ENTERPRISE RISK

MANAGEMENT

Selected Agencies’

Experiences Illustrate

Good Practices in

Managing Risk

Report to the Committee on Oversight

and Government Reform, House of

Representatives

December 2016

GAO-17-63

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-17-63, a report to the

Committee on Oversight and Government

Reform, House of Representatives

December 2016

ENTERPRISE RISK MANAGEMENT

Selected Agencies’ Experiences Illustrate Good

Practices in

Managing Risk

What GAO Found

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is a forward-looking management approach

that allows agencies to assess threats and opportunities that could affect the

achievement of its goals. While there are a number of different frameworks for

ERM, the figure below lists essential elements for an agency to carry out ERM

effectively. GAO reviewed its risk management framework and incorporated

changes to better address recent and emerging federal experience with ERM

and identify the essential elements of ERM as shown below.

GAO has identified six good practices to use when implementing ERM.

Essential Elements and Good Practices of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)

Elements

Good Practices

Align ERM process

to goals and

objectives

Leaders Guide and Sustain ERM Strategy

Implementing ERM requires the full engagement and commitment of senior

leaders, supports the role of leadership in the agency goal setting process,

and demonstrates to agency staff the importance of ERM.

Identify Risks

Develop a Risk-Informed Culture to Ensure All Employees Can

Effectively Raise Risks

Developing an organizational culture to encourage employees to identify and

discuss risks openly is critical to ERM success.

Assess Risks

Integrate ERM Capability to Support Strategic Planning and

Organizational Performance Management

Integrating the prioritized risk assessment into strategic planning and

organizational performance management processes helps improve

budgeting, operational, or resource allocation planning.

Select Risk

Response

Establish a Customized ERM Program Integrated into Existing Agency

Processes

Customizing ERM helps agency leaders regularly consider risk and select

the most appropriate risk response that fits the particular structure and

culture of an agency.

Monitor Risks

Continuously Manage Risks

Conducting the ERM review cycle on a regular basis and monitoring the

selected risk response with performance indicators allows the agency to

track results and impact on the mission, and whether the risk response is

successful or requires additional actions.

Communicate and

Report on Risks

Share Information with Internal and External Stakeholders to Identify

and Communicate Risks

Sharing risk information and incorporating feedback from internal and

external stakeholders can help organizations identify and better manage

risks, as well as increase transparency and accountability to Congress and

taxpayers.

Source: GAO. | GAO-17-63

View GAO-17-63. For more information,

contact J. Christopher Mihm at (202) 512

-

6806

or

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal leaders are responsible for

managing complex and risky missions.

ERM is a way to assist agencies with

managing risk across the organization.

In July 2016, the Office of

Management and Budget (OMB)

issued an updated circular requiring

federal agencies to implement ERM to

ensure federal managers are

effectively managing risks that could

affect the achievement of agency

strategic objectives.

GAO’s objectives were to (1) update its

risk management framework to more

fully include evolving requirements and

essential elements for federal

enterprise risk management, and (2)

identify good practices that selected

agencies have taken that illustrate

those essential elements.

GAO reviewed literature to identify

good ERM practices that generally

aligned with the essential elements

and validated these with subject matter

specialists.

GAO also interviewed officials

representing the 24 Chief Financial

Officer (CFO) Act agencies about ERM

activities and reviewed documentation

where available to corroborate officials’

statements. GAO studied agencies’

practices using ERM and selected

examples that best illustrated the

essential elements and good practices

of ERM.

GAO provided a draft of this report to

OMB and the 24 CFO Act agencies for

review and comment. OMB generally

agreed with the report. Of the CFO act

agencies, 12 provided technical

comments, which GAO included as

appropriate; the others did not provide

any comments.

Page i GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Letter 1

Background 5

Updated ERM Framework Provides Assistance to Agencies as

They Implement ERM 7

Emerging Good Practices Are Being Used at Selected Agencies

to Implement ERM 12

Agency Comments and GAO Responses 43

Appendix I Subject Matter Specialists 45

Appendix II Comments from the Social Security Administration 46

Appendix III Comments from the Department of Veterans Affairs 47

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgements 49

Tables

Table 1: Essential Elements and Associated Good Practices of

Federal Government Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) 13

Table 2: Department of Commerce Roles and Selected

Responsibilities for Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) 20

Table 3: Comparison of Department of Commerce (Commerce)

and National Institute of Standards and Technology

(NIST) Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Reference

Cards25

Figures

Figure 1: Essential Elements of Federal Government Enterprise

Risk Management 8

Figure 2: National Institute of Standards and Technology

Leadership Risk Appetite Survey Scale 18

Contents

Page ii GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Figure 3: Transportation Security Administration Vulnerability

Management Process 23

Figure 4: Department of the Treasury Quarterly Performance

Review Templates 27

Figure 5: Example of an Office of Personnel Management (OPM)

Dashboard for Preparing the Federal Workforce for

Retirement Goal 29

Figure 6. Transportation Security Administration Risk Taxonomy 33

Figure 7: Selected Questions from Commerce’s Enterprise Risk

Management Maturity Assessment Tool (EMAT) 34

Figure 8: Public and Indian Housing Risk and Mitigation Strategies

Dashboard 36

Figure 9: Public and Indian Housing Key Risk Indicators

Dashboard 38

Figure 10: Internal Revenue Service Risk Acceptance Form and

Tool Decision-Making Tool 42

Page iii GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Abbreviations

AFERM Association of Federal Enterprise Risk Management

APG agency priority goals

APMC Agency Program Management Council

CFO Chief Financial Officer

CFOC Chief Financial Officers Council

CIO Chief Information Officer

CMO Chief Management Officer

Commerce Department of Commerce

COO Chief Operating Officer

COSO Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the

Treadway Commission

CRO Chief Risk Officer

DATA Act Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014

DHS Department of Homeland Security

Education Department of Education

EMAT ERM Maturity Assessment Tool

ERM Enterprise Risk Management

ERSC Executive Risk Steering Committee

FMFIA Federal Managers’ Financial Integrity Act

FSA Office of Federal Student Aid

FTE Full-time equivalent

GPRA Government Performance and Results Act

GPRAMA GPRA Modernization Act of 2010

HUD Department of Housing and Urban Development

Interior Department of the Interior

IRS Internal Revenue Service

ISO International Organization for Standardization

IT information technology

JPSS Joint Polar Satellite System

Page iv GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

OCRO Office of the Chief Risk Officer

OMB Office of Management and Budget

OPERM Office of Program Evaluation and Risk Management

OPM Office of Personnel Management

PIC Performance Improvement Council

PIH Office of Public and Indian Housing

PIO Performance Improvement Officer

PwC PricewaterhouseCoopers

QPR quarterly performance review

RAFT Risk Acceptance Form and Tool

RMC Risk Management Council

SSA Social Security Administration

Treasury Department of the Treasury

TSA Transportation Security Administration

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

December 1, 2016

The Honorable Jason Chaffetz

Chairman

The Honorable Elijah E. Cummings

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

Federal government leaders manage complex and inherently risky

missions across their organizations, such as protecting Americans from

health threats, preparing for and responding to natural disasters, building

and managing safe transportation systems, advancing scientific discovery

and space exploration, maintaining a safe workplace, and addressing

security threats. Managing these and other complex challenges, requires

effective leadership and management tools and commitment to delivering

successful outcomes in highly uncertain environments.

While it is not possible to eliminate all uncertainties, it is possible to put in

place strategies to better plan for and manage them. Enterprise Risk

Management (ERM) is one tool that can assist federal leaders in

anticipating and managing risks, as well as considering how multiple risks

in their agency can present even greater challenges and opportunities

when examined as a whole. Risk is the effect of uncertainty on objectives

with the potential for either a negative outcome or a positive outcome or

opportunity. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines ERM

as an effective agency-wide approach to addressing the full spectrum of

the organization’s significant internal and external risks by understanding

the combined impact of risks as an interrelated portfolio, rather than

addressing risks only within silos. An example of an agency enterprise

risk is unfilled mission critical positions across the entire organization that

when examined as a whole could threaten the accomplishment of the

mission.

We first issued our risk management framework in 2005 related to

homeland security efforts for assessing threats and taking appropriate

steps to deal with them.

1

At that time, there was no established

1

GAO, Risk Management: Further Refinements Needed to Assess Risks and Prioritize

Protective Measures at Ports and Critical Infrastructure, GAO-06-91 (Washington, D.C.:

Dec. 15, 2005).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

universally agreed upon set of requirements or processes for a risk

management framework specifically related to homeland security and

combating terrorism. We developed the 2005 framework with five major

phases that helped us assess how the Department of Homeland Security

(DHS) was applying risk management.

In July 2016, OMB issued an update to Circular A-123 requiring federal

agencies to implement ERM to better ensure their managers are

effectively managing risks that could affect the achievement of agency

strategic objectives.

2

Even before OMB required agencies to adopt ERM,

several agencies, after facing significant risks to their mission, were

implementing ERM to address risk-based issues and improve their ability

to respond to future risks. For example:

• The Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA) in the Department of

Education (Education) adopted ERM in 2004, in part, according to

documents we reviewed, to help address long-standing risks including

poor financial management and internal controls, which led us to

place it on our High-Risk List between 1990 and 2005.

3

• The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) adopted an ERM program in

2013 to address issues related to the review of tax-exempt

applications cited in a Department of the Treasury (Treasury)

Inspector General for Tax Administration report that would improve

IRS operations broadly, as well as provide a common framework for

capturing, reporting, and addressing risk areas, and improve the

timeliness of reporting identified risks to the IRS Commissioner, IRS

leaders, and external stakeholders, such as Congress.

4

• The Office of Public and Indian Housing (PIH) at the Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD) finalized its ERM framework

and implementation plans in 2014. This was done in response to

several high profile financial and compliance issues with public

housing authorities, as well as concerns over the completeness of its

2

OMB, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal

Control, Circular No. A-123, (July 15, 2016).

3

In 2005, FSA was removed from our High-Risk List, not just as a result of adopting ERM,

but also through a combination of leadership commitment, capacity to resolve the risk, the

development of a corrective action plan, monitoring of the corrective measures, and

demonstrated progress in resolving the high-risk area.

4

IRS, Charting a Path Forward: Initial Assessment and Plan of Action (Washington, D.C.:

June 24, 2013).

Page 3 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Federal Managers' Financial Integrity Act (FMFIA) certifications

including internal controls and risk management practices, according

to agency officials.

5

We performed our work for this report under the authority of the

Comptroller General to conduct evaluations to assist Congress with its

oversight responsibilities. Our objectives were to (1) update our risk

management framework to more fully include evolving requirements and

essential elements for federal ERM, and (2) identify good practices that

selected agencies were taking that illustrate those essential elements. We

also considered views of subject matter specialists with current

experience in ERM. See appendix I for the list of subject matter

specialists who advised us in our review of the practices.

To adapt our 2005 risk management framework to focus on ERM, we

identified essential elements needed to execute ERM and assist agencies

as they implement and sustain their ERM programs that are generally

consistent with other commonly used ERM frameworks, such as the ISO

31000 Risk Management Principles and Guidelines and the 2004 COSO

Enterprise Risk Management - Integrated Framework.

6

When we shared

these essential elements with subject matter specialists, they confirmed

that they represent the critical elements of the ERM process.

To identify good practices in using ERM, we analyzed and synthesized

ERM literature using ProQuest, First Search, and Scopus bibliographic

databases in public and business sources.

7

We validated these good

practices with subject matter specialists with knowledge specific to the

use of ERM in government settings, and, based on their suggestions, we

refined the practices. We then considered the essential elements of ERM

relative to our identified good practices and determined how these

5

31 U.S.C. § 3512.7

6

International Organization for Standardization (ISO), ISO 31000-Risk Management

Principles and Guidelines, (ISO, Nov.15, 2009), and Committee of Sponsoring

Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), and COSO, Enterprise Risk

Management-Integrated Framework, 2004. COSO has since updated ERM framework,

Enterprise Risk Management-Aligning Strategy with Performance, exposure draft issued

in June 2016, but we did not include this in our analysis.

7

In the bibliographic database search, we used the following terms, enterprise risk

management, best practices, leading practices, government, and public sector, for years

2005 through 2015, and searched in scholarly and trade journals, conference

proceedings, and dissertations and theses.

Page 4 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

practices generally fit with the essential elements as a way to assist

agencies as they implemented ERM.

To identify what agencies were doing consistent with our essential

elements and how their good practices were used in implementing ERM,

we used a semi-structured interview protocol and spoke with officials

representing 21 of the 24 executive branch agencies covered in the Chief

Financial Officers (CFO) Act of 1990, as amended.

8

Three agencies did

not participate in interviews but provided us with written responses to our

questions, including the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior and

the Social Security Administration. We asked each of the 24 agencies

whether or not the agency had ERM in place and their perspectives on

ERM.

To identify case illustrations of the good practices, we reviewed

information from agency interviews and documentation they provided

about their ERM practices. From the ERM practices of 24 CFO Act

agencies and their component agencies, we selected examples that best

illustrated our essential elements and good practices. In conducting the

case illustrations, we interviewed agency officials and reviewed agency

documentation about their use of ERM. We selected examples from nine

agencies including the Department of Commerce (Commerce) and its

component bureaus the National Institute of Standards and Technology

(NIST) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA), DHS’s Transportation Security Administration (TSA), PIH, the

Office of Personnel Management (OPM), Treasury and the IRS, and FSA.

We also interviewed OMB officials from the offices involved in the update

of Circular A-123, the Office of Performance and Personnel Management

and the Office of Federal Financial Management, to gain their

perspectives on agencies’ implementation of ERM.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2015 to December 2016

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

8

31 U.S.C. § 901(b). The 24 CFO Act agencies, generally the largest federal agencies,

are the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and

Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior,

Justice, Labor, State, Transportation, the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs, as well as the

Agency for International Development, Environmental Protection Agency, General

Services Administration, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Science

Foundation, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Office of Personnel Management, Small

Business Administration, and Social Security Administration.

Page 5 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

ERM allows management to understand an organization’s portfolio of top-

risk exposures, which could affect the organization’s success in meeting

its goal. As such, ERM is a decision-making tool that allows leadership to

view risks from across an organization’s portfolio of responsibilities. ERM

recognizes how risks interact (i.e., how one risk can magnify or offset

another risk), and also examines the interaction of risk treatments

(actions taken to address a risk), such as acceptance or avoidance. For

example, treatment of one risk in one part of the organization can create

a new risk elsewhere or can affect the effectiveness of the risk treatment

applied to another risk. ERM is part of overall organizational governance

and accountability functions and encompasses all areas where an

organization is exposed to risk (financial, operational, reporting,

compliance, governance, strategic, reputation, etc.).

In July 2016, OMB updated its Circular No. A-123 guidance to establish

management’s responsibilities for ERM, as well as updates to internal

control in accordance with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal

Government.

9

OMB also updated Circular No. A-11, Preparation,

Submission, and Execution of the Budget in 2016 and refers agencies to

Circular No. A-123 for implementation requirements for ERM.

10

Circular

No. A-123 guides agencies on how to integrate organizational

performance and ERM to yield an “enterprise-wide, strategically-aligned

portfolio view of organizational challenges that provides better insight

about how to most effectively prioritize resource allocations to ensure

successful mission delivery.” The updated requirements in Circulars A-

123 and A-11 help modernize existing management efforts by requiring

agencies to implement an ERM capability coordinated with the strategic

planning and strategic review process established by the GPRA

Modernization Act of 2010 (GPRAMA), and with the internal control

processes required by the FMFIA and in our Standards for Internal

9

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G

(Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

10

OMB, Circular No. A-11, Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget pt 6,§§

270 (July 2016).

Background

Page 6 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Control in the Federal Government.

11

This integrated governance

structure is designed to improve mission delivery, reduce costs, and focus

corrective actions towards key risks.

More specifically, Circular No. A-123 discusses both internal control and

ERM and how these fit together to manage agency risks. Our Standards

for Internal Control in the Federal Government describes internal control

as a process put in place by an entity’s oversight body, management, and

other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that objectives

related to operations, compliance, and reporting will be achieved, and

serves as the first line of defense in safeguarding assets.

12

Internal

control is also part of ERM and used to manage or reduce risks in an

organization. Prior to implementing ERM, risk management focused on

traditional internal control concepts to managing risk exposures. Beyond

traditional internal controls, ERM promotes risk management by

considering its effect across the entire organization and how it may

interact with other identified risks.

13

Additionally, ERM also addresses

other topics such as setting strategy, governance, communicating with

stakeholders, and measuring performance, and its principles apply at all

levels of the organization and across all functions.

14

Implementation of OMB circulars is expected to engage all agency

management, beyond the traditional ownership of A-123 by the Chief

Financial Officer community. According to the A-123 Circular, it requires

leadership from the agency Chief Operating Officer (COO) and

Performance Improvement Officer (PIO) or other senior official with

responsibility for the enterprise, and close collaboration across all agency

mission and mission-support functions.

15

The A-123 guidance also

11

Pub. L. No. 111-352, 124 Stat. 3866 (Jan. 4, 2011).

12

GAO-14-704G.

13

For additional discussion about ERM in the federal government, see Dr. Karen Hardy,

Enterprise Risk Management, A Guide for Government Professionals, (San Francisco,

CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015), and Thomas H. Stanton and Douglas W. Webster,

Managing Risk and Performance, (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014).

14

See COSO, Enterprise Risk Management-Aligning Strategy with Performance, exposure

draft issued in June 2016, for additional information on ERM and its relationship to internal

controls.

15

Agencies are required to designate a senior executive within the agency as a

Performance Improvement Officer (PIO), who reports directly to the COO and has

responsibilities to assist the agency head and COO with performance management

activities.

Page 7 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

requires agencies to create a risk profile that helps them identify and

assess risks arising from mission and mission-support operations, and

consider those risks as part of the annual strategic review process.

Circular A-123 requires that agencies’ risk profiles include risks to

strategic, operations, reporting and compliance objectives.

A federal interagency group of ERM practitioners developed a Playbook

released through the Performance Improvement Council (PIC) and the

Chief Financial Officers Council (CFOC) in July 2016 to provide federal

agencies with a resource to support ERM.

16

In particular, the Playbook

assists them in implementing the required elements in the updated A-123

Circular.

17

To assist agencies in better assessing challenges and opportunities from

an enterprise-wide view, we have updated our risk management

framework first published in 2005 to more fully include recent experience

and guidance, as well as specific enterprise-wide elements.

18

As

mentioned previously, our 2005 risk management framework was

developed in the context of risks associated with homeland security and

combating terrorism. However, increased attention to ERM concepts and

their applicability to all federal agencies and missions led us to revise our

risk framework to incorporate ERM concepts that can help leaders better

address uncertainties in the federal environment, changing and more

complex operating environments due to technology and other global

factors, the passage of GPRAMA and its focus on overall performance

improvement, and stakeholders seeking greater transparency and

accountability. For many similar reasons, the Committee of Sponsoring

Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) initiated an effort to

update its ERM framework for 2016, and the International Organization

16

U.S. CFO Council and Performance Improvement Council, Playbook: Enterprise Risk

Management for the U.S. Federal Government, (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 29, 2016).

17

GPRAMA established the Performance Improvement Council (PIC) in law and included

additional responsibilities. The PIC is charged with assisting OMB to improve the

performance of the federal government. Among its other responsibilities, the PIC is to

facilitate the exchange among agencies of useful performance improvement practices and

work to resolve government-wide or crosscutting performance issues. The Chief Financial

Officers Council (CFOC) is comprised of federal CFOs, senior officials at OMB, and the

U.S. Treasury to address the critical issues in federal financial management with

collaborative leadership

18

GAO-06-91.

Updated ERM

Framework Provides

Assistance to

Agencies as They

Implement ERM

Page 8 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

for Standardization (ISO) plans to update its ERM framework in 2017.

Further, as noted, OMB has now incorporated ERM into Circulars A-11

and A-123 to help improve overall agency performance.

We identified six essential elements to assist federal agencies as they

move forward with ERM implementation. Figure 1 below shows how

ERM’s essential elements fit together to form a continuing process for

managing enterprise risks. The absence of any one of the elements

below would likely result in an agency incompletely identifying and

managing enterprise risk. For example, if an agency did not monitor risks,

then it would have no way to ensure that it had responded to risks

successfully. There is no “one right” ERM framework that all organizations

should adopt. However, agencies should include certain essential

elements in their ERM program.

Figure 1: Essential Elements of Federal Government Enterprise Risk Management

Page 9 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Below we describe each essential element in more detail, why it is

important, and some actions necessary to successfully build an ERM

program.

1. Align the ERM process to agency goals and objectives. Ensure

the ERM process maximizes the achievement of agency mission and

results. Agency leaders examine strategic objectives by regularly

considering how uncertainties, both risks and opportunities, could

affect the agency’s ability to achieve its mission. ERM subject matter

specialists confirmed that this element is critical because the ERM

process should support the achievement of agency goals and

objectives and provide value for the organization and its stakeholders.

By aligning the ERM process to the agency mission, agency leaders

can address risks via an enterprise-wide, strategically-aligned portfolio

rather than addressing individual risks within silos. Thus, agency

leaders can make better, more effective decisions when prioritizing

risks and allocating resources to manage risks to mission delivery.

While leadership is integral throughout the ERM process, it is an

especially critical component of aligning ERM to agency goals and

objectives because senior leaders have an active role in strategic

planning and accountability for results.

2. Identify risks. Assemble a comprehensive list of risks, both threats

and opportunities, that could affect the agency from achieving its

goals and objectives. This element of ERM systematically identifies

the sources of risks as they relate to strategic objectives by examining

internal and external factors that could affect their accomplishment. It

is important that risks either can be opportunities for, or threats to,

accomplishing strategic objectives. The literature we reviewed, as well

as subject matter specialists, pointed out that identifying risks in any

organization is challenging for employees, as they may be concerned

about reprisals for highlighting "bad news."

Risks to objectives can often be grouped by type or category. For

example, a number of risks may be grouped together in categories

such as strategic, program, operational, reporting, reputational,

technological, etc. Categorizing risks can help agency leaders see

how risks relate and to what extent the sources of the risks are

similar. The risks are linked to relevant strategic objectives and

documented in a risk register or some other comprehensive format

that also identifies the relevant source and a risk owner to manage the

treatment of the risk. Comprehensive risk identification is critical even

if the agency does not control the source of the risk. The literature and

subject matter specialists we consulted told us that it is important to

Page 10 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

build a culture where all employees can effectively raise risks. It is

also important for the risk owner to be the person who is most

knowledgeable about the risk, as this person is likely to have the most

insight about appropriate ways to treat the risk.

3. Assess risks. Examine risks considering both the likelihood of the

risk and the impact of the risk on the mission to help prioritize risk

response. Agency leaders, risk owners, and subject matter experts

assess each risk by assigning the likelihood of the risk’s occurrence

and the potential impact if the risk occurs. It is important to use the

best information available to make the risk assessment as realistic as

possible. Risk owners may be in the best position to assess risks.

Risks are ranked based on organizational priorities in relation to

strategic objectives. Risks are ranked based on organizational

priorities in relation to strategic objectives. Agencies need to be

familiar with the strengths of their internal control when assessing

risks to determine whether the likelihood of a risk event is higher or

lower based on the level of uncertainty within the existing control

environment. Senior leaders determine if a risk requires treatment or

not. Some identified risks may not require treatment at all because

they fall within the agency's risk appetite, defined as how much risk

the organization is willing to accept relative to mission achievement.

The literature we reviewed and subject matter specialists noted that

integrating ERM efforts with strategic planning and organizational

performance management would help an organization more

effectively assess its risks with respect to the impact on the mission.

4. Select risk response. Select a risk treatment response (based on

risk appetite) including acceptance, avoidance, reduction, sharing, or

transfer. Agency leaders review the prioritized list of risks and select

the most appropriate treatment strategy to manage the risk. When

selecting the risk response, subject matter experts noted that it is

important to involve stakeholders that may also be affected, not only

by the risk, but also by the risk treatment. Subject matter specialists

also told us that when agencies discuss proposed risk treatments,

they should also consider treatment costs and benefits. Not all

treatment strategies manage the risk entirely; there may be some

residual risk after the risk treatment is applied. Senior leaders need to

decide if the residual risk is within their risk appetite and if additional

treatment will be required. The risk response should also fit into the

management structure, culture, and processes of the agency, so that

ERM becomes an integral part of regular management functions. One

subject matter specialist suggested that maximize opportunity should

also be included as a risk treatment response, so that leaders may

Page 11 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

capture the positive outcomes or opportunities associated with some

risks.

5. Monitor Risks. Monitor how risks are changing and if responses are

successful. After implementing the risk response, agencies must

monitor the risk to help ensure that the entire risk management

process remains current and relevant. The literature we reviewed also

suggests using a risk register or other comprehensive risk report to

track the success of the treatment for managing the risk. Senior

leaders and risk owners review the effectiveness of the selected risk

treatment and change the risk response as necessary. Subject matter

specialists noted that a good practice includes continuously

monitoring and managing risks. Monitoring should be a planned part

of the ERM process and can involve regular checking as part of

management processes or part of a periodic risk review. Senior

leaders also could use performance measures to help track the

success of the treatment, and if it has had the desired effect on the

mission.

6. Communicate and Report on Risks. Communicate risks with

stakeholders and report on the status of addressing the risks.

Communicating and reporting risk information informs agency

stakeholders about the status of identified risks and their associated

treatments, and assures them that agency leaders are managing risk

effectively. In a federal setting, communicating risk is important

because of the additional transparency expected by Congress,

taxpayers, and other relevant stakeholders. Communicating risk

information through a dedicated risk management report or integrating

risk information into existing organizational performance management

reports, such as the annual performance and accountability report,

may be useful ways of sharing progress on the management of risk.

The literature we reviewed showed and subject matter specialists

confirmed that sharing risk information is a good practice. However,

concerns may arise about sharing overly specific information or risk

responses that would rely on sensitive information. Safeguards should

be put in place to help secure information that requires careful

management, such as information that could jeopardize security,

safety, health, or fraud prevention efforts. In this case, agencies can

help alleviate concerns by establishing safeguards, such as

communicating risk information only to appropriate parties, encrypting

sensitive data, authorizing users' level of rights and privileges, and

providing information on a need-to-know basis.

Page 12 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

We identified six good practices that nine agencies are implementing that

illustrate ERM’s essential elements. The selected good practices are not

all inclusive, but represent steps that federal agencies can take to initiate

and sustain an effective ERM process, as well as practices that can apply

to more advanced agencies as their ERM processes mature. We expect

that as federal experiences with ERM evolve, we will be able to refine

these practices and identify additional ones.

Below in table 1, we identify the essential elements of ERM and the good

practices that support each particular element that agencies can use to

support their ERM programs. The essential elements define what ERM is

and the good practices and case illustrations described in more detail

later in this report provide ways that agencies can effectively implement

ERM. The good practices may fit with more than one essential element,

but are shown in the table next to the element to which they most closely

relate.

Emerging Good

Practices Are Being

Used at Selected

Agencies to

Implement ERM

Page 13 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Table 1: Essential Elements and Associated Good Practices of Federal Government Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)

Element

Good Practice

Align ERM process to goals and objectives

Ensure the ERM process maximizes the

achievement of agency mission and results.`

Leaders Guide and Sustain ERM Strategy

Implementing ERM requires the full engagement and commitment of senior

leaders, which supports the role of leadership in the agency goal setting process,

and demonstrates to agency staff the importance of ERM.

Identify Risks

Assemble a comprehensive list of risks, both

threats and opportunities, that could affect the

agency from achieving its goals and objectives.

Develop a Risk-Informed Culture to Ensure All Employees Can Effectively

Raise Risks

Developing an organizational culture to encourage employees to identify and

discuss risks openly is critical to ERM success.

Assess Risks

Examine risks considering both the likelihood of

the risk and the impact of the risk to help

prioritize risk response.

Integrate ERM Capability to Support Strategic Planning and Organizational

Performance Management

Integrating the prioritized risk assessment into strategic planning and

organizational performance management processes helps improve budgeting,

operational, or resource allocation planning.

Select Risk Response

Select risk treatment response (based on risk

appetite) including acceptance, avoidance,

reduction, sharing, or transfer.

Establish a Customized ERM Program Integrated into Existing Agency

Processes

Customizing ERM helps agency leaders regularly consider risk and select the most

appropriate risk response that fits the particular structure and culture of an agency.

Monitor Risks

Monitor how risks are changing and if responses

are successful.

Continuously Manage Risks

Conducting the ERM review cycle on a regular basis and monitoring the selected

risk response with performance indicators allows the agency to track results and

impact on the mission, and whether the risk response is successful or requires

additional actions.

Communicate and Report on Risks

Communicate risks with stakeholders and report

on the status of addressing the risk.

Share Information with Internal and External Stakeholders to Identify and

Communicate Risks

Sharing risk information and Incorporating feedback from internal and external

stakeholders can help organizations identify and better manage risks, as well as

increase transparency and accountability to Congress and taxpayers.

Source: GAO. | GAO-17-63

The following examples illustrate how selected agencies are guiding and

sustaining ERM strategy through leadership engagement. These include

how they have:

• designated an ERM leader or leaders

• committed organization resources to support ERM, and

• set organizational risk appetite.

This good practice relates most closely to Align ERM Process to Goals

and Objectives as shown in table 1.

Good Practice: Guide and

Sustain ERM Strategy

through Leadership

Engagement

Page 14 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

According to the Chief Financial Officer’s Council (CFOC) and

Performance Improvement Council (PIC) Playbook, strong leadership at

the top of the organization, including active participation in oversight, is

extremely important for achieving success in an ERM program. To

manage ERM activities, leadership may choose to designate a Chief Risk

Officer (CRO) or other risk champion to demonstrate the importance of

risk management to the agency and to implement and manage an

effective ERM process across the agency. The CRO role includes leading

the ERM process; involving those that need to participate and holding

them accountable; ensuring that ERM reviews take place regularly;

obtaining resources, such as data and staff support if needed; and

ensuring that risks are communicated appropriately to internal and

external stakeholders, among other things. For example, at TSA, the

CRO serves as the principal advisor on all risks that could affect TSA’s

ability to perform its mission, according to the August 2014 TSA ERM

Policy Manual. The CRO reports directly to the TSA Administrator and the

Deputy Administrator. In conjunction with the Executive Risk Steering

Committee (ERSC) composed of Assistant Administrators who lead

TSA’s program and management offices, the CRO leads TSA in

conducting regular enterprise risk assessments of TSA business

processes or programs, and overseeing processes that identify, assess,

prioritize, respond to, and monitor enterprise risks.

19

Specifically, the August 2014 TSA ERM Policy Manual describes ERSC’s

role to “oversee the development and implementation of processes used

to analyze, prioritize, and address risks across the agency including

terrorism threats facing the transportation sector, along with non-

operational risks that could impede its ability to achieve its strategic

objectives.” The TSA CRO told us that its ERSC provides an opportunity

for all Assistant Administrators to get together to have risk conversations.

For example, the CRO recently recommended that the ERSC add

implementation of the agency’s new financial management system to the

risk register.

19

Assistant Administrators on the ERSC are from the offices of Acquisition, Finance and

Administration, Human Capital, Information Technology, Global Strategies, Intelligence

and Analysis, Law Enforcement/Federal Air Marshal Service, Security Capabilities,

Security Operations, and Security Policy and Industry Engagement, Training and

Development, Professional Responsibility, Legislative Affairs, Strategic Communication

and Public Affairs, Investigations, Civil Rights and Chief Counsel.

TSA’s ERM Process Is Led by

a Chief Risk Officer and

Senior

-Level Executive Risk

Steering Committee

Page 15 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

According to the CRO, the system’s implementation was viewed as the

responsibility of the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and Chief Information

Officer (CIO). However, the implementation needed to be managed at the

enterprise-level because if it was not successfully implemented, the entire

enterprise would be affected. The CRO proposed adding the

implementation of the new financial management system to the TSA risk

register to give the issue broader visibility. The ERSC unanimously

concurred with the recommendation, and staff from the Office of Finance

and Administration—the risk owner—will brief the ERSC periodically on

the status of the effort.

According to TSA’s ERM Policy Manual, the CRO leads the overall ERM

process, while the ERSC brings knowledge and expertise from their

individual organizations to help identify and prioritize risks and

opportunities of TSA’s overall approach to operations. While the CRO and

ERSC play critical roles in ERM oversight, the relevant program offices

still own risks and execute risk management, according to the TSA ERM

Policy Manual.

To launch and sustain a successful ERM program, organizational

resources are needed to help implement leadership’s vision of ERM for

the agency and ensure its ongoing effectiveness. For example, when FSA

began its ERM program in 2004, the Chief Operating Officer (COO)

decided to hire a CRO and give him full responsibility to establish the

ERM organization and program and implement it across the organization.

According to documents we reviewed, the CRO dedicated resources to

define the goal and purpose of the ERM program and met with key

leaders across the agency to socialize the program. Agency leadership

hired staff to establish the ERM program and provided risk management

training to business unit senior leaders and their respective staff. Our

review of documents shows that the FSA continues to provide ERM

training to senior staff and all FSA employees and also participates in an

annual FSA Day, so employees can learn more about all business units

across FSA including the Risk Management Office and its ERM

implementation. In September 2016, the FSA CRO told us that the Risk

Management Office had a staff of 19 full-time equivalent (FTE)

FSA Committed Resources to

Support ERM

Page 16 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

employees.

20

FSA continues to provide resources to its ERM program

and has subsequently structured its leadership by involving two senior

leaders and a risk management committee to manage ERM processes.

According to the CRO, its risk committee guides the ERM process, tracks

the agency’s progress in managing risks, and increases accountability for

outcomes.

Both the CRO, the Chairman of the Risk Management Committee and the

Senior Risk Advisor report directly to the FSA Chief Operating Officer

(COO). The CRO manages the day-to-day aspects of assessing risks for

various internal FSA operations, programs and initiatives, as well as

targeting risk assessments on specific high-risk issues, such as the

closing of a large for-profit school. The Chairman of the Risk

Management Committee and the Senior Risk Advisor advise the COO by

identifying and analyzing external risks that could affect the

accomplishment of FSA’s strategic objectives. The Senior Risk Advisor

also gathers and disseminates information internally that relates to FSA

risk issues, such as cybersecurity or financial issues. In addition, he

serves as the Chair of the Risk Management Committee and leads its

monthly meetings.

Other senior leaders and members involved with the Risk Management

Committee were drawn from across the agency and demonstrate the

importance of ERM to FSA. Specifically, the committee is chaired by the

independent senior risk advisor and comprised of the CRO, COO, CFO,

Chief Information Officer (CIO), General Manager of Acquisitions, Chief

Business Operations Officer, Chief of Staff, Chief Compliance Officer,

Deputy COO, and Chief Customer Experience Officer, and meets

monthly. Agency officials said that the participation of the COO, along

with that of the other functional chiefs, indicates ERM’s importance and

the commitment of staff—namely these executives–in the effort.

20

According to OMB, Preparation, Submission and Execution of the Budget, OMB Circular

A-11 (July 1, 2016), FTE employment means the total number of regular straight-time

hours worked (i.e., not including overtime or holiday hours worked) by employees divided

by the number of compensable hours applicable to each fiscal year. Annual leave, sick

leave, compensatory time off and other approved leave categories are considered “hours

worked” for purposes of defining full-time equivalent employment that is reported in the

employment summary.

Page 17 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

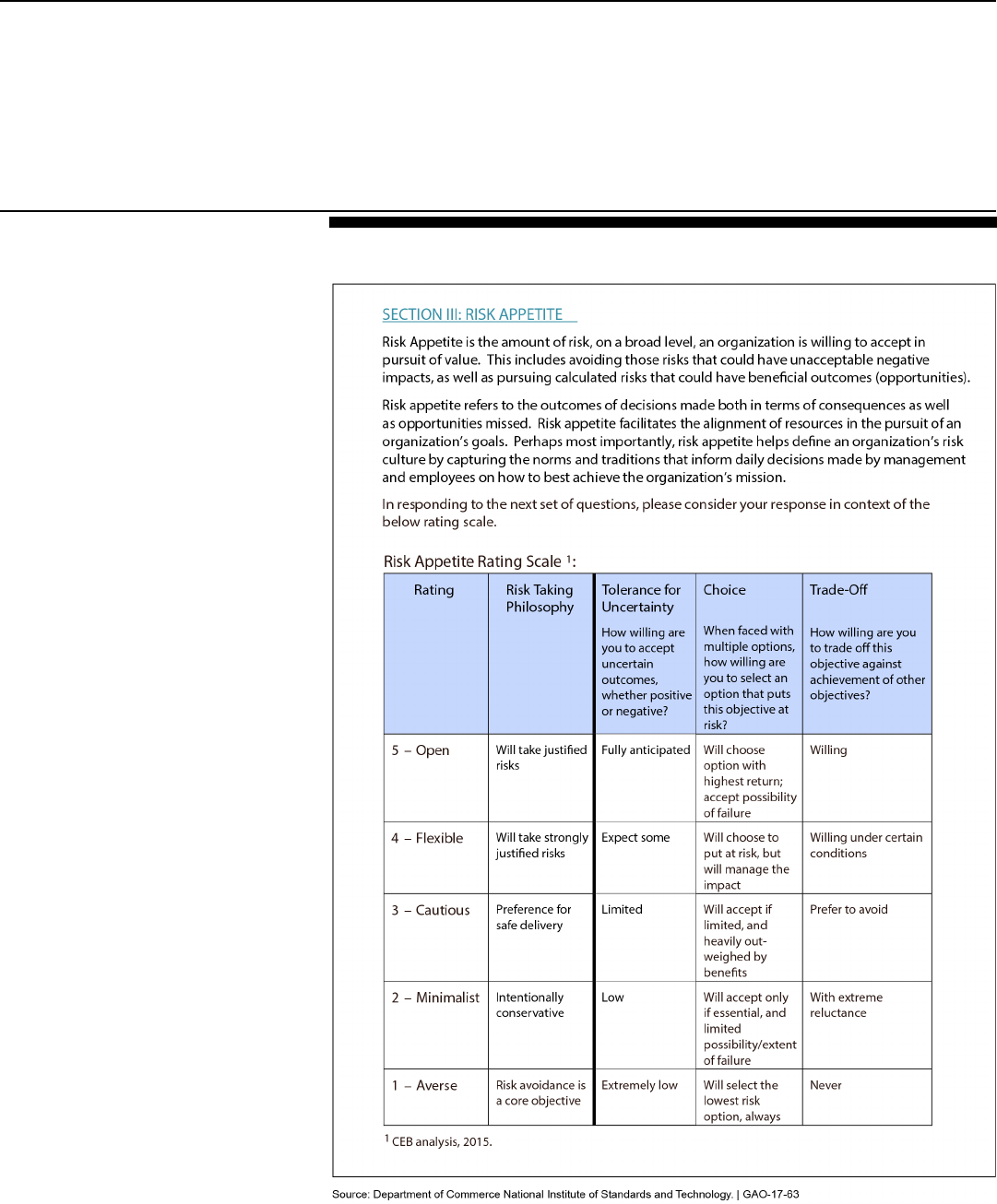

Developing an agency risk appetite requires leadership involvement and

discussion. The organization should develop a risk appetite statement

and embed it in policies, procedures, decision limits, training, and

communication, so that it is widely understood and used by the agency.

Further, the risk appetite may vary for different activities depending on the

expected value to the organization and its stakeholders. To that end, the

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) ERM Office

surveyed its 33-member senior leadership team to measure risk appetite

among its senior leaders. Without a clearly defined risk appetite, NIST

could be taking risks well beyond management’s comfort level, or passing

up strategic opportunities by assuming its leaders were risk averse. The

survey objectives were to “assess management familiarity and use of risk

management principles in day-to-day operations and to solicit

management perspectives and input on risk appetite, including their

opinions on critical thresholds that will inform the NIST enterprise risk

criteria.”

Survey questions focused on the respondent’s self-reported

understanding of a variety of risk management concepts and asked

respondents to rate how they consider risk with respect to management,

safety, and security. The survey assessed officials’ risk appetite across

five areas: NIST Goal Areas, Strategic Objectives, Core Products and

Services, Mission Support Functions, and Core Values. See figure 2 for

the rating scale that NIST used to assess officials’ appetite for risk in

these areas.

National Institute of Standards

and Technology Surveyed

Leaders

’ Views of Risk

Appetite

Page 18 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Figure 2: National Institute of Standards and Technology Leadership Risk Appetite

Survey Scale

Page 19 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

The survey results revealed a disconnect between the existing and

desired risk appetite for mission support functions. According to NIST

officials, respondents believed the bureau needed to accept more risk to

allow for innovation within mission support functions. According to

agency officials, to better align risk appetite with mission needs, the NIST

Director tasked the leadership team with developing risk appetite levels

for those areas with the greatest disagreement between the existing and

desired risk appetite, while still remaining compliant with laws and

regulations. Agency officials told us the NIST ERM Office plans to

address this topic via further engagement with senior managers and

subject matter experts.

The following examples illustrate how selected agencies are developing a

risk-informed culture, including how they have:

• encouraged employees to discuss risks openly,

• trained employees on ERM approach

• engaged employees in ERM efforts, and

• customized ERM tools for organizational mission and culture.

This good practice relates most closely to Identify Risks, one of the

Essential Elements of Federal Government ERM shown in table 1.

Successful ERM programs find ways to develop an organizational culture

that allows employees to openly discuss and identify risks, as well as

potential opportunities to enhance organizational goals or value. The

CFOC and PIC Playbook also supports this notion that once ERM is built

into the agency culture, the agency can learn from managed risks or, near

misses, using them to improve how it identifies and analyzes risk. For

example, Commerce officials sought to embed a culture of risk

awareness across the department by defining cascading roles of

leadership and responsibility for ERM across the department and for its

12 bureaus. Additionally, an official noted that Commerce leveraged this

forum to share bureau best practices; develop a common risk lexicon;

and address cross-bureau risks, issues and concerns regarding ERM

practice and implementation. According to the updated ERM program

policy, these roles should support the ERM program and promote a risk

management culture. They also help promote transparency, oversight,

and accountability for a successful ERM program.

Good Practice: Develop a

Risk-Informed Culture to

Ensure All Employees Can

Effectively Raise Risks

Commerce Defined Roles and

Responsibilities Across the

Ag

ency to Build a Risk

Management Culture and

Guide Its ERM Process

Page 20 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Table 2 shows the ERM roles and set of responsibilities within Commerce

and how they support a culture of risk awareness at each level.

Table 2: Department of Commerce Roles and Selected Responsibilities for Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)

Department Level

Role

Selected Responsibilities

Executive Governance Committee composed of senior level

department representatives

Provide policy and management oversight and advice regarding ERM

implementation and operations; facilitate governance and risk

consideration as element of department decision-making; inform

department management of progress towards ERM maturity and

efficacy of policy

Risk Management Council

Recommend and advise on development and implementation of

processes for identifying, assessing, treating, monitoring, and reporting

organizational risks; foster sound risk management practices

throughout the department

Office of Program Evaluation and Risk Management

(OPERM)

Leads the department in increasing knowledge and understanding of

risk; coordinate risk management efforts; monitor execution of

enterprise risk policy across the department

Bureaus and Departmental Offices

Carry out risk management processes and integrate into day-to-day

operations as a means of institutionalizing risk management across

the department

Office of Financial Management

Oversee, assess, and test internal controls over financial reporting as

part of the requirements outlined in Appendix A of OMB Circular A-123

Bureau Level

Role

Selected Responsibilities

Bureau Heads

Appoint a Risk Management Officer; ensure bureau implements ERM

in accordance with policy; ensure timely submission of annual

assurance statement required by the Federal Managers’ Financial

Integrity Act

Risk Management Officers

Serve as champions for overseeing implementation, integration, and

management of ERM framework within bureau; serve on department

Risk Management Council; update bureau risk inventory annually and

elevate common or department-level risks to OPERM as needed;

oversee, assess, and report on bureau ERM maturity annually

Managers and Supervisors

Ensure that those with risk management responsibilities are properly

trained and that employees are aware of and follow sounds risk

management policies and practices

Employees

Manage risk within their area of responsibility

Source: Department of Commerce | GAO-17-63.

To successfully implement and sustain ERM, it is critical that staff, at all

levels, understand how the organization defines ERM, its subsequent

ERM approach, and organizational expectations on their involvement in

the ERM process. The CFOC and PIC Playbook also supports risk

awareness as previously stated because once ERM is built into the

HUD ERM Training

Emphasized Culture Changes

Needed to Raise Risks

Page 21 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

agency culture, it can be possible to learn from managed risks and near

misses when risks materialize, and then used to improve the process of

identifying and analyzing risk in the future. Further, the Playbook

suggests that this culture change can only occur if top agency leaders

champion ERM and encourage the flow of information needed for

effective decision making. For example, to promote cultural change and

encourage employees to raise risks, PIH trained about half of its 1,500

employees in 2015. Agency officials told us that they plan to expand on

the 2015 training and provide training to all PIH employees after 2016.

The in-person PIH training includes several features of our identified ERM

good practices, such as leadership support and the importance of

developing a risk-informed culture. For example, the Principal Deputy

Assistant Secretary for PIH was visibly involved in the training and kicked

off the first of the five training modules using a video emphasizing ERM.

The training contained discussions and specific exercises dedicated to

the importance of raising and assessing risks and understanding the

leadership and employee roles in ERM. The first training module

emphasized the factors that can support ERM by highlighting the

following cultural characteristics.

• ERM requires a culture that supports the reporting of risks.

• ERM requires a culture of open feedback.

• A risk-aware culture enables all HUD staff to speak up and then be

listened to by decision-makers.

• Leadership encourages the sharing of risks.

By focusing on the importance of developing a risk aware culture in the

first ERM training module, PIH officials emphasized that ERM requires a

cultural transformation for its success. To enable all employees to

participate and benefit from the training, PIH officials recorded the

modules and made them available on You-Tube.

Our literature review found that building a risk-aware culture supports the

ERM process by encouraging staff across the organization to feel

comfortable raising risks. Involving employees in identifying risks allows

the agency to increase risk awareness and generate solutions to those

identified risks. Some ways to strengthen this culture include the

presence of risk management communities of practice, the development

and dissemination of a risk lexicon agencywide, and conducting forums

that enable frontline staff to raise risk-related strategic or operational

concerns with leadership and senior management. For example, TSA’s

TSA Sponsored Several

Programs t

o Raise Risk

Awareness Among Employees

Page 22 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Office of the Chief Risk Officer (OCRO) has sponsored a number of

activities related to raising risk awareness.

First, TSA has established a risk community of interest open to any

employee in the organization, and has hosted speakers on ERM topics.

These meetings have provided an opportunity for employees across the

administration to learn and discuss risks and become more

knowledgeable about the types of issues that should be raised to

management.

Second, TSA created a risk lexicon, so that all staff involved with ERM

would use and understand risk terminology similarly. The lexicon

describes core concepts and terms that form the basis for the TSA ERM

framework. TSA incorporated the ERM lexicon into the TSA ERM Policy

Manual.

Third, in January 2016, TSA started a vulnerability management process

for offices and functions with responsibility for identifying or addressing

security vulnerabilities. Officials told us that this new process is intended

to help raise risks from the bottom up so that they receive top level

monitoring. According to the December 2015 TSA memo we reviewed,

the process centralizes tracking of vulnerability mitigation efforts with the

CRO, creates a central repository for vulnerability information and

tracking, provides executive engagement and oversight of enterprise

vulnerabilities by the Executive Risk Steering Committee (ERSC),

promotes cross-functional collaboration across TSA offices, and requires

the collaboration of Assistant Administrators and their respective staff

across the Agency.

See figure 3 below for an overview of how TSA’s vulnerability

management process is intended to work. The CRO told us that

employees from all levels can report risks with broader, enterprise-level

application to the OCRO. Once the OCRO decides the risks are at an

enterprise level, the office assembles a working group and submits ideas

to the ERSC to decide at what level it should be addressed. The risk is

then assigned to an executive who will be required to provide a status

update.

Page 23 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Figure 3: Transportation Security Administration Vulnerability Management

Process

Fourth, officials in the TSA OCRO told us that TSA has established points

of contact in every program office, referred to as ERM Liaisons. Each

ERM Liaison is a senior level official that represents their program office

Page 24 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

in all ERM related activities. TSA also implemented risk management

awareness training to headquarters and field supervisors that covered

topics such as risk-based decision-making, risk assessment, and

situational awareness. Officials told us they are also embedding ERM

principles into existing training, so that employees will understand how

ERM fits into TSA operations.

Customizing ERM tools and templates can help ensure risk management

efforts fit agency culture and operations. For example, NIST tailored

certain elements of the Commerce ERM framework to better reflect the

bureau’s risk thresholds. Commerce has developed a set of standard risk

assessment criteria to help identify and rate risks, referred to as the

Commerce ERM Reference Card. NIST officials reported that some of the

safety and security terms used at Commerce differed from the terms used

at NIST and required tailoring to map to NIST’s existing safety risk

framework, which is a heavily embedded component of NIST operations

and culture. To better align to NIST, the NIST ERM Program split safety

and security risks into distinct categories when establishing a tailored

ERM framework for the bureau (see table 3).

According to agency officials, the NIST ERM Reference Card also

leverages American National Standards Institute guidelines, so it does not

introduce another separate and potentially conflicting set of terms.

Officials told us that these adaptations to the NIST ERM framework help

maintain continuity with the Commerce framework, but reflect the

particular mission, needs, and culture of NIST.

NIST Adapted the Commerce

ERM Framework to Reflect

Lab Safety Vocabulary

Appropriate to Its Culture

Page 25 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Table 3: Comparison of Department of Commerce (Commerce) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Reference Cards

Risk Level

(lowest to

highest)

Commerce

Safety & Security

(includes IT security)

NIST

Safety

(of Personnel, the

Environment and

Public Health)

NIST

Security

(includes Cyber,

Personnel and

Physical Security)

1

No harm

Near miss. Minimal treatment

required.

Minimal Impact. Easily contained asset damage,

loss or harm.

2

Minor first aid treatment or

minor loss of Commerce

asset

Minor first aid treatment or

routine clean-up

Limited loss of NIST asset or temporary disruption

to operations. Slight facility/property damage or

harm.

3

Medical treatment required or

moderate loss of Commerce

asset.

Medical treatment beyond first

aid required, lost work day(s).

More than routine clean-up.

Moderate loss of NIST asset or moderate impact

to operations. More than slight facility/property

damage or harm.

4

Serious injury or major loss of

Commerce asset

Serious injury, temporary

disability. Temporary

environmental or public health

impact.

Major loss of NIST asset, including subsystem

loss, inability to perform essential functions or

serious facility/property damage or harm.

5

Death or permanent injury or

complete loss of Commerce

asset

Death or permanent disability.

Lasting environmental or

public health impact.

Catastrophic; unrecoverable major system/facility

loss or harm. Inability to perform multiple essential

functions.

Source: Department of Commerce. | GAO-17-63

The following examples illustrate how selected agencies are integrating

ERM capability to support strategic planning and organizational

performance management. These include how they have:

• incorporated ERM into strategic planning processes, and

• used ERM to improve information for agency decisions.

This good practice most closely relates to Assess Risks, one of the

Essential Elements of Federal Government ERM, shown in table 1.

Through ERM, an agency looks for opportunities that may arise out of

specific situations, assesses their risk, and develops strategies to achieve

positive outcomes. In the federal environment, agencies can leverage the

GPRAMA performance planning and reporting framework to help better

manage risks and improve decision making. For example, Treasury has

integrated ERM into its existing strategic planning and management

processes. According to our review of the literature and the subject matter

specialists we interviewed, using existing processes helps to avoid

creating overlapping processes. Further, by incorporating ERM this way,

Good Practice: Integrate

ERM Capability to Support

Strategic Planning and

Organizational

Performance Management

Treasury Used Risk

Discussions in Quarterly

Performance Reviews

Page 26 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

risk management becomes an integral part of setting goals, including

agency priority goals (APG), ultimately achieving an organization’s

desired outcomes. Agencies can use regular performance reviews, such

as the quarterly performance reviews of APGs and annual leadership-

driven strategic objective review, to help increase attention on progress

towards the outcomes agencies are trying to achieve. According to OMB

Circular No. A-11, agencies are expected to manage risks and challenges

related to delivering the organization’s mission. The agency’s strategic

review is a process by which the agency should coordinate its analysis of

risk using ERM to make risk-aware decisions, including the development

of risk profiles as a component of the annual strategic review, identifying

risks arising from mission and mission-support operations, and providing

a thoughtful analysis of the risks an agency faces towards achieving its

strategic objectives. Instituting ERM can help agency leaders make risk-

aware decisions that affect prioritization, performance, and resource

allocation.

Treasury officials stated they integrated ERM into their quarterly

performance or data-driven reviews and strategic reviews, both of which

already existed. Officials stated this action has helped elevate and focus

risk discussions. Staff from the management office and individual bureaus

work together to complete the template slide, which is used to include a

risk element in their performance reviews. As part of this process, they

are assessing risk. See figure 4 for how risk is incorporated into

Treasury’s quarterly performance review (QPR) template. Officials stated

that they believe this approach to prepare for the data-driven review has

helped improve outcomes at Treasury. For example, according to agency

officials, Treasury used its QPR process to increase cybersecurity.

Treasury officials also told us that during the fall and the spring, each

Treasury bureau completes the data-driven review templates. Agency

officials are to use the summer data-driven review as an opportunity to

discuss budget formulation. In winter, they are to use the annual data-

driven review to show progress towards achieving strategic objectives.

21

According to agency officials, the strategic review examines and

assesses risks identified as part of the data-driven reviews and

aggregates and analyzes these results at the cross cutting strategic

21

OMB requires agencies to conduct leadership-driven, annual reviews of their progress

towards achieving each strategic objective—the outcome or impact the agency is

intending to achieve through its various programs and initiatives—established in their

strategic plans. These reviews are known as the strategic review.

Page 27 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

objective level, which helps improve agency performance. Integrating

ERM into this existing data-driven review process avoids creating a

duplicative process and increases the focus on risk.

Figure 4: Department of the Treasury Quarterly Performance Review Templates

In another example, Treasury officials identified implementation of the

Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014 (DATA Act) both at

Treasury and government-wide as a risk and established “Financial

Transparency” as one of its two APGs for fiscal years 2016 and 2017.

According to agency officials, incorporating risk management into the

data-driven review process sends a signal about the importance of the

DATA Act and brings additional leadership focus and scrutiny needed to

successfully implement the law.

Page 28 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

The literature we reviewed notes that ERM contributes to leaders’ ability

to identify risks and adjust organizational priorities to enhance decision-

making efforts. For example, OPM has a Risk Management Council

(RMC) that builds risk-review reporting and management strategies into

existing decision making and performance management structures. This

includes Performance Dashboards, APG reviews, and regular meetings

of the senior management team, as is recommended by the CFOC and

PIC Playbook. The RMC also uses an existing performance dashboard

for strategic goal reviews as part of its ERM process and to help inform

decisions as a result of these reviews. Officials told us they present their

dashboards every 6 or 7 weeks to the Chief Management Officer (CMO)

and RMC, as part of preparing for their data-driven reviews. Each project

and its risks are mapped against the strategic plan. When officials

responsible for a goal identify risks, they must also provide action plan

strategies, timelines, and milestones for mitigating risks.

Figure 5 shows an OPM dashboard to illustrate how OPM tracks progress

on a goal of preparing the federal workforce for retirement, for such a risk

as an unexpected retirement surge, and documents mitigation strategies

to address such events. According to agency officials, the CMO and RMC

monitor high level and high visibility risks on a weekly basis. In August

2016, OPM officials told us they were monitoring five to seven major

projects, such as information technology (IT) security implementation and

retirement services processes.

OPM Builds Agency View of

Risk into Decision Making and

Organizational Performance

Management Reviews

Page 29 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Figure 5: Example of an Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Dashboard for Preparing the Federal Workforce for

Retirement Goal

Page 30 GAO-17-63 Enterprise Risk Management

Each quarterly data-driven review includes an in-depth look into a specific

goal and the examination of risks as part of the review. Officials told us

that in the past 3 years, they have covered each of the strategic goals

using the dashboard. According to officials, during one of these reviews,

OPM identified a new risk related to having sufficient qualified contracting

staff to meet the goal of effective and efficient IT systems. Since OPM

considers contracting a significant component of that goal, they decided

to create the Office of Procurement Operations to help increase attention

to contracting staff. Using ERM, OPM officials told us they believe that

they could better prioritize funding requests across the agency, ultimately

balance limited resources, and make better informed decisions.

The following examples illustrate how selected agencies are establishing

a customized ERM program into existing agency processes. These

include how they have:

• designed an ERM program that allows for customized agency fit,

• developed a consistent, routinized ERM program, and

• used a maturity model approach to build an ERM program.

This good practice relates primarily to Identify Risk and Select Risk

Response, two of the Essential Elements of Federal Government ERM

shown in table 1.

Effective ERM implementation starts with agencies establishing a

customized ERM program that fits their specific organizational mission,

culture, operating environment, and business processes but also contains

the essential elements of an ERM framework. The CFOC and PIC

Playbook focuses on the importance of a customized ERM program to

meet agency needs. This involves taking into account policy concerns,

mission needs, stakeholder interests and priorities, agency culture, and