Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

For use at 11:00 a.m. EST

February 19, 2021

Monetary Policy rePort

February 19, 2021

Letter of transmittaL

B G

F R S

Washington, D.C., February 19, 2021

T P S

T S H R

The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to

section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act.

Sincerely,

Jerome H. Powell, Chair

Statement on Longer-run goaLS and monetary PoLicy Strategy

Adopted effective January24, 2012; as amended effective January26, 2021

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is rmly committed to fullling its statutory mandate from

the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The

Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity

facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and businesses, reduces economic and nancial

uncertainty, increases the eectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability,

which are essential in a democratic society.

Employment, ination, and long-term interest rates uctuate over time in response to economic and nancial

disturbances. Monetary policy plays an important role in stabilizing the economy in response to these

disturbances. The Committee’s primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy is through changes

in the target range for the federal funds rate. The Committee judges that the level of the federal funds rate

consistent with maximum employment and price stability over the longer run has declined relative to its

historical average. Therefore, the federal funds rate is likely to be constrained by its eective lower bound

more frequently than in the past. Owing in part to the proximity of interest rates to the eective lower bound,

the Committee judges that downward risks to employment and ination have increased. The Committee is

prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.

The maximum level of employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal that is not directly measurable

and changes over time owing largely to nonmonetary factors that aect the structure and dynamics of the

labor market. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to specify a xed goal for employment; rather, the

Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its

maximum level, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The

Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments.

The ination rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee

has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for ination. The Committee rearms its judgment that ination

at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The

Committee judges that longer-term ination expectations that are well anchored at 2 percent foster price

stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhance the Committee’s ability to promote maximum

employment in the face of signicant economic disturbances. In order to anchor longer-term ination

expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve ination that averages 2 percent over time, and

therefore judges that, following periods when ination has been running persistently below 2 percent,

appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve ination moderately above 2 percent for some time.

Monetary policy actions tend to inuence economic activity, employment, and prices with a lag. In setting

monetary policy, the Committee seeks over time to mitigate shortfalls of employment from the Committee’s

assessment of its maximum level and deviations of ination from its longer-run goal. Moreover, sustainably

achieving maximum employment and price stability depends on a stable nancial system. Therefore, the

Committee’s policy decisions reect its longer-run goals, its medium-term outlook, and its assessments

of the balance of risks, including risks to the nancial system that could impede the attainment of the

Committee’s goals.

The Committee’s employment and ination objectives are generally complementary. However, under

circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it takes into account

the employment shortfalls and ination deviations and the potentially dierent time horizons over which

employment and ination are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate.

The Committee intends to review these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its annual

organizational meeting each January, and to undertake roughly every 5 years a thorough public review of its

monetary policy strategy, tools, and communication practices.

Contents

note: This report reects information that was publicly available as of noon EST on February 17, 2021.

Unless otherwise stated, the time series in the gures extend through, for daily data, February16, 2021; for monthly

data, January2021; and, for quarterly data, 2020:Q4. In bar charts, except as noted, the change for a given period is

measured to its nal quarter from the nal quarter of the preceding period.

For gures 15, 33, and 44, note that the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index, the S&P 500 Index, and

the Dow Jones Bank Index are products of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its afliates and have been licensed for

use by the Board. Copyright © 2021 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its afliates. All

rights reserved. Redistribution, reproduction, and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without written

permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more information on any of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices please

visit www.spdji.com. S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, and Dow Jones® is a

registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark

Holdings LLC, their afliates nor their third party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to

the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent, and neither

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates nor their third party licensors shall have

any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

For gure22, neither DTCC Solutions LLC nor any of its afliates shall be responsible for any errors or omissions in any

DTCC data included in this publication, regardless of the cause, and, in no event, shall DTCC or any of its afliates be

liable for any direct, indirect, special, or consequential damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including lost

income or lost prot, trading losses, and opportunity costs) in connection with this publication.

Summary ................................................................ 1

Economic and Financial Developments ......................................... 1

Monetary Policy ........................................................... 2

Special Topics ............................................................. 3

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial Developments ..................... 5

Domestic Developments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Financial Developments .................................................... 26

International Developments ................................................. 32

Part 2: Monetary Policy ................................................. 39

Part 3: Summary of Economic Projections ............................... 49

Abbreviations ...........................................................67

List of Boxes

Monitoring Economic Activity with Nontraditional High-Frequency Indicators ............ 7

Disparities in Job Loss during the Pandemic ..................................... 12

Developments Related to Financial Stability ..................................... 30

The FOMC’s Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy ...... 40

Monetary Policy Rules and Shortfalls from Maximum Employment .................... 45

Forecast Uncertainty ....................................................... 64

1

summary

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to

weigh heavily on economic activity and labor

markets in the United States and around

the world, even as the ongoing vaccination

campaigns oer hope for a return to more

normal conditions later this year. While

unprecedented scal and monetary stimulus

and a relaxation of rigorous social-distancing

restrictions supported a rapid rebound in the

U.S. labor market last summer, the pace of

gains has slowed and employment remains

well below pre-pandemic levels. In addition,

weak aggregate demand and low oil prices

have held down consumer price ination. In

this challenging environment, the Federal

Open Market Committee (FOMC) has held

its policy rate near zero and has continued

to purchase Treasury securities and agency

mortgage-backed securities to support the

economic recovery. These measures, along

with the Committee’s strong guidance on

interest rates and the balance sheet, will ensure

that monetary policy will continue to deliver

powerful support to the economy until the

recovery is complete.

Economic and Financial

Developments

Economic activity and the labor market. The

initial wave of COVID-19 infections led to a

historic contraction in economic activity as

a result of both mandatory restrictions and

voluntary changes in behavior by households

and businesses. The level of gross domestic

product (GDP) fell a cumulative 10percent

over the rst half of 2020, and the measured

unemployment rate spiked to a post–World

War II high of 14.8percent in April. As

mandatory restrictions were subsequently

relaxed and households and rms adapted

to pandemic conditions, many sectors of the

economy recovered rapidly and unemployment

fell back. Momentum slowed substantially

in the late fall and early winter, however, as

spending on many services contracted again

amid a worsening of the pandemic. All told,

GDP is currently estimated to have declined

2.5percent over the four quarters of last

year and payroll employment in January was

almost 10million jobs below pre-pandemic

levels, while the unemployment rate remained

elevated at 6.3percent and the labor force

participation rate was severely depressed.

Job losses have been most severe and

unemployment remains particularly elevated

among Hispanics, African Americans, and

other minority groups as well as those who

hold lower-wage jobs.

Ination. After declining sharply as the

pandemic struck, consumer price ination

rebounded along with economic activity, but

ination remains below pre-COVID levels and

the FOMC’s longer-run objective of 2percent.

The 12-month measure of PCE (personal

consumption expenditures) ination was

1.3percent in December, while the measure

that excludes food and energy items—so-called

core ination, which is typically less volatile

than total ination—was 1.5percent. Both

total and core ination were held down in part

by prices for services adversely aected by

the pandemic, and indicators of longer-run

ination expectations are now at similar levels

to those seen in recent years.

Financial conditions. Financial conditions

have improved notably since the spring of last

year and remain generally accommodative.

Low interest rates, the Federal Reserve’s asset

purchases, the establishment of emergency

lending facilities, and other extraordinary

actions, together with scal policy, continued

to support the ow of credit in the economy

and smooth market functioning. The nominal

Treasury yield curve steepened and equity

prices continued to increase steadily in the

second half of last year as concerns over the

resurgence in COVID-19 cases appeared to

have been outweighed by positive news about

vaccine prospects and expectations of further

2 SUMMARY

scal support. Spreads of yields on corporate

bonds over those on comparable-maturity

Treasury securities narrowed signicantly,

partly because the credit quality of rms

improved and market functioning remained

stable. Mortgage rates for households remain

near historical lows. However, nancing

conditions remain relatively tight for

households with low credit scores and for small

businesses.

Financial stability. While some nancial

vulnerabilities have increased since the start

of the pandemic, the institutions at the core

of the nancial system remain resilient.

Asset valuation pressures have returned to

or exceeded pre-pandemic levels in most

markets, including in equity, corporate bond,

and residential real estate markets. Although

government programs have supported business

and household incomes, some businesses and

households have become more vulnerable to

shocks, as earnings have fallen and borrowing

has risen. Strong capital positions before the

pandemic helped banks absorb large losses

related to the pandemic. Financial institutions,

however, may experience additional losses as

a result of rising defaults in the coming years,

and long-standing vulnerabilities at money

market mutual funds and open-end investment

funds remain unaddressed. Although some

facilities established by the Federal Reserve in

the wake of the pandemic have expired, those

remaining continue to serve as important

backstops against further stress. (See the box

“Developments Related to Financial Stability”

in Part 1.)

International developments. Mirroring the

United States, economic activity abroad

bounced back last summer after the spread

of the virus moderated and restrictions eased.

Subsequent infections and renewed restrictions

have again depressed economic activity,

however. Relative to the spring, the current

slowdown in economic activity has been

less dramatic. Fiscal and monetary policies

continue to be supportive, and people have

adapted to containment measures that have

often been less stringent than earlier.

Despite the resurgence of the pandemic in

many economies, nancial markets abroad

have recovered since the spring, buoyed

by continued strong scal and monetary

policy support and the start of vaccination

campaigns in many countries. With the

abatement of nancial stress, the broad dollar

has depreciated, more than reversing its

appreciation at the onset of the pandemic. On

balance, global equity prices have recovered

and sovereign credit spreads in emerging

market economies and in the European

periphery have narrowed. In major advanced

economies, sovereign yields remained near

historical low levels amid continued monetary

policy accommodation.

Monetary Policy

Review of the strategic framework for monetary

policy. The Federal Reserve concluded the

review of its strategic framework for monetary

policy in the second half of 2020. The review

was motivated by changes in the U.S. economy

that aect monetary policy, including the

global decline in the general level of interest

rates and the reduced sensitivity of ination

to labor market tightness. In August, the

FOMC issued a revised Statement on Longer-

Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy.

1

The revised statement acknowledges the

changes in the economy over recent decades

and articulates how policymakers are taking

these changes into account in conducting

monetary policy. In the revised statement,

the Committee indicates that it aims to attain

its statutory goals by seeking to eliminate

shortfalls from maximum employment—a

broad-based and inclusive goal—and achieve

ination that averages 2percent over time.

Achieving ination that averages 2percent

1. The statement, revised in August2020, was

unanimously rearmed at the FOMC’s January2021

meeting.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 3

over time helps ensure that longer-term

ination expectations remain well anchored at

the FOMC’s longer-run 2percent objective.

Hence, following periods when ination has

been running persistently below 2percent,

appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to

achieve ination moderately above 2percent

for some time. (See the box “The FOMC’s

Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and

Monetary Policy Strategy” in Part 2.)

In addition, in December the FOMC

introduced two changes to the Summary

of Economic Projections (SEP) intended

to enhance the information provided to the

public. First, the release of the full set of SEP

exhibits was accelerated by three weeks, from

the publication of the minutes three weeks

after the end of an FOMC meeting to the

day of the policy decision, the second day of

an FOMC meeting. Second, new charts were

included that display how FOMC participants’

assessments of uncertainties and risks have

evolved over time.

Interest rate policy. In light of the eects of the

continuing public health crisis on the economy

and the associated risks to the outlook, the

FOMC has maintained the target range for the

federal funds rate at 0 to ¼percent since last

March. In pursuing the strategy outlined in its

revised statement, the Committee noted that it

expects it will be appropriate to maintain this

target range until labor market conditions have

reached levels consistent with the Committee’s

assessments of maximum employment and

ination has risen to 2percent and is on track

to moderately exceed 2percent for some time.

Balance sheet policy. With the federal funds

rate near zero, the Federal Reserve has also

continued to undertake asset purchases to

increase its holdings of Treasury securities

by $80billion per month and its holdings

of agency mortgage-backed securities by

$40billion per month. These purchases

help foster smooth market functioning and

accommodative nancial conditions, thereby

supporting the ow of credit to households

and businesses. The Committee expects these

purchases to continue at least at this pace until

substantial further progress has been made

toward its maximum-employment and price-

stability goals.

In assessing the appropriate stance of

monetary policy, the Committee will continue

to monitor the implications of incoming

information for the economic outlook. The

Committee is prepared to adjust the stance of

monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge

that could impede the attainment of the

Committee’s goals.

Special Topics

Disparities in job loss. The COVID-19 crisis

has exacerbated pre-existing disparities in

labor market outcomes across job types and

demographic groups. Job losses last spring

were disproportionately severe among lower-

wage workers, less-educated workers, and

racial and ethnic minorities, as in previous

recessions, but also among women, in contrast

to previous recessions. While all groups

have experienced at least a partial recovery

in employment rates since April2020, the

shortfall in employment remains especially

large for lower-wage workers and for

Hispanics, African Americans, and other

minority groups, and the additional childcare

burdens resulting from school closures have

weighed more heavily on women’s labor

force participation than on men’s labor force

participation. (See the box “Disparities in Job

Loss during the Pandemic” in Part 1.)

High-frequency indicators. The unprecedented

magnitude, speed, and nature of the

COVID-19 shock to the economy rendered

traditional statistics insucient for monitoring

economic activity in a timely manner. As a

result, policymakers turned to nontraditional

high-frequency indicators of activity,

especially for the labor market and consumer

4 SUMMARY

spending. These indicators presented a more

timely and granular picture of the drop and

subsequent rebound in economic activity last

spring. The most recent readings obtained

from those indicators suggest that economic

activity began to edge up again in January,

likely reecting in part the disbursement of

additional stimulus payments to households.

(See the box “Monitoring Economic Activity

with Nontraditional High-Frequency

Indicators” in Part 1.)

Monetary policy rules. Simple monetary policy

rules, which relate a policy interest rate to a

small number of other economic variables,

can provide useful guidance to policymakers.

This discussion presents the policy rate

prescriptions from a number of rules that have

received attention in the research literature,

many of which mechanically prescribe raising

the federal funds rate as employment rises

above estimates of its longer-run level. A rule

that instead responds only to shortfalls of

employment from assessments of its maximum

level is featured to illustrate one aspect of

the FOMC’s revised approach to policy, as

described in the revised Statement on Longer-

Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy. (See

the box “Monetary Policy Rules and Shortfalls

from Maximum Employment” in Part 2.)

5

Domestic Developments

The labor market has partially recovered

from the pandemic-induced collapse,

but the pace of improvement slowed

substantially toward the end of last year . . .

The public health crisis spurred by the

spread of COVID-19 weighed on economic

activity throughout 2020, and patterns

in the labor market reected the ebb and

ow of the virus and the actions taken by

households, businesses, and governments

to combat its spread. During the initial

stage of the pandemic in March and April,

payroll employment plunged by 22million

jobs, while the measured unemployment rate

jumped to 14.8percent—its highest level

since the Great Depression (gures 1 and2).

2

As cases subsided and early lockdowns were

relaxed, payroll employment rebounded

rapidly—particularly outside of the service

sectors—and the unemployment rate fell

back. Beginning late last year, however, the

pace of improvement in the labor market

slowed markedly amid another large wave

of COVID-19 cases. The unemployment

rate declined only 0.4percentage point from

November through January, while payroll

gains averaged just 29,000 per month, weighed

down by a contraction in the leisure and

hospitality sector, which is particularly aected

by social distancing and government-mandated

restrictions.

2. Since the beginning of the pandemic, a substantial

number of people on temporary layo, who should be

counted as unemployed, have instead been recorded as

“employed but on unpaid absence.” The Bureau of Labor

Statistics reports that, if these workers had been correctly

classied, the unemployment rate would have been

5percentage points higher in April. The misclassication

problem has abated since then, and the unemployment

rate in January was at most about ½percentage

point lower than it would have been in the absence of

misclassication.

Part 1

reCent eConomiC and finanCiaL deveLoPments

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Percent

202120192017201520132011200920072005

2. Civilian unemployment rate

Monthly

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

125

130

135

140

145

150

155

Millions of jobs

202120192017201520132011200920072005

1. Nonfarm payroll employment

Monthly

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

6 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Employment-to-

population ratio

50

52

54

56

58

60

62

64

66

68

Percent

202120192017201520132011200920072005

3. Labor force participation rate and

employment-to-population ratio

Monthly

Labor force participation rate

NOTE: The labor force participation rate and the

employment-

to-population ratio are percentages of the population aged 16 and over.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

All told, the incomplete recovery left the level

of employment in January almost 10million

lower than it was a year earlier, while the

unemployment rate stood at 6.3percent—

nearly 3percentage points higher than before

the onset of the pandemic. Most recently,

high-frequency data—including initial claims

for unemployment insurance and weekly

employment data from the payroll processor

ADP—suggest modest further improvement

in the labor market in recent weeks. (For more

discussion of what high-frequency indicators

are suggesting about the current trajectory

of the economy, see the box “Monitoring

Economic Activity with Nontraditional High-

Frequency Indicators.”)

. . . and the harm has been substantial

The damage to the labor market has been

even more substantial than is indicated by

the extent of unemployment alone. The labor

force participation rate (LFPR)—the share

of the population that is either working or

actively looking for work—plunged in March

and April, as many of those who lost their

jobs were not seeking work and so were not

counted among the unemployed. Despite

recovering some over the summer, the LFPR

remains nearly 2percentage points below

its pre-pandemic level (gure3). A number

of factors appear to have contributed to the

continued weakness in the LFPR, including

a lack of job opportunities, the eects of

school closings and virtual learning on

parents’ ability to work, the health concerns

of potential workers, and a spate of early

retirements triggered by the crisis. All told,

the employment-to-population ratio—the

share of the population with jobs, regardless

of the number seeking work—in January

was 3.6percentage points below the level at

the beginning of 2020. Job losses last year

fell most heavily on lower-wage workers

and on Hispanics, African Americans,

and other minority groups. As a result,

the rise in unemployment and the decline

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 7

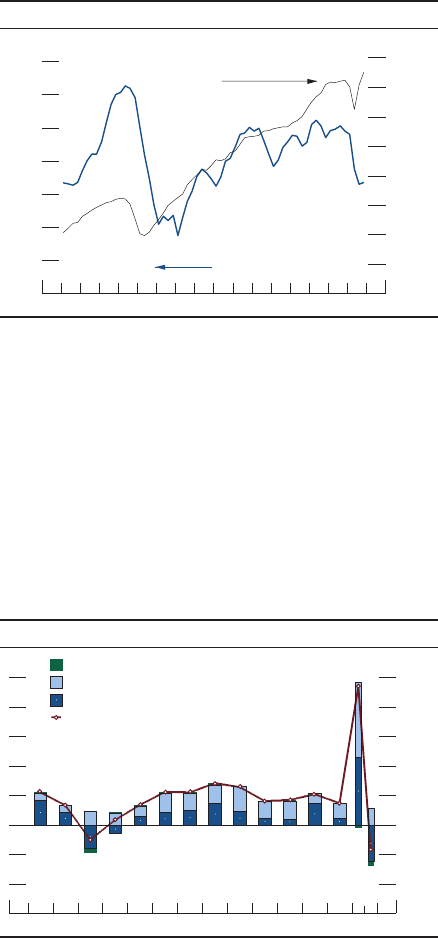

A. Estimates of private payroll employment growth

NOTE: ADP data are weekly and extend through February 6, 2021. BLS data are monthly.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Board sta calculations using ADP, Inc., Payroll Processing Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Current

Employment Statistics (CES).

Payroll employment growth in leisure and hospitality Aggregate payroll employment growth

ADP-FRB, 4-week average

BLS CES

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

Millions of jobs, monthly rate

Feb. Apr. June Aug.Oct. Dec. Feb.

2020 2021

ADP-FRB

ADP-FRB, 4-week average

BLS CES

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Millions of jobs, monthly rate

Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb.

2020 2021

ADP-FRB

state of the labor market.

1

An important example is

data from the payroll processor ADP that cover roughly

20percent of private U.S. employment, a sample size

similar to the one used by the BLS to construct the CES.

Estimates of changes in employment constructed from

ADP data have tracked the of cial CES data remarkably

well since the start of the pandemic recession, and

the ADP data possess the important bene ts of being

available earlier and at a weekly frequency ( gure A,

left panel).

2

1. See, for example, Raj Chetty, John N. Friedman,

Nathaniel Hendren, Michael Stepner, and the Opportunity

Insights Team (2020), “The Economic Impacts of COVID-19:

Evidence from a New Public Database Built Using Private

Sector Data,” NBER Working Paper Series 27431 (Cambridge,

Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, November),

https://www.nber.org/papers/w27431; and Alexander W. Bartik,

Marianne Bertrand, Feng Lin, Jesse Rothstein, and Matt Unrath

(forthcoming), “Measuring the Labor Market at the Onset of

the COVID-19 Crisis,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

2. For further analysis of the ADP employment series, see

Tomaz Cajner, Leland D. Crane, Ryan A. Decker, John Grigsby,

Adrian Hamins-Puertolas, Erik Hurst, Christopher Kurz, and

Ahu Yildirmaz (forthcoming), “The U.S. Labor Market during

the Beginning of the Pandemic Recession,” Brookings Papers

on Economic Activity. Note that the ADP employment series

referenced in this discussion differ from the ADP National

Employment Report, which is published monthly by the ADP

Research Institute in close collaboration with Moody’s Analytics.

The unprecedented magnitude, speed, and nature

of the COVID-19 shock to the economy rendered

traditional statistics insuf cient for monitoring

economic activity in a timely manner. As a result,

policymakers around the world turned to nontraditional

indicators of activity, both those based on private-

sector “big data” and those newly developed by of cial

statistical agencies. Because some of the most salient

characteristics of these indicators are their timeliness

and the time span they cover (such as daily or weekly),

they are often called “high-frequency indicators.”

An important example of the usefulness of high-

frequency indicators is the case of payroll employment.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) monthly measure

of payroll employment is one of the most reliable,

timely, and closely watched business cycle indicators.

However, during the onset of the pandemic in the

United States, even the BLS Current Employment

Statistics (CES) data were published with too long of

a lag to track the dramatic dislocations in the labor

market in a timely manner. Speci cally, from the

second half of March through early April, the economy

was shedding jobs at an unprecedented rate, but

those employment losses were captured only in the

employment situation release issued on May8, 2020.

Because of this lag, economists looked to various

private data sources to gain insights about the current

(continued on next page)

Monitoring Economic Activity with Nontraditional

High-Frequency Indicators

8 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

B. Indicators of consumption growth

Services spending Retail goods spending

Total, Census

30

20

10

+

_

0

10

20

30

Percent change from year earlier

Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb.

2020 2021

Total, NPD

N

OTE

: NPD data are weekly and extend through February 6, 2021,

and Census data are monthly. All series show nominal spending on

nonfood retail goods. Dashed lines represent the rst and second waves

of stimulus tranche.

S

OURCE

: NPD Group; Census Bureau.

Airport passengers

Food services

Hotel occupancy

100

80

60

40

20

+

_

0

20

40

Year-over-year percent change

Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb.

2020 2021

Daily

Health-care visits

N

OTE: Year-over-year percent change in 7-day moving average.

Health-care visits data extend through February 7, 2021; food services

data extend through February 15, 2021; and hotel occupancy data extend

through February 6, 2021.

S

OURCE: SafeGraph, Inc.; Fiserv, Inc.; STR, Inc.; Transportation

Security Administration.

Monitoring Economic Activity (continued)

analytics rm) on nonfood retail sales captured in real

time the dramatic and sudden drop in consumption in

mid-March; the monthly Census Bureau data recorded

that decline only with a lag ( gure B, left panel).

3

The NPD data also re ected how the income support

payments to families, provided by the Coronavirus Aid,

Relief, and Economic Security Act, or CARES Act,

rapidly affected consumer spending in mid-April.

More recently, the NPD data showed some decline

in consumption late last year, followed by a pickup

in January after the passage of the most recent scal

stimulus package. Several nontraditional data sources

illustrate that services spending remains depressed as

social distancing continues to restrain in-person activity

( gure B, right panel).

4

With rapid changes in the economic environment,

many statistical agencies also developed high-frequency

3. Information from the NPD Group, Inc., and its af liates

contained in this report is the proprietary and con dential

property of NPD and was made available for publication

under a limited license from NPD. Such information may not

be republished in any manner, in whole or in part, without the

express written consent of NPD.

4. Services spending accounts for roughly one-half of

aggregate spending, but it is measured with some lag. In

particular, the services spending information folded into

gross domestic product comes from the revenue information

sourced from the Census Bureau’s Quarterly Services Survey

(QSS). The advance QSS (early data for a subset of industries

found in the full QSS) and full QSS are released two and three

months, respectively, after a given quarter ends.

Weekly employment estimates based on ADP data

were particularly valuable not only last spring when

employment plummeted and then quickly rebounded,

but also during the renewed COVID-19 wave that

started this past fall. In particular, high-frequency ADP

employment data indicate that the fall and winter virus

wave had a smaller effect on the labor market than

was seen last spring, likely because there were fewer

mandated shutdowns of businesses than in the spring,

because many businesses implemented adaptations

that made it easier for them to continue to operate

(for example, curbside pickup), and because many

individuals changed their behavior (for example, by

wearing masks such that more economic activities are

deemed safer now than in the spring). Most recently,

the BLS data show that private payroll employment

remained little changed through its survey week in

mid-January, and the ADP data indicate that

employment improved modestly through early

February. Additionally, the latest ADP data indicate

that the leisure and hospitality sector—which includes

hotels, restaurants, and entertainment venues and

is particularly affected by government-mandated

restrictions and social distancing—started adding jobs

again in recent weeks after experiencing a temporary

downturn at the end of last year ( gure A, right panel).

Outside of the labor market, several new high-

frequency indicators have been useful in monitoring

the massive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on

consumer spending. Weekly data from NPD (a market

(continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 9

C. High-frequency indicators by ocial statistical agencies

New business applications Houshold expectations

Cumulative 2020

Cumulative

2021

+

_

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

Thousands

Feb. Apr. June Aug. Oct. Dec.

Weekly

Cumulative

2017-19 average

N

OTE

: The cumulative 2021 data extend through February 6, 2021.

The data are derived from Employer Identication Number applications

with planned wages.

S

OURCE

: Business Formation Statistics, Census Bureau via Haver

Analytics.

High condence

in making

next mortgage

payment

Expect loss of

employment

income in

next 4 weeks

20

30

40

50

60

70

Percent of households

May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan. Feb.

2020 2021

Weekly

High condence

in making

next rent

payment

N

OTE

: Data extend through February 1, 2021. Dashed lines represent

pauses in Household Pulse Survey data collection.

S

OURCE

: Household Pulse Survey, Census Bureau via Haver

Analytics.

nancial struggles of households ( gure C, right

panel). These data indicate that the nancial stress of

households increased late last year as households were

becoming less con dent about being able to make their

next mortgage or rent payment as well as more likely

to expect income loss over the next four weeks, but

households’ nancial expectations improved somewhat

in January.

Overall, nontraditional high-frequency indicators

have served several purposes over the past year.

First, they provide timely alternative estimates that

complement of cial statistics and can also be used to

verify movements in of cial statistics. Second, they are

often helpful for assessing economic developments

more quickly and with greater granularity than what

can be found in of cial statistics. Third, high-frequency

indicators without a direct counterpart in of cial

statistics give a different perspective and help enhance

our understanding of economic developments. These

nontraditional indicators are also subject to several

potential limitations, such as systematic biases due to

nonrepresentativeness of data or small (and possibly

nonrandom) samples. Importantly, only time will tell if

such indicators will continue to provide a signal above

and beyond traditional indicators as the high-frequency

shocks associated with the pandemic dissipate. Overall,

however, the use of nontraditional high-frequency

indicators over the past year has amply shown that they

can yield large bene ts, especially when economic

conditions are changing rapidly.

indicators. For example, the Census Bureau released

data on weekly new business applications ( gure C,

left panel). During the initial stage of the pandemic

recession, new business applications fell compared

with previous years, a typical pattern during economic

downturns. However, new business applications started

to rebound notably during the summer, and for the year

as a whole, they were higher than the average over the

previous three years, a pattern that differs dramatically

from previous business cycles.

5

The increase in

applications appears to be concentrated in industries

that rapidly adapted to the landscape of the pandemic,

such as online retail, personal services, information

technology, and delivery. It remains unclear, however,

whether these business applications will lead to actual

job creation at the same rate as in the past.

6

As another

example, the Census Bureau developed high-frequency

survey statistics that contain information about the

5. For further discussion, see Emin Dinlersoz, Timothy

Dunne, John Haltiwanger, and Veronika Penciakova

(forthcoming), “Business Formation: A Tale of Two Recessions,”

American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings.

6. The link between applications and job creation in the

pre-pandemic period is studied in Kimberly Bayard, Emin

Dinlersoz, Timothy Dunne, John Haltiwanger, Javier Miranda,

and John Stevens (2018), “Early-Stage Business Formation:

An Analysis of Applications for Employer Identi cation

Numbers,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2018-

015 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, March), https://dx.doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2018.015.

10 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

in the employment-to-population ratio

were particularly evident among those

groups (gure4). (For more discussion

of the pandemic’s eects on the labor

market outcomes of various groups, see

the box “Disparities in Job Loss during the

Pandemic.”)

Aggregate wage growth appears to be

little changed despite the weakness in the

labor market

Although weakness in the labor market

generally puts downward pressure on overall

wages, the best available measures suggest

that wage growth in 2020 was little changed

from 2019. Total hourly compensation as

measured by the employment cost index,

which includes both wages and benets, rose

2.6percent during the 12 months ending in

December, only slightly below pre-pandemic

rates (gure5). Wage growth as computed by

the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, which

tracks the median 12-month wage growth

of individuals responding to the Current

Population Survey, was about 3½percent

Average hourly earnings,

private sector

Employment

cost index,

private sector

Atlanta Fed’s

Wage Growth Tracker

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

10

Percent change from year earlier

202120192017201520132011200920072005

5. Measures of change in hourly compensation

Compensation per hour,

business sector

N

OTE: Business-sector compensation is on a 4-quarter percent chang

e

basis.

For the private-sector employment cost index, change is over

the

12

months ending in the last month of each quarter; for p

rivate-sector

average

hourly earnings, the data are 12-month percent changes a

nd

begin

in March 2007; for the Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker,

the

data

are shown as a 3-month moving average of the 12-month

percent

change.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

,

Wage Growth Tracker; all via Haver Analytics.

Hispanic or Latino

Black or African American

Asian

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Percent

202120192017201520132011200920072005

4. Unemployment rate, by race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE:Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. Persons whose ethnicity is identied as Hispanic or L

atino

may be of any race. Small sample sizes preclude reliable estimates for Native Americans and other groups for which monthly data are not reported

by

the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 11

during 2020, similar to the growth rate

in 2019.

3

The continued gains in aggregate

wages mask important heterogeneity,

however; according to the Atlanta Fed data,

workers with lower earnings and nonwhites

experienced larger decelerations in wages than

other groups last year.

Price ination remains low despite

rebounding since last spring

As measured by the 12-month change in

the price index for personal consumption

expenditures (PCE), ination fell from

1.6percent in December2019 to a low of

0.5percent in April, as economic activity

dropped sharply (gure6). Since then,

ination has partially recovered along with the

pickup in demand, but it was only 1.3percent

in December—still well below the Federal

Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) objective

of 2percent. After excluding consumer food

and energy prices, which are often quite

volatile, the 12-month measure of core PCE

ination was 1.5percent in December. An

alternative way to abstract from transitory

inuences on measured ination is provided

by the trimmed mean measure of PCE price

ination constructed by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Dallas.

4

The 12-month change in this

measure declined to 1.7percent in December

3. Some other common wage measures are providing

misleading signals at present because they are dominated

by compositional eects: Pandemic-related job losses fell

most heavily on lower-wage workers, which mechanically

increased measures of average wages. For example,

average hourly earnings from the payroll survey rose

more than 5 percent over the 12 months ending in

January. Similarly, the fourth-quarter reading on

compensation per hour, which includes both wages and

benets, was 7.7percent above its year-ago level. Output

per hour, or productivity, has also been aected by the

same composition eects, rising 2.5percent over the four

quarters of 2020, the fastest pace in a decade.

4. The trimmed mean price index excludes whichever

prices showed the largest increases or decreases in a given

month. Over the past 20years, changes in the trimmed

mean index have averaged ¼percentage point above core

PCE ination and 0.1percentage point above total PCE

ination.

Trimmed mean

Excluding food

and energy

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

12-month percent change

2020201920182017201620152014

6. Change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures

Monthly

Total

NOTE: The data extend through December 2020.

S

OURCE: For trimmed mean, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; for a

ll

else, Bureau of Economic Analysis; all via Haver Analytics.

12 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

distancing measures and relatively few workers are able

to work from home.

2

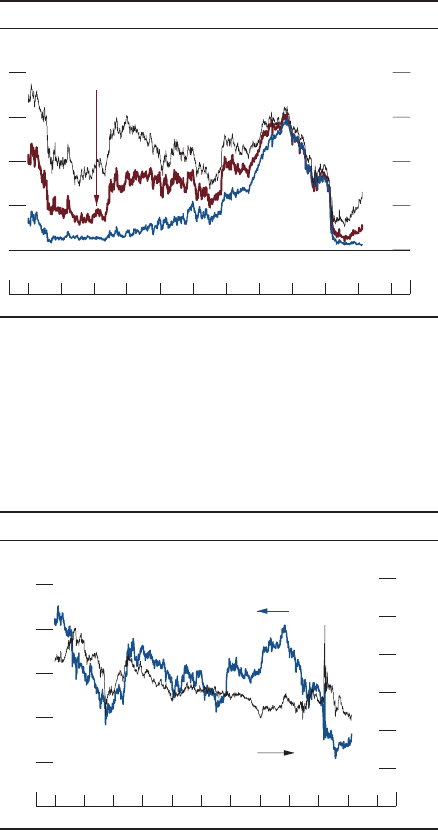

In keeping with the sectoral composition of recent

job losses, workers in lower-wage jobs have been hit

especially hard. Figure B uses data from the payroll

processor ADP to plot employment indexes for four

job tiers de ned by hourly wages. Between February

and April of last year, employment fell most sharply for

jobs in the bottom quartile of the pre-pandemic wage

distribution. Between April and June, employment

rose most quickly for these lowest-paying jobs. In

subsequent months, job gains moderated substantially

for all groups, and as of mid-January, employment in

the lowest-paying jobs was about 20percent below its

2. For instance, in the January2021 round of the Current

Population Survey, 41percent of those employed in the

professional and business services industry reported working

from home during the previous four weeks as a result of the

pandemic, compared with about 7percent of those employed

in leisure and hospitality. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (2021),

“Supplemental Data Measuring the Effects of the Coronavirus

(COVID-19) Pandemic on the Labor Market,” Current

Population Survey, January, https://www.bls.gov/cps/effects-of-

the-coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic.htm.

A. Changes in private-sector employment, by industry

Industry

Percent change since Feb. 2020

(1)

As of Apr. 2020

(2)

As of Jan. 2021

1. Total private ........................... −16.5 −6.6

2. Mining and logging ............... −9.9 −11.7

3. Manufacturing ....................... −10.8 −4.5

4. Construction .......................... −14.6 −3.3

5. Wholesale trade ..................... −6.9 −4.5

6. Retail trade ............................. −15.2 −2.5

7. Transp., warehousing, and

utilities ....................................

−9.1 −2.7

8. Information and nancial

activities ..................................

−4.8 −2.8

9. Professional and business

services ....................................

−11.1 −3.8

10. Education and health

services ....................................

−11.6 −5.4

11. Leisure and hospitality ......... −48.6 −22.9

12. Other services ........................ −23.7 −7.8

N: The data are seasonally adjusted.

S: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Although employment has improved substantially

since its trough in April2020, the labor market

recovery remains far from complete: As of

January2021, the employment-to-population (EPOP)

ratio, a broad measure that encompasses both

increased unemployment and decreased labor force

participation, was still 3.6percentage points below

its February2020 level. All industries, occupations,

and demographic groups experienced signi cant

employment declines at the start of the pandemic,

and, over the ensuing months, all groups have

experienced at least some partial recovery. That

said, employment declines last spring were steeper

for workers with lower earnings and for Hispanics,

African Americans, and other minority groups, and

the hardest-hit groups still have the most ground left

to regain.

Although disparities in labor market outcomes

generally widen during recessions, certain

factors unique to this episode—in particular, the

social-distancing measures taken by households,

businesses, and governments to limit in-person

interactions—have profoundly shaped the incidence

of recent job losses in different segments of the labor

market. Because jobs differ in the degree to which

they involve personal contact and physical proximity,

in whether they can be performed remotely, and in

whether they are deemed to serve “essential” functions,

social-distancing measures have had disparate effects

across industries and occupations. To illustrate this

point, gure A reports net changes in employment in

11 broad industry categories, both during the period

of acute job losses last spring (column 1) and over the

longer interval since the start of the pandemic (column

2). Net job losses through January have been especially

severe in the leisure and hospitality industry—in which

employment is still 22.9percent below pre-pandemic

levels (line 11)—and in other services, a category that

includes barber shops and beauty salons (line 12).

1

By

contrast, employment in most other broad industries is

now 5percent or less below pre-pandemic levels. Job

losses have thus been disproportionately concentrated

in lower-wage consumer service industries, in which

business operations are strongly affected by social-

1. Net job losses have also been pronounced in mining

and logging (line 2), which is unique among these industries

in having experienced further contraction in employment

between April2020 and January2021.

Disparities in Job Loss during the Pandemic

(continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 13

pre-pandemic level. In comparison, employment in the

higher-paying job tiers is now about 10percent or less

below pre-pandemic levels.

Similar disparities are apparent across demographic

groups. Figure C shows the change in each group’s

EPOP ratio. Between February2020 and January2021,

the EPOP ratio fell by a similar amount for both men

and women; in contrast, during many previous

recessions the EPOP ratio declined substantially more

for men. (In fact, given that men’s employment rate was

substantially higher than women’s before the pandemic,

the decline in employment for women as a percentage

of pre-recession employment has been larger, which

contrasts even more starkly with previous recessions.)

Since February2020, the EPOP ratio has fallen more

for people without a bachelor’s degree than for those

with at least a bachelor’s degree, more for prime-age

individuals than for those under age 25 or over age 55,

and more for Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians

than for whites.

3

In general, the groups experiencing the

largest declines in employment since last February are

more commonly employed in the industries that have

3. The decline in employment also appears to have been

relatively large for Native Americans, based on annual average

data for 2020. (Monthly data are not available for this group

because of small sample sizes and are not shown in gure C

for that reason.)

experienced the greatest net employment declines to

date, such as leisure and hospitality; these demographic

groups are also less likely to report being able to work

from home.

4

4. For more information on the groups with the largest

employment declines since February2020, see Kenneth

A. Couch, Robert W. Fairlie, and Huanan Xu (2020),

“Early Evidence of the Impacts of COVID-19 on Minority

Unemployment,” Journal of Public Economics, vol. 192

(December), pp. 1–11; Guido Matias Cortes and Eliza C.

Forsythe (2020), “The Heterogeneous Labor Market Impacts

of the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Upjohn Institute Working Paper

Series 20-327 (Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for

Employment Research, May), https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/

viewcontent.cgi?article=1346&context=up_workingpapers;

and Titan Alon, Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey, and

Michèle Tertilt (2020), “This Time It’s Different: The Role of

Women’s Employment in a Pandemic Recession,” NBER Working

Paper 27660 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic

Research, August), https://www.nber.org/papers/w27660.

Additional details on differences across demographic

groups in the ability to work from home can be found in the

Current Population Survey. For example, in January, around

23percent of white workers reported working from home in the

previous four weeks because of the pandemic, compared with

19percent of African Americans and 14percent of Hispanics;

43percent of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher reported

working from home, compared with 16percent or less for those

with lower levels of education. See Bureau of Labor Statistics,

“Supplemental Data,” in box note 2.

-20 -15 -10 -5 0

C. Change in employment-to-population ratio, by

demographic group

Percentage points

Feb. 2020 to Jan. 2021Feb. to Apr. 2020

Hispanic or Latino

Asian

Black or African American

White

55+

25–54

16–24

Bachelor’s degree and higher

Some college or associate’s degree

High school graduates, no college

Less than a high school diploma

Women

Men

N

OTE: The data are seasonally adjusted. Small sample sizes preclude

reliable estimates for Native Americans and other groups for which

monthly data are not reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

Bottom

Top

Top-middle

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

Week ending February 15, 2020 = 100

Mar. May July Sept. Nov. Jan.

2020 2021

B. Employment declines for low-, middle-, and

high-wage workers

Weekly

Bottom-

middle

N

OTE: The data are seasonally adjusted by the Federal Reserve Board

and extend through January 16, 2021. Wage quartiles are dened using

the February 2020 wage distribution.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Board sta calculations using ADP, Inc.,

payroll processing data.

(continued on next page)

14 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

be important for narrowing the disparities that have

widened since the start of the pandemic, as research

has consistently shown that strong labor markets

especially bene t lower-wage and disadvantaged

workers.

7

The pace of labor market gains will also

depend on how many unemployed workers have

the opportunity to return to their original jobs. In

January2021, 2.2percent of labor force participants

(representing 34.6percent of unemployed workers)

reported being unemployed because of a permanent

job loss, up from 1.3percent of the labor force

(8.8percent of unemployed workers) in April2020.

8

Research has shown that workers who return to their

previous employers after a temporary layoff tend to earn

wages similar to what they were making previously,

whereas laid-off workers who do not return to their

previous employer experience a longer-lasting decline

in earnings.

9

7. For example, see Stephanie R. Aaronson, Mary C. Daly,

William L. Wascher, and David W. Wilcox (2019), “Okun

Revisited: Who Bene ts Most from a Strong Economy?”

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, pp. 333–75,

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/

aaronson_web.pdf; and Tomaz Cajner, Tyler Radler, David

Ratner, and Ivan Vidangos (2017), “Racial Gaps in Labor

Market Outcomes in the Last Four Decades and over

the Business Cycle,” Finance and Economics Discussion

Series 2017-071 (Washington: Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System, June), https://dx.doi.org/10.17016/

FEDS.2017.071.

8. The data are Federal Reserve Board staff calculations

from published Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates. By

comparison, the number of permanent job losers peaked

at 4.4percent of labor force participants (representing

44.8percent of unemployed workers) during the Great Recession.

9. See Louis S. Jacobson, Robert J. LaLonde, and Daniel G.

Sullivan (1993), “Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers,”

American Economic Review, vol. 83 (September), pp. 685–

709; Shigeru Fujita and Giuseppe Moscarini (2017), “Recall

and Unemployment,” American Economic Review, vol. 107

(December), pp. 3875–916; and Marta Lachowska, Alexandre

Mas, and Stephen A. Woodbury (2020), “Sources of Displaced

Workers’ Long-Term Earnings Losses,” American Economic

Review, vol. 110 (October), pp. 3231–66.

Since the start of the pandemic, another important

impediment to individuals’ ability to work or look for

work has been the absence of in-person education for

many K–12 students.

5

Because many working parents

are unable to work from home while monitoring their

children’s virtual education (depending on the nature

of their jobs and the availability of other caregivers),

the widespread lack of K–12 in-person education may

also explain some of the differences across groups.

For example, among mothers aged 25 to 54 with

children aged 6 to 17, the fraction who said they are

not working or looking for work for caregiving reasons

was 2½percentage points higher in the three months

ending January 2021 than over the year-earlier period,

compared with a ½ percentage point increase for

fathers. Relative to white mothers, the increase was

about twice as large for Hispanic mothers and more

than twice as large for African American mothers, and it

was also more than twice as large for mothers without

any college education as for mothers with more

education.

6

As the spread of COVID-19 is contained and

a growing share of the population is immunized,

some of the unique factors that have exacerbated

disparities since the start of the pandemic will likely

ease. For example, as COVID becomes less prevalent,

businesses offering in-person services (for example, in

the leisure and hospitality industry) will move closer

to pre-pandemic levels of employment. In addition, as

more schools return to offering in-person education,

childcare constraints will become less acute.

Even as labor market impediments speci c to the

pandemic subside, however, the speed at which the

labor market moves toward full employment will

5. According to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse

Survey, 85percent of parents surveyed in early January

reported that their children’s classes for the 2020–21 school

year were moved to virtual learning.

6. The ndings are Federal Reserve Board staff estimates

based on publicly available Current Population Survey microdata.

Disparities in Job Loss (continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 15

from 2percent a year earlier, a similar decrease

to those in total and core PCE ination.

The low level of consumer price ination

in 2020 partly reected the deterioration in

economic activity. For example, ination in

tenants’ rent and owners’ equivalent rent,

which tend to be sensitive to overall economic

conditions, softened in 2020 from the rates

observed during the preceding few years.

Low ination also reected the net eect

of a number of pandemic-driven shifts in

specic sectors of the economy, such as a

decline in gasoline prices that resulted from

a collapse in oil prices in the early part of

the year, which only partially reversed in the

second half. Similarly, airfares and hotel prices

fell markedly, driven by huge reductions in

demand due to the pandemic. In contrast,

food prices increased at an unusually fast

pace last year, given stronger demand at retail

grocery stores and, at times, some pandemic-

related supply chain disruptions. In addition,

prices for some durable goods, such as motor

vehicles and home appliances, rose sharply

during the summer and remained somewhat

elevated at the end of the year, in part because

of a pandemic-induced shift in demand away

from services and toward these goods.

Prices of imports and oil have also

rebounded

The partial rebound in ination later in 2020

also stemmed from a rming of import prices.

After declining in the rst half of last year,

nonfuel import prices increased in the second

half, as the dollar depreciated and the recovery

in global demand put upward pressure on

non-oil commodity prices—a substantial

component of nonfuel import prices (gure7).

Prices of both agricultural commodities and

industrial metals increased considerably, and

nonfuel import prices are now higher than

they were a year ago.

Early in the pandemic, benchmark oil prices

fell below $20 per barrel, a level not breached

since 2002. While prices have now nearly

Nonfuel import prices

92

94

96

98

100

102

104

January 2014 = 100

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

20212020201920182017201620152014

7. Nonfuel import prices and industrial metals indexes

January 2014 = 100

Industrial metals

N

OTE: The data for nonfuel import prices are monthly and extend through

December 2020. The data for industrial metals are monthly averages of daily

data and extend through January 29, 2021.

S

OURCE: For nonfuel import prices, Bureau of Labor Statistics; for industrial

metals, S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Spot Index via Haver Analytics.

16 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

recovered, oil consumption and production are

still well below pre-pandemic levels (gure8).

Although global economic activity has picked

up since last spring, oil demand has not fully

recovered, held back by the slow recovery in

travel and commuting. Weak demand has been

met by reductions in supply: U.S. production

has fallen dramatically relative to a year ago,

while OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum

Exporting Countries) and Russia have only

slightly increased production after making

sharp cuts last spring.

Survey-based measures of long-run

ination expectations have been

broadly stable . . .

Despite the volatility in actual ination last

year, survey-based measures of ination

expectations at medium- and longer-term

horizons, which likely inuence actual ination

by aecting wage- and price-setting decisions,

have been little changed on net (gure9).

In the University of Michigan Surveys of

Consumers, the median value for ination

expectations over the next 5 to 10years was

2.7percent in January and early February.

In the Survey of Consumer Expectations,

conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank

of New York, the median of respondents’

expected ination rate three years ahead was

3.0percent in January, somewhat above its

year-earlier level. Finally, in the rst-quarter

Survey of Professional Forecasters, conducted

by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia,

the median expectation for the annual rate

of increase in the PCE price index over the

next 10years was 2.0percent, close to the

level around which it had typically hovered in

previous years.

. . . and market-based measures of

ination compensation have retraced

earlier declines

Ination expectations can also be inferred

from market-based measures of ination

compensation, although the inference is

not straightforward because these measures

are aected by changes in premiums that

provide compensation for bearing ination

Michigan survey,

next 5 to 10 years

NY Fed survey,

3 years ahead

1

2

3

4

Percent

202120192017201520132011200920072005

Survey of Professional

Forecasters,

next 10 years

9. Surveys of ination expectations

NOTE: The series are medians of the survey responses. The Michigan

survey data are monthly and extend through February 2021; the

February data are preliminary. The Survey of Professional Forecasters

data for ination expectations for personal consumption expenditures

are quarterly, begin in 2007:Q1, and extend through 2021:Q1. The N

Y

Fed survey data are monthly and begin in June 2013.

SOURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Federal

Reserve Bank of New York, Survey of Consumer Expectations; Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Survey of Professional Forecasters.

Brent spot price

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Dollars per barrel

2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

8. Spot and futures prices for crude oil

Weekly

24-month-ahead

futures contracts

N

OTE: The data are weekly averages of daily data. The data begin on

Thursdays and extend through February 10, 2021.

S

OURCE

: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 17

and liquidity risks. Measures of longer-term

ination compensation—derived either from

dierences between yields on nominal Treasury

securities and those on comparable-maturity

Treasury Ination-Protected Securities (TIPS),

or from ination swaps—dropped sharply

last March, partly reecting a reduction in

the relative liquidity of TIPS compared with

nominal Treasury securities (gure10). Both

measures rebounded in the next couple of

months as liquidity improved, before drifting

up further through the remainder of 2020 and

early 2021. The TIPS-based measure of 5-to-

10-year-forward ination compensation and

the analogous measure from ination swaps

are now about 2¼ percent and 2½ percent,

respectively, a bit above the average levels seen

in 2019.

5

The plunge and rebound in gross

domestic product reected unusual

patterns of spending during the pandemic

After contracting with unprecedented speed

and severity in the rst half of 2020, gross

domestic product (GDP) rose rapidly in the

third quarter and continued to pick up, albeit

at a much slower pace, in the fourth quarter

(gure11). The rebound in activity reected a

relaxation of voluntary and mandatory social

distancing, as well as unprecedented scal and

monetary support. Nevertheless, the recovery

remains incomplete: At the end of 2020, GDP

was 2.5percent below its level four quarters

earlier. This incomplete recovery reected

weakness in services consumption and overall

exports that resulted largely from ongoing

social-distancing measures to contain the virus,

both at home and abroad. The concentration

of the recession in services is unprecedented in

the United States. Indeed, the sectors that are

typically responsible for the cyclical dynamics

of GDP have shown remarkable resilience:

Activity in the housing market and consumer

spending on goods were both above their

5. As these measures are based on consumer price

index (CPI) ination, one should probably subtract about

¼percentage point—the average dierential between CPI

and PCE ination over the past two decades—to infer

ination compensation on a PCE basis.

Ination swaps

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Percent

20212019201720152013

10. 5-to-10-year-forward ination compensation

Weekly

TIPS breakeven rates

N

OTE

:The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend throug

h

February 12, 2021. TIPS is Treasury Ination-Protected Securities.

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Barclays; Federal R

eserve

Board sta estimates.

Gross domestic product

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Billions of chained 2012 dollars

20202018201620142012201020082006

11. Real gross domestic product and gross

domestic income

Quarterly

Gross domestic income

N

OTE: Gross domestic income extends through 2020:Q3.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

18 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

pre-pandemic levels in the fourth quarter, and

business xed investment and manufacturing

output also recovered rapidly from their

initial plunges.

Consumer spending, particularly on

goods, bounced back in the second half

of 2020 . . .

Household consumption rebounded rapidly

during the late spring and summer from its

COVID-induced plunge, and it continued to

make gains through the fourth quarter, ending

the year 2.6percent below its year-earlier

level. Notably, purchases of both durable

and nondurable goods rose above their pre-

COVID levels in the second half of 2020, as

spending shifted away from services curtailed

by voluntary and mandatory social distancing

(gure12). Within durable goods, sales of light

motor vehicles moved up quickly in the second

half and are now close to their pre-pandemic

level; any residual weakness in sales may be

attributable to low supply, as production

has failed to keep pace with demand.

Services spending also rebounded from the

extraordinarily low level seen in April, but

it remained well below its pre-pandemic

pace through the fourth quarter, as concerns

about the virus continued to limit in-person

interactions. Notably, consumer sentiment has

also remained well below pre-pandemic levels

(gure13).

. . . assisted by government income

support . . .

Consumer spending has been bolstered by

government income support in the form

of unemployment insurance and stimulus

measures targeted at households. These

payments were largest in the spring and

summer of last year, but even in the fourth

quarter aggregate real disposable personal

income (DPI) was 3.7percent above the level

prevailing in late 2019, despite the low level of

employment.

6

The still-elevated level of DPI,

6. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021,

which was enacted in late December, should provide a

Michigan survey

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

1966 = 100

10

30

50

70

90

110

130

150

170

202120182015201220092006

1985 = 100

13. Indexes of consumer sentiment

Conference Board

N

OTE: The data are monthly. Michigan survey data extend through

February 2021; the February data are preliminary.

S

OURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Conference

Board.

Goods

6.5

7.0

7.5

8.0

8.5

9.0

9.5

Billions of chained 2012 dollars

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

202020172014201120082005

12. Real personal consumption expenditures

Billions of chained 2012 dollars

Services

N

OTE: The data are monthly and extend through December 2020.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: FEBRUARY 2021 19

combined with the low level of consumption,

resulted in an aggregate saving rate of more

than 13percent in the fourth quarter, nearly

double its level from a year earlier (gure14).

7

That said, these aggregate gures mask

important variation across households, and

many low-income households, especially

those whose earnings declined as a result of

the pandemic and recession, have seen their

nances stretched.

8

. . . but spending fell back late in the year

As COVID cases began rising again

in November, some states retightened

restrictions, and many households likely cut

back voluntarily on their activities, leading

to a retrenchment in spending on services

such as restaurants and travel. Spending

on durable goods also stepped down late in

the fourth quarter, possibly in part because

many households had already purchased

durable items such as furniture and electronics

earlier in the year. Further, while higher-

income households accrued substantial

savings over the course of 2020, some lower-

income consumers likely began to reduce

their spending toward the end of the year,

as support provided by the Coronavirus

Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act

(CARES Act) waned. More recently,

however, retail sales data and high-frequency

indicators suggest that consumer spending

substantial further boost to DPI in the rst quarter of

this year.

7. The saving rate reached 26percent in the second

quarter of 2020—by far the highest level since World

War II—before falling back as consumption rebounded

and government transfers declined over the course of

the year. Even so, the saving rate in the fourth quarter

remained higher than in any other period since the 1970s.

8. Food pantries saw a signicant increase in demand