University of Richmond University of Richmond

UR Scholarship Repository UR Scholarship Repository

Robins Case Network Robins School of Business

2-2020

Uber Uber

Jeffrey S. Harrison

University of Richmond

Bryant Holden

Kelli McKenna

Scott McQuiddy

Alex Wiles

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/robins-case-network

Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, and the Strategic

Management Policy Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Harrison, Jeffrey S., Bryant Holden, Kelli McKenna, Scott McQuiddy, and Alex Wiles.

Uber.

Case Study.

University of Richmond: Robins School of Business, 2020.

This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Robins School of Business at UR Scholarship

Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robins Case Network by an authorized administrator of UR

Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Uber

February 2020

Written by Jeffrey S. Harrison, Bryant Holden, Kelli McKenna, Scott McQuiddy, and Alex Wiles at

the Robins School of Business, University of Richmond. Copyright © Jeffrey S. Harrison. This case

was written for the purpose of classroom discussion. It is not to be duplicated or cited in any form

without the copyright holder’s express permission. For permission to reproduce or cite this case,

contact Jeff Harrison at [email protected]. In your message, state your name, affiliation

and the intended use of the case. Permission for classroom use will be granted free of charge.

Other cases are available at: http://robins.richmond.edu/centers/case-network.html.

1

In 2015 an article in the Wall Street Journal declared: “There’s an Uber for everything now.”

1

The article was referring to the profusion of on-demand services available to consumers. Since

then the company continued to expand into new business areas. As of 2020, the company was

engaged in ride-hailing, food delivery, freight, and micromobility, offering rides to users through

dockless e-bikes and e-scooters.

2

As CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said in an open letter published on

Uber’s website in April 2019, the company was “still barely scratching the surface when it

comes to huge industries like food and logistics, and how the future of urban mobility will

reshape cities for the better.”

3

Dara left Expedia in 2017 to become Uber’s CEO in the wake of substantial internal conflict that

erupted under Uber founder and CEO Travis Kalanick. There was much still to do to rehabilitate

a corporate culture in light of accusations of discrimination and sexual harassment. There were

also some serious issues to settle with respect to the status of Uber drivers as employees or

private contractors, not to mention the troubling performance of the company’s stock after its

IPO in May 2019. How could Dara ensure Uber’s movement toward profitability, revitalize the

company’s culture, and rebuild its public image?

UNDERSTANDING UBER

Uber “sets the world in motion” through connecting individuals by way of its app-based

platform, which is operational in over 63 countries and 700 cities globally.

4

Uber, rooted in

connectivity, operates through relationships with customers and drivers. Customers, or riders,

utilize the Uber app to hail rides, request food delivery, freight ship items, and reserve personal

mobility devices. Drivers utilize the app as independent contractors, using their own personal

vehicles to taxi customers or deliver food on behalf of participating restaurants.

Uber Culture

In November 2017, just months after Dara Khosrowshahi became Uber’s CEO, a document

outlining was released that explained Uber’s culture. It explained: “These norms preserve the

best of the founding Uber culture that built one of the world’s most valuable and important

companies, while recognizing that we must adapt to become a great company where every

person feels respected and challenged, can contribute in his or her own way, and learn and grow

as an individual and as a professional.

• We build globally, we live locally. We harness the power and scale of our global

operations to deeply connect with the cities, communities, drivers and riders that we

serve, every day.

• We are customer obsessed. We work tirelessly to earn our customers’ trust and business

by solving their problems, maximizing their earnings or lowering their costs. We surprise

and delight them. We make short-term sacrifices for a lifetime of loyalty.

• We celebrate differences. We stand apart from the average. We ensure people of diverse

backgrounds feel welcome. We encourage different opinions and approaches to be heard,

and then we come together and build.

• We do the right thing. Period.

2

• We act like owners. We seek out problems and we solve them. We help each other and

those who matter to us. We have a bias for action and accountability. We finish what we

start and we build Uber to last. And when we make mistakes, we’ll own up to them.

• We persevere. We believe in the power of grit. We don’t seek the easy path. We look for

the toughest challenges and we push. Our collective resilience is our secret weapon.

• We value ideas over hierarchy. We believe that the best ideas can come from anywhere,

both inside and outside our company. Our job is to seek out those ideas, to shape and

improve them through candid debate, and to take them from concept to action.

• We make big bold bets. Sometimes we fail, but failure makes us smarter. We get back

up, we make the next bet, and we GO!

5

The New York Times described the new set of core values under Khosrowshahi as “something

of a repudiation of the culture created under (previous CEO) Kalanick,” noting that the

company’s previously aggressive nature has led to business challenges serious enough to

threaten the company’s ability to operate in certain markets, including London.

6

Under Kalanick, Uber’s mission had been to “make transportation as reliable as running water,

everywhere, for everyone.”

7

Under Khosrowshahi’s leadership, the mission had transformed to

“ignit[ing] opportunity by setting the world in motion.” Uber’s website follows its mission with

the assertion that:

Good things happen when people can move, whether across town or towards their

dreams. Opportunities appear, open up, become reality. What started as a way to tap a

button to get a ride has led to billions of moments of human connection as people around

the world go all kinds of places in all kinds of ways with the help of our technology.

8

Business and Strategies

Uber uses its technology platform for a variety of business purposes including ridesharing, food

delivery, personal mobility, and freight services. Uber’s largest business area is its “Rides”

segment, which includes the revenue it earns from its ridesharing platform and through leasing of

vehicles to third parties. The “Rides” segment accounted for over 75% of Uber’s reported

revenue in 2019. Uber’s second largest business area is its “Eats” segment, which earns revenue

through transactions on its UberEats platform via meal delivery services. The “Eats” segment

accounted for roughly 18% of Uber’s reported revenue in 2019. Collectively, Uber’s other

business areas, such as “Freight,” account for about 5% of the company’s revenue.

While Uber’s global headquarters is located in San Francisco, California, it operates many

regional offices around the world to support the cities and countries in which its services are

available. The company currently offers its services in the United States, Canada, Latin America,

Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia. In 2019, over 60% of Uber’s revenue came from

transactions in the United States and Canada. The next largest region in terms of revenue is the

combination of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, which contributed roughly 15% of Uber’s

revenue in 2019.

9

3

Since Uber’s inception in 2009, the company has drastically expanded beyond the simple

concept of “tap a button, get a ride.” While its ridesharing services still account for the prominent

portion of Uber’s business, the company has aggressively invested in diverse industries where it

believes it can leverage its technology to create value, including food delivery, logistics, and

urban mobility. Moreover, the company expresses a strong desire to continue growing its core

business, often citing that Uber “accounts for less than one percent of all miles driven

globally.”

10

Uber cites nine “key elements of [its] growth strategy, including:

• Increasing Ridesharing penetration in existing markets;

• Expanding Personal Mobility into new markets;

• Continuing to invest in and expand Uber Eats;

• Pursuing targeted investments and acquisitions;

• Leveraging [its] platform to launch new products;

• Increasing Driver and consumer engagement;

• Continuing to invest in and expand Uber Freight;

• Continuing to innovate and transform [its] products to meet platform user needs; and

• Investing in advanced technologies, including autonomous vehicle technologies”

11

Uber initially launched its services in the United States in 2010, but quickly expanded to Europe,

Australia, Latin America, India, Asia, the Middle East and Africa by 2013. Uber continued to

launch variations of its ridesharing services, introducing UberX in 2012 and UberPOOL in 2014.

In 2015, Uber began to strategically invest in areas like autonomous vehicles with its ATG

Launch in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania (US). In 2016, the company introduced the Uber Eats app and

launched Instant Pay while boasting completion of 1 billion trips. In its most recent history

leading up to its initial public offering, Uber began aggressively expanding its platform. In 2017,

the company launched Uber Freight and expanded Uber Eats to over 200 cities. The following

year, Uber launched Uber Pro, Express POOL, Uber Rewards, and Uber Cash. In 2017, the

company acquired JUMP and launched New Mobility (dockless e-bike and e-scooter business).

In March 2019 the company acquired its competitor in the Middle East, Careem, for $3.1 billion.

Careem operates in 120 cities across 15 countries, offering its internet platform for mobility,

delivery, and payments.

12

PEOPLE

Top Management

Travis Kalanick, Co-Founder and Former CEO

Travis Kalanick became CEO of Uber in 2010, four months after its launch, when service was

only offered in San Francisco. He had entrepreneurial experience from two previous ventures

and a track record for raising significant capital for start-ups. However, as Uber grew, his tenure

was plagued by a series of highly public conflicts that eventually led to his ouster.

4

On the heels of the presidential election of Donald Trump, Kalanick secured a seat on the

President’s technology council, an association with which many Uber employees expressed

dissatisfaction. On January 29, 2017, Trump instituted a travel ban targeting Muslims, sparking

protests at many airports, including JFK International Airport in New York. Uber turned off

surge pricing in the area of the airport, which many members of the public interpreted as an

attempt by Uber to profit off of the ban and protests. A digital #deleteUber campaign resulted in

at least 500,000 users deleting their Uber accounts in the span of days, not counting users who

only deleted the app without deleting their accounts. Mike Isaac, a journalist who has covered

Uber extensively, suggested that “to #deleteUber wasn’t just to remove a ride-hailing app from

one’s phone. It was also to give a giant middle finger to greed, to ‘bro culture,’ to Big Tech—to

everything the app stood for.”

13

Kalanick resigned from Trump’s council shortly thereafter.

14

On February 19, 2017, a former Uber employee, Susan Fowler, wrote an extensive blog article

that documented her “one very, very strange year at Uber,” during which, on her first day of

work, she claimed she was sexually harassed by her direct supervisor over the company’s instant

messaging app, uChat. Despite her immediate report of this incident to human resources staff,

the supervisor in question was not reprimanded or fired. Instead, Fowler was encouraged to look

for another team to join within the company. She did so, but also began to hear accounts from

other female employees which suggested that sexual harassment and discrimination were more

widespread at the company than her experience initially suggested. Fowler’s blog post

encouraged current and former employees to step forward with their complaints of a similar

nature. Many upset Uber employees subsequently left and found work with companies like

Airbnb, Facebook and Uber’s direct competitor, Lyft.

15

On February 28, Kalanick was caught on camera yelling at an Uber driver who complained about

changes in Uber’s fee structure. The footage circulated widely in the media. By June 21, 2017,

Kalanick had resigned as Uber’s CEO, but remained on the company’s board.

Dara Khosrowshahi, Current Uber CEO

Kalanick was replaced by Dara Khosrowshahi, who previously served as CEO of online travel

website Expedia for 12 years. Expedia’s holdings include Hotels.com, Trivago, and Travelocity,

all of which operate as online travel booking sites. Prior to leading Expedia, Khosrowshahi

served as the chief financial officer of IAC, a conglomerate of “various consumer-facing online

businesses, including video-sharing website Vimeo, the Daily Beast, Investopedia, and Match

Group’s brands including Match and Tinder.”

16

IAC purchased Expedia in 2003 and placed

Khosrowshahi at the helm in 2005. Since then, Expedia’s stock price increased 500%, with much

of the company’s growth stemming from acquisitions, including that of Orbitz for $1.6 billion in

2015.

17

Having emigrated from Iran as a child, Khosrowshahi graduated from Brown University with a

background in engineering, self-describes as a “sci-fi geek,” and generally maintained a low

profile during his time at IAC and Expedia.

18

Those who know him describe him as “what you

see is what you get,” “a person of substance,” and “very steady,” and he has not been shy about

commenting on matters of immigration or criticizing President Donald Trump for failing to “rise

to the expectations of his office.”

19

5

Despite his strong professional performance and relatively noncontroversial standing in the

technology industry, Khosrowshahi was the third choice of Uber’s board of directors in a highly

contentious selection process for Travis Kalanick’s replacement. He landed the role only after

Hewlett Packard Enterprise CEO Meg Whitman withdrew her name from consideration and

General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt was eliminated over concerns about his company’s recent

stagnation.

20

Much of the first two years of Khosrowshahi’s time at Uber was spent on an

“apology tour” to repair relationships with drivers and cities across the globe.

21

Biographical briefs of other company executives can be found in Exhibit 1.

Board Leadership

The discord among Uber’s board of directors leading up to Khosrowshahi’s appointment in

August 2017 was followed in September by former CEO Travis Kalanick’s unilateral

appointment of two new directors: Ursula Burns, former CEO of Xerox Corp., and John Thain,

the ex-leader of Merrill Lynch.

22

Just a month later, the board approved governance changes

offered by Khosrowshahi and Goldman Sachs, an Uber investor. The changes resulted in the loss

of special voting privileges for shareholders, including Kalanick.

23

According to the New York

Times, this change “paved the way for a sale of some stock to the Japanese conglomerate

SoftBank and for the company to go public by 2019.”

24

A full board roster is included in Exhibit

2, and a brief on Uber’s major investors can be found in Exhibit 3.

Employees

During Travis Kalanick’s tenure, Uber presented the quintessential image of an up-and-coming

tech giant: a work-hard, play-hard culture where long hours were expected. Kalanick gave

employees a great deal of latitude in conducting business, which made sense for a global

business establishing footholds in a wide variety of locales. However, since instinct drove many

of his hiring decisions, Kalanick led a fairly homogenous company—predominantly young,

white, and male.

25

Employee evaluations were “problematically arbitrary,” with minimal

required justification from managers. Since employees were evaluated against the company’s

core values, it was possible to receive a poor evaluation for “lack of ‘hustle.’”

26

Even more

problematically, Uber offices worldwide were rife with aggressive behavior, sexism and abuse,

often in a party environment fueled by alcohol and drug use. In Thailand, a female employee

abstaining from drug use complained that she was pushed facedown onto a table by her manager

and forced to inhale cocaine.

27

Apparently, the promise of personal success that would come

from the company’s growth pushed many to “white-knuckle it through the bad times.”

28

A blog post published in February 2017 by a former Uber employee, Susan Fowler, publicly

belied Uber’s systemic discrimination and harassment. Her account of being sexually harassed

on her first day with the company and subsequently having her complaints dismissed by

superiors were echoed by many employees. Ultimately, Uber had to engage more than one law

firm, including that of former Attorney General Eric Holder, to investigate and make

recommendations in response to at least 215 complaints.

29

6

Drivers

Writer and journalist Adam Lashinsky documented the ease with which he signed up to become

a driver in his book Wild Ride. It took 15 minutes to submit basic information and authorization

for a background check online. Lashinsky then took his car to his local Uber inspection center

where his vehicle received a “cursory once-over” to check basics like seatbelts and taillights. The

Uber representative “verified [his] auto insurance and vehicle registration, helped [him]

download the rider app onto [his] phone, and issued [him] a permit to display in [his] window

when [he] picked up or dropped off at local airports.”

30

By the time Lashinsky left with his

welcome packet of Uber logo stickers for his car, approximately one hour had passed since he

started the process.

31

As easily as one can begin working as an Uber driver, one can stop – one

study found that one in six app-based gig workers “is new in a given month, and more than half

of participants quit within a given year.”

32

In the period from January 2015 through March 2017, Uber reported 1,877,252 people who had

driven through UberX or UberPOOL in 196 cities; many drivers work for more than one

platform, including Uber’s competitor, Lyft.

33

Many drivers were immigrants from developing

countries who were willing to work extremely long hours for relatively low pay.

34

An analysis in

2015 found that “51 percent of Uber drivers work one to 15 hours per week, 30 percent work 16

to 34 hours per week, while 12 percent work 35 to 49 hours per week, and 7 percent work 50

hours or more per week.”

35

This does not account for hours worked through other platforms. One

study of Uber’s driver population categorized drivers as one of the following:

• Hobbyists (casual gig workers)

• Part-time drivers, who may value “income during career transitions,” flexibility, or a

“good bad job” due to “a criminal record or limited education”

36

• Full-time drivers, some of whom even lease expensive luxury cars to participate in

uberBlack or uberSUV, who “used to make money, before rate cuts that Uber

implemented in January 2017”

37

A 2016 Pew Research Center survey reported that 56 percent of surveyed gig workers financially

rely on gig work income, while 42 percent considered themselves “casual” gig workers who

“report that they could live comfortably” without the income from gigging.

38

The variation in

drivers’ reliance on gig income does cause friction among drivers. Since part-time drivers and

especially hobbyists are less reliant on this income, they can “function a bit like scabs,” or

workers who step in to do the work of striking laborers, in the eyes of “occupational drivers

trying to support their families.”

39

Rider ratings serve as the primary means of drivers’ performance evaluation. Through the Uber

app, riders rate their drivers after the completion of the ride. While this system supports

efficiency through “the semi-automated management of large, disaggregated workforces,”

researchers have questioned the implications of this approach.

40

One concern is that the implicit

biases that riders may have against some groups based on race, gender, age, or other factors may

influence ratings, which could in turn influence employment decisions by management.

41

7

A nine-month study identified “information and power asymmetries” as a result of the Uber app

are “fundamental to its ability to structure control over [Uber’s] workers.”

42

Some drivers have

speculated that Uber’s algorithm “rewards drivers implicitly for following behavioral

prompts…although the explicit dispatching rule is that passengers are matched with the nearest

driver.”

43

Uber does not directly supervise drivers, instead offering suggestions and recommendations

through the app, leading with phrases like “riders give the best ratings to drivers who…”

44

Critics argue that the degree of indirect control that Uber exerts over drivers negates the firm’s

assertion that drivers are “independent contractors and entrepreneurs,” in that they are expected

to “deliver a standardized experience to passengers or risk suspension, deactivation, or loss of

pay.”

45

Some problems with drivers are more serious, including reports of “physical assault, kidnapping,

sexual assault and rape” in at least seven countries including the United States, some of which

involved drivers who were known felons who managed to pass Uber background checks.

46

Generally, Uber has argued that it has no liability because drivers are independent contractors.

47

CHANGES UNDER KHOSROWSHAHI

Since the departure of Kalanick, Uber has worked to evolve its culture and workplace

environment.

Diversity and Inclusion

Just days before Kalanick’s resignation from Uber in June 2017, board member David

Bonderman also resigned after making a sexist joke at a company-wide meeting convened to

address allegations of sexual harassment at the company.

48

As Khosrowshahi took the helm, he

hired the company’s first chief diversity officer, Bo Young Lee, and reviewed salaries of all

employees to ensure fair pay.

49

In March 2018, Uber settled a $10 million class action suit filed by 400 current and former

employees who were women and people of color. The suit claimed that these employees had

been “passed over for promotions and were paid less than other workers for doing the same job,

and that managers had created a hostile work environment.” In addition to payment, settlement

also required a promise from the Uber to “revamp pay practices and provide mentoring to female

employees and workers of color.”

50

In July, Uber’s human resources director, Liane Hornsey

resigned, and was replaced by Nikki Krishnamurthy in October. Like Dara Khosrowshahi,

Krishnamurthy came to Uber from Expedia, where she had headed human resources.

Uber’s Diversity and Inclusion report for 2019 highlighted specific goals that had been

integrated into executive performance evaluations and compensation. For several senior leaders,

these goals included increasing the proportion of women and underrepresented employees above

35% and 14%, respectively, at specified organizational levels by 2022.

51

To support these goals,

Uber’s human resource systems were modified to include improved manager training and efforts

to reduce bias in interview processes. Other tools deployed included diversity scorecards and

8

diversity and inclusion audits. The company also piloted a variety of “sponsorship” models to

cultivate and support emerging talent in its technology and operations business units. Uber then

scaled these efforts to implementation across the entire company to “[ensure] that historically

underrepresented talent is supported and that our leaders are learning new skills to become better

champions for diversity.”

52

From 2018 to 2019, Uber made some documentable progress toward a more diverse workplace.

The population of female employees increased 42.3%, and in the United States, the population of

black employees grew 44.5%, while the population of Latin employees grew 73.5%. In all cases,

Uber reported that this growth was “most notable” in its technology business unit.

53

Employee Education

Uber has begun offering opportunities for continuing education to both corporate employees and

drivers. In partnership with Harvard Business School Online, Uber offers corporate employees

who are “current and aspiring leaders” access to executive education courses focused on

“culture, leadership and inclusion.”

54

The company has also initiated partnerships to help hone

the technological, engineering, and entrepreneurial skills of college students and recent college

graduates, particularly women and people of color; this also serves to identify and cultivate

potential Uber hires.

Uber’s first efforts to provide drivers access to continuing education began in the United

Kingdom through a program called Level Up, which it claims is “the first education program

solely dedicated to developing job skills for those working in the gig economy.”

55

Currently, the

program offers 300 online courses and 30 degree-level scholarships to Uber Eats delivery

partners. In the United States, the company has partnered with Arizona State University online

“to provide eligible drivers, delivery partners or their families the opportunity to complete

courses toward an undergraduate degree or non-degree certificate…with tuition fully covered,”

and with the stated goal of scaling this kind of program globally.

56

Business Practices

Uber’s business conduct guide was made publicly available through its website in November

2019. The document outlines guidelines for ethical decision-making and behavior for Uber

employees. The language throughout the guide emphasizes doing the right thing, creating an

inclusive work environment, respect for privacy, and respectful, ethical interactions with

business partners, competitors, regulators, and government representatives.

57

As with many large

companies, Uber has a “war room,” a physical space at its headquarters that serves as a center for

strategy, particularly with regard to competitors. In 2019, one author reported that Uber’s war

room, which was previously “used to combat archrival Lyft and camouflage its operations from

the eyes of transportation regulators, was recently renamed the ‘peace room’” in light of the

company’s negative publicity.

58

In 2018, Uber announced mandated six-hour driver breaks, a policy similar to that used by taxi

commissions.

59

To address issues related to driver-instigated violence, Uber has added a “panic

button” to the version of its app available in the United States.

60

9

Employee Response

In January 2019, an Uber employee survey conducted in October 2018 was leaked to the press.

This iteration of the 35-question semi-annual survey was completed by 18,648 employees. While

many questions on the survey showed in an increase in positive responses for most questions, a

few questions directly related to workplace culture did not. Survey results are included in Exhibit

4.

61

INSIDE UBER

Communications

For internal corporate communications, Uber previously relied on an app called HipChat. In

2019, it was reported that Uber had launched a proprietary chat app called uChat, which was

developed in response to problems the company encountered with HipChat in handling the

volume of messages employees sent on a daily basis. uChat reportedly has the ability to handle

70,000 simultaneous users and send up to one million messages daily.

62

While Uber can communicate with drivers directly through its app, drivers do not have an

official means of communicating with one another. Instead, drivers who do connect with one

another for “workplace culture and information-sharing” reach each other through online forums;

since drivers in forums can log on from any number of locations, there is “no centralized local

basis for worker organization or power.”

63

Uber’s direct communication with drivers has in some instances taken the form of print

periodicals. The first publication, called Momentum, launched in 2015 and focused on helpful

tips for drivers, such as how to exercise behind the wheel.

64

A new publication, Vehicle,

launched in 2018 that focused primarily on drivers’ stories, their reasons for driving and the

communities in which they live. Vehicle also had a web-based presence. Both publications

focused print distribution to a few specific major cities in the United States.

65

Marketing

Uber markets its service both to drivers and riders and uses geographic segmentation to version

its app and marketing messages for specific countries like India, China, and the United Kingdom.

For example, a United Kingdom-based campaign highlighted the various uses of Uber, while in

India, a 2016 “Moving Forward” campaign aimed to “demonstrate how freedom of mobility

could provide both drivers and riders alike a higher standard of living” through billboards, print

advertising, and digital films.

66

After the debut of the digital film series, approximately 50,000

individuals signed up as Uber drivers.

67

After the hiring of Khosrowshahi as CEO in 2017, Uber launched a different “Moving Forward”

campaign that sought to highlight the company’s revitalized culture and promise to do the right

thing. A year later in 2018, the company launched a campaign called “Doors are Always

Opening” that relied on digital and outdoor media. According to Uber’s executive creative

10

director, Paulie Dery, the message of the “purely emotional” campaign was that “opportunity

happens everywhere if you are willing to move…We've always had a certain amount of hustle

and belief that movement creates something better for everybody, and that's really at the center

of the idea.”

68

Operations

Uber’s primary business are design, engineering, operations, and product.

69

Its operations have

been challenged by conflict with partners and regulators. For example, under Kalanick, Uber

actively attempted to deceive Apple about a component of its app’s coding that would

circumvent user privacy. Apple detected this deception and a series of tense conversations

among the two companies’ leadership ensued before the issue was resolved.

70

Part of Uber’s conflict with regulators and government agencies is that its business model does

not fit with regulations that govern traditional taxi businesses. This has led to attempts on Uber’s

part to directly or indirectly influence such regulations. Uber’s domestic lobbying efforts have

involved “nearly 400 paid lobbyists across forty-four states; the number of ride-hailing lobbyists

outnumbered the paid lobbying staffs of Amazon, Microsoft and Walmart combined.”

71

In

Philadelphia, the firm faced a $12 million fine for 120,000 violations of transit code for

operating illegally, a matter eventually settled for $3.5 million.

72

Internationally, Uber failed to legalize its uberPOP service in the Netherlands, which some

researchers ascribe to the firm’s continued operations while concurrently lobbying for revised

regulation.

73

In 2017, the United States Justice Department began an examination of allegations

that Uber violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act through payment of bribes in foreign

countries to operate its ride-hailing service. In April 2019, this process had yet to reach

resolution as noted in filings related to the company’s impending IPO.

74

In Arizona in March 2018, a self-driving Uber vehicle hit and killed a pedestrian. Just months

into his leadership of the company, Khosrowshahi halted the firm’s autonomous vehicle

operations. In a public statement, he reflected on the incident, stating that, “if you think about us

as a transportation platform, then our number one priority this year is standing for safety…We

have to stand for the content of our platforms. That means we have to know who our drivers are

and we have to be open and fair. We can't just say we're a platform and our job is done."

75

Autonomous vehicle operations resumed in some cities before the end of 2018.

Data Management

In order to provide its services, Uber collects a variety of data on drivers and riders, including

user movement, drivers’ license and insurance information and riders’ contact and payment

information. Internally, a mechanism for employees to track the movement of riders was called

“god view,” but was later renamed “heaven view.”

76

This data was necessary to the delivery of

service, though one journalist expressed surprise over “how loosely Uber restricted internal

access to the tool.”

77

11

Uber also leveraged its data to track those who might threaten the firm’s operations in a

particular locale through the use of “Greyball.” This feature was “a snippet of code affixed to a

user’s Uber account…that identified that person as a threat to the company. It could be a police

officer, a legislative aide, or…a transportation official.”

78

If a user had their account flagged in

this manner, they could only view a falsified version of the app “populated with ghost cars.”

79

In September 2016, Uber experienced a data breach affecting the data of 57 million customers,

including names, email addresses and phone numbers. The information of about 7 million drivers

was also accessed, including 600,000 United States driver’s license numbers. Under Kalanick,

Uber paid $100,000 to the hackers at the direction of Chief Security Officer Joe Sullivan in

exchange for the deletion of the stolen data. Funds were routed through Uber’s “bug bounty

program,” which was intended to work with friendly hackers to expose weaknesses in

technological assets. The per-bug payout limit for that program was $10,000. Though Kalanick

received news of this breach in November 2016, this intrusion was made public a year later after

Khosrowshahi became CEO. This delay violated California laws that required notification “in

the most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay.”

80

Khosrowshahi made public

statements about the hack and its resolution after he learned of it. He also fired Sullivan and one

other employee.

81

Financial Status

Uber’s initial public offering in May of 2019 was highly anticipated by investors; however, it has

now made its mark as the “worst first-day performance for a giant U.S. IPO by a wide margin”.

Shares of Uber’s stock ended its first day down $3.40, or 7.6% from its offering price of $45.

82

Share price continued to drop roughly 30% from May 2019 to November 2019, with shares

priced at $31.08 as of November 4, 2019. In the third quarter of 2019, Uber generated $3.8B in

revenue, up 29.5% from the previous year. Costs and expenses for the third quarter of 2019

totaled $4.9B, leaving Uber with an operating loss of $1.1B. Uber’s financials are found in

Exhibits 5, 6, and 7.

THE EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

Rise of the Gig Economy

The modern version of the term “gig economy” can be traced back to 1996 with the launch of

Craigslist, but began to garner mainstream attention around the 2008 financial crisis in the

United States.

83

Independent contracting and short-term labor is nothing new, but the huge

investments made by early adopters of the business model, including Uber, are most certainly a

modern phenomenon. Technological advancements have proven to be a major driving force

behind the growth of the modern gig economy. Rapidly expanding access to high-powered

mobile phones and the explosion of social media users connected workers looking for flexible

job opportunities with consumers that increasingly demanded quick, easy access to services.

84

The gig economy has continued to thrive and is larger than ever; in 2017, the CEO of Intuit, Brad

Smith, stated “The gig economy [in the US] … is now estimated to be about 34% of the

workforce and expected to be 43% by the year 2020”.

85

By 2018, approximately 150 million

12

workers in North America and Western Europe left the mainstream workforce to pursue work as

independent contractors.

86

Are Drivers Employees?

Ride-sharing apps (Uber, Lyft) have been a large part of the growth of the modern gig economy.

As such, they rely heavily on the designation of their workers as independent contractors. The

independent contractor designation is generally viewed as benefiting the employer. It allows

employers to avoid certain expenses that would be associated with full-time employees, such as

social security and Medicare taxes (in the US), overtime and minimum wage payments, and

other traditional employee benefits.

87

A major trend that has potentially widespread implications

for the future of the gig economy, and especially ride-sharing apps, is a push by certain state

lawmakers to force a far more narrow definition of which employment types can be classified as

independent contractors. On September 18, 2019, California became the first state to pass

legislation aimed at limiting the scope of the independent contractor designation.

88

The new

California law, Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5), will take effect in January, 2020 and establishes a test

for organizations that wish to classify their employees as independent contractors. The

requirements include:

1. The worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with

the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and

in fact

2. The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business

3. The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or

business of the same nature as the work performed

89

Self-driving Cars

Self-driving cars are another global phenomenon that will likely have an impact on Uber’s

industry in the future. The concept of a self-driving car traces its roots back as far as the 1920s,

but the first fully autonomous cars weren’t built and ready for testing until the 1980s.

90

However,

progress was minimal until companies like Google began designing and building self-driving

cars around 2009. By 2018, Google’s self-driving car project, Waymo, had logged more than 2

million miles.

91

By 2019, most of the major car companies have made significant investments in

the quickly progressing autonomous vehicle industry. It has been estimated that the autonomous

vehicle industry could be as large as $550 billion by 2026

92

and there could be as many as 20.8

million autonomous vehicles on the road by 2030.

93

INDUSTRY COMPETITION

Expected to reach $300B worldwide by 2030,

94

the ridesharing market is growing globally

thanks to the spread of app-based transportation network services – or ridesharing – as

alternatives to taxis, car ownership, and other traditional means of transportation. Ridesharing is

growing especially fast in developing markets where mobile connectivity is widespread but

individual car ownership is low.

95

In general, users prefer the ease of use and low fares offered

by transportation network companies over traditional cabs and public transit. These companies

13

differentiate their service by maximizing car liquidity, or the quantity of drivers and their

proximity to riders, to keep users engaged with their platforms.

96

Taxis

In the United States, cities maintain regulatory oversight over taxis, although the operation of

taxi businesses falls to individual drivers or private companies. Municipalities issue a limited

number of licenses that permit the operation of a single cab. The restricted supply of licenses has

traditionally made the licenses valuable assets that are often only affordable to wealthy private

investors or large cab companies. Owners of the licenses then lease the right to operate a taxi to a

driver. For example, in New York City licenses are referred to as medallions and are issued by

the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC).

97

The Taxi and Limousine

Commission has restricted the number of taxicabs in operation to approximately 13,500, helping

the valuation of individual medallions reach over $1M as recently as 2014. The Taxi and

Limousine Commission is also responsible for setting predetermined fares and additional charges

for all taxis in the city.

98

The introduction of ridesharing companies that leverage private vehicles and digital dispatch

technology has disrupted the taxi industry. From 2014 to 2018, ride-hailing grew from 8% of all

business traveler ground transportation to 70.5%.

99

The digital coordination of riders with an

uncapped number of drivers has generally led to lower prices and better service outside of

densely populated urban centers.

100

Customers also find the app-based ridesharing platforms to

be more enjoyable, agreeing to fares up front and handling all booking and payment through the

app.

101

In localities across the globe, taxi drivers and cab company owners have organized to lobby

against the proliferation of ridesharing drivers who do not own municipal permits to operate

cabs. Governments, sympathetic to the plight of taxicab drivers, and susceptible to powerful taxi

lobbies, have moved to protect existing taxi companies by prohibiting Uber from operating or

forcing Uber to comply with various rules and regulations.

102

In many cases, these interest

groups assert Uber is operating an illegal taxi-cab service and want Uber regulated accordingly.

This would potentially require Uber to cap its number of drivers and set predetermined fares

instead of using it dynamic market modeling. Uber has often responded aggressively in these

markets, taking to social media or even spurring action by its riders through its app.

103

Lyft

Founded in 2012 and based in San Francisco, Lyft is Uber’s largest competitor in the United

States, with an estimated 27% share of the US ride-hailing market.

104

Its revenue has grown six-

fold since 2016, reaching $2.16B in 2018.

105

Its Q2 2019 revenue was up 62% from the same

quarter the prior year

106

while Uber’s grew 14% during the same period.

107

The ridesharing

company operates in 300 markets in the United States and Canada but has not expanded outside

of North America.

108

As of 2019, Lyft does not offer food delivery, commercial freight, or

fintech services. The company has, however, formed a partnership with Waymo that permitted

Lyft the use of ten autonomous minivans in Phoenix, AZ.

109

14

Although the company is expected to continue its rapid growth, Lyft struggles with profitability.

To grow its supply of drivers, Lyft also uses driver referral bonuses and incentives. These

factors, combined with low ride clearing prices, have kept the start-up unprofitable. Its 2018

revenue of $2.16B was offset with $3.1B in costs, resulting in $911M in losses.

110

In 2018, it

gave 620M rides and had 18.6M active riders, which the company defines as a person taking at

least one ride in a quarter.

111

DiDi

Formed in 2012 by a former Alibaba employee, Cheng Wei, DiDi is a Chinese ridesharing

service valued at $62B. Like Uber, the company offers a variety of services that include

ridesharing, food delivery, and carpooling. Users can also purchase car insurance and personal

loans through the DiDi Finance app.

112

As of 2019, DiDi is reported to have 550 million riders

and over 31 million drivers.

113

In 2016, the company purchased Uber China in a deal valued at $35B. The deal came after

intense competition between DiDi and Uber, who entered the Chinese market only a year prior.

It’s estimated Uber spent about $2B in China in efforts to overcome local regulations and attract

drivers and riders to its platform. Ultimately, Uber merged its Chinese operations with Didi in

exchange for a 17.7% stake in the Chinese company.

114

Due to the fierce competition Uber has faced in some markets, it has made various other deals

like the DiDi deal. In 2017, Uber formed a joint venture with Yandex, a Russian ridesharing

service, whereby it took a 38% stake in the company.

115

Uber spent $2.28B for a 28% stake in

Grab in 2018, a Singapore-based company operating in Southeast Asian markets including

Indonesia and Malaysia.

116

The company now has an estimated valuation of $14B,

117

an 85%

increase since Uber exited. Grab is estimated to have 36 million users and gives 4 million rides a

day.

118

Uber withdrew from each market in a cost cutting effort and to focus on markets with less

competition and friendlier regulations.

Ola

Despite its difficulties in other Asian markets, Uber has not withdrawn from the ridesharing

market in India. It started operations in India three years after its main competitor in India, Ola

Cabs, was founded in Bengaluru, India. With $30.4B in revenue, India is the third largest

ridesharing market behind China and the United States. Due to poor infrastructure, low car

ownership, and low mobile connectivity in areas outside of urban centers, user penetration in the

ridesharing marketplace has been relatively low (12.7%).

119

This is changing rapidly thanks to

expanding mobile networks, increased competition by Uber and Ola, and alternatives to

automobiles. In 2015, Uber invested in an engineering hub in Bangalore citing the availability of

homegrown talent in the tech sector and the opportunity to gain experience in emerging markets

with new technical challenges.

120

Both companies have made large investments in alternative

modes of transportation more suited to the congestion of Indian cities. Ola purchased Vogo, a

scooter rental company, for $100M in 2018.

121

Uber has partnered with Yulu, an e-bicycle

company, and its users can access it through the Uber app.

122

Ola is in 150 Indian cities and plans

to enter another 300 in 2020.

123

In 2017, Ola was reported to have 56% of the Indian ridesharing

market.

124

15

THE FUTURE

Even as Uber grows, it struggles to reach profitability. Legal and regulatory challenges are as

numerous and diverse as the locations in which the company operates and bear significant

implications for Uber’s financial outlook, especially regarding the employment status of drivers.

Internal stakeholders face uncertainty as the company works to rehabilitate a troubled culture and

address issues of diversity and inclusion. The broad environment is rife with direct competition

and the threat of potential competition through technological advances.

16

Exhibit 1. Biographies of Uber Staff Leadership (Abridged from Company Website)

Nelson Chai, Chief Financial Officer

Chai previously served as CEO for the warranty and insurance company, Warranty Group. His

prior experience includes serving as President of CIT Group, Chief Financial Officer of Merrill

Lynch & Co., NYSE Euronext, and Archipelago Holdings. Having earned his B.A. in Economics

at the University of Pennsylvania and an M.B.A. from the Harvard Business School, Chai

currently serves as a board member of the U.S. Fund for UNICEF, the University of

Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences, and Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Tony West, Chief Legal Officer

West oversees legal, compliance, ethics and security functions for Uber. In addition to serving as

the Executive Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs for PepsiCo, West has

also served as Associate Attorney General of the United States and Assistant Attorney General of

the Civil Division of the United States Justice Department during the Obama administration.

Early career experience included serving as an Assistant United States Attorney in California’s

Northern District, Special Assistant Attorney General in California’s Department of Justice, and

as a litigation partner at a private firm. He attended Harvard College for his undergraduate

studies and earned a law degree from Stanford Law.

Nikki Krishnamurthy, Chief People Officer

Krishnamurthy is responsible for human resources, recruiting, workplace, and diversity and

inclusion teams. She held the same role at Expedia prior to joining Uber’s leadership. While at

Expedia, she also headed Expedia Local Expert, a global service focused on travel experiences.

Holding a B.A. in Psychology from Rutgers University, she has also served in human resources

with WaMu and PNC Financial Services Group.

Manik Gupta, Chief Product Officer

Gupta transitioned into this role having previously served as the leader of Uber’s Marketplace

and Maps product teams. Prior experience includes more than seven years at Google Maps,

management of Hewlett-Packard’s e-commerce in Japan and the Asia-Pacific region, and

founding an e-commerce startup that was acquired by a Norwegian firm. Gupta completed

undergraduate studies in computer engineering at Nanyang Technological University and earned

an M.B.A. from the Indian School of Business.

Thuan Pham, Chief Technology Officer

Pham leads Uber’s engineering team. Holding a B.S. in computer science and engineering and an

M.S. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from MIT, Pham has previously served as

Vice President of Engineering for VMware, Westbridge, and DoubleClick.

17

Andrew Macdonald, Senior Vice President, Global Rides & Platform

Macdonald previously served as Uber’s Vice President for the firm’s operations in the Americas

as well as its Global Business Development unit. Prior to joining Uber, he founded two start-ups

after having served as a management consultant focused on technology, finance and

manufacturing for Bain & Company. He serves on the Advisory Council for a university

business incubator in Canada called Ryerson DMZ.

Pierre-Dimitri Gore-Coty, Vice President, International Rides

Gore-Coty oversees Uber’s business in more than 60 countries, having previously served as Vice

President of the ride-hailing business unit in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. He has been

with Uber since its first international foray (France) in 2012. His prior experience included time

at Goldman Sachs, having created a hedge fund while in his mid-20s. Gore-Coty serves as an

Executive Sponsor of the Women of Uber Employee Resource Group.

Jason Droege, Vice President, Uber Everything

Droege was responsible for the first Uber app that extended beyond ride-hailing: Uber Eats.

More generally, he leads the business development unit of the organization that works to

leverage Uber’s existing technology. His prior experience focused on internet-based services and

commerce as well as enterprise software, and he attended the University of California in Los

Angeles.

Rachel Holt, Vice President, New Mobility

Holt leads JUMP, an electric bike share service, and Uber’s business related to scooters, transit,

and hourly rentals. She previously served as Uber’s General Manager for the United States and

Canada. Holt began her time with the company as Uber’s General Manager in Washington, D.C.

Her early career included time with Bain & Company with a focus on private equity, media and

health care, before working in brand management for Clorox. She completed undergraduate

studies at Amherst College and an M.B.A. at Stanford University.

Eric Meyhofer, Head of Advanced Technologies Group

Meyhofer has a background in technology entrepreneurism and education. His start-up ventures

focused on applications of robotics including 3D mapping and high-powered lasers. He is a co-

founder of Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group and served as a Special Faculty member for

more than a decade at Carnegie Mellon University’s Robotics Institute.

Jill Hazelbaker, Senior Vice President, Marketing and Public Affairs

Hazelbaker leads Uber’s worldwide marketing, communications and public policy efforts,

having held a similar role at Snap. Her prior experience includes handling public and

government relations across Europe, as well as public relations in the Middle East and Africa,

having begun her Google career in its Corporate Communications department. Earlier in her

18

career, she led a worked on a number of political campaigns at various levels of government,

most notably including her experience as National Communications Director and Chief

Spokesperson for U.S. Senator John McCain’s presidential campaign in 2008.

Bo Young Lee, Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer

Lee leads Uber’s efforts to create a more diverse and inclusive environment in partnership with a

variety of stakeholders. Her directive is to develop a workplace culture that can empower both

employees and the company as a whole to grow. She previously served in a similar role for two

business units of the Marsh and McLennan Companies. She was a founding consultant for

Aon/Hewitt Associates’ Global Emerging Workforce Solutions and led diversity efforts at Ernst

& Young and National Grid. She has consulted for a number of international organizations, both

for-profit and non-profit, on diversity and inclusion issues. She earned a B.B.A. from the Ross

School of Business at the University of Michigan and an M.B.A. from the Stern School of

Business at New York University.

Source: Uber Newsroom, 2019. Leadership profiles and board of directors.

https://www.uber.com/newsroom/leadership/, Accessed November 20, 2019.

19

Exhibit 2. Uber’s Board of Directors (from company website as of November 4, 2019)

Ronald Sugar, Board Chair

Former Chairperson and CEO of Northrop Grumman

H.E. Yasir Al-Rumayyan

Managing Director of Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund

Ursula Burns

CEO and Chairman of VEON

Garrett Camp

Co-founder of Uber and Founder of Expa

Travis Kalanick

Co-founder and Former CEO of Uber

Dara Khosrowshahi

CEO of Uber

Wan Ling Martello

Executive Vice President of Nestlé

John Thain

Former Chairman and CEO of CIT Group

David Trujillo

Partner at TPG Capital

Source: Uber Newsroom, 2019. Leadership profiles and board of directors.

https://www.uber.com/newsroom/leadership/, Accessed November 20, 2019.

20

Exhibit 3. Uber’s Major Shareholders

Uber’s most significant shareholder prior to IPO:

• Matt Cohler, a venture capitalist on the board of Benchmark Capital, owned in excess of

150 million shares through the firm (11% of Uber).

• Travis Kalanick, Uber’s co-founder and immediate past CEO, owned 117.5 million

shares (8.6% of Uber).

• Garrett Camp, technically Uber’s founder who created the app that Kalanick invested in,

owned 82 million shares (6% of Uber).

• H.E. Yasir Al-Rumayyan is Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund’s managing director,

who, through the fund, owned 73 million shares (5.4% of Uber).

• Ryan Graves, Uber’s first employee who maintained board membership though he had

since ended his employment, owned 33.2 million shares (2.4% of Uber).

• Other board members who own Uber stock include CEO Dara Khosrowshahi with

196,000 shares, Huffington Post founder Ariana Huffington with 22,000 shares, and CIT

Group’s former chairman and CEO John Thain with 130,000 shares.

• Companies with major shareholdings include Google (5% of Uber) and SoftBank

(16.3%).

Source: Klebnikov, S. 2019. Uber could be worth $100 billion after its IPO. Here’s who stands to

make the most money. Money. April 12. http://money.com/money/5641631/uber-ipo-

billionaires/, Accessed November 20, 2019.

21

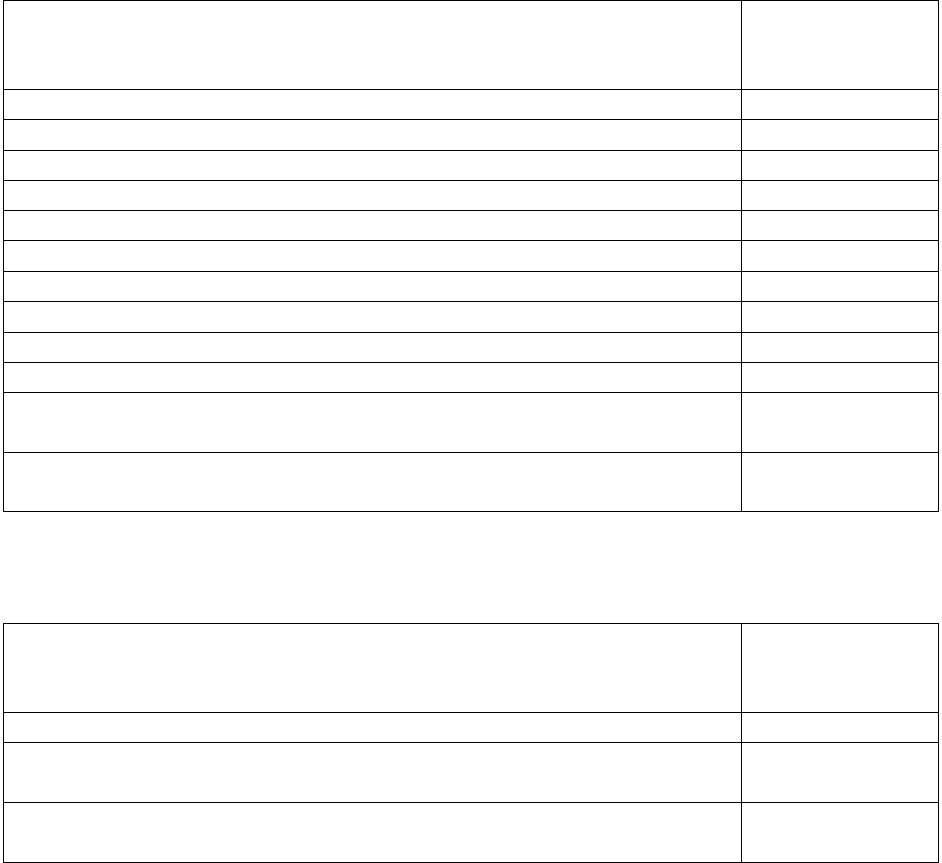

Exhibit 4. Results of Leaked Uber Employee Survey from October 2018

Uber reportedly surveys its employees every six months. Responses to individual survey questions

could be positive, neutral, or negative. According to USA Today and Business Insider, the

following questions garnered a more favorable response in October 2018 than in the previous

administration of the survey:

Statement

Employees

Responding

Positively

I believe that Uber is in a position to succeed over the next two years

83%

I feel heard by my manager

73%

I feel secure about my job

66%

I feel fairly treated

63%

Uber acts in a socially responsible way

63%

I feel the work I’m doing is meaningful and impactful

63%

I have access to the learning and development needed to do my job well

60%

I feel excited to come to work every day

58%

I see myself working at Uber in two years’ time

56%

I am able to manage my work stress in a healthy way

56%

Even if offered a competitive offer or external career opportunity, I

would choose to stay at Uber

45%

I believe my total compensation (base salary, bonuses, benefits, equity)

is fair, relative to similar roles at other companies

40%

Questions with a decreased percentage of favorable responses when compared to the previous

survey reportedly included:

Statement

Employees

Responding

Positively

I am passionate about Uber’s mission

77%

I feel I can report ethical or compliance violations without fear of

retaliation

71%

I have seen positive culture change take place at Uber over the past six

months

62%

Source: Meyer, Z. 2019. Uber employees’ feelings about the company revealed in leaked worker

survey. USA Today. January 1. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/01/01/uber-

employees-leaked-survey/2457260002/, Accessed November 20, 2019.

22

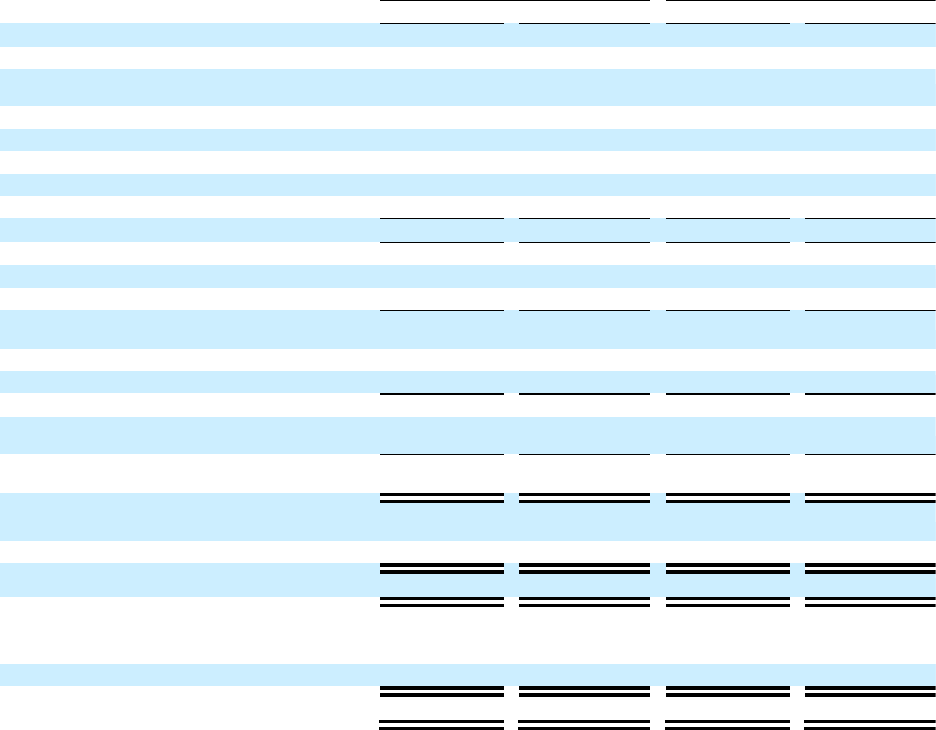

Exhibit 5: Uber’s Consolidated Statements of Operations, Third Quarter 2019

Note: All figures in millions.

Source: Uber Technologies, Inc., 2019. Form 10-Q.

Three Months Ended September 30,

Nine Months Ended September 30,

2018

2019

2018

2019

Revenue

$

2,944

$

3,813

$

8,296

$

10,078

Costs and expenses

Cost of revenue, exclusive of depreciation and

amortization shown separately below

1,510

1,860

4,008

5,281

Operations and support

387

498

1,108

1,796

Sales and marketing

785

1,113

2,177

3,375

Research and development

434

755

1,139

4,228

General and administrative

460

591

1,527

2,652

Depreciation and amortization

131

102

317

371

Total costs and expenses

3,707

4,919

10,276

17,703

Loss from operations

(763

)

(1,106

)

(1,980

)

(7,625

)

Interest expense

(161

)

(90

)

(453

)

(458

)

Other income (expense), net

(54

)

49

4,946

707

Income (loss) before income taxes and loss from

equity method investment

(978

)

(1,147

)

2,513

(7,376

)

Provision for income taxes

1

3

605

20

Loss from equity method investment, net of tax

(15

)

(9

)

(32

)

(25

)

Net income (loss) including non-controlling interests

(994

)

(1,159

)

1,876

(7,421

)

Less: net income (loss) attributable to non-

controlling interests, net of tax

(8

)

3

(8

)

(11

)

Net income (loss) attributable to Uber Technologies,

Inc.

$

(986

)

$

(1,162

)

$

1,884

$

(7,410

)

Net income (loss) per share attributable to Uber

Technologies, Inc. common stockholders:

Basic

$

(2.21

)

$

(0.68

)

$

0.59

$

(6.79

)

Diluted

$

(2.21

)

$

(0.68

)

$

0.52

$

(6.79

)

Weighted-average shares used to compute net

income (loss) per share attributable to common

stockholders:

Basic

445,783

1,700,213

441,301

1,092,241

Diluted

445,783

1,700,213

477,592

1,092,241

23

Exhibit 6: Uber’s Consolidated Balance Sheet, Third Quarter 2019

Note: All figures in millions.

Source: Uber Technologies, Inc., 2019. Form 10-Q.

As of December 31, 2018

As of September 30, 2019

Assets

Cash and cash equivalents

$

6,406

$

12,650

Restricted cash and cash equivalents

67

33

Accounts receivable, net of allowance of $34 and $40, respectively

919

1,154

Prepaid expenses and other current assets

860

1,316

Assets held for sale

406

—

Total current assets

8,658

15,153

Restricted cash and cash equivalents

1,736

1,958

Investments

10,355

10,412

Equity method investments

1,312

1,393

Property and equipment, net

1,641

1,537

Operating lease right-of-use assets

—

1,538

Intangible assets, net

82

74

Goodwill

153

167

Other assets

51

60

Total assets

$

23,988

$

32,292

Liabilities, mezzanine equity and equity (deficit)

Accounts payable

$

150

$

126

Short-term insurance reserves

941

1,023

Operating lease liabilities, current

—

197

Accrued and other current liabilities

3,157

4,026

Liabilities held for sale

11

—

Total current liabilities

4,259

5,372

Long-term insurance reserves

1,996

2,271

Long-term debt, net of current portion

6,869

5,711

Operating lease liabilities, non-current

—

1,459

Other long-term liabilities

4,072

1,428

Total liabilities

17,196

16,241

Commitments and contingencies (Note 15)

Mezzanine equity

Redeemable non-controlling interests

—

309

Redeemable convertible preferred stock, $0.00001 par value, 946,246 and

zero shares authorized, 903,607 and zero shares issued and outstanding,

respectively; aggregate liquidation preference of $14 and $0, respectively

14,177

—

Equity (deficit)

Common stock, $0.00001 par value, 2,696,114 and 5,000,000 shares

authorized, 457,189 and 1,703,630 shares issued and outstanding,

respectively

—

—

Additional paid-in capital

668

30,513

Accumulated other comprehensive loss

(188

)

(185

)

Accumulated deficit

(7,865

)

(15,266

)

Total Uber Technologies, Inc. stockholders' equity (deficit)

(7,385

)

15,062

Non-redeemable non-controlling interests

—

680

Total equity (deficit)

(7,385

)

15,742

Total liabilities, mezzanine equity and equity (deficit)

$

23,988

$

32,292

24

Exhibit 7: Uber’s Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows, Third Quarter 2019

Note: All figures in millions.

Source: Uber Technologies, Inc., 2019. Form 10-Q.

Nine Months Ended September 30,

2018

2019

Cash flows from operating activities

Net income (loss) including non-controlling interests

$

1,876

$

(7,421

)

Adjustments to reconcile net income (loss) to net cash used in operating activities:

Depreciation and amortization

317

371

Bad debt expense

35

79

Stock-based compensation

145

4,353

Gain on extinguishment of convertible notes and settlement of derivatives

—

(444

)

Gain on business divestitures

(3,208

)

—

Deferred income tax

420

(55

)

Revaluation of derivative liabilities

491

(58

)

Accretion of discount on long-term debt

231

80

Payment-in-kind interest

53

10

Loss on disposal of property and equipment

63

14

Impairment on long-lived assets held for sale

122

—

Loss from equity method investment

32

25

Gain on debt and equity securities, net

(1,984

)

(1

)

Non-cash deferred revenue

—

(39

)

Gain on forfeiture of unvested warrants and related share repurchases

(152

)

—

Unrealized foreign currency transactions

54

(16

)

Other

7

18

Change in operating assets and liabilities, net of impact of business acquisitions and disposals:

Accounts receivable

(359

)

(342

)

Prepaid expenses and other assets

(421

)

(467

)

Operating lease right-of-use assets

—

135

Accounts payable

(66

)

(23

)

Accrued insurance reserve

763

356

Accrued expenses and other liabilities

721

997

Operating lease liabilities

—

(94

)

Net cash used in operating activities

(860

)

(2,522

)

Cash flows from investing activities

Proceeds from insurance reimbursement, sale and disposal of property and equipment

329

41

Purchase of property and equipment

(362

)

(406

)

Purchase of equity method investments

(412

)

—

Investments in debt securities

(30

)

—

Proceeds from business disposal, net of cash divested

—

293

Acquisition of businesses, net of cash acquired

(64

)

(7

)

Net cash used in investing activities

(539

)

(79

)

Cash flows from financing activities

Proceeds from issuance of common stock upon initial public offering, net of offering costs

—

7,973

Taxes paid related to net share settlement of equity awards

—

(1,514

)

Proceeds from issuance of common stock related to private placement

—

500

25

ENDNOTES

1

Fowler, G. A. 2015, May 5. There’s an uber for everything now; apps do your chores:

Shopping, parking, cooking, cleaning, packing, shipping and more. Wall Street Journal

(Online). http://newman.richmond.edu:2048/login?url=

https://search-proquest-com.newman.richmond.edu/docview/ 1678612175?accountid=14731.

Accessed November 20, 2019.

2

Uber Technologies, Inc., 2019. Form 10-Q. San Francisco, California: Uber Technologies, Inc.

3

Uber, 2019. A letter from our CEO. https://investor.uber.com/a-letter-from-our-

ceo/?_ga=2.42663077.1819043. Accessed November 20, 2019

328.1572480047-1279676050.1570744267. Accessed November 20, 2019.

4

Isaac, M., & Conger, K. 2019. Uber, Losing $1.8 Billion a Year, Reveals I.P.O. Filing. The

New York Times, April 12: B1.

5

Uber, 2019. Uber’s cultural norms: how we work.

https://s23.q4cdn.com/407969754/files/doc_governance/

Cultural-Norms-Uber.pdf, Accessed November 20, 2019.

6

Isaac, M. 2017. Uber’s new chief unveils a mantra: “We do the right thing. Period.” New York

Times, November 8: B3.

7

O’Kane, S. 2018. Uber changes its logo and redesigns its app. The Verge. September 12.

https://www.theverge. Accessed November 20, 2019.

com/2018/9/12/17851248/uber-new-logo-font-app-design. Accessed November 20, 2019.

8

Uber, 2019. About Uber. https://www.uber.com/us/en/about/, Accessed November 20, 2019.

9

Uber Technologies, Inc., 2019. Form 10-Q. San Francisco, California: Uber Technologies, Inc.

10

Uber, 2019. A letter from our CEO. https://investor.uber.com/a-letter-from-our-

ceo/?_ga=2.42663077.1819043 328.1572480047-1279676050.1570744267, Accessed November

20, 2019.

11

Uber Technologies, Inc., 2019. Form S-1. San Francisco, California: Uber Technologies, Inc.:

12.

12

Uber to Acquire Careem to Expand the Greater Middle East Regional Opportunity Together.

https://www.uber.com/newsroom/uber-careem/. Accessed November 18, 2019.

13

Isaac, M. 2019. Superpumped. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.: 209.

14

Ibid.

15

Ibid.

16

Gerrard, B. 2017. Does the Expedia boss have what it takes to reverse Uber image woes? Dara

Khosroshahi has led a quiet revolution at the travel group, but Uber will pose fresh challenges,

writes Bradley Gerrard. Daily Telegraph. August 29: 31.

17

della Cava, M. 2017. Uber’s pick for CEO is both tough and visionary. USA Today, August

29: 01B.

18

Gerrard, B. 2017. Does the Expedia boss have what it takes to reverse Uber image woes? Dara

Khosroshahi has led a quiet revolution at the travel group, but Uber will pose fresh challenges,

writes Bradley Gerrard. Daily Telegraph. August 29: 31.

19

della Cava, M. 2017. Uber’s pick for CEO is both tough and visionary. USA Today, August

29: 01B.

20

Isaac, M. 2017. Uber board, deeply split, can't agree on a C.E.O. New York Times, July 31:

B1(L).

26

21

Isaac, M. 2017. Uber's new chief unveils a mantra: 'We do the right thing. Period.' New York

Times, November 8: B3(L).

22

Newcomer, E. 2017. Former Uber CEO names two directors without consulting board.

Bloomberg Wire Service. September 30. https://search-proquest-

com.newman.richmond.edu/docview/2010

842504?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14731&selectids=10000008,1006323. Accessed

November 20, 2019.

23

Bensinger, G. Uber board approves series of corporate reforms; board also approves creating

as many as six new seats, three independent, one new chair and two possible for SoftBank. WSJ

Pro. Venture Capital. October 4. https://search-proquest-

com.newman.richmond.edu/docview/1945965765?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14731.

Accessed November 20, 2019.

24

Benner, K. & Isaac, M. 2017. Uber board approves power shift amid strife. New York Times,

October 4: B1(L).

25

Isaac, M. 2019. Superpumped. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.: 194

26

Ibid, 217.

27

Ibid.

28

Ibid, 195.

29

Krisher, T. & Condon, B. 2017. Board adopts report on Uber’s culture, silent on CEO leave.

June 12. http://newman.richmond.edu:2048/login?url=https://search-proquest-

com.newman.richmond.edu/docview/1908584565?accountid=14731. Accessed November 20,

2019.

30

Lashinsky, A. 2017. Wild ride: inside Uber’s quest for world domination. New York:

Portfolio: 161-162.

31

Ibid.

32

Rosenblat, A. 2018. Uberland: How algorithms are rewriting the rules of work. Oakland,

California: University of California Press: 51.

33

Ibid, 50-51.

34

Stone, B. 2017. The upstarts: How Uber, Airbnb and the killer companies of the new Silicon

Valley are changing the world. New York Boston London: Little, Brown and Company: 297.

35

Rosenblat, A. 2018. Uberland: How algorithms are rewriting the rules of work. Oakland,

California: University of California Press: 51.

36

Ibid, 55-59.

37

Ibid, 67.

38

Ibid, 55.

39

Ibid, 54.

40

Rosenblat, A., Levy, K. E. C., Barocas, S., & Hwang, T. 2017. Discriminating tastes: Uber’s

customer ratings as vehicles for workplace discrimination. Policy & Internet, 9(3): 256.

41

Ibid.

42

Rosenblat, A. & Stark, L. 2016. Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: A case study

of Uber’s drivers. International Journal of Communication, 10(2016): 3758.

43

Rosenblat, A. 2018. Uberland: How algorithms are rewriting the rules of work. Oakland,

California: University of California Press: 92

44

Ibid, 150-151.

45

Ibid, 150.

27

46

Malos, S., Lester, G. V., & Virick, M. 2018. Uber drivers and employment status in the gig

economy: Should corporate social responsibility tip the scales? Employee Responsibilities and

Rights Journal, 30(4): 239.

47

Ibid, 239–251.

48

Titcomb, J. 2017. Uber director quits over sexist joke at board meeting. Daily Telegraph, June

15: 3.

49

Holley, P. 2018. Uber’s new CEO aims to turn critics into customers. Washington Post

(Online). April 19. https://go-gale-

com.newman.richmond.edu/ps/i.do?p=UHIC&u=vic_uor&id=GALE|A535317672&v=2.1&it

=r&sid= summon.

50

Campbell, A. 2018. Uber’s HR chief steps down after reportedly ignoring racial discrimination

complaints. Vox. July 11. https://www.vox.com/2018/7/11/17561270/uber-hr-director-liane-

hornsey-resigns-fired.

51

Uber. 2019. Uber D&I report 2019. San Francisco, CA: Uber Technologies Inc.: 3.

52

Ibid, 6.

53

Ibid, 7.

54

Ibid, 3.

55

Ibid, 3.

56

Ibid, 3.

57

Uber, Uber Business Conduct Guide,

https://s23.q4cdn.com/407969754/files/doc_governance/Business-Conduct-Guide-and-Code-of-

Ethics-Uber.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2019.

58

Teixeira, T. S., & Piechota, G. 2019. Unlocking the customer value chain: How decoupling

drives consumer disruption (1 Edition). New York: Currency: 274

59

Holley, P. 2018. Uber’s new CEO aims to turn critics into customers. Washington Post

(Online). April 19. https://go-gale-

com.newman.richmond.edu/ps/i.do?p=UHIC&u=vic_uor&id=GALE|A535317672&v=2.1&it

=r&sid= summon.

60

Malos, S., Lester, G. V., & Virick, M. 2018. Uber drivers and employment status in the gig