, Resident, Norwalk, CT

Deirdre “DeeDee” Gilmore, Charlottesville, VA

Aaron Gornstein, Boston, MA

Erhard Mahnke, Burlington, VT

Rachael Myers, Seattle, WA

Karlo Ng, San Francisco, CA

Ann O’Hara, Boston, MA

Crishelle Palay, Houston, TX

Eric Price, Washington, DC

Shalonda Rivers, Opa Locka, FL

Nan Roman, Washington, DC

Michael Steele, New York, NY

NLIHC STAFF

Sonya Acosta Policy Analyst

Jordan April Research Intern

Kyle Arbuckle Housing Advocacy Organizer

Andrew Aurand Vice President for Research

Victoria Bourret Housing Advocacy Organizer

Alayna Calabro Field Intern

Josephine Clarke Executive Assistant

Dan Emmanuel Senior Research Analyst

Ed Gramlich Senior Advisor

Paul Kealey Chief Operating Ofcer

Mike Koprowski Director, Multisector Housing

Campaign

Joseph Lindstrom Director for Field Organizing

Kim Johnson Policy Analyst

Mia Juliana Graphic Design/Communications

Intern

May Louis-Juste Communications Specialist

Lisa Marlow Manager of Media Relations and

Communications

Sarah Saadian Vice President for Public Policy

Khara Norris Director of Administration

Noah Patton Housing Policy Analyst

Ikra Ra Creative Services Specialist

Tyra Reed Policy Intern

Catherine Reeves Development Coordinator

Brooke Schipporeit Housing Advocacy Organizer

Daniel Threet Research Analyst

Chantelle Wilkinson Multisector Housing Campaign

Coordinator

Renee Willis Vice President for Field and

Communications

Diane Yentel President and CEO

MARCH 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ..............................................1

Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes .......................2

Affordable, but Not Available ..............................4

Housing Cost Burdens .....................................6

The Housing Shortage for Extremely

Low-Income Renters by State...............................8

The Housing Shortage for Extremely

Low-Income Renters in the 50 Largest Metros ................9

Who Are Extremely

Low-Income Renters?.....................................11

Racial Disparities and Extremely Low-Income Renters ........13

A Systemic National Shortage of Rental

Housing for Extremely Low-Income Households .............15

Federal Policy Solutions for the Lowest-Income People .......17

Housing Justice..........................................19

Conclusion ..............................................20

About the Data ..........................................21

For More Information.....................................21

References ..............................................22

Appendix A: State Comparisons ...........................25

Appendix B: Metropolitan Comparisons ....................26

Made Possible By The Generous Support Of

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

1

T

he last few years have seen the lowest

unemployment rate in 50 years, new stock

market records, and increasing weekly

earnings for full-time workers (Bureau of Labor

Statistics, 2019; Phillips, 2020; Bureau of Labor

Statistics, 2020). e benets of economic growth,

however, are unevenly distributed: income inequality

continues to grow, 44% of workers aged 18-64 are

in low-wage jobs, more than 38 million Americans

remain in poverty, and homelessness has increased

by 3% since 2018 (Guzman, 2019; Ross &

Bateman, 2019; Semega et al., 2019; HUD, 2020).

Improvements in the economy have not resolved

the longstanding needs of low-income people who

continue to struggle to nd aordable, decent,

and accessible housing. e supply of aordable

housing for the nation’s lowest-income families and

individuals remains deeply inadequate.

Each year, NLIHC examines the American

Community Survey (ACS) to determine the

availability of rental homes aordable to extremely

low-income households – those with incomes at or

below the poverty line or 30% of the area median

income (AMI), whichever is greater – and other

income groups (Denitions). is annual report

provides information on aordable housing for the

U.S., each state plus the District of Columbia (DC),

and the largest metropolitan areas. is year’s key

ndings include:

• 10.9 million renter households with extremely

1 We use ‘renters’ and ‘renter households’ interchangeably to refer to renter households throughout this report.

low incomes account for 25% of all renter

households and 8% of all U.S. households.

• Extremely low-income renters in the U.S. face

a shortage of 7 million aordable and available

rental homes. Only 36 aordable and available

homes exist for every 100 extremely low-income

renter households.

1

• Seventy-one percent (7.7 million) of the nation’s

10.9 million extremely low-income renter

households are severely housing cost-burdened,

spending more than half of their incomes on

rent and utilities. ey account for almost 72%

of all severely cost-burdened renters in the U.S.

• Extremely low-income renters are much more

likely to be severely housing cost-burdened than

other income groups. irty-three percent of

very low-income, eight percent of low-income,

and two percent of middle-income renters are

severely cost-burdened.

• Extremely low-income renters are more likely

than other renters to be seniors or people with

disabilities. Forty-six percent of extremely low-

income renter households are seniors or disabled,

and another 44% are in the labor force, in school,

or single-adult caregivers.

• People of color are more likely than white

people to be extremely low-income renters.

Twenty percent of Black households, 17% of

American Indian or Alaska Native households,

15% of Hispanic households, and 10% of Asian

households are extremely low-income renters.

INTRODUCTION

DEFINITIONS

AREA MEDIAN INCOME (AMI): The median family income in the metropolitan or nonmetropolitan area

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME (ELI): Households with incomes at or below the poverty guideline or 30% of AMI, whichever is higher

VERY LOW-INCOME (VLI): Households with incomes between ELI and 50% of AMI

LOW-INCOME (LI): Households with incomes between 51% and 80% of AMI

MIDDLE-INCOME (MI): Households with incomes between 81% and 100% of AMI

ABOVE MEDIAN INCOME: Households with incomes above 100% of AMI

COST BURDENED: Spending more than 30% of household income on housing costs

SEVERELY COST BURDENED: Spending more than 50% of household income on housing costs

2

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

Only 6% of white non-Hispanic households are

extremely low-income renters.

• Black households account for 12% of all

households in the United States and 19% of

all renters, but they account for 26% of all

renter households with extremely low incomes.

Likewise, Hispanic households account for 12%

of all households, 19% of all renter households,

and 21% of all renter households with extremely

low incomes.

• No state has an adequate supply of aordable

and available homes for extremely low-income

renters. e current relative supply ranges from

18 aordable and available homes for every 100

extremely low-income renter households in

Nevada to 62 in West Virginia.

• e shortage of aordable homes ranges from

8,200 in Wyoming to nearly one million in

California.

Housing is a fundamental need, yet millions of

extremely low-income renters cannot aord a place

to live. e private market consistently fails to meet

the housing needs of the lowest-income families.

What extremely low-income renters can aord to

pay will not cover the development and operating

costs of new housing developments, and in many

cases, it will not even meet the rents demanded

from landlords to maintain older housing. A family

of four with poverty-level income could aord a

monthly rent of no more than $644 in 2019 without

housing assistance. e average cost of a modest

two-bedroom rental home at the fair market rent,

however, was $1,194 (NLIHC, 2019a).

While the private market has never been able to

produce an adequate supply of homes for extremely

low-income households, the growth of low-wage

work exacerbates the problem. Seven of the ten

occupations projected to experience the greatest

growth over the next decade provide median

hourly wages that are insucient for full-time

workers to aord modest apartments (NLIHC,

2 e 30% standard is commonly used to estimate the scope of housing aordability problems and serves as the basis for some administrative policies, but some

households may struggle even at this level of housing cost (Stone, 2006).

2019a). Meanwhile, Congress consistently provides

insucient funding for federal housing assistance:

three out of four low-income households in need

of and eligible for federal housing assistance receive

none (Fischer & Sard, 2017).

e lowest-income families are often forced to

make impossible choices between shelter and food,

healthcare, education, and other basic needs. is

deprivation is severe, predictable, and avoidable;

not addressing it is a failure of will and an injustice.

Access to a stable, decent, aordable, and accessible

home is essential to virtually every area of a person’s

life. Housing is intrinsically connected to better

health outcomes (Bailey, 2020), economic mobility

(Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2015), employment

prospects (Desmond & Gershenson, 2016), and

greater opportunities for people exiting the criminal

justice system (Couloute, 2018).

A large-scale, sustained commitment to aordable

housing for people with the lowest incomes, through

such programs as the national Housing Trust Fund

(HTF), Housing Choice Vouchers (HCVs), and

public housing, can correct for the failures of the

market and achieve housing justice.

A SEVERE SHORTAGE OF

AFFORDABLE RENTAL HOMES

Over 10.9 million of the nation’s 43.7 million renter

households have extremely low incomes. Only 7.3

million rental homes are aordable to extremely

low-income renters, assuming households should

spend no more than 30% of their incomes on

housing.

2

is supply leaves an absolute shortage of

3.6 million aordable rental homes. Extremely low-

income renters are the only income group facing this

absolute shortage of aordable homes.

e shortage does not account for the 568,000

people who are experiencing homelessness, as the

ACS includes only households with an address

(HUD, 2020). Taking into account the number

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

3

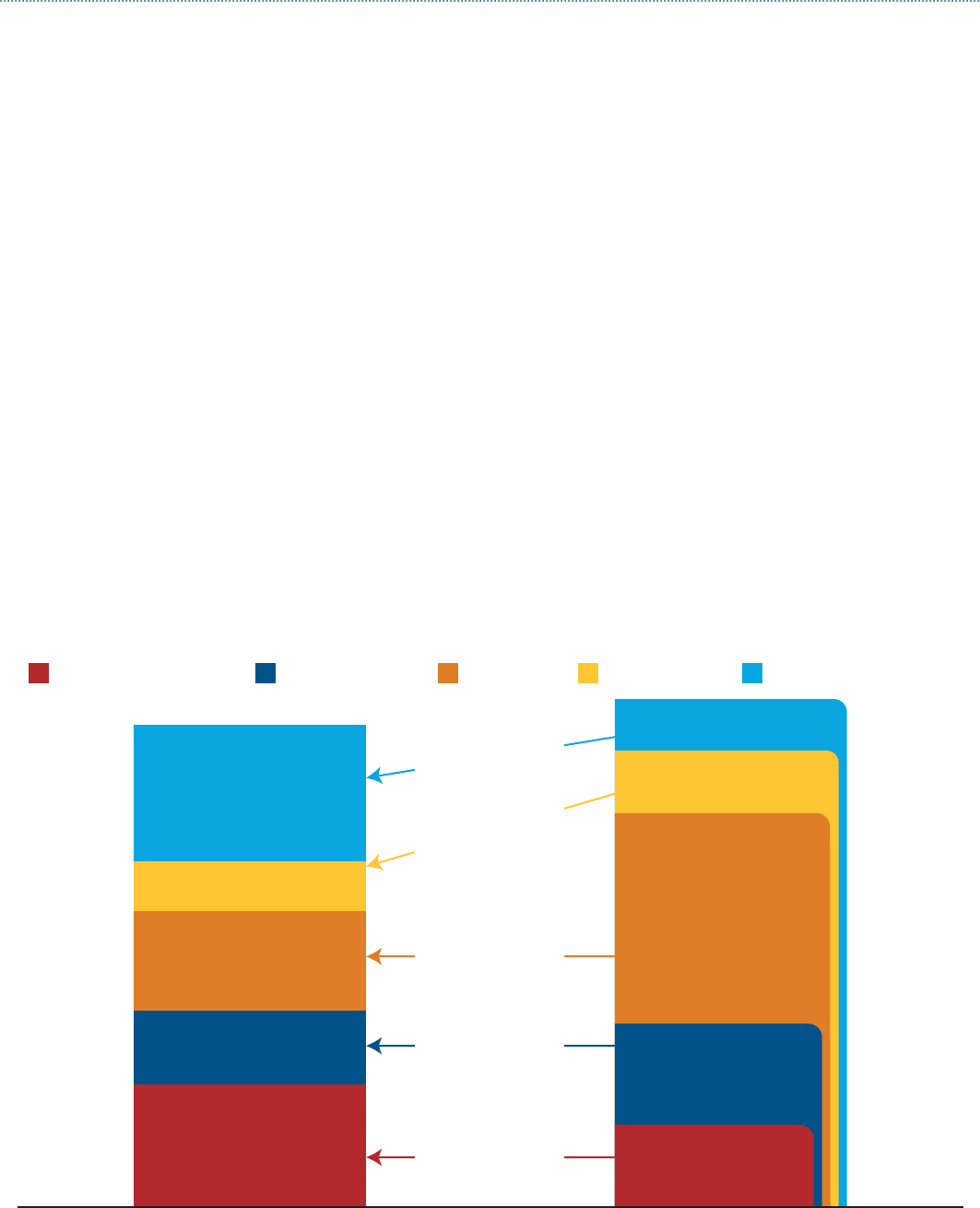

FIGURE 1: RENTAL UNITS AND RENTERS IN THE US, MATCHED BY

AFFORDABILITY AND INCOME CATEGORIES, 2018 (IN MILLIONS)

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data.

Households

(By Income Category)

10.9m Households

6.8m Households

9.0m Households

4.5m Households

12.5m Households

AFFORDABLE

AFFORDABLE

AFFORDABLE

AFFORDABLE

AFFORDABLE

Cumulative Units

(By Affordability Category)

46m Units

41.2 + 4.8 =

41.2m Units

35.4 + 5.8 =

35.4m Units

16.2 + 19.2 =

16.2m Units

7.3 + 8.9 =

7.3m Units

Extremely Low-Income Very Low-Income Low-Income Middle-Income Above Median Income

of people experiencing homelessness in families,

another 449,737 homes are needed. e real

shortage of rental homes aordable to extremely

low-income households, therefore, is closer to 4.1

million. Even this estimate is conservative, as it does

not account for doubled-up households.

In contrast, there is a cumulative surplus of

aordable homes for households with higher

incomes (Figure 1). Approximately 6.8 million

renter households have very low incomes (i.e.,

incomes above the extremely low-income threshold

but below 50% of AMI). Members of that income

group can aord the same 7.3 million rental homes

that are aordable to extremely low-income renters,

and they can also aord another 8.9 million more

expensive rental homes. In total, 16.2 million rental

homes are aordable for the 6.8 million very low-

income renter households. A cumulative shortage

remains, however, when we consider both extremely

low- and very low-income renter households

together.

Nine million renters have low incomes (i.e.,

incomes between 51% and 80% of AMI). Low-

income renters can aord the 16.2 million homes

aordable to extremely low-income and very low-

income renters, and they can aord an additional

19.2 million more expensive rental homes. In total,

35.4 million rental homes are aordable to low-

income renters. Approximately 4.5 million renters

are middle-income (i.e., with incomes between 81%

and 100% of AMI). Middle-income renters can

aord all the homes that low-income renters can

aord, plus an additional 5.8 million more expensive

rental homes, so the total supply of aordable rental

housing for that group is 41.2 million units.

4

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

AFFORDABLE, BUT NOT

AVAILABLE

In the private market, households are free to occupy

homes that cost less than 30% of their incomes,

and many do. When higher-income households

occupy rental homes that are also aordable to

lower-income households, they render those homes

unavailable to the lower-income households.

Extremely low-income renters must compete

with all higher-income households for the limited

number of units aordable to them in the private

market. An analysis of housing aordability,

therefore, cannot stop at the shortage of homes

aordable to renters with extremely low incomes; it

must also account for the fact that higher-income

renters are occupying some of the most aordable

units. Rental homes are both aordable and

available for households of a specic income group

if the homes are aordable to them and are currently

vacant or are occupied by households with incomes

at their income level.

Of the 7.3 million homes aordable to extremely

low-income households, approximately one million

are occupied by very low-income households, one

million are occupied by low-income households,

400,000 are occupied by middle-income households,

and 900,000 are occupied by households with above-

median incomes. Consequently,

only four million homes that rent

at aordable prices for extremely

low-income renters are available

to them. at leaves a shortage

of seven million aordable and

available homes for renters with

extremely low incomes. Many

extremely low-income households

are consequently forced to rent

homes they cannot aord – 23%

are in homes aordable to very

low-income households, 33%

are in homes aordable to low-

income households, 7% are in

homes aordable to middle-

income households, and 4% are in homes aordable

to households with above-median incomes.

e relative supply of aordable and available rental

homes improves as incomes increase. Only 36 rental

homes are aordable and available for every 100

extremely low-income renter households (Figure 2).

Fifty-seven exist for every 100 renter households

with incomes at or below 50% of AMI. Ninety-three

and 101 aordable and available rental homes exist

for every 100 renter households earning at or below

80% and 100% of AMI, respectively.

e shortage of aordable and available rental

homes for renters with incomes over 50% of AMI

can be explained by the shortage of aordable and

available rental homes for those with incomes below

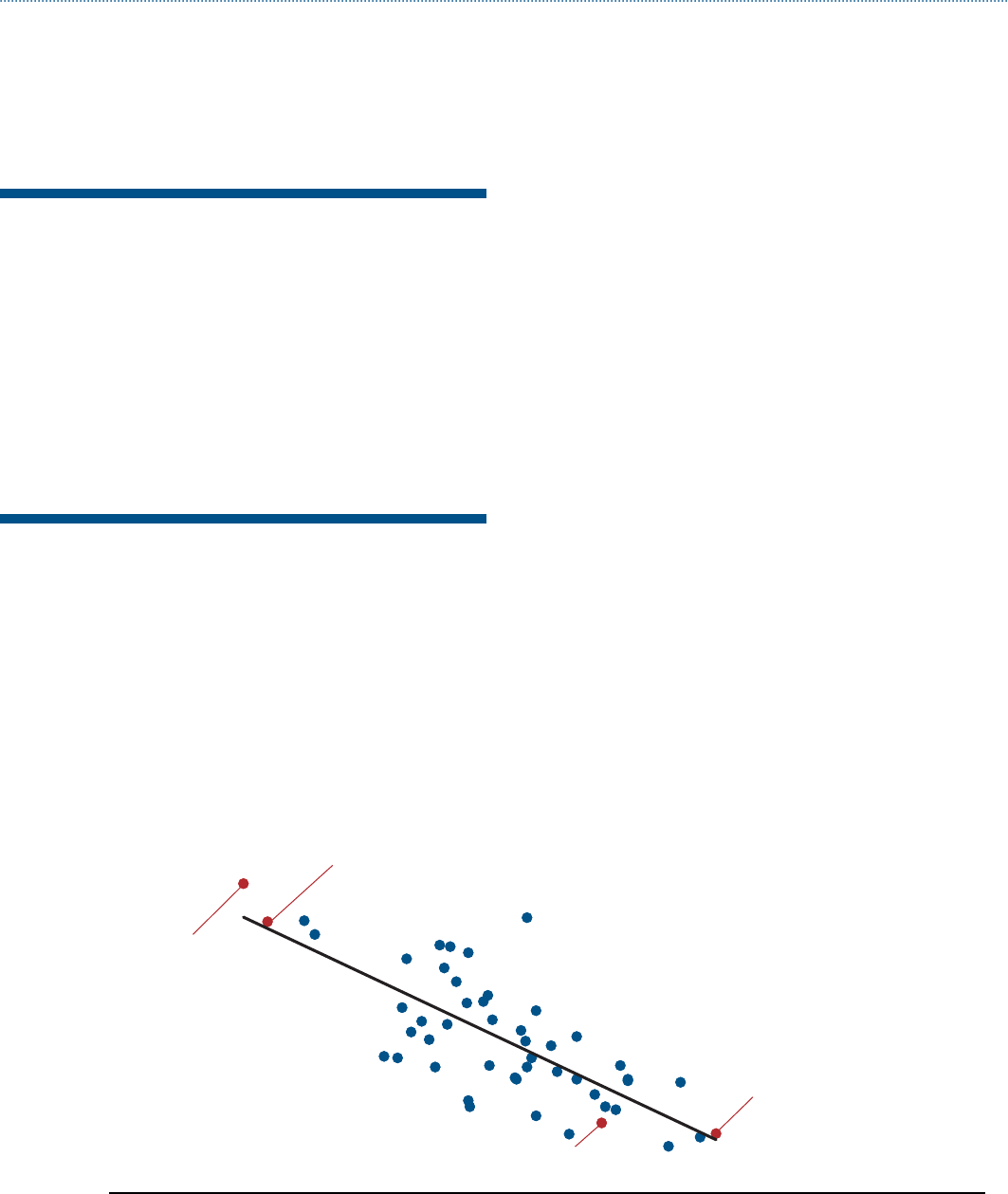

FIGURE 2: AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE RENTAL

HOMES PER 100 RENTER HOUSEHOLDS, 2018

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data. AMI = Area Median Income

101

93

57

36

At 100% AMI

At 80% AMI

At 50% AMI

At Extremely

Low-Income

Extremely low-income

renters must compete

with all higher-income

households for the

limited number of units

affordable to them in

the private market.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

5

FIGURE 3: RENTER HOUSEHOLDS AND AFFORDABLE

& AVAILABLE RENTAL HOMES, 2018

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data.

Incremental Increase in Households

Incremental Increase in Affordable & Available Rental Homes

Household Income

10.9

4.0

6.8

6.2

9.0

14.8

< 80% AMI

10.9

4.0

6.8

6.2

< 50% AMI

10.9

4.0

6.8

6.2

9.0

14.8

4.5

6.7

< 100% AMI

10.9

4.0

6.8

6.2

9.0

14.8

4.5

6.7

12.5

14.4

Above Median

Income

10.9

4.0

At Extremely

Low-Income

50% of AMI. Figure 3 illustrates the incremental

change in the cumulative number of renters at

increasingly higher levels of income, alongside the

cumulative number of rental homes aordable and

available. e gure shows

a cumulative shortage of

aordable and available

rental homes at lower

levels of income and a

surplus at higher levels.

Represented on the far

left of Figure 3, 10.9

million extremely low-

income renter households

occupy or have access to

only 4 million aordable

and available units, leaving a shortage of nearly

7 million rental homes. Moving to the right to

include all renter households earning up to 50%

of AMI, there is an incremental increase of 6.8

million households, but the number of aordable

and available rental homes increases only by 6.2

million units. Consequently, there is a shortage of

7.5 million aordable and available rental homes for

households with incomes at or below 50% of AMI.

e shortage decreases

as incomes rise. Going

further up the income

scale to include all

renters earning less

than 80% of AMI adds

9 million households

to the cumulative total

of renter households,

and it adds 14.8 million

units to the cumulative

total of aordable and available rental homes.

is incremental increase signicantly reduces the

cumulative shortage of aordable and available

rental homes. At median income, the cumulative

shortage disappears.

The figure shows a

cumulative shortage

of affordable and

available rental homes

at lower levels of

income.

6

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

e bars in Figure 4 illustrate the incremental

change in the cumulative decit and eventual

surplus of aordable and available rental homes

with each step up in income. Renters with extremely

low incomes face the most severe shortage by far,

and the cumulative shortages of homes available

and aordable for households with higher incomes

are largely attributable to the shortage for the

lowest-income renters. e dashed line shows the

cumulative decit or surplus of aordable and

available homes for all renters below

each income threshold. e cumulative

decit grows to 7.5 million aordable

and available homes for all renters with

incomes below 50% of AMI, but the

cumulative decit is only 1.7 million

for all renters with incomes below 80%

AMI because of the improvement

in supply for renters with incomes

between 51% and 80% of AMI.

HOUSING COST

BURDENS

Households are considered housing

cost-burdened when they spend more

than 30% of their incomes on rent and

utilities. ey are considered severely

cost-burdened when they spend more

than half of their incomes on their

housing. Cost-burdened households

have less to spend on other necessities,

such as food, clothing, transportation,

and healthcare. More than 9.3 million

extremely low-income renters, 5.2

million very low-income renters, and

4.1 million low-income renters are

cost-burdened (Figure 5). Combined,

extremely low-, very low-, and low-

income renters with incomes below

80% of AMI account for 92% of all

cost-burdened renters.

Of the 10.8 million severely housing

cost-burdened renter households, 7.7

million are extremely low-income,

FIGURE 4: INCREMENTAL CHANGE TO SURPLUS

(DEFICIT) OF AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE

RENTAL HOMES, 2018 (IN MILLIONS)

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data.

-8.0

-6.0

-4.0

-2.0

0

2.0

4.0

6.0

-7.0

-0.6

5.8

2.2

1.9

Extremely

Low-Income (ELI)

>ELI to 50%

of AMI

51% to 80%

of AMI

81% to 100%

of AMI

Above Median

-7.5

-1.8

0.4

Cumulative Deficit/Surplus

of Affordable and Available

Rental Homes

----

FIGURE 5: RENTER HOUSEHOLDS WITH COST

BURDEN BY INCOME GROUP, 2018

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS

9,376,471

7,745,633

Extremely

Low-Income

5,209,550

2,228,984

Very

Low-Income

4,140,459

705,088

Low-Income

928,264

89,717

Middle-Income

708,106

49,862

Above

Median Income

Cost Burden

Severe Cost Burden

Extremely low-income

renters account for

nearly 72% of all

severely cost-burdened

renters in the U.S.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

7

2.2 million are very low-income, 705,000 are low-

income, and 140,000 are middle- or higher-income.

Extremely low-income renters account for nearly

72% of all severely cost-burdened renters in the U.S

(Figure 6). Combined, extremely low-, very low-,

and low-income households account for nearly

99% of all severely cost-burdened renters. e other

1% of severely-cost burdened renters are largely

concentrated in high-cost or large metropolitan

areas. Just 10 metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, New

York, Miami, San Diego, Dallas, Houston, Chicago,

Phoenix, Tampa, and Atlanta) account for nearly

49% of all severely cost-burdened middle-income

and higher-income renters.

3

Los Angeles, New

York, and Miami themselves account more than

one-third of severely cost-burdened middle-income

and higher-income renters in the U.S.

3 ese same metropolitan areas account for 31% of all middle-income and higher-income renters.

4 e weighted average of 30% of HUD Median Family Income for HUD Fair Market Rent (FMR) areas (NLIHC, 2019a).

5 e weighted average of two-bedroom FMRs by FMR area (NLIHC, 2019a).

Extremely low-income renters have little, if any,

money remaining for other necessities after paying

their rent. A severely cost-burdened extremely

low-income family of four with monthly income

of $1,928,

4

for example, has $734 remaining for

all other non-housing expenses after renting the

average two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent

of $1,194.

5

e U.S. Department of Agriculture’s

thrifty food budget for a family of four (two adults

and two school-aged children) is $647 per month

(2019b), leaving only $87 for transportation, child

care, and all other necessities.

Severely housing cost-burdened, poor renters make

signicant sacrices to pay for housing. In 2017,

poor families with children who were severely

cost-burdened spent just $310 per month on

food, roughly half the cost of the most minimal

food plan recommended by the

U.S. Department of Agriculture

for families. Severely cost-

burdened families also spend less

on healthcare, transportation,

and clothing ( Joint Center for

Housing Studies, 2019).

Even with these sacrices, severe

housing cost burdens make it

dicult for poor renters to keep

up with their rents. e 2017

American Housing Survey

reports that 1.9% of all renter

households were threatened with

eviction within the previous

three months. Among renters

with incomes under $30,000,

that share climbs to 2.7% ( Joint

Center for Housing Studies,

2020).

FIGURE 6: SEVERELY HOUSING COST-BURDENED

RENTERS BY INCOME, 2018

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS

Extremely

Low-Income

71.6%

Very Low-Income

20.6%

Low-Income

6.5%

Middle-Income

0.8%

Above

Median Income

0.5%

8

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

THE HOUSING SHORTAGE FOR

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

RENTERS BY STATE

No state has an adequate supply of rental housing

aordable and available for extremely low-

income households (Figure 7 and Appendix A).

e shortage ranges from 8,201 rental homes in

Wyoming to nearly one million in California. e

states where extremely low-income renters face the

greatest challenges in nding aordable homes are

Nevada, with only 18 aordable and available rental

homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter

households, California (23 for every 100 extremely

low-income renter households), Arizona (26/100),

Florida (26/100), and Oregon (28/100). e states

with the greatest relative supply of aordable and

available rental homes for extremely low-income

renters still have signicant shortages. e ve top

states are West Virginia, with 62 aordable and

available rental homes for every 100 extremely

low-income renter households, Alabama (56/100),

Mississippi (55/100), Kentucky (53/100), and

Arkansas (52/100).

A majority of extremely low-income renters are

severely housing cost-burdened in every state. e

states with the greatest percentage of extremely

low-income renter households with severe cost

burdens are Nevada (81%), Florida (79%), California

FIGURE 7: RENTAL HOMES AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE

PER 100 EXTREMELY LOW INCOME RENTER HOUSEHOLDS BY STATE

Note: Extremely low income (ELI) renter households have incomes at or below the poverty level or 30% of the area median

income. Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS Data.

ME

51

NH

39

MA–48

CT–41

NY

36

PA

38

NJ–29

DE–36

MD–34

VA

36

WV

62

OH

44

IN

38

MI

40

IL

36

WI

33

MN

41

IA

46

MO

42

AR

52

LA

42

TX

29

OK

45

KS

41

NE

37

ND

51

SD

49

MT

39

ID

44

WA

31

OR

28

CA

23

AK

29

HI

39

WY

50

CO

31

UT

31

NV

18

AZ

26

NM

46

NC

43

TN

47

KY

53

SC

47

GA

41

AL

56

MS

55

FL

26

RI–51

VT

42

DC–41

30 or Fewer

Between 31 and 40

Between 41 and 45

More than 45

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

9

(77%), Delaware (76%), New Jersey (74%), and

Oregon (74%). Rhode Island has the smallest, but

still signicant, percentage of extremely low-income

renters with severe cost burdens (55%).

e state shortages of aordable and available

rental homes disappear for households higher up

the income ladder. Forty-nine states and DC have

a cumulative shortage of aordable and available

rental homes for renters with household incomes

below 50% of AMI. Eighteen states and DC have a

cumulative shortage for all renters with household

incomes below 80% of AMI. In eight states with

high-cost metropolitan regions—California, Florida,

Hawaii, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York,

Oregon, and Washington—there is a cumulative

shortage for all renters with household incomes up

to the median income.

THE HOUSING SHORTAGE FOR

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

RENTERS IN THE 50 LARGEST

METROS

Every major metropolitan area in the U.S. has a

shortage of aordable and available rental homes

for extremely low-income renters (Table 1 and

Appendix B). Of the 50 largest metropolitan areas,

extremely low-income renters face the most severe

shortages in Las Vegas, NV, and Austin, TX, with 14

aordable and available rental homes for every 100

extremely low-income renter households, Riverside,

CA (18/100), Phoenix, AZ (18/100), and San

Diego, CA (19/100).

Of the 50 largest metropolitan areas, those with the

least severe shortages of rental homes aordable

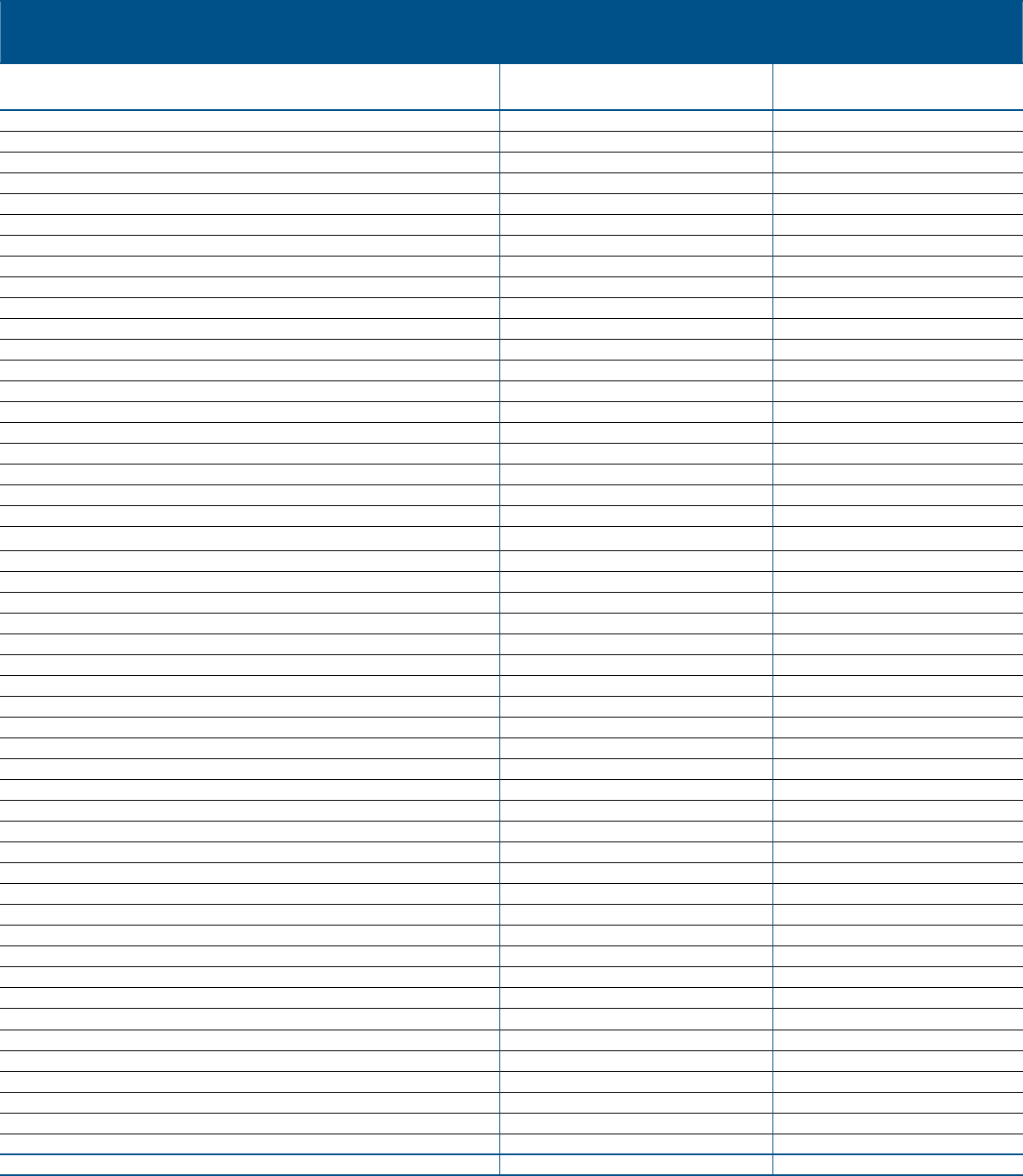

TABLE 1: LARGE METROPOLIAN AREAS WITH THE LEAST AND MOST SEVERE

SHORTAGES OF RENTAL HOMES AFFORDABLE TO EXTREMELY LOW INCOME

HOUSEHOLDS

LEAST SEVERE MOST SEVERE

Metropolitan Area

Affordable and

Available Rental

Homes per 100 Renter

Households

Metropolitan Area

Affordable and

Available Rental

Homes per 100 Renter

Households

Providence-Warwick, RI-MA 54 Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV 14

Pittsburgh, PA 51 Austin-Round Rock, TX 14

Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH 47 Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA 18

Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls, NY 42 Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ 18

Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT 41

San Diego-Carlsbad, CA

19

Cleveland-Elyria, OH 41 Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land, TX 19

Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, MD 40 Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL 20

Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin, TN

40 Sacramento-Roseville-Arden-Arcade, CA 20

Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN 39 Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA 20

San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX 38 Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX 21

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data.

No state has an

adequate supply

of rental housing

affordable and available

for extremely low-

income households.

10

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

and available to extremely low-income renters are

Providence, RI, with 54 for every 100 extremely

low-income renter households, Pittsburgh, PA

(51/100), Boston, MA (47/100), Bualo, NY

(42/100), and Hartford, CT (41/100).

Each of the 50 largest metropolitan areas has a

shortage of rental homes aordable and available

for renters with household incomes below 50% of

AMI. e shortages begin to disappear at higher

incomes. irty of the 50 largest metropolitan

areas have a cumulative shortage of aordable and

available rental homes for all renters with household

incomes up to 80% of AMI. Only 11 of them have

a cumulative shortage for all renters with household

incomes up to the median income. Unsurprisingly,

more than 90% of renters with extremely low

incomes are cost-burdened in eight of the ten

metropolitan areas with the most severe shortages

of aordable and available homes. In seven of those

metropolitan areas, at least 80% of renters with

extremely low incomes were severely cost-burdened.

A signicant factor in explaining these severe

housing cost burdens is the lack of subsidized

aordable housing for extremely low-income

households. Figure 8 shows that metropolitan

areas with less HUD-assisted housing as a share

of the total rental stock have a greater share of

extremely low-income renters who are severely

cost-burdened. HUD assistance includes public

housing, Housing Choice Vouchers, and project-

based rental assistance. is relationship exists even

after considering rental vacancy rates, the share of

rental housing in multifamily buildings, and the age

of the housing stock. In Boston, 59% of extremely

FIGURE 8: HUD-ASSISTED SHARE OF RENTAL STOCK AND SHARE OF

SEVERELY COST-BURDENED RENTER HOUSEHOLDS IN TOP 50 METROS

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS and HUD Picture of Subsidized Households data.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

50% 60% 70% 80%90% 100%

R²= 0.566

Boston

Las Vegas

Houston

Providence

HUD-Assisted Share of Rental Stock

Severely Cost-Burdened Share of ELI Renter Households

A significant factor in

explaining these severe

housing cost burdens is

the lack of subsidized

affordable housing for

extremely low-income

households.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

11

low-income renter households are severely cost-

burdened, while HUD-assisted rental housing

represents a relatively high share of the rental stock

at 18%. Massachusetts also operates its own state-

funded public housing programs, which provide over

28,000 additional subsidized units in the Boston

metropolitan area (Massachusetts Department of

Housing and Community Development, 2020).

In Providence, RI, 57% of extremely low-income

renter households are severely cost-burdened,

while HUD-assisted housing represents 20% of

the rental housing stock. In comparison, 86% of

extremely low-income renters are severely cost-

6 A disabled household is one whose householder and householder’s spouse (if applicable) are younger than 62 and at least one of them has a disability. A senior

household is one whose householder or householder’s spouse (if applicable) is at least 62 years of age.

burdened in the Las Vegas metropolitan area, where

HUD-assisted housing represents 4% of the rental

housing stock. Seventy-nine percent of extremely

low-income renters are severely cost-burdened in

Houston, where HUD-assisted housing represents

5% of the rental stock.

WHO ARE EXTREMELY LOW-

INCOME RENTERS?

Renters with special needs and senior renters are

more likely than other renters to have extremely

low incomes. Twenty-ve percent of all renter

households have extremely low incomes, but 43% of

renter households who are disabled and 34% who

are senior renter households have extremely low

incomes.

6

As a group, extremely low-income renters

are more likely than the general renter population to

be at least 62 years old or to have a disability

(Figure 9).

e vast majority of extremely low-income renters

work in low-wage jobs or are unable to work. irty-

seven percent of extremely low-income renter

households are in the labor force, while 28% are

47% 27% 3% 6% 18%

26% 28% 5% 13% 28%

Non-disabled, non-elderly without children Non-disabled, non-elderly with children Disabled with children Disabled Senior

All Other Renter Households

Extremely Low-Income Renter Households

FIGURE 9: HOUSEHOLD TYPE BY INCOME

Note: Senior means householder or householder’s spouse is at least 62 years of age, regardless of children in the house-

hold. Disabled means householder and householder’s spouse (if applicable) are younger than 62 and at least one of them

has a disability. Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data.

Renters with special

needs and senior

renters are more likely

than other renters to

have extremely low

incomes.

12

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

seniors, 18% have a householder with a disability,

and another 7% are students or single-adult

caregivers to a young child or household member

with a disability (Figure 10).

Seventy-seven percent of extremely low-income

households in the labor force work more than 20

hours per week, but low-wage employment does not

provide them adequate income to aord housing.

e national average of what a full-time worker,

working 40 hours per week for 52 weeks of the year,

needs to earn to aord a modest one-bedroom or

two-bedroom apartment is $18.65 or $22.96 per

hour, respectively (NLIHC, 2019a). A recent report

from Brookings nds that 53 million people are

“low-wage workers,” with a median hourly wage

of $10.22. Nearly half of this group works in retail

sales, food preparation, building cleaning, personal

care, construction, or driving (Ross & Bateman,

2019). Low-wage employment will continue to

grow. Seven of the ten occupations projected to

add the most jobs over the next decade, including

medical assistants, home health aides, janitors, and

food servers, provide a median wage that is lower

than what is needed for a full-time worker to aord

modest rental housing (NLIHC, 2019a).

More than 14% of extremely low-income renters

are single-adult caregivers of a young child or of a

household member with a disability. More than half

FIGURE 10: EXTREMELY LOW INCOME RENTER HOUSEHOLDS

Note: Mutually exclusive categories applied in the following order: senior, disabled, in labor force, enrolled in school, single

adult caregiver of a child under 7 or of a household member with a disability, and other. Senior means householder or house-

holder’s spouse (if applicable) is at least 62 years of age. Disabled means householder and householder’s spouse (if applicable)

are younger than 62 and at least one of them has a disability. Working hours is usual number of hours worked by householder

and householder's spouse (if applicable). School means householder and householder's spouse (if applicable) are enrolled in

school. Fifteen percent of extremely low-income renter households include a single adult caregiver, more than half of whom

usually work more than 20 hours per week. Eleven percent of extremely low-income renter households are enrolled in school,

48% of whom usually work more than 20 hours per week. Source: 2018 ACS PUMS.

Single non-disabled non-elderly caregiver

of person w/ disability or young child

3%

School

4%

40+ hours / week

20 to 39 hours / week

< 20 hours / week

Unemployed

Other

10%

Disabled

18%

Senior

28%

In Labor Force

37%

34%

43%

9%

14%

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

13

(53%) of these caregivers also participate in the labor

market. More than one quarter of these caregivers

work full-time, and another one quarter usually

work between 20 and 39 hours per week. Without

housing assistance or increases in their hourly wages,

they cannot rely on their work hours to aord their

homes.

RACIAL DISPARITIES AND

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

RENTERS

Black, Native American, and Hispanic households

are more likely than white households to be

extremely low-income renters. Twenty percent

of Black households, 17% of American Indian

or Alaska Native households, 15% of Hispanic

households, and 10% of Asian households are

extremely low-income renters. In contrast, only 6%

of white non-Hispanic households are extremely

low-income renters. is racial disparity is the

result of historical inequities and racist policies

and practices that have engendered higher

homeownership rates, greater wealth, and higher

incomes among white households. As Figure

11 illustrates, non-Hispanic white households

account for 65% of all U.S. households (including

homeowners and renters), 50% of all renters, and

43% of all extremely low-income renters. Black

households account for 12% of all households, yet

they account for 19% of all renters and 26% of all

extremely low-income renters. Hispanic households

account for 12% of all U.S. households, 19% of all

renters, and 21% of extremely low-income renters.

Decades of racial discrimination by real estate

agents, banks and insurers, and the federal

government made homeownership dicult to obtain

Black households

account for 12% of all

households, yet they

account for 26% of all

extremely low-income

renters.

FIGURE 11: RACIAL AND ETHNIC COMPOSITION BY HOUSING TYPE

Source: 2018 ACS PUMS.

All Households Renter Households

Extremely Low-Income

Renter Households

White, non-Hispanic Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian Other Interracial Couple

65%

12%

12%

4%

2%

5%

50%

19%

19%

5%

3%

4%

43%

21%

26%

5%

3%

1%

14

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

for people of color, and those disadvantages have

compounded over time. Many factors kept people

of color from being able to purchase homes through

the middle of the twentieth century: pervasive

refusal of whites to live in racially integrated

neighborhoods, physical violence to people of

color who tried to integrate (often tolerated by

the police), restrictive covenants forbidding sales

to minorities (some of which were mandated by

the Federal Housing Administration), and federal

housing policy that denied borrowers access to

credit in minority neighborhoods (Rothstein, 2017;

Coates, 2014). e prohibition of racially restrictive

covenants and racial discrimination in the sale,

rental, and nancing of housing has not rectied

the inequalities they created. People of color have

not beneted over time from the appreciation

in the value of the homes they were barred from

purchasing, which has expanded the wealth

gap and magnied inequalities of opportunity.

Housing discrimination plays a role in explaining

the profound racial disparities in wealth that exist

today—the wealth of the median white family is 12

times larger than the wealth of the median Black

family ( Jones, 2017). In a vicious cycle, the wealth

gap makes it harder for minority households to

invest in homeownership or help their children

purchase homes.

While overt discrimination was outlawed by

the Fair Housing Act, subtler forms of housing

discrimination continue to constrain the options of

people of color. Undercover testing on Long Island

from 2016 to 2019 found evidence that real estate

agents still steer minority homebuyers away from

white neighborhoods, avoid business in minority

neighborhoods, impose more stringent conditions

on minority buyers, and engage in other forms of

disparate treatment (Choi, Dedman, Herbert, &

Winslow, 2019). HUD’s fair housing test in 28

metropolitan areas across the country found that

Black homebuyers were shown 17.7% fewer homes

than white homebuyers with the same qualications

and preferences (HUD, 2013). Today’s credit scoring

system and lending practices also continue to serve

as barriers to minority homeownership (Rice &

Swesnik, 2012; Bartlett, Morse, Stanton, & Wallace,

2018).

Racial disparities in income are the result of

discrimination in hiring and setting wages,

dierences in employment rates, and other factors.

A recent review of discrimination studies found

that hiring discrimination continues to adversely

aect people of color. Whites receive on average

36% more callbacks than Blacks and 24% more

than Latinos (Quillian, Pager, Hexel, & Midtbøen,

2017). e same review found no decline in hiring

discrimination against Blacks over the past 25 years.

Recent wage growth has been racially unequal even

for people of the same education. Between 2015 and

2019, white workers with bachelor’s degrees have

seen their wages increase by 6.6%, but Black workers

with the same degrees have seen their wages decline

by 0.3% (Gould & Wilson, 2019). Black workers are

more likely than white workers to be underemployed

or unemployed at all education levels (Williams &

Wilson, 2019). In 2018, the median income of Black

and Hispanic households was 61% and 76% of the

median white household, respectively (Guzman,

2019).

Looking just at renters, one can see strong patterns

of racial inequality. People of color are more

likely to be extremely low-income renters: 35% of

American Indian renters, 34% of Black renters, 28%

of Hispanic renters, and 24% of Asian renters have

extremely low incomes, compared to 21% of white

non-Hispanic renters (Figure 12).

Across racial lines, the majority of extremely low-

income renters are severely housing cost-burdened:

70.5% of Hispanic, 70.9% of non-Hispanic Black,

Racial disparities in

income are the result of

discrimination in hiring

and setting wages,

differences in employment

rates, and other factors.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

15

and 70.5% of non-Hispanic white extremely low-

income renters pay more than half their incomes

for housing. Sixty percent of American Indian

extremely low-income renters are severely housing

cost-burdened, but poor housing conditions, low-

quality housing, and overcrowding are signicant

issues in tribal areas (Pindus et al., 2017).

A SYSTEMIC NATIONAL

SHORTAGE OF RENTAL

HOUSING FOR EXTREMELY LOW-

INCOME HOUSEHOLDS

e severe shortage of aordable homes for

extremely low-income renters is systemic, aecting

every state and metropolitan area. Absent public

subsidy, the private market is unable to produce

new rental housing aordable to these households,

because the rents that the lowest-income households

can aord to pay typically do not cover the

development costs and operating expenses of new

housing. New rental housing, therefore, is largely

targeted to the higher-price end of the market. e

average asking monthly rent in a new apartment

building in 2018 was $1,670, far higher than what

an extremely low-income renter household could

aord (Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2019).

e lack of new aordable rental construction

in the private market and insucient housing

assistance force extremely low-income renters to

rely on private-market housing that “lters down”

in relative price as it becomes older. e ltering

theory suggests that new market-rate development

for higher-income households results in a chain

of household moves that helps lower-income

households: Higher-income households move

into new, more expensive homes when they are

constructed, leaving behind their older housing.

Middle-income households move into the vacated

properties, leaving behind their own, even older

housing. is ltering process is assumed to

eventually increase the availability of older and

lower-priced housing for low-income renters.

e ltering process, however, fails to produce a

sucient supply of rental homes

inexpensive enough for the

lowest-income renters to aord.

In strong markets, owners have

an incentive to redevelop their

properties to receive higher rents

from higher-income households.

In weak markets, owners have an

incentive to abandon their rental

properties or convert them to

other uses when rental income is

too low to cover basic operating

costs and maintenance.

e rental market is signicantly

losing low-cost rental homes

while gaining high-cost ones.

Between 1990 and 2017, the

FIGURE 12: INCOME DISTRIBUTION OF RENTERS

BY RACE AND ETHNICITY

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data.

Some columns do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

35%

21%

9%

21%

American

Indian or

Alaska Native

34%

21%

9%

18%

Black,

non-Hispanic

28%

23%

10%

21%

Hispanic

21%

20%

11%

33%

Asian

16%

20%

12%

41%

White,

non-Hispanic

14% 17%

18%

15%

11%

Other or

Multiple

24%

15%

9%

39%

12%

Extremely Low-Income Very Low-Income Low-Income Middle-Income Above Median Income

The severe shortage of

affordable homes for

extremely low-income

renters is systemic,

affecting every state and

metropolitan area.

16

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

number of homes with monthly rents less than $600

in ination-adjusted terms declined by four million

(La Jeunesse et al., 2019). e number of rental

units priced below $600 per month fell by three

million in just ve years between 2012 and 2017.

Meanwhile, the number of rental homes renting for

more than $1,000 per month increased by more than

ve million during the same period ( Joint Center

for Housing Studies, 2020). Between the summers

of 2018 and 2019, only 12% of newly constructed

apartments had an asking price of less than $1,050

per month.

e systemic, national shortage of aordable

housing for extremely low-income renters is

evidence of the need for deeply income-targeted

federal housing subsidies to serve them. Public

subsidies are needed both to subsidize the

production and operation of aordable homes for

the lowest-income renters and to provide rental

assistance that low-income families can utilize to

aord rental housing in the private market.

Unlike those of extremely low-income renters, the

housing needs of middle-income renters are largely

met in most areas of the country.

e shortages of aordable and

available rental housing for

middle-income renters with

incomes above 80% of AMI are

predominantly found in high-

cost pockets of the country where

new housing development has

not kept pace with the growth in

demand. Eleven of the 50 largest

metropolitan areas (23 of the

largest 100) have a shortage of

homes aordable and available to

renters with household incomes

up to the median income.

Even in these housing markets,

however, the cumulative shortage

of aordable and available rental

homes is largely attributable to the

signicant unmet housing needs

of people with the lowest incomes who must occupy

rental homes in the private-market that would

otherwise be aordable and available to higher-

income renters. More than 760,000 extremely

low-income households occupy rental homes they

cannot aord that would otherwise be aordable

and available to middle-income renters (Figure 13).

Housing advocates and scholars across the

ideological spectrum agree that local zoning

and other requirements of the development

approval process can articially constrain housing

development and, in turn, limit the ability of the

private market to serve middle-income renters

(Axel-Lute, 2017; Jacobus, 2017). Reducing local

barriers to the production of multifamily housing

through reform of local zoning and upscale design

standards could result in a greater supply of housing

and alleviate rent pressures in the market for

households with moderate incomes. Zoning reform

could serve other laudable purposes, such as allowing

for more economic diversity in opportunity-rich

neighborhoods. Zoning reforms alone, however, will

not suciently improve the ability of extremely low-

FIGURE 13: EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTER

HOUSEHOLDS OCCUPYING UNITS AFFORDABLE

TO HIGHER INCOME GROUPS

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2018 ACS PUMS data. AMI = Area Median Income

2,506,566

Affordable to Very Low-Income

(30.1% - 50% of AMI)

3,612,741

Affordable to Low-Income

(50.1% - 80% of AMI)

764,601

Affordable to Middle-Income

(80.1% - 100% of AMI)

498,140

Above Median Income

(Over 100% of AMI)

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

17

income renters to aord the rents landlords need to

operate and adequately maintain housing.

FEDERAL POLICY SOLUTIONS

FOR THE LOWEST-INCOME

PEOPLE

e public and a growing number of congressional

leaders recognize the need for a signicant and

sustained federal commitment to housing programs

designed to meet the aordability needs of the

lowest-income families. Eighty-ve percent of

adults in a 2019 national poll believed that a safe,

decent, aordable place to live should be a national

priority, and 78% believed that government has

an important role to play in ensuring an adequate

supply of aordable homes, beliefs shared across

the political spectrum (Opportunity Starts at Home,

2019). e same poll found that 80% of adults

favored expanding federal housing programs to

ensure households with the lowest incomes and

greatest needs received rental assistance.

e solutions to the severe shortage of aordable

homes include the national Housing Trust Fund

(HTF), an annual block grant to states for the

creation, preservation, or rehabilitation of rental

housing for the lowest-income renters. e

distribution of HTF funds to each state and the

District of Columbia is determined by their shortage

of rental housing aordable and available to

extremely low-income and very low-income renters

and the extent to which these renters are severely

housing cost-burdened. At least 90% of HTF funds

must be used for rental housing and at least 75% of

the funds for rental housing must benet extremely

low-income households; 100% of HTF funds

must benet extremely low-income households

while the HTF is capitalized under $1 billion per

year. A review of the rst projects awarded HTF

money indicates the new program provides homes

for people experiencing homelessness, people with

disabilities, and seniors (NLIHC, 2018).

Members of the current Congress increasingly

support expanding the national HTF, having

introduced multiple bills to commit signicant

resources to do so. ese bills include the “American

Housing and Economic Mobility Act,” the “Ending

Homelessness Act,” the “Housing is Infrastructure

Act, ” the “Homes for All Act,” the “Fullling the

Promise of the Housing Trust Fund Act,” and the

“Pathway to Stable and Aordable Housing for All

Act.”

Expanding rental assistance programs, including the

Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, is also

gaining increased congressional support and must

also be a signicant component of any strategy to

address the severe housing shortage and instability

faced by extremely low-income renters. Seventy-ve

percent of current HCV recipients are extremely

low-income (HUD, 2019). Voucher recipients nd

rental housing in the private market and contribute

30% of their adjusted gross incomes toward housing

costs. e voucher pays the remaining costs up

to the local housing agency’s payment standard.

Vouchers typically cost less than new production,

making them an ecient and eective form of

housing assistance in markets with an abundant

supply of vacant, physically adequate housing that

the lowest-income renters cannot aord without

help. A ban on source-of-income discrimination

against voucher holders by landlords would improve

the eectiveness of this rental assistance.

e “Pathway to Stable and Aordable Housing

for All Act” would fully fund Housing Choice

The solutions to the severe

shortage of affordable

homes include the

national HTF, an annual

block grant to states for

the creation, preservation,

or rehabilitation of rental

housing for the lowest-

income renters.

18

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

Vouchers and the “Family Stability and Opportunity

Vouchers Act” would create an additional 500,000

housing vouchers designed specically to allow low-

income families with children to move into high-

opportunity neighborhoods. e Act would provide

counseling and case management services to help

voucher holders nd homes in neighborhoods with

high-performing schools, strong job prospects, and

other resources.

We also must protect the existing supply of

aordable homes for the poorest renters. Signicant

capital investment is needed for the rehabilitation

and preservation of public housing. Seventy-two

percent of households living in public housing

are extremely low-income, with the average

annual household income of public housing

residents at $15,738 (HUD, 2019). Public housing

provides a deep subsidy to these households: their

contributions toward rent are 30% of their adjusted

gross incomes, and a congressionally appropriated

Public Housing Operating Fund covers the

remaining operating costs. e Public Housing

Capital Fund is appropriated by Congress for capital

improvements and repairs, but decades of under-

funding have created a signicant backlog of capital

needs. e public housing stock may need as much

as $56 billion in repairs, which threatens the quality

and even the existence of these homes (NLIHC,

2019b).

Beyond protecting the existing supply of public

housing, we should work to expand it. e Faircloth

Amendment, which limits the total number of

public housing units to 1999 levels, should be

repealed. e “Housing is Infrastructure Act of

2019” would invest more than $100 billion to

address the capital needs of public housing, create

homes through the national HTF, and address the

severe housing needs on tribal lands. e “Homes

for All Act” would repeal the Faircloth amendment

and invest $1 trillion for 9.5 million new public

housing apartments and 2.5 million deeply

aordable rental homes.

Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) must

also be adequately funded for preservation. PBRA

consists of rental contracts between HUD and

private-property owners who provide subsidized

housing for low-income renters. Tenants contribute

30% of their adjusted gross income toward the rent,

and HUD’s contribution covers the rest. e average

annual income of households living in housing

supported by Section 8 PBRA is $13,301 (HUD,

2019). Without adequate and timely appropriations

to renew expiring contracts, some of these rental

homes could be lost from the aordable housing

stock. Sucient funds should also be appropriated

to preserve the aordable housing supported by

the USDA’s Section 515 loan program, whose

rural tenants have an annual household income of

$13,112 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019a).

Reforms to the federal tax code could also improve

our nation’s ability to stably house the poorest

renters. A deeply income-targeted, fully refundable

renters’ tax credit for housing cost-burdened renters

would help address the gap between housing costs

and the incomes of the lowest-income renters. e

credits could be based on the dierence between

30% of a renter’s household income and their actual

housing costs up to a modest price. e “Housing,

Opportunity, Mobility, and Equity Act” would

provide monthly tax credits to all cost-burdened

households for the dierence between 30% of their

income and the lesser of their monthly rent or the

small area fair market rent of their area. e “Rent

Relief Act” would also create a refundable tax credit

for cost-burdened renter households, targeted at

taxpayers earning less than $125,000 annually.

Congress should also expand and reform the Low

Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program

to better target the housing needs of extremely

low-income households. LIHTC is the largest

production subsidy for aordable housing in the U.S.

Beyond protecting the

existing supply of public

housing, we should work

to expand it.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

19

LIHTC rents, however, are not typically aordable

to extremely low-income renters without additional

rental assistance. NLIHC supports reforms to better

serve people with the lowest incomes, including a

50% basis boost in tax credits for developments that

set aside at least 20% of their housing for extremely

low-income renters. e “Aordable Housing Tax

Credit Improvement Act” would provide such a

basis boost, as well as incentives to build in rural

communities and on tribal lands, which have unique

barriers to development.

Congress should also create a National Housing

Stabilization Fund to provide emergency assistance

to low-income households facing housing instability,

eviction, or homelessness after an economic shock.

Modest temporary assistance could help households

stay in their homes after a short-term job loss or

unexpected emergency expense, reducing the long-

term negative impact of these events. e “Eviction

Crisis Act” would create such a fund (“Emergency

Assistance Fund”) to provide direct, short-term

nancial assistance and stability services to low-

income households facing eviction or homelessness.

S

table, decent, accessible housing is a

fundamental need. Housing provides

shelter, security, privacy, and a place for

sleep. Housing is instrumental, and in some

cases necessary, for hygiene, nutrition, and

health (Bratt, Stone, & Hartman, 2006). Housing

provides a space to cultivate and protect some

of the most important personal relationships

in our lives, with partners and family (Inness,

1992). Housing is an essential ingredient for

many elements of individuals’ well-being –

their health, control over their environment,

and the ability to develop their emotional lives,

plans, and connections to their community

(Nussbaum, 2011; Kimhur, 2020). When

housing is unaffordable, people are forced

to sacrice other essential needs or suffer

profound harms.

Decent, stable, and affordable homes

are a major social determinant of health.

When housing costs drive households into

poorer-quality housing, those households

are at greater risk of respiratory conditions,

injuries, and exposure to harsh temperatures,

pollutants, and allergenic triggers (Shaw,

2004). Families with housing cost burdens

or behind on rent are at greater risk of poor

health and higher maternal stress (Sandel

et al., 2018; Bills, West, & Hargrove, 2019).

Housing instability and homelessness can

cause signicant disruptions to critical

health services, especially for chronically ill

individuals, and increase adverse mental

health outcomes related to stress (Maqbool,

Viveiros, & Ault 2015).

Affordable homes are important for academic

achievement. Low-income children in

affordable housing score better on tests

of cognitive development than those in

unaffordable housing (Newman & Holupka,

2015; Newman & Holupka, 2014). Parents

who are no longer housing cost-burdened

can invest more in education and enrichment.

Affordable housing may allow families to

remain stably in place. Housing instability

can disrupt learning and negatively impact

academic achievement, especially among

elementary and middle-school students

(Brennan, Reed, Sturtevant, 2014; Herbers et

al., 2012; Voight, Shinn, & Nation, 2012).

Affordable housing can be a source of

economic opportunity. Stable housing is often

necessary for individuals to maintain steady

HOUSING JUSTICE

20

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

employment (Desmond & Gershenson, 2016).

When households are enabled to live in high-

opportunity neighborhoods, they have higher

annual incomes and higher lifetime earnings

(Chetty, Hendren, & Katz, 2015). Investments

in affordable housing can improve local

economies by creating jobs and attracting

families into the community (NLIHC, 2017).

The shortage of affordable and available

housing for people with extremely low

incomes is caused by structural features of

our social, political, and economic system,

not the personal failings of individuals. First,

a private housing market driven by economic

incentives will continually fail to meet the

needs of extremely low-income households.

Since it responds to opportunities for prot

rather than genuine housing need, private

industry will at best serve only a segment

of the population

with extremely low

incomes. Second, the

way in which income

and other resources

are distributed in our

society keeps a large

number of people in

poverty. What people earn in the labor market

is not determined simply by how hard they

work or what they deserve. The strength of

the economy, changing demands for different

kinds of talents, and labor’s weakening

bargaining power all play a signicant role in

determining wages (Olsaretti, 2004; Folbre,

2016). The labor market continues to create

low-wage work, and our political institutions

do not sufciently respond to the resulting

nancial needs of low-wage workers, leaving

many to struggle to afford basic needs.

In addition, the lack of adequate nancial

support for people outside the labor market –

for the elderly, people with disabilities, people

engaged in socially valuable but unpaid work

(such as caregivers), for example – increases

the numbers of people with low incomes

unable to afford their housing.

Features of our social, political, and economic

system also explain why certain groups in our

society—including Black people, Hispanics,

and Native Americans—are much more likely

to face the brunt of the shortage of affordable

and available housing. Past injustices, and the

absence of sufcient political responses to

remedy them, shape the opportunities people

have today. The intergenerational impacts

of slavery, segregation, discrimination, and

economic exploitation help to explain today’s

severe racial wealth inequality (Jones, 2017).

The disadvantaged circumstances that

children inherit become harder to overcome

as intergenerational economic mobility

declines (Chetty et al., 2017). When extremely

low-income renters

struggle to secure

affordable housing, it is

much more likely due

to systemic obstacles

than personal failings.

Because the affordable

housing shortage has been created and

perpetuated by our social, political, and

economic system, allowing it to persist is an

injustice. A just society is one in which the

ground rules are fair and justiable to all. We

cannot justify a system that persistently creates

deprivation when alternatives exist. Investing

in proven affordable housing solutions for

those most in need, then, is not only prudent

or generous – we have a shared moral

responsibility to rectify systemic injustices

(Young, 2011). Housing justice requires that,

at a minimum, no one is denied the ability

to meet their own basic needs because of

the systematic failures of our political and

economic system.

We cannot justify a

system that persistently

creates deprivation when

alternatives exist.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

21

CONCLUSION

e shortage of seven million rental homes

aordable and available to extremely low-income

households is a nationwide problem. e shortage

inicts substantial harms on the lowest-income

households, especially people of color: people who

lack the foundation of a stable, secure home suer

from worse health, poorer educational advancement,

and less economic mobility. e shortage at the

lowest end of the market leads to cumulative

shortages of aordable and available rental housing

for higher-income households as well. e private

market cannot and will not, on its own, build and

operate homes extremely low-income families can

aord. We need a sustained public commitment to

ensure the lowest-income households in America

have decent, stable, accessible, and aordable homes.

ABOUT THE DATA

is report is based on data from the 2018

American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use

Microdata Sample (PUMS). e ACS is an annual

nationwide survey of approximately 3.5 million

addresses. It provides timely data on the social,

economic, demographic, and housing characteristics

of the U.S. population. PUMS contains individual

ACS questionnaire records for a subsample of

housing units and their occupants.

PUMS data are available for geographic areas

called Public Use Microdata Sample Areas

(PUMAs). Individual PUMS records were matched

to their appropriate metropolitan area or given

nonmetropolitan status using the Missouri Census

Data Center’s MABLE/Geocorr 2014 Geographic

Correspondence Engine. If at least 50% of a PUMA

was in a Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA), we

assigned it to the CBSA. Otherwise, the PUMA

was given nonmetropolitan status.

Households were categorized by their incomes

(as extremely low-income, very low-income, low-

income, middle-income, or above median income)

relative to their metropolitan area’s median family

income or state’s nonmetropolitan median family

income, adjusted for household size. Housing units

were categorized according to the income needed to

aord the rent and utilities without spending more

than 30% of income. e categorization of units was

done without regard to the incomes of the current

tenants. Housing units without complete kitchen or

plumbing facilities were not included in the housing

supply.

After households and units were categorized,

we analyzed the extent to which households in

each income category resided in housing units

categorized as aordable for that income level.

For example, we estimated the number of units

aordable for extremely low-income households that

were occupied by extremely low-income households

and by other income groups.

We categorized households into mutually exclusive

household types in the following order: (1)

householder or householder’s spouse were at least

62 years of age (seniors); (2) householder and

householder’s spouse (if applicable) were younger

than 62 and at least one of them had a disability

(disabled); (3) non-senior non-disabled household.

We also categorized households into more detailed

mutually exclusive categories in the following

order: (1) elderly; (2) disabled; (3) householder and

householder’s spouse (if applicable) were younger

than 62 and unemployed; (4) householder and

householder’s spouse (if applicable) were enrolled in

school; (5) non-senior non-disabled single adult was

living with a young child under seven years of age or

person with disability.

More information about the ACS PUMS les is

available at https://www.census.gov/programs-

surveys/acs/technical-documentation/pums/about.

html

FOR MORE INFORMATION

For further information regarding this report and

the methodology, please contact Andrew Aurand,

NLIHC Vice President for Research, at

[email protected] or 202-662-1530 x245.

22

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2020

REFERENCES

Axel-Lute, M. (2017). Regulation and housing

supply: Where the left & right agree (sort of ).

Shelterforce, 186.

Bailey, P. (2020). Housing and health partners can

work together to close the housing aordability gap.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Bills, K. L., West, S. M., & Hargrove, J. (2019).

Housing cost burden and maternal stress among

very low income mothers. Journal of Sociology and

Social Welfare, 46(1), 73-89.

Bratt, R. G., Stone, M. E., & Hartman, C. (2006).

A Right to Housing: Foundation for a New Social Agenda.

Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Brennan, M., Reed, P., Sturtevant, L. (2014). e