Leveraging Asset Management Data for

Improved Water Infrastructure Planning

A NATIONAL REPORT

SPRING 2018

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Page | 2

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PROJECT PARTNERS

PUBLIC SECTOR DIGEST

Public Sector Digest (PSD) is a consulting firm specialized in enterprise asset management and budgeting for local

governments. Their capabilities include research, consulting and software. PSD’s research division produces a

monthly digital and quarterly print publication – the Public Sector Digest – as well as webinars, case studies, grant

applications, and applied research projects.

CANADIAN WATER NETWORK

Canadian Water Network (CWN) is Canada’s trusted broker of research insights for the water sector. When

decision-makers ask, ‘What does the science say about this?’ they frame what is known and unknown in a way

that usefully informs the choices being made.

CANADIAN WATER AND WASTEWATER ASSOCIATION

Canadian Water and Wastewater Association (CWWA) is a non-profit national body representing the common

interests of Canada’s public sector municipal water and wastewater services and their private sector suppliers and

partners.

Page | 3

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 4

NATIONAL CONTEXT ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 7

METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 9

Summary of Survey Results .............................................................................................................................................................. 10

Asset Management Outcomes

.................................................................................................................................................. 11

Asset Management Capacity ..................................................................................................................................................... 12

Asset Management Planning ....................................................................................................................................................... 15

Asset Management Tools ................................................................................................................................................................ 16

Asset Management Data ............................................................................................................................................................... 17

Informed Decision-making ............................................................................................................................................................. 20

Asset Maintenance - Water ........................................................................................................................................................... 21

Asset Maintenance - Wastewater ............................................................................................................................................ 22

Using Data to Support Planned Initiatives ........................................................................................................................... 22

Prioritization of Investments ............................................................................................................................................................ 24

CASE STUDIES

Halifax Water

............................................................................................................................................................................................ 27

City of Guelph ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 38

CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 51

REFERENCES

........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 51

APPENDIX:

Survey: Leveraging Asset Management Data for Improved Water Infrastructure Planning

........... 52

Page | 4

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 2017, Public Sector Digest (PSD), Canadian Water Network (CWN), and the Canadian Water and Wastewater

Association (CWWA) partnered on a national study of municipal asset management practices to identify and

assess what data is being collected by Canadian utilities on water, wastewater, and stormwater assets, and how

this information is being used to inform operations and long-term planning decisions. The study included a

national survey of municipal asset managers and water system managers, as well as in-depth interviews with

utilities that had more advanced asset management programs.

The purpose of the study was to better understand current asset data collection and analysis in Canada for

water, wastewater, and stormwater systems and to identify strategies to improve operations and planning

outcomes.

This study is unique in a Canadian context as it focuses on the capacity side of asset management planning, rather

than technical practices or operational outcomes. At the national level, several studies have measured the state

of municipal infrastructure in Canada — such as the Canadian Infrastructure Report Card — but few have looked

at asset management at the local level. Several municipal associations have measured progress within their own

jurisdictions. For example, PSD partnered with the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) in 2015 to

complete an analysis of 93 municipal asset management plans, which highlighted recent progress in asset

management capacity and identified a need for further work (AMO, 2015). A follow-up study to this earlier

research will be published by AMO later this year.

PSD, CWN, and CWWA’s national survey showed that Canadian municipalities, small and large, are increasingly

employing asset management practices. Smaller municipalities consistently reported fewer dedicated resources

for implementation and also reported that asset data was updated less frequently. Small municipalities were also

more likely (relative to larger municipalities) to indicate lacking a formal asset management plan or indicate that

they were still in the process of developing one. This is not surprising given the lower capacity and resourcing for

asset management in smaller municipalities/utilities.

Despite these capacity differences, both large and small municipalities/utilities rely more heavily on reactive and

time-based asset interventions rather than proactive interventions. Thirty-nine percent of respondents indicated

that more than 50 percent of decisions were reactive, indicating that asset management capacity and resourcing

alone does not guarantee better predictive outcomes. While the higher proportion of reactive maintenance may

more accurately reflect the current state of infrastructure than a municipality/utility’s capacity or maturity of asset

management practices, reactive maintenance ultimately limits a municipality/utility's ability to plan long-term.

When asked what data would be most important to reduce reactive maintenance, inform planned maintenance

activities, and support long-term infrastructure planning, municipalities of all sizes indicated assessed condition

data would be most useful. Despite this, when asked to report on the approximate reliability of captured condition

data for water system assets, 65 percent of respondents indicated that 50 percent or less of their collected data

is objective (i.e., accurate field condition data). The majority of survey respondents reported that subjective

data/analysis (e.g., relying on age-based asset data) comprises a large portion of their asset database and that

accurate (or actual) condition assessments are not routinely collected. Thirty-eight percent of respondents have

Page | 5

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

condition data for more than 75 percent of their vertical assets, but only 28 percent have condition data for more

than 75 percent of linear assets.

Without a sufficient level of confidence in collected asset data, an accurate view of the state of infrastructure and

operations is incomplete, which makes decision-making more challenging. However, it is inefficient and

potentially costly to collect high-quality condition data on every aspect of a water system, especially on

components that provide little ability to predict maintenance needs. Finding the right balance between collecting

high-quality condition data and understanding when other less-intensive means of data collection and analysis

may be sufficient is an important aspect to implementing effective asset management practices.

The results of the national survey indicate good adoption of municipal/utility asset management plans across

Canada, and the application of asset data to inform decisions on performance, cost optimization, and risk

reduction. However, the results have also highlighted a significant shortcoming in the reliability of the data

captured in municipal/utility asset management databases, leading to some uncertainty in how effective this data

is for decision-making. Support and incentives over the last decade from upper-levels of government and others

have focused on the development of asset management plans, which has largely been responsible for the

increased number of asset management plans employed at the local level in Canada. However, as more

municipalities/utilities begin to adopt asset management plans, there is an opportunity to shift support, capacity,

and incentives from plan development to optimizing data collection practices and building capacity to maintain

data collection on an ongoing basis. Focusing on improving the quality and reliability of data will be key to

achieving robust asset management plans. Good quality data will help support decisions and lend confidence to

municipalities/utilities that the right decisions for operations, maintenance, and planning are being made.

EXPERT INSIGHT

“The results of this study are informative and timely as Windsor commences work on their 2018 AMP. Some

of the results will prove helpful for our report to reference experiences of other municipalities similar to ours

and could be leveraged to continue to enhance our asset management plans and practices.”

– Melissa Osborne, Senior Manager Asset Planning, City of Windsor

Vice Chair, Canadian Network of Asset Managers

Page | 6

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

KEY INSIGHTS

• 60 percent of survey respondents indicated that asset inventory data is collected and analyzed to

inform decisions about performance, cost optimization, and risk reduction.

• Municipalities of all sizes indicated that the most important data to inform planned initiatives, reduce

reactive maintenance, and develop long-term infrastructure plans is assessed condition data.

• 65 percent of respondents indicated that 50 percent or less of the data collected is objective data (i.e.,

accurate field condition data).

• Only half of the respondents indicated that they update their asset data at least every six months.

Some municipalities are developing data governance standards to facilitate more regular updates to

asset inventory data.

• The top three approaches reported by respondents for prioritizing asset investments:

Risk-based approach (financial, regulatory and technical risks) – 83% of respondents

Fiscal approach (government taxes and expenditures) – 66% of respondents

Asset lifecycle costing approach – 52% of respondents

• ‘Political priorities’ was listed more frequently among smaller municipalities as an approach used to

prioritize investments.

• 22 percent of respondents, primarily smaller municipalities (<80,000), indicated that a completely

reactive approach is used to prioritize investments.

• Larger municipalities typically have dedicated asset management staff, which allows for more

frequent updates to asset management plans (AMPs) and asset inventory data. The majority of

smaller municipalities (<80,000) surveyed indicated limited staff resources dedicated to asset

management.

Page | 7

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

NATIONAL CONTEXT

With Canada’s mounting infrastructure deficit, increased investment has become a priority for all levels of

government. The federal government has invested billions of dollars in Phase 1 of its $186 billion National

Infrastructure Plan. The rollout of Phase 2 is currently being negotiated with the provinces and territories, and

agreements will be signed by the end of the first quarter of 2018 (Infrastructure Canada, 2018a). Two billion dollars

of federal funds have been allocated to the Clean Water and Wastewater Fund (Infrastructure Canada, 2016),

which targets projects that rehabilitate water treatment and distribution infrastructure and existing wastewater

and stormwater treatment systems, as well as improved asset management, system optimization, and planning

for future upgrades. The federal government also recently established the Canada Infrastructure Bank to support

new infrastructure projects across the country. Provincial and territorial governments have been matching some

of these federal investments and launching their own programs. At the local level, some municipalities have

introduced dedicated tax levies for infrastructure renewal.

The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events are putting added strain on our water-related

infrastructure. Accurate asset condition data is more difficult to ascertain for underground infrastructure than for

above-ground assets, often limiting the quality and quantity of linear asset data available to decision-makers.

However, through innovative and standardized approaches to condition assessments, municipalities can generate

data that will help inform their decisions. Combined with accurate asset replacement costs and risk assessments,

good data empowers municipalities to do the right thing, to the right asset, at the right time, thereby reducing

costs and allowing cities to “size” their infrastructure appropriately. Effective asset management is critical, given

the significant health and safety risks associated with asset failure. Canada’s municipalities need to have a clear

understanding of the value and condition of their assets to prioritize maintenance, upgrades, and new builds

accordingly.

ISO 55000 defines asset management as, “the coordinated activity of an organization to realize value from assets.”

In Canada, asset management came into greater focus at the municipal level in 2009, when the Public Sector

Accounting Board introduced its new accounting standard PSAB 3150, which required municipalities to account

for their tangible capital assets on an annual basis (Public Sector Accounting Group, 2007). Several provinces and

the federal government have since introduced asset management planning requirements to promote maturity in

the sector, and last year the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) launched the Municipal Asset

Management Program (MAMP), a five-year $50 million program funded by the Government of Canada to assist

municipalities in building asset management capacity.

Canada is not alone in its efforts to strengthen asset management practices at the local level. A 2015 study

completed by Hukka and Katko (2015) analyzed current approaches to “resilient asset management and

governance for deteriorating water services infrastructure” across several OECD countries (p.112). The study

found that asset management planning requirements for municipalities were in place in England, Australia, and

Canada. Since this study was published, some U.S. states have also moved ahead with asset management

legislation. Michigan now requires municipalities and utilities to submit asset management plans for drinking

water, wastewater, and stormwater systems by January 1, 2018. Ohio recently enacted Bill 2, which will require

all public drinking water systems in the state to prepare an asset management plan by October 1, 2018.

Page | 8

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

METHODOLOGY

A national survey was sent to municipal water, wastewater, and stormwater utilities across Canada. A leading

advisory committee of experts and practitioners helped to refine the scope of the research, reviewed the survey

results, and contributed to the report’s findings. Interviews were also conducted with municipalities and utilities

with more advanced asset management programs, which are highlighted in two case studies.

Expert Advisory Committee

Darren Row

City Engineer, City of Miramichi

Melissa Osborne

Senior Manager Asset Planning, City of Windsor;

Vice Chair, Canadian Network of Asset Managers

Dr. Klaus Blache

Research Professor, Industrial Systems Engineering

Director of Reliability and Maintainability Centre,

University of Tennessee

John Murray

General Manager of Asset Management, PSD Inc.;

Chair, Canadian Network of Asset Managers

Matthew Dawe

Vice President, PSD Inc.

Dwayne Hodgson

Knowledge Services Advisor, Federation of Canadian

Municipalities

Denny Boskovski

Asset Management and Capital Project Manager,

Town of East Gwillimbury

Jorge Cavalcante

Manager of Engineering and Planning, Region of

Waterloo

Russell Crook

Asset Manager, City of Red Deer

Janelle Price

Senior Manager, Strategic Asset Management,

EPCOR Water Services Inc.

Colwyn Sunderland

Specialist in Asset and Demand Management, Kerr,

Wood and Leidal

Neil Montgomery

Strategic Business Manager for Reliability and

Sustainability, Canadian Bearings Ltd.

Dr. Ming Zuo

Director, International Society of Engineering Asset

Management

Professor, Mechanical Engineering, University of

Alberta

Sydnie Welsh

Policy Analyst, Policy & Results, Strategic and

Horizontal Policy, Infrastructure Canada

The information conveyed in this report does not

necessarily represent the views of the contributors’

employers.

Page | 9

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The survey included 23 questions in three sections: water services, asset management data, and infrastructure

decision-making (see Appendix). The survey was sent to municipalities and utilities across the country in April

2017. The respondents were encouraged to work collaboratively with multiple departments when completing the

survey to capture a complete picture of asset management practices. Fifty-nine municipalities/utilities, who

provide water services to 53 percent of Canada’s population, completed the survey. All ten provinces were

represented, with respondents providing services to populations ranging from 153 to 2.8 million people (see Table

1).

1

This sample provides an informative snapshot of current municipal asset management practices across the

country.

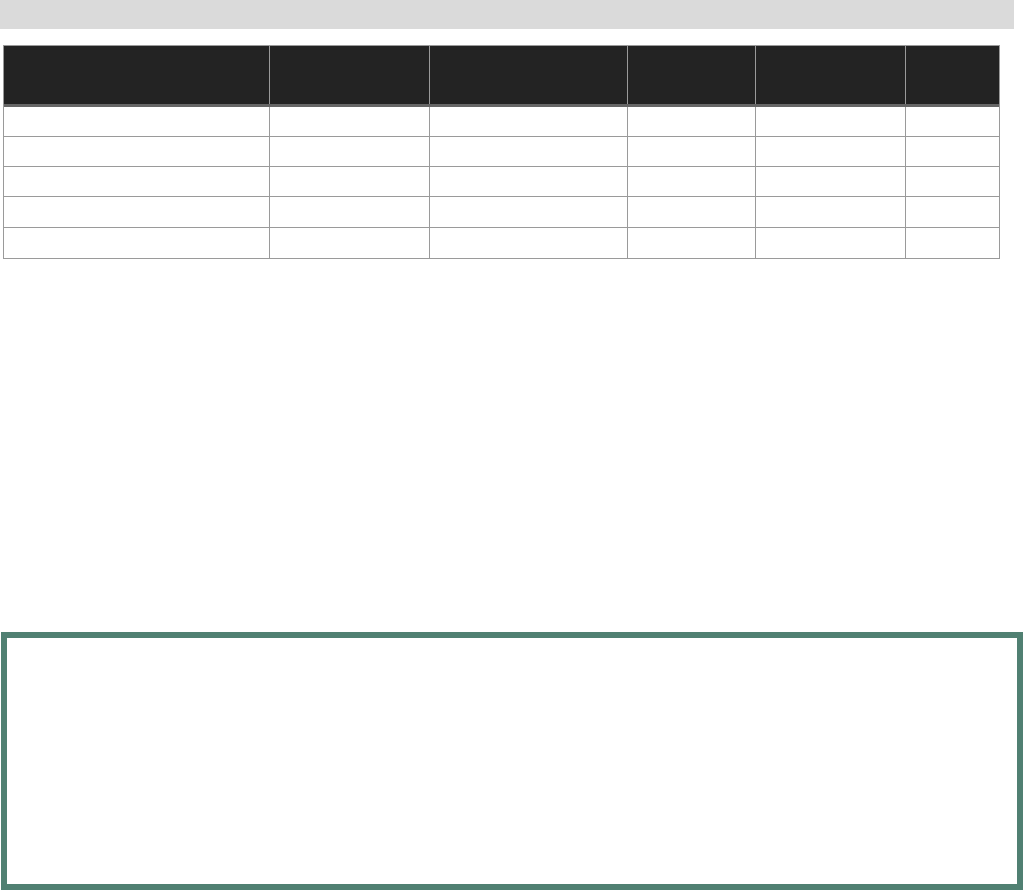

Table 1 Survey Respondents by Province and Population

1

Note: All 59 respondents provided serviced population information, but two respondents did not provide their location, as reflected in the charts above.

Serviced

Population

Range

# of

Respondents

<10,000 15

10,000-

80,000

18

80,000-

500,000

14

500,000+ 12

Province

# of

Respondents

ON 32

AB 7

MB 4

BC 3

SK 3

NL 3

NS 2

PE 1

QC 1

NB 1

Page | 10

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

SUMMARY OF SURVEY RESULTS

• Approximately half of all surveyed municipalities/utilities have a formal asset management plan, but

several more are currently in the process of creating or formalizing a plan.

• Municipalities/utilities of all sizes indicated that assessed condition data is the most important data for

developing long-term infrastructure plans, informing planned maintenance activities and reducing

reactive maintenance.

• Many of the surveyed municipalities/utilities have limited assessed condition data in their asset databases

and rely more heavily on subjective condition data. Larger municipalities collect data using more objective

methods and generally reported greater confidence in data reliability.

• A majority of respondents reported that they have asset replacement cost information as well as

component level asset data in their inventories, which supports more accurate asset management

planning. More than half indicated that they frequently update their asset data (i.e., at least every six

months), which contributes to higher quality asset databases.

• The top three approaches listed by municipalities/utilities for prioritizing asset investments are:

Risk-based considerations (i.e., financial, regulatory, and technical risks) – 83% of respondents

Fiscal considerations (i.e., government taxes and expenditures) – 66% of respondents

Asset lifecycle costing – 52% of respondents

• Twenty-two percent of survey respondents — primarily smaller municipalities with a population under

80,000 — indicated that a completely reactive approach is used to prioritize investments.

• The vast majority of respondents use specialized software to facilitate various asset management

functions. They indicated that they are most satisfied with the data management function of their

software and least satisfied with its analysis and integration capabilities.

• Larger municipalities typically have dedicated asset management staff, which allows for more frequent

updates to asset management plans and asset inventory data. The respondents reported that the majority

of these staff participate in data collection but utilizing the collected data for decision-making and

collaboration is less common.

• Most municipalities/utilities have cross-departmental access to asset databases using GIS or asset

management software, which indicates that the potential for greater corporate-wide collaboration in

asset management planning and decision-making is possible.

Page | 11

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ASSET MANAGEMENT OUTCOMES

Good data is the foundation for asset management programs. There should also be processes in place to support

the continued use of up-to-date data. When asked what outcomes they are achieving using asset data, the

majority of survey respondents (65%) indicated that they are using data to “sustain performance, optimize costs,

and reduce risks” (Figure 1). Most respondents also indicated that they are achieving more than one outcome as

a result of their asset data. Approximately half of the respondents reported achieving other positive outcomes,

including “managing assets to optimize lifecycle” (55%), “optimizing capital investments” (51%), and “developing

strategic long-term goals” for their respective organizations (49%).

When considering population size, municipalities/utilities serving smaller populations indicated multiple positive

outcomes despite the limited capacity for asset management. Of the respondents that service fewer than 80,000

people, the least commonly reported outcome was “developing strategic long-term goals for your organization.”

Without a corporate asset management team, small communities must often rely on existing staff to conduct

asset management work in addition to performing regular duties. An asset management policy helps define roles

and responsibilities, ensuring that longer-term asset management outcomes can be achieved — even in smaller

communities — with support and direction from existing staff. Involving City Council in the development of the

asset management policy and strategy will help build Council buy-in for the asset management program.

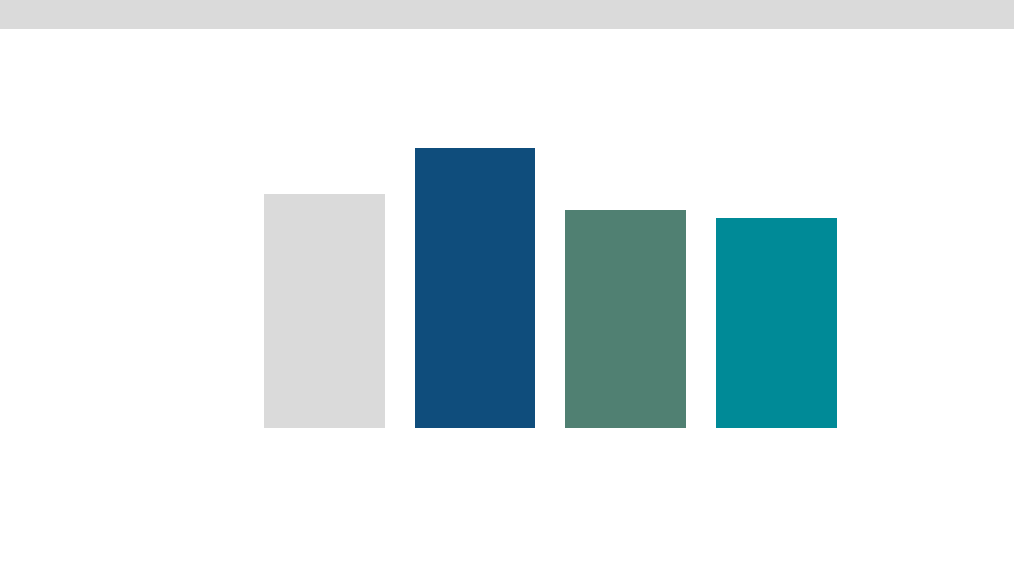

Figure 1 Outcomes Achieved with Asset Data

Managing assets to

optimize asset life cycle

Sustaining performance,

optimizing costs,

reducing risks

51%

49%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

% of respondents

Outcomes

55%

65%

Optimizing capital

investments and

plans for

sustainability

Developing

strategic long

term goals for

organization

Page | 12

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ASSET MANAGEMENT CAPACITY

Without support from grant funding, it may be difficult for some municipalities to implement an AMP and allocate

dedicated resources to corporate asset management (Table 2). Overall, the greatest number of survey

respondents (37%) indicated that they have “limited staff” dedicated to asset management, with an additional 9

percent indicating that they have “adequate staff but no dedicated individual/team.” In most cases, this means

existing staff are spending an insufficient amount of time on asset management as they are responsible for other

duties. However, 32 percent of respondents indicated that they have a “dedicated team” for asset management

and another 15 percent reported having a “dedicated employee.” Just 7 percent of respondents reported having

no staff available for work related to asset management, indicating that despite resource constraints, the majority

of communities are finding ways to assign some resources to asset management programs. Although asset

management does require an upfront investment of time and resources, a properly implemented asset

management program can result in significant cost savings over the long term for local governments and utilities.

Table 2 Asset Management Staffing Capacity

Staffing Capacity

% of

Respondents

No staffing

7

Limited staff

37

Adequate staff but no dedicated

individual/team

9

Part-time employee

0

Dedicated employee

15

Dedicated team

32

EXPERT INSIGHT

“Good asset data is essential to the understanding of level of service provision, often measured through

outcomes achieved, such as the balance between overall performance, risk and cost metrics.”

– John Murray, General Manager of Asset Management, PSD Inc.

Chair, Canadian Network of Asset Managers

Page | 13

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

There is a positive correlation between the population size served by a municipality/utility, and the asset

management staffing capacity within each organization. This is unsurprising given the advantages that larger

municipalities have, such as larger operating budgets and economies of scale. The majority of those who indicated

that they have a dedicated team for asset management have service populations greater than 80,000 people,

whereas the majority of those who indicated that they have limited staffing capacity serve populations of less

than 80,000 people (Table 3). Only those respondents that serve populations of less than 80,000 people indicated

that they currently have no staff working on asset management. Of note is that one respondent that serves less

than 10,000 people reported having a dedicated asset management team in place.

Table 3 Asset Management Staffing Capacity, by Population

Population (000's)

Dedicated

team

Dedicated

employee

Limited

staff

Adequate

staff

No

staff

<10

1

2

11

2

1

10-80

1

4

7

1

3

80-500

6

2

4

2

0

500+

11

1

0

0

0

Total frequency

19

9

22

5

4

Having a dedicated asset management employee or team is likely to improve asset management outcomes for a

community. Regardless of staffing resources, clear priorities and responsibilities can help direct daily activities,

leading to increased efficiency and productivity. When asked about the duties of staff associated with asset

management, the majority of respondents indicated that staff have a combination of key responsibilities (Figure

2). Of those indicating that staff have one primary asset management responsibility, 21 percent pointed to

collecting and managing asset data, while just 2 percent of respondents reported that using asset data for

planning/decision-making is the sole asset management duty of staff.

EXPERT INSIGHT

“In order gain more capacity for asset management data collection, municipalities can work closely with

graduate students and professors with a research focus on engineering asset management. This will enhance

the analysis capabilities of the users while giving graduate students opportunities to practice what they have

learned in research labs. Funding agencies such as NSERC and MITACS can help cover some costs of these

graduate students.”

– Ming Zuo, Professor, University of Alberta

Page | 14

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Of those respondents serving a population greater than 80,000, most answered that their asset management staff

were responsible for collaborating with other divisions and departments (in addition to other asset management

responsibilities). In a larger organization, cross-departmental coordination can promote enterprise-wide buy-in

for the corporate asset management strategy, as well as facilitate the collection and analysis of asset data from

across departments for inclusion in corporate asset management planning. As discussed in the Guelph case study

contained in this report, cross-departmental coordination can also strengthen Council buy-in for asset

management initiatives, presenting a united front and demonstrating the corporate-wide benefits that can be

achieved through asset management.

Figure 2 Key Responsibilities of Asset Management Staff

To facilitate cross-departmental collaboration in asset management, access to asset data is paramount. When

asked which departments have access to their organization’s asset inventory data, almost all survey respondents

indicated that either all their departments have access or that access was mainly provided to finance and public

works/operations. Respondents also indicated that access is primarily facilitated through GIS and asset

management software tools and that the data is accessed to inform asset management plans, operations

activities, and capital planning. It is evident that surveyed municipalities do recognize the importance of cross-

departmental coordination in asset management and have processes in place to support this. What is needed is

better data to be shared across departments.

21%

0%

2%

9%

10%

28%

30%

A) Collect and manage data

B) Assess data

C) Use data for

planning/decision making

D) Collaborate with others for

planning/decision making

E) A and B

F) A, B and C

G) A, B and D

Page | 15

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ASSET MANAGEMENT PLANNING

With renewed Federal Gas Tax Fund agreements requiring municipalities in each provincial/territorial jurisdiction

to meet specific asset management planning deadlines (Infrastructure Canada, 2018b), developing an AMP has

become a key priority for communities across the country. An AMP is a strategic resource for a municipality to

communicate the state of its infrastructure, plan for lifecycle activities over the long term, and ensure that those

activities will be funded. A robust AMP will also incorporate risk analysis and levels of service to help prioritize

community infrastructure projects.

While 51 percent of survey respondents reported having completed an AMP, only 19 percent reported updating

their plan on an annual basis (Table 4). 15 percent indicated that they do not currently have an AMP in place,

while 34 percent responded “other”, indicating that they are in the process of developing or implementing an

AMP. These survey results suggest that at the time of the survey, almost half of the responding municipalities

were not yet implementing a formal asset management plan. Larger municipalities (> 80,000 population) tend to

update their AMPs more frequently and generally have greater capacity to complete regular asset management

activities. Municipalities with fewer than 80,000 people are more likely to lack an AMP, or to be currently working

toward completing their first AMP.

Table 4 Frequency of AMP updates

Frequency of AMP update

% of

Respondents

Every 6 years or more

2

Every 4-5 years

17

Every 2-3 years

13

Annually

19

No AMP

15

Other (first AMP in process)

34

Within some jurisdictions, municipal AMP completion rates are nearing 100 percent as a result of legislative and

funding requirements. According to the Ministry of Infrastructure, 95 percent of Ontario’s municipalities currently

have an AMP in place. The next step for these communities is to ensure that the AMP is informed by accurate data

and built into the municipality’s ongoing asset management program for greater sustainability and improved

decision-making. The frequency with which the AMP is updated will matter less than the quality of the data

captured in the plan and the capacity for the municipality to use the AMP data for decision-making. More

advanced jurisdictions are also requiring that municipal asset management planning be integrated with other

strategic plans and studies. In Ontario, municipalities are required to incorporate proposed new development —

as captured in development charge studies — into their asset management plans to ensure the added long-term

costs to maintain and replace new infrastructure is taken into consideration in capital planning. This helps ensure

that longer term sustainability goals for the community can be achieved.

Page | 16

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ASSET MANAGEMENT TOOLS

Asset management software can assist municipalities and utilities with hosting cross-departmental asset data in

one place and facilitating efficient and frequent updates to asset data. The vast majority of survey respondents

(90%) reported using specialized software to facilitate various asset management functions (Figure 3). 67 percent

of survey respondents indicated that they use software programs for the collection and analysis of tangible capital

asset inventory data, making it the most popular use of asset management software. 53 percent of respondents

reported using software to track asset maintenance work orders and 48 percent reported using software for

infrastructure capital planning and analysis using asset inventory data. Just 10 percent of respondents indicated

that no specialized software programs are used for asset management (i.e., other than Microsoft Excel).

Of the respondents that do not use specialized software, one respondent serves a large population (>500,000),

while the remaining five respondents serve populations less than 80,000. 71 percent of respondents using

software to track asset maintenance work orders service populations greater than 80,000 people.

When asked to describe the effectiveness of the software programs utilized for asset management, respondents

were most satisfied with the data management functions of the software (searches, data sorting, etc.) and the

accessibility of software to multiple users. Respondents were least satisfied with the analysis/reporting

capabilities of software and integration with other management software. This lack of integration may contribute

to the difficulty in translating asset data into strategic planning and decision-making. One respondent commented,

“There are many software packages available that do not seem to be compatible with existing GIS systems used

by the City. Asset management software should be compatible with existing GIS systems to cut down on rework

by City administration.”

Figure 3 Software Used to Facilitate Asset Management

Page | 17

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ASSET MANAGEMENT DATA

Collecting and inventorying asset data is a significant challenge for most communities across the country. Many

municipalities originally implemented asset management practices as an accounting exercise to ensure

compliance with PSAB 3150, but are now interested in adding more meaningful asset data to their inventories and

achieving benefits from their asset management programs. While two survey respondents indicated that they

currently have no asset inventory in place (both communities with populations less than 10,000), 73 percent of

respondents reported having more than 75 percent of their linear assets in an inventory, and 61 percent reported

having more than 75 percent of their vertical assets in an inventory.

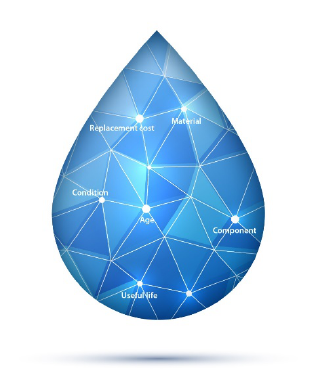

An asset inventory that segments assets into individual components (e.g. segments of a pipe) provides a

municipality with far greater analytical capability, supporting more fine-tuned long-term planning. Figure 4 depicts

the population distribution of survey respondents according to whether they have assets broken down into

components within their inventories. Overall, 78 percent and 61 percent of respondents have asset component

data for their linear and vertical assets, respectively. Only one respondent that serves a population greater than

500,000 reported not having component-level data for assets.

Figure 4 Does your Asset Inventory Include Component Data?

In addition to creating inventories of assets, determining the value of those assets is critical to sound decision-

making. Replacement cost data allows municipalities to calculate the true value of an asset based on what it would

cost to replace it, compared to the more readily available historical cost of the asset (which relies on inflation

calculations to determine present value). The replacement cost of an asset is particularly difficult for small and

rural communities to calculate as they have fewer local price comparisons to draw from. Despite these limitations,

60 percent and 55 percent of respondents reported having replacement costs for linear and vertical assets,

respectively. The survey demonstrated that among the largest municipalities (>500,000 population), the majority

have replacement costs for assets, whereas in smaller communities, municipalities are less likely to have this

information (Figure 5 depicts asset inventory information for both vertical and linear assets).

3

6

2

1

11

11

17

6

0

5

10

15

20

<10 10 - 80 80 - 500 500+

# of respondents

Population (000s)

No Yes

Page | 18

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 5 Does your Asset Inventory Include Replacement Cost Data?

Like replacement cost data, actual asset condition data can be challenging to collect but has a significant impact

on the accuracy of asset management planning. According to the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (2015)

Roads & Bridges Study prepared by Public Sector Digest “evidence indicates that assets with condition ratings are

performing better than their age and expected useful life would suggest” (p.2). The study, which analyzed 93

municipal AMPs across Ontario, found that when field condition data is replaced with only subjective age-based

condition data, the percentage of assets in poor condition increases and the percentage of assets in fair or better

condition decreases for each asset class. Gathering more field condition data can yield a more accurate picture of

the state of a community’s infrastructure and may provide a more realistic outlook.

In this study, few respondents reported having no captured condition data, but a large proportion of respondents

reported having condition data for less than 50 percent of their total assets (Figure 6). In particular, there was a

high proportion of respondents (48%) that had condition data for less than 50 percent of linear assets. Collecting

condition data for underground linear assets is typically more difficult and costly than for water and wastewater

facilities (vertical assets). This is further supported by our survey results, which indicate that 38 percent of

municipalities have captured condition data for more than 75 percent of their vertical assets, while only 28

percent have condition data for more than 75 percent of their linear assets.

5

9

6

1

9

8

7

10

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

<10 10-80 500 500+

# of respondents

Population (000s)

No Yes

EXPERT INSIGHT

“It’s not cost-effective to strive for gap-free asset data registers, or arguably for 100% coverage of CCTV

inspection of gravity sewers, but utilities certainly need enough data to make good decisions and avoid

interventions too early or too late. How much is enough, when you consider that collecting and troubleshooting

data costs lots of money?”

– Colwyn Sunderland, Specialist in Asset and Demand Management, Kerr, Wood and Leidal

80-500

Page | 19

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Programs like FCM’S Municipal Asset Management Program provide funding for municipalities to conduct more

condition assessments to improve asset data quality and accuracy. Condition assessment protocols and data-

gathering tools can also assist municipalities and utilities in the effort to collect, sort, and make use of accurate

condition data more efficiently.

Figure 6 Percentage of Assets with Captured Condition Data, by Asset Type

When asked to report the approximate reliability of captured condition data for water system assets, 65 percent

of respondents indicated that 50 percent or less is objective data (accurate field condition data). As evidenced in

the AMO Roads & Bridges Study referenced above, this lack of quality condition data can result in a significant

over or under estimate of the replacement needs of pipes and other infrastructure. Furthermore, when asked

what information — which is not currently being collected in your asset management data — would be most

helpful to further reduce unplanned (reactive) initiatives, the majority response was “actual condition data” or

“condition assessments”, indicating a potential confidence issue in the data currently contained in municipal asset

databases. The effectiveness of an asset management plan, or any other strategy or process that utilizes asset

inventory data, will largely depend on the quality of the data that is used to populate it.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Less than 50% 51-75% More than

75%

No condition

data

% of respondents

Percentage of assets with condition data

For linear assets (pipes) For vertical assets (facilities)

EXPERT INSIGHTS

“The collection of condition data is a trade-off. As discussed in the Halifax case study included in this report,

more condition data is not always better. There is no need to collect it on assets that aren’t very important, or

for which condition data doesn’t help predict anything.”

– Neil Montgomery, Strategic Business Manager for Reliability and Sustainability,

Canadian Bearings Ltd.

Page | 20

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Data quality is often dependent on the methodology of data collection/verification and how up-to-date the data

is. Approximately half of the respondents (58%) indicated that they frequently update their asset data (i.e., every

six months) and approximately one third (32%) have their asset data collected and verified by a dedicated internal

asset manager (or equivalent). Just 7 percent of respondents reported having an independent third party verify

their asset data. Respondents serving all population sizes reported frequently updating asset information and

using either an internal or external resource to verify asset data (Figure 7). Those respondents that indicated they

did not frequently update or verify asset data suggested that a new process is under development. One

respondent provided the following comment, indicative of a challenge that may be facing many municipalities:

“We struggle with data governance and there are significant delays in asset data updating. We have a Data

Governance Standards project underway to assist with this issue.”

Figure 7 Quality of Organization's Asset Inventory Data, by Population

INFORMED DECISION-MAKING

An asset management team facilitates a sustainable asset management program, which in turn supports good

governance. A good AMP helps focus planned maintenance activities and is an effective communication tool for

city councils and the public. When populated by sound data, properly implemented asset management software

tools can help facilitate regular updates to an AMP and strengthen the analytical capacity of an asset management

team. Ultimately, these tools, strategies, and drivers should inform the decision-making process that occurs at the

departmental and corporate levels regarding municipal assets. When asked what percentage of recent asset

maintenance, repairs, and replacements have been attributed to reactive decision-making, 39 percent of

respondents indicated that more than 50 percent of decisions were reactive. 13 percent of respondents indicated

that more than 50 percent of recent asset interventions were proactive, whereby the organization predicts, plans,

and schedules the asset intervention. Two respondents

9

4

1

6

4

2

7

3

10

7

1

0

4

8

12

16

20

24

28

32

Frequently updated Data collected and verified Independently verified

# of respondents

Attributes of asset data

<10 10-80 80-500 500+

Serviced population ranges (000’s)

Page | 21

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

made 100 percent of recent asset intervention decisions reactively, while one respondent made 75 percent of

recent decisions proactively (the most of any respondent). To a lesser degree, respondents indicated that recent

asset intervention decisions were also attributed to the following decision criteria: time-based, reliability-based

continuous improvement, and precision maintenance.

There was no observed correlation between served population size and the percentage of recent asset

interventions attributed to proactive decision-making. Both large and small municipalities/utilities rely more

heavily on reactive and time-based interventions, with some outliers in all population bands. It is important to

note that the higher proportion of reactive maintenance may not necessarily indicate the maturity of asset

management functions within a municipality. Instead, this may more appropriately reflect a municipality’s current

state of infrastructure. As highlighted in the Canadian Infrastructure Report Card, a large portion of municipal

water, wastewater, and stormwater assets are in fair, poor, and very poor condition, which could be leading to

much of the reactive interventions of a municipality. More reactive interventions may ultimately limit a

municipality's ability to develop longer-term maintenance plans, maintain levels of service, and optimize system

performance.

ASSET MAINTENANCE – WATER

For individual assets, respondents report conducting the most predictive maintenance on their buildings, pumps,

pipes, storage tanks, valves, and hydrants. Conversely, wells and well fields receive the least reactive maintenance

of the listed water assets. For one respondent, 80 percent of their yearly operating costs associated with storage

tanks can be attributed to predictive maintenance. One outlier exists in relation to water meters, with a

respondent indicating that 95 percent of yearly operating costs for water meters can be attributed to predictive

maintenance.

According to the 2011 International Infrastructure Management Manual, predictive maintenance refers to

“condition monitoring activities used to predict failure,” while preventative maintenance refers to “maintenance

that can be initiated without routine or continuous checking (e.g., using information contained in maintenance

manuals or manufacturer recommendations) and is not condition-based” (NAMS & IPWEA, 2011, n.p).

Preventative maintenance on water assets generally consumes a larger portion of annual operating budgets than

predictive maintenance. For seven respondents, more than 50 percent of the operating budget for storage tanks

goes to preventative maintenance. Well fields receive the least preventative maintenance work, with 11

respondents indicating that zero percent of their operating budget goes to preventative maintenance on these

EXPERT INSIGHT

“A goal of asset management is to arrive at the correct maintenance strategy for assets, taking into account

business factors, risk, technology, criticality, and so on. I would even go further and suggest that the whole

field of asset management arose in part as a reaction to maintenance and reliability tactics ignoring the wider

business context.”

– Neil Montgomery, Strategic Business Manager for Reliability and Sustainability,

Canadian Bearings Ltd.

Page | 22

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

assets. Not surprisingly, reactive maintenance receives the largest portion of annual operating budgets for water

assets. For buildings, pipes, and valves, at least 25 percent of respondents have allocated more than 50 percent

of operating budgets to reactive maintenance.

ASSET MAINTENANCE – WASTEWATER

For wastewater assets, respondents reported a similarly limited budget allocation to predictive maintenance

activities. Wastewater lagoons had the highest number of respondents indicating that more than 50 percent of

their operating budget went toward predictive maintenance activities (five respondents). However, that same

asset type also had the highest number of respondents reporting no budget for predictive maintenance (eight

respondents).

Compared to water assets, a higher number of respondents reported more than 50 percent of operating costs

going toward preventative maintenance for wastewater assets. Wastewater pumping stations appear to receive

the most preventative maintenance work, with 29 percent of respondents reporting that 50 percent of operating

costs for pumping stations went toward preventative maintenance.

Finally, manholes and miscellaneous equipment each received more than 50 percent of operating costs for

reactive maintenance for more than 25 percent of respondents.

USING DATA TO SUPPORT PLANNED INITIATIVES

Proper asset management practices should help an organization decrease the percentage of operating costs

attributed to reactive maintenance and increase the percentage of operating costs attributed to planned

initiatives, while decreasing spending overall through the extension of asset useful life. It is important to note that

an asset management program may not always lead to cost savings. Programs may identify that greater

investments in operations or infrastructure may be required to meet the desired levels of service determined by

Council, staff, and the public. Nevertheless, with better data and the capacity to derive insights from that data,

municipalities and utilities can plan and optimize lifecycle activities throughout the year. For water, wastewater,

and stormwater assets and for municipalities of all sizes, the highest number of respondents indicated that age

and condition assessment data were the most important types of asset management data currently used to inform

planned initiatives (Figures 8-10). They also indicated that the number of breaks was important, particularly for

water assets. Among respondents selecting age as a data type used to inform planned initiatives, those

respondents serving a population of fewer than 80,000 people made up the majority for water, wastewater, and

stormwater asset categories.

EXPERT INSIGHT

“Reducing the level of reactive maintenance is the most immediate opportunity for improving many

performance metrics. Doing more predictive maintenance is necessary to find issues and remove the sources

demanding high-level maintenance decisions.”

– Dr. Klaus Blache, Research Professor, Industrial Systems Engineering

Director of Reliability and Maintainability Centre, University of Tennessee

Page | 23

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 8 Types of Data Used to Inform Planned Water Initiatives, by Population

Figure 9 Types of Data Used to Inform Planned Wastewater Initiatives, by Population

2 2 2

1 1 1 1

9

3

2

1

1

3

1

1

4

3 1

1

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Age and/or

number of

breaks

Condtion and/or

criticality

Performance

metrics

Inspection

information

Replacements Historical Cost None/Unknown

# of respondents

Types of asset management data

Serviced population ranges (000's)

<10 10-80 80-500 500+

4

3

1

1

1

1

3 4

2

2 2

1

3

1

2

1

3

1

2 2

1

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Condition

assessments

and/or criticality

Age and/or

number of breaks

CCTV Inspection

information

Asset

management

software

Risk information None/unknown

# of respondents

Types of asset management data

<10 10-80 80-500 500+

Serviced population ranges (000's)

Page | 24

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 10 Types of Data Used to Inform Planned Stormwater Initiatives, by Population

When it comes to utilizing data to minimize reactive initiatives, survey respondents pointed to age and condition

data most frequently. In the case of wastewater initiatives, however, condition was the most frequently reported

dataset. When asked what information would be most helpful in further reducing reactive initiatives, the highest

number of respondents answered condition assessment data (15 respondents each for water and wastewater, 14

for stormwater). For water initiatives, respondents also pointed to risk, pressure information, GIS data, and leak

detection as desired datasets. For wastewater, respondents reported GIS data, replacement costs, and level of

service datasets as valuable additions to further reduce reactive initiatives. Finally, for stormwater assets, soil and

water assessments, material type, and climate change impact datasets were reported as information that would

be helpful in reducing reactive initiatives for respondents.

PRIORITIZATION OF INVESTMENTS

Better asset data, supported by stronger asset management practices, serves to optimize lifecycle activity

planning for an organization and can also facilitate the effective prioritization of asset investments. A key

component of an AMP is the financial strategy, which informs the organization’s long-term approach to financing

its infrastructure needs. This can incorporate data from various sources, such as the Canadian Infrastructure

Report Card, and lifecycle and risk analyses. For communities with mature AMPs, a robust level of service

framework can also inform the financial strategy, taking into consideration the strategic priorities of City Council

and the wider community.

When asked how water system investment decisions are currently being prioritized, most respondents (83%)

reported using a risk-based approach (financial, regulatory, and technical risks). Over half of respondents (66%)

reported using a fiscal approach (government taxes and expenditures; see Figure 11), while approximately half

(52%) reported using an asset lifecycle costing approach to investment prioritization. Nearly a quarter (22%) of

respondents indicated that they are utilizing a completely reactive approach to investment decisions.

1 1

2 2

1

2

2 2

2

3

2

2

3

2

1

3

1

1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Condition

assessments

and/or

criticality

Inspection

information

Age Capacity issues Historical costs CCTV Maintenance

costs

None/unknown

# of respondents

Types of asset management data

<10 10-80 80-500 500+

Serviced population ranges (000's)

Page | 25

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 11 Criteria for Prioritization of Water System Investments, by Population

Large municipalities/utilities (>80,000) favour fiscal, risk, and asset lifecycle costing approaches to make

investment decisions (Figure 12). However, there were three respondents that serve populations of greater than

80,000 people that reported using a completely reactive approach to investments. Among those respondents

serving populations of less than 80,000, risk and fiscal approaches to investment decisions are most widely used,

but political priorities overtake the asset lifecycle costing approach as third most prevalent.

When asked how asset management data is used to support investment decisions, most respondents pointed to

condition and risk rankings (Figure 12). Several respondents also indicated that either no asset management data

is used or it is unknown whether any asset management data is used to support investment decisions. The majority

of the respondents that provided the answer “none/unknown” serve populations of less than 80,000, suggesting

that limited asset management capacity may hinder the ability of organizations to make investment decisions

supported by asset data.

6

2

3

5

11

6

3

12

6

5

9

11

7

5

6

5

4

4

9

6

2

8

4

7

3

9

6

1

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Fiscal approach Smart growth

framework

Triple bottom

line

Political

priorities

Risk (financial,

regulatory,

technical)

Asset life cycle

costing

approach

Completely

reactive

# of respondents

Prioritization criteria

<10 10 - 80 80-500 500+

Serviced population ranges (000’s)

EXPERT INSIGHT

“Twenty-two percent of respondents relying on a reactive approach was a definite surprise. It is evident from

the report that it is crucial to obtain clear and concise data to better enable future planning. Condition data is

an ongoing practice and a plan to review and update conditions should be part of the original plan.”

– Darren Row, City Engineer, City of Miramichi

Asset lifecycle

costing

approach

Page | 26

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 12 How Data is Used to Support Investment, by Population Size

When developing a strategic long-term infrastructure plan, the greatest number of respondents indicated that

the most important data to be considered is “assessed condition” and “actual replacement cost” (Figure 13).

Historical replacement cost was considered to be the least important information when developing a long-term

infrastructure plan, demonstrating the importance of determining actual replacement costs for assets.

Figure 13 The Importance of Data in Developing Long-Term Infrastructure Plans

The results of this study provide a snapshot of the current asset management practices in Canada. While strong

emphasis and support has come from upper levels of government to assist local governments in developing and

implementing asset management plans, it is clear from the survey results that there is still work to be done in data

collection. Municipalities and utilities recognize the importance of having reliable asset data to prioritize

investments and make the right decision, to the right asset, at the right time. As staff resourcing and capacity

increase and new approaches and technologies for data acquisition find more broad scale application, asset

management becomes a very effective and useful tool for prioritization and decision-making. The following case

studies highlight examples of municipal water utilities that have applied effective asset management approaches

and underscore the potential of asset management to support long-term planning.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Historical

replacement cost

Actual

replacement cost

Estimated useful

life

Age-based

condition

Assessed

condition

# of respondents

Type of asset management data

Not important

Somewhat important

Important

Very important

Not applicable

1 1

2

3

4

1

1

2

4

4

2 1

1

1

5

1

2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Capital planning Condition/risk

ranking

Levels of Service Lifecycle/life

expectancy

Risk models Planning/project

prioritization

Projects

prioritized

based on

funding

None/unknown

# of respondents

Types of data

<10 10-80 80-500 500+

Serviced population ranges (000's)

Levels of

service

Page | 27

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CASE STUDY: Halifax Water

The Halifax Regional Water Commission has been responsible for the region’s water system since 1996, and its

wastewater and stormwater systems since 2007. Following the 2007 transfer of wastewater and stormwater

assets from the Halifax Regional Municipality, the utility became responsible for over $4 billion worth of assets,

necessitating better planning and strategic decision-making. Halifax Water built a sustainable asset management

program to assist them in making sound long-term capital and maintenance decisions.

We interviewed the General Manager of Halifax Water, Carl Yates, and Jamie Hannam, Director of Engineering

and Information Systems, to discuss their experience and some of the practices they have found useful with asset

management from the perspective of a utility.

PROGRAM INCEPTION AND PROGRESSION

How did Halifax Water come to be?

In 1996, in what we affectionately refer to as our “shot-gun wedding”, four municipal units were amalgamated to

form the Halifax Regional Municipality. Halifax Water existed before 1996 and after, but it gained additional assets

as part of the overall metro amalgamation. At that time, assets were transferred from Dartmouth and Halifax

County to the Halifax Regional Water Commission. From there we ran a regional water utility up until 2007, and

at that time, the Halifax Regional Municipality transferred the wastewater and stormwater assets to the Halifax

Regional Water Commission.

In 2007, we took on the responsibility of a “one water” utility, with water, wastewater and stormwater services

under one roof, so to speak. We have just completed ten years with that responsibility. In conjunction with the

one water mandate, the utility was rebranded as Halifax Water.

Profile: Carl Yates, General Manager, Halifax Water

Carl is a professional engineer and received his undergraduate degree in civil engineering

from Memorial University in Newfoundland in 1984. He completed a master’s degree in

geotechnical engineering at the Technical University of Nova Scotia, now Dalhousie, in

1992.

Carl began his career with an engineering consulting firm, Jacques Whitford and

Associates, which was subsequently acquired by Stantec. In the fall of 1988, he was hired

by Halifax Water as a Project Engineer. In 1993, he was appointed Chief Engineer of the

Halifax Water Commission. A year later, he was appointed General Manager, and now

oversees the utility’s strategic decision-making.

Page | 28

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

What has your experience been with the evolution of asset management within the utility?

Asset management has certainly ramped up quite a bit in the past few years. We always had an asset management

program, but since 2007 it has taken on a much more significant role in the organization because there is so much

more to keep track of. The other thing to recognize — that is unique to Halifax Water — is that we are regulated.

When I say regulated, I mean more than our provincial environment regulator. I am talking about an economic

regulator, a business regulator: The Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board. From that perspective we are unique in

Canada – we are one of two regulated water, wastewater and stormwater utilities in the country.

“We always had an asset management program, but since 2007 it has taken on a much more

significant role in the organization because there is so much more to keep track of.”

Is there a reason for this regulatory framework?

Yes. It is something I like to call “sound governance.” It was the right approach to ensure that the system got

turned around into a mature, sustainable approach to service. The water utility has been regulated since 1945. As

it continued to evolve and take on greater responsibilities, the Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board continued to

provide oversight. Prior to 2007, water and wastewater were not regulated, and as a result, there needed to be a

whole new framework to establish sustainability.

In conjunction with the 2007 merger, we did a very formal cost of service that may be foreign to many city

departments, but in a regulated environment, it’s like a bible in how you establish your rate structures to ensure

that the utility adheres to cost/causation principles. Those who derive the benefit pay for the service in a fair and

equitable manner and is the key framework for a regulated utility. We conducted the formal cost of service on all

three services, which really highlighted the gaps that were present for each asset category, and we started down

the path of our first integrated resource plan (IRP).

In 2012, we completed our first IRP. The plan is a 30-year framework, which establishes the investments we need

to make in the strategic areas of asset renewal, regulatory compliance and growth – all drivers for infrastructure

needs. We are about to undertake the next iteration of our IRP in 2019, which will benefit from better information.

The key to asset management is getting accurate information.

In 2007, we inherited a significant infrastructure deficit. Services were underfunded and not in compliance with

wastewater and stormwater standards. Our mandate was to bring these services into compliance and put

together a framework to keep them in compliance. In 2007, there were fifteen wastewater plants and only two

were in compliance. Today, we have fourteen plants (we have since decommissioned one) and all but one plant

is in compliance. The plant that is not in compliance will be upgraded this spring.

“The key to asset management is getting accurate information.”

This was one of the key strategic drivers from the merger in 2007. Next year, we will complete another version of

the IRP. With each iteration, there is better information. We inherited both an infrastructure deficit and an

infrastructure information deficit — we didn’t know what we didn’t know. This is how we got started in 1945;

Page | 29

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Halifax Water came about as a result of crises. The water system was devastated after two World Wars and the

Great Depression, which necessitated a sound governance framework and the birth of Halifax Water. In essence,

we are like a Crown Corporation of the municipality, as we are still owned by the Halifax Regional Municipality.

We have our own Board of Directors, but like other municipal utilities (hydro, gas, etc.) we report to the Nova

Scotia Utility and Review Board.

What is your role in asset management and how do you interact with the asset management team?

We operate as a team. The budget process happens with consultation from the whole organization. As leader of

the executive management team, I have the final purview of the capital and operating budgets, and I sign off on

any plans that go to our Board.

We also do a lot of research and are always striving to find innovative approaches and best practices. We work

with researchers at Dalhousie University, which helps guide our long-term investment to improve water policy

and infrastructure. We are also subscribers to the Water Research Foundation – we interface with them to help

make the best investment decisions. Through this approach, I assist with continuing to build up the knowledge

base to support asset management within the organization.

Are there similar asset management regulations for you as a utility as there would be for a municipality? For

example, many municipalities are required to meet certain asset management criteria to be eligible for Federal

Gas Tax Funding.

We don’t get any money from the Federal Gas Tax or the municipal tax system; our revenue base is strictly user

pay. We are eligible to apply for programs like the Clean Water and Wastewater Fund. We have recently taken

full advantage of that, so we do still go after these grants from higher levels of government. We have similar

reporting requirements to Ontario utilities who follow guidelines set out by the Public Sector Accounting Board.

The Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board has an accounting handbook that we must follow, which stipulates how

assets are to be categorized and recorded.

Halifax Water serves over 83,000 customer connections and

employs approximately 470 people. The Halifax Water Board

of Commissioners includes four members of Halifax Regional

Council and three residents who are all appointed by Council

and the Chief Administrative Officer of the Halifax Regional

Municipality.

Page | 30

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

We have full accounting for the depreciation of assets and have always used that as a framework for our capital

funding. We are still working on making our own internal plans more refined, and that comes with better

information. With better information, we can have better asset management plans.

You mentioned how you were like a Crown Corporation of the municipality. Can you give a sense of how you

interact with the municipality?

We certainly work closely with the municipality. Council does not approve our budget or our rates, but we do

bring our business plans to them for information. One of the things we try to take advantage of is an integrated

approach to projects. If the City is going to be doing some work on the street, we want to be there as well.

Hopefully, we will leave the street in good shape for a longer term. We interact with City Councillors on a daily

basis. We are working in their neighbourhoods, so we want to keep them apprised of what we are doing by

treating them as a true shareholder.

RATES, DATA, AND STRATEGIC DECISION-MAKING

Have you seen a focus on levels of service within your utility?

Yes, we are trying to do some calibration on levels of service. However, one of the biggest challenges within asset

management is defining the levels of service. Some areas are easier than others. You can look to benchmarks

nationally and internationally to find something that is meaningful. We have incorporated some aspects into our

balanced corporate scorecard, which we use to measure performance. We know that over time, this will be one

of the focal points of asset management plans — how to link them with a level of service that is appropriate for

those you serve.

Level of service is certainly the new frontier in asset management. Here is an example: You can run a driveway

culvert to failure and that is probably all right, but you cannot run a road cross culvert to failure, because as part

of a public transportation corridor it has greater consequence. You must catch the road cross culvert before it

fails. Nonetheless, as our system matures, we might be able to catch driveway culverts before they fail as well.

With some assets, it makes sense to run them to failure. You look for that sweet spot between reactive and

proactive — where do you get the most for your money? When do you let your watermain fail? You can repair

many watermains in a cost-effective manner, but depending on where that watermain is located, its size and

importance, it can be very disruptive to the community in many ways: social, economic and environmental.

There are considerations outside of strict economics that can prompt you to replace a watermain earlier which is

where it ties to level of service. That level of service is very difficult to get to, because certain watermains will have

a different level of service than others. For example, you can tolerate more failures to a smaller distribution main

than to a transmission main, because a transmission main affects a bigger population and has more impacts. As a

result, you will approach these two differently.

Page | 31

© 2018 PSD, CWN, CWWA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Halifax Water has a stormwater rate in place. Did you see political pushback with the introduction of the rate?

The stormwater charge was a legacy issue from the municipal amalgamation in 1996. Previously, the municipality

charged a combined wastewater and stormwater management fee. With this fee, stormwater was based on water

consumption, and of course, there is no connection between runoff and water consumption. The stormwater

charge was also only levied when customers had a physical water or wastewater pipe connected to their house or

property. Regardless of whether or not there was a piped connection, the Halifax Regional Municipality was

providing stormwater service to all residents, including those who were on wells and septic systems, whose

stormwater system were ditches and culverts in the road right-of-way. These rural residents did not get billed at

all, which meant that they were getting free stormwater service. Revenue from urban and suburban customers

was covering the cost. When you do a cost of service study, what jumps out at you is a clear recognition that the

situation is not fair or equitable. Having one group of customers subsidize services for others is against the Public