Akron Law Review Akron Law Review

Volume 54

Issue 2

Criminal Justice Reform Issue

Article 3

2021

Life After Sentence of Death: What Becomes of Individuals Under Life After Sentence of Death: What Becomes of Individuals Under

Sentence of Death After Capital Punishment Legislation is Sentence of Death After Capital Punishment Legislation is

Repealed or Invalidated Repealed or Invalidated

James R. Acker

Brian W. Stull

Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview

Part of the Criminal Law Commons

Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will

be important as we plan further development of our repository.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Acker, James R. and Stull, Brian W. (2021) "Life After Sentence of Death: What Becomes of

Individuals Under Sentence of Death After Capital Punishment Legislation is Repealed or

Invalidated,"

Akron Law Review

: Vol. 54 : Iss. 2 , Article 3.

Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at

IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA.

It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of

IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected],

267

LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH:

W

HAT BECOMES OF INDIVIDUALS UNDER SENTENCE OF

DEATH AFTER CAPITAL PUNISHMENT LEGISLATION IS

REPEALED OR INVALIDATED

James R. Acker*

Brian W. Stull**

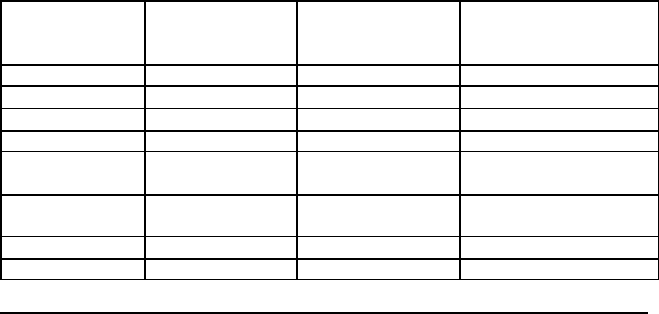

I. Introduction ........................................................... 268

II. Historical Practices in the United States .................. 276

A. American Jurisdictions Which Have Repealed or

Judicially Invalidated their Death-Penalty Laws 276

B. Execution Practices in Jurisdictions Following

Legislative Repeal or Judicial Invalidation of

Death-Penalty Statutes ..................................... 278

1. Alaska ........................................................ 278

2. Arizona....................................................... 279

3. Colorado..................................................... 282

4. Connecticut................................................. 284

5. Delaware .................................................... 286

6. District of Columbia .................................... 287

7. Hawaii ........................................................ 287

8. Illinois ........................................................ 288

9. Iowa ........................................................... 290

10. Kansas ........................................................ 291

11. Maine ......................................................... 293

12. Maryland .................................................... 294

13. Massachusetts ............................................. 295

14. Michigan .................................................... 296

15. Minnesota ................................................... 297

16. Missouri ..................................................... 298

17. New Hampshire .......................................... 299

19. New Mexico ............................................... 302

* Emeritus Distinguished Teaching Professor, School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany.

** Senior Staff Attorney, American Civil Liberties Union, Capital Punishment Project.

1

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

268 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

20. New York ................................................... 303

21. North Dakota .............................................. 305

22. Oregon ....................................................... 306

23. Rhode Island............................................... 310

24. South Dakota .............................................. 311

25. Tennessee ................................................... 312

26. Vermont ..................................................... 313

27. Virginia ...................................................... 315

28. Washington................................................. 316

29. West Virginia ............................................. 317

30. Wiscons in ................................................... 318

III. International Practice: Abolition and Post-Abolition

Executions ............................................................. 319

A. Canada ............................................................ 320

B. The United Kingdom........................................ 320

C. Europe and Other Countries Worldwide............ 322

IV. Juveniles and the Death Penalty .............................. 325

V. Conclusion ............................................................. 327

I. I

NTRODUCTION

What should become of individuals who are awaiting execution

following the repeal or judicial invalidation of capital punishment

legislation? Having lawfully been sentenced to death, should their

executions go forward? Or since death is no longer an authorized

punishment in their jurisdiction, should their capital sentences be

invalidated and replaced by life imprisonment? In states debating the

abolition of capital punishment, and in states that have taken that step, the

fate of individuals who have previously been sentenced to death looms

large, complicating repeal initiatives and raising urgent questions in the

aftermath of abolition. The ethically, politically, and legally fraught issue

of whether offenders previously sentenced to death should or can be

executed following a jurisdiction’s elimination of capital punishment has

repeatedly surfaced and inevitably must be confronted by the legislatures,

governors, and occasionally the courts, in states that have considered and

recently carried out the abolition of capital punishment.

2

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 269

In the continuing ebb and flow of support for the death penalty

throughout the nation’s history,

1

the advantage, at least temporarily, has

begun to tip in favor of the opponents of capital punishment. Public

opinion polls reflect that Americans’ enthusiasm for the death penalty has

steadily eroded over the past quarter-century. When asked if they were “in

favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder,” 80% of

Gallup Poll respondents replied affirmatively in 1996, compared to just

56% in 2019,

2

and 55% in 2020.

3

Provided with a specific choice between

punishments for murder, the death penalty or life imprisonment without

the possibility of parole, in 2019 a decisive majority expressed a

preference for incarceration over execution: 60% to 36%. This marked the

first time in the 34 years the Gallup Poll has posed the question that most

respondents favored the imprisonment option.

4

Even more dramatic trends are evident in practice. Death-sentencing

rates have plummeted over time. While 300 or more offenders were

dispatched annually to the nation’s death rows during the mid-1990s, just

34 new death sentences were imposed nationwide in 2019,

5

and 18 in

2020.

6

Executions have declined from a modern death-penalty era high of

1. See James R. Acker, American Capital Punishment Over Changing Times: Policies and

Practices, in HANDBOOK ON CRIME AND DEVIANCE 395 (Marvin D. Krohn, Nicole Hendrix, Gina

Penly Hall, & Alan J. Lizotte eds., Springer 2d ed., 2019).

2. Jeffrey M. Jones, Americans Now Support Life in Prison Over the Death Penalty, GALLUP

(Nov. 25, 2019), https://news.gallup.com/poll/268514/americans-support-life-prison-death -

penalty.aspx [https://perma.cc/7QF7-LFS6].

3. Death Penalty, GALLUP, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1606/death-penalty.aspx

[https://perma.cc/FTK7-Y9ZW].

4. Id.

5. The Death Penalty in 2019: Year End Report, DEATH PENALTY INFO. CTR., 1, 8 (2019),

https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/dpic-reports/dpic-y ear-end -reports/the-death-

penalty-in-2019-year-end-report [https://perma.cc/CH3J-LWYZ]. The new death sentences were

meted out in only 12 jurisdictions: seven in Florida; six in Ohio; four in Texas; three in California,

Georgia, and North Carolina; two in Pennsylvania and South Carolina; and one in Alabama, Arizona,

Oklahoma, and under federal authority. Id. at 11. Forty-three death sentences were imposed in 2018,

a year in which an estimated 16,214 murders and non-negligent manslaughters were committed

nationwide. Id. at 8; Uniform Crime Reports, 2018 Crime in the United States, FED. BUREAU OF

INVESTIGATION, https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018/topic-

pages/murder [https://perma.cc/LHF8-JLTT]. That total includes murders and non-negligent

manslaughters in both death-penalty and nondeath-penalty states, and of course not all of the criminal

homicides committed in death-penalty jurisdictions would qualify as capital murder. See Table 5

Crime in the United States, FED. BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION (2018), https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-

u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018/topic-pages/tables/table-5 [https://perma.cc/P5EE-37J6] (providing

state-by-state breakdown of murders and non-negligent manslaughters committed in 2018).

6. The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report, DEATH PENALTY INFO. CTR, at 1,

https://reports.deathpenaltyinfo.org/year-end/YearEndReport2020.pdf [https://perma.cc/UZ93-

X7YK].

3

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

270 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

98 in 1999,

7

to 22 conducted in 2019,

8

and 17 in 2020.

9

Twenty-seven

states now authorize capital punishment, a sharp reduction from the thirty-

eight that did in 2007.

10

Amidst debates about abolition or retention of capital punishment,

the question of what will become of individuals currently under sentence

of death if capital punishment legislation is repealed has emerged as a

prominent sticking point.

11

Its resolution is as consequential as it is

7. The Supreme Court’s decision invalidating capital sentencing statutes as inconsistent with

the Eighth Amendment in Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), and its subsequent decisions in

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) and companion cases, which upheld revised guided-discretion

death penalty laws, mark the beginning of the modern capital punishment era. See generally Carol S.

Steiker & Jordan M. Steiker, Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment, 101 THE

J. OF CRIM. L & CRIMINOLOGY 643 (2016).

The first execution under the new sentencing regimes occurred in 1977 when Gary Gilmore’s death

sentence was carried out by a Utah firing squad. See Deborah W. Denno, The Firing Squad as ‘A

Known and Available Alternative Method of Execution’ Post-Glossip, 49 U. MICH. J.L. REFORM 749,

757–58 (2016); see generally Welsh S. White, Defendants Who Elect Execution, 48 U. PITT. L. REV.

853 (1987).

8. The Death Penalty in 2019: Year End Report, supra note 5, at 1.

9. The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report, supra note 6, at 1.

10. Since 2007, eight states have legislatively repealed their death-penalty statutes (Colorado,

Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Virginia), while

courts in three states have invalidated death-penalty laws on constitutional grounds and legislatures

have not reenacted valid capital-sentencing statutes (Delaware, New York, and Washington). The

District of Columbia also has repealed the death penalty legislatively. In three of the twenty-seven

states that have retained the death penalty, gubernatorial moratoria on executions are in effect. Capital

punishment is authorized under federal law and under United States Military law. See, DEATH

PENALTY INFO. CTR., https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state

[https://perma.cc/4PXZ-6Q6D]. More specific information is provided subsequently about the

jurisdictions that no longer authorize capital punishment. See State by State, infra note 32 and

accompanying text.

11. In Connecticut, for example, the fate of Joshua Komisarjefsky and Steven Hayes, the death-

sentenced murderers of members of the Petit family, loomed as a major point of contention with

respect to abolition efforts in the state. See, e.g., Christina Ng, Family Massacre Survivor William

Petit Opposes Repeal of CT Death Penalty, ABC NEWS (Apr.

4, 2012), https://abcnews.go.com/US/family-massacre-survivor-william-petit-repeal-connecticut-

death/story?id=16072574 [https://perma.cc/S9BM-WEGK]; Mary Ellen Godin, Connecticut Senate

Votes to Repeal Death Penalty in State, REUTERS (Apr. 5, 2012), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-

usa-deathpenalty-connecticut/connecticut-senate-votes-to-repeal-death-pen alty-in-state-

idUSBRE83406N20120405 [https://perma.cc/C4Z8-5UUS].

In New Hampshire, where legislative repeal of the death penalty took effect May 30, 2019, much

debate centered on the fate of the single offender under sentence of death, Michael Addison. See Evan

Allen, As N.H. Considers Repealing the Death Penalty, the Lone Man on Death Row Looms Large,

BOST. GLOBE (May 17, 2019), https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/05/17/considers-repealing-

death-penalty-lone-man-death-row-looms-large/00KkWfffEcsmba4Lmq2cRJ/story.html

[https://perma.cc/BW3C-VLHC].

Similar controversy ensued in Colorado, where three offenders were under sentence of death while

debate about repealing Colorado’s death penalty law unfolded. When Governor Jared Polis signed

repeal legislation on March 23, 2020, he commuted the offenders’ death sentences to life

imprisonment without parole. See Valerie Richardson, ‘Polis Hijacks Justice’: Democrat Loses Fight

4

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 271

controversial. For example, in 2016, California voters were asked to

decide through a ballot initiative whether the state’s death penalty should

be eliminated and replaced with life imprisonment without parole.

12

The

fate of the state’s nearly 750 death row inmates hung in the balance,

13

because the measure was expressly made retroactive.

14

The proposition

narrowly failed,

15

leaving the previously imposed death sentences

undisturbed. At the other end of the death row spectrum, when New

Hampshire repealed its capital punishment law in 2019,

16

the measure’s

prospective application left the death sentence of the lone offender

awaiting execution unaffected.

17

to Keep Son’s Killers on Death Row in Colorado, WASHINGTON TIMES (Mar. 25, 2020),

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/mar/25/jared-polis-colorado-death-penalty-repeal-

blasted-/ [https://perma.cc/CG7J-7893]; Neil Vigdor, Colorado Abolishes Death Penalty and

Commutes Sentences of Death Row Inmates, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 23, 2020),

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/colorado-death-penalty-repeal.html

[https://perma.cc/CEA8-DSAE ]. See Colo. Exec. Orders, infra notes 60 & 61 and accompanying

text.

See also Kevin Barry, From Wolves, Lambs (Part I): The Eighth Amendment Case for Gradual

Abolition of the Death Penalty, 66 FLA. L. REV. 313, 315–25 (2014) [hereinafter Barry I].

12. The full text of the ballot initiative was styled as the Justice That Works Act of 2016 and

presented to the voters in California as Proposition 62. Mike Farrell, Justice That Works Act of 2016,

OFF. OF THE CAL. ATT’Y GEN (Sept. 15, 2015), https://www.oag.ca.gov/system/

files/initiatives/pdfs/15-0066%20%28Death%20Penalty%29.pdf [https://perma.cc/A562-VY78].

13. On October 1, 2016, 745 individuals were under sentence of death in California. See

Deborah Fins, Death Row U.S.A. Fall 2016, NAACP LEGAL DEF. & EDUC. FUND, INC. (Oct. 1, 2016),

1, 39–45, https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/DRUSAFall2016.pdf [https://

perma.cc/4WXU-XQL6].

14. Farrell, supra note 12, provided in part:

SEC. 10. Retroactive Application of Act

(a) In order to best achieve the purpose of this act as stated in Section 3 and to achieve

fairness, equality and uniformity in sentencing, this act shall be applied retroactively.

(b) In any case where a defendant or inmate was sentenced to death prior to the effecti ve

date of this act, the sentence shall automatically be converted to imprisonment in the state

prison for life without the possibility of parole under the terms and conditions of this act.

The State of California shall not carry out any execution following the effective date of

this act. . . .

15. Voters rejected the proposition by a margin of 53.15% to 46.85%. See California

Proposition 62, Repeal of the Death Penalty, BALLOTPEDIA, https://ballotpedia.org/

California_Proposition_62,_Repeal_of_the_Death_Penalty_(2016) [https://perma.cc/5BY2-2FJ5 ];

California Proposition 62 — Repeal Death Penalty — Results: Rejected, N.Y. TIMES (Aug. 1, 2017),

https://www.nytimes.com/elections/2016/results/california-ballot-measure-62-repeal-death -penalty

[https://perma.cc/8QKS-N8M4].

16. N.H. REV. STAT. ANN. § 630:1, III (2019). See infra note 148 and accompanying text.

17. See Mark Berman, New Hampshire Abolishes Death Penalty After Lawmakers Override

Governor, WASH. POST

(May 30, 2019), https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/new-hampshire-will-abandon-deat h-

penalty-after-lawmakers-override-governor/2019/05/30/d0bdec8e-824c-11e9-bce7-

40b4105f7ca0_story.htm [https://perma.cc/T226-3EYD] (noting that the death sentence of Michael

5

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

272 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

When the repeal of capital punishment legislation is under

consideration, not only is the abstract proposition of whether the death

penalty should be abandoned or retained at issue, but also whether the

death sentences lawfully imposed on past offenders for their very real and

often heinous murders—crimes that have claimed the lives of identifiable

victims and irretrievably altered the lives of victims’ survivors

18

—would,

should, or must be rendered nullities and replaced with life

imprisonment.

19

Parsing the moral,

20

legal,

21

political,

22

and

philosophical

23

dimensions of these questions, which must inevitably be

confronted in active death-penalty jurisdictions, is fraught with

complexities. For instance: Would executing offenders under sentence of

death for their previously committed crimes following the repeal of death

penalty legislation continue to be justified (or demanded) in the name of

retribution?

24

Could executing previously sentenced murderers possibly

Addison, the only person under sentence of death in New Hampshire, remained undisturbed, although

Addison did not face imminent execution). See infra notes 150–153 and accompanying text.

18. See generally WOUNDS THAT DO NOT BIND: VICTIM-BASED PERSPECTIVES ON THE

DEATH PENALTY (James R. Acker & David Karp, eds., 2006).

19. “‘When we talk about the death penalty in the abstract, there’s a growing movement toward

abolition because of concerns about fairness, accuracy, discrimination, and cruelty,’ Northeastern

University law professor Daniel Medwed said. ‘But on a granular level, in an individual case, it gets

complicated.’” Allen, supra note 11.

20. See Barry I, supra note 11, at 332–36.

21. Id. at 336–85; see generally Kevin Barry, From Wolves, Lambs (Part II): The Fourteenth

Amendment Case for Gradual Abolition of the Death Penalty, 35 CARDOZO L. REV. 1829 (2014)

[hereinafter Barry II].

22. See Kevin Barry, Going Retro: Abolition for All, 46 LOY. U. CHI. L.J. 669, 674 (2015)

(“The primary reason why states are repealing [death-penalty laws] prospectively only is, not

surprisingly, political.”).

23. Immanuel Kant’s views on capital punishment include the oft-cited passage: “ Even if a

civil society were to dissolve itself by common agreement of all its members (for example, if the

people inhabiting an island decide to separate and disperse themselves around the world), the last

murderer remaining in prison must first be executed, so that everyone will duly receive what his

actions are worth and so that the bloodguilt thereof will not be fixed on the people because they failed

to insist on carrying out the punishment; for if they fail to do so, they may be regarded as accomplices

in this public violation of legal justice.” IMMANUEL KANT, THE METAPHYSICAL ELEMENTS OF

JUSTICE 102 (John Ladd trans. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. 2d ed. 1999). See Don E. Scheid,

Kant’s Retributivism, 93 ETHICS 262, 279 (1983). For other philosophical perspectives on the death

penalty in general, see Tom Sorell, Aggravated Murder and Capital Punishment, 10 J. APPLIED PHIL.

201 (1993); see generally David Heyd, Hobbes on Capital Punishment, 8 HIST. PHIL. Q. 119 (1991).

24. A majority of the Supreme Court in State v. Santiago, 122 A.3d 1 (Conn. 2015) answered

this question in the negative, drawing a contrast between public retribution and private vengeance:

Finally, it bears emphasizing that, to the extent that the statutory history of P.A. 12-5 [the

repealed legislation] reveals anything with respect to the legislature’s purpose in

prospectively abolishing the death penalty while retaining it for the handful of individuals

now on death row, it is that the primary rationale for this dichotomy was neither deterrence

nor retribution but, rather, vengeance—the Hyde to retribution’s Jekyll. Vengeance, unlike

retribution, is personal in nature; it is motivated by emotion, and may even relish in the

6

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 273

have general deterrence value in a post-repeal era, when the death penalty

no longer is a threatened punishment?

25

Would executing offenders under

suffering of the offender. Accordingly, vengeance traditionally has not been considered a

constitutionally permissible justification for criminal sanctions. See Ford v. Wainwright,

477 U.S. 399, 410 (1986) (finding no retributive value in “the barbarity of exacting

mindless vengeance”). On the contrary, ”[i]t is of vital importance to the defendant and to

the community that any decision to impose the death sentence be, and appear to be, based

on reason rather than caprice or emotion.” Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 358 (1977)

(plurality opinion).

There are, no doubt, cases in which the line between a principled commitment to

retributive justice and an impermissible acquiescence to private vengeance is a gray one.

There is every indication, however, that P.A. 12-5 was crafted primarily to maintain the

possibility of executing two particular offenders—the much reviled perpetrators of the

widely publicized 2007 home invasion and murder of three members of Cheshire’s Petit

family.

Id. at 71–72 (citation and footnote omitted). See also id. at 173 (Eveleigh, J., concurring) (“ Vengeance

has no place in the orderly administration of justice by a civilized society. It certainly can never serve

as the justification for the death penalty in today’s world. My review of the text and legislative history

of the public act under consideration, No. 12-5 of the 2012 Public Acts (P.A. 12-5), leads me to the

inescapable conclusion that vengeance was the motivating factor underlying the enactment of the

provisions allowing the eleven men on death row to be executed while eliminating the death penalty

for crimes committed in the future.”). But see Barry I, supra note 21, at 371–73; Robert Blecker,

Death is Only Justice, N.Y. POST (Mar. 30, 2011), https://nypost.com/2011/03/30/death-is-only-

justice [https://perma.cc/3UNE-G53M].

25. Considering this question in State v. Santiago, 122 A.3d 1, 57 (Conn. 2015), the

Connecticut Supreme Court had no difficulty concluding that the death penalty could have no possible

deterrent value following repeal of the capital punishment statute:

Turning first to deterrence, we observe that it is clear that, with the passage of P.A. 12-5

[the repealed legislation], any deterrent value the death penalty may have had no longer

exists. As Justice Harper explained in his dissent in Santiago I: “The ultimate test of this

deterrence claim is whether the state, by executing some of its citizens, better achieves the

unquestionably legitimate goal of discouraging others from committing similar crimes. As

a general matter, the empirical evidence regarding deterrence is inconclusive. Following

the abolition of the death penalty for all future offenses committed in Connecticut,

however, it is possible to determine the exact number of potential crimes that will be

deterred by executing the defendant in this case. That number is zero.” (Emphasis omitted;

footnote omitted.) State v. Santiago, [49 A.3d 566, 700 (Conn. 2012)] (Harper, J.,

concurring in part and dissenting in part).

While conceding that the argument that executing offenders following legislative repeal of the death

penalty would operate as a deterrent for future prospective murderers “is a somewhat harder case”

than finding continuing retributive value, Professor Barry nevertheless has offered an argument:

How, one might ask, can the death penalty deter future offenders if no future offender will

ever be put to death? The answer is that by imposing the death penalty against those

currently on death row, prospective-only repeal “communicate[s] to all criminals that they

will be held to account for their crimes in the manner in which the law provides when they

commit them.” Through prospective-only repeal, the legislature is making absolutely clear

to future offenders that it means what it says-that they should be under no illusion that a

change in law tomorrow will spare them the consequences of their actions today.

Offenders sentenced to death will not benefit from the subsequent repeal of the death

penalty, any more than future offenders sentenced to life in prison without the possibility

of parole (LWOP) will benefit from some yet-to-be-enacted repeal of LWOP down the

7

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

274 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

sentence of death after repeal legislation is enacted heighten the

arbitrariness of capital sentencing practices to impermissible levels, in that

otherwise indistinguishable offenders who commit otherwise

indistinguishable crimes are spared the risk of execution simply because

the death penalty is no longer in effect?

26

Questions of this nature are important and demand attention;

however, the thrust of this Article lies elsewhere. The focus is not on

normative considerations, including the justice or fairness of executing

offenders who are under sentence of death at the time death-penalty

legislation is repealed or invalidated. Nor do we dwell on utilitarian

considerations such as whether measurable costs or benefits of carrying

out executions following repeal or invalidation of the death penalty will

likely ensue. The current objective is more modest. Rather than explore

what should happen, our goal is to document what has happened

historically to offenders who are on death row, awaiting execution, at the

time capital punishment laws are repealed or judicially invalidated. In

addition to embodying the political, ethical, and prudential judgments

made over time, past practices regarding whether executions have been

carried out in jurisdictions after sentences of death are no longer

road. “ Future offenders beware,” the legislature is saying. “You get what we say you get,

not what we say as modified by what we haven’t said yet (in future legislation).”

Barry I, supra note 11, at 373–74 (footnotes and citation omitted).

26. See State v. Santiago, 122 A.3d 1, 128 (Conn. 2015) (Eveleigh, J., concurring):

[T]he arbitrariness in the present case stems from the effective date provision of the act,

which, in effect, renders the date on which a defendant commits his crime an eligibility

factor for the death penalty. I fail to see how this scheme, which permits the imposition of

the death penalty for a capital felony committed at any time prior to 11:59 p.m. on April

24, 2012, but rejects categorically the imposition of the death penalty for the same conduct

or even substantially more heinous acts carried out two minutes later, is in any way distinct

from the constitutionally infirm schemes rejected by the United States Supreme Court in

Furman [v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972)]. The circumstances that I describe strike me as

exactly the sort of wanton and freakish imposition of the death penalty that runs afoul of

the eighth amendment of the United States constitution.

See also id. at 111–12. But see Barry I, supra note 11, at 381–82 (footnote omitted):

Because the legislature’s decision to repeal a law has nothing to do with a jury’s decision

to sentence a person to death, and has everything to do with the separation of powers

between the judicial and legislative branches, Furman is inapplicable to prospective-only

repeal. As the Court in Gregg [v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 195 (1976) (plurality opinion)]

made clear, if “the sentencing authority is apprised of the information relevant to the

imposition of [a] sentence and provided with standards to guide its use of the information,”

the risk of an arbitrary and capricious sentence in violation of the Eighth Amendment is

removed. The sentence does not suddenly become arbitrary and capricious because the

legislature decides to repeal the death penalty prospective-only at some later date. In short,

Furman concerns whether a jury’s sentence of death was arbitrary and capricious, not

whether a state’s eventually carrying out that sentence might be.

See generally id. at 378–83.

8

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 275

authorized are directly relevant to the Supreme Court’s determination of

whether, as applied, the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment’s

prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments.

Perhaps surprisingly, death-penalty repeals, and occasionally cycles

of repeal and reinstatement, have occurred with some frequency over

time, and in many jurisdictions. Ascertaining what has happened

historically to offenders awaiting execution at the time capital punishment

laws have been repealed or invalidated is of immediate interest to one

aspect of the Supreme Court’s death penalty jurisprudence. While giving

content to the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual

punishments, the justices have consistently “been guided by ‘objective

indicia,’ . . . [including] state practice with respect to executions,”

27

to

help determine whether capital punishment policies are consistent with

“the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing

society.”

28

The initial section of this Article examines jurisdictions within the

United States that have transitioned from authorizing capital punishment

to abandoning it, either temporarily or permanently, to determine whether

offenders who were under sentence of death at the time of legislative

repeal or judicial invalidation have been executed.

29

The next section

27. Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407, 421 (2008) (quoting Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S.

551, 563 (2005)).

28. Chief Justice Warren’s plurality opinion in Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 101 (1958),

observed that “[t]he [Eighth] Amendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” The plurality opinion in Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153, 173 (1976), endorsed this principle while rejecting the argument that the Eighth

Amendment prohibits capital punishment for aggravated murder. In doing so, the justices relied in

part on juries’ sentencing practices, noting that “the actions of juries in many States since Furman [v.

Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972)] are fully compatible with the legislative judgments, reflected in the

new statutes, as to the continued utility and necessity of capital punishment in appropriate cases. At

the close of 1974 at least 254 persons had been sentenced to death since Furman, and by the end of

March 1976, more than 460 persons were subject to death sentences.” Id. at 182 (plurality opinion).

In later cases, the justices have looked to execution practices while resolving Eighth Amendment

challenges in contexts including whether capital punishment is permissible for the crime of raping an

adult (Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584, 596–97 (1977) (plurality opinion)) or a child (Kennedy v.

Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407, 433–34 (2008)); for juvenile offenders (Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S.

815, 832–33 (1988) (plurality opinion); Id. at 852–53 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the judgment);

Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361, 373–74 (1989); Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551, 564–65

(2005)); for intellectually disabled offenders (Atkins v. Virginia, 534 U.S. 304, 316 (2002)); and for

offenders convicted of felony murder who did not personally kill their victim (Enmund v. Florida,

458 U.S. 782, 794–95 (1982)).

29. The information provided in this section relies in part on the Brief of Amici Curiae, Legal

Historians & Scholars, Connecticut v. Santiago, 305 Conn. (filed Dec. 2, 2012). Brian W. Stull

authored this brief, with the assistance of Alex V. Hernandez. The Legal Historians and Scholars

supporting the brief included Professors James R. Acker, Stuart Banner, William J. Bowers, Dr. Scott

Christianson, David Garland, James S. Liebman, Michael Meltsner, Richard Moran, Michael L.

9

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

276 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

offers analogous information about international practices, with specific

attention given to the Canadian and British experiences. The last section

explores whether any 16- or 17-year-old offenders were executed in states

that raised the minimum age of death-penalty eligibility to 18 after their

death sentences were imposed, but before the Supreme Court ruled in

2005 that the Eighth Amendment prohibits the capital punishment of

offenders younger than 18.

30

In short, these investigations have uncovered no cases in which

executions have gone forward under those circumstances.

II. H

IST ORICAL PRACTICES IN THE UNITED STATES

Several jurisdictions within the United States have abandoned capital

punishment, either permanently or temporarily, following a period when

death-penalty laws were in effect and utilized. We first identify those

jurisdictions and the years in which they did and did not authorize capital

punishment. We then summarize the execution practices in those

jurisdictions during the times that their death-penalty laws were no longer

in effect.

A. American Jurisdictions Which Have Repealed or Judicially

Invalidated their Death-Penalty Laws

The following American jurisdictions do not currently authorize

capital punishment because they have repealed or courts have invalidated

their death-penalty laws:

Alaska (repeal March 30, 1957)

Colorado (repeal July 1, 2020)

Connecticut (repeal April 25, 2012)

Delaware (judicial invalidation Aug. 2, 2016)

District of Columbia (repeal Feb. 26, 1981)

Hawaii (repeal June 5, 1957)

Radelet, Austin Sarat, and Franklin E. Zimring. In State v. Santiago, 122 A.3d 1 (Conn. 2015), the

Connecticut Supreme Court invalidated Connecticut’s death penalty on state constitutional grounds

and also invalidated the sentences of all offenders then on the state’s death row. See also M. Watt

Espy & John Ortiz Smykla, Executions in the United States, 1608-2002: The Espy File, INTER-U.

CONSORTIUM FOR POL. & SOC. RES. (Jul. 20, 2016), https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/

icpsrweb/NACJD/studies/8451 [https://perma.cc/Q8XA-Q97W] [hereinafter ICPSR: The Espy File];

M. Watt Espy, M. Watt Espy Papers, 1730-2008, U. AT ALB., NAT’L DEATH PENALTY ARCHIVE,

https://archives.albany.edu/description/catalog/apap301 [https://perma.cc/DLS2-HRVQ]; DEATH

PENALTY INFO. CTR. (Dec. 16, 2020), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/ [https://perma.cc/JRG3-P4CK].

30. Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005).

10

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 277

Illinois (repeal July 1, 2011)

Iowa (repeal July 4, 1965)

Maine (repeal March 17, 1887)

Maryland (repeal Oct. 1, 2013)

Massachusetts (judicial invalidation Oct. 18, 1984)

Michigan (repeal March 1, 1847)

Minnesota (repeal April 22, 1911)

New Hampshire (repeal May 30, 2019)

New Jersey (repeal Dec. 17, 2007)

New Mexico (repeal July 1, 2009)

New York (judicial invalidation Oct. 23, 2007)

North Dakota (repeal March 19, 1915)

Rhode Island (repeal Feb. 11, 1852)

31

Vermont (repeal Apr. 15, 1965)

Virginia (repeal July 1, 2021)

Washington (judicial invalidation Oct. 11, 2018)

West Virginia (repeal June 18, 1965)

Wisconsin (repeal July 12, 1853)

32

The following states repealed capital punishment laws in the pre-

Furman

33

era and later reinstated them:

Arizona (repeal Dec. 8, 1916, reinstated Dec. 5, 1918)

Colorado (repeal June 29, 1897, reinstated July 31, 1901)

Delaware (repeal Apr. 2, 1958, reinstated Dec. 18, 1961)

Iowa (repeal May 1, 1872, reinstated May 26, 1878)

Kansas (repeal Jan. 30, 1907, reinstated March 11, 1935)

Maine (repeal Feb. 21, 1876, reinstated March 13, 1883)

Missouri (repeal Apr. 13, 1917, reinstated July 8, 1919)

New Mexico (partial repeal March 31, 1969, reinstated March 30,

1979)

New York (partial repeal June 1, 1965, reinstated March 7, 1995)

31. Following its repeal of the death penalty in 1852, the Rhode Island legislature reinstated

capital punishment for murder committed by a life-term prisoner in 1872. That provision was never

used and was rendered unconstitutional by virtue of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972). Legislation was enacted in 1973 which mandated capital punishment for murder

committed by a prisoner. This provision was ruled unconstitutional in 1979. See infra note 211 and

accompanying text.

32. Considerable information about state death-penalty laws and practice is available at State

by State, DEATH PENALTY INFO. CTR., https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-

state [https://perma.cc/98UX-2FUZ].

33. Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

11

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

278 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

Oregon (repeal Dec. 3, 1914, reinstated May 21, 1920; repeal Nov.

30, 1964, reinstated Dec. 7, 1978)

South Dakota (repeal Feb. 15, 1915, reinstated Jan. 27, 1939)

Tennessee (partial repeal March 27, 1915, (for murder, but not for

rape or for murder committed by life term prisoner), reinstated for murder

Jan. 27, 1919)

Washington (repeal March 22, 1913, reinstated March 14, 1919)

34

B. Execution Practices in Jurisdictions Following Legislative Repeal

or Judicial Invalidation of Death-Penalty Statutes

The execution practices within jurisdictions that have legislatively

repealed or judicially invalidated their capital punishment laws are

detailed below.

1. Alaska

Legislative repeal March 30, 1957

No executions following 1957 repeal

Twelve executions were carried out in Alaska during its territorial

days,

35

the first in 1869 and the last on April 4, 1950.

36

The Alaska

Territorial Legislature abolished capital punishment in 1957, enacting a

measure which stated: “The death penalty is and shall hereafter be

abolished as punishment in Alaska for the commission of any crime.”

37

34. State by State, supra note 32.

35. Alaska became a state in 1959 and entered the union as the 49th state on January 3, 1959.

Alaska’s History, ALASKA PUB. LANDS INFO. CENTS., https://www.alaskacenters.gov/explore/

culture/history [https://perma.cc/H9NC-WJUL].

36. ICPSR: The Espy File, supra note 29, at Alaska, V16(2), V14. The last person executed in

Alaska was Eugene LaMoore, who was hanged April 14, 1950. Id. See also JOHN F. GALLIHER,

LARRY W. KOCH, DAVID PATRICK KEYS & TERESA J. GUESS, AMERICA WITHOUT THE DEATH

PENALTY: STATES LEADING THE WAY 123 (Northeastern U. Press 2002); Executions in the U.S. 1608-

2002: The ESPY File Executions by State, DEATH PENALTY INFORMATION CENTER 1,

https://files.deathpenaltyinfo.org/legacy/documents/ESPYstate.pdf [https://perma.cc/UJM5-7MPU]

[hereinafter “DPIC, Executions in the U.S.”]; Melissa S. Green, The Death Penalty in Alaska, 25

ALASKA JUST. F. 11 (2009).

37. Green, supra note 36; Averil Lerman, Capital Punishment in Territorial Alaska: The Last

Three Executions, 9 FRAME OF REFERENCE 6, 16–19 (1998); GALLIHER ET AL., supra note 36, at 124

& n. 34 (citing Territory of Alaska: Session Laws, Resolutions, and Memorials, Laws of Alaska (30

March 1957), ch. 132, at 263).

12

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 279

Capital punishment has not been authorized since,

38

and no executions

were conducted in the state after 1950, including the post-repeal period.

39

2. Arizona

Legislative repeal Dec. 8, 1916

No executions following repeal through reinstatement

Legislative reinstatement Dec. 5, 1918

First post-repeal execution April 16, 1920

The last of three executions conducted in Arizona in 1916 took place

when Miguel Peralta was hanged on July 7.

40

Almost exactly five months

later, on December 8, 1916, a voter initiative became effective which

abolished the state’s death penalty.

41

The state reenacted death-penalty

legislation through a referendum just two years later, with reinstatement

38. State by State, supra note 32 (identifying Alaska as a state without the death penalty);

Thompson v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 815, 826 n. 25 (1988) (plurality opinion) (identifying Alaska as a

state that does not authorize capital punishment, and citing Territory of Alaska, Session Laws, 1957,

ch. 132, 23d Sess., an Act abolishing the death penalty for the commission of any crime; see ALASKA

STAT. ANN. § 12.55.015 (West 1987) (“Authorized sentences” do not include the death penalty; §

12.55.125, Sentences of imprisonment for felonies” do not include the death penalty). ALASKA STAT.

ANN. § 12.55.015 (1987) (“Authorized sentences” do not include the death penalty; § 12.55.125,

“Sentences of imprisonment for felonies” do not include the death penalty).

39. See Execution Database (Alaska), DEATH PENALTY INFO. CENT.,

https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/executions/execution-database?filters%5Bstate%5D=Alaska

[https://perma.cc/5AJ6-36BS] (no executions in Alaska in database chronicling executions in the

United States 1977 to present); Green, supra note 36.

40. DPIC, Executions in the U.S., supra note 36, at 39; Executions Prior to 1992 & Execution

Methods, ARIZ. DEPT. OF CORRECTIONS, https://corrections.az.gov/public-resources/deat h-

row/executions-prior-1992-execution-methods [https://perma.cc/XQ6S-J446]. See also ICPSR: The

Espy File, supra note 29, at Arizona, V16(4), V14.

41. Arizona Death Penalty History, ARIZ. DEPT. OF CORR., https://corrections.az.gov/public-

resources/death-row/arizona-death-penalty-history [https://perma.cc/65WZ-X64K]; John F. Galliher,

Gregory Ray, & Brent Cook, Abolition and Reinstatement of Capital Punishment During the

Progressive Era and Early 20

th

Century, 83 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 538, 552 (1992). See Ex

parte Faltin, 254 P. 477, 478 (Ariz. 1927) (quoting the initiative measure:

Be it enacted by the people of the state of Arizona:

Section 1. That paragraph 173, chapter I, title VIII, Penal Code, of the Revised Statutes of

Arizona, 1913 [authorizing punishment of death for murder in the first degree], be and the

same is hereby amended so as to read as follows:

173. Every person guilty of murder in the first degree shall suffer imprisonment for life,

and every person guilty of murder in the second degree shall be confined in the State Prison

for not less than ten years. No person convicted of the crime of murder shall be

recommended for pardon, commutation or parole by the board of pardons and paroles

except upon newly discovered evidence establishing to the satisfaction of all the members

of said board his or her innocence of the crime for which conviction was secured.

Sec. 2. All acts and parts of acts in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.).

13

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

280 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

taking effect December 5, 1918.

42

The first post-repeal execution occurred

April 16, 1920, when Simplicio Torrez was hanged for a murder

committed May 1, 1919.

43

In January 1917, the Arizona Pardon Board

commuted the sentences of prisoners who were on death row when the

repeal legislation became effective.

44

One inmate, William Faltin, had

been sentenced to death in 1913 for a murder committed in 1912. He was

found “insane,” or incompetent for execution, in December 1915 and

retained that status when the repeal legislation went into effect in

December 1916. He was certified as “sane” in August 1917, and remained

in prison at the time he sought release in 1927 through a writ of habeas

corpus. In denying his release, the Arizona Supreme Court further

declined to invalidate his death sentence or rule that a sentence of life

imprisonment should be substituted. The court reasoned that the repeal

legislation had not invalidated the death sentence originally imposed in

1913, and that because the death penalty had been reinstated in 1918, there

42. The reinstatement measure restored the law as it existed prior to repeal, and provided:

“Every person guilty of murder in the first degree shall suffer death or imprisonment in the territorial

prison for life, at the discretion of the jury trying the same, or, upon the plea of guilty, the court shall

determine the same; and every person guilty of murder in the second degree is punishable by

imprisonment in the territorial prison not less than ten years.” Ex parte Faltin, 254 P. 477, 477 (Ariz.

1927) (quoting the initiative measure and prior legislation); Arizona Death Penalty History, supra

note 41.

The short period of abolition was decisively repudiated by the voters, a result apparently fueled in

part by highly publicized killings committed by individuals who purportedly boasted that without a

death penalty they could commit murder without being unduly concerned about the consequences.

Galliher, et al., supra note 41, at 562–64.

43. Executions Prior to 1992 & Execution Methods, ARIZ. DEPT. OF CORR.,

https://corrections.az.gov/public-resources/death-row/executions-prior-1992-execution-methods

[https://perma.cc/XB27-63TN]; Documentation for the Execution of Simplicio Torrez, 1920-04-16,

U. ALBANY NAT’L DEATH PENALTY ARCHIVE, https://archives.albany.edu/concern/

daos/gb19fd98m?locale=en#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-2081%2C1203%2C7573%2C4868

[https://perma.cc/MNG9-X9X5] [hereinafter DEATH PENALTY ARCHIVE].

44. Shortly after repeal of Arizona’s death penalty law, in 1917, the Arizona Pardon Board

commuted the death sentences of prisoners remaining on death row. Arizona’s Death Penalty: A

Chronological History, ARIZONA SHERIFF, Mar. 1977 (reproducing prior news articles, including

Hangings Abolished, PHOENIX MESSENGER, Jan. 13, 1917 (noting commutations)).

The Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry, maintains an Historical Prison

Register. Historical Prison Register, THE ARIZ. DEP’T OF CORRS., REHAB. & REENTRY (2020),

https://corrections.az.gov/historical-prison-register-d#Bac-El-Cle [https://perma.cc/RY7B-FM35]

((A-D) and thereafter for surnames (E-I, J-L, M-S, and T-Z)). The records indicate when prisoners

were received on death row and when and how they left death row. Inspection of those records reveals

no inmates who were received on death row before the repeal legislation went into effect on Dec. 6,

1916 were executed thereafter; all were subsequently released, died in prison, or no release date is

indicated.

14

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 281

existed no barrier to carrying it out.

45

The following year, in 1928, Faltin’s

sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

46

In 2019, Arizona’s capital sentencing law was amended by removing

three aggravating factors from prior law that designated what types of

murder were death-penalty eligible, and narrowing a fourth aggravating

factor.

47

The full extent of the consequences of this narrowing are

currently unknown, but, in a ruling likely to be reviewed by the Arizona

Supreme Court, a trial court has recently vacated a death sentence

supported only by an aggravating circumstance that no longer exists.

48

45. Ex parte Faltin, 254 P. 477, 477 (Ariz. 1927).

46. Faltin’s death sentence was commuted to life and he died of natural causes in prison. Life

Termers Skip in the Night, PRESCOTT EVENING COURIER, Dec. 28, 1939, at 1, 8 (“ In 1928, [Faltin’s

death] sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the parole board.”). See also Historical Prison

Register [E–I], THE ARIZ. DEP’T OF CORRS., REHAB. & REENTRY (2020),

https://corrections.az.gov/historical-prison-register-e-i [https://perma.cc/BJD4-D5RB] (indicating

that William Faltin was received in prison Apr. 15, 1913, and remained confined until he died Jan.

15, 1953).

47. The aggravating factors making murder death penalty-eligible under current Arizona law

are itemized in ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 13-751 (F) (LexisNexis 2019). The three aggravating facto rs

eliminated from prior law, ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 13-751 (F) (LexisNexis 2012) are (F)(3) “In the

commission of the offense the defendant knowingly created a grave risk of death to another person or

persons in addition to the person murdered during the commission of the offense,” (F)(13) “The

offense was committed in a cold, calculated manner without pretense of moral or legal justification,”

and (F)(14) “The defendant used a remote stun gun or an authorized remote stun gun in the

commission of the offense.” See Dillon Rosenblatt, GOP Bill Scales Back Death Penalty Eligibility,

ARIZ. CAPITOL TIMES (Feb. 22, 2019), https://azcapitoltimes.com/news/2019/02/22/gop-bill-scales-

back-death-penalty-eligibility/ [https://perma.cc/DG3G-NSXP] (“Dale Baich, who heads the capital

habeas unit of the Federal Public Defender’s Office in Arizona, said the latter two aggravators are

used very infrequently, which is why the bill would eliminate them; the first is used more often.”). In

addition to eliminating these three aggravating factors, the legislation substantially narrowed the

“pecuniary gain” aggravating circumstance under (F)(5), making it now applicable only in “ murder-

for-hire” circumstances. Compare ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 13-751 (F) (5) (LexisNexis 2012) (“ T he

defendant committed the offense as consideration for the receipt, or in expectation of the receipt, of

anything of pecuniary value.”) with ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 13-751 (F) (3) (LexisNexis 2019) (“T he

defendant procured the commission of the offense by payment or promise of payment, of anything of

pecuniary value, or the defendant committed the offense as a result of payment, or a promise of

payment, of anything of pecuniary value.”).

48. In State v. Greene, Order, No. CR-21-0082-PC (Pima Co. Sup. Ct. Feb. 2, 2021), a superior

court judge vacated the death sentence of Beau John Greene. This was because Greene’s death

sentence had only been supported by the former pecuniary-value aggravator set out in ARIZ. REV.

STAT. § 13-751 (F) (5) (LexisNexis 2012), but was not factually supported under the narrowed version

of the aggravator that contemplates murder-for-hire scenarios. The State of Arizona has petitioned the

Arizona Supreme Court to review this lower-court decision. See State’s Pet. For Review, State v.

Greene, 2021 WL 2368153 (March 4, 2021). Greene had originally been sentenced to death based on

an additional aggravating factor – that his killing was especially heinous, cruel, or depraved. State v.

Greene, 967 P.2d 106, 114–116 (Ariz. 1998). The Arizona Supreme Court, however, found the

evidence of that aggravator insufficient. Id. One reason the consequences and reach of the 2019

narrowing remains uncertain is that in many cases, unlike Greene’s, additional still-valid aggravating

circumstances will remain.

15

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

282 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

3. Colorado

Legislative repeal June 29, 1897

No executions following repeal through legislative reinstatement

Legislative reinstatement July 31, 1901

First post-repeal execution March 6, 1905

Legislative repeal July 1, 2020

The last three executions conducted in Colorado prior to the State’s

1897 repeal of its death-penalty law took place on the same day, June 26,

1896.

49

Governor Alva Adams signed the repeal bill March 29, 1897 and

the legislation became effective 90 days later, on June 29. The statute

abolishing capital punishment and providing for life imprisonment for

murder was explicitly prospective in its terms. It provided that, “Any

murder which shall have been committed before this Act takes effect shall

be inquired of, prosecuted, and punished in accordance with the law in

force at the time such murder was committed.”

50

Governor Adams,

however, commuted the death sentences of five men who, though

sentenced to death very near the time of the repeal (either before or after),

were not protected by the repeal because their crimes took place before it

went into effect. Thus, in April 1897, after the repeal bill was signed but

before the legislation took effect, he commuted the death sentences of two

men convicted of murder and sentenced to death in 1896.

51

Another

offender committed murder in April 1897 and was convicted and

sentenced to death in June,

52

while two others killed their victim in 1896

and were convicted and sentenced to death in September 1897.

53

Governor Adams’ commutations ensured that neither those who

committed a capital crime before the repeal became effective nor those

sentenced to death under prior law would be executed after the repeal

legislation took effect.

54

Colorado reinstated capital punishment on July

49. DPIC, Executions in the U.S., supra note 36 (executions of William Holt, Albert Noble,

and Deonecio Romero); MICHAEL L. RADELET, THE HISTORY OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN COLORADO

202–03 (U. Press of Colorado 2017).

50. RADELET, supra note 49, at 42 (quoting 1897 Colo. Sess. Laws ch. 35).

51. Id. at 252 (discussing cases of Walter Davis and Allen Hense (or Hence) Downen).

52. Id. at 253 (discussing case of John (Jack) Cox).

53. Id. at 252–53 (discussing cases of Jose M. (J.M.) Lucero and Juan Duran).

54. Id. at 42–43 (“Three men were sentenced to death . . . in 1897 for murder that predated

June 29, 1897—after the death penalty abolition bill was signed but before it took effect. . . . Governor

Adams subsequently commuted all three death sentences.”).

16

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 283

31, 1901.

55

The first execution carried out under the reinstituted death-

penalty law did not occur until March 6, 1905, when Azel Galbraith was

hanged for a murder committed in 1904.

56

Colorado’s contemporary, post-Furman

57

death-penalty law was

repealed effective July 1, 2020 by virtue of a bill passed by the legislature

and signed by Governor Jared Polis on March 23, 2020.

58

The repeal was

explicitly prospective:

For offens es charged on or after July 1, 2020, the death penalty is not a

sentencing option for a defendant convicted of a Class 1 Felony in the

State of Colorado. Nothing in this section commutes or alters the sen-

tence of a defendant convicted of an offense charged prior to July 1,

2020. This section does not apply to a person currently serving a sen-

tence of death. Any death sentence in effect July 1, 2020 is valid.

59

Three individuals were under sentence of death when the repeal bill was

signed.

60

On March 23, 2020, Governor Polis commuted the death

sentences of all three men to life imprisonment without the possibility of

parole. The governor explained that his commutation decision in each

case was

. . . consistent with the abolition of the death penalty in the State of Col-

orado, and consistent with the recognition that the death penalty cannot

be, and never has been, administered equitably in the State of Colo-

rado. . . . My decision today is not a commentary on the moral or ethical

implications of the death penalty in our society; rather it is a reflection

of current law in Colorado, where the death penalty has been abol-

ished.

61

55. Michael L. Radelet, Capital Punishment in Colorado: 1859-1972, 74 U. COLO. L. REV.

885, 912 n.121 (2003) (citing 1901 Colo. Sess. Laws 153–54). See also Galliher, et al., supra note

41, at 560.

56. RADELET, supra note 49, at 203; DPIC, Executions in the U.S., supra note 36; DEATH

PENALTY ARCHIVE, Documentation for the Execution of Azel Galbraith, 1905-03-06,

https://archives.albany.edu/concern/daos/dj52wd72h#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-425%2C-

119%2C4930%2C3169 [https://perma.cc/Y4XH-ZCKU].

57. Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

58. S. B.20-100 (Colo. 2020); see COLO. REV. STAT. § 16-11-901 (2020).

59. S.B. 20-100 (Colo. 2020), supra note 58, § 1.

60. See Neil Vigdor, Colorado Abolishes Death Penalty and Commutes Sentences of Death

Row Inmates, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 23, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/colorado-death-

penalty-repeal.html [https://perma.cc/3FFY-9ZDQ] (The 3 offenders whose death sentences were

commuted were Robert Ray, Sir Mario Owens, and Nathan Dunlap).

61. Colo. Exec. Order No. C 2020 001 (Mar. 23, 2020),

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1JxREHjhuS2VvZ3z6XK__btHIn5rHSQil

[https://perma.cc/8QKJ-3QPJ] for Commutation of Sentence (offender 89148) [Nathan Dunlap];

Colo. Exec. Order, No. C 2020 002 (Mar. 23, 2020), https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/

17

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

284 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

In related decisions, the prosecutors in two capital trials that were

underway when the repeal bill was signed withdrew their pursuit of death

sentences, citing the governor’s decision to commute the capital sentences

of the three offenders on death row.

62

4. Connecticut

Legislative repeal April 25, 2012

Judicial invalidation of death penalty on state constitutional grounds

August 25, 2015, removing death sentences of all on death row

No post-repeal executions

Connecticut’s death penalty was repealed by legislation enacted on

April 25, 2012. The repeal was explicitly made prospective, applying only

to crimes committed on or after the statute’s enactment date.

63

Eleven

1JxREHjhuS2VvZ3z6XK__btHIn5rHSQil [https://perma.cc/8QKJ-3QPJ] for Commutation of

Sentence (offender 135951) [Sir Mario Owens]; Colo. Exec. Order No. C 2020 003 (Mar. 23, 2020),

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1JxREHjhuS2VvZ3z6XK__btHIn5rHSQil

[https://perma.cc/8QKJ-3QPJ] for Commutation of Sentence (offender 133752) [Robert Ray].

62. Conor McCormick Cavanagh, Prosecutors Drop Death Penalty Possibility in Adams

County Case, WESTWORD (Mar. 30, 2020), https://www.westword.com/news/prosecutors-drop-

possible-death-penalty-sentence-in-dearing-case-11678065 [https://perma.cc/G9MT-

MG63](quoting District Attorney Dave Young, regarding the murder trial of Dreion Dearing); Shelly

Bradbury, Death Penalty Dropped in Colorado’s Last Pending Capital Case, DENVER POST (Apr.

14, 2020), https://www.denverpost.com/2020/04/14/colorado-springs-murder-death-penalt y-

coronado-shooting/ [https://perma.cc/P8FD-2TBT] (concerning the murder trial of Marco Garcia-

Bravo).

63. See CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 53a-35a (West 2013):

Imprisonment for felony committed on or after July 1, 1981. Definite sentence. Authorized

term.

(1)(A) For a capital felony committed prior to April 25, 2012, under the provisions of

section 53a-54b in effect prior to April 25, 2012, a term of life imprisonment without the

possibility of release unless a sentence of death is imposed in accordance with section 53a-

46a, or (B) for the class A felony of murder with special circumstances committed on or

after April 25, 2012, under the provisions of section 53a-54b in effect on or after April 25,

2012, a term of life imprisonment without the possibility of release . . . .

CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 53a-45 (West 2012) Murder: Penalty; waiver of jury trial;

finding of lesser degree.

(a) Murder is punishable as a class A felony in accordance with subdivision (2) of section

53a-35a unless it is a capital felony committed prior to April 25, 2012, punishable in

accordance with subparagraph (A) of subdivision (1) of section 53a-35a, murder with

special circumstances committed on or after April 25, 2012, punishable as a class A felony

in accordance with subparagraph (B) of subdivision (1) of section 53a-35a, or murder

under section 53a-54d.

CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 53a-54e (West 2012) Construction of statutes re capital felony

committed prior to April 25, 2012.

18

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 285

individuals were under sentence of death in the state when the repeal

legislation became effective.

64

All of their sentences were vacated and

replaced with sentences of life imprisonment without parole after the

Connecticut Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling in State v. Santiago that capital

punishment violated the state constitution.

65

The decision specifically

held that offenders under sentence of death prior to the repeal statute’s

taking effect could not be executed and that the legislature’s directive that

abolition of the death penalty was prospective only was constitutionally

invalid.

66

Connecticut’s last execution was carried out May 13, 2005.

67

No executions were conducted following the 2012 legislative repeal of the

state’s capital punishment law.

68

The provisions of subsection (t) of section 1-1 and section 54-194 shall apply and be given

full force and effect with respect to a capital felony committed prior to April 25, 2012,

under the provisions of section 53a-54b in effect prior to April 25, 2012.

64. See Death Row U.S.A., NAACP LEGAL DEF. & EDUC. FUND, INC.,

https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/DRUSA_Summer_2012.pdf [https://perma.cc/Q6CR-

P4DV] (Page 47 indicates that 11 individuals were under sentence of death in Connecticut on July 1,

2012); Death Row U.S.A., NAACP LEGAL DEF. & EDUC. FUND, INC., https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-

content/uploads/DRUSA_Spring_2012.pdf [https://perma.cc/UUX3-7C5B] (Page 48 indicates that

the same 11 individuals under sentence of death in Connecticut on April 1, 2012). The 11 offenders

then under sentence of death in Connecticut were Lazale Ashby, Robert Breton, Jessie Campbell,

Sedrick Cobb, Steven Hayes, Joshua Komisarjevsky, Russell Peeler, Richard Reynolds, Todd Rizzo,

Eduardo Santiago, Jr., and Daniel Webb. Id.

65. State v. Santiago, 122 A.3d 1 (Conn. 2015). The Connecticut Supreme Court reaffirmed

this decision in State v. Peeler, 140 A.3d 811 (Conn. 2016).

66. State v. Santiago, 122 A.3d 1, 9 (Conn. 2015) (“[W]e are persuaded that following its

prospective abolition, this state’s death penalty no longer comports with contemporary standards of

decency and no longer serves any legitimate penological purpose. For these reasons execution of those

offenders who committed capital felonies prior to April 25, 2012, would violate the state

constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.”). In a concurring opinion, and

relying on the Eighth Amendment as well as the Connecticut Constitution, Justice Eveleigh cited and

discussed several federal and other state court rulings and historical practices supporting the

conclusion that offenders under sentence of death at the time death penalty laws were repealed or

significantly restricted could not thereafter be lawfully executed. Id. at 177–95. But see Barry I, supra

note 11, at 344–52 (citing and discussing decisions in which courts have declined to give retroactive

effect to changes in death-penalty laws). See also id. at 352–57, 374–78 (citing and discussing court

decisions that have given retroactive application to changes in death-penalty laws).

67. Michael Ross waived further judicial review of his capital conviction and sentence, and on

May 13, 2005 was the last person to be executed in Connecticut. See State v. Ross, 849 A.2d 648

(Conn. 2004); Caycie D. Bradford, Waiting to Die, Dying to Live: An Account of the Death Row

Phenomenon from a Legal Viewpoint, 5 INTERDISC J. HUM. RTS L. 77, 83 (2011); Executions

Database (filter Connecticut), DEATH PENALTY INFOR. CTR,

https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/executions/execution-database?filters%5Bstate%5D=Connecticut

[https://perma.cc/WF7M-5STQ].

68. DPIC, supra note 67.

19

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

286 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

5. Delaware

Legislative repeal April 2, 1958

No executions post-repeal to reinstatement

Reinstatement December 18, 1961

Judicial invalidation August 2, 2016

No executions following invalidation

Delaware repealed its death-penalty law on April 2, 1958.

69

Capital

punishment legislation was reenacted three years later, on December 18,

1961.

70

The last execution in the state prior to the 1958 repeal took place

in 1946.

71

The next did not occur until well after reinstatement, in the

modern death penalty era, in 1992.

72

Delaware carried out its last

execution on April 4, 2012.

73

Four years later, on August 2, 2016, the

Delaware Supreme Court invalidated the state’s death-penalty law in Rauf

v. State,

74

ruling that the sentencing provisions violated the Sixth

Amendment right to trial by jury.

75

This decision was given retroactive

effect,

76

thus invalidating the death sentences of the 17 individuals then

on the state’s death row.

77

No executions were carried out following the

69. See Death Row, DEL. DEP’T. CORRECTIONS, https://doc.delaware.gov/views/

deathrow.blade.shtml [https://perma.cc/QDW3-4DV3]; 51 Del. Laws 742 (1958).

70. Death Row, supra note 69 (In 1961, “[t]he Delaware Legislature passed a bill reinstating

the death penalty, but Governor Elbert N. Carvel vetoed the bill on December 12. However, both the

Senate and House overrode the veto, so on December 18 the death penalty was reinstated.”); 53 Del.

Laws 801 (1961).

71. Forrest Sturdivant was executed May 10, 1946. DPIC, Executions in the U.S., supra note

36.

72. Steven Brian Pennell was executed March 14, 1992. Id. See Death Row Executions, DEL.

DEP’T. CORR., https://doc.delaware.gov/views/executions.blade.shtml [https://perma.cc/7NP3-

A2B7].

73. Death Row Executions supra note 72 (execution of Shannon Johnson, April 20, 2012);

Execution Database (Delaware), DEATH PENALTY INFO. CTR., https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/

executions/execution-database?filters%5Bstate%5D=Delaware [https://perma.cc/MD2E-7YY4].

74. Rauf v. State, 145 A.3d 430 (Del. 2016) (per curiam).

75. In making its decision, the Delaware Supreme Court relied on the United States Supreme

Court’s decision in Hurst v. Florida, 136 S.Ct. 616 (2016). See Rauf v. State, 145 A.3d 430, 433 (Del

2016) (per curiam) (“[T]he majority’s collective view [is] that Delaware’s current death penalty

statute violates the Sixth Amendment role of the jury as set forth in Hurst.”). See generally Sheri

Lynn Johnson, John H. Blume, Theodore Eisenberg, Valerie P. Hans & Martin T. Wells, The

Delaware Death Penalty: An Empirical Study, 97 IOWA L. REV. 1925, 1929–31 (2012) (describing

the evolution of Delaware’s capital-sentencing provisions, including the legislative decision in 1991

to replace jury sentencing with judge sentencing).

76. Powell v. State, 153 A.3d 69 (Del. 2016) (per curiam).

77. Id. See Death Row U.S.A., NAACP LEGAL Def. & EDUC. FUND, INC.,

https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/DRUSAFall2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/225L-BRJS]

(as of Oct. 1, 2016, 17 individuals were under sentence of death in Delaware); Esteban Parra,

Delaware’s Last Two Death Row Inmates Sentenced to Life In Prison, DEL. ONLINE (Mar. 13, 2018),

20

Akron Law Review, Vol. 54 [2021], Iss. 2, Art. 3

https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol54/iss2/3

2020] LIFE AFTER SENTENCE OF DEATH 287

Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Rauf v. State,

78

and the legislature

has not acted to replace the invalidated statute.

6. District of Columbia

Legislative repeal Feb. 26, 1981

No executions after repeal

No executions have occurred in the District of Columbia since

1957.

79

The death-penalty law then in effect was rendered

unconstitutional by the Supreme Court’s dec ision in Furman v. Georgia.

80

On December 17, 1980, the Council of the District of Columbia voted

unanimously to repeal the invalidated death penalty statute, which

lingered on the books. The Death Penalty Repeal Act of 1980 took effect

February 26, 1981.

81

No death sentences have since been imposed or

carried out in Washington D.C.

7. Hawaii

Legislative repeal June 5, 1957

No executions subsequent to repeal

Hawaii became a state in 1959.

82

It has never authorized the death

penalty during statehood.

83

The last execution under civilian authority in

territorial Hawaii was carried out in 1944.

84

The Hawaiian Territorial

https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/local/2018/03/13/delawares-last-death-row-inmates-

resentenced-life-prison-tuesday/407863002/ [https://perma.cc/A6RG-ZEVB].

78. Execution Database (Delaware), supra note 73.

79. DPIC, Executions in the U.S., supra note 36 (showing execution of Robert Carter, April

26, 1957); ICPSR: The Espy File, supra note 29, at Washington, D.C. V16(11), V14 (indicating no

executions after 1957); Execution Database (District of Columbia), DEATH PENALTY INFO. CTR.,

https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/executions/execution-

database?filters%5Bstate%5D=District%20of%20Columbia [https://perma.cc/JUH6-7RZZ]

(indicating no executions 1977 to date).

80. See United States v. Lee, 489 F.2d 1232, 1246–47 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (invalidating sentence

of death imposed under 22 D.C. Code § 2404 in light of Supreme Court’s ruling in Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972)).

81. D.C. Law § 3-113 (1981).

82. Hawaii Statehood, August 21, 1959, NAT’L ARCHIVES, THE CTR. FOR LEGIS. ARCHIVES,

https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/hawaii [https://perma.cc/EG2V-DSEU].

83. See HAW. REV. STAT. § 706-656(1) (2014) (life imprisonment without possibility of parole

is punishment for first-degree murder committed by persons 18 years of age or older).

84. ICPSR: The Espy File, supra note 29, at Hawaii V16 (15), V14; (no executions after 1944);

Jonathan Y. Okamura, Application and Abolition: Race and Capital Punishment in Territorial

Hawai’i, https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/64730/jokamura.pdf

[https://perma.cc/7NEC-4JJB] (identifying the 1944 execution of Adriano Domingo as the last one

21

Acker and Stull: Life After Sentence of Death

Published by IdeaExchange@UAkron, 2021

288 AKRON LAW REVIEW [54:267

legislature passed a bill abolishing the death penalty on June 4, 1957, and

Governor Samuel Wilder King signed the repeal legislation the next day.

85

Two men, Joseph Josiah and Sylvestre Adoca, were under sentence of

death at the time the repeal legislation went into effect.

86

Governor

William F. Quinn commuted Josiah’s sentence to life imprisonment in

1958, after Josiah’s appeal to set aside his 1954 conviction and death

sentence was rejected.

87

The Governor also commuted Adoca’s death

sentence, thus ensuring that no one would be executed under Hawaii law

after the repeal legislation took effect.

88

8. Illinois

Legislative repeal July 1, 2011

No post-repeal executions

The last execution in Illinois occurred when Andrew Kokoraleis died

by lethal injection on March 17, 1999.

89

Governor George Ryan issued

four pardons and commuted the death sentences of the remaining

individuals on Illinois’ death row when he left office in January 2003.

90

A moratorium on executions remained in effect over the next several

years, although offenders continued to be sentenced to death. On March

9, 2011, Illinois Governor Patrick Quinn signed legislation repealing the

carried out in Hawaii); Joseph Theroux, A Short History of Hawaiian Executions, 1826–1947, 25 THE

HAWAIIAN J. OF HIST. 147, 147 (1991). Later executions in Hawaii in 1945 and 1947 were carried

out under military authority. Id. at Appendix II (noting military executions of Cornelius Thomas, on

August 1, 1945, and of Garlon Mickles, on April 22, 1947).