The Use, Abuse, and Enforceability

of Non-Compete and No-Poach Agreements:

A Brief Review of the Theory, Evidence, and Recent Reform Efforts

FEBRUARY ISSUE BRIEF

EVAN STARR, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND ROBERT H. SMITH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS

2

Over the last 40 years the startup rate has halved, job mobility has declined 22%,

1

and real wages for the bottom 90% of earners have grown by only 0.4% per year,

with the lowest 10% of earners seeing real wages fall by 5% over this period.

2

Is this

the economy Americans want? What, if anything, can policymakers do to reverse

these trends?

While there are certainly many factors underlying these patterns, two distinct

employment practices have come under increased scrutiny because they curtail

individual freedom to pursue better job opportunities: covenants not to compete

(non-competes) and no-poach agreements.

Non-competes, which in 2014 covered approximately one out of every five labor

force participants in the United States, prohibit individuals from joining or starting

competing businesses, typically within time and geographic boundaries.

3

The use

of non-competes is so pervasive that even volunteers in non-profit organizations, in

states that do not even enforce them,

4

are asked to sign away their post-employment

freedom. No-poach agreements, which are compacts between employers not to hire

workers from each other, have also spread. Estimates suggest they covered nearly

60% of major franchises in the United States in 2016.

5

Given that these constraints prevent individuals from starting companies or taking

better jobs in their chosen field, it is not difficult to see how the expansive use

of these provisions could contribute to the observed declines in U.S. economic

dynamism. To reinforce the suspicion: California, home to some of the most

innovative and highest velocity labor markets in the world, does not generally

enforce non-compete agreements.

6

Yet most other state courts do enforce them,

in large part thanks to a long unresolved debate that juxtaposes the freedom to

contract against bargaining power imbalances and negative externalities. Recent

empirical evidence has brought some clarity to this debate, finding in general

that state policies that curtail the enforceability of non-competes are associated

with greater mobility and entrepreneurship, as well as higher wages. In this brief,

I review these arguments and the burgeoning empirical literature, closing with an

examination of several recent reform efforts.

Non-competes, which in 2014 covered approximately one out of

every five labor force participants in the United States, prohibit

individuals from joining or starting competing businesses.

Why now?

Today, non-competes and no-poach agreements are featured on the agendas

of federal and state legislatures, state Attorneys General (AGs), and antitrust

agencies. Since 2016, two federal agencies have written reports on non-competes,

and state and federal legislatures have proposed more than 20 new laws to reform

non-compete and no-poach agreements.

7

Meanwhile, state AGs have investigated

several high-profile cases of abuse,

8

and the antitrust agencies have also pressed for

reform, beginning with the Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) 2016 Human Resource

Guidelines, which noted that it is illegal for competing firms to agree to limit or fix

the terms of employment.

9

DOJ has continued to prosecute no-poach violations

3

under the Trump Administration,

10

and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

recently signaled its willingness to consider rule-making on non-competes, too.

11

One FTC commissioner, Rohit Chopra, placed labor market competition at the

heart of the agency’s mandate in a recent hearing on Competition and Consumer

Protection in the 21st Century:

12

Open, competitive markets are a foundation of economic liberty. But markets

that suffer from a lack of competition can result in a host of harms. In

uncompetitive markets, firms with market power can raise prices for consumers,

depress wages for workers, and choke off new entrants and other upstarts.

Why are policymakers zeroing in on non-competes and no-poach agreements now?

First, a number of publicized abuses have raised awareness and caused significant

public outcry.

13

In the case of no-poach agreements, media attention prompted

a public backlash so severe that at least eight well-known franchises voluntarily

eliminated them from their organizational contracts.

14

Second, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, policymakers and economists have

become more concerned with declining economic dynamism, wage stagnation,

and the extent of concentration in the labor market.

15

For example, new research

documents that most local labor markets have so few employers hiring in each

job category that they would be considered highly concentrated by the standards

of the DOJ. Such concentration gives firms more “monopsony power” to exert

downward pressure on wages.

16

These trends precipitated the present interest in

non-competes and no-poach agreements for several reasons: First, the theoretical

avenues through which their overuse could contribute to declining dynamism are

clear.

17

Second, there is growing concern that non-competes are too blunt of an

instrument to address legitimate business interests when more scoped alternatives

are available. This point is exacerbated by the fact that non-competes prohibit a

worker from deploying his full range of accumulated knowledge and skills within

the focal industry, even if the present firm only added marginally to those skills

and knowledge. Lastly, since state non-compete law is so varied and momentum for

change is building, there seems to be a real window of opportunity for reform.

Primer on Non-Compete and No-Poach Agreements

What are the differences between non-compete and no-poach agreements?

Non-competes are employment provisions that prohibit individuals from joining

or starting a competitor after they leave their employer, within geographic and

time boundaries. As an example, consider the following non-compete, signed by a

temporarily employed Amazon packer making $13/hr in 2015:

18

During employment and for 18 months after the Separation Date, Employee will

not, directly or indirectly, … engage in or support the development, manufacture,

marketing, or sale of any product or service that competes or is intended to

compete with any product or service sold, offered, or otherwise provided by

Amazon … that Employee worked on or supported, or about which Employee

obtained or received Confidential Information.

4

While Amazon’s reach into so many corners of the American market makes these

broad restrictions particularly onerous, the agreement itself is representative of a

typical non-compete many workers sign as a condition of employment today.

No-poach agreements, on the other hand, are generally organization-level

agreements not to recruit workers from each other. Here is an example of a no-poach

agreement between franchisees at McDonald’s:

19

During the term of this Franchise, Franchisee shall not employ or seek to employ

any person who is at the time employed by McDonald's, any of its subsidiaries, or

by any person who is at the time operating a McDonald's restaurant or otherwise

induce, directly or indirectly, such person to leave such employment. This

paragraph 14 shall not be violated if such person has left the employ of any of

the foregoing parties for a period in excess of six (6) months.

How common are non-competes and no-poach agreements?

It is difficult to know exactly how common no-poach agreements are because they

are often forged in secret and, due to their collusive nature, they are generally illegal.

An exception is the franchise sector, which currently occupies a legal gray area that

the courts are sorting out.

20

Data from that sector shows that approximately 58%

of major franchises in the United States used no-poach agreements among their

franchisees in 2016, up from 36% in 1996.

21

Moreover, several recent Department of

Justice investigations have uncovered the illegal use of no-poach agreements among

Silicon Valley tech giants as well as among railroad suppliers.

22

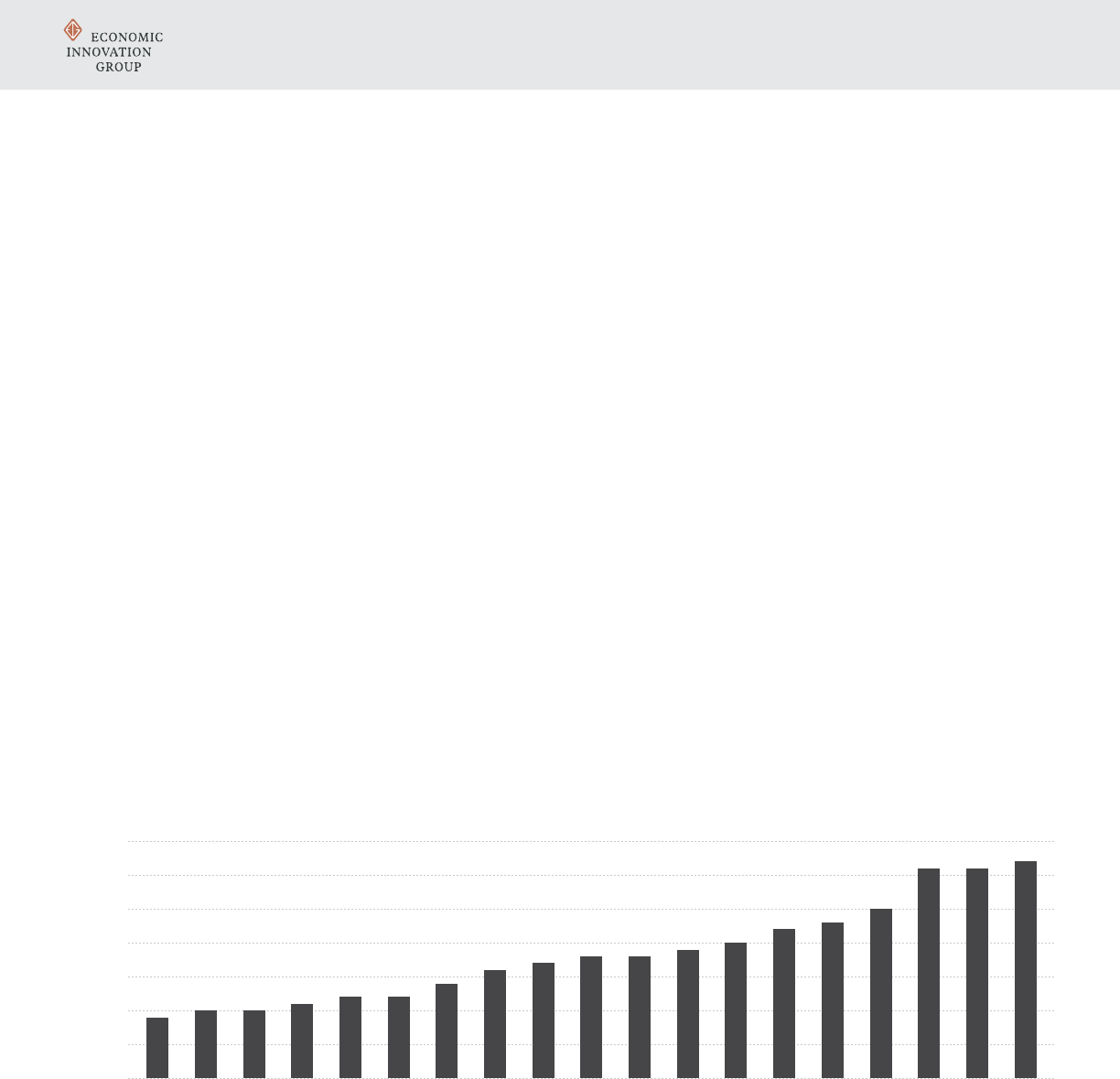

Figure 1. Probability of Signing a Non-Compete Agreement (Based on Industry)

25%

15%

30%

35%

20%

10%

5%

0%

Agriculture

Accommodation, Food

Arts, Entertainment

Construction

Real Estate

Transportation, Warehousing

Retail

Other Services

Mgmt. of Companies

Healthcare

Education

Mining

Utilities

Manufacturing

Admin Support, Waste Mgmt.

Finance and Insurance

Wholesale

Prof. Scientific, Technical

Information

9%

10%

10%

11%

12% 12%

14%

16%

17%

18%

18%

19%

20%

22%

23%

25%

31%

31%

32%

Non-competes have become common across different sectors and skill levels. Among

executives, their use increased from 75% in 1996 to 86% in 2009.

23

At the other end of

the employment spectrum, it was first reported in 2014 that firms were also asking

minimum-wage sandwich makers, camp counselors, and unpaid interns to sign non-

competes.

24

A study of 11,500 workers in 2014 found these patterns hold across the

Source: Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Non-Competes in the U.S. Labor Force”

5

U.S. workforce: Nearly 50% of those earning more than $150k were bound by a non-

compete, while 14% of workers earning less than $40,000 a year were bound. This

study also found that non-competes tend to cluster in high-skill jobs and industries,

although they are prevalent across all occupations, industries, and income levels.

25

Other occupation-specific studies have corroborated these results, showing that 30%

of hairstylists are bound by non-competes, 43% of engineers, and 45% of physicians.

26

Firms are increasingly pursuing action against workers over non-competes as well:

Between 2000 and 2018, the number of reported non-compete court cases nearly

doubled.

27

Figure 2. Probability of Signing a Non-Compete Agreement (Based on Occupation)

25%

15%

30%

35%

40%

20%

10%

5%

0%

Farm, Fish, Forestry

Legal

Grounds Maintenance

Food Prep, Serving

Construction

Transportation, Mat. Moving

Office

Community, Social Services

Sales

Production

Physician, Technical

Education, Training

Management

Architecture, Engineering

Installation, Repair

Life, Physical, Social Sciences

Protective Services

Arts, Entertainment

Personal Care

Business, Finance

Healthcare Support

Computer, Mathematical

35%

30%

26%

25%

23%

22%

21%

19%19%

19%

18%

16%16%

15%

14%

12%12%

11%

11%

10%

6%

36%

Figure 3. Probability of Signing a Non-Compete Agreement (Based on Income)

25%

15%

30%

35%

45%

40%

50%

20%

10%

5%

0%

46%

32%

33%

27%

25%

21%

15%

12%

$0-$20 $20-$40

$40-$60

$60-$80 $80-$100

$100-$120

$140-$150 $150+

Annual Earnings (thousands)

Source: Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Non-Competes in the U.S. Labor Force”

Source: Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Non-Competes in the U.S. Labor Force”

6

The question of whether workers willingly consent to non-competes or

whether they have no practical ability to turn them down due to limited

bargaining power lies at the heart of the current policy debate.

Are non-competes enforceable in court?

Non-competes are agreed to by workers and thus there is a presumption of voluntary

assent based on the notion that workers would not agree to such restrictions unless

they were getting something of equal or greater value in return. The question

of whether workers willingly consent to non-competes or whether they have no

practical ability to turn them down due to limited bargaining power lies at the heart

of the current policy debate. It joins a bigger and centuries-long question about

whether and under what circumstances restraints on trade, such as a non-compete,

may be permissible, given the harm such measures can inflict on the economy.

28

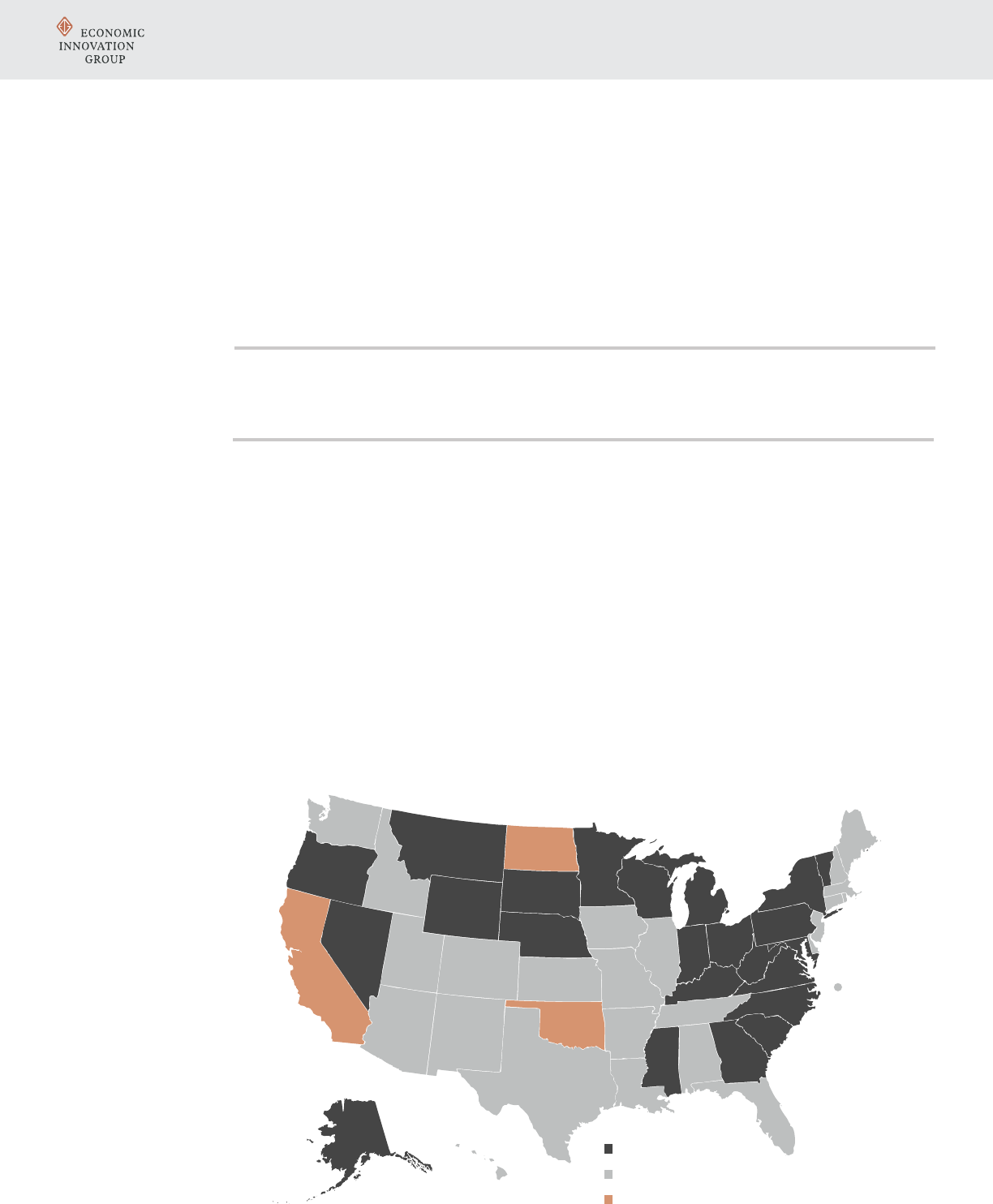

This debate has led to a patchwork of non-compete laws across states, where courts

generally decide whether a given non-compete satisfies a reasonableness test. On

one end are a small number of states that generally do not enforce non-compete

agreements, like California, which adopted its ban in 1872.

29

On the other are states

like Florida, whose current statute (passed in 1996) instructs courts examining a non-

compete case to “not consider any individualized economic or other hardship that

might be caused to the person against whom enforcement is sought.”

30

Most states

fall closer to Florida than they do to California, as documented in the map below,

which presents an up-to-date look at state policies. In one recent case, for example, a

Massachusetts court enforced a non-compete against a janitorial supervisor making

$18/hr, although the company dropped the lawsuit after significant public outcry.

31

Figure 4. Non-Compete Enforcement by State

Permitted

Permitted with Exceptions

Washington, DC

Banned

Source: Beck Reed Riden 50 State Non-compete Chart

7

Theory and Evidence

A note on the difference between non-compete enforceability and non-compete use

The literature on non-competes covers two related but different dimensions: (1) the

effects of signing a non-compete, and (2) the effects of state policies that enforce

non-competes. This distinction is important for several reasons. Most importantly,

the studies of non-compete enforceability are the most relevant for lawmakers,

because lawmakers choose the law but do not dictate the terms of private

employment contracts (though several new proposals seek to impose penalties

on firms caught using unenforceable non-competes). Studies of enforceability

also happen to be far more numerous. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the

mere inclusion of a non-compete provision, regardless of its enforceability,

produces chilling labor market effects. For example, in one study nearly 40% of

workers reported turning down a job offer from a competitor because of a non-

compete, even though they worked in states where such provisions were entirely

unenforceable (subsequent work shows the workers were largely unaware of the

law).

32

In many ways, as more data becomes available, these two streams within the

non-compete literature are converging, although there are still important gaps and

puzzles that require reconciliation.

The Contracting Process

Those against the use or enforcement of non-competes emphasize that labor

markets are fraught with frictions, incomplete information, and unscrupulous

employers interested in reducing turnover or holding wages down. They suggest

that, in practice, non-competes are often implemented in ways that limit employee

bargaining power, such as offering the non-compete on the first day of work, or are

asked of vulnerable workers who have no other choice but to sign. In this view, firms

wield substantial bargaining power and can simply tack on a non-compete to the

employment contract without necessarily compensating the worker fairly for their

postemployment concessions.

In contrast, the pro-non-compete perspective privileges investment protection

and private contracting. It holds that enforceable non-competes are necessary for

the investment in valuable information that workers could otherwise appropriate

for themselves by moving to or starting a competitor. With an enforceable non-

compete, firms may invest more in their workers and trust them with access to more

valuable information, which ultimately may make them more productive in their

job. Moreover, proponents argue that labor markets are generally competitive and

that workers have the power to negotiate these contracts.

Evidence on the hiring and contracting process suggests that the signing of a non-

compete is rarely a bargained outcome, however. One nationally representative

study finds that less than 10% of workers negotiate over the terms of the non-

compete or for other benefits in exchange for signing.

33

When asked to sign a non-

Evidence on the hiring and contracting process suggests that

the signing of a non-compete is rarely a bargained outcome.

8

compete, 93% of workers simply read and sign. Moreover, more than 85% of workers

report that firms did not offer any additional benefits in exchange for signing the

non-compete. Transparency concerns also loom large: two studies find that 30-

40% of workers who are asked to sign non-competes are first asked after they have

already accepted the job, often on the first day when the worker has already turned

down other job offers and may be in a weakened bargaining position.

34

The distinctions in these arguments can help us consider how non-competes might

differentially impact three separate groups.

1. Executives: Those who have extensive and intimate firm knowledge, access to

sophisticated legal counsel, and who can effectively negotiate in and out of

these sorts of provisions. This group is perhaps least susceptible to harm due to

non-competes.

2. Workers engaged in innovative activities: Individuals involved in knowledge-

creation often possess substantial amounts of tacit knowledge acquired through

their work, education, and experience. These workers are especially important

for their role in spurring innovation and entrepreneurship, which in turn lead to

positive, economy-wide spillovers and increases in aggregate productivity.

35

3. Low-wage workers: These workers likely have little bargaining power, and they

may need the job to put food on the table tomorrow. They also have little access

to legal counsel and are thus likely sign a non-compete when asked.

Worker Mobility, Hiring, and Entrepreneurship

Since non-competes function by limiting the available set of job options for workers,

they can influence both where individuals go when they leave, and if they leave in

the first place. The evidence shows that non-compete-bound workers stay in their

jobs longer. In one study, being bound by a non-compete is associated with an 11%

increase in job tenure.

36

Research on different state policies finds corroborating

evidence across several samples and empirical methods. For example, the 2015

Hawaii ban on non-competes for tech workers increased employee mobility in the

sector by 11%.

37

Similar results are found for executives, patent holders, and the

universe of individuals with LinkedIn records.

38

A preliminary analysis of Oregon’s

2008 ban on non-competes for hourly workers finds similar results.

39

The flip side of non-competes impeding employee mobility is preventing firms from

hiring the candidates they would like to hire. Four studies find evidence consistent

with the notion that firms have trouble hiring workers in higher enforceability

regimes.

40

And it appears that young firms are hit particularly hard: One study finds

that in higher enforceability states, new firms start with fewer employees, are more

likely to die in their first 3 years, and that even the firms that survive stay smaller in

their first 5 years.

41

In addition to extending employment durations and making it challenging to hire,

non-competes also have the potential to influence where and in which industry

individuals work. Two studies suggest that individuals bound by non-competes are

redirected to other industries, including 11% of those who have ever signed one.

42

Other studies find that tech workers and patent holders are more likely to leave

states that enforce non-competes.

43

9

Since covered workers are also restricted from starting a new

firm if they develop a novel idea or devise a better way of doing

business, non-competes can stymie entrepreneurship.

Figure 5. Job Separation in Hawaii Before and After Non-Competes Ban

.14

0.07

Q2 2013

Q3 2013

Q4 2013

Q1 2014

Q2 2014

Q3 2014

Q4 2014

Q1 2015

Q2 2015

Q3 2015

Q4 2015

Q1 2016

Q2 2016

Q3 2016

Q4 2016

0.09

.11

0.08

.1

.12

.13

Separation Rate

Ban Implemented

Hawaii Counterfactual (no ban) Hawaii

Source: Balasubramanian, et al., 2018. Counterfactual represents a synthetic estimate created by matching Hawaii’s pre-ban trends with weighted

combinations of other states’ trends. The sample is limited to only the tech industry.

Since covered workers are also restricted from starting a new firm if they develop

a novel idea or devise a better way of doing business, non-competes can stymie

entrepreneurship. In total, seven recent studies examined the relationship

between non-compete enforceability and entrepreneurship, finding generally the

enforceability of non-competes dampens new firm creation.

44

One study found that

greater enforceability of non-competes reduced new firm entry by 18%.

45

The knock-on effects of these mobility and entrepreneurship patterns on the

productivity, innovativeness, and competitive intensity of the economy seem clear.

If workers are prevented from applying their skills in the fields in which they are

most qualified, or in the states where they want to work, or in the new firms they

want to found, then it might be expected that productivity and wages fall, and

aggregate employment suffers, since new firms contribute disproportionately to job

creation.

46

Nevertheless, there are some countervailing arguments for how non-

competes may spur investment, productivity advances, and wage increases at the

individual or firm level. I now turn to those arguments and the evidence.

Investment and Innovation

Firms may invest more in R&D and other innovation-related activities if they

believe a competitor is less likely to capture some of their knowledge investment

thanks to non-competes. For this reason, non-competes and their enforceability

can spur firm-level investment and innovation. However, in addition to the fact that

non-competes can push individuals into jobs for which they are less well-suited, the

10

churn of skilled workers among firms is also a central ingredient to the process of

innovation.

47

By reducing employee mobility, the proliferation and enforcement of

non-compete agreements may threaten innovation economy-wide as the potential

for ideas to recombine and cross-pollinate across firm boundaries also declines.

The empirical literature generally bears out this tension, though there is some

disagreement. The enforceability of non-competes is associated with more

firm-sponsored training of workers, increases in net capital investment rates,

the exploration of new fields, and the creation of riskier patents.

48

However the

mobility-inhibiting effects of non-compete enforceability also dampens knowledge

flows and makes venture capital less effective in spurring the creation of new

patents and employment.

49

Wages

The theoretical reasons why workers’ wages may suffer from non-competes and

their enforceability are clear: Job-to-job mobility is critical for earnings growth,

50

and if non-competes shield workers from accepting outside offers then they will not

experience the benefits of within-industry competition for their skills. Moreover, if

workers are pushed to industries in which they are less productive, then their wages

may also fall.

51

On the other hand, there are countervailing theoretical reasons for

why non-competes or their enforceability could be neutral or even beneficial for

workers. For example, if labor markets are perfectly competitive, then workers

should receive sufficient compensation such that agreeing not to compete in the

future serves in their best interest today. In addition, if the firm invests more

because of a non-compete and the worker is more productive as a result, then the

worker’s wages may rise. Which forces appear to dominate?

Several recent studies have examined the relationship between non-compete

enforceability and wages, and the findings generally suggest that workers in states

that enforce non-competes earn less than equivalent workers in states that do

not enforce non-competes.

52

One recent study finds that the Hawaii ban on non-

competes for technology workers increased new-hire wages by 4%. The same study

also documents that technology workers who start jobs in an average enforceability

state have 5% lower wages even eight years later relative to equivalent workers in

non-enforcing states.

53

Another two studies looking at broader segments of the labor

market document that the negative wage effects of non-compete enforceability are

generally borne by those with less education.

54

Several recent studies have examined the relationship between non-

compete enforceability and wages, and the findings generally suggest

that workers in states that enforce non-competes earn less than

equivalent workers in states that do not enforce non-competes.

By reducing employee mobility, the proliferation and enforcement

of non-compete agreements may threaten innovation

economy-wide as the potential for ideas to recombine and

cross-pollinate across firm boundaries also declines.

11

The studies cited above highlight how living in a state that more vigorously enforces

non-competes hurts wages, but they do not address the effects of actually signing

a non-compete. Identifying the latter effect is more challenging because non-

competes are more prevalent the higher one goes up the pay scale. Nevertheless,

several studies of high-skill occupations look specifically at the signing a non-

compete and find that CEOs and physicians who do sign non-competes earn more

than those who do not sign.

55

However, a separate study identifies an important transparency issue for

determining the ultimate wage effect of a non-compete. When firms delay notifying

workers about the non-compete until after the worker accepts the job, those workers

do not receive any wage premiums. They are also less satisfied and stay longer in

their jobs.

56

Looked at in its entirety, the existing body of research produces the somewhat

paradoxical result that non-competes can deliver wage premiums to individual

workers (in some cases) while enforceability itself generally depresses wages in

the market. How can both be true? The research does not yet provide a definitive

answer, but negative externalities are a prime suspect. A recent study analyzes the

mobility and wage effects of the incidence and enforceability of non-competes

across state-industry combinations for workers who are and are not bound by the

agreements.

57

The results suggest that relative to a state where non-competes are

not enforceable, a 10% rise in the industry incidence of non-competes is associated

with 4% lower wages among the unconstrained, 13% longer tenures, and a 16%-

24% decrease in the relative rate of job offers. Moreover, these negative effects are

Figure 6. New Hire Wages In Hawaii Before and After Non-Competes Ban

8.85

8.5

Q2 2013

Q3 2013

Q4 2013

Q1 2014

Q2 2014

Q3 2014

Q4 2014

Q1 2015

Q2 2015

Q3 2015

Q4 2015

Q1 2016

Q2 2016

Q3 2016

Q4 2016

8.6

8.7

8.55

8.65

8.75

8.8

Average Quarterly Earnings for New Hires (Log Scale)

Ban Implemented

Hawaii Counterfactual (no ban) Hawaii

Source: Balasubramanian, et al., 2018. Counterfactual represents a synthetic estimate created by matching Hawaii’s pre-ban trends with weighted

combinations of other states’ trends. The sample is limited to only the tech industry.

There are many other tools that firms can use to protect their legitimate

business interests that do not explicitly restrict worker freedom.

12

statistically indistinguishable for those constrained by non-competes. Thus, the

evidence suggests that the mass use of enforceable non-competes dampens the

dynamism of the labor market as a whole.

Incumbent Firms

If the mass-use of enforceable non-competes reduces mobility, new firm entry,

and wages within the market, then incumbent firms stand to gain from the lower

turnover costs, lower wages, reduced competition and more secure investments in

knowledge and training. Indeed, one study finds that non-compete enforceability

increases firm value, while another documents that firms in states that enforce non-

competes are more likely to be acquisition targets.

58

Another study finds that larger

firms added more establishments when non-compete enforceability increased, at

the cost of new entrants.

59

Of course, non-competes and their enforceability are not

always good for incumbent firms, as they can impose significant hiring costs, as

demonstrated by the recent spat between HP and Cisco, in which the former tried to

block the latter from hiring its alumni.

60

*

The totality of these relationships raises an important question for policymakers:

Even if in theory a policymaker would prefer to treat private parties’ right to enter

into restrictive covenants as sacrosanct, does the evidence of abuse, negative

outcomes for workers and young firms, and negative externalities on the market as

a whole justify intervention? For an increasing number of public leaders from across

the political spectrum, the answer appears to be yes.

Alternatives Tools

One reason non-competes and no-poach agreements have captured the attention

of reformers is that they are incredibly blunt objects: they prohibit the worker

and thus all of the worker’s accumulated knowledge and skills from being

deployed elsewhere in the industry, even if the present firm’s contributions to that

accumulated set of knowledge and skills is tiny or nonexistent. Equally important,

there are many other tools that firms can use to protect their legitimate business

interests that do not explicitly restrict workers’ freedom to work in their chosen

industry and with their chosen employer. These alternative provisions include

non-disclosure agreements, non-solicitation of client agreements, IP assignment

agreements, and training repayment agreements, to name a few. These provisions

impose restrictions on workers directly targeted to the protectable interests of

the firm – trade secrets, client lists, specialized techniques – while not explicitly

limiting where an individual is free to work. Furthermore, preliminary work finds

that firms already tend to use these contracts in tandem rather than as substitutes.

61

In addition to other provisions, there are also other laws, such as trade secret laws

and patent laws, that firms may use instead of relying on non-compete laws.

Non-competes may have modest strengths relative to some of these alternatives

– for example, a violation is readily observable and thus court proceedings may

evolve more quickly and cheaply – but the research is increasingly clear that they

come with significant costs to workers as a class and to the overall dynamism of

the economy. Simply having a contract that says one cannot work in one’s chosen

13

industry, even if the contract is unenforceable, chills worker mobility.

62

The moral

or philosophical arguments against restricting employee choice have already

turned many lawmakers against non-competes. In light of the growing body of

evidence, many more now question whether the added value of a non-compete to

an employment contract suffices to compensate against the negative side effects.

Reform

As economists continue building the empirical evidence, policymakers show

increasing interest in reform. Many seem to be guided by the simple conviction

that if workers must compete against each other for jobs, then firms must compete

against each other for workers, end of story. Others view the anecdotal evidence

as sufficient proof that employers are abusing their power. Policymakers are also

attuned to research documenting the extent to which non-compete enforceability

curtails wages, employee mobility, and entrepreneurship. Although there is

substantially less evidence on no-poach agreements, it is not much of a stretch

to assume that such provisions are generally harmful given that workers have no

opportunity to agree to them.

In recent years, more than 20 federal and state policy proposals have sought to

combat the deleterious effects of non-competes and no-poach agreements, with

a handful of states passing new laws (the federal proposals have not yet been

passed or voted on). The approaches generally fall into two big buckets: Reforms

targeted at putting conditions on the use of such agreements, on the one hand, and

efforts to ban the tools outright and completely, on the other. Policy options under

consideration include:

• Ensuring transparency: These policies seek to ensure that the contracting

process is as transparent and fair as possible. This includes notifying the

worker about the firm’s desire to use a non-compete sufficiently early for the

worker to consider the restrictions before accepting a job. If the firm would like

to ask workers who have already joined the firm to agree to a non-compete, it

must come with a bona-fide advancement within the firm. Examples include

Massachusetts’ new non-compete law.

63

• Consideration and Garden Leave: These policies seek to ensure that workers are

partially compensated for what they give up. The notion of consideration is that

workers are paid something extra—a bonus or a higher wage, for example—in

exchange for signing a non-compete. “Garden leave” provisions require the

firm to pay the worker some portion of her salary while the worker abides by

the non-compete. Such provisions ensure that firms incur a cost to enforce a

non-compete, discouraging over-use and empty enforcement threats. Examples

include Oregon’s 2008 statute.

64

• Refusing to re-write overly broad provisions: Many states will re-write overly

broad non-competes and then enforce them. That is, a court could take a 10 year

non-compete, reduce it to 2 years, and then enforce it. This practice encourages

firms to write broad non-competes because in the worst case the court will still

enforce a pared down version. However, the conditions in the non-compete may

still chill workers from taking jobs or starting companies because they view the

overly broad restrictions as enforceable.

14

• Ban on non-competes for low-wage workers: These policies are generally justified

by the argument that low-wage or hourly workers have little bargaining power,

are the least likely to possess information that could damage the firm, and are

most susceptible to threats over the enforcement of non-competes because

they may not be able to afford legal assistance. Examples include the MOVE

Act, the Freedom to Compete Act, and recent bills in Illinois, Oregon, and

Massachusetts.

65

• Ban on non-competes for specific high-skill occupations: In the case of lawyers

(where non-competes are unenforceable in all states) and physicians (where

they are banned in several states), these bans rely on public policy concerns,

such as ensuring that clients and patients have access to legal advice and

healthcare. In the case of tech workers (for whom non-competes were banned

in Hawaii in 2015), the justifications rely on the notion that mobility and

entrepreneurship are good for innovation, as in Silicon Valley.

66

• A complete ban on non-competes: In addition to the justifications for the low-

wage and high-skill bans, this policy more strongly leverages the idea that non-

competes are unnecessarily blunt instruments whose negative mobility and

wage ramifications can spill over to the whole market, and that firms have more

precise ways to protect their legitimate interests without constraining workers’

employment options. On the investment and innovation front, California’s

policy of general non-enforcement, which was adopted in 1872, and the success

of Silicon Valley as the most innovative ecosystem in the country, if not the

world, is often touted as a stark counterexample to the logic that firms need

enforceable non-competes to protect their investments in IP.

67

Recent examples

include a push for the FTC to declare non-competes an unfair method of

competition and classify them as per se illegal under the FTC Act.

68

• A complete ban on no-poach agreements: While no-poach agreements are already

per se illegal, recent efforts to ban them even within franchises have cited the

fact that there is no presumption of assent to the restrictive terms, since workers

likely do not even know they exist. The End Employer Collusion Act is a recent

example of a federal effort to eradicate these practices.

69

Conclusion

Amidst the backdrop of falling economic dynamism, today’s heightened policy focus

on non-competes and no-poach agreements reflects a recognition of the growing

empirical research that such provisions often function to prevent workers from

earning what a competitive market would dictate and to stymie the natural labor

market churn that keeps the economy healthy. Few issues bring progressives who care

about worker protections together with conservatives who believe in the power of free

and fair competition as has the proliferation of these restrictive labor agreements.

The result is a rare consensus on the need for reform that has unified state and federal

politicians from both sides of the aisle, state AG offices, and federal antitrust agencies.

This briefer is intended to further inform the debate and present the latest empirical

research in order to guide reform efforts at all levels of government.

15

For Further Reading

1. Krueger and Ashenfelter 2018, “Theory and Evidence on Employer Collusion in

the Franchise Sector.” NBER Working Paper No. 24831.

2. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara 2019, “Non-Competes in the U.S. Labor Force.”

University of Michigan Law & Econ Research Paper No. 18-013, 2019.

3. Marx 2011, “The Firm Strikes Back: Non-Compete Agreements and the Mobility of

Technical Professionals.” American Sociological Review, vol. 76, no. 5, pp. 695-712.

4. Balasubramanian et al. 2018, “Locked In? The Enforceability of Covenants Not to

Compete and the Careers of High-Tech Workers.” US Census Bureau Center for

Economic Studies Paper No. CES-WP-17-09; Ross School of Business Paper No.

1339.

5. Starr, Balasubramanian, and Sakakibara 2018, “Screening Spinouts? Non-

Compete Enforceability and the Creation, Growth, and Survival of New Firms.”

Management Science, vol. 64, no. 2, pp. v-x, 495-981.

6. Garmaise 2011, “Ties that Truly Bind: Noncompetition Agreements, Executive

Compensation, and Firm Investment.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and

Organization, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 376-425.

Endnotes

1. Molloy, Raven, Christopher L. Smith, Riccardo Trezzi, and Abigail Wozniak, “Understanding Declining Fluidity

in the U.S. Labor Market.” Brookings Institution, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/

molloytextspring16bpea.pdf. Also see: “Dynamism in Retreat.” Economic Innovation Group, 2017, https://eig.org/

dynamism.

2. Mishel, Lawrence, Elise Gould, and Josh Bivens, “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts.” Economic Policy Institute,

2015, https://www.epi.org/publication/charting-wage-stagnation/. For an assessment from a more conservative

perspective that largely corroborates the same trends, see Strain, Michael “The Link Between Wages and

Productivity is Strong” at https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-Link-Between-Wages-and-

Productivity-is-Strong.pdf.

3. Starr, Evan, J.J. Prescott, and Norman Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.” U of Michigan Law &

Econ Research Paper No. 18-013, 2019.

4. Girls on the Run of Silicon Valley Volunteer Coach Contract: “As a coach and volunteer for Girls on the Run of

Silicon Valley, I agree to the following: 1.) I will not deliver the Girls on the Run program or any similar program

unless I am working as an employee or volunteer of Girls on the Run. 2.) I may not create or help develop a

program that has similar goals and structure to that of Girls on the Run International within a two year period

of my involvement with Girls on the Run.” Source: Author’s research. This contract is clearly unenforceable in

California under Business and Professions Code Section 16600.

5. Krueger, Alan B., Orley Ashenfelter, “Theory and Evidence on Employer Collusion in the Franchise Sector.”

NBER Working Paper No. 24831, 2018.

6. See California Business and Professions Code Section 16600, which reads “Every contract by which anyone is

restrained from engaging in a lawful profession, trade or business of any kind is to that extent void.” Notably,

California will enforce covenants not to compete incident to a sale of business.

16

7. See the March 2016 Treasury Report, “Non-Compete Contracts: Economic Effects and Policy Implications” at

https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/economic-policy/Documents/UST%20Non-competes%20Report.pdf.

See the White House 2016 Report “Non-Compete Agreements: Analysis of the Usage, Potential Issues, and State

Responses” at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/non-competes_report_final2.pdf. With

regards to new state and federal policy proposals, see https://www.faircompetitionlaw.com/. Some recent laws

include the Workforce Mobility Act (see: https://www.booker.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=760; https://www.

warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/warren-murphy-wyden-introduce-bill-to-ban-unnecessary-and-

harmful-non-compete-agreements) and Massachusetts’s new law (https://www.masstlc.org/a-new-era-of-ma-

non-compete-law-begins/).

8. For information on the AG investigations and the role of AGs generally, see Madigan and Flanagan 2018,

“Overuse of Non-Competition Agreements: Understanding How They Are Used, Who They Harm, and What

State Attorneys General Can Do to Protect the Public Interest” at https://lwp.law.harvard.edu/files/lwp/files/

webpage_materials_papers_madigan_flanagan_june_13_2018.pdf. For more details, see https://www.nytimes.

com/2017/10/25/business/economy/illinois-non-compete.html.

9. For DOJ HR Guidance, see: https://www.justice.gov/atr/file/903511/download.

10. Chinn, Lloyd B., Colin Kass, Laura Fant, and Myra Din, “DOJ Announces First Settlement Under Trump

Administration Regarding ‘No-Poach’ Agreement.” Law and the Workplace, Apr. 19, 2018, https://www.

lawandtheworkplace.com/2018/04/doj-announces-first-settlement-under-trump-administration-regarding-no-

poach-agreement. For DOJ No-poach case, see: https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/2018/04/11/doj-brings-

first-no-poach-prosecution-since-issuing-antitrust-guidance-for-hr-professionals/?slreturn=20190017224217.

11. See https://www.bna.com/ftc-democrat-urges-n73014482473/.

12. Rohit Chopra (FTC commisioner) remarks on non-competes and other issues related to competition in the

labor market: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1408196/chopra_-_comment_to_

hearing_1_9-6-18.pdf.

13. Lowensohn, Josh, “Amazon does an about-face on controversial warehouse worker non-compete contracts.” The

Verge, Mar. 27, 2015, https://www.theverge.com/2015/3/27/8303229/amazon-reverses-non-compete-contract-rules.

14. Abrams, Rachel, “8 Fast-Food Chains Will End ‘No-Poach Policies.” New York Times, Aug. 20, 2018, https://www.

nytimes.com/2018/08/20/business/fast-food-wages-no-poach-franchisees.html.

15. See, for example, Council of Economic Advisors October 2016 Issue Brief, “Labor Market Monopsony: Trends,

Consequences, and Policy Responses” available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/

page/files/20161025_monopsony_labor_mrkt_cea.pdf.

16. For the concentration statistics based on vacancies, see: Azar, José A., et al. “Concentration in US labor markets:

Evidence from online vacancy data.” NBER Working Paper No. w24395, 2018. For the relationship with wages,

see: Azar, José, Ioana Marinescu, and Marshall I. Steinbaum, “Labor market concentration.” NBER Working

Paper No. w24147, 2017. See also: Benmelech, Efraim, Nittai Bergman, and Hyunseob Kim, “Strong employers

and weak employees: How does employer concentration affect wages?” NBER Working Paper No. w24307, 2018.;

Qiu, Yue and Aaron J. Sojourner, “Labor-Market Concentration and Labor Compensation.” IZA Discussion Papers

12089, 2019.

17. See, for example, recent reports from The Hamilton Project and Center for American Progress, which also

provide an excellent overview of the issues around non-competes. These include Marx, Matt “Reforming Non-

competes to Support Workers,” Hamilton Project Policy Proposal 2018-04; Krueger Alan, and Eric Posner, “ A

Proposal for Protecting Low-Income Workers from Monopsony and Collusion,” Hamilton Project Policy Proposal

2018-05; and Walter, Karla, “The Freedom to Leave: Curbing Noncompete Agreements to Protect Workers and

Support Entrepreneurship, ”Center for American Progress.

18. Woodman, Spencer, “Exclusive: Amazon makes even temporary warehouse workers sign 18-month non-

competes.” The Verge, Mar. 26, 2015, https://www.theverge.com/2015/3/26/8280309/amazon-warehouse-jobs-

exclusive-noncompete-contracts.

19. Rizzi, Corrado, “McDonald’s Facing Antitrust Class Action Over Alleged Wage-Suppression Conspiracy.”

ClassAction.org, Jun. 29, 2017, https://www.classaction.org/blog/mcdonalds-facing-antitrust-class-action-over-

alleged-wage-suppression-conspiracy.

20. The gray area occurs because, in the franchise context, it’s not clear if different establishments owned by

separate franchises should be considered competing entities.

21. Krueger and Ashenfelter, “Collusion in the Franchise Sector.”

17

22. “Justice Department Requires Knorr and Wabtec to Terminate Unlawful Agreements Not to Compete for

Employees.” Department of Justice, press release Apr. 3, 2018.; Hollister, Sean, “Steve Jobs personally asked

Eric Schmidt to stop poaching employees, and other unredacted statements in a Silicon Valley scandal.” The

Verge, Jan. 27, 2012, https://www.theverge.com/2012/1/27/2753701/no-poach-scandal-unredacted-steve-jobs-eric-

schmidt-paul-otellini.

23. Bishara, Norman D., Kenneth J. Martin, and Randall S. Thomas, “An Empirical Analysis of Noncompetition

Clauses and Other Restrictive Postemployment Covenants.” Vanderbilt Law Review, vol. 68, no. 1, 2015.

24. Greenhouse, Steven, “Non-compete Clauses Increasingly Pop Up in Array of Jobs.” New York Times, Jun. 8, 2014,

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/business/non-compete-clauses-increasingly-pop-up-in-array-of-jobs.

html.

25. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.” A smaller but more recent survey finds

similar numbers: Krueger and Posner, “ A Proposal for Protecting Low-Income Workers from Monopsony and

Collusion,” Hamilton Project Policy Proposal 2018-05. A last survey of workers in Utah finds similar numbers:

Cicero (2017), available at https://slchamber.com/noncompetestudy/.

26. For engineers, see: Marx, Matt, “The Firm Strikes Back: Non-Compete Agreements and the Mobility of Technical

Professionals.” American Sociological Review, vol. 76, no. 5, 2011, pp. 695-712. For physicians, see: Lavetti, Kurt,

Carol Simon, and William D. White, “The Impacts of Restricting Mobility of Skilled Service Workers: Evidence

from Physicians.” Journal of Human Resources, 2018. For hairstylists, see: Johnson, Matthew S., Michael Lipsitz,

“Why are Low-Wage Workers Signing Non-compete Agreements?” 2017.

27. According to Beck, Reed and Riden, the number of non-compete cases in 2000 was 527, compared to 993 in 2018.

See their year by year chart at https://www.faircompetitionlaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Non-compete-

and-Trade-Secret-Cases-Survey-Graph-20190113-Data-and-Charts.jpg.

28. The Dyer’s case in 1414 is typically looked to as the first judgement against enforcing a non-compete. Review

available here: https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1189&context=bjell.

29. Gilson, R.J., 1999. “The legal infrastructure of high technology industrial districts: Silicon Valley, Route 128, and

covenants not to compete.” NYU Law Rev., 74, p.575.

30. See: http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0500-0599/0542/

Sections/0542.335.html, Section (1)(g) of 542.335 Valid restraints of trade or commerce.

31. Shubber, Kadhim, “Cushman v the Cleaner: The fight over non-competes.” Financial Times, Oct. 16, 2018, https://

www.ft.com/content/b69d30-ce44-11e8-b276-b9069bde0956.

32. For evidence on the chilling effect of non-competes, see: Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S.

Labor Force.” For evidence on what individuals know about their state laws, see: Prescott, J.J., and Evan Starr,

“The Accuracy and Effects of Beliefs About Non-Compete Laws: Evidence from an Information Experiment.”

Working paper 2019.

33. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.”

34. These two studies are Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.”; Marx, “The Firm

Strikes Back.”

35. For a summary of the issues with knowledge workers, see: Lobel, Orly and James Bessen, “Stop Trying to Control

How Ex-Employees Use Their Knowledge.” Harvard Business Review, Oct. 9, 2014, https://hbr.org/2014/10/stop-

trying-to-control-how-ex-employees-use-their-knowledge.

36. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.” In another study, physicians who agree to

non-competes were found to have 12% longer job spells than unbound physicians. See Lavetti, Simon, and White,

“The Impacts of Restricting Mobility.” Note that the Starr, Prescott, and Bishara study found that for the average

labor force participant, the effects of a non-compete on job tenure and the likelihood of leaving the industry are

not statistically different in states that do not enforce non-competes.

37. Balasubramanian, Natarajan, Jin Woo Chang, Mariko Sakakibara, Jagadeesh Sivadasan, and Evan Starr, “Locked

In? The Enforceability of Covenants Not to Compete and the Careers of High-Tech Workers.” US Census Bureau

Center for Economic Studies Paper No. CES-WP-17-09; Ross School of Business Paper No. 1339, Dec. 13, 2018.

38. For patent holders, see Marx, M., Strumsky, D. and Fleming, L., 2009. “Mobility, skills, and the Michigan non-

compete experiment.” Management Science, 55(6), pp.875-889. For executives, see Garmaise, Mark J., “Ties

that Truly Bind: Noncompetition Agreements, Executive Compensation, and Firm Investment.” The Journal

of Law, Economics, and Organization, vol. 27, no. 2, 2011, pp. 376-425. For tech workers, see Fallick, Bruce,

Charles A. Fleischman, and James B. Rebitzer, “Job-hopping in Silicon Valley: some evidence concerning the

microfoundations of a high-technology cluster.” The Review of Economics and Statistics vol. 88, no. 3, 2006, pp.

472-481. For workers on LinkedIn, see Jeffers, Jessica, “The Impact of Restricting Labor Mobility on Corporate

Investment and Entrepreneurship.” Working paper.

18

39. Lipsitz, Michael and Evan Starr, “Low Wage Workers and the Enforceability of Noncompetes.”

40. Starr, Evan, Martin Ganco, Benjamin A. Campbell, “Strategic human capital management in the context of

cross-industry and within-industry mobility frictions.” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 39, no. 8, 2018, pp.

2226-2254.; Ewens, Michael, and Matt Marx, “Founder Replacement and Startup Performance.” The Review

of Financial Studies, vol. 31, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1532-1565.; Starr, Evan, Natarajan Balasubramanian, and Mariko

Sakakibara, “Screening Spinouts? Non-Compete Enforceability and the Creation, Growth, and Survival of

New Firms.” Management Science, vol. 64, no. 2, 2018, pp. v-x, 495-981.; Balasubramanian, Natarajan, Mariko

Sakakibara, Evan Starr, and Ramanathan, “The Effect of Curtailing the Enforceability of Physician Non-compete

Agreements on Healthcare Availability.” Working paper.

41. Starr, et al., “Screening Spinouts? Non-Compete Enforceability and the Creation, Growth, and Survival of New

Firms.”

42. Marx, “The Firm Strikes Back.”; Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.” A third

study documents that after Michigan started enforcing non-competes in 1984 that technical workers were more

likely to switch industries: Berger, T. and Frey, C.B., 2017. “Regional technological dynamism and noncompete

clauses: Evidence from a natural experiment.” Journal of Regional Science, 57(4), pp.655-668.

43. Marx, Matt, Jasjit Singh, and Lee Fleming, “Regional disadvantage? Employee non-compete agreements and

brain drain.” Research Policy, vol. 44, no. 2, 2015, pp. 394-404.; Balasubramanian, et al., “Locked In?”

44. Starr, et al., “Screening Spinouts?”; Stuart, Toby E., and Olav Sorenson, “Liquidity Events and the Geographic

Distribution of Entrepreneurial Activity.” Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 2, 2003, pp. 175-201.;

Samila, Sampsa, and Olav Sorenson, “Non-Compete Covenants: Incentives to Innovate or Impediments

to Growth.” Management Science, vol. 57, no. 3, 2011.; Balasubramanian, et al., “The Effect of Curtailing

Enforceability.”; Marx, Matt, “Punctuated Entrepreneurship (Among Women),” working paper. One study finds

no effects of non-compete enforceability on entrepreneurship: Carlino, Gerald, “Do Non-Compete Covenants

Influence State Startup Activity? Evidence from the Michigan Experiment,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

working paper 17-30.

45. Jeffers, “The Impact of Restricting Labor Mobility.” Nevertheless, there are some discrepancies in the growing

literature.

46. Samila and Sorenson, “Non-Compete Covenants: Incentives to Innovate or Impediments to Growth.”

47. Tambe, Prasanna, and Lorin M. Hitt, “Job Hopping, Information Technology Spillovers, and Productivity

Growth.” Management Science, vol. 60, no. 2, 2014, pp. 338-355.

48. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.” Conti, Raffaele, “Do Non-Competition

Agreements Lead Firms to Pursue Risky R&D Projects?” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 35, no. 8, 2014, pp.

1230-1248.; Arts, Sam, and Lee Fleming, “Paradise of Novelty – Or Loss of Human Capital? Exploring New Fields

and Inventive Output.” Organization Science, vol. 29, no. 6, 2018, pp. 989-1236.; Starr, Evan “Consider This:

Training, Wages, and the Enforceability of Covenants Not to Compete.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review

(forthcoming).; Jeffers, “The Impact of Restricting Labor Mobility.”; Shi, Liyan, “Restrictions on Executive

Mobility and Reallocation: The Aggregate Effect of Non-Competition Contracts.” Working paper. However,

there is another study that documents a negative relationship between non-compete enforceability and firm

investment per capita: Garmaise, “Ties that Truly Bind.”

49. Samila and Sorenson, “Non-Compete Covenants.”; Belenzon, Sharon, and Mark Schankerman, “Spreading the

Word: Geography, Policy, and Knowledge Spillovers.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 95, no. 3, 2013,

pp. 884-903.

50. See Topel, Robert H., and Michael P. Ward, “Job Mobility and the Careers of Young Men.” Quarterly Journal of

Economics, vol. 107, no. 2, 1992, pp. 439-470, noting that wage gains at job changes account for at least one third

of early career wage growth.

51. One study finds that after Michigan started enforcing non-competes the workers who switched industries earned

lower wages relative to a set of control states: Berger and Frey, “Regional dynamism and noncompete clauses.”

52. Garmaise, “Ties that Truly Bind.”; Starr, “Training, Wages, and the Enforceability of Covenants Not to Compete.”

53. Balasubramanian, et al., “Locked In?”

54. Starr, “Training, Wages, and the Enforceability of Covenants Not to Compete.”; Lipsitz and Starr, “Low Wage

Workers and the Enforceability of Noncompetes.”

19

55. One study finds that executives are worse off in states that enforce non-compete agreements: Garmaise, “Ties

that Truly Bind.”; Kini, Omesh, Ryan Williams, and Sirui Yin, “Restrictions on CEO Mobility, Performance-

Turnover Sensitivity, and Compensation: Evidence from Non-Compete Agreements.” Working paper.; Cadman,

Brian D., John L. Campbell, and Sandy Klasa, “Are Ex-Ante CEO Severance Pay Contracts Consistent with

Efficient Contracting?” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, vol. 51, no. 3, 2016, pp. 737-769.; Goldman,

Eitan Moshe, and Peggy Peiju Huang, “Contractual vs. Actual Separation Pay Following CEO Turnover.”

Management Science, vol. 61, no. 5, 2014.; Shi, “Restrictions on Executive Mobility.” A final paper shows that

executives can overcome the unenforceability of non-competes through strategically ambiguous contracting

practices: Sanga, Sarath 2018, “Incomplete Contracts: An Empirical Approach,” Journal of Law, Economics, and

Organization 2018.

56. One nationally representative study finds that workers bound by non-competes earn 6% higher wages, but that

these wage gains are not shared equally across all non-compete signers. In particular, the wage gains accrued to

those provided with early notice of the non-compete, and not to those who received notice of the non-compete

after accepting their job offer. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.”

57. Starr, Evan, Justin Frake, and Rajshree Agarwal, “Mobility Constraint Externalities.” Organization Science

(forthcoming).

58. Younge, Kenneth A., and Matt Marx, “The Value of Employee Retention: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.”

Journal of Economics & Management Strategy vol. 25, no. 3, 2016, pp. 652-677.; Younge, Kenneth A., Tony W.

Tong, and Lee Fleming, “How anticipated employee mobility affects acquisition likelihood: Evidence from a

natural experiment.” Strategic Management Journal vol. 36 no. 5, 2015, pp. 686-708. Garmaise, “Ties that Truly

Bind,” finds no effect on firm value, however.

59. Kang, Hyo, and Lee Fleming, “Non-Competes and Business Dynamism.” Searle Center Working Paper Series

(2017-046).

60. Chandler, Mark, “HP Sues Employees for Leaving – We Challenge HP to Support Employee Freedom.” Cisco

Blogs, Nov. 23, 2011, https://blogs.cisco.com/news/hp-sues-employees-for-leaving.

61. Nunn, Ryan and Evan Starr, “The Co-Adoption of Overlapping Restrictive Employment Provisions,”

forthcoming.

62. Starr, Prescott, and Bishara, “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.”; Prescott and Starr, “Accuracy and Effects of

Beliefs About Non-Compete Laws.”

63. See the Massachusetts’s law at https://www.faircompetitionlaw.com/2018/08/06/massachusetts-new-

noncompete-law-the-text/.

64. See the text of the Oregon statute at https://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/653.295.

65. For the MOVE Act, see: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1504. For the Freedom to

Compete Act, see https://www.rubio.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/7563e7ae-ca85-423b-b3e8-b44ce3b4eb54/1D

C3C59DB28D9D2D273ACEB3087742E4.the-freedom-to-compete-act.pdf. See the Illinois low wage ban (Freedom

to Work Act) at http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/99/PDF/099-0860.pdf. See the Massachusetts’s law at

https://www.faircompetitionlaw.com/2018/08/06/massachusetts-new-noncompete-law-the-text/. See the text of

the Oregon statute at https://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/653.295.

66. Saxenian, A., 1996. Regional advantage. Harvard University Press. Gilson, “The legal infrastructure of high-tech

districts.” Hyde, A., 2003. Working in Silicon Valley: Economic and Legal Analysis of a High Velocity Labor

Market. ME Sharpe, Armonk, New York.

67. Those in the pro-non-compete camp are quick to point out that other states that do not enforce non-competes,

like North Dakota and Oklahoma, are not necessarily known as homes for innovation and entrepreneurship.

See: Barnett, Jonathan, and Ted M. Sichelman, “Revisiting Labor Mobility in Innovation Markets.” US CLASS

Research Paper No. 16-13; USC Law Legal Studies Paper No. 16-15.

68. See: Vaheesan, Sandeep, “Antitrust Law: A Current Foe, but Potential Friend, of Workers.” 2018, https://lwp.law.

harvard.edu/files/lwp/files/webpage_materials_papers_vaheesan_june_13_2018.pdf.

69. See “Booker, Warren Introduce Bill to Crack Down on Collusive ‘No Poach’ Agreements.” Office of Cory Booker

press release, Feb. 28, 2018, https://www.booker.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=760.

About the author

Evan Starr is one of the world’s leading experts on restrictive employment

covenants. His research examining how the use and enforceability of

covenants not to compete affect workers, firms, and regions has appeared

in several leading academic journals in business and economics, and has

been covered by prominent news outlets including the New York Times, the

Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, NPR, and the Financial Times.

Dr. Starr is an Assistant Professor at the University of Maryland, Robert

H. Smith School of Business. He received his B.A. in Economics,

Math, and Spanish from Denison University, and a Master’s and

PhD in Economics from the University of Michigan.

About the Economic Innovation Group (EIG)

The Economic Innovation Group (EIG) is an ideas laboratory and advocacy

organization whose mission is to advance solutions that empower

entrepreneurs and investors to forge a more dynamic American economy.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., EIG convenes leading experts from

the public and private sectors, develops original policy research, and

works to advance creative legislative proposals that will bring new jobs,

investment, and economic growth to communities across the nation.

@InnovateEconomy

@Innovate_Economy

facebook.com/EconomicInnovationGroup

1/4

States Must Act to Protect Workers From Exploitative Noncompete and No-Poach

Agreements

americanprogress.org/article/states-must-act-protect-workers-exploitative-noncompete-no-poach-agreements

An employee places food on the counter at a Port St. Lucie, Florida, restaurant in August 2016. (Getty/UIG/Jeffrey Greenberg)

Despite years of economic growth, many Americans’ pay has not improved. Since the Great Recession, overall wage growth has only slightly

outpaced inflation, and the earnings of African Americans have still not recovered. Meanwhile, business startup rates are falling across all

industries, and many economists argue that this decline is dragging down U.S. innovation and productivity growth. As a result, policymakers

across the United States are interested in reforms to boost worker pay, increase job mobility, and enable Americans to start their own

companies. In particular, state lawmakers are debating actions to protect workers from restrictive employment contracts that keep them locked

in jobs they do not want but cannot leave.

From fast-food workers and check-cashing clerks to physicians and engineers, corporations are increasingly subjecting workers across income

and educational attainment levels to agreements that restrict future employment. One recent survey found that nearly 1 in 5 U.S. workers

report that they are currently subject to a noncompete agreement that prevents them from moving to a competing employer, while another

found that more than half of corporate franchisors require franchisees to sign no-poaching agreements that prevent their workers from moving

between locations.

But the damage of these agreements extends beyond mobility impacts for individual workers. The wages of all workers are lower in states

where corporations have maximal power to enforce noncompete agreements. Moreover, several studies indicate that strengthening

noncompete protections for workers is associated with an increase in patents and firm startups—and that doing so could help new firms to

attract top talent.

Although federal action on this issue is unlikely in the near term, state lawmakers have considerable power to protect low- and middle-wage

workers from abusive employment contracts. For example, Illinois and Massachusetts have enacted laws in recent years to protect low-wage

workers from noncompete agreements, and Washington state Attorney General Bob Ferguson is leading a fight to stop corporate franchisors

from requiring their franchisees to sign no-poach agreements.

This primer—based on a 2019 Center from American Progress report, “The Freedom to Leave: Curbing Noncompete Agreements to Protect

Workers and Support Entrepreneurship”—provides important background for lawmakers and advocates who are interested in strengthening

state-level noncompete and no-poach protections. First, it provides a brief explanation of how noncompete and no-poach contracts are

reducing wages and harming growth. It then details policy recommendations that states can adopt to protect workers from abusive agreements.

Finally, the primer includes a table that illustrates how each state’s existing laws compare with CAP’s recommendations.

How do noncompete and no-poaching agreements restrict workers’ mobility?

A noncompete agreement is a contract that requires a worker to agree not to become an employee of a competing company or start a competing

company for a specific period of time after leaving a firm. Typically, corporations require a worker to sign such an agreement at the start of a

new job or position. Workers often receive little advanced warning of the requirement, usually get no payment during the waiting period, and—

even if they suspect that an agreement is illegal—have little recourse to fight in the courts since legal remedies in these cases typically do not

require employers to pay penalties or back pay to aggrieved workers.

As a result, research finds that these agreements have a significant impact on job mobility. Academic research found that job mobility in

Michigan fell by 8 percent after the state started allowing the enforcement of noncompete agreements. Meanwhile, a 2017 U.S. Census Bureau

paper found that tech workers in states that enforce noncompete agreements had 8 percent fewer jobs over an 8-year period compared with

workers in states that do not allow enforcement of noncompete agreements.

No-poaching agreements lead to similar mobility restrictions on fast-food and other franchise workers, but without workers’ prior knowledge.

These agreements are often included in voluminous and confidential contracts that corporations require individual franchisees to sign in order

to operate a business under the corporation’s name. Workers typically find out about this limitation when they attempt to move to another

store in the franchise chain that provides better career advancement opportunities, hours, pay, or working conditions.

State attorneys general are adopting strategies to aggressively enforce existing state laws in order to prevent the use of franchise no-poaching

agreements. They argue that these agreements violate state and federal antitrust laws that were enacted to prevent anticompetitive practices

such as employers from colluding to keep wages low. Yet corporate franchises often claim that a franchisor and its franchisees should be held to

a different standard since they function as a single entity rather than as competitors.

How are noncompete and no-poach agreements reducing all workers’ wages?

When workers are subject to these sorts of agreements, their ability to bargain for better wages is reduced since they cannot leave a job for a

competitor or to start their own company. While corporations have long required that CEOs and top talent sign agreements not to join rival

firms for a certain period of time, today more than 38 percent of workers across all educational levels—and 35 percent of those without a

2/4

college degree—report signing a noncompete agreement at some point in their lives. Moreover, barring franchises from recruiting the skilled

employees of another franchise can drive down workers’ wages in industries where wages are already very low. For example, fast-food cooks

earn an average hourly wage of $10.39 per hour, or $21,610 annually, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The prevalence of these agreements harms all workers. According to a 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Treasury, living in a state with

strict enforcement of noncompete contracts, compared to one with the most lenient enforcement, is associated with a 5 percent reduction in

pay for a typical 25-year-old worker—and this penalty grows to 10 percent for the typical 50-year-old worker.

Even in California—where courts are not permitted to enforce noncompete agreements—corporations require workers to sign them at rates

similar to those of workers in other states, perhaps because of the agreements’ chilling effects on job mobility and wages. Indeed, to support

robust wage growth, state lawmakers must not only tackle how courts enforce noncomplete laws but also support policies to ensure that

workers are not forced to sign these agreements in the first place.

How are restrictive employment contracts harming entrepreneurship and regional growth?

Allowing workers to move easily between firms can help stimulate the economy as a whole by fostering innovation through information-

sharing; entrepreneurship as workers leave jobs to start new companies; and even regional industry development—since firms can co-locate to

share local talent pools.

Conversely, the negative consequences of limiting job mobility through strict enforcement of noncompete agreements can spread throughout a

state’s economy. For example, studies have found that stricter enforcement of noncompete agreements reduces the number of new firms

entering a state, lowers firm survival rates, reduces startup size, and even delays entrepreneurship among women. Moreover, a 2011 study

reviewing nine years of data found that venture capital funding had stronger positive effects on the number of patents licensed and firm

startups in states with weaker enforcement of noncompete agreements.

Finally, strict enforcement of noncompete contracts can deplete local talent pools by requiring skilled workers to leave their industry of

expertise or relocate out of state to avoid geographic restrictions. For example, a 2011 study of engineers found that about one-third of workers

who signed noncompete agreements left their chosen industry when they changed jobs.

What should states do to better protect workers?

To help raise wages and jump-start entrepreneurship, state policymakers should take the following steps, as detailed in the aforementioned

“Freedom to Leave” report: ban noncompete agreements for most workers, ban franchise no-poaching agreements, and give workers and

enforcement agencies the tools they need to enforce their rights.

1. Ban noncompete contracts for most workers

States should limit noncompete contracts to the small portion of workers with the power to bargain over these agreements. In order to protect

low- and middle-wage workers, states should ban these types of contracts for all workers earning less than 200 percent of the state’s median

annual wage. In addition, lawmakers should prohibit companies that employ at least 50 workers from requiring more than 5 percent of their

workforce to sign such a document. These protections should extend to independent contractors as well.

2. Ban franchise no-poaching agreements

States should ban all no-poaching agreements among franchises. While several state attorneys general, under the authority of existing state

antitrust laws, are taking action against fast-food corporations and other corporate franchisors that require franchisees to sign no-poaching

agreements, clarifying legislation would help to ensure that courts do not rule against workers in the future and that corporations understand

that no-poaching agreements are banned in all forms.

3. Give workers and enforcement agencies tools to enforce their rights

Existing laws place a considerable burden on workers to both know their legal rights and be willing to take on a former employer in court in

order to protect themselves. States should empower workers to stand up for themselves and should bolster enforcement agencies’ ability to

protect workers by requiring companies to disclose all noncompete requirements in job postings and job offers; establishing significant

penalties for use of illegal noncompete and no-poaching agreements; designating and funding enforcement agencies to pursue these sorts of

cases; and allowing workers to sue companies that violate their rights.

How do existing state laws stack up?

Lawmakers in several states—including Maine, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and Washington—are debating policies to protect low- and

middle-wage workers from exploitative noncompete agreements and to ban franchise no-poaching agreements.

To help advance this debate, CAP reviewed existing state statutes governing these kinds of agreements; some—but by no means all—major

cases on the topic; and numerous resources that summarize how state courts have interpreted statutes and existing case law governing

restrictive contractual agreements. The table below represents CAP’s effort to detail how existing state statutes and case law stack up to CAP’s

recommended reforms.

3/4

No state goes far enough under existing laws to protect workers from abusive noncompete and no-poaching agreements. For example, CAP was

unable to find any existing state laws that clarify that franchise no-poaching agreements are illegal. Moreover, most existing state laws that

regulate noncompete agreements focus on how courts should adjudicate legal disputes or protect only a small subset of workers, rather than

banning these sorts of agreements in the first place.

Finally, it is important to note that while a few states have enacted laws that explicitly allow workers who are subject to exploitative agreements

to collect penalties, more general state labor protections—which are not the focus of this table—may help provide workers some recourse. For