Safeguarding America’s

Lands and Waters from

Invasive Species

A National Framework for Early Detection

and Rapid Response

Invasive Species on Cover:

Nutria, Myocastor coypus

(photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Green Crab, Carcinus maenas

(photo credit U.S. Geological Survey)

Burmese Python,

Python bivittatus

(photo credit U.S. Geological Survey)

Silver Carp,

Hypophthalmichthys molitrix

(photo credit Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee)

Red Lionfish,

Pterois volitans

(photo credit REEF)

W

ater Hyacinth, Eichhornia crassipes

(photo credit Bureau of Reclamation)

Asian Longhorned Beetle,

Anoplophora glabripennis

(photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Cheatgrass,

Bromus tectorum

(photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Zebra Mussel,

Dreissena polymorpha

(photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The following Federal agencies prepared this report:

Suggested citation:

The U.S. Department of the Interior. 2016. Safeguarding America’s lands and

waters from invasive species: A national framework for early detection and

rapid response, Washington D.C., 55p.

Co-Leads:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of the Secretary: Hilary A. Smith

National Invasive Species Council staff: Stanley W. Burgiel, Christopher P. Dionigi, and Jamie K. Reaser

In addition, this report has been prepared with the active consultation and assistance of

the National Invasive Species Advisory Committee's Early Detection and Rapid Response

subcommittee, including states, tribes, academic institutions, environmental

organizations, industry, and other organizations.

iii

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

CONTENTS

Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................v

Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................1

I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................5

The Charge ...............................................................................................................................................5

Invasive Species Management and Resilience .......................................................................................5

The Need for Early Detection and Rapid Response (EDRR) ..................................................................8

The Process for Preparing this Report .................................................................................................... 9

II. A National Early Detection and Rapid Response Framework ............................................................ 11

Purpose ................................................................................................................................................... 11

Guiding Principles ..................................................................................................................................12

Early Detection and Rapid Response ....................................................................................................13

Coordination, Roles, and Responsibilities ............................................................................................ 14

Organizational Structure .......................................................................................................................18

III. The EDRR Costs of Combatting Invasive Species ...............................................................................21

IV. Options for Funding the EDRR Framework ........................................................................................25

Scope of Activities .................................................................................................................................26

V. Recommendations ...............................................................................................................................29

VI. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................ 33

Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................34

Glossary .....................................................................................................................................................35

References .................................................................................................................................................37

APPENDIX A: EDRR Decision Making Process Template .........................................................................40

APPENDIX B: General EDRR Stages and Action Steps.............................................................................41

APPENDIX C: Examples of Current Invasive Species Networks ..............................................................49

APPENDIX D: Examples of Financing Models .......................................................................................... 53

APPENDIX E: Contributors ........................................................................................................................54

This page is intentionally left blank

v

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

FOREWORD

Invasive species pose one of the greatest ecological

threats to America’s lands and waters. Their control

can be complex and expensive and is often con-

ducted in perpetuity; their harm can be irreversible.

Early detection and rapid response (EDRR) actions

can reduce the long-term costs and economic bur-

den that invasive species have on communities.

Some invasive species, such as the pathogens that

cause chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease, staked

their claim in the United States in the early 1900s. As

a result, American chestnut and American elm trees

were

nearly eliminated from the Nation’s forests,

leaving in their wake devastating economic, social,

and ecological impacts. Invasive annual grasses, such

as cheatgrass, are rapidly replacing native plant spe-

cies across enormous areas of western rangelands.

Consequently

, wildfire frequency and intensity are

increasing while the ability of the vulnerable land-

scapes to support native wildlife, livestock opera-

tions, and agriculture are on the decline. A wide va-

riety of additional species are poised to arrive at U.S.

borders, many of them with the potential to cause

adverse impacts. For example, a deadly salaman-

der pathogen commonly known as ‘Bsal’ (short for

Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans) could cause

massive die-offs of salamanders across a wide range

of species and have cascading impacts on forest and

freshwater ecosystems.

These are just a few examples of a vast number of

invasive species that threaten the country’s wild-

lands, waterways, and coastlines. Their management

plays a fundamental role in the success of achieving

the Administration’

s conservation priorities, such as

enhancing climate resilience, promoting pollinator

health, and restoring landscapes.

The invasive species challenge can seem overwhelm-

ing, but strategic solutions can forestall future

invasive species impacts. This

report, Safeguarding

America’s lands and waters from invasive species: A

national framework for early detection and rapid re-

sponse, outlines opportunities to detect populations

of non-native species that pose the greatest risks to

landscapes and aquatic areas before they can have

adverse impacts, and swiftly respond to eradicate

them.

A shared commitment to problem solving

among Federal agencies, states, and tribes will lay

the foundation for more effective and cost-efficient

strategies to stop the spread of invasive species. This

national EDRR Framework proposes to connect ef-

forts among a diverse array of stakeholders at multi-

ple scales. It emphasizes a shared, renewed focus on

coordination and partnerships, science and technol-

ogy, and strategic on-the-ground action to reduce

the threat of invasive species and help protect the

Nation’s lands and waters, as well as the livelihoods

that rely upon them.

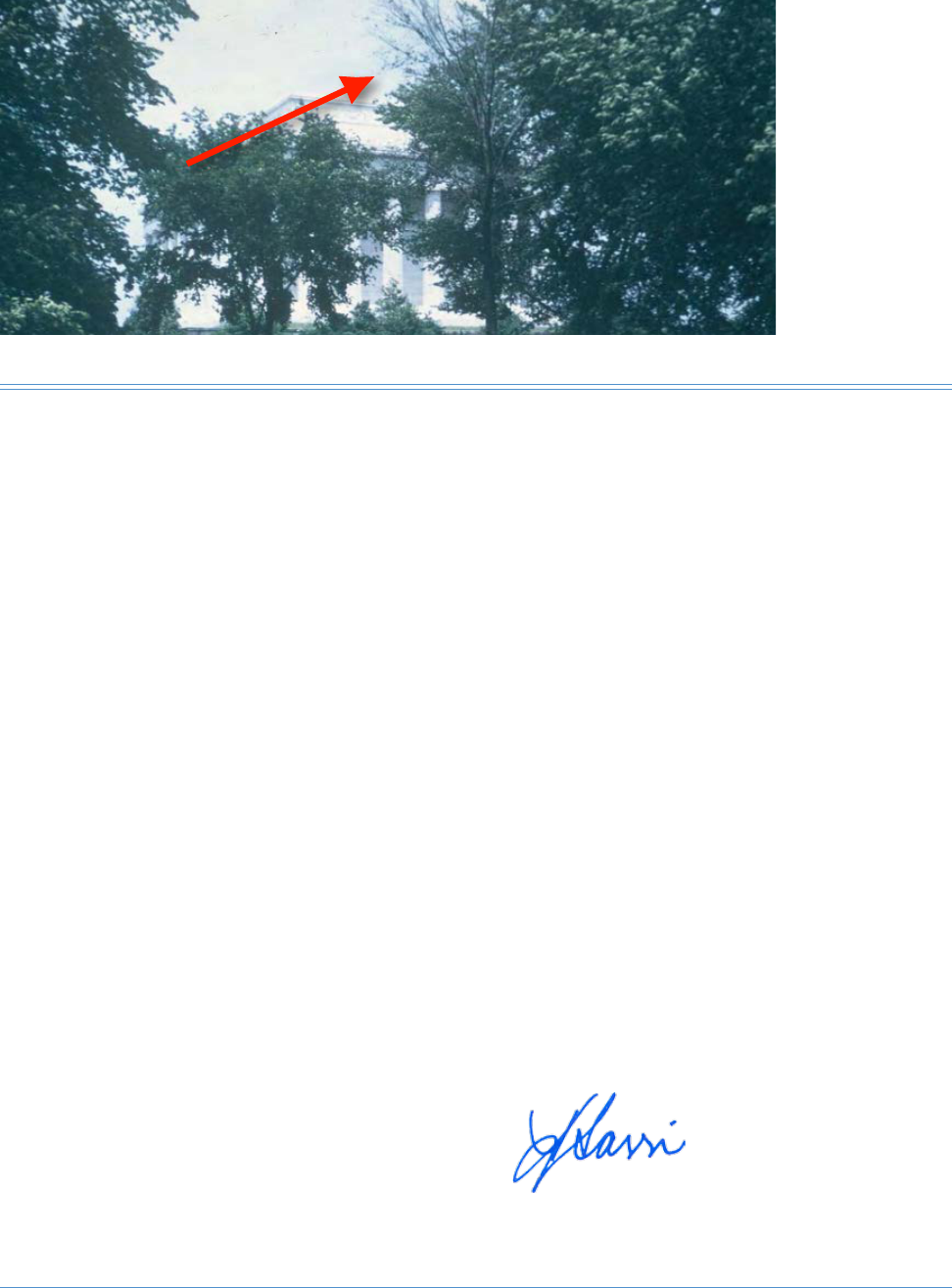

First elm found to

be infected with

Dutch elm disease

in Washington, D.C.;

Lincoln Memorial,

1947

(photo credit NPS)

Kristen J. Sarri

Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary

for Policy, Management and Budget

U

.S. Department of the Interior

This page is intentionally left blank

1

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Invasive species pose one of the greatest threats

to the Nation’s natural resources. The stakes are

high: if left to spread, invasive species cost billions

of dollars to manage and can have devastating

consequences on the Nation’s ecosystems (Pimentel

2003, Pimentel et al. 2005, Aukema et al. 2011). For

example, rapidly increasing lionfish populations

have drastically reduced the abundance of coral reef

fishes and degraded already stressed coral reefs.

Highly flammable cheatgrass and other invasive

grasses fuel more intense wildfires that put people

and livestock in harm’s way, degrade rangeland,

and damage critical habitat for wildlife, such as the

greater sage-grouse. Asian carp seriously impact

native fish populations and are poised to degrade

economically-important sport and commercial

fisheries. These and other invasive species transform

the Nation’s lands and waters, leaving extensive

economic and environmental costs in their wake.

While the invasive species challenge is daunting,

opportunities exist to turn the tide. Preventing the

introduction of invasive species is the first line of

defense against biological invasion. However, for

invasive species that circumvent prevention systems,

early detection and rapid response (EDRR)—a

coordinated set of actions to find and eradicate

potential invasive species before they spread

and cause harm—can help stop the next lionfish,

cheatgrass, or Asian carp.

More can be done to strengthen the Nation’s EDRR

capacity to get ahead of the next invasive species.

While there are well-established EDRR programs

to protect agricultural resources, there is a need

to extend efforts for EDRR programs that protect

non-agricultural areas, such as rivers and streams,

coastal waters, forests, and grasslands. Where they

exist, EDRR networks often focus only on select

species or geographic areas and are not always well-

coordinated with neighboring efforts. In addition,

EDRR networks frequently lack access to financial

resources, decision making tools, and other EDRR

capabilities necessary to find, contain, and eradicate

potentially invasive species populations before they

become widely established. These gaps result in

costly and often irreversible harm.

The site-based nature of EDRR actions also requires

partnerships and coordination across multiple scales

– however, there is no national EDRR framework

nor is there a coordinated strategy for funding

EDRR actions. Given the breadth of their missions,

authorities, technical capability, and funding,

Federal agencies are essential to addressing high-

risk invasive species and can provide crucial national

leadership and coordination. The continuous arrival

of potentially invasive species—and the expanding

ranges of current high-risk invasive species—

necessitates a national EDRR framework. A national

EDRR framework would build capacity to forecast

which species pose the greatest risks to the country,

bolster monitoring and response actions underway

across the country, and position public and private

partners to be prepared when the next invasive

species arrives. Because EDRR is always site-based

and specific localities are often resource limited, it is

imperative that such a framework have a structure

that functions effectively from the top down and

the bottom up in a fluid, reciprocal, and mutually

beneficial manner.

Silver Carp

Hypophthalmichthys

molitrix

(photo credit

Asian Carp Regional

Coordinating

Committee)

2

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

In October, 2014, the White House Council on Cli-

mate Preparedness and Resilience released its Pri-

ority Agenda: Enhancing the Climate Resilience

of America’s Natural Resources

, which identified

invasive species as one of the most pervasive threats

to ecosystem resilience in a changing climate and

called upon the U.S. Department of the Interior

(DOI), working with other members of the National

Invasive Species Council (NISC), states, and tribes, to

develop a framework for a national EDRR program,

including a plan for emergency response funding.

As called for in the Priority Agenda, this report pro-

poses a national EDRR framework (EDRR Frame-

work) that provides an organizational structure for

national coordination and communication among

Federal

and non-Federal entities to increase the

overall effectiveness of EDRR efforts, and thus pro-

tect ‘priority landscapes and aquatic areas’ from the

impacts of invasive species. In the context of the

EDRR Framework, priority landscapes and aquatic

areas are generally regarded as those lands and wa-

ters (freshwater, coastal, and marine) identified by

Federal, state, or tribal entities as areas of impor-

tance, such as for natural resource stewardship, con-

servation, or biodiversity purposes.

The EDRR Framework will:

1. Connect and build upon existing initiatives.

2. Identify gaps in EDRR coverage (e.g., taxo-

nomic groups, monitoring programs, and

localities)

and needs (e.g., tools, techniques,

skills, and human and financial resources).

3. Augment Federal, state, and tribal EDRR

capabilities, capacities, and partnerships.

4.

Establish a coordinated funding process

and/or mechanism(s) to support prepared-

ness and response activities.

RECOMMENDA

TIONS:

The Secretaries of the Departments of the Interior,

Agriculture, and Commerce, as co-chairs of NISC,

working with other members of NISC, should take

the following five steps to implement a national

EDRR Framework:

1. Establish a National EDRR Task Force and

designate a National EDRR Coordinator

within the NISC structure to address invasive

species that affect priority landscapes and

aquatic areas. An important step in imple-

menting the EDRR Framework is to estab-

lish a combined Federal/non-Federal Task

Force within the NISC structure that would

improve coordination among agencies, help

set shared priorities, and assess and close

important gaps in EDRR actions. A desig-

nated National EDRR Coordinator is essen-

tial to provide coordination across Federal

agencies and serve as the liaison with state,

tribal, regional, and other partners and ex-

perts to facilitate communications and iden-

tify efficient means to share information,

technologies, and other resources.

2.

Convene high-level decision makers (i.e.,

Assistant/Under Secretaries) and senior

budget officials within NISC agencies to bet-

ter align funding or guide the formation of

mor

e effective funding mechanisms to sup-

port preparedness and emergency response

activities. A range of financial, operational,

and human resources are necessary to im-

plement EDRR actions. An initial step in ad-

dressing funding challenges is to evaluate

current agency EDRR capacities, capabilities,

flexibilities, limitations, and magnitude of

needs. This includes an assessment of how

current EDRR efforts are supported through

various agency programs. Guidance from

decision makers and budget officials will be

essential to developing a plan to establish a

coordinated funding process or mechanism

that can effectively address EDRR needs and

help build capacity to mobilize resources to

partners on the ground.

3

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

3. Incorporate EDRR actions into NISC agency

programs and partnerships at national, re-

gional, and local scales. Establishing lead

contacts in Federal agencies working on

EDRR is an important step in implementing

the EDRR Framework and increasing com-

munications and collaboration across the

range of Federal, state, tribal, and local ju-

risdictions. Understanding Federal agency

authority to implement EDRR is another

critical step. Given differences across au-

thorizing legislation, the NISC should work

with member Federal agencies to assess

their capacity and capability under existing

authorities to implement EDRR. This assess-

ment should be conducted through a cen-

tralized process that is coordinated among

the Federal agencies and identify gaps, in-

consistencies, and conflicts in authorities

and policies as well as enforcement capac-

ity. Building on this review, the NISC should

work with member Federal agencies to de-

velop and implement a strategy requesting

supplemental authorities, if needed, to fully

implement the EDRR Framework. This strat-

egy should consider the role of EDRR within

the broader context of invasive species pre-

vention and management activities. Federal

agencies should also identify crosscutting

initiatives, such as climate preparedness

plans, where EDRR applies and incorporate

appropriate EDRR actions.

4. Advance multiple pilot EDRR initiatives in

priority landscapes and aquatic areas. Cur-

rent EDRR capacities vary across the country.

Implementation of the EDRR Framework

likely will occur in a staged approach. As an

initial step, agencies should identify several

priority landscapes and aquatic areas to pi-

lot elements of the EDRR Framework. Such

ef

forts would be instrumental in the iden-

tification and application of performance

measures and other metrics for the effec-

tiveness and value-added contribution of

EDRR activities.

5. Foster the development and application of

EDRR capabilities, including technologies,

analytical and decision making tools, and

best practices. A range of capabilities (e.g.,

risk assessments, monitoring programs,

identification support, alert systems, eradi-

cation techniques etc.) is necessary to sup-

port effective EDRR. EDRR capabilities will

help

determine priority invasive species and

actions for national EDRR efforts as well as

priority pathways to be addressed and ar-

eas most vulnerable to invasion. Analytics

and decision tools will help determine what

rapid response measures should be taken

and when. While some of these tools cur-

rently exist, a coordinated effort is needed

to assess, prioritize, enhance, develop, dis-

seminate, and apply them in the field. This

includes the research to support these EDRR

capabilities.

It is imperative to stop the next invasive species

from staking a claim in the Nation’s lands and wa-

ters. Taken together, these steps will operationalize

a national EDRR Framework that supports the de-

tection, identification, and eradication of invasive

species populations before they spread and cause

significant harm. The EDRR Framework provides the

structure to identify strategic and shared priorities

for focusing limited resources and enhancing part-

nerships and on-the-ground actions necessary to

stem the tide of invasive species.

4

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

Invasive Species

An invasive species is an alien species whose introduction does or is

likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human

health (Executive Order 13112). An alien species is, with respect to a

particular ecosystem, any species, including its seeds, eggs, spores, or

other biological material capable of propagating that species, that is

not native to that ecosystem (Executive Order 13112). For the purposes

of this report, the terms ‘alien’ and ‘non-native’ are regarded as

synonymous.

Biological Invasion, Early Detection & Rapid Response

Biological invasion is the process by which non-native species breach

biogeographic barriers and extend their range (McGraw-Hill 2003).

In the context of biological invasion, early detection is the process of

surveying for, reporting, and verifying the presence of a non-native

species, before the founding population becomes established or

spreads so widely that eradication is no longer feasible. Rapid response

is the process that is employed to eradicate the founding population of

a non-native species from a specific location.

Purple Loosestrife

Lythrum salicaria

(photo credit NPS)

5

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

The Charge

In October 2014, the White House Council on Cli-

mate Preparedness and Resilience released Prior-

ity Agenda: Enhancing the Climate Resilience of

America’s Natural Resources.

One of the Priority

Agenda’s four strategies is to foster climate-resilient

lands and waters, calling upon Federal agencies to

“Identify Landscape Conservation Priorities to Build

Resilience.”

More specifically, the Council on Climate Prepared-

ness and Resilience delivered the following charge

to DOI and NISC

1

:

“The Secretary of the Interior, working with

other members of the National Invasive Species

Council, including Department of Commerce

(National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminis-

tration [NOAA]), the Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA), and the U.S. Department of Agri-

culture (USDA), will work with states and tribes

to develop a framework for a national Early

Detection and Rapid Response (EDRR) program

that will build on existing programs to assist

states and tribes in forestalling the stress caused

by the establishment and spread of additional

invasive species populations, thereby improv-

ing the resilience of priority landscapes and

aquatic areas. This will include the development

of a plan for creating an emergency response

fund to increase the capacity of interagency

and inter-jurisdictional teams to tackle emerg-

ing invasive species issues across landscapes and

jurisdictions.” (Council on Climate Preparedness

and Resilience 2014)

This charge furthers priorities set forth in Executive

Order 13112 (Invasive Species) and advances work

directed by the National Invasive Species Manage-

ment Plans.

Invasive Species Management

and

Resilience

Invasive species are one of the most significant driv-

ers of environmental degradation and species ex-

tinction worldwide and are generally considered

the primary cause of biodiversity loss in freshwater

and island ecosystems. Invasive species are respon-

sible for the endangerment and extinction of a wide

range of taxa; degradation of freshwater, marine,

terrestrial ecosystems; and, the alteration of biogeo-

chemical cycles. They contribute to social instability

and economic hardship, consequently placing con-

straints on the conservation of biodiversity, sustain-

able development, and economic growth. The glo-

balization of trade, travel, and transport is greatly

increasing the number and type of non-native spe-

cies that are being moved around the world, as well

as the rate at which they are moving. At the same

time, changes in climate and land use are rendering

some habitats, even the best protected and most re-

mote natural areas, more susceptible to biological

invasion (McNeely 2001; Reaser et al. 2004).

I. INTRODUCTION

1 Established by Executive Order 13112, the NISC membership includes 13 Federal Departments and Agencies. It is co-chaired by the

Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Agriculture, and the Secretary of Commerce. The NISC provides national coordination on the

broad array of activities intended to protect the environment, economy, and human and animal health from the adverse impacts of

invasive species.

Kudzu

Pueraria lobata

(photo credit NPS)

6

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

Priority Landscapes and Aquatic Areas

In the context of this proposed national EDRR Framework, ‘priority

landscapes and aquatic areas’ are generally regarded as those lands

and waters (freshwater, coastal, and marine) identified by Federal, state,

or tribal entities as areas of importance, such as for natural resource

stewardship, conservation, or biodiversity purposes.

The Need for a National EDRR Framework

Federal and non-Federal partners have long recognized the need for

a national Early Detection and Rapid Response (EDRR) framework to

protect landscapes and aquatic areas from the impacts of invasive

species. Some of the more recent documents recommending the

formation of an EDRR framework include the National Invasive Species

Council’s Management Plans, the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force’s

Strategic Plans, the National Ocean Policy, the Implementation Plan for

the National Strategy for the Arctic Region, the Recommendations to

the President from the State, Local and Tribal Leaders Task Force on

Climate Preparedness and Resilience, and most recently in the Western

Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Invasive Plant Management

and Greater Sage-Grouse Conservation Plan and the Rangeland Fire

Task Force’s Integrated Rangeland Fire Management Strategy.

7

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

The Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force (ANSTF)/

NISC Ad Hoc Working Group on Invasive Species and

Climate Change (2014) identified numerous ways

in which the interactions between invasive species

and climate change can exacerbate the risks and

impacts associated with both ecological threats. For

example, changing climate conditions may contrib-

ute to the increase of invasive species through faster

species growth rates (e.g., changing levels of CO

2

and precipitation may favor some invasive species),

species range shifts (e.g., increases in temperature

may enable some invasive species to survive in eco-

systems where cold temperatures were previously

lethal), and new pathways of species spread (e.g.,

travel, trade, and extreme weather events may in-

fluence invasive species dispersal). Likewise, the

impacts of invasive species can substantially hinder

ecosystem resilience to other stressors, especially cli-

mate change (Burgiel and Muir 2010, U.S. Environ-

mental Protection Agency 2008).

It, therefore, follows that ecological resilience to

climate change can be improved by preventing

the adverse impacts of invasive species. Prevention

(border control and pathway management

2

) is gen-

erally regarded as the first line of defense against

biological invasion. Yet, despite the best available

prevention efforts, in time, some non-native species

will be introduced and/or spread into new ecosys-

tems. EDRR then becomes the most cost-effective re-

sponse strategy; eradication of the founding popu-

lation of the non-native species alleviates the need

for expensive invasive species control programs that

would have to be enacted over the long-term. [See

Diagram: The Invasion Curve (Fig. 1).] Effective EDRR

can also be viewed as a conflict mitigation strategy

since it prevents the conflicts that invariably arise

over land use and land management approaches

once invasive species become well established.

While recognizing that investments in border control

and pathway management are the logical priority to

prevent the introduction and spread of invasive spe-

cies,

3

this report focuses on the eradication of those

non-native species which circumvent prevention

systems. In particular, it responds to the Council on

Climate Preparedness and Resilience’s charge to de-

velop a framework for a national EDRR program

that ultimately improves the resilience of priority

landscapes and aquatic areas through the eradica-

tion of emerging invasive species.

When introduced outside their

native ranges, nutria (

Myocastor

coypus

) and beach vitex (

Vitex

rotundifolia

) are known to degrade

wetland and coastal dune systems,

respectively, making impacted

areas more vulnerable to erosion

and storm surges. Detecting and

eliminating incipient populations

of these species in new areas

can forestall the immediate

degradation of these ecosystems,

and help maintain the ability of

these ecosystems to serve as

buffers from severe weather events

(Westbrooks and Madsen 2006,

Carter et al. 1999).

2 Pathways are the means by which invasive species are moved, intentionally or unintentionally, into new areas. Pathways can broadly be

categorized in relation to trade and the movement of goods (e.g., horticultural products, firewood, pets, wooden packaging materials);

transportation (e.g., ballast water and hull fouling of commercial and recreational vessels; construction and off-road vehicles); and,

infrastructure and resource management (e.g., energy development and construction equipment and habitat restoration practices).

3 Federal activities related to preventing the introduction and spread of invasive species include work at national borders and within the

United States using both regulatory and non-regulatory approaches to address the pathways of invasion. These activities represent the

most significant share of spending by Federal agencies (see page 21).

8

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

The Need for Early Detection and

Rapid Response (EDRR)

The continuing arrival of potentially invasive spe-

cies and range expansions of existing invasive spe-

cies necessitates coordinated EDRR actions. In recent

years, several invasive species introductions were

detected early, but without a nationally coordinat-

ed response effort, those populations continued to

spread to an extent where eradication is no longer

feasible. Examples include redbay ambrosia beetles

(Xyleborus glabratus), which carry the laurel wilt

fungus (first detected in Georgia in 2002); lionfish

(Pterois volitans), a major predator in coastal sys-

tems that damages coral reef habitats (first detected

off of Florida in 1985); and, the raspberry crazy ant

(Nylanderia fulva), a major insect pest with impacts

on wildlife, livestock, and electrical equipment and

other infrastructure (first detected in Texas in 2002).

In these cases, the lead agency, the authorities to re-

spond, and/or the potential risks and impacts were

not clear when these invasive species were first de-

tected. In other cases, the lead agency—when faced

with limited funding—was not able to respond.

EDRR can work, and, there are examples of suc-

cess from across the country. A number of effective

EDRR

efforts brought together the necessary play-

ers, management techniques, and resources, such as

eradication of Caulerpa taxifolia, an invasive alga,

in southern California (2006); removal of the sacred

ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) in Miami-Dade and

Palm Beach counties, Florida (2008-2011); detection

and removal of floating docks infested with poten-

tial aquatic invasive species (AIS) that were washed

Entry of Invasive Species

THE INVASION CURVE

Long-Term Control

Containment

Eradication

EDRR

Window of Opportunity

Prevention

Invasive

species

absent

Small number of

localized populations;

eradication possible

Rapid increase in

distribution and abundance;

eradication unlikely

Invasive species widespread and abundant;

long-term control aimed at population supression and

resource protection

Figure 1: Phases of the Invasion Curve (Rodgers, Adapted from Invasive Plants and Animals Policy

Framework, State of Victoria, Department of Primary Industries, 2010, modified with permission).

Preventing the introduction (e.g., border controls, pathway management) of invasive species is the

first line and most cost-effective defense against biological invasion. The second line of defense is

eradication, where the approach is to eliminate founding populations of invasive species while doing

so is feasible. EDRR is generally necessary to achieve eradication. When eradication is no longer

feasible, then containment or long-term control of an invasive species population is the last remaining

management option. Long-term control programs require substantial financial investments in

perpetuity.

9

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

ashore in Oregon and Washington in the wake of a

Japanese tsunami (2013); and, ongoing monitoring

and response efforts to keep the Great Lakes free of

Asian carp. These efforts helped to protect native

fish and wildlife populations and investments made

by other conservation and restoration programs in

these areas and prevented future costs and dam-

ages from these invasive species.

The elements of this national EDRR framework

take into account past successes with EDRR, as well

as current initiatives, particularly in areas where

states, tribes, Federal agencies, and other partners

are jointly investing in EDRR activities. For exam-

ple, Western states are increasingly collaborating

around watercraft inspection and decontamination

ef

forts to keep quagga and zebra mussels out of

Western waterbodies. Similarly, a range of experts

from academia and state and Federal agencies are

developing surveillance and response protocols for

a deadly fungus of salamanders—Batrachochytrium

salamandrivorans or Bsal

—that has yet to be detect-

ed in the United States. These are but two examples

of a range of initiatives targeting some of the many

terrestrial and aquatic invasive species that threaten

the Nation’s natural resources. The Federal Govern-

ment’s leadership and targeted coordination and re-

sources through a national EDRR framework could

mean the difference between failure and success of

these types of EDRR activities.

The Federal Government has a natural role in help-

ing to address high-risk invasive species given the

breadth of Federal agency missions, authorities,

technical capability

, and funding. A structured, stra-

tegic, national approach for EDRR, coupled with

sufficient funding, are necessary to effectively stop

potentially invasive species before they can establish

and spread and cause widespread, costly damage.

The proposed national EDRR Framework would help

turn that tide by facilitating coordination on multi-

ple scales, designating responsible points of contact

within government agencies, identifying technical

expertise and tools, and providing financial assis-

tance.

The Process for Preparing this Report

To develop a national EDRR Framework (hereaf-

ter the EDRR Framework), DOI and NISC convened

a group of Federal experts to identify central ele-

ments, parameters, and critical stakeholders. They

formed a broader advisory team under the umbrella

of NISC’s Invasive Species Advisory Committee (ISAC)

to serve as a forum for engaging states, tribes, and

other parties interested in assessing the national

needs and strategic considerations for the design,

coordination, and implementation of a national

EDRR framework. The DOI and NISC also shared

progress and key concepts with various Federal

working groups during this report’s development

and held a tribal listening session and a tribal con-

sultation to solicit further input on tribal issues and

perspectives.

The following sections address the principles of an

EDRR Framework and the particular phases of the

EDRR process. The EDRR Framework is divided into

components focused on preparedness, early detec-

tion, rapid assessment, and rapid response. Coordi-

nation and the identification of responsible institu-

tions and partnerships are also critical elements for

the EDRR Framework’

s implementation.

Financial resources and flexible funding mechanisms

are fundamental needs to implement the EDRR

Framework successfully. Section IV (page 25) is dedi-

cated to this topic.

The recommendations provided on page 29 are in-

tended to serve as guidance in the establishment

and

initial implementation of the EDRR Framework,

and are explicitly directed at the Secretaries of the

Departments that co-chair NISC.

Supporting appendices include a template for an

EDRR decision making process, the stages of the

EDRR process and general action steps, examples

of current invasive species networks, examples of

financing models, and the members of the Federal

work group and its advisory team that assisted with

developing the EDRR Framework.

This page is intentionally left blank

11

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

Purpose

The EDRR Framework is a proposed organizational

structure that enables national coordination and

communication among Federal and non-Federal en-

tities to increase the overall effectiveness of EDRR

efforts to forestall the establishment and spread

of invasive species, and thus protect priority land-

scapes and aquatic areas, as well as the ecosystem

services they provide. In the context of the EDRR

Framework, priority landscapes and aquatic areas

are generally regarded as those lands and waters

(freshwater, coastal, and marine) identified by Fed-

eral, state, or tribal entities as areas of importance,

such as for natural resource stewardship, conserva-

tion, or biodiversity purposes. Identifying the crite-

ria and decision making processes to determine pri-

ority landscapes and aquatic areas where the EDRR

Framework would apply is outside of the scope of

this report. Those details are fundamental to the

implementation of the EDRR Framework and will

need to be developed, in cooperation with states

and tribal partners. Implementation will occur in a

phased approach and be informed by science-based

assessments.

Implementing the EDRR Framework will:

1. Connect and build upon existing initiatives.

2. Identify gaps in EDRR coverage (e.g., taxo

-

nomic groups, monitoring programs, and

localities)

and needs (e.g., tools, techniques,

skills, and human and financial resources).

3. Augment Federal, state, and tribal EDRR ca-

pabilities, capacities, and partnerships.

4.

Establish a coordinated funding process

and/or mechanism(s) to support prepared-

ness and response activities.

II. A NATIONAL EARLY DETECTION AND RAPID RESPONSE FRAMEWORK

The national EDRR Framework focuses on invasive species—plants, animals, and other

organisms—that may adversely impact (harm) priority landscapes and aquatic areas in

the United States. The work done under the EDRR Framework will not be redundant

or overlap with the work of agencies with specific statutory charges to address invasive

species, such as USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). Rather

the work will focus on coordinating EDRR in areas where gaps in EDRR leadership

and resources exist and working toward a goal of being complementary and mutually

supportive but not duplicative.

Burmese Python

Python bivittatus

(photo credit USGS)

12

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

Under the EDRR Framework, actions may be taken

to eradicate populations of potentially invasive spe-

cies that are new to the United States or contain

the spread of known invasive species by eradicating

satellite populations that could result in range ex-

pansions. Appendix A provides a template for a gen-

eral decision making process for EDRR events (i.e.,

when a detection occurs) and describes the general

flow of information and decision points in the EDRR

process.

The national scope of the EDRR Framework neces-

sitates the involvement, coordination, and coop-

eration of Federal agencies, particularly those with

natural resource management and regulatory re-

sponsibilities, scientific expertise, information man-

agement capabilities, and emergency response ca-

pacity. Leveraging the vision and resources for an

EDRR

Framework at the national level will enhance

regional, state, tribal, and local EDRR efforts by

providing additional leadership, guidance, and ac-

cess to human, technical, and financial resources.

Because EDRR is always site-based and specific lo-

calities are typically resource limited, it is imperative

that a national EDRR Framework have a structure

that functions effectively from the top down and

the bottom up in a fluid, reciprocal, and mutually

beneficial manner.

Guiding Principles

Complementarity: The EDRR Framework draws from

existing programs; numerous models, plans, and

protocols informed its structure. It seeks to enhance

and not duplicate existing efforts. It achieves

this by having involved a broad range of Federal

and non-Federal partners in its development and

building their involvement into its structure and

implementation.

Partnership: The involvement of and support for

states, tribes, non-governmental organizations,

industry, and others working to address invasive

species is a key aspect of the EDRR Framework’s

cooperative intent. Given the myriad of players and

different jurisdictions associated with connecting

lands and waters, as well as the numerous authorities

related to their management, the development

of effective partnerships is critical to mitigating

the potential impacts of invasive species at the

landscape scale. The EDRR Framework can facilitate

cooperation and communication across regulatory

agencies as appropriate.

Scale: Some of the components of the EDRR

Framework are scale independent and can be

models for the national, regional, state, tribal, or

local level. For example, the EDRR decision making

template (see Appendix A) and general EDRR stages

and action steps (see Appendix B) are applicable at

any scale.

Implementation: The intent of the EDRR Framework

is to guide the transition from existing conceptual

models, particularly at a national scale, to a

practical, operational structure through which

implementation can progress. The EDRR Framework

necessarily addresses the funding, identification of

the responsible institutions and other participants,

authorities, and skills and capacities necessary for

effective EDRR.

Timeliness: The EDRR Framework reflects the

importance of early detection and rapid response

to identify, assess, and respond quickly to the

introduction of a potentially invasive species.

The window of opportunity for a timely response

depends on the invasive species (e.g., under its

own power, an introduced invasive plant is likely

to spread slower than an introduced invasive fish).

The EDRR Framework emphasizes the need for a

streamlined and continuous process from detection

to eradication that prevents delays.

Resource availability: The availability of resources

(financial, technical, and human) and flexibility of

funding mechanisms determines the timeliness

and range of actions that can be successfully

implemented once a potentially invasive species is

detected. Targeted funding will be necessary to fully

implement EDRR for potentially invasive species and

should allow resources to be transferred among

partners without delay.

Metrics: The activities associated with the EDRR

Framework will require a set of performance measures

to evaluate their efficiency and effectiveness, as

well as to enable adaptive management. These will

be developed in the implementation phase of the

EDRR Framework. Analysis of metrics will enable

improvements to the design and implementation of

the EDRR Framework over time.

13

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

A national EDRR Framework needs to consider non-

native species that are new to the United States (i.e.,

first time introductions), as well as invasive species

that are already in the United States but have been

introduced to a new ecosystem or have spread be-

yond the area occupied by the founding population.

Detecting and responding to invasive species re-

quires a series of sustained and coordinated actions

with associated responsible agencies and partners.

The EDRR Framework identifies four general cate-

gories or stages of the EDRR process (see Fig. 2), and

each of these categories involves numerous action

steps (see Fig. 3 and Appendix B):

¡¡ Pr

eparedness: Establishes the plans, coordi-

nation networks, tools, training, and neces-

sary resources for deployment of detection,

r

apid assessment, and rapid response actions.

¡¡ Early detection: Through surveys and moni-

toring activities,

4

provides initial evidence on

the occurrence of a potentially invasive spe-

cies and the mechanisms for reporting and

ve

rifying species identification.

¡¡ Rapid assessment: Determines the distribu-

tion and abundance of the species occurrence,

if

possible, and evaluates its potential risks

with regard to environmental, health, and

economic impacts. It also identifies options

for rapid response based on the particular

circumstances associated with the occurrence

of the species (e.g., species type, specific loca

-

tion, extent of spread, relevant jurisdictions/

a

uthorities).

¡¡ Rapid response: A set of coordinated actions

to eradicate the founding population of an

invasive species before it establishes and/or

spreads to the extent that eradication is no

longer feasible.

Eradication of the targeted invasive species is the

primary goal of the EDRR process. Appendix A

provides a template for a general decision mak

-

ing process for responding to non-native species in

new

localities and describes the general flow of in-

formation and decision points in the EDRR process.

The following types of indicators help to evaluate

the

extent to which an EDRR response is successful

(NISC 2003):

1. Timeliness of the detection: Potential-

ly invasive species are detected upon

introduction.

2.

Availability and accessibility of resources:

Technical, financial, and human resources

are readily available to support assessment

and response efforts.

3. Timeliness of the response actions: Rapid

response to the introduction forestalls the

establishment, spread, and adverse impacts

of the invasive species.

4. Timeliness of information: Information is

provided to decision-makers, the public,

and to partners.

5. Adaptive management:

A systematic ap-

proach is used for improving resource man-

agement by learning from management

outcomes from EDRR.

5

Early DetectionEarly Detection

Rapid AssessmentRapid Assessment

Rapid ResponseRapid Response

PreparednessPreparedness

Figure 2: General stages of the EDRR Process.

Preparedness actions are necessary in

advance of early detection and throughout

each stage of the EDRR process.

4 In the context of this report, references to monitoring include one-time surveys (aka inventories), as well as monitoring activities

(i.e., surveys repeated over time).

5 See Glossary for a detailed definition of adaptive management.

Early Detection and Rapid Response

14

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

Coordination, Roles,

and

Responsibilities

Jurisdictional boundaries do not limit invasive spe-

cies infestations; thus, coordination among neigh-

boring jurisdictions is essential for EDRR to be

successful. Active partners in EDRR activities may in-

clude Federal, state, tribal, and local governments,

as well as regional authorities and a range of site-

based partners, including landowners, local natu-

ralists, and issue experts. The descriptions below

outline the general interests of the primary stake-

holders in the national EDRR Framework.

Federal Agencies: Federal agencies have a number

of key roles in EDRR including responsibilities for

managing Federal lands and waters, enforcing Fed-

eral laws, exercising regulatory authorities, and pro-

viding technical expertise in management, research,

and information systems.

The Federal government

manages approximately 635 million acres in the

United States, the majority of which are adminis-

tered by the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Park Service

(NPS), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), and Department

of Defense (CRS 2012). The NOAA is responsible for

marine sanctuaries. The U.S. Coast Guard enforces

laws protecting waters from non-native species. The

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) plays an important

role as trustee and advisor for tribally owned lands.

Some relevant Federal regulatory authorities in-

clude the ability to prohibit the import into the

United States and the interstate transport of listed

invasive injurious species, approve specific pesti-

cides and their applications, engage in emergency

response actions, and manage risks associated with

certain major pathways of invasive species introduc-

tion. Many Federal agencies are active in the devel-

opment and application of tools for invasive species

assessment, detection, reporting, species monitor-

ing and surveillance, management, and identifica-

tion. Such agencies are a key resource for the col-

lection of data regarding invasive species ecology,

impacts, and geographic distribution.

State Agencies:

In many ways, state agency activi-

ties mirror those at the Federal level but within the

bounds

of their state borders. States have a wide

range of authorities to manage invasive species and

often have a more direct line of communication to

the counties, municipalities, and private landown-

ers at the site level. States have a vested interest

in cooperating with neighboring states to address

common priorities, such as particular invasive spe-

cies of concern and ecosystems that extend across

jurisdictional borders. For example, Great Lakes

states are collaborating on ef

forts to prevent the

spread of Asian carp, and Western states are work-

ing together to conserve the sage-grouse and sage-

brush steppe ecosystem from invasive annual grass-

es, such as cheatgrass. In addition, many states have

established or are forming invasive species councils,

invasive plant councils, statewide networks of local

invasive species cooperatives

6

, and aquatic nuisance

species (ANS) management plans that provide an

important basis for coordinated planning and ac-

tion.

Tribes: There are 567 recognized American Indian

tribes. The BIA is responsible for the administration

of 55 million surface acres and 57 million acres of

subsurface mineral estates held in trust for Ameri-

can Indian tribes and Alaska Natives. Tribal govern-

ments govern approximately 275 land areas in the

United States designated as Indian Reservations.

Millions

of off-reservation acres, particularly in the

Pacific Northwest and Great Lakes regions, are also

under inter-tribal co-management with states for

conservation purposes and fish, wildlife, shellfish,

and plant gathering activities. Under the doctrine

of trust responsibility, the U.S. Federal government

views Federally recognized tribal nations as domes-

tic dependent nations that have an inherent author-

ity for self-governance.

Tribal nations have authority to lead EDRR activi-

ties on tribal lands and waters and have traditional

ecological knowledge of the natural resources and

cultural practices on these lands and waters, includ-

ing ceded lands. Tribal engagement in EDRR activi-

ties varies from extensive (e.g., having staff, plans,

funding, and working relationships with adjacent

landowners) to nonexistent due to limited to no

capacity or resources. In 2014, BIA initiated an an-

nual invasive species competitive funding program

for tribes that helps to support a range of activities,

such as invasive species planning, monitoring, map-

ping, control, and education and outreach.

Regional Bodies:

Governmental and non-govern-

mental entities play a critical role in identifying and

coordinating activities across states and geogra-

phies. Regional governors associations and interstate

cooperatives provide a mechanism for multi-state

collaboration on shared priorities. Federal agencies,

6 Local invasive species cooperatives include cooperative weed management areas (CWMAs), cooperative invasive species management

areas (CISMAs), and partnerships for regional invasive species management (PRISMs), among others.

15

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

such as the USFS, USFWS, and EPA, have networks

of regional offices to support work on Federal lands

and waters and with states at the site level. The

ANSTF Regional Panels are a valuable network that

serves at the interface of Federal and state activi-

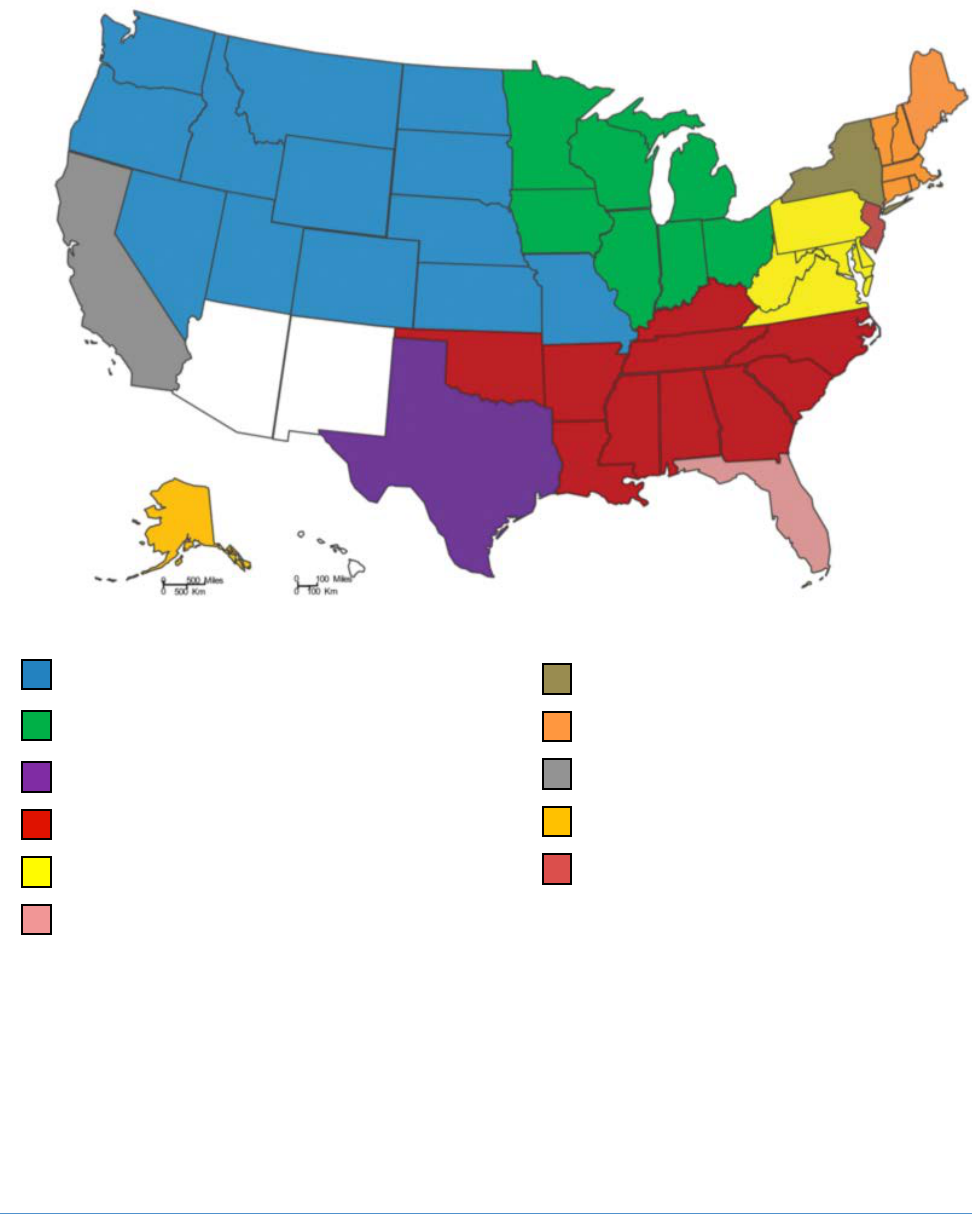

ties on ANS. [See Appendix C, Fig. C1, which shows

the coverage of ANS Regional Panels that focus on

a range of AIS strategies, including EDRR.] State and

regional invasive plant councils provide a similar

support function on terrestrial plant issues. [See Ap-

pendix C, Fig. C2, which shows the coverage of state

and regional invasive plant networks that address

invasive plant issues, including EDRR.]

A range of regional entities, such as the Landscape

Conservation Cooperatives, DOI’s Climate Science

Centers, and NOAA’s estuarine research reserves and

marine sanctuaries enhance research and manage-

ment issues relevant to the EDRR of invasive species.

While the focus of the EDRR Framework is domes-

tic, there may be cases where EDRR activities re-

quire collaboration with neighboring countries, and

thereby could involve relevant bi-national entities,

such as the U.S.-Mexico International Boundary and

W

ater Commission, the U.S.-Canada International

Joint Commission, and the Border Environment Co-

operation Commission.

Site-Based Partners and Other Technical Experts:

Counties, municipalities, water management and ir-

rigation districts, private citizens, corporations, land

trusts, and other non-governmental organizations

own and manage lands and waters. A range of en-

tities support EDRR activities, such as local invasive

species

cooperatives

7

, citizen science initiatives, mas-

ter naturalist groups and natural history clubs, and

stewardship programs. [See Appendix C, Fig. C3,

which illustrates a range of EDRR networks and Fig.

C4, which shows the coverage of hundreds of local

invasive species cooperatives that span the United

States.] They provide important mechanisms for lo-

cal coordination and often are the first to observe

and report new invasive species.

Academic, industry, and non-governmental orga-

nizations provide access to significant expertise on

species, pathways, and EDRR methods and tools.

For example, universities and

the private sector can

play a critical role in developing detection technolo-

gies and diagnostic methods for the identification

of potential invasive species. The private sector has

also played an important role in the development of

A wide range of EDRR efforts are

underway in the United States.

These initiatives vary across

species of concern, geographies,

legal jurisdictions, and agency

authorities. A unifying vision and

national framework will help

ensure effective coordination and

timely communication among

these efforts. The USDA Animal

and Plant Health Inspection Service

(APHIS) operates an EDRR program

on plant and animal health that

primarily focuses on agricultural

and livestock concerns. Additionally,

the Federal Interagency Committee

for the Management of Noxious

and Exotic Weeds (FICMNEW) and

the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) have

EDRR models for use in terrestrial

systems. Taxonomic and/or

geographic-specific efforts such as

the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task

Force’s (ANSTF) Aquatic Nuisance

Species (ANS) Regional Panels

may also support and engage in

EDRR activities. In addition, a wide

array of local EDRR initiatives is

underway through invasive species

cooperatives involving citizen

scientists; in some cases, these

local cooperatives form statewide

networks (e.g., in Florida, New

York, and Hawaii). A nationally

coordinated EDRR framework that

provides the rapid communication

and organizational development

mechanisms, EDRR tools that can be

readily accessed and shared, training

and other forms of capacity building,

and sufficient funding would greatly

enhance the effectiveness of all of

these initiatives, as well as fill the

gaps in EDRR coverage that currently

enable invasive species to diminish

the value of priority landscapes and

aquatic areas.

7 See footnote 6.

16

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

control techniques and products, as well as in moni-

toring activities that may relate to their corporate

activities or environmental footprint.

The national EDRR Framework will connect

and enhance existing efforts across all

stages of the EDRR process: preparedness,

early detection, rapid assessment, and rapid

response. For example, EDRR actions benefit

from a variety of detection networks. Many

monitoring programs exist, including paid

professionals and an increasing number of

volunteer citizen scientists and naturalists.

Monitoring efforts often focus on specific

species or groups of species (e.g., lionfish or

aquatic invasive species), high-risk pathways

(e.g., ports of entry and urban environments),

and/or protecting high-value locations (e.g.,

Great Lakes). There is a need to expand these

existing programs and to engage other types

of monitoring efforts to aid in invasive species

detection. Examples include ecological

monitoring programs, tree health monitoring

networks, and marine monitoring efforts,

among others. Enlisting the assistance of field

personnel, such as foresters, fire program

staff, and transportation staff also will help

broaden the reach of detection efforts.

Detections may also occur outside of formal

monitoring networks, such as by private

citizens, who have a strong knowledge

of local plants and wildlife. Federal, state,

local, tribal, and private sector entities are

all important partners in early detection.

Education and training programs to inform

personnel, practitioners, volunteers, and

the public about potentially invasive species

are critical to help increase the likelihood of

detecting new introductions.

Finally, non-governmental organizations play a

key role in the development, use, and application

of technologies, working across governmental and

non-governmental entities, and helping to identify

priority habitats and species.

Red Lionfish

Pterois volitans

17

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

The EDRR Framework builds upon and integrates

the services and capabilities that this range of

entities offers, while also helping to identify key

geographic, taxonomic, programmatic, and skill-

based gaps.

Some of initial gaps in EDRR capabilities and ca-

pacities that the EDRR Framework would aim to en-

hance include conducting national risk assessments

to

determine high-risk species that threaten prior-

ity landscapes and aquatic areas, priority pathways,

and priority areas vulnerable to invasion; prioritiz-

ing species to help focus monitoring and research

critical to improving detection and eradication tech-

nologies and methods; strengthening monitoring

programs and taxonomic capacity/tools for rapid

specimen identification; supporting information sys-

tems to inform decision making; and, developing a

well-coordinated national alert system.

Federal agencies play a critical role in addressing

some of these gaps, such as conducting horizon

scanning

8

and risk analysis to determine the invasive

species that pose the highest risk to the Nation;

developing and providing access to EDRR tools; or,

helping to support emergency responses for priority

invasive species

9

. For others, non-Federal partners

may play a critical role, such as coordinating

citizen science monitoring programs, defining site-

specific reporting protocols, and engaging private

landowners. It is important to note that the roles

and responsibilities across the range of EDRR action

steps (see Fig. 3) are fluid. For example, lead agencies

will vary among EDRR events based on the species,

the location of the population, the authorities, and

the availability of resources.

The EDRR Framework aims to ensure that the

work of Federal and non-Federal partners is well

coordinated, mutually beneficial, and provides

for the full range of EDRR actions necessary for

successful EDRR.

8 Horizon scanning is the systematic examination of future

potential threats and opportunities that can contribute to the

prioritization of invasive species of concern and the means to

address their introduction and spread (Roy et al. 2014).

9 Priority invasive species will need to be identified. They would

include those that pose the greatest risks to priority landscapes

and aquatic areas, as well as those unforeseen introductions

(i.e., those potentially invasive species not previously identified)

evaluated as high-risk through a rapid science-based risk

assessment process.

Preparedness

Horizon Scanning and Risk Analysis

Planning (Leadership, Communications,

Resources etc.)

Research

Tool Development and Sharing

Monitoring Programs

Rapid Response

Leadership and Coordination

Emergency Containment and Quarantine

Treatment (Eradication)

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting

Communications and Outreach

Early Detection

Training and Monitoring

Detection and Reporting

Identification and Vouchering

Incorporation and Evaluation of

“Sight Unseen” Data

D

ata Recording and Sharing

Communications and Outreach

Rapid Assessment

Rapid Assessment of Species Risks

Risk Management

(Options Identified)

Ri

sk Communications

(Strategy Developed and Employed)

Figure 3: General EDRR Action Steps.

Initial overview of a range of activities

necessary for effective EDRR. See

Appendix B for full descriptions of these

concepts. The roles and responsibilities

of Federal and non-Federal (state/tribal/

other partner) entities vary across this

suite of EDRR actions.

18

Safeguarding America’s Lands and Waters from Invasive Species

Organizational Structure

An effective EDRR Framework requires focused

coordination across the range of Federal and non-

Federal entities to fund and implement prepared-

ness, early detection, rapid assessment, and rapid

response activities. That coordination requires an

organizational structure with well-defined roles and

responsibilities, as well as the means to ensure that

those roles are implemented.

Executive Order 13112 directs that, among other

things, Federal agencies whose actions may af-

fect the status of invasive species shall, to the ex-

tent practicable and permitted by law, and subject

to the availability of appropriations, and within

Administration budgetary limits, use relevant pro-

grams and authorities to detect and respond rap-

idly to and control populations of such species in

a cost-ef

fective and environmentally sound man-

ner. Executive Order 13112 also establishes NISC

10

and directs that it shall provide national leader-

ship regarding invasive species, oversee the imple-

mentation of Executive Order 13112, and see that

Federal agency activities concerning invasive spe-

cies are coordinated, complementary, cost-efficient,

and effective.

It is envisioned that an EDRR T

ask Force (hereafter

Task Force), operating within the NISC structure and

composed of Federal entities and representatives of

states, tribes, and regional initiatives, would serve as

a standing body to facilitate nationwide coordina-

tion among Federal agencies and non-Federal part-

ners. This Task Force would help formalize existing

ad hoc and informal arrangements and would es-

tablish lines of communication between Federal and

non-Federal

partners. Figure 4 outlines a proposed

structure for connecting some of the major EDRR

networks. Appendix C provides examples of existing

invasive species networks that, through effective

partnership and increased capacity, would become

critical components of a national EDRR program.

The Task Force would be informed by ad hoc task

teams that focus on technical issues, including scien-

tific advice (e.g., horizon scanning, risk assessment,

prioritization, specimen identification), capacity

building (e.g., training and protocol development),

communications and outreach (e.g., providing in-

formation about potentially invasive species and

response actions), and operations (e.g., permitting,

information management, training, fund transfer),

but would generally remain a small, agile forum

for improving EDRR ef

fectiveness and coordination.

The Task Force would oversee the development of

Figure 4: Proposed Organizational Struc-

ture of the National EDRR Framework.

The National EDRR Task Force, formed

within the National Invasive Species

Council structure, involves both Federal

and non-Federal entities and supports

and facilitates the critical interfaces

among states, tribes, Federal land man-

agement units, and other entities. These

entities support and further facilitate the

work of site-based partners, who often

are the first to observe and report new

invasive species.

Site-based Partners

States, Tribes, Federal

Agencies, Regional

Entities

National EDRR

Task Force

National Invasive

Species Council

NATIONAL EDRR TASK FORCE

F

ederal and Non-Federal Representation

Executive Team / Ad Hoc Technical Task Teams

National EDRR Coordinator

10 NISC includes the Secretaries or Administrators of 13 Federal Departments and Agencies with the Secretaries of the Interior, Agriculture,

and Commerce serving as co-chairs. The NISC’s responsibilities include the preparation and implementation of a national management

plan, coordination of interagency activities on invasive species, facilitation of information sharing, and encouraging action at local, tribal,

state, and regional levels to achieve the goals of the NISC Management Plan (Executive Order 13112).

19

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

At the site level, there is a more complex interac-

tion of regional bodies, states, tribes, and Federal

agencies with land management units and responsi-

bilities at national and/or state borders. Interaction

across these units is critical. Those specific entities

and their roles will vary according to geography and

invasive species/taxa of concern. Another critical set

of stakeholders are local governments, site-based

partners, and other technical experts (professionals

and amateurs). The role of the Task Force at the site

level will focus on helping link EDRR efforts among

sites (especially monitoring); establishing lines of

communication for information sharing; providing

access to protocols and best practices; and, provid-

ing technical expertise and training.

criteria to identify priority invasive species that may

warrant response as well as develop priority invasive

species watch lists

11

. The Task Force would also over-

see the development of criteria for developing and

evaluating project proposals for EDRR funding (see

Scope of Activities, page 26).

A small executive team of high-level Federal agency

representatives would oversee the Task Force. The

executive team would approve the composition of

the Task Force, designate a National EDRR Coordina-

tor, set priorities, and make funding recommenda-

tions.

11 See footnote 9. The term does not connote an official regulatory or listing status.

Volunteer weed warriors pull bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare) in front of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park.

(photo credit NPS)

This page is intentionally left blank

21

A National Framework for Early Detection and Rapid Response

III. THE EDRR COSTS OF COMBATTING INVASIVE SPECIES

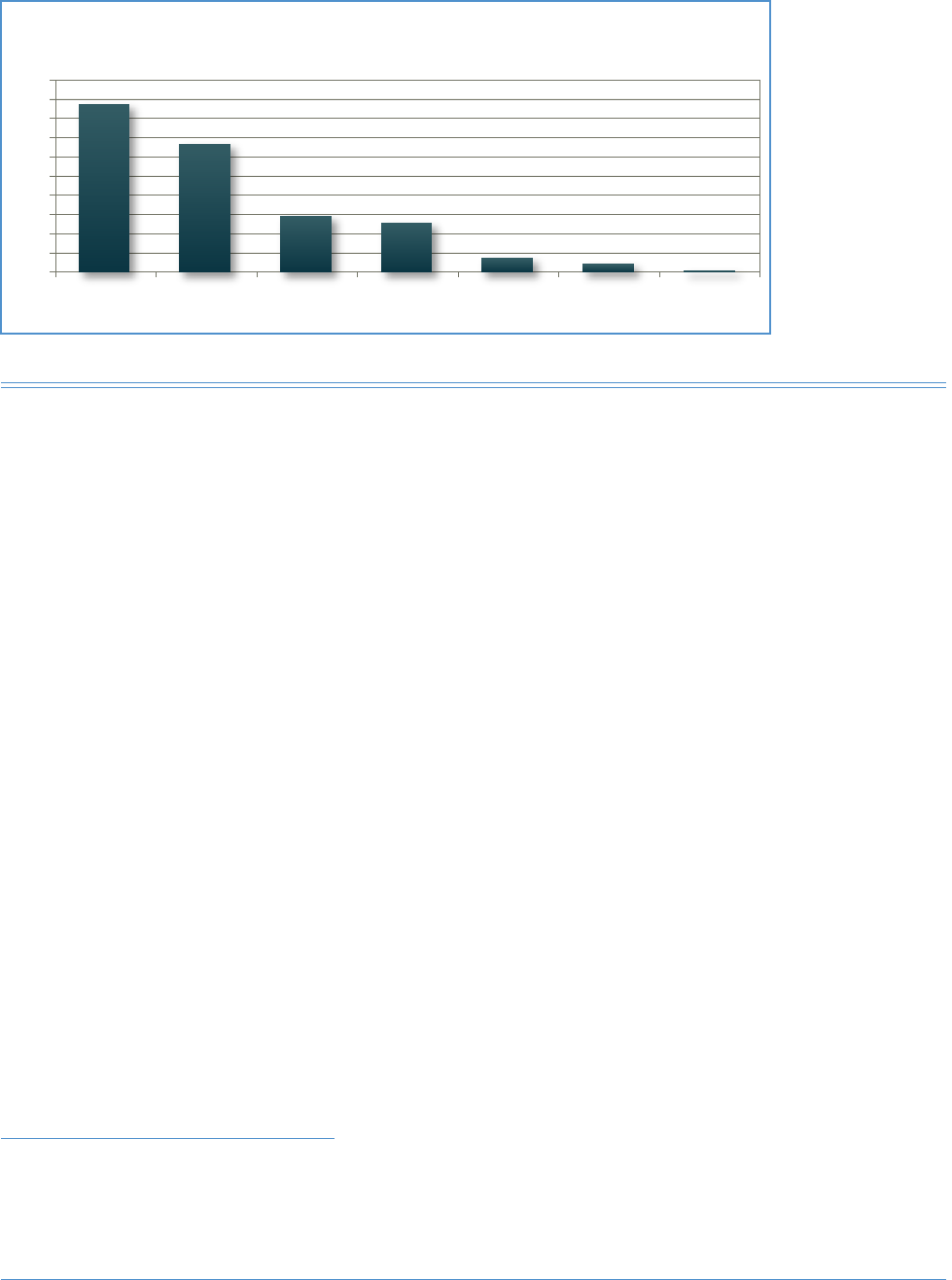

Figure 5: Federal

agency investments

on invasive species

activities across all

taxa, FY 2014 (NISC

2015).

This EDRR Framework views investments in EDRR as

investments in the future of the Nation’s lands and

waters; the economic cost of inaction is expected

to be high, with newly-introduced invasive species

and long-term control of established invasive spe-

cies imposing significant economic and ecological

costs on the Nation. For example, estimates of long-

term control costs, losses, and damages of aquatic

and terrestrial invasive species currently established

in the United States exceed $120 billion per year (Pi-

mentel et al. 2005). The AIS controls cost more than

$9 billion per year (Pimentel 2003). Forest pests and

pathogens cost nearly $1.7 billion in local govern-

ment expenditures and approximately $830 million

in lost residential property values (Aukema et al.

2011).

These figures typically include only monetized dam-

ages that are more easily estimated and often do

not include non-market values, such as the loss of

ecosystem

services, such as flood control, pollina-

tion, and recreation (Cardno ENTRIX and Cohen

2011). In comparison to the cost of these impacts, a

conservative estimate of annual investments by Fed-

eral agencies to address invasive species is estimated

at $2.2 billion across all taxa and stages of the inva-

sion curve. Figure 5 shows the breakdown of invest-

ments according to different categories of activity

with prevention being the largest investment ($872

million for FY 2014), followed by Control and Man-

agement ($670 million for FY 2014), and then EDRR

($290 million for FY 2014) (NISC 2015)

12

. Thus, in-

vestments in EDRR, the second line of defense ac-

cording to the invasion curve (see Fig. 1) receives less

than half of the resources dedicated to longer term

control and management efforts.

Focusing on EDRR, NISC agencies reported a total of

$290 million in investments during FY 2014. USDA

reported approximately $265 million—90 percent

of total Federal investments—the vast majority of

which was allocated to the protection of agriculture

and livestock (see Fig. 6) (NISC 2015).

13

This provides

a sense of scale in terms of the amount of funds di-

rected primarily at EDRR priorities centered on ag-

ricultural, economic, and food security concerns, in

contrast to the funds currently available for EDRR

efforts that would fall under this EDRR Framework.

While Figures 5 and 6 portray total Federal agency

investments in EDRR, it is also useful to get a sense

of the cost of specific EDRR activities. Despite the

disparity, USDA investments are illustrative of the

costs associated with different EDRR activities nec-

essary to implement the EDRR Framework. For early

detection, APHIS received $27.4 million for its Pest

Detection Program in FY 2015.

12 The NISC Interagency Crosscut Budget represents a conservative estimate of spending by NISC member agencies on invasive species. The

Federal budget process is complex, and the crosscut accommodates differences across reporting agencies regarding how they program

their invasive species activities (e.g., set budget lines vs. project or grant funding).

13 There is some crossover of USDA EDRR efforts that also benefit areas outside of agriculture and livestock. For example, work on forest

pests such as Asian longhorned beetle and emerald ash borer benefit natural resources.

1000

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

Control &

Management

Prevention EDRR Education & Public

Awareness

Research Restoration Leadership &

International