1

Spending Review 2018

Current and Capital Expenditure on Social

Housing Delivery Mechanisms

DANIEL O’CALLAGHAN AND PAUL KILKENNY

IGEES UNIT AND

HOUSING, PLANNING AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT VOTE

JULY 2018

This paper has been prepared by IGEES staff in

the Department of Public Expenditure & Reform.

The views presented in this paper do not

represent the official views of the Department of

Public Expenditure and Reform or the Minister

for Public Expenditure and Reform.

2

Summary

There are a number of delivery mechanisms in place to provide social housing support including the construction and

acquisition of social housing stock, the leasing of units and the provision of support within the private rental market

through the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) and the Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS). Expenditure on social

housing has increased substantially in the last number of years and is just 4% below peak levels, as output has started to

increase in line with Rebuilding Ireland targets. The composition of expenditure has changed however, with a greater

proportion of current expenditure supports. There are a variety of objectives behind the mix of delivery mechanisms

including; the appropriateness of support, flexibility and speed of delivery, use of funding mechanisms and value for

money. Efficiency and long term value for money is a key consideration given the level of Exchequer funding.

Key Findings

Based on the limited available data, indicative cost analysis across six Local Authorities indicates that over the

long term, the relative cost effectiveness of each of the delivery mechanisms differs across areas.

It is estimated that, based on the Local Authority areas analysed, the net present cost (NPC) of delivering units

through mechanisms such as HAP, RAS and leasing is higher than construction and/or acquisition in Fingal and

Meath where prices within the general housing market are higher, while the NPC of those mechanisms is

generally either at or below the estimate for construction in other areas where prices in the wider market are

not as high (e.g. Mayo and Tipperary).

The limitations involved with the analysis emphasise the need to carry out similar work across other Local

Authority areas as further data becomes available and as output picks up. In particular, this would allow for a

comprehensive analysis of relevant costs taking into account factors which may vary by Local Authority area (e.g.

prices within the wider housing market; the availability and cost of land; demand for social housing).

While certain mechanisms have been shown to be relatively more or less costly across Local Authority areas,

there are other considerations in terms of the overall mix of delivery mechanisms which influence their design

and implementation including the speed at which they can be delivered, their effect on the wider housing

market, the quality and appropriateness of accommodation, sectoral capacity, flexibility etc.

As such, within the context of policy objectives and wider issues, the relative cost of delivering social housing

should be an important consideration in determining the mix of support mechanisms used, particularly in the

medium to long run.

There are also a number of wider policy considerations that are relevant including;

o effectiveness and targeting of support;

o sustainability and equity of tenant contributions across Local Authority areas; and

o appropriate and cost effective social housing stock management/renewal and the overall capacity of, and

impact on, the wider housing market

Greater availability of data in a number of areas including administration, maintenance and renewal costs

would assist policy makers and planners in assessing ongoing financial implications of the various delivery

mechanisms.

3

Contents

1. Introduction and Context .................................................................................................................. 5

2. Overview of Policy Developments ..................................................................................................... 9

3. Overview of Delivery Mechanisms .................................................................................................. 13

Construction .................................................................................................................................................. 13

Acquisition ..................................................................................................................................................... 14

Leasing ........................................................................................................................................................... 15

Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS) .......................................................................................................... 16

Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) ............................................................................................................... 16

4. Rationale and Objectives ................................................................................................................ 17

5. Expenditure Analysis and Social Housing Output ............................................................................. 22

6. Cost and Efficiency Analysis ............................................................................................................ 27

7. Wider Policy Issues ......................................................................................................................... 38

8. Conclusions .................................................................................................................................... 41

Appendix One – Social Housing Programmes ................................................................................................... 44

Appendix Two – Previous Research and Cost Analysis Methodology ............................................................... 45

Appendix Three – Additional Results from Cost Analysis .................................................................................. 46

Appendix Four – Results of Sensitivity Analysis ................................................................................................ 47

4

Acronyms

AHB

Approved Housing Body

IGEES

Irish Government Economic and

Evaluation Service

C&AG

Comptroller and Auditor General

LA

Local Authority

CALF

Capital Advance Leasing Facility

LPT

Local Property Tax

CAS

Capital Assistance Scheme

NARPS

National Asset Residential Property

Services

CHR

Centre for Housing Research

NDFA

National Development Finance

Agency

CLSS

Capital Loan and Subsidy Scheme

NDP

National Development Plan

CSO

Central Statistics Office

NOAC

National Oversight and Audit

Commission

DEASP

Department of Employment Affairs

and Social Protection

NPC

Net Present Cost

DHPLG

Department of Housing, Planning and

Local Government

P&A

Payment and Availability Agreement

DPER

Department of Public Expenditure

and Reform

PPP

Public Private Partnership

EIB

European Investment Bank

PSC

Public Spending Code

ESRI

Economic and Social Research

Institute

RAS

Rental Accommodation Scheme

EU

European Union

RLS

Repair and Leasing Scheme

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

RTB

Residential Tenancies Board

GGB

General Government Balance Sheet

SHCEP

Social Housing Current Expenditure

Programme

GGD

General Government Debt

SHIP

Social Housing Investment

Programme

HAP

Housing Assistance Payment

SHLI

Social Housing Leasing Initiative

HFA

Housing Finance Agency

UCCs

Unit Cost Ceilings

5

1. Introduction and Context

The State plays an important role in assisting those in need of housing support through a variety of

mechanisms. A number of policy measures have been implemented in recent years to increase the provision

of support in the context of wider housing market pressures. The Rebuilding Ireland strategy targets a

significant increase in social housing output using a variety of delivery mechanisms including the construction

and acquisition of units, long term leasing and supporting households to access the private rented market.

This paper has been completed as part of the 2018 Spending Review process. The Spending Review, as noted

in the 2017 Expenditure Report, is focused on ensuring all expenditure is considered when Government are

making budget decisions and generating analysis to further embed the principles of expenditure efficiency and

effectiveness into the wider budgetary process. The analysis presented within this paper builds upon a

previous paper entitled ‘Analysis of Current Expenditure on Housing Supports’ which was completed as part

of the 2017 Spending Review process.

Objectives of Paper

The analysis completed for the 2017 Spending Review focused on housing supports provided through current

expenditure (Rent Supplement, Leasing, Rental Accommodation Scheme and Housing Assistance Payment). It

provided analysis of relevant scheme costs in the context of price trends in the wider housing market. The

paper highlighted the need for further research and analysis on the relative efficiency and effectiveness of the

delivery mechanisms across both capital and current expenditure. As such, the purpose of this analysis is to

build upon the work completed last year and to focus on the comparative analysis of delivery streams,

particularly related to cost effectiveness. The objectives of this paper are thus to:

Analyse the trend and composition of current and capital expenditure in the area of social housing

delivery over the last number of years.

Detail social housing output relevant to both capital and current expenditure over time.

Set out and consider the relevant policy context and the rationale for the supports, as well as their

effectiveness and efficiency in addressing social housing demand.

Analyse the long term comparative value for money of delivering social housing via current and capital

expenditure.

Consider wider policy issues which are of relevance to the consideration of social housing delivery, as

appropriate.

Structure of Paper

The structure of the paper reflects the relevant objectives set out above and is broadly in two parts. First, the

paper provides an overview of policy developments in the area of social housing, the mechanisms to deliver

social housing and the rationale and objectives linked to provision. Secondly, the paper analyses trends in

6

expenditure and output across both capital and current delivery, the long term costs of each of the streams is

analysed across a select number of Local Authority areas and, finally, consideration of wider related policy

issues. This paper has been completed by the Housing Vote and the IGEES Unit within the Department of Public

Expenditure and Reform (DPER) and has been overseen by a steering group comprising representatives from

both DPER and the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government (DHPLG).

Context for Analysis

The wider context for the paper reflects the complexities of the housing market and issues pertaining to both

supply and demand. The 2017 Spending Review paper set out a detailed analysis of issues such as housing

market dynamics and trends, purchase and rental price trends, social housing demand, and social housing

supply/policy. In addition, these various wider issues have been covered in greater detail elsewhere

1

.

While not reanalysing these trends in detail here, it is necessary to consider the key points of context to frame

the analysis contained within the report and to expand the rationale for the choice of topic. Figures 1-4

highlight trends in property prices, average rents, housing output (measured through registrations and

connections) and social housing demand. The following high level points which have been established in more

detail elsewhere are of note for this analysis;

House prices have increased significantly since March 2013 (+75% nationally, +82% in Dublin based on

CSO Residential Property Price Index) reflecting demand, supply and economic trends but remain below

peak levels (22% lower than April 2007 nationally and in Dublin).

Average rents have increased by around 35% nationally since the low point at the start of 2012 with

sharper increases in the capital (+53% in Dublin). Average rents are now above their previous levels at

the end of 2007 by 3% nationally and by 13% in Dublin based on Residential Tenancies Board (RTB) data,

demonstrating the particular pressures in the Dublin market.

Government provided for a Rent Predictability Measure in December 2016 which introduced the concept

of Rent Pressure Zones (RPZs), to moderate the rate of rent increases in those areas of the country where

rents are highest and rising quickly. Once an area is designated a Rent Pressure Zone, rent increases are

capped at a maximum 4% per annum for up to three years. Data from the latest quarterly RTB rent indices

provides some initial evidence that the introduction of the RPZs is beginning to have some positive effect

on rent inflation, particularly in Dublin

2

.

1

E.g. D/Finance (2018) ‘Housing and Property Sector Chartpack’. Accessed at http://www.finance.gov.ie/wp-

content/uploads/2018/02/180214-Housing-and-Property-Sector-Chartpack-February-2018.pdf

2

RTB Rent Index Q1 2018: ‘On a quarter-on-quarter basis, the rental price inflation slowed in Q1 2018 to 0.4 per cent which is the

slowest rate of growth since Q1 2017. This may be partly explained by seasonal factors as the first quarter of the year has historically

displayed a slowdown in growth. Notwithstanding this seasonal pattern, rental inflation has slowed between Q4 2017 and Q1 2018’.

7

Figure 1-4: Housing Context: Property Prices, Average Rents, Housing Output and Social Housing Need

Sources: As stated. Note: Other data sources are available to track house prices and rental prices (e.g. CSO, daft.ie, etc.).

In terms of total housing output, CSO data available over the period between 2011 and 2017

demonstrates that the number of new dwelling has increased steadily from a low base since 2013 to a

total of 14,446

3

in 2017 up from 4,575 in 2013.

Although there are methodological issues with comparing social housing need over time, it is evident that

a significant number of households have been deemed to have a social housing need but are not

currently accessing a social housing support with 85,799 households on the list as of June 2017. There

was a 6.3% decrease in the number of households on the list between September 2016 and June 2017.

Exchequer investment on social housing has increased significantly since 2015, with the capital allocation now

exceeding current funding provision in 2018. Given previous and ongoing fiscal constraints, increasing the level

of social housing provision necessitated innovative delivery solutions and associated funding mechanisms.

3

Note: In addition 1,091 completed dwellings in unfinished housing developments. See:

https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-ndc/newdwellingcompletionsq12018/overview/

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Index (100:2005)

Figure 1: Residential Property Price Index,

Jan 2005 - Feb 2018

National National excl. Dublin Dublin

Source: CSO

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

Index (100:2007Q3)

Figure 2: RTB Rent Index,

2007 Q3- 2017 Q4

National Outside GDA Dublin

Source: RTB

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Thousands

Figure 3: New Dwelling Completions,

2011-2017

Single Scheme Apartment

Source: CSO

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1993

1996

1999

2002

2005

2008

2011

2013

2016

2017

Net Need ('000)

Figure 4: Net Household Need,

1993-2017

Source: Housing Agency. Note: Net Need excludes those already

recieving social houisng support. Data not comparable pre-2013.

8

These points will be discussed further in the report under expenditure analysis and wider policy issues

sections.

As such there have been a number of significant developments within the housing market and the policy

measures that are being delivered through Rebuilding Ireland entail a number of different delivery

mechanisms that operate within this context. It is evidently important to consider issues around efficiency and

effectiveness in relation to the provision of social housing support on an on-going basis. While the operation

of the housing market and the provision of necessary support is a complex issue with many different drivers

and factors, the objective of this paper, as outlined, is to add to the overall level of analysis within this policy

area through focusing on medium term costs and related issues.

9

2. Overview of Policy Developments

Rebuilding Ireland states that Government policy aims ‘to ensure that to the greatest extent possible, every

household can access secure, good quality and affordable housing suited to its needs and located within

sustainable communities’. This policy objective is focused on increasing the supply of housing generally, and,

through combining public, voluntary and private investment, increasing the supply of social housing stock,

thereby meeting the housing needs of those who need long-term support in a way that offers flexibility to

both Local Authorities and social housing recipients. To put current policy in context and to understand how

it has evolved, it is useful to review responses to social housing needs and trends in the provision of social

housing solutions over time.

Historical Context

While Ireland’s first urban Local Authority (LA) housing scheme was completed in 1879 by Waterford City

Council, public housing was provided earlier in Dublin by philanthropic agencies such as the Guinness Trust

and the Dublin Artisan’s Dwellings Company

4

. By 1914, Irish LAs had completed approximately 44,701

dwellings, almost double that in Great Britain. Little progress was made until the 1932 Housing Act in tackling

urban housing problems.

By the late 1950s, social housing output accounted annually for between a third and a half of total house

building. With the 1966 Housing Act, LAs were given powers enabling them to allocate publicly owned

dwellings according to a scheme of letting priorities giving preference to those households in greatest need

(Ibid). The Ballymun Towers in Dublin exemplified this new policy direction. From 1980 onwards, social housing

policy can be characterised as one of residualisation

5

. By 1994 almost 50% of LA housing tenants had incomes

below 40% of average income. Improvements in the Irish economy in the early 1990s led to estate

4

Norris, M. and Redmond, D. (eds). ‘Social Housing’ Housing Contemporary Ireland, Policy, Society and Shelter

5

Residualisation refers to the tendency for the social housing sector “to cater for an increased proportion of deprived people and to

cater more exclusively for this group”.

Figure 5: Local Authority and AHB Social Housing Output 1980 – 2002

Source: Social Housing, Michelle Norris 2006

10

regeneration and tenure mixed social housing provision under Part V of the Planning & Development Act 2000.

Research also notes the greater involvement of the Voluntary & Cooperative (Approved Housing Body or AHB)

sector during this decade as per Figure 5 above. The graph also demonstrates the level of tenant purchase of

LA dwellings, which was a provision under the 1966 Housing Act. The level of Exchequer Capital funding for LA

housing and associated output increased steadily from 2004 to 2008/2009 alongside new current expenditure

supports such as the Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS).

Recent Policy Evolution (2009-2016)

Driven by the requirement to achieve fiscal consolidation during the economic crisis, 2009 saw the beginning

of major reductions in the allocation of Exchequer capital investment for the construction of social housing

and a switch from capital investment to current expenditure. From a position of accounting for 70% of social

housing expenditure in 2008, capital investment’s share was almost the same as current expenditures by 2010.

Within an increasing current expenditure budget, there was also a shift away from Rent Supplement to the

consolidation of all housing supports in the local government sector.

The RAS was introduced in 2004 and was followed by the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) in 2014. Both

schemes support the accommodation of households with a long-term housing need in the private rented

sector and unlike Rent Supplement, households do not lose their support if their income increases. In 2011,

leasing under the Social Housing Current Expenditure Programme

6

(SHCEP) was introduced. This facilitated

privately owned properties, including those owned by AHBs, to be harnessed for social housing for a minimum

of 10 years. The various leasing mechanisms have evolved in the period since to reflect different funding

mechanisms. This reorientation towards addressing a greater proportion of social housing need through

current expenditure delivery mechanisms enabled more needs to be addressed in the short run within the

tightened budgetary environment. This approach was facilitated initially by the unprecedented growth and

over supply of housing leading up to the property crash.

The Social Housing Strategy 2020, published by the Government in November 2014, provided a framework for

off-balance sheet delivery of social housing units underpinned by a multi-annual capital and current housing

programme. This acknowledged the potential leveraging of off-balance sheet mechanisms and Public Private

Partnership (PPP) procurement opportunities to deliver social housing.

In terms of overall social housing demand, the overall net household need as of 28

th

June 2017 was 85,799.

This is a 6.3% or 5,801 decrease since September 2016. It is important to note that the Summary of Social

Housing Needs Assessment figures are a point in time analysis. From month to month there may be additional

individuals and families presenting and being deemed eligible for social housing and who may avail of

6

SHCEP supports the delivery of social housing by providing financial support to LAs and AHBs for the long term leasing of houses

and apartments from private owners and developers. Properties made available under the programme are used to accommodate

households from LA waiting lists.

11

immediate support through the HAP. Given the persistent level of social housing need and the lack of housing

supply generally, the Government introduced the current action plan for housing and homelessness,

Rebuilding Ireland, in July 2016.

Table 1: Rebuilding Ireland Delivery Targets, 2016-2021

Category

Target

2016

Output

2016

Target

2017

Output

2017

Target

2018

Target

2019

Target

2020

Target

2021

Overall

16-21

Build

2,260

2,965

3,200

4,054

4,969

6,385

7,716

8,907

33,437

Acquisition

1,755

1,957

1,250

2,214

900

1,025

800

800

6,530

Lease

225

792

600

827

2,000

2,130

2,631

2,450

10,036

Subtotal

4,240

5,714

5,050

7,095

7,869

9,540

11,147

12,157

50,003

RAS

1,000

1,256

1,000

890

600

600

600

0

3,800

HAP

12,000

12,075

15,000

17,916

17,000

16,760

13,000

10,000

83,760

Subtotal

13,000

13,331

16,000

18,806

17,600

17,360

13,600

10,000

87,560

Overall Total

17,240

19,045

21,050

25,901

25,469

26,900

24,747

22,157

137,563

Source: DHPLG

Rebuilding Ireland (2016 – 2021)

Rebuilding Ireland: An Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness includes five pillars of actions designed to

address homelessness, accelerate social housing supply, build more homes and improve the rental sector as

well as utilising existing stock better. The original ambition was to provide 47,000 long-term social housing

homes through Build, Acquisition and Leasing programmes and, in addition, to provide a further 87,000

flexible housing supports through the HAP and RAS between 2016 and 2021. There is public demand for a

social housing structure that is blended to suit the varied needs of people and one that utilises the housing

stock across the State in an efficient way. While there are multiple underlying schemes facilitating delivery,

what matters ultimately is not the delivery mechanism but the availability of a home that is suited to people’s

needs.

Arising from a review of Rebuilding Ireland undertaken in Q3 2017, additional funding was provided to support

the delivery of social housing to 2021. With the additional funding secured, the overall level of ambition under

Rebuilding Ireland was increased to 50,000 with a rebalancing of delivery more towards social housing

construction projects driven by LAs and AHBs. Overall the Government has now committed €6 billion to

support the accelerated delivery of 50,000 additional social housing homes by end 2021, through build

(33,500), acquisition (6,500) and leasing (10,000) programmes.

12

Figures 6 and 7: Rebuilding Ireland Delivery Targets, 2016-2021 and DHPLG Capital Allocations, 2018-2022

The National Development Plan (NDP) (2018 -2027)

By 2040 the population of Ireland is expected to reach almost 6 million with a need for 550,000 more homes

and the creation of 660,000 additional jobs to achieve and maintain full employment. The need to provide in

excess of half-a-million more homes over the period to 2040 corresponds to a long-term trend of 25,000 new

homes every year as outlined in the NDP. A higher level of output is needed in the short to medium term to

respond to the existing deficit that has given rise to the housing crisis. Looking beyond 2020, sustained

economic growth and a growing population and rate of projected household formation will likely require, as

stated in the NDP, an increase in annual housing output in the following years to 30,000-35,000 homes

annually up to 2027, to address the supply deficit that has built up since 2010 from an underperforming

housing market. As part of this, it will be necessary for DHPLG to oversee a steady rate of social housing output

that is appropriate to the shifting demographics outlined above. In order to meet this challenge the NDP

provides that “over the next decade €11.6 billion will be provided for investment in social housing”, yielding a

minimum of 12,000 additional social houses per annum from 2021.

This level of provision will be maintained over the remainder of the period of the NDP, resulting in an estimated

112,000 households having their housing needs met by 2027. It should be noted that the ambition under the

NDP includes a continuing upward trajectory of leasing activity, therefore, demonstrating a continuing

commitment to harnessing private and institutional capital investment in social housing.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Target

2016

Output

2016

Target

2017

Output

2017

Target

2018

Target

2019

Target

2020

Target

2021

Thousands

HAP RAS Lease Acquisition Build

Source: DHPLG

1.63

2.03

2.08

2.21

2.28

0.88

1.01

1.14

1.15

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

€ Billion

NDP Capital Allocations (DHPLG Total)

Rebuilding Ireland

Source: DPER

13

3. Overview of Delivery Mechanisms

Social housing support is provided through a variety of delivery mechanisms which are funded through capital

and current expenditure and delivered by LAs and AHBs. The purpose of this section is to set out the detail of

these delivery mechanisms.

Overview of Delivery Mechanisms

In delivering social housing support, there are a number of programmes which are in place across different

elements of delivery. For instance, as set out in Appendix One, there are delivery mechanisms through LA

construction and acquisition; there are programmes which support LAs to bring vacant houses, in need of

substantial works, back to productive use, such as the voids programmes (which includes the derelicts and “2

into 1” programmes); there are measures to assist the delivery of new social housing supply through AHBs;

there are programmes targeted at particular groups such as those with disabilities, older people and the

travelling community; and there are programmes to deliver social housing support through the private market.

For the purposes of this paper, the analysis will focus on a number of specific delivery mechanisms for

additional social housing units. In doing so, it is useful to simplify the delivery mechanisms in to five distinct

strands as set out in Figure 8. These strands relate to the construction, acquisition and leasing of additional

units, for social housing by both LAs and AHBs, sourced either directly from the market or through

construction/acquisition, the RAS and the HAP.

Figure 8: Simplistic Overview of Delivery Mechanisms

Construction

The delivery of social housing units through construction by LAs is funded through the Social Housing

Investment Programme (SHIP). Under this delivery mechanism, additional social housing units are delivered

through construction projects directly managed by LAs or through turnkey scheme agreements with

developers. There are a number of phases for housing construction projects with the overall pipeline of

development being made up of projects at various levels of progression. The phases include capital appraisal,

pre-planning design, pre-tender costs, tender process, site start and completion. In delivering the construction

programme, DHPLG manages the Exchequer funding; works with LAs on their individual projects; sets targets

with each LA; assesses project applications for quality and value for money purposes; and, manages and

reports on the overall social housing build programme. It is the LAs who identify the social housing need and

delivery projects to meet that need. Unit Cost Ceilings (UCCs) are utilised by LAs for the delivery of new build

LA social housing projects. As well as contracting developers to construct social housing based on LA approved

design, the LAs also contract developers to deliver new social housing based on existing designs and planning

Social Housing Delivery Mechanisms

Construction

Acquisition

Leasing

RAS

HAP

14

permissions through turnkey arrangements. AHBs also use the turnkey arrangement to have new social homes

constructed. In some cases, turnkeys can involve the completion of unfinished developments, and potentially

provide early construction delivery and tackle unfinished estates around the country.

In addition to LAs engaging in direct construction, capital funding is also provided to AHBs to construct social

housing units. The properties are secured for social housing use and LAs nominate tenants from their housing

lists for accommodation in these units. AHBs take on all responsibility for the development of the properties,

the ongoing management and maintenance of the properties, as well as tenant management. Funding for this

activity is provided by LAs to regulated AHBs, either through the Capital Assistance Scheme (CAS) or the Capital

Advance Leasing Facility (CALF) and Payment and Availability model (P&A). The CAS is a fully funded

programme which targets the construction of new social housing units to cater for priority groups such as

older people or people with a disability. The CALF and P&A model will be described in more detail in the

section on leasing but supports the construction of additional housing which is subsequently utilised for social

housing.

There are also a number of other delivery streams which are related to construction of new social housing

homes. Part V of the Planning and Development Acts 2000 is a mechanism through which LAs can secure 10%

of new developments for social housing, or up to 10% of land zoned for housing development at “existing use

value” rather than “development value” for the delivery of social housing

7

. These obligations are in place for

developments of nine or more units or where the development is taking place on a site larger than 0.1

hectares. There are a number of alternative options to comply with Part V including constructing and selling

at discount relevant units or other units, granting a lease for houses (on or off-site) or a combination of these.

LAs can also agree that the Part V unit could be assigned to and/or managed by an AHB. Both the LA and AHB

utilise the existing funding structures to support this activity. As part of the overall build programme, activity

is also underway through regeneration to enhance the level of active social housing stock. Some €211 million

is being made available under the National Regeneration Programme to support the direct delivery of over

1,000 new social housing units over the lifetime of Rebuilding Ireland. Projects being funded under that

Programme have the potential to target the country’s most disadvantaged communities, including those

defined by the most extreme social exclusion, unemployment and anti-social behaviour. A number of major

schemes are being progressed in Dublin, Limerick and Cork.

Acquisition

The acquisition of units for use as social housing by LAs is also supported through the SHIP. Under this delivery

mechanism a LA acquires properties within the private market to provide it for use as social housing. In

7

The 2000 Act provided for up to 20% of land or 20% of Social and Affordable Housing but the Urban Regeneration and Housing Act

(2015) reduced this to 10% in both cases and removed the requirement for affordable.

15

acquiring suitable housing from the private market, LAs are provided with cost guidelines from DHPLG that

relate to the cost of unit purchase and any upgrades. A number of principles are also set out to guide LAs in

acquiring property including that they should consider the potential impact on the local market, tenure mix

and sustainability of the units. CAS is also available to AHBs to engage in the acquisition of accommodation for

specific priority groups as outlined in the section on construction above. Similarly, CALF and P&A can be

utilised by AHBs to support the acquisition of previously owned properties.

Leasing

The SHCEP (previously referred to as the Social Housing Leasing Initiative (SHLI)) recoups to LAs the cost of

dwellings sourced under SHCEP to be used for the purposes of providing social housing support. Long term

lease arrangements, entered into by LAs and AHBs, are secured at 80% - 85% of the current market rent for a

minimum of ten years. Availability agreements under CALF are secured by LAs with AHBs at 92% - 95% of the

current market rent. The level of discount on market rent that is agreed by the LA is a function of the amount

of risk transferred to the AHB regarding responsibility for ongoing maintenance (excluding structural) and

responsibility for tenant management.

The units funded under SHCEP come from a number of different sources. Firstly, the units can be leased

directly from the private sector by either a LA or an AHB. These units are privately owned, including from

institutional investors. These leases are typically classed as being either long term (typically 10-20 years) or

short term (1-10 years). In addition an Enhanced Leasing Scheme

8

was launched in January 2018 and is

targeted at private investment and new build or new to the market properties to be delivered at scale.

Secondly, units funded under SHCEP can be built or acquired by AHBs, with support available through the

CALF

9

. Finally, there are a number of other sources of units funded by SHCEP and secured under lease

arrangements including units leased to LAs and AHBs from NARPS (National Asset Residential Property

Services) (NAMA SPV), unsold affordable dwellings managed by AHBs for LAs and the AHB Mortgage to Rent

Scheme. Properties that are privately owned but vacant can be remediated and leased with support under the

Repair and Leasing Scheme (RLS)

10

and are also funded by SHCEP.

As such, units funded by SHCEP are delivered using a variety of streams, and as such the output falls under a

number of different high level delivery streams as set out in Table 2. Leased units can be subdivided into those

that are built or acquired by AHBs for social housing and secured under long term lease-type availability

agreements and those that have been directly leased from the private market.

8

For further information see: http://rebuildingireland.ie/news/minister-english-launches-enhanced-long-term-social-housing-

leasing-scheme/

9

The purpose of CALF is to provide financial support from LAs to AHBs via long term loan, to help with the purchase or construction

of housing units. The LA provides up to a maximum of 30% of the upfront capital cost. The remainder of the finance is then sourced

from either the private sector or the Housing Finance Agency

10

For further information see: http://rebuildingireland.ie/repair-and-leasing-scheme/

16

Table 2: SHCEP Leasing Mechanisms

Delivery Scheme funded by SHCEP Funding

Build

Units built by AHB with CALF support and secured by LAs with a P&A

11

Build

Part V Lease

Acquisition

Units purchased by AHBs with CALF support and secured with P&A

Lease

Repair and Leasing Scheme (Capital input also)

Lease

Direct Leasing, including new Enhanced Lease (LA & AHB)

Source: DHPLG

Rental Accommodation Scheme

The RAS was introduced in 2004 and targets the provision of housing through the private market for

households who have been in receipt of Rent Supplement long term (greater than 18 months) and have been

assessed as needing social housing. The scheme is delivered by LAs who, under the RAS model, source

accommodation from the private market and, in general, enter into a tenancy agreement with the landlord

and the RAS recipient. There are tenancies which are linked to the current tenant only and there are also

agreements based on availability over a defined period. The LA then makes a monthly payment to the landlord

based on market rates (guidance is for payment to equate to circa one month’s rent less than the market rate

over a given 12 month period (8% lower than market rate) to represent the level of risk transferred to the LA)

and the tenant pays differential rent to the LA based on the individual LA’s differential rent policy. Each

contract includes a periodic rent review (typically every two years).

Housing Assistance Payment

The HAP is a social housing support which provides access to accommodation within the private rental market.

Under the scheme, which was introduced on a phased basis from 2014, recipients are responsible for sourcing

their own accommodation within the private rented market. The resultant tenancy agreement is between the

landlord and the tenant. The rental payment to the landlord is made directly by LAs through a Shared Service

Centre; there is no contractual relationship between the LA and the landlord. The level of rent being charged

for the accommodation should generally be within the limits set down for the household type in that LA’s area

although there is an element of flexibility to this with LAs being able to use discretion of up to 20% above rent

limits (or 50% for homeless households). Tenants then pay a contribution towards their rent (differential rent)

to the LA based on their income and ability to pay. In terms of scheme eligibility, all households that qualify

for social housing support (as assessed by their LA) are eligible to apply for HAP. It is envisaged that all long

term recipients of Rent Supplement (longer than 18 months) will transfer to the HAP scheme on a phased

basis. An important difference between HAP and Rent Supplement is that it allows recipients to work full time

while Rent Supplement recipients can’t work for more than 30 hours per week.

11

A Payment and Availability Agreement is the contract which forms the basis of the lease arrangement between the LA and the AHB

for the purposes of leasing a housing unit, regardless of how the housing unit is sourced

17

4. Rationale and Objectives

The overall rationale for the provision of social housing support is clear. Housing is a basic requirement, but

the market, left to its own devices, may not ensure that all households are appropriately housed in an

affordable and sustainable manner. This is the main reason why a social housing programme exists. Where

there is inadequate supply of housing generally, rising rents can drive low income households out of the

private market to seek assistance from the State for their housing requirements. As indicated in the previous

section, there is an onus on Government to address the particular and often complex social housing needs of

those who require it with a social housing solution that is efficient and appropriate, as well as providing

value for money in the long term. The rationale and objectives of the individual social housing delivery

mechanisms will be explored further below in the context of this paper’s analysis. In accordance with DPER

Public Spending Code - Programme Logic Model, the rationale underpinning government funded schemes

should be regularly evaluated to ensure that the objectives are still relevant and that the schemes are

achieving their intended purpose. This section will outline the rationale for the various delivery mechanisms

in the context of evolving policy, the wider housing market and funding. Table 3 sets out the original objectives

and rationale underpinning the various delivery mechanisms. Following this, there are a number of objectives

or elements of rationale across the delivery mechanisms which are discussed.

Table 3: Original Objectives/Rationale for Housing Supports

Programme

Original Objectives

Construction

Adding to the overall stock is necessary in order to maintain, refurbish or renew existing stock, and

for the provision of units for the most vulnerable households.

Acquisition

Acquiring units from private market developments to add to social housing stock may be more

efficient where LAs do not have land to build, where the cost of construction is greater, or, where

the level of need is high and for speed and efficiency of delivery.

Leasing

Securing high quality properties for long-term social housing use from both the private market and

by leveraging the AHB sector as well as low cost borrowing or institutional investment, with a

minimal capital contribution, supplements the overall LA stock by construction.

RAS

Provide social housing support to long term rent supplement recipients, by limiting the barrier to

work, while maximising the use of available rental properties in a depressed housing market.

HAP

Unify social housing support (replacing Rent Supplement), remove barrier to work, and provide a

flexible form of social housing support, that can quickly address social housing need

Maintaining Level of Local Authority Social Housing

Under Rebuilding Ireland, a significant increase in direct build and acquisition of housing from the private

market by LAs and AHBs is targeted to meet the growing social housing need as evidenced by the LA waiting

lists. The rationale for maintaining a steady state of social housing stock is evidenced by the number of people

who have a housing need, the length of time spent on the social housing waiting list, and the complexity of

that need. According to the most recent Housing Agency summary of assessments

12

, 20,803 (24%) of

households are waiting more than 7 years for a social housing solution. While a HAP supported tenancy is

12

Housing Agency (2017) ‘Summary of Social Housing Assessments’.

18

available to anyone on the waiting list, some households in need of support may remain on a “waiting transfer

list” for a more permanent solution, thereby maintaining a demand for constructed or acquired social housing

units. In addition to length and type of need, a proportion of social housing is also required to supplement

units that may have either deteriorated over time or have been purchased by occupants under the Tenant

Purchase Scheme. Moreover, LAs need to ensure that type, design and location of units are suitable for a

proportion of those on the waiting list where a household member(s) has an enduring physical, sensory,

mental health or intellectual disability. Table 4 below demonstrates that this cohort accounted for 4,326 (5%)

of household need in 2017.

Table 4: Housing Agency Classification of Social Housing Need 2013 – 2017

2013

2016

2017

No specific accommodation requirements

79,978

77,880

73,072

Household member(s) has an enduring physical, sensory, mental

health or intellectual disability

3,919

4,456

4,326

Household member(s) is homeless

2,499

5,159

4,765

Household member(s) is a Traveller

1,632

1,778

1,472

Household member(s) is aged 65 or more

1,844

2,327

2,164

Total

89,872

91,600

85,799

Source: Housing Agency 2017

Value for Money

In addition to addressing the level of demand, across each of the delivery mechanisms, value for money for

the Exchequer is an important consideration. For example, one of the rationales behind the introduction of

leasing schemes in 2009 was that excess stock could be availed of for social housing at a time when rental

prices were low and capital funding was reduced. Similarly, as part of the recent review of Rebuilding Ireland,

it is a stated objective of DHPLG to refocus on building more social houses and this in part reflects the wider

trend in prices within the housing market and more significantly the need to increase supply to deliver on

social housing demand. As such, the achievement of value for money is an issue that spans across the delivery

mechanisms and this is impacted by developments within the wider housing market over time. The analysis in

section 6 of the report will focus on this area.

While the State will not gain an asset through the leasing arrangements there are a number of other factors

which mean that leasing is still good value in the long term for the State. The cost of delivering social housing

units under the traditional construction and acquisition model is not totally captured by the up-front capital

expenditure as each unit will carry a stream of ongoing costs over the long term including management,

maintenance and remediation. During the term of the lease, the responsibility for structural matters remains

with the property owner and not the LA. At the end of the lease term, the dwelling can require major

renovation or upgrading of property resulting in a substantial capital cost, which under leasing is not borne by

the LA but by the owner. Another factor that must be considered is that while under the traditional supply

mechanisms the State does gain an asset, the economic value of this asset to the State is limited to the extent

19

that properties may be purchased by tenants at subsidised rates

13

. Similarly, in terms of CALF projects, DHPLG

indicate that by passing on the development, void and management risk to a third party throughout the period

of the contract, LAs can focus their efforts and resources on developing their own pipeline of construction

activity, thereby increasing the overall capacity of the State to meet housing need. In some LA areas, there is

better value for money to be achieved through acquisition of units than through leasing – see section 7 below.

Speed and Capacity

As indicated in the policy chapter, current expenditure supported schemes, specifically those that draw on

existing and available properties in the private market, provide a level of flexibility and effectiveness in

addressing social housing need. Where a household is facing an immediate risk of homelessness, there is an

efficiency and responsiveness to HAP and RAS in providing social housing solution in a property that already

exists in the private rental market. With almost 41% of those with an unmet social housing need

14

already

living in the private rental sector, it makes sense that they continue to be assisted to live there. The Build

programme continues to be critical but it remains the case that more homes can be provided through

mechanisms such as leasing, RAS and HAP than could reasonably be expected to be delivered under

construction and acquisition programmes alone. Likewise, harnessing the capacity and capability of the AHB

sector in the provision of new social housing supply is important in terms of bolstering the speed and efficiency

of LAs to meet housing needs in their areas. LA capacity, particularly with respect to construction activity, was

significantly reduced during the fiscally constrained years. This reduced capacity continues to be corrected

and as such harnessing additional development and other expertise from the AHB sector will remain important

as the Build programme continues to be critical.

The current policy objective of the long term leasing of social housing homes is focused on increasing the

supply of social housing in a way that maximises the capacity of the sector, as well as the off-balance sheet

potential of private and other institutional investment in social housing. Long term lease arrangements,

entered into by LAs and AHBs, are secured at 80% - 85% of the current market rent for a minimum of ten years.

Availability agreements under CALF are secured by LAs with AHBs at 92% - 95% of the current market rent.

The level of discount on market rent that is agreed by the LA is a function of the amount of responsibility

transferred to the AHB for ongoing maintenance, (excluding structural) and responsibility for tenant

management. All of the leasing and availability contracts entered into by LAs are funded by the Department’s

SHCEP.

13

Tenant (Incremental) Purchase Scheme 2016 http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/home-ownership/tenant-purchase-

scheme/tenant-purchase. A review of the scheme has recently been completed and is due to be published by DHPLG

14

Housing Agency (2017) ‘Summary of Housing Needs Assessment 2017’.

20

Flexibility

Another objective of the differing delivery mechanisms is to provide flexibility within supports such that

varying types of accommodation and support can be provided based on need and circumstances as they evolve

over time. With an upturn in the economy becoming evident from 2014, one of the objectives in introducing

HAP was to operate as a labour activation measure, facilitating both a social housing solution and an

opportunity for a household to improve their circumstances. It is intended to replace RAS with HAP over the

course of Rebuilding Ireland, as a long term solution for those households living in the private rental sector,

currently in receipt of long term Rent Supplement. In an economy approaching full employment, the original

labour market rationale for this scheme may need to be reviewed, particularly with regard to differential rent

levels. Flexibility also needs to be made available to LAs as housing authorities to respond to the characteristics

of the local property market, for example where the cost of construction may be higher than the open market

value of existing properties, or where existing vacant properties, unfinished estates or underutilised land can

be brought into wider housing use with LA intervention.

Appropriate Accommodation and Sustainable Communities

Another objective which is common across the delivery mechanisms is that of providing suitable, sustainable

and integrated accommodation to those who require it. Rebuilding Ireland states that “irrespective of the

method of housing provision, citizens deserve to live in sustainable communities with an appropriate tenure

mix”. As such, the different delivery mechanisms can provide accommodation of varying natures and type. For

instance, mechanisms such as HAP, leasing, RAS and Part V build can potentially ensure that social housing

provision is dispersed rather than congregated in one place, which can have positive societal benefits that

counteract the residualisation of previous large scale social housing projects. Sustainable community proofing

is part of the evaluation process for new social housing projects to ensure an overconcentration of social

housing does not occur. The positive social externalities of mixed housing development are supported by

empirical peer reviewed research that demonstrates that such initiatives build stronger social ties and valuable

cultural capital

15

.

Funding Mechanism

The original rationale for leasing, using current funding, was that high quality properties could be obtained for

long-term social housing use in a way that minimised capital expenditure and the impact the on the General

Government Balance (GGB) Sheet, at a time when the State could least afford construction and acquisition.

The mechanism also enabled the State to utilise the opportunities provided by the AHB sector to continue

playing a significant role in the provision of social housing. New financial mechanisms for AHBs (CALF and P&A

Agreements) were introduced in 2011 to facilitate borrowing for the supply of new homes – traditionally the

15

Neighbourhood Social Mix as a Goal of Housing Policy, Galster, G. European Journal of Housing Policy Vol. 7, No. 1, 19–43, March

2007

21

sector has relied on 100% state grants. The move to more revenue funded social housing delivery options has

challenged the sector. However the availability of low cost debt financing to AHBs (as well as LAs) through the

Housing Finance Agency (HFA) and European Investment Bank (EIB) is also a consideration. Through CALF

funding, the AHB sector is facilitated to acquire and construct additional social housing that LAs can avail off

through a P&A agreement. Repayment, void and development risk are all passed from the State to AHBs

throughout the period of the on average 30 year contract. It is acknowledged that the CSO and Eurostat (2018)

recently reclassified the majority of Tier 3 AHBs (i.e. the largest) as part of general government. DHPLG have

confirmed they are undertaking an exercise, together with the Department of Finance and DPER as well as the

Housing Agency and HFA and the AHB sector, to clarify fully the policy implications of the decision. This is

particularly important in view of the Government’s commitment regarding AHB’s delivery role in the

Rebuilding Ireland Action Plan, and their planned contribution in the delivery of up to 16,800 units by 2021.

In 2015, DHPLG was tasked with identifying opportunities to harness the potential for private investment in

social housing to complement the availability of exchequer capital and current funded models. Following this

analysis, DHPLG has worked with the National Development Finance Agency (NDFA) to develop new

standardised leasing agreements and a centralised arrangement for engaging with potential investors and

housing providers. This work has resulted in the new Enhanced Leasing Scheme which was recently launched

and operates in addition to the existing lease arrangements which are essentially designed for smaller scale

providers. The arrangements have been prepared to ensure that the State’s interest is protected over the

period of the 25 year contract, while acknowledging the financial benefits of a long term secure contract with

the State, from the investor’s perspective.

Summary of Rationale and Objectives

This section has detailed some elements of the

varied objectives and rationale related to the

mechanisms for delivering social housing. While

the need to provide appropriate and efficient

support to those in need is clear, the analysis

here has detailed some of the objectives behind

the way social housing support is delivered

including the quality of support provided, the

speed, efficiency and flexibility of supports, the

maintenance of a social housing stock and, importantly, value for money. As set out above, value for money

is an important component influencing the overall mix of social housing delivery mechanisms such that the

most amount of support can be provided for a given level of input. Section 6 will provide further analysis on

the relevant cost of the schemes within the wider context as set out here.

Figure 9: Summary of Rationale and Objectives for

Social Housing Mechanisms

Social Housing

Mechanisms

Flexibility

Speed and

Efficiency

Value for

Money

Section 6

Funding

Mechanism

Other

Objectives

Type/Quality

of Accom.

Social

Housing

Stock

22

5. Expenditure Analysis and Social Housing Output

The following section sets out an analysis of public expenditure in the area of housing and related outturn.

The section first sets out trends in total expenditure before analysing the components of current and capital

expenditure in more detail and the associated social housing output.

Total Expenditure on Housing

As outlined in Figure 10 below, total public expenditure on housing in 2018 is €2.08 billion

16

and is just 4% (or

under €100 million) below the previous peak level of expenditure in 2008. Figure 10 sets out a trend analysis

of total public expenditure on housing between 2006 and 2018. As can be seen from the analysis, total

expenditure has increased rapidly since 2014 with a growth of €1.14 billion or 120% and stands at a level just

below the 2008 peak. A significant decrease in total expenditure between 2008 and 2013 is evident. In terms

of the composition of expenditure it is clear that there has been a significant change with capital equating for

70% in 2008 while it stands at 55% of the total in 2018. It should be noted that from 2015 onwards funding

has been made available for the delivery of housing programmes through surplus Local Property Tax (LPT)

receipts

17

and this is included in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Public Expenditure on Housing, 2006-2018

In terms of analysing total expenditure in more detail, it is evident that current expenditure is significantly

above previous peak levels while capital expenditure is nearly at 2006 levels. Figure 11 demonstrates the

change in current and capital expenditure against the level of funding in 2006. As can be seen, current

expenditure was relied on significantly to deliver necessary housing support between 2008 and 2015.

Meanwhile, capital expenditure as previously detailed decreased significantly following the economic crisis,

and in line with decreases in public capital in general, but has grown significantly in recent years and is almost

at 2006 levels. In addition, it can be seen that total expenditure on housing is reaching a similar proportion of

16

Note: Includes DHPLG expenditure on housing, funding through LPT receipts and expenditure by DEASP on Rent Supplement.

17

Certain LAs receive additional income from LPT compared to 2014 baseline levels and are directed to use this funding for the

provision of some housing and roads services.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

€ Billion

Capital Current

Source: DPER Databank and DHPLG. Note: Current and capital expenditure between 2015 and 2018 include LPT own funding.

Current expenditure includes Rent Supplement and Mortgage Supplement through DEASP.

23

overall expenditure as that seen in 2008. As a percentage of total gross exchequer expenditure, housing

accounts for around 3.2% while this previously stood at around 3.5% between 2006 and 2008.

Figures 11 and 12: Index of Capital/Current Expenditure; Housing as % of Total Exchequer Expenditure

When compared to the European Union (EU) average, available data indicates that Ireland spends a similar

amount on housing development as a % of GDP

18

, and more as a % of total Government expenditure, when

compared to the EU average. Data on Government expenditure from Eurostat indicates that Ireland spends

0.5% of GDP and 2% of Government expenditure on housing and community development respectively, while

the EU average is 0.6% of GDP and 1.3% of Government expenditure. In addition, the data indicates that in

2008 Ireland was significantly above the EU average in both measures with 1.9% of GDP and 4.6% of

Government expenditure versus 0.9% and 1.9% respectively for the EU average. While there are evidently a

number of different drivers of relative expenditure levels (e.g. population and labour market structure,

housing policy, wider housing market developments etc.) which mean the analysis should be interpreted with

caution, it does show that Ireland’s public expenditure in this area was above the EU average and is at or above

average levels as of 2016.

Analysis of Current and Capital Expenditure

In terms of the composition of current expenditure in 2018, HAP and Rent Supplement account for 51% while

leasing and RAS account for 26%. The remainder of current expenditure is largely targeted at specific groups

such as homeless services and traveller accommodation and support. While varying significantly in nature

(HAP is a social housing support and permits full time employment unlike Rent Supplement), it is of note that

total funding on HAP and Rent Supplement has increased 47% since 2015 from €326.7m to €480.8m in 2018.

18

Eurostat data is only available as % of GDP. Interpretation of outlined results is limited by stated issues with Ireland’s national

accounts data. It should be noted that alternative measures of Ireland’s national output are available (e.g. GNI*). See:

https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/in/acabi/amodifiedcurrentaccountbalanceforireland1998-2016/

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Index (100: 2006)

Capital Current

Source: DPER Databank and DHPLG. Note: Expenditure between

2015 and 2018 includes LPT own funding. Current expenditure

includes Rent Supplement and Mortgage Supplement through DEASP

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

2.5%

3.0%

3.5%

4.0%

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Housing as % of Total Exchequer Expenditure

Source: Author Analysis based on DPER data

24

For capital expenditure, 56% of the total in 2018 is for LA housing while 16% is through schemes linked to AHB

delivery (including CAS and CALF) and 11% is for schemes related to the regeneration and remediation of social

housing. As detailed earlier, capital expenditure has almost trebled since 2014 and will increase further in the

future under Rebuilding Ireland plans.

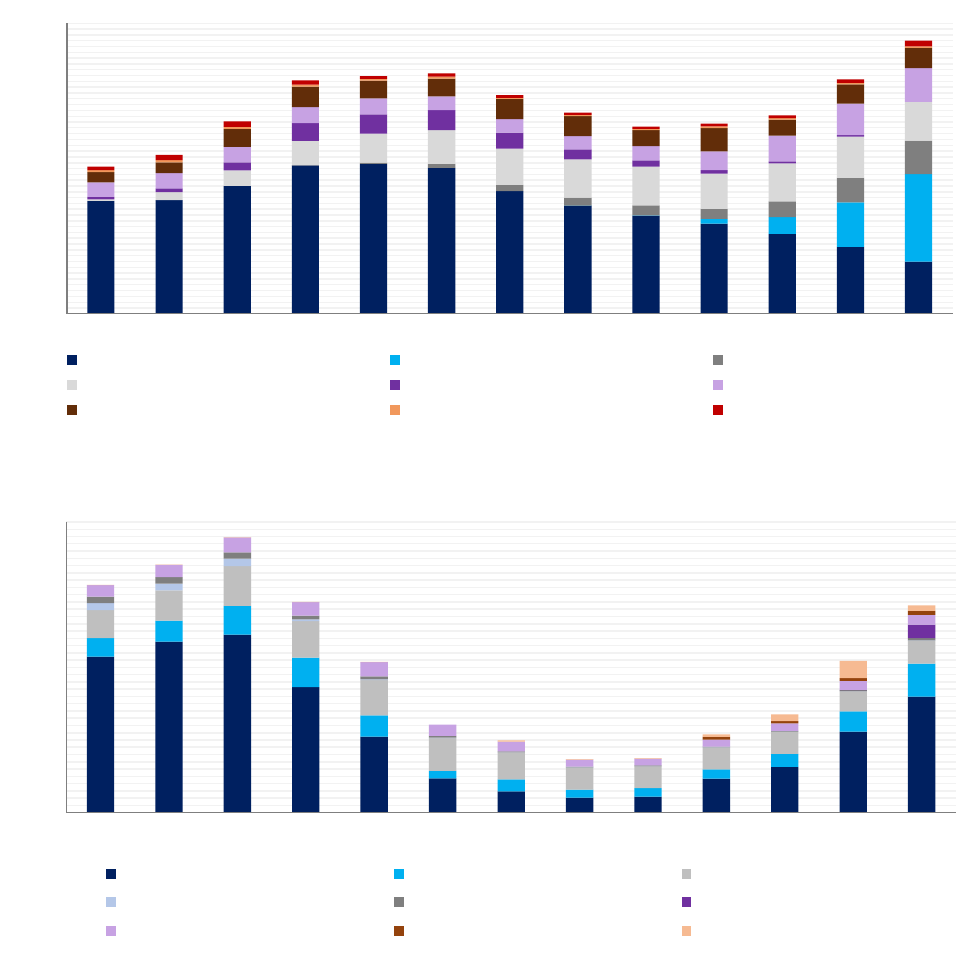

Figure 13: Current Expenditure on Housing, 2006-2018

Figure 14: Capital Expenditure on Housing, 2006-2018

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

€ Billion

Rent Supplement HAP SCHEP

RAS Mortgage Supplement Homeless Accom/Support

CLSS Travellers Accom/Support Other

Source: DPER Database and DHPLG. Note: Includes LPT Funding for 2015-2018

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

€ Billion

Local Authority Housing AHB Delivery LA Regeneration/Remedial

Subsidies and Allowances Social Inclusion Infrastructure Fund

Private Housing Grants Mortgage to Rent Other

Source: DPER Database and DHPLG. Note: Includes LPT Funding for 2015-2018. Note Mortgage to Rent captured under AHB delivery pre-2015

25

In conclusion, it is evident that there has been a significant increase in public expenditure in the area of housing

in recent years and total expenditure is only just below peak levels. In terms of composition, current

expenditure accounts for a higher percentage of the total than in 2008 but, as detailed earlier, capital

expenditure is expected to increase in future years under the Rebuilding Ireland plan.

Social Housing Output

In terms of trends in social housing output over time, it is evident that delivery has increased in recent years.

Overall social housing output has increased by 423% over the last thirteen years, from 6,117 units in 2004 to

25,901 in 2017. However, since 2015, the vast majority of this is accounted for by HAP, illustrating the

importance of current expenditure for social housing solutions during this period.

Figure 15: Social Housing Output, 2004-2017

Social Housing Output figures for 2016 and 2017 present outputs under the Rebuilding Ireland: An Action Plan

for Housing and Homelessness 2016-2021 delivery streams of Build, Acquisition and Leasing along with HAP

and RAS. This is consistent with the discrete annual targets set out under Pillar 2 of the Action Plan and

represents a move away from presenting the data grouped by funding stream and programme.

-

5

10

15

20

25

30

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Number of Units/Households (Thousand)

Build Acquistion RAS Leasing HAP Voids

Source: Analysis of DHPLG Data

Box 1 – Tax Expenditures in Support of Social Housing Provision

In addition to direct expenditure, there are a number of tax measures which are in place in the area of housing.

The Finance Act 2015 introduced a new relief for landlords who commit to let their property to tenants in receipt

of social housing supports for a minimum period of three years. It allows landlords to claim an increased expense

deduction for mortgage interest in their rental accounts – they will be able to claim 100% of relevant mortgage

interest, in place of the 85% generally allowed at present in respect of rented residential property (increased

from 80% in 2017 and 75% in 2016). Information on the numbers or cost will not be available until tax returns

for 2019 are filed, which will be in late 2019 or 2020 depending on the relevant Income Tax or Corporation Tax

periods. However, one of the criteria to avail of the relief is that a commitment must be registered with the

Residential Tenancies Board (RTB) at the commencement of the three-year period. Data from the RTB indicate

that uptake of the scheme to date has been positive, with over 2,991 tenancy commitments registered to date.

Qualifying tenancies have been registered in all 26 counties.

26

The LA New Build output figures consolidates all local authority new unit construction activity, including units

delivered by traditional construction, rapid build, turnkey, regeneration and Part V units, but do not include

the number of void local authority units brought back into use through local authority construction activity;

these are included in the All Build output figure which represents all construction activity undertaken by local

authorities and approved housing bodies (AHBs) to increase the supply of social housing. Further detailed

information on social housing output across a multiplicity of sub programmers is available from the housing

statistics section of the DHPLG website.

While the analysis above shows the output relevant to social housing delivery for each year since 2004, it is

also of interest to consider the overall stock of social housing units. Figure 16 sets out estimates of the total

number of social housing units (incl. Rent Supplement) from recent ESRI analysis. As the analysis shows, the

total number of units in 2016 is 253,000 and this is estimated to amount to 15% of all households (ibid). The

broad split of total supported units in 2016 is 56% LA units, 18% Rent Supplement, 15% RAS/HAP and 12% AHB

units.

Figure 16: Estimated Social Housing Units, Broadly Defined, 2004-2016

LA Units

AHB Units

Rent Supplement

RAS/HAP

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Thousand Units

LA Units AHB Units Rent Supplement RAS/HAP

Source: ESRI (2018) 'Social Housing in the Irish Housing Market'

27

6. Cost and Efficiency Analysis

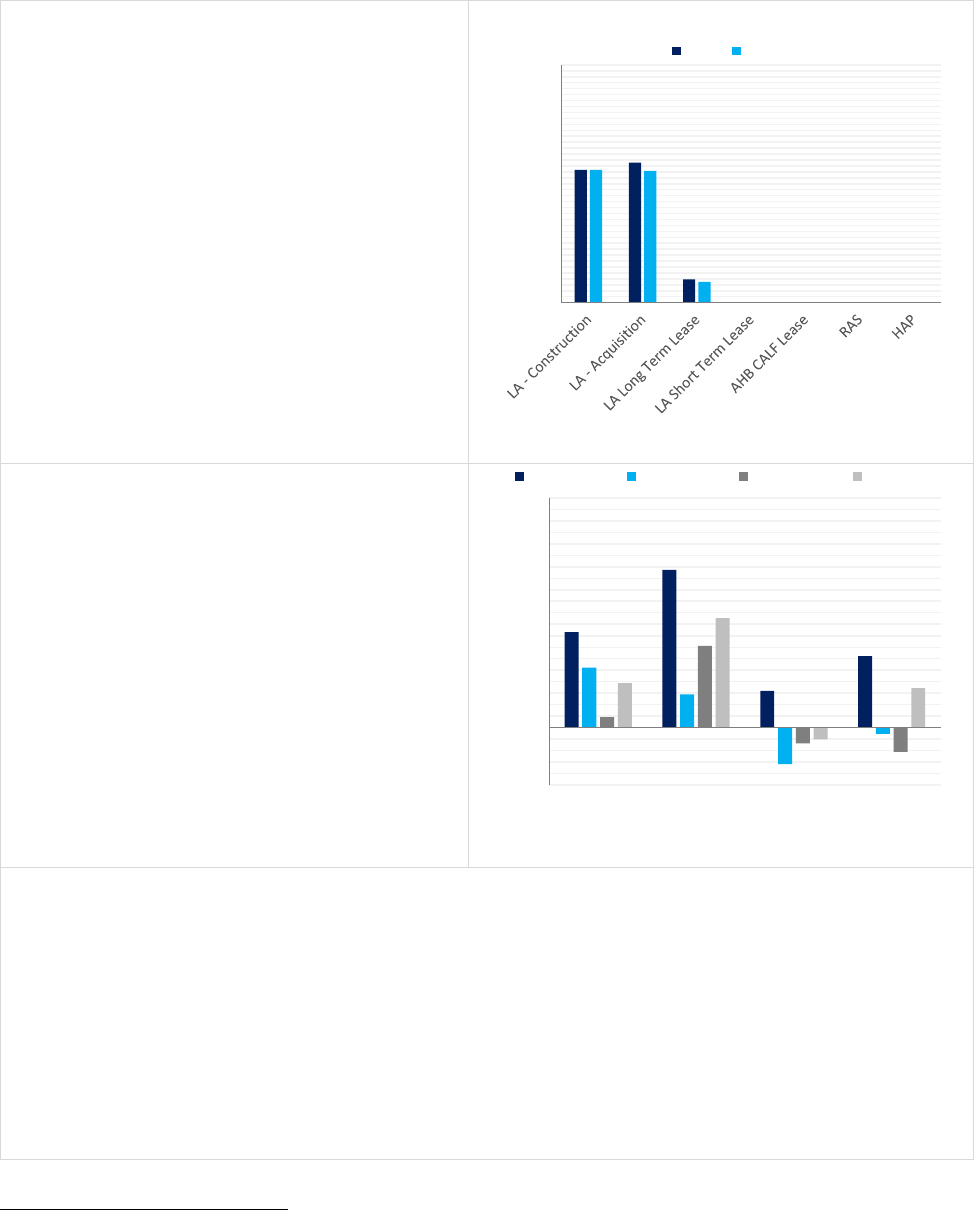

The purpose of this section is to analyse the relative cost of delivering social housing units through each of the

identified delivery mechanisms. In undertaking this analysis, the objective is to analyse the relative long term

cost implications and to assess value for money considerations. The section sets out in detail both the

methodology and results for the analysis.

Methodology and Approach

As detailed in section 3, there are a variety of mechanisms for delivering social housing. Each of these, from

construction and acquisition to leasing, RAS and HAP, imply different types of costs and revenues which occur

at different times. At a simple level, costs for both construction and acquisition are borne upfront while the

cost of units delivered through leasing, RAS and HAP are spread over a longer time period. As detailed in the

previous section there are also a variety of objectives and rationales across the delivery streams. Assessing

the comparative cost is evidently of importance given the need to provide suitable levels of support and

achieve value for money for the levels of public funding being expended.

In this regard, the purpose of this section is to look in detail at the relevant costs of delivery. As such, the

analysis presented here will look at modelling the financial flows

19

of each of the delivery mechanisms across

a selection of LA areas. In simple terms, each cost and revenue stream for construction, acquisition, leasing,

RAS and HAP over a standardised period will be captured and the net present cost (i.e. after discounting) will

be presented to compare relative costs. Figure 17 provides a graphical representation of this for two

hypothetical delivery mechanisms.

Figure 17: Overview of Net Present Cost Methodology

To complete the analysis, data was collated for a select number of LA areas. The LA areas were selected by

DHPLG based on data availability and to provide a spread of regions and markets. The areas included in the

analysis are Fingal County Council, Mayo County Council, Meath County Council and Kilkenny County Council.

To reflect the varying use of mechanisms across LA areas additional analysis was carried out on the areas of

Tipperary County Council and Wexford County Council.

19

Note: Analysis is general financial analysis and as such only financial flows are included and shadow prices are not applied.

Net Present Cost

One

Outflow

Inflow

Net Present Cost

Two

Discounting

Time

Time

28

Limitations and Data Availability

In conducting the cost analysis, data has been provided by DHPLG on the operation of the delivery mechanisms

across each of the LA areas. It should be noted from the outset that there are a number of factors which

present limitations to the analysis and should be kept in mind in interpreting any of the results. The two main

areas are set out below. Firstly, the level of output across each of the mechanisms has varied significantly in

recent years. For example, and as identified earlier in the paper, the level of units delivered through

construction is starting to increase but from a low base. As such, the level of cost data available is more limited

and as such estimated cost levels based on available evidence were provided (as described below). Secondly,

data on some elements of delivery are not routinely collected and/or collated across LAs and delivery

mechanisms. These are outlined in the data and assumptions section below and as such in places national

averages and/or assumptions have been used. Finally, there are a number of other general limitations. While

overall activity varies by mechanism it also varies across LAs. For instance, certain LAs have a higher level of

output across certain mechanisms, which means that the level of data on average costs of delivery necessarily

varies. There are also wider developments in the housing market of importance to the analysis being

undertaken. For example, costs related to leasing schemes and HAP will be impacted by rent levels in the wider

market. Given the identified level of pressure within the overall market the analysis presented here should be

seen as a point in time analysis. Given the identified limitations of the analysis, the overall results should be

read as indicative rather than definitive. Analysis of comparative medium term costs should be carried out at

regular intervals as social housing delivery expands and developments occur in the wider housing market.

Previous Analysis

Similar analysis in terms of both objective and methodology has been carried out on a number of previous

occasions. In 2009, the Centre for Housing Research (CHR, now the Housing Agency) commissioned Grant

Thornton and Fitzpatrick Associates to analyse capital funding schemes for AHBs

20

. As part of that report, some

analysis was included on the long term net present cost of delivering housing through capital funding,