Hacienda Pública Española / Review of Public Economics, 215-(4/2015): 63-94

© 2015, Instituto de Estudios Fiscales

DOI: 10.7866/HPE-RPE.15.4.3

The Discretionary Fiscal Effort: An Assessment of Fiscal

Policy and its Output Effect

*

NICOLAS CARNOT

FRANCISCO DE CASTRO

European Commission

Received: December, 2014

Accepted: July, 2015

Abstract

This paper presents an indicator of the scal stance that combines features of the bottom-up, narrative

approach on the revenue side with a rened version of the top-down, traditional approach of the struc-

tural balance on the expenditure side. With these characteristics the indicator offers an image of scal

policy that assuages the «endogeneity problems» of the structural balance and avoids the «indeterminacy»

of the narrative approach. This indicator is used to shed light on EU scal policies and estimate the

average short-term output effects of scal policy. Results indicate that, with exceptions, scal policy

has been conducted in a more stop and go and pro-cyclical fashion over the past decade than suggested

by traditional indicators. The scal multiplier is estimated at around 0.75 on average, with higher (resp.

lower) multipliers associated with expenditure (resp. revenue) shocks, and higher (resp. lower) multi-

pliers in times of declining (resp. increasing) output gaps.

Keywords: Fiscal Stance; Discretionary Fiscal Effort; Fiscal Consolidation; Fiscal Multipliers.

JEL Classication: E62, H60.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, it presents an indicator of the scal stance,

the discretionary scal effort (DFE), which is less exposed to the common robustness and

endogeneity problems of standard measures such as the cyclically-adjusted (or structural)

balance. Second, the paper uses this indicator to empirically estimate the short-term output

effect of a change in scal policy (the scal multiplier), and the composition- and state-de-

pendency of that effect, across a panel of EU countries over the past decade.

*

We thank Jan in’t Veld, Philipp Mohl, Lucio Pench, Eric Ruscher, Matteo Salto, Stefan Zeugner, the participants

at the XXII Encuentro de Economía Pública, the XVIII Encuentro de Economía Aplicada, the Workshop on Fiscal

Multipliers at the ESM (Luxembourg) and two anonymous referees for very useful discussions and comments. Any

remaining errors are our exclusive responsibility. The views in the paper are those of the authors and should not

be attributed to the European Commission. Contact: Nicolas Carnot, DG ECFIN, European Commission, CHAR

12/078, B-1049 Brussels, Belgium, [email protected]; Francisco de Castro, DG ECFIN, European Com-

mission, CHAR 12/093, B-1049 Brussels, Belgium, [email protected]

64

The questions of isolating the policy-driven part of scal developments, as opposed to

their endogenous response to the environment, and of evaluating the short-term impact of

scal changes on activity, are long-standing ones in the literature (Blanchard, 1990). Both

questions have given rise to an abundant research, with renewed interest in recent years as

the economic and nancial crisis has revived discussions about the macroeconomic role of

scal policy.

In a traditional approach, the structural balance, or rather the change therein, is taken as

a suitable measure of the scal stance

1

. This is a top-down and outcome-oriented indicator

of scal policy, which benets from being widely-known and routinely calculated. An im-

portant strand of the literature indeed relies on this notion when investigating topics such as

the impact of stimuli packages or the (non-)success of budgetary consolidation episodes (see

e.g. Alesina and Perotti, 1995; Ardagna, 2004; Kumar et al., 2007; and European Commis-

sion, 2010). However, the structural balance has been increasingly criticised as a measure of

the scal effort given in particular the empirically large uctuations in the response of tax

revenues and unemployment spending to the output gap (see, among many, Eschenbach and

Schucknecht, 2002; Lendvai et al., 2011; Hers and Suyker, 2014). This «endogeneity fea-

ture» of the structural balance is especially problematic for estimating the scal multipliers

from observed data (Guajardo et al., 2011).

As a possible alternative, the «narrative approach» evaluates the scal effort by adding

up the measures adopted in actual budgets and reported in budget documentation or other

veriable communication (Romer and Romer, 2010). The narrative approach gives a bottom-

up metric of scal actions which has been argued to be more robust than the traditional ap-

proach when identifying scal innovations and estimating multipliers (Favero and Giavazzi,

2010; IMF, 2010; Ramey, 2011 and Guajardo et al., 2011). However, in the narrative ap-

proach it is not clear whether and why an absence of identied measures can genuinely be

equated with a neutral policy stance. Nor is it straightforward to inventory scal actions in a

manner that is encompassing enough for practical purposes (Devries et al., 2011, make an

attempt for consolidation measures).

The approach taken in this paper uses a combination of the traditional and narrative ap-

proaches. On the revenue side, our indicator relies, like the narrative approach, on a bottom-

up assessment. It does so while making use of the data on new tax measures collected and

increasingly scrutinised as part of EU scal surveillance. On the expenditure side, our

method is close to the traditional top-down approach of the structural balance, although it

makes two adjustments: one is removing from the expenditure aggregate a couple of

spending items deemed beyond the authorities’ control in the short-run (interest and unem-

ployment expenditures); the other is using a smoother notion of potential growth than usual.

Thereby the trend against which expenditure policies are benchmarked is more stable, and

deviations from that trend are better proxies of actual policy changes.

With this set of choices the discretionary scal effort is meant to reduce the endogene-

ity issues disturbing the structural balance, as it is not exposed to short-term gyrations in tax

65

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

or unemployment spending elasticities. At the same time it mitigates the challenges of the

narrative approach as, rst, it relies on a dedicated data set of revenue measures, and second

a null value of the discretionary scal effort can more consistently be equated to a neutral

scal stance. These properties allow using the indicator to shed new light on the conduct

of EU scal policies, in complement to the standard approach of the structural balance.

The empirical part of this paper conrms that the description of scal policies is to an

important extent inuenced by the choice of approach. While over time the discretionary

scal effort and the change in the structural balance tend to convey the same messages, size-

able differences between the two indicators are observed at critical specic episodes. Depar-

tures of actual revenue elasticties from their average value (e.g. windfalls or shortfalls in li-

aison with the boom and bust cycles) are a major contributor to the gap between the change

in the structural balance and the discretionary scal effort, with other factors playing also a

role. In particular, the discretionary scal effort suggests that, with some exceptions, scal

policy in the EU has been conducted in a more stop and go and pro-cyclical fashion over the

past ten years than suggested by traditional indicators.

As the properties of the discretionary scal effort permit interpreting it as a reasonable

proxy for scal shocks, it feeds naturally into an empirical study of scal multipliers. Our

methodology relates output growth to the discretionary scal effort and other controlling

factors in a panel of EU countries. In order to avoid endogeneity issues we rely on GMM

estimates. Signicant limitations of our empirical work, however, relate to the relatively

limited time span, the uncertainty in parts of the data (notably the yields of tax measures in

early years of the panel), and the panel approach which only allows us to estimate an

average, non-country dependent multiplier.

With these caveats in mind we nd point estimates of rst-year output multipliers a bit

below unity on average, of the order of 0.75 (given lags, second-year multipliers are slightly

above unity). Fiscal multipliers are known to depend largely on the composition of scal

shocks and on circumstances. By breaking down the discretionary scal effort between ag-

gregate expenditure and revenue shocks, we nd, in line with the majority of other papers,

higher expenditure multipliers (of the order of 0.9-1.0) than revenue multipliers (around

0.35). We also attempt to differentiate multipliers with economic conditions using as a proxy

thereof different combinations of the output gap. While results based on the level of the

output gap are not entirely conclusive in our panel, we nd some differentiation between

good and bad times as dened by a positive (respectively negative) change in the output gap.

The average and tax multipliers are found to be signicantly higher in the bad times, where-

as differences for expenditure multipliers are found to be non-signicant.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 motivates the introduction of the

discretionary scal effort, presents its evaluation, and shows how it relates to and differ from

the (change in) the structural balance. Section 3 discusses scal developments across the EU

in the past decade in the light brought by the discretionary scal effort. Section 4 uses the

66

discretionary scal effort to evaluate the short-term output effects of scal shocks in a panel

of EU countries. Section 5 concludes.

2. The discretionary scal effort

2

2.1. Background: traditional and narrative approaches to the scal stance

As noted in the introduction, a growing literature suggests a narrative, bottom-up ap-

proach to assessing the scal stance, which consists in adding up the evaluated yield of

measures presented in budget documents. This approach aims at improving on the change in

the structural balance for identifying the effective size and timing of the policy effort. Indeed,

a widely-known limitation of the structural balance is the presence of signicant windfalls

or shortfalls in revenues (or, to a lesser extent, in unemployment benet spending) that are

not accounted for by standard cyclical corrections. For example, persistent but non-perma-

nent variations in asset prices or changes in the composition of growth can generate shifts in

revenues that are incorrectly identied as structural developments. Technically such wind-

falls or shortfalls translate into actual scal elasticities departing from the ones underlying

the computation of cyclically-adjusted and structural balances.

3

Another challenge stems

from the uncertainty of potential output measurement, particularly in real time where errors

typically turn out to be correlated with cyclical developments.

As a possible alternative, the «narrative approach» evaluates the scal effort by adding

up the measures adopted in actual budgets and reported in budget documentation or other

veriable communication. While the narrative approach overcomes the shortcomings of the

traditional approach, it is not without hard challenges itself. First, it has to rely on a suf-

ciently encompassing informational base. This does not go without saying as the information

available in budget documents may represent only a fraction of the measures actually imple-

mented, both because national budgets do not cover the whole general government sector

(which is relevant from a national accounts perspective) and because measures impacting on

the public nances may be taken outside annual (or supplementary) budgets. In addition, the

information taken from real-time budgets may be biased and can be revised in the light of

further information. Second, while on the revenue side an absence of measure can reasonably

be equated with a neutral stance, there is generally no reason for that to be the case on the

expenditure side. For example, letting entitlements grow above the trend rate of output would

usually be described as non-action in a narrative approach while it would more appropri-

ately be seen as stimulus from a macroeconomic point of view. This «indeterminacy» of a

pure bottom-up on the expenditure side suggests that the benchmark of «no-measure» should

rather be akin to having expenditure grow at a rate in line with a concept of trend output.

Besides, one should preferably employ a rather smooth notion of trend growth in a bottom-

up perspective because only subject to this condition can one interpret an absence of sig-

nicant deviation from that trend with an absence of measures.

67

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

In view of the weaknesses of both the top-down and bottom-up approaches, this paper

presents an alternative indicator, the discretionary scal effort (DFE), which combines fea-

tures of both approaches and arguably largely mitigates the concerns raised above. In par-

ticular, the discretionary scal effort has the attraction of being, by construction, somewhat

less conditioned by the endogeneity problems affecting the structural balance on the revenue

side while relying on a more conventional approach on the expenditure side, thus avoiding a

main shortcoming of the narrative approach, specically the lack of a benchmark against

which to gauge policy choices on the expenditure side.

2.2. The discretionary scal effort: denition

The discretionary scal effort is dened as:

R G

N

R

t

(

∆ E

t

− pot . E

t −1

)

DFE = DFE + DFE = −

(1)

t t t

Y

t

Y

t

where N

R

stands for the incremental budgetary impact of all discretionary revenue measures

in year t, Y is nominal GDP, E is general government expenditure adjusted as indicated

t t

below and pot is medium-term potential growth, as dened subsequently.

The discretionary scal effort represents a mixed method for assessing the scal stance

in the following sense:

• On the revenue side, it relies on a truly bottom-up approach, as the effort is compu-

ted by adding-up the effects of new tax measures in the year of interest. This inclu-

des, when relevant, the incremental effect in a given year of tax measures adopted in

earlier years (see also Annex B). The main difference with the structural balance

stems from the uctuations in tax elasticities from their average values, which are

quite large in practice.

• On the expenditure side however, an essentially top-down method is kept by measu-

ring the effort as the gap between the growth of public spending and potential

growth. This is because of the indeterminacy problem of the narrative approach

noted above, but also for a more positive reason. Dened this way, the discretionary

scal effort indicates whether policy is inducing growth above or below trend GDP.

In particular, a neutral stance corresponds to a situation where the authorities do not

aim at changing the medium-run values of the tax and expenditure to GDP ratios;

that is, there is no attempt to stimulate demand above or below potential growth.

It should perhaps be noted that on the expenditure side, what we call a neutral stance need

not equate the absence of active policy measures (a no policy change scenario). That is be-

cause some expenditure items may naturally follow a distinct trend from potential growth. For

example, entitlements typically increase at unsustainably high pace in the absence of policy

changes. This means that policies would de facto be expansionary in the absence of measures.

68

While the approach to the spending side is more conventional and closer to the struc-

tural balance methodology, two important differences must be underlined:

• First, interest payments and all non-discretionary changes in unemployment expen-

diture are removed from the expenditure aggregate as they are deemed to be outside

the control of policymakers in the short run. The adjusted expenditure is thus:

E =G −U

nd

−I

t t t t

where G is general government expenditure and U

nd

and I refer to non-discretio-

t t t

nary unemployment expenditure and interest payments respectively.

• Second, a «smoother» than usual notion of potential growth is used. Specically, we

use a 10-year moving average of potential growth as estimated in the EU methodo-

logy (D’Auria et al., 2010). Specically:

* *

10

pot =

(

Y / Y

)

1

−1

t t+4 t−5

where Y* is real potential GDP in year t.

4

This notion is the «reference rate» already

t

used when evaluating the expenditure benchmark in the EU scal framework. It is

more stable by construction than the standard measure.

These adjustments are important for getting closer to a time-invariant notion of the un-

derlying scal effort. In particular, for a given amount of expenditure measures, the evalu-

ated scal stance will not too signicantly be affected by temporary uctuations in activity

and potential growth. That is because the expenditure items most clearly beyond the control

of the budgetary authorities in the short-run are removed, and because the trend that serves

as reference to assess expenditure growth is relatively smooth.

In addition, the discretionary scal effort is constructed while netting out one off and

other temporary measures on both the revenue and the expenditure sides. That is, the revenue

measures N

R

and the adjusted expenditure E entering equation (1) are cleaned from one offs

t t

and temporary measures. This is analogous to what is done in EU surveillance for calculating

structural balances. While there is no universal denition of one offs and there are borderline

cases, we rely empirically on the data used in EU surveillance.

2.3. Discussion and limitations

The discretionary scal effort can be conceptually understood as a reformulation, in the

form of an indicator of the scal stance, of the expenditure benchmark introduced into EU

surveillance with the six-pack. There are however, a few technical differences between the

two notions.

5

Overall, by being more directly connected with policy decisions, the discretionary scal

effort overcomes the problems associated with cyclically-adjusted balances when taken as a

69

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

faithful reection of policy decisions on an annual basis. At the same time, the discretionary

scal effort is encompassing enough to be quite tightly connected with overall scal out-

comes in the medium-term, or at least, to supply a roughly right measure of the actual direc-

tion and size of scal policy.

The evidence provided in this paper points to signicant benets from using the discre-

tionary scal effort for enriching the analysis of the scal stance. The discretionary scal

effort suffers from some limitations though:

• First, it relies on estimates of the budgetary costs or savings from tax and spending

measures that come with their own measurement uncertainties, particularly when the

underlying data for evaluating measures is lacking or of poor quality. This is partly

mitigated in our framework by relying on the increasingly scrutinised dataset of dis-

cretionary revenue measures used in EU surveillance. Further progress would howe-

ver be needed to improve the quality and cross-country consistency of these data.

• Second, the choice of trend growth on the expenditure side is the outcome of a fairly

ad hoc procedure which, if effective for obtaining a smooth series, remains linked to

an uncertain evaluation of potential output in the rst place. In addition, because the

evaluation of potential growth is affected by current growth, there may remain a

degree of reverse causality in the relationship between contemporary growth and the

discretionary scal effort. Moreover, discretionary measures might be adopted in

response to underlying macroeconomic conditions. In other words, we can see the

discretionary scal effort as largely but not entirely cleaned from the endogeneity

problems affecting the structural balance, when it comes to estimate the scal mul-

tipliers in a regression model. We deal further with this aspect in the panel estima-

tion (see section 4).

2.4. Decomposition of the differ

ence between the change in the structural balance and

the discr

etionary scal effort

Further analysis of the underlying reasons for the gap between the two indicators can be

performed by breaking down the difference into four main components, as well as a small

residual term capturing other factors (Annex A works out the analytical decomposition):

• Revenues windfalls and shortfalls. This reects the difference between the actual

(i.e. observed each period) and the average (i.e. used in the standard calculation of

the structural balance) semi-elasticity of revenues to the output gap.

6

• Windfalls or shortfalls in unemployment expenditure, as compared with standard

elasticities that capture the average cyclicality of unemployment benets in the

structural balance calculations.

70

• The gap between annual potential growth and medium-term expectations of poten-

tial growth, as measured by the «smoother» reference rate of potential growth, times

the share of expenditure in GDP.

• Changes in interest payments.

Identifying quantitatively the contributing factors to the gap between the two indicators

generally provides further insight about underlying economic developments. It thereby al-

lows a more robust assessment of the direction of scal policy. In practice (see section 3), all

four components may contribute signicantly, although the primary source of difference

appears to be revenues windfalls/shortfalls, followed by the potential growth wedge and then

changes in interest payments.

3. Fiscal developments over the past decade in the EU

This section uses the discretionary scal effort, in comparison with the structural bal-

ance, to revisit scal developments across EU countries over the past decade.

The data used in the empirical analysis is mostly extracted from the European Commis-

sion’s AMECO database, including data on GDP, potential GDP and the public nances

(including structural balance and one off and temporary measures series). The AMECO data

underlying the Commission’ spring 2014 forecast is used.

Discretionary revenue measures are taken in AMECO from 2011 onwards, and from the

Output gap working group reporting before that year (Princen et al., 2013). The latter sample

starts in the early 2000s for most countries. For a few countries, the series starts at a later

date (see Annex B for details).

All in all, we have data that allow computing the discretionary scal effort over the past

decade (2004-2013) across 27 EU countries (Croatia is not included owing to lack of suf-

cient data).

3.1. Overall developments

The rst stylized fact is that the change in the structural (primary) balance tends to

yield an over-optimistic –i.e. more stabilizing than it really is− view of the scal stance in

booms, while it tends to underestimate the scal effort in recessions. This is mainly due to

the revenue windfalls/shortfalls (and to a lower extent to windfalls/shortfalls in unemploy-

ment expenditure) that show up as a consequence of the uctuations in tax (and unemploy-

ment) elasticities and by construction are part of structural balances. The discretionary

scal effort appears somewhat less exposed to these problems in that it relies on enacted

measures on the revenue side and on deviations from the medium-term potential growth

on the expenditure side.

71

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

Table 1

THE CHANGE IN THE STRUCTURAL PRIMARY BALANCE

AND THE DISCRETIONARY FISCAL EFFORT, 2004-2013

DFE (1)

Change in the structural primary

balance (2)

Difference (1)-(2)

Average

2004-

2007

Average

2008-

2010

Average

2011-

2013

Average

2004-

2013

Average

2004-

2007

Average

2008-

2010

Average

2011-

2013

Average

2004-

2013

Average

2004-

2007

Average

2008-

2010

Average

2011-

2013

Average

2004-

2013

BE -0.2 -1.2 0.0 -0.4 -0.4 -0.8 0.3 -0.3 0.3 -0.4 -0.3 -0.1

BG -1.2 1.7 0.3 0.1 -0.1 -0.8 0.4 -0.2 -1.1 2.5 -0.1 0.3

CZ 1.1 -0.1 1.8 1.0 0.8 -0.4 1.5 0.7 0.2 0.3 0.3 0.3

DK -0.4 -1.1 0.3 -0.4 0.3 -0.8 0.2 -0.1 -0.7 -0.2 0.1 -0.3

DE 0.6 -1.0 0.4 0.1 0.6 -0.5 0.8 0.3 0.1 -0.5 -0.4 -0.2

EE -1.6 2.2 0.0 0.0 -0.5 0.3 0.1 -0.1 -1.0 2.0 -0.2 0.1

IE -1.6 1.1 2.2 0.3 -0.7 -1.7 1.5 -0.3 -0.9 2.7 0.6 0.7

EL - - 5.8 - -0.6 0.0 3.1 0.7 - - 2.7 -

ES -0.7 -1.1 3.3 0.4 0.3 -2.5 1.9 -0.1 -0.9 1.3 1.4

0.4

FR -0.4 -0.6 1.1 0.0 0.0 -0.5 0.9 0.1 -0.4 -0.2 0.2 -0.1

IT 0.2 -0.3 1.9 0.6 0.5 -0.2 1.2 0.5 -0.3 -0.1 0.7 0.1

CY 0.6 -1.6 4.2 1.0 2.4 -2.8 1.1 0.4 -1.8 1.3 3.1 0.6

LV -1.6 4.9 0.5 1.0 -0.7 0.8 0.7 0.2 -0.9 4.1 -0.2 0.8

LT -1.9 1.0 1.6 0.0 -0.5 -0.1 0.8 0.0 -1.3 1.1 0.8 0.0

LU - - 0.2 - 0.2 -0.3 0.4 0.1 - - -0.1 -

HU - - -2.3 - 0.6 0.8 0.8 0.7 - - -3.1 -

MT 0.4 0.0 -0.3 0.1 0.7 -0.5 0.6 0.3 -0.2 0.4 -0.9 -0.2

NL 0.4 -0.9 1.7 0.4 0.1 -1.1 0.9 0.0 0.3 0.2 0.9 0.4

AT 0.0 -0.8 0.8 0.0 -0.3 -0.5 0.7 -0.1 0.3 -0.3 0.1 0.1

PL -0.3 -1.3

2.2 0.1 0.1 -1.6 1.5 0.0 -0.5 0.4 0.7 0.1

PT 0.2 -1.7 2.9 0.4 0.6 -1.6 2.4 0.5 -0.4 -0.1 0.4 0.0

RO -2.7 1.6 2.5 0.4 -1.1 -0.1 1.5 0.0 -1.7 1.7 1.0 0.4

SI -0.5 -1.1 2.4 0.3 -0.1 -0.6 1.1 0.1 -0.3 -0.5 1.3 0.2

SK 0.1 -0.8 1.7 0.3 -0.9 -1.0 2.0 -0.1 0.9 0.1 -0.3 0.3

FI -0.9 -2.0 0.2 -0.9 -0.2 -1.4 0.1 -0.5 -0.7 -0.6 0.1 -0.4

SE -0.1 -0.4 -0.4

1.2

1.4

-0.3

-0.1

0.2

0.4

-0.1

0.2

-0.5

-1.1

-0.8

-0.4

1.1

1.1

-0.1 -0.6 0.1

0.3

0.0

0.1

0.1

0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

UK -0.6 -0.7 0.0 -0.5

EA-17 0.0 -0.8 0.2 -0.2

EU-27 -0.2 -0.7 1.3 0.1 0.2 -0.8 1.0 0.1 -0.3 0.1 0.3 0.0

Source: AMECO (Commission Spring 2014 forecast), authors’ calculations.

Table 1 illustrates this aspect by comparing the discretionary scal effort and the change

in the structural primary balance by sub-periods.

7

In the boom period from 2004 until 2007

the difference between the two indicators is frequently negative, with the discretionary scal

effort showing a looser orientation of scal policy. This is most noticeable in several coun-

tries engaged in a boom and bust cycle (Bulgaria, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, Cyprus, Latvia,

Lithuania and Romania), where sizeable revenue windfalls were registered, jointly with

72

likely overestimations of potential growth. Similar albeit more limited effects can be ob-

served in other countries (including France and Italy). However, there is a diversity of coun-

try experiences, as this pattern of revenue windfalls associated with strong growth is not

found in a few other EU countries, most notably in Germany.

Following the outbreak of the crisis in 2008, sizeable stimulus packages were adopted

between 2008 and 2010 in a large majority of countries. This is generally captured by a

signicantly negative value of both indicators. However, in quite a few countries, there have

been at the same time signicant revenue shortfalls (see Figure 2) and large unemployment

expenditure increases going beyond average reactions. The concerned countries broadly

coincide with the group that experienced large revenue windfalls in the preceding period

(including Bulgaria, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania). In this

group, scal policy has been less supportive, based on the discretionary scal effort metric,

than would be inferred from reading only the structural balance. In fact, in the Baltic coun-

tries and in Bulgaria and Romania, policies were tightened according to the discretionary

scal effort, which is easier reconciled with the nancial tensions and adjustments under-

went by these countries over these years. Across the EU as a whole however, there is no

doubt that scal policy was considerably supportive of activity in this period. The discretion-

ary scal effort shows that the loosest scal stance was implemented in Belgium Denmark,

Germany, Spain, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and Finland. In these

countries, the cumulated degree of loosening over 2008-2010 reaches 3-6% of GDP accord-

ing to the discretionary scal effort.

Between 2011 and 2013 ambitious consolidation packages are adopted in most Member

States and accordingly both indicators unveil a generally tight scal stance. However, against

a context of severe economic slowdown the discretionary scal effort usually suggests a

tighter scal stance, particularly in the countries most affected by the boom and bust cycle

and under close market scrutiny. These countries include Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cy-

prus, Romania and Slovenia and to a lesser extent Portugal. Over 2011-2013, the average

annual degree of scal consolidation in these countries has exceeded 2% of GDP or even

signicantly more in some of them, according to the discretionary scal effort metric. In a

few economies however (including Germany in particular), the degree of adjustment sug-

gested by the discretionary scal effort is actually smaller than with the change in the struc-

tural balance.

Table 1 also shows that the discretionary scal effort and the change in the structural

primary balance broadly coincide on average for the period 2004-2013, though with signi-

cant variations across countries and time periods. In principle, it would be expected that the

differences between the two indicators are generally less pronounced in «normal times» than

they are at the present juncture. However, this assessment hardly applies to the pre-crisis

years. There are good reasons for not to qualify them as «normal times», but as «boom» ones

in view of the overheating in some Member States and the sizeable accumulation of imbal-

ances. These led to large revenue windfalls, the temporary nature of which was unveiled by

the crisis. In this connection, the discretionary scal effort would have helped better assess

the scal stance in good times as well.

73

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

3.2. Breakdown of the difference

The difference between the two concepts can be illustrated by the empirical distribution

of the gap between the two indicators (Figure 1). We nd that the distribution of gaps is well

centred, with means and medians very close to zero but a lot of dispersion around the mean.

The standard deviation of this distribution exceeds 1.5% of GDP, which seems quite large,

although admittedly the period of the sample relates to a particularly turbulent period and the

dispersion would likely be smaller if one were able to extend the sample to calmer times.

Overall the descriptive analysis conrms that while the two indicators are comparable, it

matters a lot at the frequency of annual budgets which one is looked at.

Figure 2 displays the contribution of the main explanatory factors of the difference be-

tween the change in the structural primary balance and the discretionary scal effort by

subsample. On average, positive revenue windfalls feeding the structural balance were reg-

istered annually during the expansionary phase up until 2007. However, this picture reverts

signicantly as of 2008. In most cases their size diminished remarkably, with the more vul-

nerable countries in fact registering sizeable revenue shortfalls. For the most recent years the

picture is more mixed, with some countries registering revenue windfalls while others show-

ing the opposite. However, the largest revenue shortfalls are registered in countries heavily

hit by the crisis and embarked in a protracted period of rebalancing and deleveraging.

Figure 1. Empirical distribution of the difference between the change

LQWKHVWUXFWXUDOEDODQFHDQGWKHGLVFUHWLRQDU\¿VFDOHIIRUW

Source: AMECO (Commission Spring 2014 forecast), authors’ calculations. The sample comprises 247 observa-

tions covering 27 EU countries over 2004-2013.

BE

BE

2004-2007 2008-2010 2011-2013 2004-2007 2008-2010 2011-2013

% GDP

Due to volatility of potential output

% GDP

Due to windfall unemployment expenditure

1.00

0.30

0.20

0.50

0.10

0.00

0.00

-0.50

-0.10

-1.00

-0.20

-1.50

-0.30

-2.00

-0.40

3.0

3.0

2.0

2.0

1.0

1.0

0.0

-1.0

0.0

-2.0

-1.0

-3.0

-2.0

-4.0

-5.0 -3.0

2004-2007 2008-2010 2011-2013

2004-2007 2008-2010

2011-2013

BG

CZ

DK

DE

EE

IE

BG

CZ

DK

DE

EE

IE

EL

EL

ES

ES

FR

FR

IT

IT

CY

CY

LV

LV

LT

LT

LU

LU

HU

HU

MT

MT

NL

NL

AT

AT

PL

PL

PT

PT

RO

RO

SI

SI

SK

SK

FI

FI

SE

SE

UK

UK

EA17

EA17

EU27

EU27

BE BE

BG BG

CZ CZ

DK DK

DE DE

EE

EE

IE IE

EL EL

ES ES

FR FR

IT IT

CY CY

LV LV

LT LT

LU LU

HU HU

MT MT

NL NL

AT AT

PL PL

PT PT

RO RO

SI SI

SK SK

FI FI

SE SE

UK UK

EA17 EA17

EU27 EU27

74

Albeit to a lesser extent, the volatility of potential output with respect to its medium-

term average growth is another major factor explaining the difference between the two in-

dicators. While its contribution is positive on average for the pre-crisis period, it turns

clearly negative as of 2008. The largest negative contributions between 2008 and 2010 are

registered in the Baltic countries and Ireland. However, in most of the remaining cases, the

contribution of this factor is largest between 2011 and 2013, especially in Greece, Spain,

Cyprus, Slovenia, and to a lesser extent, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, the Neth-

erlands and Portugal. It should be stressed, however, that the two notions of potential

growth coincide over time on average, so that there is no inherent bias in the discretionary

scal effort measure.

The contribution of windfall/shortfall unemployment expenditure is not as sizeable

as the former two other components. Leaving aside its size, its most remarkable feature

is that it is largely negative on average in the three subsamples. However, the most

negative values for this factor are registered after 2008 in Ireland, Greece, Spain, Cyprus

and the Netherlands and are associated to the intense job destruction observed in these

economies in recent years (beyond what would have been expected given growth de-

velopments).

Difference between the DFE and the change in the structural

% GDP

Due to revenue windfalls/shortfalls

% GDP

primary balance

4.0

4.0

Figure 2. Contributions to the difference between the change in the structural

SULPDU\EDODQFHDQGWKHGLVFUHWLRQDU\¿VFDOHIIRUW

Source: AMECO (Commission Spring 2014 forecast), authors’ calculations.

75

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

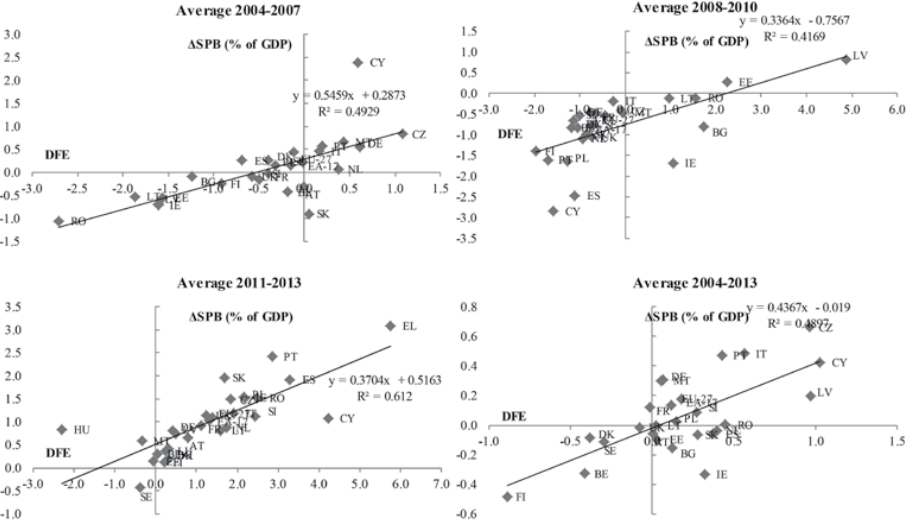

Figure 3. Relationship between the change in the structural primary balance

DQGWKHGLVFUHWLRQDU\¿VFDOHIIRUW

Source: AMECO (Commission Spring 2014 forecast), authors’ calculations.

Overall, the change in the structural primary balance and the discretionary scal effort

display notable correlation. For the entire sample the simple correlation coefcient amounts

to around 0.7. The correlation is stronger before the crisis period than thereafter, especially

between 2011 and 2013. In this period most of the countries adopt consolidation strategies

but the degree of scal tightening shown by the discretionary scal effort often exceeds that

stemming from the change in the structural primary balance (Figure 3). The correlation

between the two indicators also differs between the group of countries that underwent a

more pronounced boom and bust cycle (Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta,

Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia, Spain and the United Kingdom) and the group

gathering other economies. The correlation between the two indicators is signicantly

stronger in the latter group, than in the former group, suggesting that the information

brought by the discretionary scal effort is more signicant when economies experience

large shocks.

3.3. Discretionary scal effort and cyclical position

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the scal stance as measured by both the discretionary

scal effort and the change in the structural primary balance in relation with the economic

cycle for the euro area and for the EU-27. These charts allows a rough characterisation of

the scal path as either «pro-cyclical» (a positive scal effort in bad times, or a negative

76

effort in good times), «counter-cyclical» (the two opposite situations), or possibly close to

neutral. To do this requires some simplifying assumptions. In particular, we construct a

summary indicator of business conditions combining information from the level and the

change in the output gap

8

.

According to this approach, the scal stance as measured by the discretionary scal ef-

fort may be said to have been close to neutrality over the pre-crisis years of 2004-2007 in the

context of increasingly favourable conditions (in the detail, there was a modicum of initial

countercyclical tightening in 2004 in the euro area, and mild pro-cyclical loosening in the

mid-2000s for the EU-27). This suggests that overall the «good times» were not or not much

taken advantage of for strengthening budgetary positions. By contrast, the change in the

structural primary balance would suggest a countercyclical tightening taking place over the

same period.

With the «Great Recession» of 2008-2009 the scal stance changed gear dramati-

cally. The stimulus packages adopted to counter the effects of the pronounced recession

in 2009 led to a counter-cyclical scal loosening. However, as part of a strategy of

gradual consolidation amplied by the outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in the euro

area especially affecting several «peripheral» economies, most governments started to

implement signicant consolidation measures as of 2010. While this initially occurred

against the background of a mixed economy, as economies bottomed out of the recession

in 2010-2011, this strategy generally evolved into signicant pro-cyclical tightening in

2012-2013. The overall impression is that scal policies have been conducted in a some-

what stop and go and fashion, without much counter-cyclical action, except in the early

stage of the crisis.

77

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

)LJXUH 7KH¿VFDOVWDQFHDQGWKHF\FOH

Source: AMECO (Commission Spring 2014 forecast), authors’ calculations.

Despite some differences across countries, this picture is broadly observed in most coun-

tries, namely Belgium, the Czech Republic, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, the Netherlands,

Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland and the United Kingdom. Ireland shows a similar pat-

tern too, although the sharp pro-cyclical tightening took place in 2008, instead of 2009 as

observed in other cases, due to the earlier effects of the banking crisis derived from the

earlier collapse of the housing market. In turn, due to data availability we can only offer this

relationship for Greece for the period 2011-2013, when a pronounced pro-cyclical tightening

derived from the requirements of the macroeconomic adjustment programme is detected

9

.

4. Estimating scal multipliers

This section uses the natural properties of the discretionary scal effort as an indicator

of the scal stance to estimate, based on the panel data analysed in section 3, the short-term

impact on activity of scal policy, as well as its dependence on the composition of scal

shocks and the state of the economy.

4.1. Methodology

The most direct way to empirically evaluate short-term (1-year) scal multipliers is to

estimate the following specication:

y = m DFE + β y + Γ X + c + ε

(2)

it y it i it−1 i it i it

where y

it

is real annual output growth for country i and year t, X

it

is a vector of control fac-

tors, c

i

are country-xed effects, and m stands for the (one-year) output multiplier

10

.

y

78

The above specication is estimated for an unbalanced panel comprising 27 EU Member

States over the period 2004-2013, using the data presented in previous sections.

In multiplier regressions of this kind, a typical problem when relying on the structural

balance as an indicator of scal shocks, is the potential endogeneity to economic develop-

ments. This essentially stems from the large revenues windfalls and shortfalls associated

with good and bad times respectively, which induce a contemporaneous correlation between

changes in the structural balances and output growth that biases the estimated value of the

multiplier. In addition, the potentially pro-cyclical nature of potential growth is another pos-

sible source of endogeneity.

The discretionary scal effort is, by construction, much less exposed than the structural

balance to these endogeneity issues, because it relies on a bottom-up approach on the reve-

nue side, and because it uses a smoother notion of potential growth that is less likely to ex-

hibit pro-cyclicality. However, while that would make it a natural candidate to serve to

identify scal shocks in a multiplier regression, including using a basic OLS framework,

some degree of endogeneity in the discretionary scal effort through its reliance on smoothed

potential growth may remain.

Moreover, another potential source of endogeneity would arise if scal policy measures,

in particular revenue measures, responded contemporaneously to the prevailing economic

conditions (in other words, a systematic scal policy reaction function with contemporane-

ous growth entering as an argument). It is unclear whether such contemporaneous reaction

can be found empirically (see Born and Müller, 2012; Beetsma et al., 2009). However, there

is anecdotal evidence of this in at least occasional episodes, such as large counter-cyclical

response at the 2009 trough (see Section 3.3). In our case, neither the DFE nor its compo-

nents can be taken as exogenous to underlying economic conditions. To test this hypothesis

we run a set of Granger causality tests and in all cases the null hypothesis that GDP growth

does not Granger-cause the scal effort was rejected.

These problems advise against simple OLS estimates and call for a more robust estima-

tion strategy. Accordingly, we estimate alternative versions of equation (2) by GMM by using

the estimator proposed by Arellano and Bover (1995) and further developed by Blundell and

Bond (1998) for dynamic panel datasets, which offers consistent estimates.

11

We use the

typical GMM instruments for this estimator, namely the usual lagged levels and differences

of the dependent and DFE variables, and the levels and rst differences of the exogenous

variables included in the models. The validity of the instruments used is tested with the

Hansen J test.

The US GDP growth rate is included in all specications as a proxy for a wide range of

common economic factors, in particular extra-EU foreign demand. Moreover, we included a

monetary conditions index (mci). This index is obtained as a weighted average of the real

short-term interest rate and the real effective exchange rate relative to their value in a base

period

12

.

79

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

Furthermore, we also controlled for external scal shocks. In this regard, Beetsma et al.

(2008) and In’t Veld (2013) show that spillovers of scal shocks are large, which add to the

direct effects of domestic scal shocks on GDP. These effects are especially relevant when

some degree of coordination of scal policies takes place. Arguably, this has been the case

after the outbreak of the nancial and economic crisis since 2008. At earlier stages sizeable

stimulus packages were adopted by a number of Member States, whereas from 2010 on-

wards most countries engaged in scal consolidations. Accordingly, we included a country-

specic measure of external scal shocks gauged as the weighted average of the discretion-

ary scal efforts of other Member States. The weights used in this case were those of

national GDPs on total EU GDP.

4.2. Results

The scal multipliers obtained in the framework described above are shown in Table 2.

The average rst-year multiplier is estimated at around 0.75 (given lags, the second-year

multiplier is slightly above unity). Such values might be seen as relatively middle-of-the-

road, in comparison with previous empirical studies, although the evidence is quite dispersed

(see for instance Coenen et al., 2012; Barrell et al., 2012; or European Commission, 2012).

Our results are also broadly consistent with model-based simulations of the QUEST model

(see Roeger and In’t Veld, 2010, which also highlights the composition and state-dependen-

cy of the multipliers). Model (2) includes the lagged «discretionary scal effort» and its

components as regressors, but in no case were lagged scal shocks signicant.

The estimated coefcient of US growth is very high, at above one. While such a high

value may seem somewhat surprising, this coefcient is intended to capture not only direct

effects from US growth, but also the broad range of external factors affecting euro area

economies over the sample period, in particular during the crisis years. Finally, the monetary

conditions index is always non-signicant and this is the reason why it is removed from

model (3). Contemporaneous and lagged «external discretionary scal efforts» are included

in all specications, but only the latter turns out to be signicant in all specications, con-

rming the presence of some spill-over effects over the sample period, especially following

the outbreak of the crisis. The signicance of the lagged coefcient indicates that scal spill-

overs take some quarters to develop fully. As expected, the accumulated spill-over effect

captured by these coefcients is of lower magnitude than the direct effect stemming from

domestic scal shocks. In any case, the spill-over coefcients are remarkably high in all

specications, e.g. when compared with the results in In’t Veld (2013). This could be due to

strong spill-over effects in small Member States that that are not assessed in In’t Veld (2013)

in that it only focusses on a selection of countries.

Revenue and expenditure multipliers can be estimated by using as scal shocks the rev-

enue and expenditure sides of the DFE in isolation, i.e. the rst and second term, respec-

tively, of equation (2). Hence, our scal multipliers to revenue shocks are obtained in accord-

ance to a narrative approach. Conversely, by construction, expenditure multipliers gauged

80

with the DFE would be methodologically closer to those obtained under a top-down ap-

proach, albeit with renements as discussed earlier.

Both expenditure and revenue multipliers take the expected sign, although only ex-

penditure multipliers turn out to be signicant at conventional levels. First-year expenditure

multipliers are estimated at between 0.9 and 1.0, whereas revenue multipliers turn out to be

lower, at around 0.35 (with second-year responses always about a third higher).

Table 2

ESTIMATED OUTPUT MULTIPLIERS

dfe

t

dfe

t-1

drm

t

drm

t-1

dfe_g

t

dfe_g

t-1

y

t-1

y

US

t

mci

t

dfe*

t

dfe*

t-1

const

Obs.

Hansen test of overidentifying

restrictions

GMM (1)

-0.76***

(0.23)

0.32***

(0.07)

1.60***

(0.18)

0.02

(0.03)

0.29

(0.43)

-0.87***

(0.27)

-1.54***

(0.47)

219

χ

2

(36) =

24.82

GMM (1)

-0.35

(0.25)

1.02***

(0.32)

0.30***

(0.07)

1.53***

(0.20)

0.02

(0.03)

0.46

(0.43)

-0.95***

(0.29)

-1.48***

(0.51)

219

χ

2

(52) =

24.45

GMM (2)

-0.60**

(0.26)

0.16

(0.13)

0.35***

(0.06)

1.59***

(0.20)

0.01

(0.03)

0.28

(0.51)

-1.08***

(0.37)

-1.62***

(0.31)

213

χ

2

(51) =

25.21

GMM (2)

-0.22

(0.46)

0.08

(0.30)

0.81***

(0.22)

-0.18

(0.20)

0.35***

(0.06)

1.51***

(0.17)

0.01

(0.03)

0.40

(0.37)

-1.20***

(0.38)

-1.55***

(0.33)

213

χ

2

(72) =

22.76

GMM (3)

-0.75***

(0.23)

0.33***

(0.06)

1.59***

(0.15)

0.31

(0.41)

-0.90***

(0.26)

-1.47***

(0.27)

219

χ

2

(37) =

24.76

GMM (3)

-0.35

(0.24)

0.90***

(0.25)

0.33***

(0.05)

1.53***

(0.14)

0.34

(0.35)

-0.95***

(0.28)

-1.41***

(0.25)

219

χ

2

(53) =

23.76

Notes: Robust standard errors in brackets. The symbols ***, ** and * indicate that the coefcient is signicant at the

1%, 5% and 10% signicance levels, respectively.

Variables: dfe: discretionary scal effort; drm: discretionary revenue measures; dfe_g: discretionary effort on the

expenditure side; y: real GDP growth; y

US

: US real GDP growth; mci: the monetary conditions index; dfe*: country-

specic external DFE.

The estimated expenditure multipliers fall comfortably within the range of values ob-

tained in other empirical studies (see Romer and Bernstein, 2009; Christiano, et al., 2011; De

81

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

Castro, 2006; De Castro and Hernández de Cos, 2008; Giordano et al., 2007, among others).

In particular, expenditure multipliers are in line with those in Burriel et al. (2010) for the euro

area as a whole. In turn, although non-signicant, revenue multipliers seem also in accordance

with estimates in Biau and Girard (2005), Giordano et al. (2007), Perotti (2004) or Cloyne

(2011), whereas they are a bit lower than those in Burriel et al. (2010) for the euro area

13

.

Table 3

OUTPUT MULTIPLIERS IN BAD TIMES (∆YGAP<0)

GMM GMM GMM GMM

dfe*

t

-0.27

(0.29)

-0.29

(0.24)

dfe*bad

t

-0.81***

(0.31)

-0.81***

(0.29)

drm

t

0.04

(0.45)

0.07

(0.46)

drm*bad

t

-1.45**

(0.60)

-1.50**

(0.60)

dfe_g

t

0.71**

(0.28)

0.68**

(0.28)

dfe_g*bad

t

0.40

(0.34)

0.35

(0.38)

0.36***

0.37***

0.28*** 0.29***

y

t-1

(0.06)

(0.06)

(0.06) (0.06)

y

US

t

1.70***

(0.16)

1.69***

(0.15)

1.55***

(0.20)

1.53***

(0.18)

mci

t

0.02

(0.03)

0.02

(0.03)

dfe*

t

0.24

(0.42)

0.25

(0.41)

0.42

(0.40)

0.35

(0.41)

dfe*

t-1

-0.73**

(0.32)

-0.78***

(0.29)

-0.63**

(0.30)

-0.63**

(0.29)

const

-1.71***

(0.35)

-1.54***

(0.29)

1.49***

(0.47)

-1.31***

(0.29)

Obs. 219 219 219 219

Hansen test of overidentifying

χ

2

(35) = χ

2

(36) = χ

2

(50) = χ

2

(51) =

restrictions

25.56 26.69 20.52 21.43

Notes: Robust standard errors in brackets. The symbols ***, ** and * indicate that the coefcient is signicant at the

1%, 5% and 10% signicance levels, respectively.

There is a growing acceptance that output multipliers are higher in «bad times» than in

«good times». This can be for a number of reasons (see Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, 2011,

2012; Christiano, et al., 2011; Eggertson and Krugman, 2012; Blanchard and Leigh, 2013).

In particular, scal multipliers are deemed to be higher in an environment of weak activity,

lack of room for supporting monetary policy close to the zero lower bound and tight nancing

constraints for private agents. Conversely, in an economy without slack the effect of

82

expansionary spending policies are thought to be crowded out by lower private consumption

or investment.

To explore this idea, we take two different approaches: rst, we interact the «discretion-

ary scal effort» with a dummy capturing «bad times» that takes ones when the change in

the output gap is negative and zeroes otherwise

14

; second, we split the sample into «good

times» and «bad times» according to the same criterion and estimate separately

15

.

In the former case, Table 3 shows that the interaction between the «discretionary scal

effort» and the dummy variable capturing bad times is signicant in both specications and

contributes to increasing the scal multiplier. This effect stems mainly from the effect on the

revenue multiplier, whereas the interaction coefcient in not signicant in the expenditure case.

Table 4

OUTPUT MULTIPLIERS IN GOOD AND BAD TIMES

∆ygap≥0 ∆ygap<0

-0.71***

(0.27)

-0.63**

dfe

t

(0.31)

-0.59**

(0.28)

-0.70***

(0.23)

drm

t

-0.00

(0.55)

-0.09

(0.20)

-0.56

(0.40)

-0.55

(0.35)

dfe_g

t

0.96***

(0.28)

0.88***

(0.33)

0.91***

(0.35)

0.97***

(0.34)

0.29** 0.21* 0.30*** 0.30** 0.66*** 0.57*** 0.60*** 0.33***

y

t-1

(0.12) (0.11) (0.11) (0.13) (0.11) (0.11) (0.10) (0.05)

1.60***

y

US

t

(0.19)

1.62*** 1.56***

(0.20) (0.19)

1.57***

(0.17)

1.78***

(0.29)

1.74*** 1.82***

(0.25) (0.31)

1.80***

(0.25)

0.05

mci

t

(0.04)

0.04

(0.04)

-0.03

(0.12)

-0.05

(0.06)

0.39

dfe*

t

(0.43)

0.18 0.39

(0.44) (0.44)

0.48

(0.50)

-0.29

(0.51)

-0.21 -0.36

(0.28) (0.47)

-0.26

(0.37)

-0.42

dfe*

t-1

(0.53)

-0.29 -0.41

(0.48) (0.49)

-0.71

(0.68)

-0.60*

(0.36)

-0.67** -0.52*

(0.34) (0.28)

-0.64*

(0.34)

-1.05**

const

(0.51)

-0.96 -0.84*

(0.49) (0.45)

-1.06

(0.54)

-2.59***

(0.51)

-2.37*** -2.68***

(0.32) (0.40)

-2.46***

(0.33)

Obs. 125 125 125 125 94 94 94 94

Hansen test of overidentifying

χ

2

(32) = χ

2

(66) = χ

2

(33) = χ

2

(47) = χ

2

(30) = χ

2

(44) = χ

2

(33) = χ

2

(45) =

restrictions

23.22 24.25 23.88 23.92 24.85 23.02 25.58 22.83

Notes: Robust standard errors in brackets. The symbols ***, ** and * indicate that the coefcient is signicant at

the 1%, 5% and 10% signicance levels, respectively.

Table 4 presents output multipliers for «good» and «bad times» separately. Fiscal mul-

tipliers tend to be lower than average in good times, with revenue multipliers at around 0.1

and expenditure multipliers at 0.9. However, while differences in expenditure multipliers

83

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

are negligible (multipliers are estimated at between 0.9 and 1.0 in both cases), revenue

multipliers in bad times are increased to over 0.5, though remaining non-signicant at con-

ventional levels.

4.3. Caveats

The insights presented in this section are generally not overly surprising, but the esti-

mates have to be taken with care as they are based on a very short time span and accord-

ingly rely on a small number of observations.

Some other caveats should be borne in mind too. In general, the estimated magnitude of

scal multipliers signicantly depends on the composition of the scal shocks. The level of

granularity needed to account for the composition-dependency found in the literature goes

beyond the aggregate categories of expenditure and revenues used here. While in principle it

would be possible to break down further the discretionary scal effort, we do not attempt

such extension in this work because we do not have the necessary breakdown for discretion-

ary revenue measures.

Moreover, the multipliers presented above should be seen as average values over EU coun-

tries. They are calculated over twenty-seven countries enjoying differing characteristics and

expected responses to policy moves. Fiscal multipliers are generally thought to be somewhat

country-dependent and the panel approach can only deliver an average value. In an extension

to the basic specications reported above, we have tried to identify differences in multipliers

stemming from the degree of openness, one of the most-widely acknowledged origins of coun-

try differences (Barrell et al., 2012). Our results are in accordance with the assumption that

overall multipliers tend to decrease with openness, though the coefcients for the expenditure

or revenue components estimated separately are not signicant at conventional levels

16

.

It may also be worth recalling that one-offs and other temporary measures are netted out

to calculate the discretionary scal effort, for which the scal shocks used to estimate the

multipliers are either permanent or relatively long-lasting. As permanent scal shocks are

deemed to entail lower multipliers than transitory ones, the estimates presented here might

be downward biased when compared to other papers.

5. Conclusions

The comparison between the change in the structural primary balance and the discretion-

ary scal effort suggests that the former yields a more optimistic view of the orientation of

scal policy in booms, while it tends to underestimate the scal effort in recessions. Relying

on enacted measures on the revenue side and on medium-term potential growth on the ex-

penditure side, the discretionary scal effort seems to yield a better evaluation of the under-

lying orientation of scal policy when economies are exposed to shocks that are ill-captured

84

by standard estimates of cyclical tax and spending elasticities, large changes in interest pay-

ments, or sharp revisions in potential growth.

The empirical part of this paper conrms that the description of scal policies is to an

important extent inuenced by the choice of approach. In particular, the discretionary scal

effort suggests that, with exceptions, scal policy in the EU has been conducted in a more stop

and go and pro-cyclical fashion over the past ten years than suggested by traditional indica-

tors. In recent years, in a context when most EU countries are tightening scal policy, the

actual consolidation effort appears to be underestimated in many countries when assessed on

the sole basis of the structural balance. Conversely, during the booming years that preceded

the crisis, the structural balance tended to overestimate the progress on scal consolidation.

Using the discretionary scal effort, the average rst-year scal multiplier is estimated

at a below unity on average, with the aggregate expenditure multiplier being signicantly

larger than the aggregate revenue multiplier. We also nd some differentiation between good

and bad times as dened by a positive (respectively negative) change in the output gap, with

average multipliers being lower in the former case. Signicant limitations of our empirical

work, however, relate to the relatively limited time span, the uncertainty in parts of the data

(notably the yields of tax measures in early years of the panel), and the panel approach which

only allows us to estimate an average, non-country dependent multiplier.

85

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

Annex A. Analytical decomposition of the difference between the

change in the structural balance and the discretionary scal effort

17

To recall, the discretionary scal effort is dened as:

N

R

∆E − .

−

)(

pot E

R G

t

t t 1

DFE = DFE +DFE = −

(A.1)

t t t

Y

t

Y

t

with the N

R

budgetary impact of revenue measures in year t, E adjusted general government

t

expenditure adjusted and pot is medium-term nominal potential growth.

The structural balance is the cyclically-adjusted balance corrected for one-offs and other

temporary measures

18

:

R G

r

0

g

0

SB R G − S −1 − S −1 OG=−

( ) ( )

(A.2)

t t t 0 0 t

Y

0

Y

0

where R

t

and G

t

are general government revenues and expenditure respectively, both ad-

justed for one-offs and other temporary measures, BAL = R

t

is the general government

t

– G

t

balance, and OG is the output gap. The parameters ρ

0

r

and ρ

g

are the cyclical revenue and

t 0

expenditure elasticities. Equation (A.2) can also be written: SB = BAL – ε. OG

t

where

t t

r

0

g

0

ε =

(

ρ

0

−1

)

R

−

(

ρ

0

−1

)

G

is the semi-elasticity of the budget balance to the output gap

19

.

Y

0

Y

0

The change in the structural balance (ΔSB) can be decomposed into a contribution from

the revenue side (∆SBR) and a contribution from the expenditure side (∆SBG).

The revenue contribution can be expressed as:

∆

R

R R R

SB =

t t

−1

r

0

t

− −

(

S

0

−1

)

(OG

t

- OG

t−1

)

Y

t

Y

t

−1

Y

0

or equivalently

R

R

t

R

∆

t

−1

(

r

R

SB = − − S −1

)

0

Y

0

(

*

t

yy

t

-)

t

(A.3)

t

Y

t

−1

Y

0

where and denote the actual and potential GDP growth rates, respectively.

And the expenditure contribution is similarly:

G G

G

SB

G

∆ =−

t

−

t

−1

t

+

g

(

S

−

1

)

0

(yy-)

*

(A.4)

Y

0 t t

t

Y

t

−1

Y

0

86

On the revenue side:

The revenue contribution to the difference between and the DFE is the difference be-

R

R

N

t

tween expression (A.3) and

DFE

:

t

Y

t

R R N

R

R

R R

t t

−1

t

r

0

*

(A.5)

(

−

)

(--)∆SB − DFE = − − − S 1 y y

t t 0

t

t

Y Y Y Y

t t

−1

t

0

To give a simpler form to this expression, let’s dene the actual (i.e., observed, by contrast

to the average) semi-elasticity of revenues (after netting out discretionary measures)

S

t

r

as:

r

(

R

t

−

N

R

t

−

R

t−1

)

/ R

t−1

R

t

R

t−1

N

t

R

r

R

t

−1

S

t

=

, or equivalently

− −

=

(

S

t

−1

)

y

Y Y Y Y

(

Y −Y

) /

Y

t t−1 t

t

−1

t t−1 t−1

Plugging this expression into (A.5) and rearranging yields the following decomposition

for the difference between ΔSB and the DFE on the revenue side:

R R R

R

R R r r

0

r *

0

r

t−1 0

∆SB − DFE =

(

S −S

)

y +

(

S −1

)

y +

(

S −1

)

y

−

(A.6)

t t t 0 0 t t t

Y Y

Y

Y

0 0 t−11 0

The three terms in (A.6) have a clear economic meaning:

i. The rst term in the right hand side is an approximate measure of revenue windfalls/

shortfalls, which shows up as the difference between the actual and average elasticities.

Empirically, this is by far the largest contributor to the difference on the revenue side.

ii. The second term reects a possible inertial increase/decrease in the revenue-to-GDP

ratio linked in the event of a non-unitary (average) elasticity of revenues to output. In

general, this is small as most values of

S

0

r

do not much differ from unity.

iii. The last term is a residual term that appears when the actual share of expenditure

departs from the share in the base year. In practice, this is quantitatively small as well.

On the expenditure side:

The expenditure contribution to the difference between and the DFE is:

G G

G G I U

+SB

g G

t

−

t 1

g

+

t

− DFE

−

t

= −

(

S

0

−

1

)

0

−−

(

*

t

yy

t

t

Y

t

-

t

))+

t

−

Y

t

−1

Y

0

Y

t

G

t

−1

−

I

t

−

U

−+

(

1

pot

−1

t

−1

(A.7)

)

Y

t

87

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

Notice that in (A.7) total unemployment expenditure, instead of non-discretionary un-

employment expenditure is deducted. By rearranging terms (A.7) can be written as:

G G I ∆U I U

g G

t

−1

g

0

*

t t

t−1

+

t−1

∆SB − DFE = −y pot

)

+

(

S −1 (yy-)−∆ − − −

(

y pot

)

(A.8)

t t

(

0

)

t t

t

Y Y Y

YY Y

t

−1 0

t

t t−1

Similarly to what we did on the revenue side, the expression can be simplied by introduc-

ing the actual (i.e. observed, by contrast to the average) unemployment expenditure elasticity

(

U

t

−U

t−1

)

/ G

t−1

S

t

g

=

*

y

t

− y

t

g

*

G

Substituting in (A.8) and assuming that the term

S

)

t−1

t

(

y

t

− y

t

is at rst order equiv-

Y

t

alent to

S

g

(

y − y

*

t t t

)

the following expression after some algebraic manipulation is obtained:

∆SB

g

t

− DFE

G

t

=

(

S

g g

G

*

+

*

pot

)

G

−S

)

0

(y -)y

(

y −

t −1

I

−∆

t

0 t t t t

++

Y

0

Y

t−1

Y

t

(A.9)

G G

(

1

g

)

-)

*

+−S (yy

t−1

−

0

I +U

t t t

−

(

y

−

t−1 t−−1

t

pot

)

Y Y

t−1 0

Y

t−1

As in the case of revenues, the different terms in equation (A.9) have a clear economic

interpretation:

i. The rst term on the right hand side reects the «windfalls/shortfalls» in unemploy-

ment expenditure.

ii. The second term stems from the variability of potential growth, and reects the gap

between the usual «annual» potential growth and the smoother notion that we adopt

in the discretionary scal effort.

iii.The third one merely shows the effect of the increase in interest payment expendi-

ture. Such source of difference between both indicators is overcome by the use of the

change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance (∆SPB), instead of ∆SB.

iv. The fourth term shows up as due to the deviation of expenditure ratios with respect

to the xed weights used in the structural balance methodology.

v. Finally, the fth term reects the excess trend projection of interest and unemploy-

ment expenditure with respect to the medium-term potential growth rate.

As can be expected, the last two terms are small in practice when compared to the other

three ones.

88

Annex B. Discretionary revenue measures

Discretionary revenue measures can be dened as changes in policy that have a direct

impact on the revenues of general government. In general, a discretionary revenue measure

implies a legislative or administrative act, though there are some borderline cases.

20

Eco-

nomically, changes in public revenues can be split in two parts, one reecting the impact of

new discretionary measures, the other the «spontaneous» developments in the economy.

Such a decomposition is typically used when forecasting or analysing revenue developments.

Importantly, what should be accounted as the effect of a discretionary measure in a given

year is its «additional» impact in that year. A measure that is phased in (or phased out) over

several years therefore has successive incremental impacts over these years.

Figure B.1. Discretionary revenue measures, EU countries, 2004-2013

Source: AMECO, Output Gap Working Group, authors’ calculations.

Within the context of EU scal surveillance, growing attention has been paid in recent

years to the evaluation of discretionary revenue measures. In the framework of the Output

Gap Working Group of the Economic Policy Committee, Member States are asked to annu-

ally report data on discretionary measures on the basis of a common questionnaire (Princen

and Mourre, 2014). Recent efforts have focused on reaching a common denition of discre-

tionary measures, providing guidance on the reporting of complex measures, ensuring a

89

The Discretionary Fisical Effort: An assessment of Fiscal Policy and its Output Effect

comprehensive reporting (encompassing the whole general government, including in par-

ticular local governments and social security contributions), and encouraging Member

States to report data back from the early 2000s. The increased scrutiny of discretionary

measures for the purposes of scal surveillance, by the European Commission but also

potentially by national scal councils, acts as an incentive for Member States to improve

the quality and transparency of their reporting. This being said, there also remains room for

further progress in ensuring the robustness, full comparability, and public availability of the

estimates.

The available data point to a great variety of experiences with discretionary revenue

measures (Figure B.1). In a given year, both tax hikes and tax cuts are observed across the

group of EMU countries. However, there is a dominance of tax cuts in the pre-crisis period,

and also in the early phase of the crisis as governments embarked on stimulus packages, fol-

lowed by a large prevalence of tax increases in the ensuing consolidation period. On average

over the past decade, cuts and hikes tend to broadly offset each other’s, at least when taking

the EMU countries as a whole, with the panel average of measures at a mere 0.08% of GDP.

However, for individual years and countries, the size of revenue measures can be quite large,

sometimes exceeding 1% or even 2% of GDP in absolute value.

Notes

1.

Or the change in the structural primary balance. In the usual EU terminology, the structural balance is dened as

the cyclically-adjusted balance net of one off and other temporary measures. For a presentation and discussion

of the EU methodology, see Larch and Turrini (2009) and Mourre et al. (2013).

2.

This part of the paper expands on work presented in European Commission (2013).

3.

The aggregate elasticity of tax revenues to output is typically taken to be close to unity, although elasticities

of specic tax categories, such as personal income or corporate taxes, may differ signicantly. See Mourre et

al. (2014).

4.

The variable pot as set above is multiplied by GDP deator ination before entering equation (1), so that

the nominal growth of the expenditure aggregate E is benchmarked against a notion of «nominal» potential

growth.

5.

There are four differences between the discretionary scal effort and a literal reformulation of the ex-

penditure benchmark as an indicator of the scal stance: rst, the expenditure benchmark smoothens

public investment over four years; second the expenditure benchmark nets out government expenditure

programmes fully matched by revenues from EU funds; third, to relate nominal expenditure and real

potential growth, the expenditure benchmark employs the average of the GDP deator ination forecasts

for year t made by the Commission in spring and autumn of year t-1, while the discretionary scal effort

uses the actual GDP deator ination; fourth, the discretionary scal effort corrects for one-offs and other