The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer

Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured amidst Changes to the

Affordable Care Act

Prepared by:

Rachel Gareld

Kendal Orgera

Kaiser Family Foundation

and

Anthony Damico

Consultant

January 2019

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2

How have health insurance coverage options and availability changed under the ACA? ........................... 3

ACA Coverage Provisions .................................................................................................................... 3

Changes to the ACA under the Trump Administration ........................................................................... 5

How many people are uninsured? ............................................................................................................ 7

Who remains uninsured after the ACA and why do they lack coverage? ................................................. 10

How does lack of insurance affect access to care? ................................................................................. 13

What are the financial implications of lacking insurance?........................................................................ 16

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 18

Endnotes ............................................................................................................................................... 20

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 1

Executive Summary

In the past, gaps in the public insurance system and lack of access to affordable private coverage left

millions without health insurance, and the number of uninsured Americans grew over time, particularly

during economic downturns. By 2013, the year before the major coverage provisions of the Affordable

Care Act (ACA) went into effect, more than 44 million nonelderly individuals lacked coverage.

1

Under the ACA, as of 2014, Medicaid coverage expanded to nearly all adults with incomes at or below

138% of poverty in states that have adopted the expansion, and tax credits are available for people with

incomes up to 400% of poverty who purchase coverage through a health insurance marketplace. Millions

of people enrolled in ACA coverage, and the uninsured rate dropped to a historic low by 2016. Coverage

gains were particularly large among low-income adults in states that expanded Medicaid.

Despite large gains in health coverage, some people continued to lack coverage, and the ACA remained

the subject of political debate. Attempts to repeal and replace the ACA stalled in summer 2017, but there

have been several changes to implementation of the ACA under the Trump Administration that affect

coverage. In 2017, the number of uninsured rose for the first time since implementation of the ACA to

27.4 million.

2

Those most at risk of being uninsured include low-income individuals, adults, and people of

color. The cost of coverage continues to be the most commonly cited barrier to coverage.

3

Health insurance makes a difference in whether and when people get necessary medical care, where

they get their care, and ultimately, how healthy they are. Uninsured people are far more likely than those

with insurance to postpone health care or forgo it altogether. The consequences can be severe,

particularly when preventable conditions or chronic diseases go undetected. While the safety net of public

hospitals, community clinics and health centers, and local providers provides a crucial health care source

for uninsured people, it does not close the access gap for the uninsured.

For many uninsured people, the costs of health insurance and medical care are weighed against equally

essential needs, like housing, food, and transportation to work, and many uninsured adults report

financial stress beyond health care.

4

When uninsured people use health care, they may be charged for

the full cost of that care (versus insurers, who negotiate discounts) and often face difficulty paying

medical bills. Providers absorb some of the cost of care for the uninsured, and while uncompensated care

funds cover some of those costs, these funds do not fully offset the cost of care for the uninsured.

Under current law, nearly half (45%) of the remaining uninsured are outside the reach of the ACA either

because their state did not expand Medicaid, they are subject to immigrant eligibility restrictions, or their

income makes them ineligible for financial assistance.

5

The remainder are eligible for assistance under

the law but may still struggle with affordability and knowledge of options. Ongoing efforts to further alter

the ACA or to make receipt of Medicaid more restrictive may further erode coverage gains seen under the

ACA. On the other hand, state action to take up the ACA Medicaid expansion could make more people

eligible for affordable coverage. The outcome of current debate over health coverage policy in the nation

and the states has substantial implications for people’s coverage, access, and overall health and well-

being.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 2

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) led to historic gains in health insurance coverage. The ACA builds on the

foundation of employer-based coverage and fills gaps in insurance availability and affordability by

expanding Medicaid for adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level ($16,753 per

year for an individual in 2018)

6

and providing premium tax credits to make private insurance in the

individual market more affordable for many with incomes between 100-400% of poverty (between

$12,140 and $48,560 per year for an individual in 2018). Most of the ACA’s major coverage provisions

went into effect in 2014, and millions of people have gained coverage under the law. Despite historic

coverage gains, millions of people continue to lack coverage, and the ACA remained the subject of

political debate. Under the Trump Administration, several changes to ACA implementation have altered

the availability of coverage or likelihood that people will sign up for coverage. In 2017, after years of

decreasing uninsured rates, the US saw coverage gains stall or reverse for some groups. Lack of

coverage reflects the fact that Medicaid eligibility for adults remains limited in states that have not

adopted the expansion, some people remain ineligible for financial assistance for private coverage, and

some still find coverage unaffordable even with financial assistance. Furthermore, ongoing efforts to alter

the ACA or limit Medicaid coverage for some groups may have caused confusion or fear among some

people and led them to drop or forgo coverage. These changes pose a challenge to further reducing the

number of uninsured and may further threaten coverage gains seen in recent years.

The gaps in our health insurance system affect people of all ages, races and ethnicities; however, those

with lower incomes face the greatest risk of being uninsured. Being uninsured affects people’s ability to

access needed medical care and their financial security. As a result, uninsured people are less likely to

receive preventive care and are more likely to be hospitalized for conditions that could have been

prevented.

7

The financial impact can also be severe. Uninsured families struggle financially to meet basic

needs, and medical bills can quickly lead to medical debt.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer provides information on how insurance has changed under the

ACA, how many people remain uninsured, who they are, and why they lack health coverage. It also

summarizes what we know about the impact that a lack of insurance can have on health outcomes and

personal finances and the difference health insurance can make in people’s lives.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 3

How have health insurance coverage options and

availability changed under the ACA?

In the past, gaps in the public insurance system and lack of access to affordable private coverage left

millions without health insurance. The ACA filled in many of these gaps and provided new coverage

options. Under the ACA, as of 2014, Medicaid coverage has been expanded to nearly all adults with

incomes at or below 138% of poverty in states that have adopted the expansion, and tax credits are

available for people with incomes up to 400% of poverty who purchase coverage through a health

insurance marketplace. These new coverage options have increased access to health insurance and

health care for millions, but recent actions may affect coverage options and people’s likelihood of signing

up for or retaining ACA coverage.

ACA Coverage Provisions

The ACA’s coverage provisions

built on and attempted to fill gaps

in a piecemeal insurance system

that historically left many without

affordable coverage. In the past,

many people did not have access to

affordable private coverage or were

ineligible for public coverage. Poor

and low-income adults were

particularly likely to lack coverage,

and the main reason that most people

said they lacked coverage was

inability to afford the cost.

8

The ACA

aimed to provide coverage options

across the income spectrum by filling

in gaps in eligibility for public coverage, access to employer coverage, and availability of affordable non-

group coverage (Figure 1).

9

The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility to low-income adults, eliminating categorical restrictions

on coverage in states that have expanded their programs. Medicaid and CHIP have long been

important sources of coverage for low-income children and people with disabilities, but in the past,

coverage for parents was limited to those with very low incomes (often below 50% of the poverty level),

and adults without dependent children—regardless of how poor—were ineligible.

10

The ACA expanded

Medicaid eligibility to nearly all adults with income at or below 138% of poverty. The 2012 Supreme Court

ruling effectively made the expansion a state option. As of January 2019, 37 states,

including DC, had

adopted Medicaid expansion under the ACA,

11

and over 12 million people were covered through the ACA

Medicaid expansion.

12

Figure 1

Major Sources of Health Insurance Coverage for the

Nonelderly Population under the Affordable Care Act

Traditional

Medicaid/CHIP

ACA Medicaid

Expansion

Employer-Sponsored

Insurance

ACA Marketplaces

Non-group Market

ACA

Market

Reforms

Higher

Income

Lower

Income

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 4

The ACA established health insurance marketplaces where individuals and small employers can

purchase non-group insurance, often with a subsidy. Very few people were covered by non-group

health insurance policies prior to the ACA, as such policies could be prohibitively expensive or

restrictive.

13

Under the ACA, health insurance marketplaces where individuals can shop for health

coverage operate in each state.

14

To make coverage purchased in these new marketplaces affordable,

the federal government provides tax credits for people with incomes between 100% and 400% of poverty.

Tax credits are available on a sliding scale based on income and limit premium costs to a share of

income. In addition, ACA allows for cost-sharing subsidies to reduce what people with incomes between

100% and 250% of poverty have to pay out-of-pocket to access health services. In 2018, more than 10

million people enrolled in marketplace plans, and the vast majority received financial assistance with their

coverage.

15

A small number of people still purchase non-group coverage outside the marketplace.

16

The ACA includes provisions to promote employer-based coverage. The availability and affordability

of employer-sponsored coverage has declined over time. From 2008 to 2013, the share of firms that

offered workers health benefits declined from 63% to 57%, and health insurance premium increases

outpaced growth in workers’ earnings and overall inflation.

17

Under the ACA, large and medium-size

employers (those with 50 or more full-time equivalent employees) are assessed a fee per full-time

employee (up to $2,320 in 2018) if they do not offer affordable coverage and have at least one employee

who receives a marketplace premium tax credit. To avoid penalties, employers must offer insurance that

pays for at least 60% of covered health care expenses, and the employee’s share of the individual

premium must not exceed a set share of family income (9.86% in 2019).

18

,

19

In addition, the ACA

established the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) marketplace to help small employers

and their workers access affordable health coverage.

20

Offer, eligibility, and take-up rates of employer-

sponsored insurance have largely stabilized since 2013,

21

and employer coverage remains the largest

source of health coverage for the nonelderly (covering 153 million people in 2017).

22

The ACA also extends dependent coverage in the private market. In the past, young adults (age 19-

26) were at particularly high risk of being uninsured, largely due to their low incomes and difficulty

affording coverage. As of 2010, young adults may remain on their parents’ private plans (including non-

group and employer-based plans) until age 26. This provision led to drastic decline in the young adult

uninsured rate from 32% in 2010 to 14% in 2017.

23

The ACA included nationwide insurance regulations to improve access to coverage for those who

may have been previously denied coverage and set new requirements for benefits and cost

sharing in ACA plans. Prior to the ACA, in many states, premiums in the non-group market could vary

by age or health status, and people with health problems or at risk for health problems could be charged

high rates, offered only limited coverage, or denied coverage altogether. The ACA included new rules for

insurers prevent them from denying coverage to people for any reason, including their health status, and

from charging people who are sick more (though insurers can, within limits, still charge older people more

for coverage). In addition, the ACA established a minimum “essential health benefits” package for

marketplace plans, Medicaid expansion enrollees, and some employer plans.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 5

Under the ACA, almost all people were required to have health insurance coverage or be subject

to a tax penalty. This requirement was intended to encourage healthier individuals to purchase coverage

through the marketplace. The requirement only applied to those with access to affordable coverage,

defined as costing no more than 8% of an individual’s or family’s income (certain other exemptions to the

mandate also were granted). The penalty from 2016 to 2018 was assessed as 2.5 percent of family

income, with both a minimum and maximum.

24

Coverage for immigrants remains limited under the ACA. Lawfully-present immigrants can receive

coverage through the ACA marketplaces, but they continue to face eligibility restrictions in Medicaid that

have been in place since prior to the ACA. Specifically, many lawfully present non-citizens who would

otherwise be eligible for Medicaid remain subject to a five-year waiting period before they may enroll.

25

Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid and are prohibited from purchasing coverage

through a marketplace or receiving tax credits.

Changes to the ACA under the Trump Administration

With the change in Administration in January 2017, there was renewed debate over the future of the ACA.

Discussion of ACA repeal and public comments from President Trump declaring the law to be “dead” and

“finished,”

26

led some people to be confused about whether the law remained in effect.

27

In addition,

reduced funding for outreach and enrollment assistance programs led to reduction in these services.

28

While attempts to repeal and replace the ACA stalled out in summer 2017, there have been several

changes to implementation of the ACA that affect coverage options and people’s likelihood of signing up

for or retaining ACA coverage.

In October 2017, the Trump Administration announced it would no longer make payments to

insurers for cost-sharing reductions (CSRs). Regardless of whether the federal government

reimburses insurers for CSR subsidies, insurers are still legally required under the ACA to offer reduced

cost-sharing via silver-level plans to eligible consumers. Many built the loss of CSR payments into their

premiums for silver plans for 2018 and again in 2019.

29

,

30

Because premium tax credits on the

exchanges are tied to the cost of silver premiums, the effect of the loss of CSR payments was cushioned

for many enrollees purchasing insurance through the ACA marketplace.

The individual mandate is no longer in effect as of 2019. As part of tax reform legislation passed in

December 2017, Congress reduced the individual mandate penalty to $0 effective in 2019. Repeal of the

individual mandate is expected to deter healthier people from enrolling in coverage and thus lead to a

sicker—and more expensive—risk pool in the marketplace. Analysis of insurer rate filings shows that

plans increased marketplace premiums to account for the loss of the individual mandate.

31

Because

customers receiving marketplace subsidies will continue to pay sliding-scale premiums based largely on

their incomes, these premium increases primarily affect unsubsidized customers and those purchasing

individual coverage outside the ACA marketplace. In December 2018, a federal judge in Texas ruled that

the change to the law’s individual mandate made the entire law itself unconstitutional, though that

decision has no effect as the case works its way through the appeals process.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 6

New, more loosely-regulated plans may now compete with ACA marketplace plans. In 2018, the

Trump administration announced new rules that will allow more loosely regulated plans – both short-term

limited duration (STLD) plans and association health plans (AHPs) – to proliferate on the individual

market in competition with ACA-compliant coverage.

32

These more loosely regulated plans will serve as a

more affordable option for some people who are not eligible for the ACA’s premium tax credits. However,

particularly in the case of short-term plans, this lower-cost coverage is generally unavailable to people

with pre-existing conditions, and the plans often exclude coverage for certain services.

33

These plans will

attract disproportionately healthy individuals away from ACA-compliant coverage, thus having an upward

effect on premiums in the ACA-compliant individual market.

In 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued new guidance regarding

Medicaid waivers and invited states to develop waivers, including some that restrict Medicaid

eligibility and enrollment.

34

Under the previous administration, CMS approved certain eligibility- and

enrollment-related waiver provisions as part of ACA Medicaid expansion waivers. Under the Trump

administration, states are seeking to apply these previously approved provisions as well as new

restrictions to both expansion and traditional Medicaid populations. The Trump administration also has

approved eligibility and enrollment restrictions that have never been approved before, such as

conditioning eligibility on meeting work requirements; coverage lock-outs for failure to report changes

affecting eligibility; and eliminating retroactive coverage for nearly all Medicaid enrollees, among others.

In some states, these provisions apply to both expansion adults and traditional Medicaid populations.

New public charge rules could have a chilling effect on coverage among immigrants. In October

2018, the Trump Administration published a proposed rule that would make changes to “public charge”

policies. Under longstanding policy, the federal government can deny an individual entry into the U.S. or

adjustment to legal permanent resident (LPR) status (i.e., a green card) if he or she is determined likely to

become a public charge. Under the proposed rule, officials would newly consider use of certain previously

excluded programs, including Medicaid, in public charge determinations. The changes would likely lead to

decreases in participation in Medicaid among legal immigrant families and their U.S.-born children

beyond those directly affected by the changes.

35

The effect of these policy changes on enrollment and coverage is currently playing out and will

continue to develop. After growing for the first few years of ACA implementation, marketplace

enrollment declined slightly in 2017 and 2018 then dropped substantially in 2019.

36

In the one state that

has implemented Medicaid work requirements to date, Arkansas, over 18,000 people lost Medicaid in

2018 for failing to meet work or reporting requirements;

37

it is unclear whether these people gained other

sources of coverage, but low offer rates of employer coverage among low-wage workers make it likely

that many did not.

38

In addition, recent research suggests that changes in immigration policy focused on

restricting immigration and enhancing immigration enforcement are causing some immigrant families to

turn away from public programs, including Medicaid and CHIP.

39

As additional data on health coverage

becomes available, it will be important to assess the effect of these changes, combined with other

economic trends, on health coverage.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 7

How many people are uninsured?

Before the ACA, the number of uninsured Americans grew over time, particularly during economic

downturns. By 2013, the year before the major coverage provisions of the ACA went into effect, more

than 44 million people lacked coverage.

40

Under the ACA, millions of people have gained health

coverage, and the uninsured rate dropped to a historic low in 2016. Coverage gains were particularly

large among low-income people living in states that expanded Medicaid. However, for the first time since

the implementation of the ACA, the number of people remaining without coverage increased by half a

million in 2017, reaching 27.4 million.

Under the ACA, the uninsured rate

and number of uninsured people

declined to a historic low by 2016.

The number of uninsured people and

the share of the nonelderly population

that was uninsured rose from 44.2

million (17.1%) to 46.5 million

(17.8%) between 2008 and 2010 as

the country faced an economic

recession (Figure 2). As early

provisions of the ACA went into effect

in 2010, and as the economy

improved, the number of uninsured

and uninsured rate began to drop,

hitting 44.4 million (16.8%) in 2013.

When the major ACA coverage provisions went into effect in 2014, the number of uninsured and

uninsured rate dropped dramatically and continued to fall through 2016 to 26.7 million (10.0%).

41

Overall,

nearly 20 million more people had coverage in 2016 than before the ACA was passed.

Coverage gains through 2016 were

largest among low-income people,

people of color, and adults—

groups that had high uninsured

rates prior to 2014—and were

particularly large in states that

expanded Medicaid. While

uninsured rates decreased across all

income groups from 2013 to 2016,

they declined most sharply for poor

and near-poor people, dropping by

9.7 percentage points and 11.4

percentage points, respectively

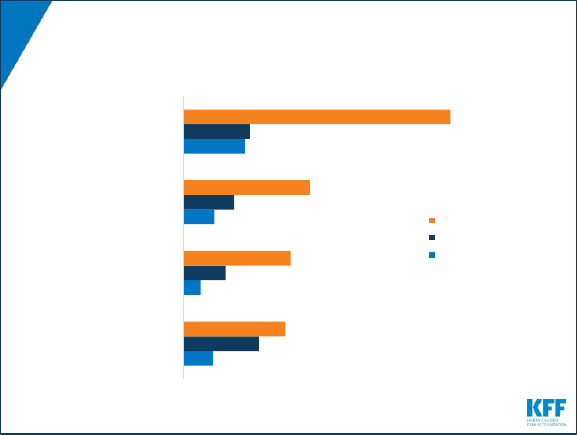

(Figure 3). Among racial and ethnic

Figure 3

-9.7%

-11.4%

-4.5%

-5.3%

-8.2%

-10.9%

-8.6%

-2.9%

-8.4%

-7.4%

-5.9%

Change in Uninsured Rate Among the Nonelderly

Population by Selected Characteristics, 2013-2016

NOTE: Includes nonelderly individuals ages 0 to 64. Asian includes Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPIs).

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2013 & 2016 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

Poverty Level

(% of FPL)

Race/Ethnicity Age Group

<100%

100-

199%

>200% White Black Hispanic Asian Children Adults Expanded

Did Not

Expand

State Medicaid

Expansion Status

Figure 2

44.2

45.0

46.5

45.7

44.8

44.4

35.9

29.1

26.7

27.4

17.1%

17.3%

17.8%

17.4%

17.0%

16.8%

13.5%

10.9%

10.0%

10.2%

-

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

25.0

30.0

35.0

40.0

45.0

50.0

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

Number of Uninsured and Uninsured Rate Among

the Nonelderly Population, 2008-2017

NOTE: Includes nonelderly individuals ages 0 to 64.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2008-2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 8

groups, Hispanics, Blacks, and Asians had particularly large declines in uninsured rates, with each group

seeing a drop of over 8 percentage points from 2013 to 2016 (Figure 3).

42

Because the expansions are

largely targeted to adults, who have historically had higher uninsured rates than children, nearly the entire

decline in the number of uninsured people under the ACA has occurred among adults. Uninsured rates

dropped nearly immediately in expansion states following implementation of the ACA’s coverage

provisions, declining by 7.4 percentage points from 2013 to 2016, with even larger declines among adults

(a 9.2 percentage point drop) widely attributed to gains in Medicaid coverage. Uninsured rates among the

nonelderly population also dropped in non-expansion states following ACA implementation (down 5.9

percentage points), in part as a result of the availability of ACA subsidies for private insurance to those

with incomes above poverty, increased participation among those eligible but not enrolled in Medicaid,

and increased outreach and enrollment efforts surrounding the ACA in all states.

43

In 2017, the uninsured rate

reversed course and, for the first

time since the passage of the ACA,

rose significantly to 10.2%. Groups

that saw significant increases in their

uninsured rate from 2016 to 2017

include Black, non-Hispanics,

children, older adults (age 45-64),

and middle-income families (above

twice the poverty level) (Appendix

Table 1). From 2016 to 2017,

changes in the uninsured rate in the

set of states that expanded Medicaid

were essentially flat overall, declining

by less than 0.1 percentage points,

but patterns varied by states and by demographic group (Figure 4). In contrast, the uninsured rate in

states that did not expand Medicaid increased both overall (rising by 0.6 percentage points) and for most

groups. As with expansion states, changes in coverage from 2016-2017 varied within the set of states

that have not expanded Medicaid.

Figure 4

<0.01%

0.1%

-0.1%*

-0.5%

-0.2%*

0.1%

-0.1%

-0.2%

-0.2%*

0.1%

0.6%*

0.5%*

0.9%

0.1%

0.5%*

0.5%*

0.5%

0.4%*

0.7%*

0.7%*

Total

White

Black

Hispanic

Other race/ethnicity

Children (0-18)

Nonelderly Adults (19-64)

<100% FPL

100%-199% FPL

≥200% FPL

Expansion States

Non-Expansion

States

Change in Uninsured Rate Among the Nonelderly Population

by Selected Characteristics and Expansion Status, 2016-2017

NOTE: * Indicates a statically significant change between 2016 and 2017. Includes nonelderly individuals ages 0 to 64.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2016 & 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

Race/

Ethnicity

Age

Poverty

Level

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 9

Many remain uninsured are eligible

for ACA assistance, but about half

are outside the reach of the ACA.

Of the remaining uninsured in 2017,

more than half (15.0 million, or 55%)

are eligible for financial assistance

through either Medicaid or subsidized

marketplace coverage. However,

nearly half of uninsured people

remain outside the reach of the ACA.

Some (4.1 million, or 15%) are

ineligible due to their immigration

status or their state’s decision not to

expand Medicaid. The remainder of

the uninsured either has an offer of

coverage through an employer or has income above the limit for marketplace tax credits (Figure 5). These

patterns of eligibility vary by state.

44

In the fourteen states that had not expanded Medicaid as of January 2019, 2.5 million poor adults

fall into a “coverage gap.”

45

These adults have incomes above Medicaid eligibility limits in their state

but below the lower limit for marketplace premium tax credits, which begin at 100% of poverty. In non-

expansion states, the median income eligibility level for parents is 43% of poverty and 0% for childless

adults.

46

People in the coverage gap are concentrated in Southern states, with the largest number of

people in the coverage gap in Texas (759,000 people, or 31%) followed by Florida (445,000, or 18%),

Georgia (267,000, or 11%), and North Carolina (215,000, or 9%).

47

Figure 5

Medicaid/

Other Public

Eligible Adult

4.4 M

Medicaid/

Other Public

Eligible Child

2.4 M

Tax Credit

Eligible

8.2 M

In the

Coverage

Gap

2.5 M

Ineligible for

Coverage Due to

Immigration

Status

4.1 M

Ineligible for

Financial

Assistance Due

to ESI Offer

3.8 M

Ineligible for Financial

Assistance Due to Income

1.9 M

Eligibility for ACA Coverage Among Nonelderly

Uninsured, 2017

NOTES: Numbers may not sum to totals due to rounding. Tax Credit Eligible share includes adults in MN and NY who are eligible

for coverage through the Basic Health Plan. Medicaid/Other Public also includes CHIP and some state-funded programs for

immigrants otherwise ineligible for Medicaid.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

Eligible for

Financial

Assistance

55%

Total = 27.4 Million Nonelderly Uninsured

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 10

Who remains uninsured after the ACA and why do they

lack coverage?

Despite coverage gains, groups with historically high uninsured rates continue to be at highest risk of

being uninsured, including low-income individuals, adults, and people of color. Although most remaining

uninsured people are in working families, cost continues to pose a major barrier to coverage with nearly

half (45%) of uninsured nonelderly adults in 2017 saying that they lacked coverage because it was too

expensive.

48

Though provisions in the ACA aim

to make coverage more affordable

for low and moderate-income

families, these income groups still

make up the vast majority of the

uninsured. Low-income individuals

are at the highest risk of being

uninsured.

49

Nearly half of the

remaining uninsured population

(47%) has family income below 200%

of poverty ($19,730 for a family with

two adults and one child in 2017)

50

and another 35% has family income

between 200 and 399% of poverty

(Figure 6).

A majority of the remaining uninsured population is in a family with at least one worker, and many

uninsured workers continue to lack access to coverage through their job. Not all workers have

access to health coverage through their jobs or can afford the coverage offered to them. In 2017, more

than three-quarters (77%) of the uninsured had at least one full-time worker in their family, and an

additional 10% had a part-time worker in their family (Figure 6).

51

As in the past, low-income workers and

those who work in agriculture, construction, and service jobs are more likely than other workers to be

uninsured.

52

Moreover, not all workers have access to health coverage through their job. In 2017, 71% of

nonelderly uninsured workers worked for an employer that did not offer health benefits to the worker.

53

People of color are at higher risk of being uninsured than Whites. While a plurality (41%) of the

uninsured are non-Hispanic Whites, people of color are disproportionately likely to be uninsured: they

make up 42% of the overall nonelderly U.S. population but account for over half of the total nonelderly

uninsured population (Figure 6). Hispanics and Blacks have significantly higher nonelderly uninsured

rates (18.9% and 11.1%, respectively) than Whites (7.3%).

54

Differences in coverage by race/ethnicity

likely reflect a combination of factors, including language and immigration barriers, income and work

status, and state of residence.

Figure 6

White

41%

Black

14%

Hispanic

37%

Asian/

NHOPI

4%

AIAN

2%

Other

2%

Race

Characteristics of the Nonelderly Uninsured, 2017

NOTE: Includes nonelderly individuals ages 0 to 64. The US Census Bureau’s poverty threshold for a family with two adults and

one child was $19,730 in 2017. Data may not sum to 100% due to rounding. NHOPI refers to Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific

Islanders. AIAN refers to American Indians and Alaska Natives. Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race; all other

race/ethnicity groups are non-Hispanic.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

<100%

FPL

18%

100-199%

FPL

29%

200-399%

FPL

35%

400%+

FPL

18%

Family Income

(%FPL)

1 or

More

Full-

Time

Worke

rs

77%

Part-Time

Workers

10%

No

Workers

13%

Family Work Status

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 11

Adults are still more likely than children to be uninsured. Nonelderly adults were more than twice as

likely as children (12% vs. 5%) to be uninsured in 2017.

55

This disparity reflects ongoing differences in

eligibility for public coverage. While the ACA has increased Medicaid eligibility levels for adults, states

have expanded coverage for children even higher through CHIP, while adults without children are

excluded from Medicaid in all but one non-expansion state.

56

Uninsured rates for children are low, and most uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid or

CHIP. Largely due to expanded eligibility for public coverage under Medicaid and CHIP, the uninsured

rate for children is relatively low: in 2017, 5% of children nationwide were uninsured.

57

Over three in five

(64%) uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid, CHIP, or other public programs.

58

Some of these

children may be reached by covering their parents, as research has found that parent coverage in public

programs is associated with higher enrollment of eligible children.

59

,

60

Insurance coverage continues to

vary by state and region, with

individuals living in non-expansion

states being most likely to be

uninsured (Figure 7). In 2017,

thirteen out of the eighteen states

with the highest uninsured rates were

non-expansion states.

61

Economic

conditions, availability of employer-

sponsored coverage, and

demographics are other factors

contributing to variation in uninsured

rates across states.

While most of the uninsured are U.S. citizens, non-citizens continue to be at much higher risk of

being uninsured. In 2017, three out of four (75%) uninsured nonelderly individuals were citizens.

However, non-citizens (including those who are lawfully present and those who are undocumented) are

more likely than citizens to be uninsured in 2017. Among citizens, 8% were uninsured in 2017, compared

to 33% of non-citizens.

62

Cost still poses a major barrier to coverage for the uninsured. Nearly half (45%) of uninsured adults

in 2017 said that they lacked coverage was because of high cost.

63

Though financial assistance is

available to many of the remaining uninsured under the ACA,

64

not everyone who is uninsured is eligible

for free or subsidized coverage. In addition, some uninsured who are eligible for help may not be aware of

coverage options or may face barriers to enrollment.

65

Outreach and enrollment assistance was key to

facilitating both initial and ongoing enrollment in ACA coverage, but these programs face challenges due

to funding cuts and high demand.

66

,

67

Figure 7

Uninsured Rate Among the Nonelderly by State,

2017

NOTE: Includes nonelderly individuals ages 0 to 64.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

HI

AK

WA

OR

WY

UT

TX

SD

OK

ND

NM

NV

NE

MT

LA

KS

ID

CO

CA

AR

AZ

WI

WV

VA

TN

SC

OH

NC

MO

MS

MN

MI

KY

IA

IN

IL

GA

FL

AL

VT

PA

NY

NJ

NH

MA

ME

DC

CT

DE

RI

MD

<7% (9 States + DC)

7%-10% (23 States)

>10% (18 States)

United States: 10.2%

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 12

Access to health coverage changes as a person’s situation changes. In 2017, 22% of uninsured

nonelderly adults said they were uninsured because the person who carried the health coverage in their

family lost their job or changed employers.

68

More than one in ten were uninsured because of a marital

status change, the death of a spouse or parent, or loss of eligibility due to age or leaving school (11%),

and some lost Medicaid because of a new job/increase in income or the plan stopping after pregnancy

(11%).

69

Most people who remained uninsured nonelderly adults in 2017 were uninsured for more than a

year. Though the share of uninsured who lacked coverage for more than a year decreased from 81% in

2013 to 74% in 2017,

70

the vast majority of uninsured people were still long-term uninsured.

People who

have been without coverage for long periods may be particularly hard to reach through outreach and

enrollment efforts.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 13

How does lack of insurance affect access to care?

Health insurance makes a difference in whether and when people get necessary medical care, where

they get their care, and ultimately, how healthy they are. Uninsured people are far more likely than those

with insurance to postpone health care or forgo it altogether. The consequences can be severe,

particularly when preventable conditions or chronic diseases go undetected.

Compared to those who have health coverage, people without health insurance are more likely to

skip preventive services and report that they do not have a regular source of health care. Adults

who are uninsured are over three times more likely than insured adults to say they have not had a visit

about their own health to a doctor or

other health professional’s office or

clinic in the past 12 months.

71

They

are also less likely to receive

recommended screening tests such

as blood pressure checks, cholesterol

checks, blood sugar screening, pap

smear or mammogram (among

women), and colon cancer

screening.

72

Part of the reason for

poor access among the uninsured is

that half do not have a regular place

to go when they are sick or need

medical advice, while the majority of

insured people do have a regular

source of care (Figure 8).

73

Uninsured people are more likely than those with insurance to report problems getting needed

medical care. One in five (20%) uninsured adults say that they went without needed care in the past year

because of cost compared to 3% of adults with private coverage and 8% of adults with public coverage.

74

Many uninsured people do not obtain the treatments their health care providers recommend for them. In

2017, 19% of uninsured adults said they delayed or did not get a needed prescription drug due to cost,

compared to 14% with public coverage and 6% with private coverage.

75

And while insured and uninsured

people who are injured or newly diagnosed with a chronic condition receive similar plans for follow-up

care from their doctors, people without health coverage are less likely than those with coverage to obtain

all the recommended services.

76

,

77

Because uninsured people are less likely than those with insurance to have regular outpatient

care, they are more likely to have negative health consequences. Because uninsured patients are

also less likely to receive necessary follow-up screenings than their insured counterparts,

78

they have an

increased risk of being diagnosed at later stages of diseases, including cancer, and have higher mortality

rates than those with insurance.

79

,

80

,

81

In addition, when uninsured people are hospitalized, they receive

Figure 8

6%

3%

6%

11%

14%

8%

9%

12%

19%

20%

24%

50%

Postponed or did not

get needed prescription

drug due to cost

Went without needed

care due to cost

Postponed seeking care

due to cost

No usual source of care

Uninsured

Medicaid/Other Public

Employer/Other Private

Barriers to Health Care Among Nonelderly Adults by

Insurance Status, 2017

NOTE: Includes nonelderly individuals ages 18 to 64. Includes barriers experienced in past 12 months. Respondents who said

usual source of care was the emergency room were included among those not having a usual source of care. All differences

between uninsured and insurance groups are statistically significant (p<0.05).

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 National Health Interview Survey.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 14

fewer diagnostic and therapeutic services and also have higher mortality rates than those with

insurance.

82

,

83

,

84

,

85

Uninsured children also face

problems getting needed care.

Uninsured children are more likely to

lack a usual source of care, to delay

care, or to have unmet medical needs

than children with insurance (Figure

9).

86

Further, uninsured children with

common childhood illnesses and

injuries do not receive the same level

of care as others and are at higher

risk for preventable hospitalizations

and for missed diagnoses of serious

health conditions.

87

,

88

Among children

with special health care needs, those

without health insurance have worse

access to care than those with

insurance.

89

Lack of health coverage, even for short periods of time, results in decreased access to care.

Research has shown that adults who experience gaps in their health insurance coverage are less likely to

have a regular source of care or to be up to date with blood pressure or cholesterol checks than those

with continuous coverage.

90

Research also indicates that children who are uninsured for part of the year

have more access problems than those with full-year coverage.

91

,

92

Similarly, adults who lack insurance

for an entire year have poorer access to care than those who have coverage for at least part of the

year, suggesting that even a short period of coverage can improve access to care.

93

Research demonstrates that gaining health insurance improves access to health care

considerably and diminishes the adverse effects of having been uninsured. A seminal study of a

Medicaid expansion in Oregon found that uninsured adults who gained Medicaid coverage were more

likely to have an outpatient visit or receive a prescription and less likely to have depression or stress in

the short term than their counterparts who did not gain coverage.

94

Findings two years out from the

expansion showed significant improvements in access, utilization, and self-reported health among the

adults who gained coverage.

95

In addition, a large body of research on the impact of Medicaid expansion

under the ACA demonstrates that gains in Medicaid coverage positively impact access to care and

utilization of health care services.

96

Research also shows that individuals who gained marketplace

coverage in 2014 were far more likely than those who remained uninsured to obtain a usual source of

care and receive preventive care services.

97

Public hospitals, community clinics and health centers provide a crucial health care safety net for

uninsured people; however, the safety net does not close the access gap for the uninsured. Safety

Figure 9

27%

15%

9%

13%

22%

25%

4%

2%

1%

3%

5%

15%

2%

1%

1%

2%

3%

12%

No Usual

Source of Care

Postponed

Seeking Care

Due to Cost

Went Without

Needed Care

Due to Cost

Last MD

Contact

>2 Years Ago

Unmet Dental

Need Due

to Cost

Last Dental Visit

>2 Years Ago

Uninsured Medicaid/Other Public Employer/Other Private

Children’s Access to Care by Health Insurance

Status, 2017

NOTE: Includes children ages 0 to 18. Includes barriers experienced in past 12 months. Respondents who said usual source of

care was the emergency room were included among those not having a usual source of care. All differences between uninsured

and insurance groups are statistically significant (p<0.05).

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 National Health Interview Survey.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 15

net providers, including public and community hospitals, community health centers, rural health centers,

and local health departments, provide care to many people without health coverage. In addition, nearly all

other hospitals and some private physicians provide some charity care. However, safety net providers

have limited resources and service capacity, and not all uninsured people have geographic access to a

safety net provider.

98

,

99

The ACA has led to significant growth in the number of health centers and their

service capacity through both new grant funds and new patient revenues due to expanded coverage.

100

However, this impact has been more limited in states not expanding Medicaid, where a much larger share

of health center patients remains uninsured than in states that did expand.

101

In addition, health centers in

all states report that securing needed specialty care for their uninsured patients is a major challenge.

102

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 16

What are the financial implications of lacking insurance?

For many uninsured people, the costs of health insurance and medical care are weighed against equally

essential needs, like housing, food, and transportation to work, and many uninsured adults report being

very or moderately worried about paying basic monthly expenses such as rent or other housing costs and

monthly bills.

103

When uninsured people use health care, they may be charged for the full cost of that care

(versus insurers, who negotiate discounts) and often face difficulty paying medical bills. Providers absorb

some of the cost of care for the uninsured, and while uncompensated care funds cover some of those

costs, these funds do not fully offset the cost of care for the uninsured.

Most uninsured people do not receive health services for free or at reduced charge. Hospitals

frequently charge uninsured patients two to four times what health insurers and public programs actually

pay for hospital services.

104

,

105

In 2015, only 27% of uninsured adults reported receiving free or reduced

cost care.

106

Uninsured people often must pay "up front" before services will be rendered. When people without

health coverage are unable to pay the full medical bill in cash at the time of service, they can sometimes

negotiate a payment schedule with a provider, pay with credit cards (typically with high interest rates), or

be turned away.

107

,

108

Among uninsured adults in 2015, a third (33%) were asked to pay for the full cost of

medical care before they could see a doctor.

109

People without health insurance have lower medical expenditures than those with insurance, but

they pay a much larger portion of their medical costs out-of-pocket. Nonelderly people without

health coverage had an average of $1,719 in health spending in 2016, less than half of average annual

spending for people with any private coverage ($4,846) and less than a third of average annual spending

for people with only public coverage ($6,421).

110

Despite lower overall medical spending, people without

insurance who use services pay a greater percentage of their expenses out-of-pocket than those with

insurance. As a result, in 2014, those without insurance who used medical services paid an average of

$752 out of pocket, compared to $658 for those with any private coverage and just $236 for those with

public coverage.

111

Providers incur billions in the cost of uncompensated care for the uninsured, not all of which is

offset by funding to defray these costs. In 2013, before the ACA was fully implemented, the

uncompensated costs of care for the uninsured amounted to about $85 billion, and funding from a

number of sources helped providers defray these costs. Most of these funds came from the federal

government through a variety of programs including Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share

hospital (DSH) payments, the Veterans Health Administration, the Indian Health Service, the Community

Health Centers block grant, and the Ryan White CARE Act, though states and localities provided billions

and the private sector provided a small share. Given the high cost of hospital-based care, the majority of

the cost of uncompensated care is incurred in hospitals. While substantial, these payments to providers

for uncompensated care amount to a small slice of total health care spending in the U.S.

112

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 17

With the expansion of coverage under the ACA, providers in states that expanded Medicaid are

seeing reductions in uncompensated care costs. For example, between 2013 and 2015, total

uncompensated care costs for hospitals (including charity care costs and bad debt) dropped from $37.3

billion to $28.7 billion, a $8.6 billion or 23% drop.

113

States that expanded Medicaid saw greater declines

in uncompensated care than states that have not expanded.

114

Anticipating fewer uninsured and lower

levels of uncompensated care, the ACA called for a reduction in federal Medicaid DSH payments; these

cuts have been postponed and are now scheduled to begin in 2020.

115

Being uninsured leaves individuals

at an increased risk of financial

strain due to medical bills. In 2017,

nonelderly uninsured adults were

over twice as likely as those with

insurance to have problems paying

medical bills (29% vs. 14%; Figure

10) with nearly two thirds of

uninsured who had medical bill

problems unable to pay their medical

bills at all (65%).

116

Uninsured adults

are also more likely to face negative

consequences due to medical bills,

such as using up savings, having

difficulty paying for necessities,

borrowing money, or having medical

bills sent to collection.

117

Most uninsured people have few, if any, savings or assets they can easily use to pay health care

costs. Uninsured people typically have limited access to funds to finance care. Only 40 and 50 percent of

single- and multi-person households with an uninsured person, respectively, had liquid assets in excess

of $1,000 in 2016, and less than a fifth (18 percent) in both household types had liquid assets above

$5,000.

118

Uninsured nonelderly adults are over twice as likely as insured adults to worry about being able

to pay costs for normal health care (61% vs. 27%; Figure 10). Furthermore, over three quarters of

uninsured nonelderly adults (76%) say they are very or somewhat worried about paying medical bills if

they get sick or have an accident, compared to 45% of insured adults.

119

Uninsured people are at risk of medical debt. Like any bill, when medical bills are not paid or are paid

off too slowly, they are turned over to a collection agency. Nearly three in five consumers (59%) reported

being contacted regarding a collection for medical bills in the United States.

120

In 2017, uninsured adults

were more likely than insured adults to say they have medical bills that are being paid off over time (31%

vs. 24%).

121

More than half (53%) of uninsured people said they had problems paying household medical

bills in the past year.

122

Figure 10

29%

61%

76%

31%

14%

27%

45%

24%

Problems paying or

unable to pay

medical bills

Worried about being

able to pay costs

for normal care

Worried about paying

medical bills if

get sick

Medical bills being

paid off over time

Uninsured Insured

Problems Paying Medical Bills by Insurance Status,

2017

NOTE: Includes nonelderly individuals ages 18 to 64. All differences between uninsured and insured groups are statistically

significant (p<0.05).

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 National Health Interview Survey.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 18

Conclusion

The ACA led to historic drops in the uninsured rate, with millions of previously uninsured Americans

gaining insurance and access to health services and protection from catastrophic health costs. Prior to

the ACA, the options for the uninsured population were limited in the individual market, as coverage was

often expensive and insurers could deny coverage based on health status. Medicaid and CHIP have

provided coverage to many families, but pre-2014 eligibility levels were low for parents and few states

provided coverage to adults without dependent children. The ACA filled in many of these gaps by

expanding Medicaid to low-income adults and providing subsidized coverage to people with incomes from

100 to 400% of poverty in the marketplaces.

Nonetheless, even with the ACA, the nation’s system of health insurance continues to have many gaps

that currently leave millions of people without coverage, and recent actions to alter the ACA under the

Trump Administration may limit availability of coverage. For the first time since passage of the law, the

number of uninsured people increased in 2017, and 27.4 million remain uninsured. Nearly half (45%) of

the remaining uninsured are outside the reach of the ACA either because their state did not expand

Medicaid, they are subject to immigrant eligibility restrictions, or their income makes them ineligible for

financial assistance. The remainder are eligible for assistance under the law but may still struggle with

affordability and knowledge of options and require targeted outreach to help them gain coverage. Going

without coverage can have serious health consequences for the uninsured because they receive less

preventive care, and delayed care often results in serious illness or other health problems. Being

uninsured can also have serious financial consequences, with many unable to pay their medical bills,

resulting in medical debt.

Ongoing debate about altering the ACA or limiting Medicaid to populations traditionally served by the

program could lead to further loss of coverage and place more people in jeopardy of facing access

barriers or financial strain due to being uninsured. On the other hand, if additional states opt to expand

Medicaid as allowed under the ACA, there may be additional coverage gains as low-income individuals

gain access to affordable coverage. The outcome of current debate over health coverage policy in the

nation and the states has substantial implications for people’s coverage, access, and overall health and

well-being.

Rachel Garfield and Kendal Orgera are with the Kaiser Family Foundation. Anthony Damico is an

independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 19

Appendix Table 1: Uninsured Rate Among the Nonelderly, 2013-2017

2013

Uninsured

Rate

2016

Uninsured

Rate

2017

Uninsured

Rate

Change in

Uninsured

Rate

2013-2017

Change in

Uninsured

Rate

2016-2017

Total - Nonelderly

a

16.8%

10.0%

10.2%

-6.6%

*

0.2%

*

Age

Children - Total

7.5%

4.7%

5.0%

-2.6%

*

0.3%

*

Adults - Total

20.6%

12.1%

12.3%

-8.2%

*

0.2%

*

Adults 19-25

26.8%

14.6%

14.8%

-11.9%

*

0.2%

Adults 26-34

26.3%

15.6%

15.6%

-10.7%

*

0.0%

Adults 35-44

21.2%

13.6%

13.6%

-7.6%

*

0.0%

Adults 45-54

17.4%

10.4%

10.7%

-6.7%

*

0.3%

*

Adults 55-64

13.4%

7.5%

7.9%

-5.5%

*

0.4%

*

Annual Family Income

<$20,000

28.0%

17.1%

17.2%

-10.8%

*

0.0%

$20,000 - $39,999

27.4%

16.8%

17.3%

-10.1%

*

0.5%

*

$40,000 +

11.4%

7.1%

7.5%

-3.9%

*

0.4%

*

Family Poverty Level

b

<100%

26.2%

16.5%

16.6%

-9.6%

*

0.1%

100-199%

28.4%

17.0%

17.2%

-11.2%

*

0.3%

200-399%

17.7%

11.3%

11.7%

-5.9%

*

0.4%

*

400%+

6.8%

4.1%

4.5%

-2.3%

*

0.3%

*

Household Type

1 Parent with children

c

11.5%

6.8%

7.1%

-4.4%

*

0.3%

2 Parents with children

c

10.8%

6.9%

7.2%

-3.6%

*

0.3%

*

Multigenerational

d

20.5%

11.8%

11.6%

-8.9%

*

-0.2%

Adults living alone or with other adults

20.1%

11.6%

11.8%

-8.3%

*

0.3%

*

Other

22.5%

13.5%

13.6%

-8.8%

*

0.1%

Family Work Status

2+ Full-time

13.4%

8.2%

8.5%

-5.0%

*

0.3%

*

1 Full-time

16.5%

10.2%

10.4%

-6.1%

*

0.2%

*

Only Part-time

e

26.2%

14.4%

14.6%

-11.6%

*

0.2%

Non-Workers

21.2%

12.7%

13.0%

-8.2%

*

0.3%

*

Race/Ethnicity

White only (non-Hispanic)

12.3%

7.1%

7.3%

-5.0%

*

0.3%

*

Black only (non-Hispanic)

18.8%

10.7%

11.1%

-7.7%

*

0.5%

*

Hispanic

30.0%

19.1%

18.9%

-11.1%

*

-0.2%

Asian/Native Hawaiian and Pacific

Islander

15.8%

7.2%

7.2%

-8.6%

*

0.0%

Am. Indian/Alaska Native

30.4%

22.0%

22.0%

-8.4%

*

0.1%

Two or more races

f

13.5%

7.7%

7.9%

-5.6%

*

0.2%

Citizenship

U.S. citizen - native

13.8%

7.9%

8.2%

-5.6%

*

0.3%

*

U.S. citizen - naturalized

20.3%

9.8%

10.0%

-10.3%

*

0.2%

Non-U.S. citizen, resident for < 5 years

38.5%

26.4%

27.2%

-11.3%

*

0.8%

Non-U.S. citizen, resident for 5+ years

51.4%

37.0%

36.0%

-15.4%

*

-1.0%

*

* Indicates a statistically significant difference from 2017 at the p < 0.05 level.

a

Nonelderly includes all individuals under age 65.

b

The U.S. Census Bureau’s poverty threshold for a family with two adults and one child was $19,730 in 2017.

c

Parent includes any

person with a dependent child.

d

Multigenerational families with children include families with at least three generations in a

household. Other families include those with adults are caring for children other than their own (e.g., a niece living with her aunt).

e

Part-time workers are defined as working < 35 hours per week.

f

Respondents can identify as more than one racial or ethnic group.

The hierarchy we use for determining racial/ethnic categories places all respondents who self-identify as mixed race who do not also

identify as Hispanic into the “Two or More Races” category. All individuals who identify with Hispanic ethnicity fall into the Hispanic

category regardless of selected race.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2013-2017 American Community Survey (ACS).

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 20

Endnotes

1

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2013 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

2

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

3

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 National Health Interview Survey.

4

Ibid.

5

Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Distribution of Eligibility for ACA Health Coverage Among those

Remaining Uninsured as of 2017,” accessed January 2019, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-

indicator/distribution-of-eligibility-for-aca-coverage-among-the-remaining-uninsured/.

6

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation,

2018 Poverty Guidelines. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

7

Samuel L Dickman, David Himmelstein, and Steffie Woolhandler, Inequality and the health-care system in the USA

(London, England: The Lancet, April 8, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7.

8

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, 2014.

9

Jennifer Tolbert, The Coverage Provisions in the Affordable Care Act: An Update (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family

Foundation, March 2015), https://www.kff.org/report-section/the-coverage-provisions-in-the-affordable-care-act-an-

update-health-insurance-market-reforms/.

10

Tricia Brooks, Karina Wagnerman, Samantha Artiga, and Elizabeth Cornachione, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility,

Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2018: Findings from a 50-State Survey (Washington,

DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-

enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2018-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/.

11

Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision,”

accessed January 2019, http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-

the-affordable-care-act/.

12

Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Medicaid Expansion Enrollment,” accessed January 2019,

https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-expansion-enrollment/.

13

Linda J Blumberg, John Holahan, and Erik Wengle, Are Nongroup Marketplace Premiums Really High? Not in

Comparison with Employer Insurance, (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, February 2017),

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/are-nongroup-marketplace-premiums-really-high-not-comparison-

employer-insurance.

14

Some states run their own marketplace, and other state marketplaces are run by the federal government. Kaiser

Family Foundation State Health Facts, “State Health Insurance Marketplace Types, 2018,” accessed January 2019,

http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-health-insurance-marketplace-types/.

15

Kaiser Family Foundation, Web Briefing for Journalists: Key Issues Ahead of Marketplace Open Enrollment,

October 2018, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/event/web-briefing-for-journalists-key-issues-ahead-of-marketplace-

open-enrollment/

16

Ibid.

17

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation,

October 2018), https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

18

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Form Rev. Proc. 2017-36, (Washington, DC: 2017),

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-17-36.pdf.

19

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Form Rev. Proc. 2018-34, (Washington, DC: 2018),

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-18-34.pdf.

20

Under the SHOP, employers with no more than 50 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees can purchase coverage

and employers with no more than 25 FTE employees and annual wages below a limit ($53,000 for tax year 2017)

may be eligible for tax credits for up to two years to reduce the cost of SHOP coverage. Beginning in January 2016,

states had the option to expand the SHOP to include employers with 100 or fewer FTEs. For tax years beginning in

2014 or later, employers could receive a tax credit of up to 50% of the employer’s contribution to the premium,

calculated on a sliding scale basis tied to average wages and number of employees. For small businesses with tax-

exempt status meeting the requirements above, the tax credit is 35% of the employer contribution. In order to qualify,

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 21

a business must pay premiums on behalf of employees enrolled in a qualified health plan offered through the SHOP

marketplace or qualify for an exemption to this requirement. “Small Business Health Care Tax Credit and the SHOP

Marketplace,” Internal Revenue Service, accessed December 2018, https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-

act/employers/small-business-health-care-tax-credit-and-the-shop-marketplace. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services, Health Insurance Marketplace, Who Can Use the SHOP Marketplace (Baltimore, MD: CMS, Health

Insurance Marketplace, October 2014), https://marketplace.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/who-can-use-shop.pdf

21

Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation,

October 2018), https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-summary-of-findings/.

22

Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Health Insurance Coverage of Nonelderly 0-64,” accessed January

2019, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/nonelderly-0-64/.

23

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2010 and 2017 National Health Interview Survey.

24

“Individual Share Responsibility Provision – Reporting and Calculating the Payment.” ACA Individual Shared

Responsibility Provision Calculating the Payment | Internal Revenue Service. February 2018.

https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/individuals-and-families/aca-individual-shared-responsibility-provision-

calculating-the-payment.

25

Lawfully present immigrants who would be eligible for Medicaid but are in a five-year waiting period are eligible for

tax credits for marketplace coverage. Samantha Artiga and Anthony Damico, Health Coverage and Care for

Immigrants (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, July 2017), http://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-

brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-immigrants/.

26

R. Savransky, The Hill, Trump: There is no such thing as Obamacare anymore, October 2017,

http://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/355658-trump-there-is-no-such-thing-as-obamacare-anymore.

27

Ashley Kirzinger, Liz Hamel, Biana DiJulio, Cailey Muñana, and Mollyann Brodie. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll –

November 2017: The Politics of Health Insurance Coverage, ACA Open Enrollment, (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser

Family Foundation, November 2017), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-

november-2017-the-politics-of-health-insurance-coverage-aca-open-enrollment/.

28

Karen Pollitz, Jennifer Tolbert, and Maria Diaz. Data Note: Changes in 2017 Federal Navigator Funding,

(Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2017), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/data-note-

changes-in-2017-federal-navigator-funding/.

29

Rabah Kamal, Ashley Semanskee, Michelle Long, Gary Claxton, and Larry Levitt, How the Loss of Cost-Sharing

Subsidy Payments is Affecting 2018 Premiums, (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2017),

https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-the-loss-of-cost-sharing-subsidy-payments-is-affecting-2018-

premiums/.

30

Rabah Kamal, Cynthia Cox, Care Shoaibi, Brian Kaplun, Ashley Semanskee, and Larry Levitt, An Early Look at

2018 Premium Changes and Insurer Participation on ACA Exchanges (San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation,

August 2017), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/an-early-look-at-2018-premium-changes-and-insurer-

participation-on-aca-exchanges/.

31

Rabah Kamal, Cynthia Cox, Rachel Fehr, Marco Ramirez, Katherine Horstman, and Larry Levitt, How Repeat of

the Individual Mandate and Expansion of Loosely Regulated Plans are Affecting 2019 Premiums, (San Francisco,

CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2018), https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/how-repeal-of-the-

individual-mandate-and-expansion-of-loosely-regulated-plans-are-affecting-2019-premiums/.

32

Karen Pollitz and Gary Claxton, Proposals for Insurance Options That Don’t Comply with ACA Rules: Trade-offs in

Cost and Regulation, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2018), https://www.kff.org/health-

reform/issue-brief/proposals-for-insurance-options-that-dont-comply-with-aca-rules-trade-offs-in-cost-and-regulation/.

33

Karen Pollitz, Michelle Long, Ashley Semanskee, and Rabah Kamal, Understanding Short-Term Limited Duration

Health Insurance (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2018), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-

brief/understanding-short-term-limited-duration-health-insurance/.

34

MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, Elizabeth Hinton, Larisa Antonisse, and Cornelia Hall, Section 1115

Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: The Current Landscape of Approved and Pending Waivers, (Washington, DC:

Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2018), https://www.kff.org/report-section/section-1115-medicaid-

demonstration-waivers-the-current-landscape-of-approved-and-pending-waivers-issue-brief/.

The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer 22

35

Kaiser Family Foundation, Proposed Changes to “Public Charge” Policies for Immigrants: Implications for Health

Coverage, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2018), https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-

sheet/proposed-changes-to-public-charge-policies-for-immigrants-implications-for-health-coverage/.

36

Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Marketplace Enrollment, 2014-2019,” Trend Graph: United States

2014-2019, accessed January 2019, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-enrollment.

37

Robin Rudowitz, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Cornelia Hall, Year End Review: December State Data for Medicaid

Work Requirements in Arkansas (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2019),

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-data-for-medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas/.

38

MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, and Barbara Lyons, Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience

and Perspectives of Enrollees (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2018),

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas-experience-and-perspectives-of-

enrollees/.

39

Kaiser Family Foundation, In Focus: Immigrant Families, including Immigrants Lawfully in the U.S. and Those Who

Are Undocumented, Report Rising Fear and Anxiety Affecting Their Daily Lives and Health (Washington, DC,

December 13, 2017), https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/press-release/in-focus-immigrant-families-including-

immigrants-lawfully-in-the-u-s-and-those-who-are-undocumented-report-rising-fear-and-anxiety-affecting-their-daily-

lives-and-health/.

40

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2013 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

41

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

42

Ibid.

43

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-Year Estimates.

44

Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Distribution of Eligibility for ACA Health Coverage Among those

Remaining Uninsured as of 2017,” accessed January 2019, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-

indicator/distribution-of-eligibility-for-aca-coverage-among-the-remaining-uninsured/.

45

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis based on 2017 Medicaid eligibility levels and March 2017 Current Population

Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

46

Tricia Brooks, Karina Wagnerman, Samantha Artiga, and Elizabeth Cornachione, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility,