THE POWER

OF EXAMPLE

WHITHER THE BIDEN

DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

Amnesty International is a movement of

10 million people which mobilizes the

humanity in everyone and campaigns for

change so we can all enjoy our human

rights. Our vision is of a world where those

in power keep their promises, respect

international law and are held to account.

We are independent of any government,

political ideology, economic interest or

religion and are funded mainly by our

membership and individual donations.

We believe that acting in solidarity and

compassion with people everywhere can

change our societies for the better.

© Amnesty International 2022

Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a

CreativeCommons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence.

https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode

For more information please visit the permissions page on our website:

www.amnesty.org amnesty.org

First published in 2022

by Amnesty International Ltd

Peter Benenson House, 1, Easton Street

London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom

Index: AMR 51/5484/2022

Original language: English

AMNESTY.ORG

Cover photography by Scott Langley

01

06

07

16

22

27

34

38

41

47

51

57

59

63

68

TABLE OF

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Key Recommendations

1. THE POWER OF EXAMPLE

1.1 Whither the Biden Death Penalty Promise?

2. 'THIS IS NOT JUSTICE'

2.1 Arbitrariness: “The antithesis of the rule of law”

2.2 Rejection of mitigation and rehabilitation

2.3 Race matters

2.4 Mental disability and legal representation

2.5 Intellectual disability and outdated diagnostics

2.6 No mercy: Was clemency always a lost cause?

3. INTERNATIONAL LAW

3.1 International covenant on civil and political rights

3.2 Prohibition of racial discrimination

3.3 Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

70

72

75

79

79

87

92

95

97

4. END FEDERAL ENABLING OF STATE DEATH PENALTY

4.1 End federal backstopping for states

4.2 End litigation backing state executions

4.3 End work with states on execution methods

5. COMMUTE ALL FEDERAL DEATH SENTENCES

5.1 The case of Billie Allen

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 Recommendations

APPENDIX: A CENTURY CENTERING ON FURMAN, 1922-1972-2022

ABBREVIATIONS

American Convention on Human Rights

Anti-Drug Abuse Act

Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act

Federal Bureau of Prisons

Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

Department of Justice

Death Penalty Information Center

Economic and Social Council

Federal Death Penalty Act

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

American Convention on Human Rights

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Military Commissions Act

Organization of American States

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

United Nations

ACHR

ADAA

AEDPA

BOP

CERD

DOJ

DPIC

ECOSOC

FDPA

IACHR

ACHR

ICCPR

ICERD

MCA

OAS

UDHR

UN

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

1

“

IN STRIKING DOWN CAPITAL

PUNISHMENT, THIS COURT DOES NOT

MALIGN OUR SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT.

ON THE CONTRARY, IT PAYS HOMAGE TO

IT… IN RECOGNIZING THE HUMANITY OF

OUR FELLOW HUMAN BEINGS, WE PAY

OURSELVES THE HIGHEST TRIBUTE”

Furman v. Georgia, United States Supreme Court, 29 June 1972, Justice Thurgood Marshall concurring

On 29 June 1972, the US Supreme Court issued a landmark

decision, Furman v. Georgia, overturning the country’s death

penalty laws. As states rushed to revise their capital statutes, here

was a golden opportunity for the elected branches of the federal

government to provide principled human right leadership, and

to work for a permanent end to judicial killing across the United

States of America (USA). Such leadership never came. Presidents

from Richard Nixon to Donald Trump offered an unbroken 50-year

thread of support for the death penalty even as they proclaimed the

USA to be a, if not the, champion of human rights in the world.

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY

2

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

Half a century and more than 1,500 executions later, the USA has

a President who campaigned for ofce on an abolitionist platform.

President Joe Biden promised that if elected he would work for

abolition of the federal death penalty and encourage the same at

the state level. However, except for a temporary moratorium on

federal executions, in the eighteen months since he entered the

White House as President, little progress on his abolitionist pledge

has been visible. What is more, his administration’s defense of the

sentences of all of those currently on federal death row – opposing

relief and moving them closer to execution – is cause for concern.

Time is of the essence, and it is passing.

Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases

without exception regardless of the nature or circumstances of

the crime; questions of guilt, innocence, or other aspects of the

case; or the method used by the state to carry out the execution.

The organization does not seek to minimize the seriousness of

violent crime or to downplay its consequences on individuals,

their families, and the wider community. The death penalty is a

punishment, however, that is a symptom of violence not a solution

to it, and one which expands the grief and suffering of the relatives

and loved ones of murder victims to those of the condemned.

It should have no place in any justice system anywhere. While

international human rights law places an expectation on

governments to ensure abolition of the death penalty within a

reasonable timeframe, pending abolition that same body of law

requires adherence to stringent safeguards in any application of

capital punishment.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

3

Amnesty International submits that the 50th anniversary of Furman

is an opportune moment for the US administration and members

of Congress to be reminded that the world is waiting for the USA

to do what almost 100 countries have achieved during this past

half century – total abolition of the death penalty.

1

Abolition of

the federal death penalty would be consistent with US obligations

under international human rights law. It would bolster the position

of those states in the USA that have already got rid of the death

penalty or are moving towards doing so. It would set a positive

example to individual state governments that continue to use this

cruel, unnecessary, and awed policy, as well as to the diminishing

list of retentionist countries.

The US Government plumbed a new low between July 2020 and

January 2021 when it carried out 13 federal executions after

none for 17 years. Shortly before the rst of these, a US Supreme

Court Justice warned that the cases of those lined up for federal

execution promised to illustrate the sort of inequities that beset

the death penalty at state level, and which called into question

the constitutionality of the entire system. He was right. Among

the cases of the 12 men and one woman put to death by the

federal government were compelling examples of arbitrariness,

racial discrimination, prosecutorial misconduct, mental disability,

intellectual disability, inadequate legal representation, and the

failure of the authorities to prioritize rehabilitation even in the case

of teenaged offenders (18 and 19 at the time of the crime). The

administration’s drive to get as many individuals as it could to the

death chamber before it left ofce – even in the face of a global

pandemic that hindered defence lawyers representing their death

row clients – generated serious doubts as to whether there was

ever, in any of the cases, a genuine prospect of executive clemency

as international law demands.

1

By the end of 1971, 13 countries had abolished the death penalty in law. Today, that number has risen to 110 – more than half the world’s countries. More than two-thirds

of countries in the world (144) are abolitionist in law or practice.

4

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

This episode was a brutal wake-up call about what can happen

if the fate of individuals on death row is handed to an executive

with an appetite for seeing death sentences through to their

lethal conclusion, and it led to a new interest in US Congress for

abolition of the federal death penalty. However, as the execution

spree fades from the memory, the political will necessary to pass

legislation for abolition is at risk of dissipating too.

This report, then, stems from Amnesty International's concern

that the clock is running on the Biden pledge with little to show

for it. It is not a study of the federal death penalty as such or an

examination of the cases of the more than 40 individuals currently

on federal death row, or of those federal defendants facing death

penalty trials. The report revisits the six-month federal execution

spree in a bid to jog the collective governmental memory of

that shameful episode and to reboot the political commitment

to abolition. It also seeks to remind the US authorities of their

general and specic obligations under international human rights

law in relation to the death penalty, including as provided in the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

For decades, UN treaty monitoring bodies have conducted their

reviews of the USA’s human rights record. Time after time, these

expert bodies have called on the USA to halt executions and work

for abolition. Time after time their calls have been rejected. So

too at regional level. The USA has become something of a rogue

outlier on the death penalty at the Inter-American Commission on

Human Rights, which the USA has routinely ignored when this

expert body has called for stays of execution or commutation of

death sentences. So it was during the federal execution spree too.

Among the issues that have come up in UN and regional human

rights bodies time and time again has been the question of racial

and other discrimination in the application of the death penalty in

the USA. The only conclusion that can be drawn from the refusal of

the US authorities to respond appropriately is that in the end they

care little about the fact that executions cement such injustices

into permanence.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

5

In terms of numbers of death sentences and executions, the

federal death penalty has been a small part of the national picture

since the Furman ruling and the Gregg v. Georgia decision four

years later in which the Supreme Court upheld new state capital

laws. From 1988 (when the federal death penalty was reinstated)

to June 2022, federal cases accounted for 86 death sentences

and 16 executions, compared to more than 5,500 death sentences

and more than 1,400 executions at state level in the same period.

Nevertheless, as far as international law is concerned an execution

in the USA, whether conducted at state or federal level, is a US

execution.

Under international law, the federal government may not point

to the fact that an action incompatible with the country’s

international obligations was carried out by another branch or

level of government to seek to absolve the state party (the USA)

of responsibility for the violation. Moreover, in addition to its own

use of the death penalty, and the profoundly negative human

rights example it has set, the federal government has promoted,

facilitated and defended its use by states. All too often it has been

silent, hiding behind the federal structure to wash its hands of the

death penalty at the state level. It has fended off criticism of the

death penalty on the international stage and led briefs in the US

Supreme Court in support of state authorities defending aspects of

their capital justice system. In some cases, it has even added an

expansionary twist to the reach of the death penalty by seeking it

where the state is unwilling or unable to.

Amnesty International is calling on President Biden to commute

all federal death sentences. They include the death sentence of

Billie Allen, whose case features in the report. Nineteen at the time

of the crime in 1997, he has spent more than half of his life on

federal death row.

Again, the USA’s international law obligations include ending the

death penalty in law within a reasonable timeframe. Half a century

after Furman, and 30 years after the USA ratied the ICCPR, this

timeline has already been far exceeded, still with no nationwide

end to judicial killing in sight. President Biden has held out the

promise to change that. He, his administration, and members of

Congress must redouble their efforts now.

6

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE USA:

• Immediately commute all existing federal death sentences.

• Support a public information campaign about abolition aimed at

demonstrating the facts about arbitrariness, racial bias and impact, errors

and other realities of capital justice; the requirements of international

human rights law; and the national and global trends towards abolition.

TO THE US CONGRESS:

• Immediately work with the White House to promptly enact legislation to

abolish the federal death penalty.

TO THE US DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE:

• Maintain the moratorium on executions until abolition of the federal

death penalty is signed into law and all federal death sentences have

been commuted.

• Support commutation of every current federal sentence of death.

• Work actively to vacate every current federal death sentence rather than

oppose relief.

• Instruct all US attorneys that the government will no longer authorize

pursuit of death sentences in federal prosecutions and ensure motions

are led in all pending federal capital prosecutions to request that the

court allow withdrawal of any active Notices of Intent to Seek the Death

Penalty.

• Actively oppose the death penalty in any litigation in any case in which

the federal government is involved at state or federal level that touches

directly or indirectly on this punishment and make clear in any such legal

materials that the US government is committed to abolition.

TO THE US STATE DEPARTMENT:

• Ensure implementation of outstanding recommendations to the USA

made by UN and regional human rights monitoring bodies, including on

the death penalty.

• Vote in favor of UN General Assembly resolutions on a moratorium on

the use of the death penalty and support other international initiatives in

favor of abolition.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

7

“

LEADERSHIP ON HUMAN RIGHTS GOES

FAR BEYOND MERELY REMINDING OTHER

COUNTRIES OF THEIR OBLIGATIONS

AND COMMITMENTS, POINTING OUT

FAILURES, AND REGISTERING OUR

DISPLEASURE. IT INVOLVES LEADING

BY EXAMPLE, ACKNOWLEDGING OUR

SHORTCOMINGS, AND STRIVING TO

LIVE UP TO OUR HIGHEST IDEALS AND

PRINCIPLES”

US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, March 2021

2

1.0 THE POWER

OF EXAMPLE

8

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

O

n 10 December 1948, the world

adopted the Universal Declaration

of Human Rights (UDHR) as “a

common standard of achievement

for all peoples and all nations”

and pledged to take “progressive measures” to

secure “universal and effective recognition and

observance” of the rights therein, including the

rights to life and to freedom from torture and

other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment

or punishment. On that same day, Carlos

Romero Ochoa was led into California’s gas

chamber and killed with cyanide gas.

3

That

was the last of 13 federal executions in the

USA conducted over a period of six years in the

1940s (see Chart 3 below).

On Human Rights Day, 10 December 2020, US

government carried out the ninth of 13 federal

executions in six months. Eighteen at the time

of the crime, Brandon Bernard had spent half

of his life on death row before being killed by

lethal injection in the federal death chamber in

Indiana. In contrast to a federal administration

xated on execution, a change of mind was

evident among those who had voted for death two

decades earlier. Five of the nine surviving jurors

from Brandon Bernard’s trial now supported

commutation of his death sentence. And the

federal prosecutor who had argued on appeal

for his sentence to be upheld said she no longer

supported his execution. “Like a lot of people”,

she said, “I didn’t think about the day when the

government would take Brandon out of his prison

cell and kill him.”

4

President Joe Biden marked Human Rights

Day 2021 by recalling “the moral leadership

and service of Eleanor Roosevelt as the rst

Chairperson of the Commission on Human

Rights” during drafting of the UDHR and stating

that today the USA “remains steadfast in our

commitment to advancing the human rights of

all people – and to leading not by the example

of our power but by the power of our example.”

5

He could have recalled that Eleanor Roosevelt

had shown exemplary leadership when she had

suggested removing the reference to the death

penalty from a preliminary draft of the UDHR

because of moves afoot in various countries to

abolish it.

6

TODAY, WITH

110 COUNTRIES

ABOLITIONIST IN

LAW, THE WORLD IS

STILL WAITING FOR

AN END TO THE DEATH

PENALTY IN THE USA.

3

Madera Tribune, “Slayer executed after delays”, 10 December 1948.

4

USA Today, “I helped put an 18-year-old Black teen on federal death row. I now think he should live”, 7 December 2020.

5

Proclamation 10321 – Human Rights Day and Human Rights Week, 2021, 9 December 2021.

6

She proposed this change at the second meeting of the Commission on Human Rights on 11 June 1947.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

9

COUNTRY AFTER

COUNTRY AROUND

THE WORLD HAS

TURNED AGAINST THE

DEATH PENALTY

The example set by successive US governments on the death penalty since the 1972 US Supreme

Court ruling in the case of Furman v. Georgia, which overturned the country’s death penalty laws,

utterly failed the test of human rights leadership described by the US Secretary of State in March

2021 (above). Yet in the USA its reintroduction and use at state and federal level have been defended

by president after president, despite mounting evidence of the arbitrariness, discrimination and errors

associated with it. As the line of presidential support for the death penalty continued unbroken after

Furman, presidents from Richard Nixon to Donald Trump promoted the USA as a, if not the, global

human rights champion.

Yet in the USA its reintroduction and use at state

and federal level have been defended by president

after president, despite mounting evidence of the

arbitrariness, discrimination and errors associated

with it. As the line of presidential support for the

death penalty continued unbroken after Furman,

presidents from Richard Nixon to Donald Trump

promoted the USA as a, if not the, global human

rights champion.

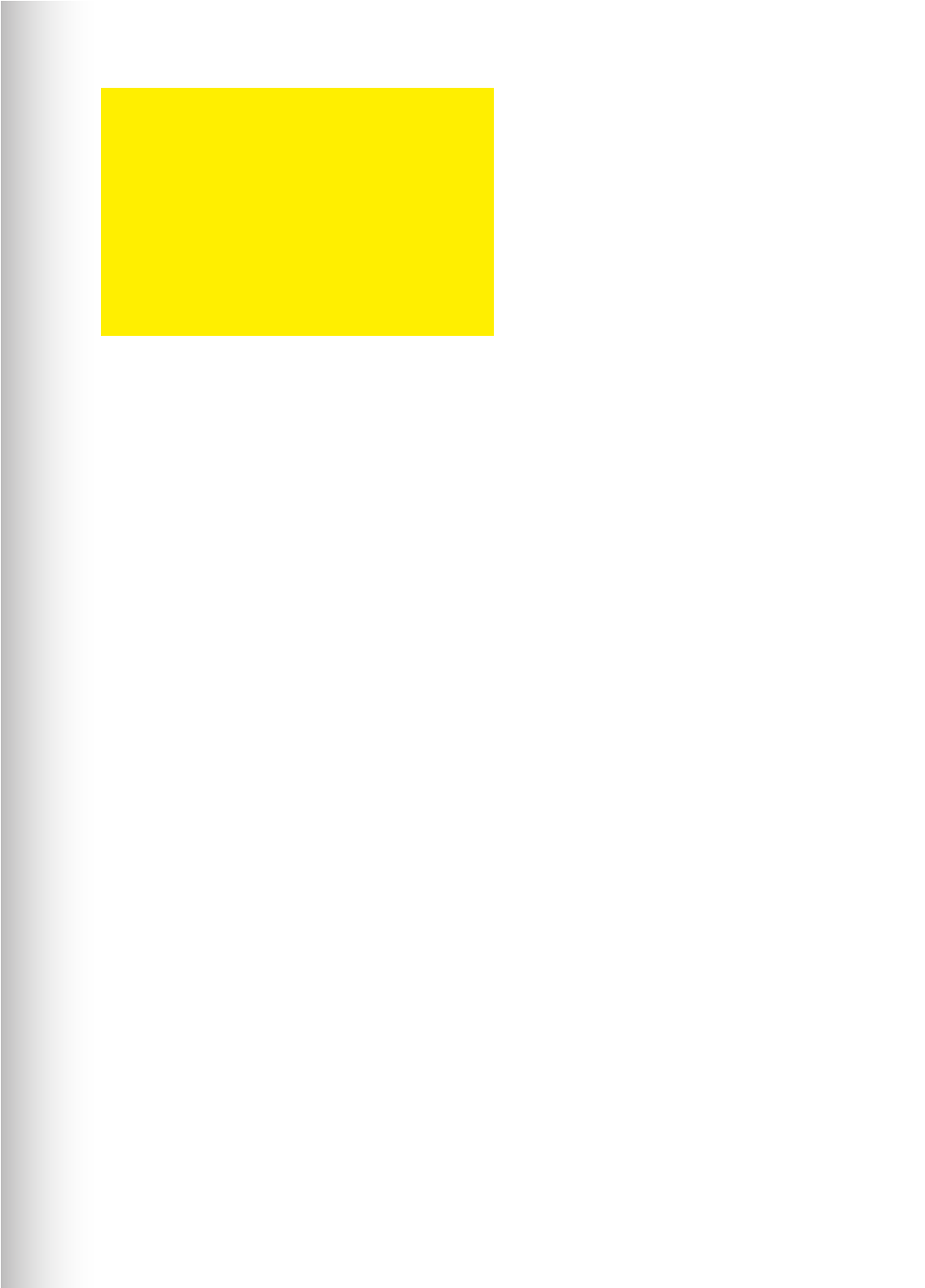

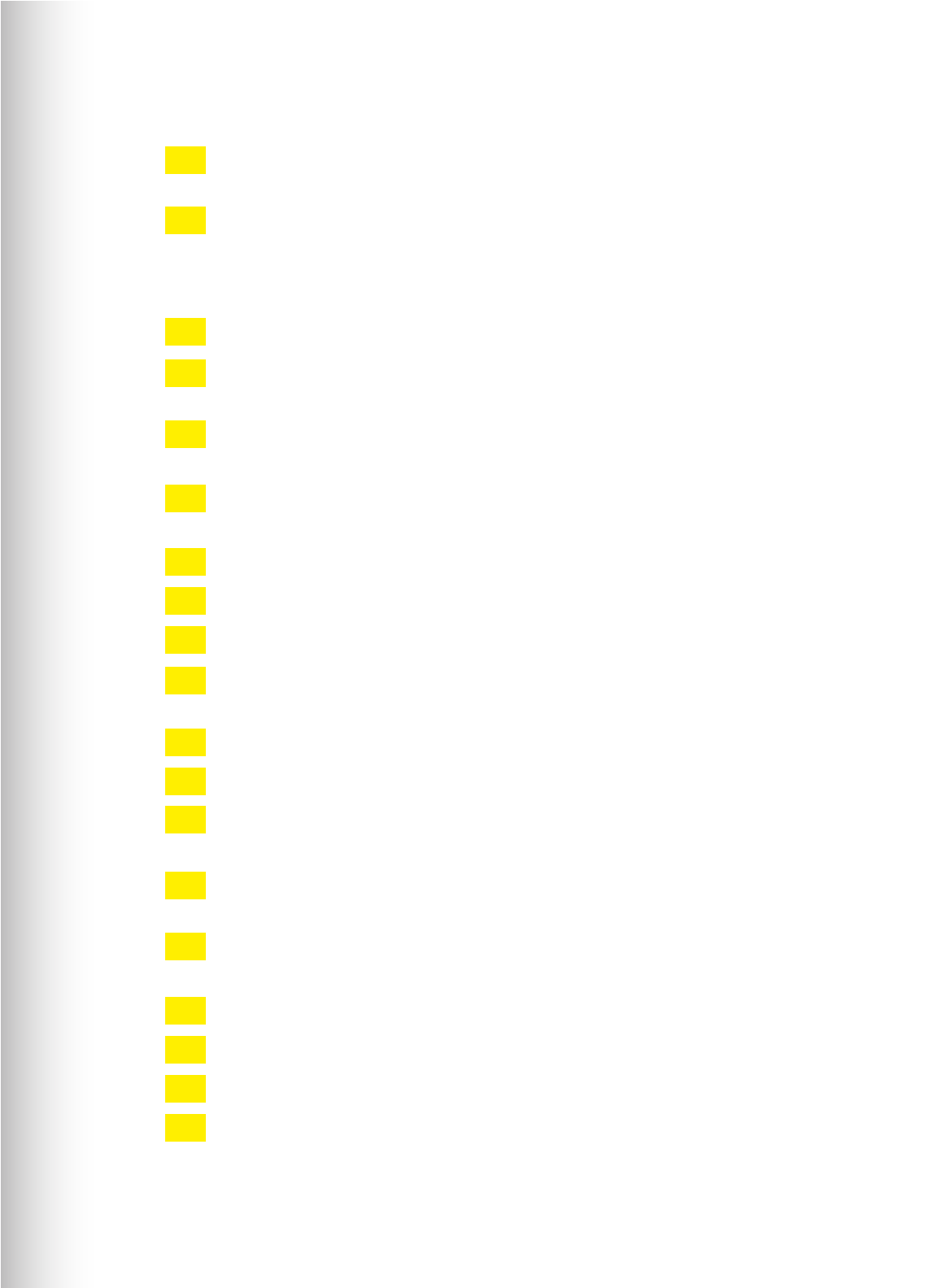

CHART 1: NOTICES OF INTENT TO SEEK THE DEATH PENALTY FILED IN

FEDERAL COURT BY US GOVERNMENT, 1990-2020

(Source: AI chart using data from the Federal Death Penalty Resource Counsel)

50

40

30

20

10

0

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

1

4

9

10

9

20

30

32

34

26

24

28

41

30

26

47

24

18

16

2

3 3

6

5

3

17

7

6

9

15

16

10

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

DEATH AND THE PRESIDENTS SINCE FURMAN

In 1970, President Richard Nixon expressed pride “that our country played an important role

in the founding of the United Nations” and was continuously working “to advance the cause of

human rights.”

7

He nevertheless responded to the US Supreme Court’s Furman v. Georgia ruling

by expressing the hope that it would not apply to federal capital statutes.

8

When it was clear that

it did, he pushed for restoration of the federal death penalty.

9

Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, said the USA had “come to respect and rely on the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights as a fundamental statement of principles reafrming faith in the

dignity and worth of the human person.”

10

Six months later, he expressed strong support for

reintroduction of the federal death penalty for “sabotage, murder, espionage, and treason”,

11

and welcomed the US Supreme Court’s Gregg v. Georgia ruling in July 1976 upholding new state

capital laws.

12

As Georgia’s Governor, Jimmy Carter had signed into law its statute reinstating the death penalty,

approved in the Gregg ruling. Inaugurated as President in 1977, three days after the rst post-

Furman v. Georgia execution, he signed the ICCPR later that year, proposing a broad reservation

to protect the death penalty.

13

President Ronald Reagan asserted that “we’re proud to be champions of freedom and human

rights the world over” and that “the American people cannot close their eyes to abuses of human

rights and injustice… even on our own shores.”

14

He nevertheless made reinstatement of the

federal death penalty an administration goal, greatly politicizing it by equating opposition to the

death penalty with being soft on crime.

15

He lauded the death penalty’s reintroduction in states

“more than 40 of which have acted to adopt appropriate death penalty procedures since the

Furman v. Georgia decision.”

16

The federal death penalty was reinstated under the 1988 Anti-

Drug Abuse Act (ADAA).

President George H. W. Bush ratied the ICCPR on 5 June 1992, saying this underscored the

USA’s commitment to human rights “at home and abroad.” However, US ratication included a

“reservation” to protect the death penalty from international legal constraint, including the ban on

the execution of those under 18 at the time of the crime. After taking ofce, President Bush called

on mayors to “urge your State legislatures to approve the [death] penalty for the killing of local

law enforcement ofcers.”

17

His Attorney General made recommendations to state criminal justice

systems, including giving juries the option of the death penalty for the killing of a law enforcement

ofcer, those who killed during other serious crimes and those who killed in prison.

18

Among the

advisers for this effort was the US Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, Jeff Sessions. He

and the then US Attorney General, William Barr, would become Attorneys General in the Trump

administration three decades later and work to resume federal executions.

7

Proclamation 3996 – United Nations Day, 1970, 10 July 1970.

8

Radio Address about the State of the Union message on law enforcement and drug abuse prevention, 10 March 1973.

9

See, for example, Radio Address about the State of the Union message on law enforcement and drug abuse prevention, 10 March 1973.

10

Proclamation 4408 – Bill of Rights Day, Human Rights Day and Week, 1975, 5 November 1975.

11

Remarks in Anaheim at the Annual Convention of the California Peace Ofcers Association, 24 May 1976.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

11

President Bush lost the 1992 election to Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton, who had made his support for

the death penalty clear. In January 1992, candidate Clinton had own back from the campaign trail

in New Hampshire to be in Arkansas for the execution of Ricky Rector, a man with a severe mental

disability.

19

As President, in his rst term he signed into law the Federal Death Penalty Act (FDPA)

which made nearly 60 federal crimes punishable by death, an expansionist list that one Senator

described as showing “our mad rush to appear tough on crime.”

20

President Clinton also backed

hastening execution: “In death penalty cases, it normally takes eight years to exhaust the appeals;

it’s ridiculous.”

21

Signing the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) into law in April

1996, he said: “criminals sentenced to death for their vicious crimes will no longer be able to use

endless appeals to delay their sentences.”

22

Later that same year, he proclaimed “America’s global

leadership on behalf of human rights”

23

and portrayed his administration as a champion of human

rights. The UN Human Rights Committee condemned the expansion of the federal death penalty,

24

while the UN expert on the death penalty said that the AEDPA undermined fair trial standards

guaranteed under international law.

25

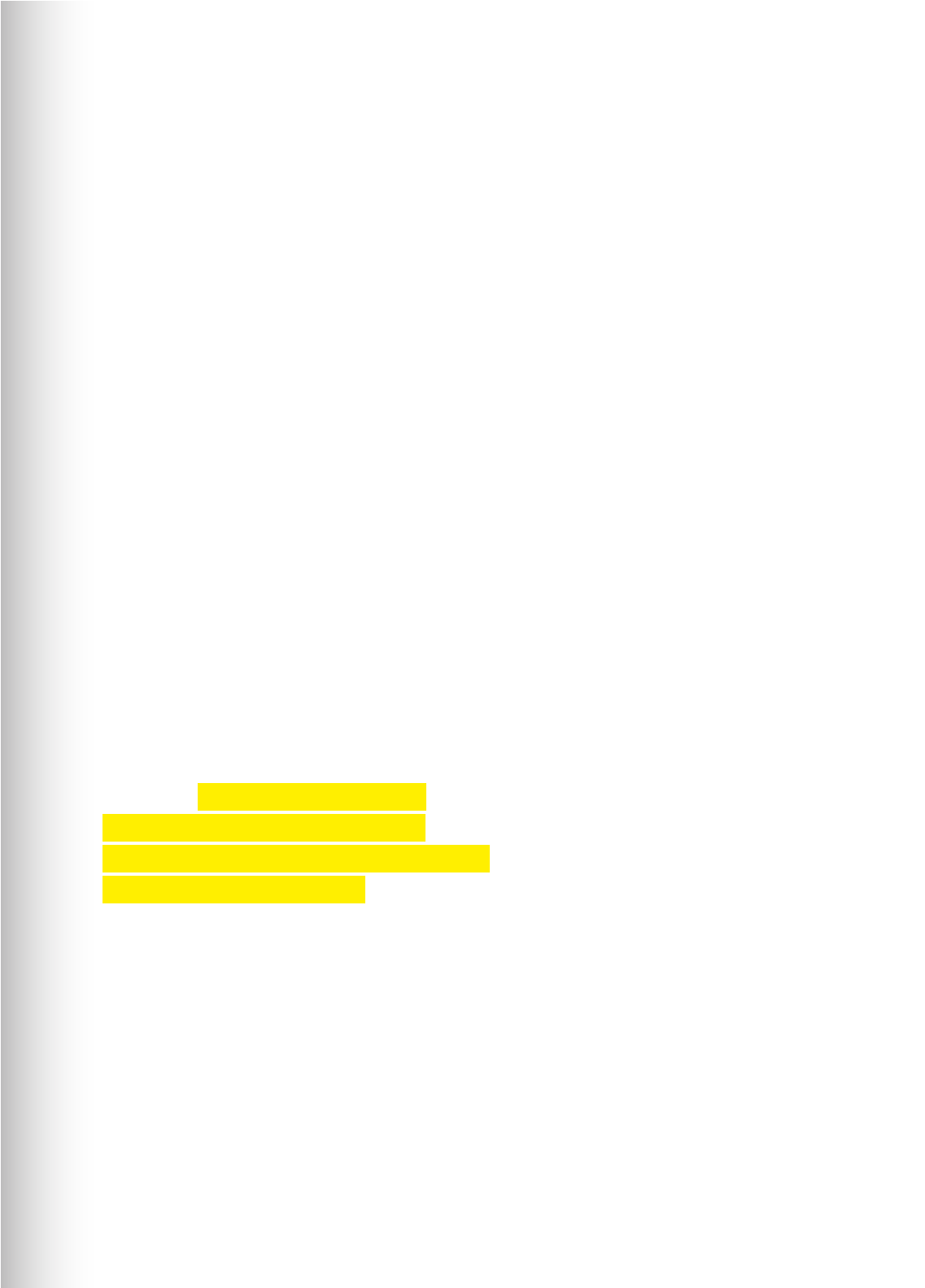

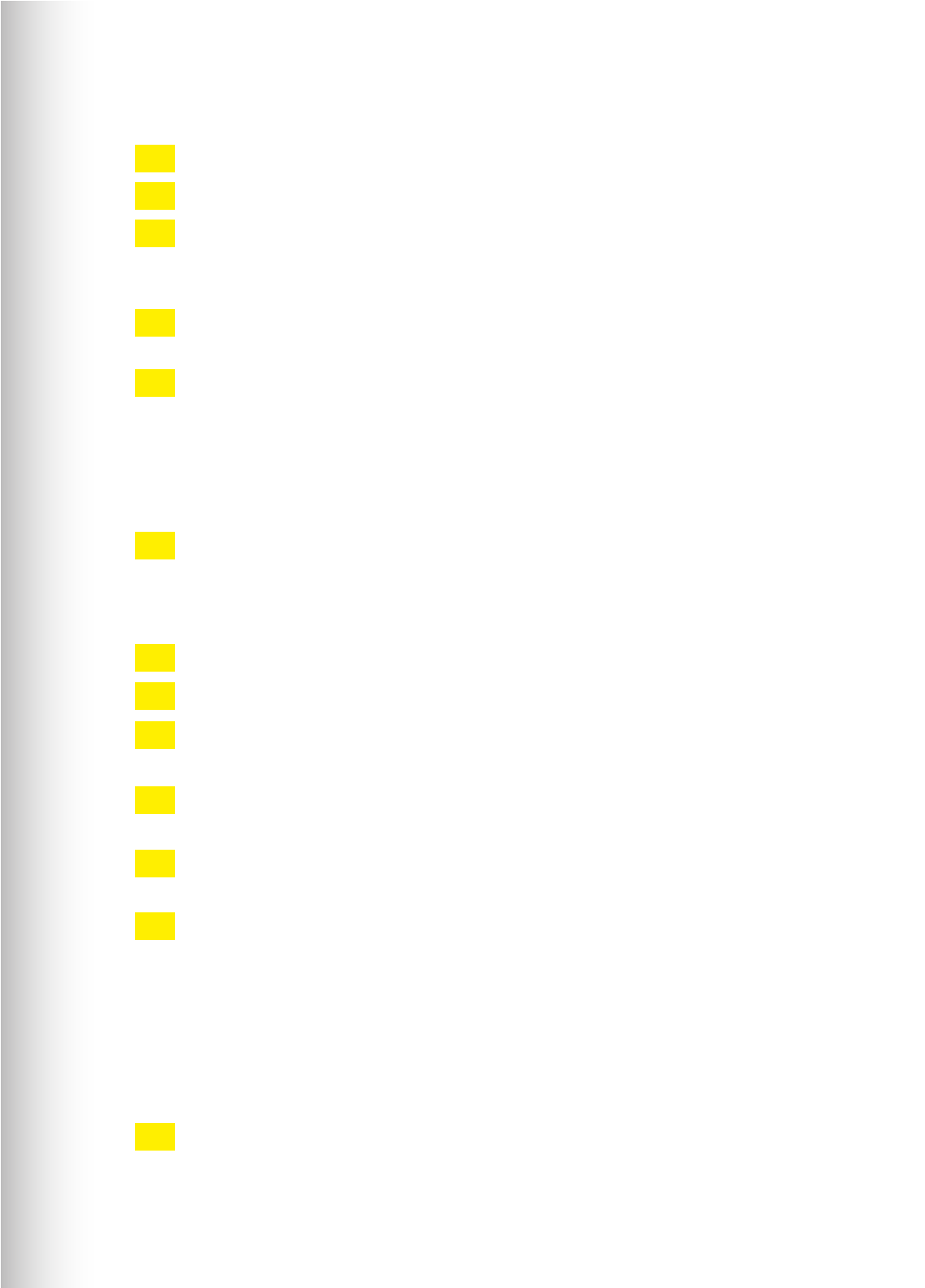

CHART 2: FEDERAL DEATH ROW, 1991-2022

(Source: AI chart using data from the Federal Capital Habeas Project)

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

NUMBER OF PRISONERS IN

FEDERAL DEATH ROW

1 1

6 6

8

11

20

19

22

21

24

27

35

42

45

53

55

57

60

59

59

60 60 60

62

55

45

42

57

56

16

12

The President’s news conference, 9 July 1976.

13

“The United States reserves the right to impose capital punishment on any person duly convicted under existing or future laws permitting the imposition of capital punishment.” In the end,

ratication did not come until 1992, with a similarly broad reservation. Jimmy Carter has since expressed regret at his role in helping to reinstate the death penalty and called for abolition.

14

Remarks on Signing the Bill of Rights Day and the Human Rights Day and Week Proclamation, 10 December 1985.

15

For example, “[T]he liberals, like their agship, the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union], often seem to concern themselves with the rights of criminals and forget about the rights of the citizens

those criminals prey upon. But now they want to get elected, and so they claim they’re tough on crime. Well, I’ve examined that record, and we’ve all got to go out and tell the American people: When

they say they’re tough on crime, don’t you believe it.” Remarks at a Republican Party Fundraiser in Chicago, Illinois, 30 September 1988.

16

1988 Legislative and Administrative Message: A Union of Individuals, 25 January 1988. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, Ronald Reagan, Book 1 (January 1 – July 1, 1988),

page 96-97.

17

Remarks to the United States Conference of Mayors, 26 January 1990.

18

Memorandum to the President, from William P. Barr, Attorney General, Re: Recommendations for State Criminal Justice Systems, 28 July 1992, accompanying: Combating Violent Crime: 24

recommendations to strengthen criminal justice.

12

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

George W. Bush, who entered the White House with his record on executions as Governor of Texas

well known, promised to be a president who would speak for “greater justice and compassion.”

26

However, his support for the death penalty remained undimmed. Within the rst six months of

his presidency, the USA had conducted its rst federal execution in 38 years and another two

within a year of that. In his second inaugural address, he promised that “America’s belief in

human dignity will guide our policies.”

27

Yet federal death row continued to grow, more than

doubling during his time in ofce, and his administration set three executions for 8, 10 and

12 May 2006 (later stayed when the prisoners led a legal challenge to the federal execution

procedures). After the attacks of 11 September 2001, the Bush administration quickly put the

death penalty on the table in a November 2001 presidential order authorizing trials by military

commission, and later obtained congressional approval for the Military Commissions Act (MCA)

of 2006 under which it pursued the death penalty in unfair military commission proceedings at

Guantánamo.

President Barack Obama declared that US leadership in the world was “essential” for promoting

the “dignity and human rights of all peoples” and that the question was “never whether

American should lead, but how we lead.”

28

While his administration was a less ardent proponent

of the death penalty than its immediate predecessors, it took no decisive action against it.

Indeed, it took steps in late 2010 towards scheduling an execution, but in the end no federal

executions took place during the eight Obama years. Hopes that the administration would engage

with states on a national moratorium after a “botched” lethal injection in Oklahoma in 2014

came to nothing after Attorney General Eric Holder left ofce. His successor told senators that

she supported the death penalty as an “effective penalty”.

29

The administration pursued death

sentences in federal court, as well as at Guantánamo under the revised MCA of 2009.

There were 60 people on federal death row when Donald Trump took ofce as president in 2017.

Thirteen federal executions occurred in the nal six months of his presidency. The day after the

last of these executions, President Trump declared the USA to be “a shining example of human

rights for the world.”

30

19

The Atlantic, “The Time Bill Clinton and I Killed a Man” 28 May 2015: “State law did not require the governor’s presence, but politics did: Clinton wanted to raise his national prole and

reverse the Democratic Party’s soft-on-crime image.”

20

Senate Durenberger, Congressional Record – Senate, 17 November 1993.

21

Interview with Larry King, 5 June 1995.

22

Remarks on signing the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, 24 April 1996.

23

Proclamation 6964 - Human Rights Day, Bill of Rights Day, and Human Rights Week, 10 December 1996, and Remarks on Signing the Human Rights Proclamation, 10 December 1996.

24

Report of the Human Rights Committee, United States of America, UN Doc. A/50/40, 3 October 1995, para. 281.

25

Report of 1997 mission to the USA of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, UN Doc. E/CN.4/1998/68/Add.3, 22 January 1998, para. 147.

26

President George W. Bush, Inaugural address, West Front of the Capitol, Washington, DC, 20 January 2001.

27

President George W. Bush, Inaugural address, West Front of the Capital, Washington, DC, 20 January 2005.

28

Statement on the 2015 National Security Strategy, 6 February 2015.

29

Loretta E. Lynch, Conrmation hearing before the Committee on the Judiciary, US Senate, 28 and 29 January 2015.

30

Proclamation 10136 – National Sanctity of Human Life Day, 2021, 17 January 2021.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

13

President Donald Trump’s stance on the death penalty demonstrated its susceptibility to

politicization. After coming to ofce in January 2017, he took to voicing his opinion on individual

cases, including in public comments that outed the presumption of innocence.

President Trump spoke admiringly of China’s death penalty in relation to drugs: “China has much

tougher laws than we do in this country on drugs, so they don’t have a big drug problem in China.

They have a thing called the death penalty.”

32

He also continued his sporadic case commentary.

Responding to a mass shooting in a synagogue in Pittsburgh on 27 October 2018, for example,

he said: “I think one thing we should do is, we should stiffen up our laws in terms of the death

penalty. When people do this, they should get the death penalty, and they shouldn’t have to wait

years and years.”

33

On 26 August 2019, the government led notice of its intent to seek the

death penalty against the defendant. As of early June 2022, this notice had not been withdrawn

and the prosecution was continuing as a capital one.

IN 2018, ATTORNEY GENERAL SESSIONS ISSUED A MEMORANDUM TO

FEDERAL PROSECUTORS ENCOURAGING THEM TO PURSUE THE DEATH

PENALTY FOR DRUG-RELATED CAPITAL CRIMES.

– he tweeted on 1 November 2017, the day after a

driver of a truck left eight people dead and another

dozen injured on a cycle path in Manhattan. In

September 2018, the Trump administration led

notice of its intent to seek the death penalty in the

case. By early June 2022, this notice had not been

withdrawn by the Biden administration.

31

Attorney General Sessions issues memo to US Attorneys on the use of capital punishment in drug-related prosecutions, 21 March 2018, justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-sessions-issues-

memo-us-attorneys-use-capital-punishment-drug-related

32

Remarks in a meeting with Vice Premier Liu He of China, 22 February 2019, and remarks on declaring a national emergency concerning the southern border of the United States, 15 February

2019.

33

Remarks on the shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, at Joint Base Andrews, Maryland, 27 October 2018.

"SHOULD

GET DEATH

PENALTY!"

14

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

Following mass shootings in El Paso, Texas,

and Dayton, Ohio, in August 2019, President

Trump tweeted: “Today I am also directing the

Department of Justice to propose legislation

ensuring that those who commit hate crimes and

mass murders face the DEATH PENALTY – and

that this capital punishment be delivered quickly

decisively and without years of needless delay.”

34

The defendant was charged with capital murder

under Texas state law for the El Paso shootings.

35

He is also facing federal charges with the

possibility of the death penalty. In early 2022,

the prosecution led a proposed schedule

with a July-August 2022 timeline for pre-trial

“constitutional motions relating to capital

punishment.” However, it noted that it had “not

yet qualied this matter as a Death Penalty

case and no inference should be made from

this ling as to whether when, or even if, such a

qualication may be made.”

36

No further decision

had been announced by early June 2022.

William Barr succeeded Jeff Sessions as US

Attorney General in the Trump administration in

early 2019. On 25 July 2019, the administration

informed the US District Court for the District

of Columbia (DC) overseeing the lethal injection

protocol litigation that the government had

adopted a revised addendum to the execution

protocol of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP)

that “provides for pentobarbital sodium as the

lethal agent.”

37

The BOP had “secured the

active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) for

pentobarbital from a domestic bulk manufacturer.

Additionally, BOP has secured a compounding

pharmacy…to convert the API into an injectable

solution.”

38

The very same day, the Attorney

General announced execution dates for ve men

on federal death row in what would be the rst

federal executions since March 2003.

39

While

the government was ultimately enjoined from

carrying out these executions for six months,

the simultaneous release of a new protocol and

setting of execution dates curtailed the likelihood

of successful legal challenges to the changed

protocol, under "the exceedingly high bar"

required to obtain a stay of execution, whatever

the issue.

40

34

Twitter, 5 August 2019, 17:10:05.

35

The gunman in the Dayton shootings had been shot and killed by police during the attack.

36

US District Court for the Western District of Texas, USA v. Crusius, Government’s amended proposed scheduling order, 15 February 2022.

37

US District Court for the District of Columbia (DC), Roane v. Barr, Notice of adoption of revised protocol, 25 July 2019.

38

District Court for DC, Declaration of Raul Campos, In the matter of the Federal Bureau of Prisons Execution Protocol Cases, 12 November 2019.

39

US Department of Justice, “Federal Government to Resume Capital Punishment After Nearly Two Decade Lapse”, 25 July 2019, justice.gov/opa/pr/federal-government-resume-capital-

punishment-after-nearly-two-decade-lapse

40

US Supreme Court, Barr v. Lee, on application for stay or vacatur, 14 July 2020.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

15

On 14 July 2020, over the dissents of four

justices, the US Supreme Court gave the green

light to the federal government to resume

executions under its new protocol. It said

that single-dose pentobarbital had “become

a mainstay of state executions” and had been

“used to carry out over 100 executions” at state

level “without incident.”

41

Twelve of the 13 death sentences were handed

down under Presidents Bill Clinton and George

W. Bush, with the 13th under President George

H. W. Bush. These death sentences were imposed

under the ADAA and FDPA, signed into law by

Presidents Reagan and Clinton respectively, and

defended by the administrations of Presidents

Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and

Donald Trump.

41

US Supreme Court, Barr v. Lee, On application for stay or vacatur, 14 July 2020.

THIRTEEN FEDERAL

EXECUTIONS TOOK

PLACE IN THE NEXT

SIX MONTHS.

THE FAILURE OF

HUMAN RIGHTS

LEADERSHIP

HAD COME HOME

TO ROOST.

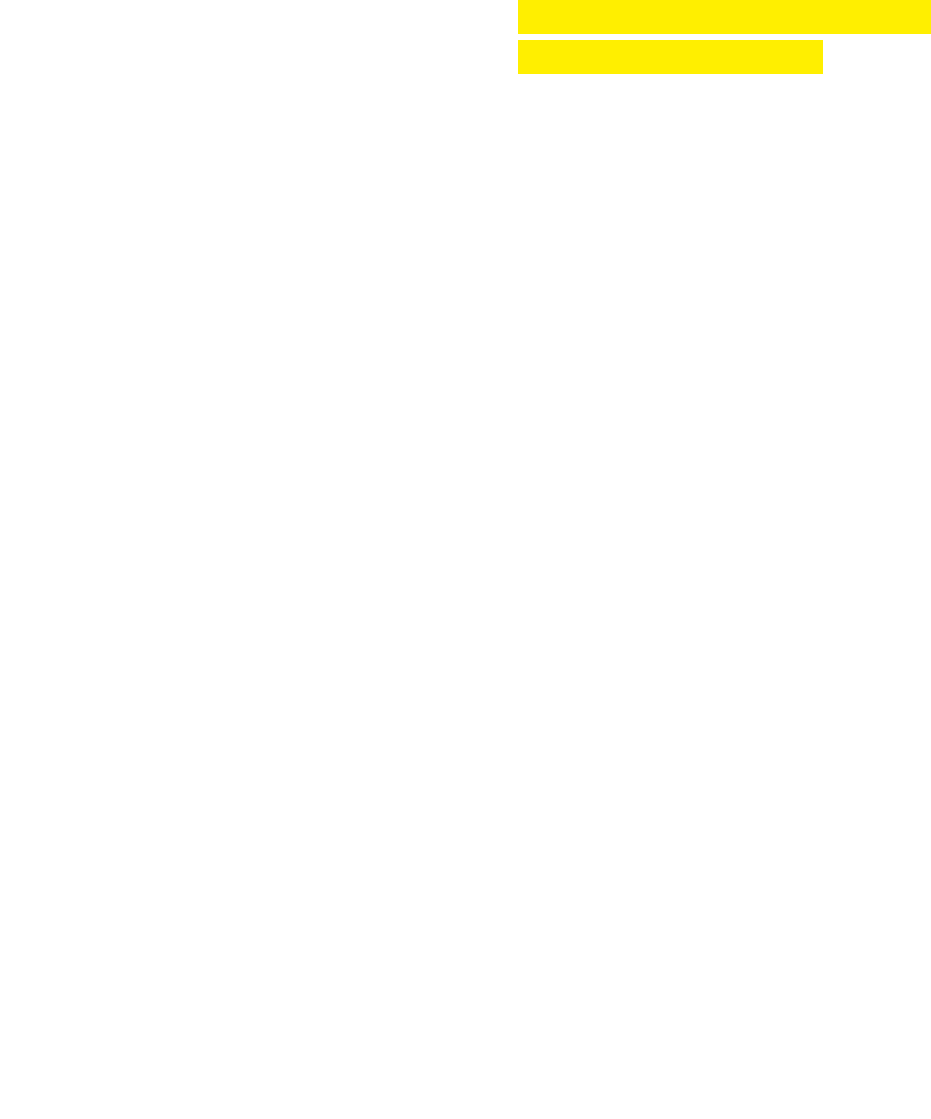

CHART 3: FEDERAL EXECUTIONS SINCE 1920

All post-Furman federal executions have occurred since 2000

(Source: AI chart using data from Federal Bureau of Prisons)

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s 2020s

16

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

1.1 WHITHER THE

BIDEN PROMISE?

IN A BREAK WITH THE PAST, HIS OWN INCLUDED, JOE BIDEN CAMPAIGNED

FOR THE PRESIDENCY IN 2020 ON THE PLEDGE THAT IF ELECTED

HE WOULD “WORK TO PASS LEGISLATION TO ELIMINATE THE DEATH

PENALTY AT THE FEDERAL LEVEL AND INCENTIVIZE STATES TO FOLLOW

THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT’S EXAMPLE.” HIS ADMINISTRATION HAS

CONFIRMED THIS COMMITMENT TO THE UN.

42

In its 1992 report recommending ratication

of the ICCPR, the Senate Committee on

Foreign Relations, with then Senator Joe Biden

among its members, stressed that this human

rights treaty was “part of the international

community’s early efforts to give the full force

of international law to the principles of human

rights embodied in the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights.”

43

As President, he has said that

from the UDHR have “sprung transformational

human rights treaties and a global commitment

to advance equality and dignity for all as the

foundation of freedom, peace, and justice. As

a world, we have yet to achieve this goal, and

we must continue our efforts to bend the arc of

history closer to justice and the shared values

that the UDHR enshrines.”

44

Several states of the USA are well ahead of the

federal government on the abolitionist curve.

They include Virginia, where, on 24 March

2021, Governor Ralph Northam signed a bill to

abolish the death penalty in his state.

45

“This is a

major change”, said the Governor, “because our

Commonwealth has a long history with capital

punishment. Over our 400-year history, Virginia

has executed more than 1,300 people, more than

any other state… Virginia’s history, we have much

to be proud of, but not the history of capital

punishment.”

42

For example, see Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), Combined 10th to 12th reports submitted by the USA under article 9 of the Convention, 8 June 2021, UN Doc. CERD/C/

USA/10-12, para. 116.

43

ICCPR, Report from Senator Clairborne Pell, Chair of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, 24 March 1992.

44

Proclamation 10321, 9 December 2021, (previously cited).

45

Governor Northam Signs Law Repealing Death Penalty in Virginia”, governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/all-releases/2021/march/headline-894006-en.html.

46

Alaska (1957), Colorado (2020), Connecticut (2012), Delaware (2016), Hawaii (1957), Illinois (2011), Iowa (1965), Maine (1887), Maryland (2013), Massachusetts (1984), Michigan (1847), Minnesota

(1911), New Hampshire (2019), New Jersey (2007), New Mexico (2009), New York (2007), North Dakota (1973), Rhode Island (1984), Vermont (1972), Virginia (2021), Washington (2018), West Virginia

(1965) and Wisconsin (1853). Source: Death Penalty Information Center, deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state

47

California (2019), Oregon (2011) and Pennsylvania (2015).

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

17

Today, 23 states are abolitionist.

46

In three other

states, moratoriums on executions remain in

force.

47

But the “continuing long-term erosion of

capital punishment across most of the country”

is being countered by “extreme conduct by

a dwindling number of outlier jurisdictions

to continue to pursue death sentences and

executions.”

48

The 13 federal executions in the

nal six months of the Trump administration

placed the federal government rmly in the

outlier group; the Biden pledge promised to

move it into the abolitionist camp.

As Senator, Joe Biden helped to draft the

1988 ADAA which reinstated the federal death

penalty after Furman v. Georgia.

49

He was

instrumental in the passage of the 1994 Violent

Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act which

incorporated the FDPA, massively expanding the

federal death penalty.

50

He was on the Senate

Foreign Relations Committee when it approved

ratication of the ICCPR with a reservation

aimed at protecting the death penalty from

international legal constraint. He voted for the

AEDPA,

51

although voicing concern about the

risk of executing individuals who had been

wrongfully convicted.

52

It appears that President Biden is still troubled

by wrongful convictions in death penalty cases.

53

He would be in the company of many who have

turned against the death penalty, whether for

moral or pragmatic reasons, after observing its

ineffectiveness, cruelty, errors and inequities.

When signing Virginia’s abolitionist bill into

law in March 2021, for example, Governor

Northam spoke for many when he stated: “as I

have learned more about how the death penalty

is applied in this country, I can say the death

penalty is fundamentally awed.”

The USA's retention of the death penalty

implicates all jurisdictions and branches of

government. The obligations of states parties

to the ICCPR (and those under other treaties)

“are binding on every State Party as a whole.”

Moreover, “[a]ll branches of government

(executive, legislative and judicial), and other

public or governmental authorities, at whatever

level – national, regional or local – are in a

position to engage the responsibility of the

State Party.”

54

48

Death Penalty Information Center, The death penalty in 2021: Year End Report, 16 December 2021, deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/dpic-reports/dpic-year-end-reports/the-death-penalty-in-

2021-year-end-report

49

Senator Joe Biden, AEDPA debate, Senate oor, 7 June 1995: “in 1988, we passed a bill which I had authored with several others called the Death Penalty for Drug Kingpins Act. It was the rst

constitutional Federal death penalty to go on the books after 1972 when the Supreme Court invalidated the death penalty. I helped write that bill, much to the dismay of many of my liberal friends who

could not understand why..”

50

In the Senate on 14 May 1992, he said of the crime bill: “I’ll let you all decide whether or not this is weak… It provides 53 death penalty offences… We do everything but hang people for jaywalking

in this bill.” On 24 August 1994, he responded to accusations from a fellow Senator that the Democrats were soft on crime and had diluted the bill: “My friend says this bill is a product of the Democrats

‘bowing to the liberal wing of the Democratic Party.’ Let me dene the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. The liberal wing of the Democratic Party is now for 60 new death penalties. That is what is in

this bill.”

51

In AEDPA debates, after the Oklahoma City bombing, Senator Biden said: “the constant argument put forward is, we have to do this because once we nd the person who did this awful thing in

Oklahoma and they are convicted and sentenced to death, the death penalty must be carried out swiftly. I might add… the Biden crime bill, is the only reason there is a death penalty.”

IN THE PAST DECADE AND A HALF, 11 STATES IN THE USA HAVE ABOLISHED

THE DEATH PENALTY AND THE ANNUAL NUMBERS OF DEATH SENTENCES

AND EXECUTIONS ACROSS THE COUNTRY HAVE FALLEN.

THE PRESIDENT AND HIS

ADMINISTRATION CANNOT BE THE

ONLY AGENTS OF CHANGE.

18

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

52

Congressional Record, 7 June 1995: “although the death penalty should be applied swiftly and with certainty, the worst thing in the world would be for it to be applied wrongly… Mistakes do happen.

Innocent people are convicted and sentenced to die.”

53

“Since 1973, over 160 individuals in this country have been sentenced to death and were later exonerated. Because we can’t ensure that we get these cases right every time, we must eliminate the

death penalty.” twitter.com/JoeBiden/status/1154500277124251648.

54

UN Human Rights Committee, General Comment 31, The Nature of the General Legal Obligation Imposed on States Parties to the Covenant, 26 May 2004, UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.13, para 4.

55

US v. Higgs, 15 January 2021, Justice Sotomayor dissenting.

56

Barr v. Lee, 14 July 2021.

57

Dunn v. Reeves, Justices Sotomayor and Kagan dissenting (citing US v. Higgs among others): “In essence, the Court turns ‘deference’ [to state court decisions] into a rule that federal habeas relief is

never available to those facing execution.” That the federal government itself allowed the execution of two men who had strong intellectual disability claims to go forward during the federal execution

spree was presumably also not lost on the states. See Amnesty International Urgent Action, 13 January 2022, www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr51/5147/2022/en/

In relation to the role played by the judicial

branch, the decisions of the US Supreme Court

regarding the federal executions generated

widespread concern, including among some of

its Justices. At the end of the spree, Justice

Sonia Sotomayor accused the Court of time

and again having dismissed “credible claims

for relief” without providing the opportunity

for “proper brieng” and usually without “any

public explanation.”

55

The example set by the administration and the

US Supreme Court’s hostility towards “last-

minute intervention” by federal courts, including

but not limited to challenges to execution

protocols,

56

would have been noted by the

diminishing number of states which are the

main drivers of the USA’s attachment to judicial

killing. They include Alabama, where Matthew

Reeves was executed on 27 January 2022. In

2020, the US Court of Appeals for the 11th

Circuit had ruled that his trial lawyers’ failure to

present evidence of his intellectual disability had

been “decient” and that the absence of this

“powerful” mitigating evidence was “sufcient to

undermine condence in the outcome.” In 2021,

the US Supreme Court overturned this without

providing Reeves an opportunity to submit legal

briefs on the matter or provide oral argument.

Three justices dissented; two of them noted

that the decision “continues a troubling trend in

which this Court strains to reverse summarily any

grants of relief to those facing execution”, citing

what had happened during the federal execution

spree, among other things.

57

On 7 January 2022, a US District Court judge

issued an injunction blocking Matthew Reeves’

execution by any method other than nitrogen

hypoxia. Alabama had granted those on death row

a one-off opportunity to choose this new method,

instead of the default method, lethal injection.

Matthew Reeves did not ll in the election

form; his lawyers said he would have chosen

hypoxia. The federal judge agreed that because

of his cognitive decits, Matthew Reeves was

unable to read and understand the form without

assistance and the failure of ofcials to provide

such assistance constituted discrimination on

grounds of disability. The judge ruled it would

not harm the state to delay the execution until

it had developed its nitrogen hypoxia protocol,

which at that stage was said to be a matter of

months away. On 26 January, a three-judge

panel of the 11th Circuit upheld the injunction,

noting among other things, expert evidence

that Matthew Reeves’s “language competency

was that of someone between the ages of 4 and

10”, well below what was required to be able

to understand the execution form. At the 11th

hour, however, the Supreme Court voted 5-4 to

vacate the injunction. Dissenting, three justices

noted that four judges on two courts – “after

extensive record development, brieng, and

argument” – had decided that the execution

should be blocked. Yet, the Supreme Court had

“disregard[ed] the well-supported ndings” made

by the lower courts.

58

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

19

58

Hamm v. Reeves, 27 January 2022, Justice Kagan, joined by Justices Breyer and Sotomayor, dissenting.

59

Ofce of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “UN experts call for President Biden to end death penalty”, ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26876

60

In Alabama, Arizona, Mississippi, Missouri and Oklahoma.

61

In this report, Black and African American are used interchangeably as are Hispanic and Latino, depending on the context, or when quoted,

or used as a datapoint.

62

In his Furman dissent in 1972, Justice Powell wrote: “Many may regret, as I do, the failure of some legislative bodies to address the capital punishment issue with greater frankness or effectiveness...

But impatience with the slowness, or even the unresponsiveness, of legislatures is no justication for judicial intrusion upon their historic powers.” In his concurrence in Baze v. Rees, 16 April 2008,

Justice Stevens said that retention of the death penalty was the product of “habit and inattention” on the part of legislatures, not of the necessary deliberation and evaluation.

63

In 1994 the Clinton administration told the UN that “the majority of citizens through their freely elected ofcials have chosen to retain the death penalty for the most serious crimes, a policy which

appears to represent the majority sentiment of the country”, (Initial report of the USA to the UN Human Rights Committee, UN Doc. CCPR/C/81/Add.4, para. 139). In 2013, the Obama administration

rejected the call of CERD for a moratorium on executions: “the use of the death penalty is a decision left to democratically elected governments at the federal and state levels”, (CERD, Periodic Report of

the USA, June 2013, para. 70).

The White House continues to take a hands-

off stance to imminent executions at the state

level (see Chapter 4). President Biden should

recall the plea from multiple UN experts to full

not just his commitment on the federal death

penalty, but his promise to lead states in the

same direction:

Another year has passed since this call.

Matthew Reeves is one of more than a dozen

individuals who have been put to death at

state level since President Biden took ofce.

60

Familiar racial patterns persist. Of the 15 men

executed between 20 January 2021 and 9

June 2022, 13 were for crimes involving white

victims. Eight of those executed were white, six

were Black and one was Native American.

61

The fact that the judiciary may have upheld

capital laws or declines to block an execution

does not absolve the elected branches of their

human rights responsibilities, not least in the

presence of a judicial philosophy of deference to

those branches.

Despite the failure of Congress and many

state legislatures to address the aws and

human rights violations associated with the

death penalty, on the international stage in an

increasingly abolitionist world, US authorities

have sought to justify resorting to the death

penalty under the rubric of democracy.

63

“THERE IS NO TIME TO LOSE

WITH THOUSANDS OF INDIVIDUALS

ON STATE DEATH ROWS ACROSS

THE COUNTRY AND SEVERAL

EXECUTIONS SCHEDULED AT

STATE LEVEL IN 2021.”

59

IT IS TIME FOR THE

LEGISLATURE AND

EXECUTIVE TO MEET

THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS

OBLIGATIONS. FOR

TOO LONG, THEY HAVE

FAILED TO OFFER

THE NECESSARY

LEADERSHIP.

62

20

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

Six of the 13 executions under President Trump

took place between the 2020 presidential

election and President Biden taking ofce,

with the dates for four of these six set by the

administration after the election. This was

the rst time in 132 years that the federal

government had conducted any executions in

the “lame duck” period. While an execution

conducted at any time is incompatible with

human rights principles,

With three federal executions looming in

the nal week of the Trump presidency,

Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley and Senator

Richard Durbin announced that they would

be reintroducing the Federal Death Penalty

Prohibition Act of 2021, bicameral legislation

to abolish the federal death penalty and require

the re-sentencing of those on federal death row.

The Biden administration has yet to throw its

weight behind such legislation.

The immediate threat of more federal executions

was lifted on 1 July 2021 when the US Attorney

General announced a moratorium pending “a

review of the Justice Department’s policies and

procedures.”

64

By late 2021, the Department of

Justice had withdrawn the government’s notice

of intent to seek the death penalty in some

dozen cases around the country.

65

A new notice

led under the Biden administration in February

2021 was withdrawn in April 2022 and the trial

proceeded as a non-capital case.

66

These are

welcome steps. They are, however, small ones.

Other notices were still in place in June 2022

and the death penalty was being considered in

new cases

67

and in resentencing proceedings.

68

The administration is still defending the death

penalty in individual cases pending trial,

resentencing and on appeal, raising questions

about its resolve on the Biden pledge. And the

review ordered by the Attorney General remains

a narrow one. Despite deep concerns expressed

by both President Biden and Attorney General

Garland about racial disparities and other

chronic problems in the administration of the

death penalty, the authorized review examines

none of them, but revisits only the new,

expediting procedures put in place at the end of

the prior administration.

PRESIDENT TRUMP HAD, AFTER

ALL, LOST THE ELECTION TO AN

OPPONENT RUNNING ON AN

ABOLITIONIST PLATFORM.

64

US Department of Justice, “Attorney General Merrick B. Garland imposes a moratorium on federal executions”, 1 July 2021, justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-merrick-b-garland-imposes-

moratorium-federal-executions-orders-review

65

Houston Chronicle, “Merrick Garland withdrew the death penalty in 12 cases. Does this signal a trend?”, 27 December 2021, houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/AG-Merrick-

Garland-death-penalty-backtrack-16732101.php

66

US District Court for the Western District of Kentucky, USA v. Silvers, Notice of Intent to Seek the Death Penalty, 25 February 2021, and Judicial order on withdrawal of notice, 29 April 2022.

67

For example, US District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, USA v. Meehan, Minute Order, (At indictment, federal defendant advised of “the possibility the Government may seek a death

sentence”) 24 January 2022.

68

Penalty phase retrials were pending in two federal capital cases, involving two men tried in Oklahoma in 2005 (USA v. Rodriguez) and North Dakota on 2006 (USA v. Barrett), but whose death

sentences were overturned on appeal in 2021 due to inadequate legal representation.

THESE SIX

EXECUTIONS IN 59

DAYS ILLUSTRATED

THE HOLLOWNESS OF

THE JUSTIFICATION

THAT EXECUTIONS

IN THE USA REFLECT

THE “WILL OF THE

PEOPLE”.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

21

In one of the cases raising questions about

the Biden pledge, that of the man convicted

of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, the

thread of president-to-president support

remains unbroken. The Obama administration

decided to pursue the death penalty in the

case, obtaining it in 2015. This sentence was

then defended under the Trump administration.

In July 2020, the US Court of Appeals for

the First Circuit vacated the death sentence,

nding that the trial judge had failed to meet

the standard for assessing whether potential

jurors could set aside prejudicial pretrial

publicity about the case.

President Trump tweeted: “Rarely has anybody

deserved the death penalty more... The Federal

Government must again seek the Death Penalty

in a do-over of that chapter of the original trial.

Our Country cannot let the appellate decision

stand. Also, it is ridiculous that this process is

taking so long!”

70

His administration petitioned the Supreme

Court to take the case and “put this landmark

case back on track toward its just conclusion”.

71

The administration led its brief "well in

advance of the due date" and, after the

President lost the election, opposed defence

requests for additional time, arguing that "the

Nation" had a "strong interest in this Court's

hearing and deciding this case this Term".

72

The administration waived the 14-day waiting

period for distribution of its petition.

73

The Court

agreed to take the case soon after President

Biden took ofce. That administration then

led a brief urging reinstatement of the death

sentence.

74

In March 2022, the Supreme Court

did just that, over the dissent of three justices.

75

Uncertainty about where the Biden abolitionist

pledge is going was voiced during oral argument

on this case in October 2021 when US Supreme

Court Justice Amy Barrett pointed out to the US

Deputy Solicitor General that “the government

has declared a moratorium on executions, but

you’re here defending his death sentences.”

IT STRESSED, “JUST TO BE

CRYSTAL CLEAR”, THE “MANY

LIFE SENTENCES” STILL IN PLACE

MEANT THAT THE DEFENDANT

“WILL REMAIN CONFINED TO

PRISON FOR THE REST OF HIS

LIFE, WITH THE ONLY QUESTION

REMAINING BEING WHETHER THE

GOVERNMENT WILL END HIS LIFE

BY EXECUTING HIM.”

69

69

US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, USA v. Tsarnaev, 31 July 2020.

70

Twitter, 2 August 2020, 19:48:20 and 19:48:23.

71

US Supreme Court, USA v. Tsarnaev, Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 6 October 2020.

72

Re: US v. Tsarnaev, Letter to Clerk of US Supreme Court, from Jeffrey B. Wall, Acting Solicitor General, 23 November 2020.

73

Re: US v. Tsarnaev, Letter to Clerk of US Supreme Court, from Jeffrey B. Wall, Acting Solicitor General, 18 December 2020.

74

US Supreme Court, USA v. Tsarnaev, Brief for the United States, June 2021.

75

US Supreme Court, United States v. Tsarnaev, 4 March 2022. Justices Breyer, Kagan and Sotomayor dissented.

76

US v. Tsarnaev, oral argument, 13 October 2021. The Deputy Solicitor General said: “the administration continues to believe the jury imposed a sound verdict and that the Court of Appeals was wrong

to upset that verdict. If the verdict were to be reinstated eventually, which will require some further proceedings on remand, there would then be a round of collateral review, some time for reviewing any

clemency petitions. Within that time, the Attorney General presumably can review the matters that are currently under review, such as the current execution protocol.”

JUSTICE BARRETT SAID THAT SHE

WAS “WONDERING WHAT THE

GOVERNMENT’S END GAME IS

HERE.”

76

SO ARE MANY OTHERS.

22

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

77

US v. Higgs, 15 January 2021, Justice Sotomayor dissenting (“This is not justice”).

2.0 'THIS IS

NOT JUSTICE'

“

AFTER WAITING ALMOST TWO

DECADES TO RESUME FEDERAL

EXECUTIONS, THE GOVERNMENT SHOULD

HAVE PROCEEDED WITH SOME MEASURE

OF RESTRAINT TO ENSURE IT DID SO

LAWFULLY. WHEN IT DID NOT, THIS

COURT SHOULD HAVE. IT HAS NOT”

US Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, 15 January 2021

77

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

23

78

For example, remarks made at a “Great American comeback” rally in Jacksonville, Florida, 24 September 2020: “[This election is] about law and order... they said, ‘Oh, don’t say “law and order.

That’s too tough a term’… I said, ‘No, no, it’s about law and order.’”

79

Throughout the case prior to this, the government acknowledged that Lee's co-defendant was the more culpable actor, both in terms of the crime in question and his previous history. The

government misconduct stemmed from an argument made at the sentencing that Lee was responsible for a prior murder which documents after the fact disproved (see Section 2.1).

80

Campaign press release, “President Trump ensured total justice for the victims of an evil killer”, 15 July 2020.

81

US Supreme Court, Gregg v. Georgia, 2 July 1976, Justice Brennan dissenting.

82

Deposition of Brad Weinsheimer, In the matter of the Federal Bureau of Prisons Execution Protocol Cases, 29 January 2020.

83

Deposition of Brad Weinsheimer, 29 January 2020, (previously cited).

84

US Department of Justice, “Executions Scheduled for Four Federal Inmates Convicted of Murdering Children”, 15 June 2020, justice.gov/opa/pr/executions-scheduled-four-federal-inmates-

convicted-murdering-children

SUCH LANGUAGE SERVES AS A REMINDER OF

HOW THE DEATH PENALTY “TREATS MEMBERS

OF THE HUMAN RACE AS NONHUMANS,

AS OBJECTS TO BE TOYED WITH AND

DISCARDED.”

81

T

he backdrop to the resumption of

federal executions was public concern

and debate about the role of race

in law enforcement and criminal

justice, as well as the looming 2020

presidential election, with the incumbent running

on “law and order”.

78

The White House failed

to resist the temptation to politicize the federal

executions and ignored the ever-present concerns

about racial discrimination in the application of

the death penalty.

The day after the rst of the 13 executions,

that of Daniel Lee (see Section 2.1), President

Trump sought to portray candidate Biden’s

position against the death penalty as political

expediency, of his merely having “joined the rest

of the radical Democrats running for president in

opposing it.” President Trump himself exploited

Daniel Lee’s execution for electoral gain, while

making no reference to the arbitrariness or

government misconduct which marked out the

death sentence implemented in the Lee case.

79

“Joe Biden would have let this animal live”,

went the President’s campaign press release,

referring to the “evil monster” executed a few

hours earlier.

80

The Trump administration chose which of those

on federal death row it would execute and in

which order. The nal decision was taken by

Attorney General Barr, from a list drawn up in

“late spring or early summer of 2019” by the

BOP, with assistance from the Criminal Division

of the Department of Justice, of 14 individuals

who had “exhausted their appellate and post-

conviction remedies.”

82

The Department of Justice announcement in

2019 of the rst federal execution dates stressed

that each of the ve men was “convicted of

murdering children”, which it has indicated

was the reason for scheduling those individuals

rst.

83

It reiterated this aspect of the cases a year

later.

84

The same line was repeated by the US

Supreme Court itself, despite its irrelevance to

the question before it – namely, whether to give

the federal government the go-ahead to use its

new one-drug execution method.

85

24

THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: WHITHER THE BIDEN DEATH PENALTY PROMISE?

85

Barr v. Lee, 14 July 2020: “The plaintiffs are all federal prisoners who have been sentenced to death for murdering children.”

86

White House press brieng by Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany, 1 October 2020.

87

For example, in its Concluding observations on the USA, 18 December 2006, UN Doc. CCPR/C/USA/CO/3/Rev.1, para. 29, the UN Human Rights Committee said that the Bush administration did

not seem to “fully acknowledge” the disproportionate imposition of the death penalty on minorities and low-income individuals. And on 10 March 2010, the Obama administration was accused by a

federal judge of a “dismissive attitude” to the “disturbing statistics regarding the disproportionate number of minorities being prosecuted for capital offenses and sentenced to death” (US District

Court, Eastern District of Louisiana, US v. Johnson, Order and Reasons). The administration had responded to lawyers’ motion for discovery to support a claim that the prosecution in a capital case in

Louisiana had been inuenced by race by stating that it was merely “a variant of a claim that has become perfunctory in modern federal capital cases” and should be denied. The judge denied the

motion, but stated that he did “not doubt that conscious or, more insidiously, unconscious racism can inuence decision-making, from an initial arrest by police through a nal decision by a jury”,

noting “with dismay the dismissive attitude of the government with regard to this issue.”

88

Deposition of Brad Weinsheimer, 29 January 2020, (previously cited).

89

Twenty-one white people have been executed in the USA since 1972 for crimes involving solely Black victims. By the end of May 2022, 14 times as many Black people (300) had been executed for

crimes involving solely white victims.

The ve executions announced in the 25

July 2019 news release were stayed. On 15

June 2020, however, the Justice Department

announced execution dates for four men on

federal death row, all of whom were white.

First in line was Daniel Lee. He had long since

abandoned the white supremacist beliefs

alleged by the government’s trial evidence. Yet

as the national debate about systemic racism

continued, in the lead-up to the execution, the

administration emphasized Lee's connection

to white supremacy (without qualication) and

then exploited it afterwards to bolster President

Trump’s anti-racist credentials. Pressed for a

categorical statement that he denounced white

supremacy and the groups that espoused it,

the White House responded: “This President

had advocated for the death penalty for a white

supremacist, the rst federal execution in 17

years.”

86

On the one hand the administration was willing

to exploit Daniel Lee’s involvement in a white

supremacist organization for its own ends, while

on the other it perpetuated the failure of the

federal government to address the long-standing

and compelling statistical and other evidence

of racial discrimination in the application of the

death penalty.

87

In total, six of the 13 federal executions were

of white individuals, ve men and one woman,

convicted of the murder of white victims. One

was of a Native American man convicted of the

murder of two Native American people. The

other six executions were of Black men, four

convicted of murders involving Black victims,

and two involving white victims.

89

RACE WAS NOT A CONSIDERATION

IN SETTING THE EXECUTIONS,

ACCORDING TO THE DEPARTMENT

OF JUSTICE.

88

NEVERTHELESS,

WHETHER BY DESIGN OR

HAPPENSTANCE, FIVE OF THE

FIRST SIX FEDERAL EXECUTIONS

WERE OF WHITE MEN (CONVICTED

OF KILLING WHITE VICTIMS),

ENSURING THAT THE NATIONAL

DEBATE ABOUT RACISM REMAINED

SOMEWHAT PARTITIONED OFF

FROM THE ISSUE OF FEDERAL

EXECUTIONS RESUMING.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

25

90

US District Court for the Western District of Texas, USA v. Bernard, Government’s consolidated response to Bernard’s motion to modify sentence under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1) and motion to stay or modify

execution date, 8 December 2020.

91

US District Court for the Western District of Texas, USA v. Bernard, Reply in support of motion to modify sentence under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1), 8 December 2020.

92

Ofce of Public Affairs, US Department of Justice, “Federal government to resume capital punishment after nearly two decade lapse”, 25 July 2019, justice.gov/opa/pr/federal-government-resume-

capital-punishment-after-nearly-two-decade-lapse.

93

US District Court for DC, Montgomery v. Barr, Defendants’ response in opposition to motion for Temporary Restraining Order and preliminary injunction, 14 November 2020. Barr v. Purkey, Application for

a stay or vacatur of the injunction issued by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, In the US Supreme Court, July 2020: “the last-minute injunction is intensely disruptive to BOP’s

preparations for the execution… including picking up grieving family members of the victims and other witnesses at the airport and preparing to transport them to the execution facility.”

94

For example, US Supreme Court, Mitchell v. USA, Response in opposition to emergency application for stay of execution, August 2020: “any further delay would disserve the interests of the government, the

victims’ families, and the public.”

95

A federal judge accused the administration of “pervasive indifference” towards the interests of family members and granted a motion for a preliminary injunction given the setting of execution dates

during the Covid-19 pandemic, with all the health risks that posed, including for travel; US District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Peterson et al, v. Barr et al. Order granting plaintiffs’ motion for

preliminary injunction, 10 July 2020. The Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit overturned the order after the government appealed.

96

In re Lezmond Charles Mitchell. Memorandum in support of petition for clemency and for commutation of death sentence. Before the President of the United States and the US Pardon Attorney, July 2020.

In the case of the latter two Black federal

defendants jointly convicted of the murder

of two white people committed when the

defendants were 18 and 19 years old, lawyers

for one of them urged a federal judge to

recognize the role of the now discredited

“superpredator” myth on the decision by

the Clinton administration to seek the death

penalty in the case. With one of the two

already executed, and the second scheduled

for execution, the government protested that

the lawyers were “accusing the prosecution

of racism”,

90

to which the defense lawyers

responded:

The Department of Justice’s 2019 news release

announcing resumption had also said that

“we owe it to the victims and their families

to carry forward the sentence.”

92

In litigation

opposing delays to its execution schedule, the

Trump administration repeatedly pointed to

the “overwhelming interest” of victims’ family

members in having the executions carried out.

93

It did so even in cases where victims’ relatives

opposed the execution.

94

In at least two of

the cases – those of Daniel Lee and Lezmond

Mitchell – family members of the murder

victims made vigorous efforts to have the death

sentences reduced to life imprisonment.

95

In

Lezmond Mitchell’s case, they included the

grandson and cousin of the two victims. He

had initially supported the death sentence, but

now believed “that to take another person’s life

because he made a mistake is not forgiving. It

is revenge.”

96

"That defensive response misses the point.

The reality is that everyone in this society is

inuenced by racial bias – that’s the heavy

hand of the past and the present that rests on

everyone’s shoulder, including the writers of this

document… [T]he sad truth of the matter is, that

in the late 90s unconscious racial bias expressed