Original Paper

Mobile Apps to Support Caregiver-Resident Communication in

Long-Term Care: Systematic Search and Content Analysis

Rozanne Wilson

1

, PhD; Diana Cochrane

1

, MHLP; Alex Mihailidis

2,3,4

, PhD; Jeff Small

1

, PhD

1

School of Audiology and Speech Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

2

Department of Occupational Sciences and Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

3

Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

4

Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada

Corresponding Author:

Rozanne Wilson, PhD

School of Audiology and Speech Sciences

Faculty of Medicine

The University of British Columbia

2177 Wesbrook Mall

Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z3

Canada

Phone: 1 6048225798

Email: r[email protected]

Abstract

Background: In long-term residential care (LTRC), caregivers’ attempts to provide person-centered care can be challenging

when assisting residents living with a communication disorder (eg, aphasia) and/or a language-cultural barrier. Mobile

communication technology, which includes smartphones and tablets and their software apps, offers an innovative solution for

preventing and overcoming communication breakdowns during activities of daily living. There is a need to better understand the

availability, relevance, and stability of commercially available communication apps (cApps) that could support person-centered

care in the LTRC setting.

Objective: This study aimed to (1) systematically identify and evaluate commercially available cApps that could support

person-centered communication (PCC) in LTRC and (2) examine the stability of cApps over 2 years.

Methods: We conducted systematic searches of the Canadian App Store (iPhone Operating System platform) in 2015 and 2017

using predefined search terms. cApps that met the study’s inclusion criteria underwent content review and quality assessment.

Results: Although the 2015 searches identified 519 unique apps, only 27 cApps were eligible for evaluation. The 2015 review

identified 2 augmentative and alternative cApps and 2 translation apps as most appropriate for LTRC. Despite a 205% increase

(from 199 to 607) in the number of augmentative and alternative communication and translation apps assessed for eligibility in

the 2017 review, the top recommended cApps showed suitability for LTRC and marketplace stability.

Conclusions: The recommended existing cApps included some PCC features and demonstrated marketplace longevity. However,

cApps that focus on the inclusion of more PCC features may be better suited for use in LTRC, which warrants future development.

Furthermore, cApp content and quality would improve by including research evidence and experiential knowledge (eg, nurses

and health care aides) to inform app development. cApps offer care staff a tool that could promote social participation and

person-centered care.

International Registered Report Identifier (IRRID): RR2-10.2196/10.2196/17136

(JMIR Aging 2020;3(1):e17136) doi: 10.2196/17136

KEYWORDS

mobile apps; communication barrier; dementia; caregivers; long-term care; patient-centered care

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 1http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Introduction

Background and Rationale

With the growing aging population, there are more people living

with chronic conditions that contribute to physical, sensory

(vision/hearing), and cognitive limitations. The complex health

care needs of older adults living with chronic conditions may

require the services offered in long-term residential care (LTRC)

homes. Most LTRC residents (85%) are functionally dependent

and require care staff assistance (eg, nurse and residential care

aide) while completing activities of daily living (ADLs) [1],

and 25% of residents live with dual sensory loss (hearing and

vision) [2]. Besides physical and sensory limitations, an

estimated 90% of residents live with some cognitive impairment,

with 2 out of 3 residents living with Alzheimer disease and

related dementias (ADRD) [1]. Furthermore, many residents

experience communication difficulties associated with chronic

conditions (eg, sensory loss, dementia, and stroke) and/or a

cultural-language mismatch with care staff that can challenge

interpersonal relationships, and care staffs’ ability to meet

residents’ unique needs [3].

Implementation of a person-centered philosophy of care and

person-centered interventions in LTRC depends on effective

caregiver-resident communication [4]. Person-centered

communication (PCC) involves sharing information and

decisions between care staff and residents, being compassionate

and empowering care provision, and being sensitive to resident

needs, preferences, feelings, and life history [5]. By creating an

environment that uses strategies and tools to enhance PCC,

LTRC care staff can meet residents’ unique needs and foster

interpersonal relationships with the residents [6]. For example,

care staffs’ use of social and task-focused communication

strategies (eg, greet the resident and provide one direction at a

time, respectively) with residents living with dementia support

the successful completion of ADLs [7,8]. Verbal and nonverbal

behaviors (eg, use the resident’s name and make gestures)

contribute to positive communication between residents and

care staff with different linguistic/cultural backgrounds [3].

Although guidelines for supporting person-centered language

in LTRC exist [9], the LTRC setting faces many challenges that

can act as barriers to PCC. One such challenge is language

diversity. In countries that have a history of welcoming

immigrants (eg, Canada, the United States, and Australia), care

staff and residents with diverse linguistic and ethnocultural

backgrounds often comprise LTRC settings [10-14]. For

example, in Canada, most immigrant seniors live in urban areas

(eg, Vancouver and Toronto), with approximately 50% of the

Vancouver senior population being immigrants [15]. Similarly,

it is common to find that English is not the first language of

residential care aides, nor are they born in Canada [16].

Therefore, diversity in the LTRC setting is typical in major

Canadian urban areas, leading to mismatches between care staff

and residents’first language and/or ethnocultural backgrounds.

The shortage of qualified care staff, low wages among

residential care aides, and restrictions on who can provide

specific types of care can lead to a reduction in the time needed

to foster frequent, quality interpersonal interactions with

residents [17]. Finally, resource constraints inherent to the LTRC

setting (eg, time and staffing) can lead to task-focused care

rather than person-focused care and to fewer instances of

caregiver-resident interpersonal interactions [18].

Several traditional approaches to supporting caregiver-resident

communication have been tried in LTRC, including professional

medical translator services for non-English–speaking residents,

communication training programs [19], evidence-based

communication strategies [7,8], employing bilingual care staff

[20], and using augmentative and alternative communication

(AAC) techniques, tools, and strategies (eg, communication

boards and gestures). AAC can be used to address the needs of

residents living with acquired communication disorders (eg,

aphasia and dementia) by supplementing remaining speech

abilities or replacing the voice output when speech is no longer

viable [20,21]. Although the aforementioned supports can be

beneficial, they are often inaccessible to caregivers or residents

because of the limited time available for training and/or

implementation during care routines, limited funding, and

limited on-demand availability.

There is growing recognition of the potential role of technology

in supporting the health care of older adults [21], with a focus

on person-centered care [22-25]. In particular, the use of mobile

communication technology (MCT), which includes mobile

devices such as tablets and smartphones, along with their

software apps, offers an innovative approach for supporting

person-centered care. There are several advantages to using

MCT in health care settings: (1) the devices are accessible,

portable, small, lightweight, rechargeable, relatively easy to

use, and inexpensive, have advanced features (eg, camera and

sound recording), and have enough computing power to support

web searching; (2) a variety of apps are available in the major

app marketplaces; and (3) a wireless connection offers

continuous, simultaneous, and interactive communication from

any location [26].

In a short period, the availably of mobile apps has increased

exponentially across the 2 largest app marketplaces: Google

Play (Android platform) and the App Store (iPhone Operating

System [iOS] platform). For example, in 2014, there were an

estimated 2.6 million apps across the 2 marketplaces [27] and,

by 2019, this number climbed to 5.5 million apps (111%

increase) [28]. In addition to the convenience and commonplace

of MCT, the appeal of using apps in health care may be because

of the range of available built-in features that can support

individuals’needs, preferences, and abilities (ie, person-centered

care), including larger touch screen interfaces with tactile

feedback, motion sensors, voice recognition, cameras, video

recorders, and multimedia content (eg, images, sound, and text)

[29]. App content can also be customized to support the unique

needs of a target population. For example, apps designed for

older populations can incorporate larger text and zoom

capability; allow for preferred vocabulary, photos, and text; and

have the options to save voice and video recordings. Thus,

MCTs are useful tools for health care professionals and can

support target populations with specific needs, such as those

living with ADRD [29-32]. However, more information is

needed to determine how these technologies could address

specific challenges that caregivers encounter with target

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 2http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

populations (eg, dementia [33]) living in LTRC. Furthermore,

given the rapidly changing landscape of the app marketplace

(eg, new, updated, and removed apps), it is important to better

understand the stability of apps in the marketplace. The

longevity of apps has important implications in the LTRC

context. For example, for training care staff to use an app that

is subsequently removed from the marketplace would be a waste

of financial resources. The first step to examining the use of

MCT in the LTRC setting is to better understand the suitability

of currently available commercial apps for supporting

communication in the LTRC context and the stability of these

apps over time.

Using mobile devices, along with AAC apps and language

translation apps, collectively referred to as communication apps

(cApps) in this paper, may offer an innovative approach to

enhancing PCC in LTRC. In particular, cApps have the potential

to support care staff and residents living with acquired

neurogenic communication disorders [34] and/or

linguistic/ethnocultural barriers [14] during daily activities. For

example, cApps could be used as follows: (1) support residents’

participation in their own care; (2) help identify, save, and share

residents’ individualized needs and preferences during care

routines; (3) personalize activities and social engagement; (4)

support information sharing between care staff and residents

during daily care; (5) prevent and/or overcome communication

breakdowns during ADLs by meeting residents’unique needs;

and (6) promote social participation. However, to date, there

appears to be no evidence about the availability of cApps that

could support communication between care staff and LTRC

residents during daily care routines. Recently, regulations and

guidelines for the development and use of technologies in health

care have been developed [35]. However, the existing

commercially available apps were likely developed with limited

regulatory oversight, resulting in little evidence for the validity

and reliability of app content and questionable quality [36].

Therefore, we need to better understand the availability and the

content quality of currently available cApps. This information

will help to determine which cApp could be suitable for

supporting caregiver-resident communication in LTRC.

Research Aims

This app review aimed to systematically identify and examine

existing commercially available AAC and translation apps (ie,

cApps) that care staff could access to support PCC with LTRC

residents during daily activities. The specific objectives of this

study were as follows:

1.

To systematically identify commercially available apps

designed for adults living with a communication impairment

(AAC apps) and/or experiencing a language barrier

(translation apps).

2.

To assess cApp content (description of app characteristics

and PCC features), with a focus on suitability and relevance

to the LTRC setting.

3.

To assess the quality of eligible cApps, with a focus on

functionality, ease of use, and customization.

4.

To recommend the top existing cApps best suited for

supporting caregiver-resident communication during ADLs.

5.

To replicate the review to better understand how a rapidly

evolving app marketplace may impact the suitability and

longevity of cApps in the LTRC setting over a 2-year

period.

Methods

Identification Phase

Search Strategy

The systematic search for cApps in the Canadian marketplace

was conducted between April and June 2015 and involved 5

steps: (1) internet search for AAC and translation apps using

the Google search engine; (2) consultation with a

speech-language pathologist (SLP) with expertise and

knowledge in using AAC apps with adults living with a

communication impairment (ie, clinical expert) to identify AAC

apps recommended for use by adults living with a

communication impairment; (3) scientific literature search

focused on the use of mobile apps to support communication

in the LTRC setting; (4) preliminary search of the official

Canadian app stores of the 2 major operating systems (Android

and iOS): Google Play and App Store; and (5) comprehensive

search of the Canadian App Store (iOS platform; Figure 1).

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 3http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Figure 1. Summary of the steps involved in the identification phase of the communication app reviews. Note that a consultation with a clinical expert

and a preliminary search were not conducted for the 2017 review. iOS: iPhone Operating System.

Initial Identification

To gain a better understanding of the scope of the relevant and/or

recommended AAC and translation apps available in the app

marketplace, a Google search, a consultation with a clinical

expert, a review of the scientific literature, and preliminary

marketplace searches were completed. The Google search was

conducted to help flag popular AAC and translation apps that

should appear in the marketplace searches. The Google searches

were done using a Google Chrome web browser by a single

author (RW) on the same PC laptop computer (Windows 8;

logged into a Google account) and involved separate searches

for AAC apps and translation apps (Table 1). Google algorithms

place the most relevant search results on the first result page

and the majority of searchers stay on the first page [37]. To

ensure comprehensiveness, the first 3 pages of the internet

search results (50 results per page) were screened for links to

specific apps and for links to websites that recommended apps

useful for older adults living with a communication impairment

or language barrier. Next, a consultation meeting with a clinical

expert took place. The SLP shared a detailed spreadsheet of

AAC apps that she used with her clients and identified which

AAC apps would be appropriate for adults living with a

communication impairment in the LTRC setting. The scientific

literature search was conducted to identify research reporting

on the use of MCT to address the communication needs of

vulnerable residents in LTRC. Searches were conducted in

MEDLINE, AgeLine, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and

Allied Health Literature academic electronic databases in April

2015 and in February 2016 (RW). Broad search terms were

used to capture subdomains of communication

challenges/barriers, including language differences or aphasia.

Free vocabulary (keywords) and controlled vocabulary (eg,

Medical Subject Heading terms) were used for the combined

concepts (Table 1). No date restrictions were applied to the

searches and search results were limited to peer-reviewed

academic literature and the English language. No relevant results

were found in the literature searches. Finally, 2 reviewers

(authors RW and DC) performed a preliminary search of both

the App Store (iOS) and Google Play (Android) on a desktop

computer to assess which marketplace appeared to have the

highest inventory of AAC and translation apps. On the basis of

information gathered from the Google search, the clinical expert,

and the preliminary search of both market stores, the App Store

(iOS) had the highest inventory of AAC and translation apps.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 4http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Table 1. Search terms used in Google Chrome and electronic databases.

Search terms (controlled and free vocabulary)Search location

Google Chrome

Function

augmentative and alternative communication apps for smartphones or tablets

AAC

a

AAC apps for smartphones or tablet

adult augmentative and alternative communication apps for smartphones or tablets

adult AAC apps for smartphones or tablets

AAC apps for smartphones or tablets for frail elderly

AAC apps for smartphones or tablets for long-term care residents

AAC apps for smartphones or tablets in hospital for patients

communication app for adult patients

translation apps for smartphones or tabletsTranslation

translation apps for smartphones or tablets

medical and health care translation apps

Electronic databases

Population

older adult*, OR aging OR ageing, OR aged OR, senior*, OR elder*, OR frail elder*, OR dementia,

OR nursing home resident*

Older adults

AND

caregiver*, OR nurse*, OR nurse aide, OR health care aide*Caregivers

AND

communication, OR communication barrier, OR communication aids for disabled, OR assistive technol-

ogy, OR alternative and augmentative communication, OR AAC, OR communication disorder, OR

communication impairment

Communication barrier

AND

Intervention

smartphone*, OR computer*-handheld, OR tablet computer*, OR cell* phone, OR portable computer*,

OR mobile app*, OR software app*, OR computer software, OR app*

Mobile communication technology

AND

Outcome

Person-centred care, OR Personhood, OR person-centred communication, OR communication strategies,

OR person-centredness

Person-centered communication

AND

Setting

nursing home, OR long term care, OR institutional care, OR nursing home patient*, OR nurse-patient

relations, OR nurse attitude*

Long-term residential care

a

AAC: augmentative alternative communication.

App Store Search

For this study, the identification of AAC and translation apps

that support interpersonal communication between LTRC

residents and care staff during ADLs focused on a

comprehensive search of the Canadian iOS marketplace: App

Store for desktop computer searches and for mobile device

searches (tablet and smartphone). AAC apps were searched in

the medical, communication, education, lifestyle, and health

and fitness categories of the App Store. Several keyword

searches were conducted, with the keywords “AAC,” “AAC

communication,” “adult communication apps,” and

“communication disability” returning most of the search results.

The translation apps were searched in the medical education,

health and fitness, reference, productivity, utilities, and business

categories, using the keywords “translation apps,” “translate

apps,” “medical,” and/or “health care translator apps,” and

“multi-language translate.” To verify search results, 2 authors

(RW and DC) performed independent searches for AAC apps

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 5http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

and for translation apps in the App Store, producing similar

results.

Selection Phase

The iOS marketplace search results were exported to Microsoft

Excel, and a single reviewer (DC) removed duplicates and

screened the remaining apps (names/titles) for being foreign

(ie, non-English title) and/or unrelated to interpersonal

communication (eg, dictionary app). If the app’s name did not

clearly indicate that it was unrelated to communication or was

foreign, the app was included for eligibility screening. For apps

available in multiple versions, the complete version (ie, fully

featured, no limitations, and no in-app purchase required) was

included for eligibility screening and the less complete apps

were marked as duplicates. In the case of apps with multiple

versions that were identical except for the voice setting (male

or female), the adult female voice version was selected and the

other version was marked as a duplicate. This decision was

made because LTRC care staff are typically female [16].

Following the initial screening, the study’s inclusion and

exclusion criteria were applied (Textboxes 1 and 2). Two

reviewers (authors RW and DC) independently applied the

inclusion/exclusion criteria to approximately 20.0% of the apps

(AAC: 36/181; translation: 4/18) by reviewing the App Store

description. Following acceptable agreement, any disagreements

were discussed, with final inclusion/exclusion decisions based

on consensus. If needed, a third reviewer (JS) would assist in

the inclusion/exclusion decision. A single reviewer (DC) applied

the inclusion/exclusion criteria to all remaining apps. AAC apps

and translation apps that met all the inclusion criteria, and none

of the exclusion criteria, were included for metadata extraction,

feature coding, and quality assessment.

Textbox 1. Inclusion criteria for communication apps study eligibility.

•

Communication function: augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

•

The app’s primary function is AAC for adults

•

Communication was included as a keyword or in the text description of the app

•

Can communicate basic needs (eg, feelings, emotions, preferences, and activities)

•

Available in English

•

Can support communication between a care provider and a patient in a health care setting

•

Can be customized to support individual needs and preferences

•

Includes all visual and auditory feedback functions (ie, images, text, and speech/sound)

•

Communication function: translation apps

•

The app’s primary function is language translation

•

Available in multiple languages

•

Incudes text-to-speech, speech-to-text, and speech-to-speech translation functions

•

Could be used over the web and offline (eg, download language libraries for offline use)

•

Option to save words/common phrases to a word bank on a tablet device

•

Customization option (eg, save favorite words for quick access)

Textbox 2. Exclusion criteria for communication apps study eligibility.

•

Communication function: augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

•

Requires substantial changes/modifications to use in the long-term residential care setting during the completion of activities of daily living (eg,

need to import most images, create text and speech, add/delete built-in features)

•

No longer available in the Canadian App Store

•

Images are not adult appropriate (eg, child cartoon characters)

•

Unrelated to communication with adults living with a communication difficulty

•

Unrelated to communicating basic needs

•

Does not include all visual and auditory feedback functions (ie, image, text, and speech/sound)

•

Communication function: translation apps

•

Does not support human-language translation

•

Converting English to a single language was the only translation option

•

Text-to-text was the only available feature of the app

•

No longer available in the Canadian App Store

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 6http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Evaluation Phase

Data Extraction for Content Analysis

Using a tablet device, a single author (DC) extracted the

metadata content for all eligible AAC and translation apps from

information provided in the Canadian App Store descriptions.

In addition, if available, information was extracted from the

developer’s website and/or through reviewing web-based

training modules or videos demonstrating the app. For content

analysis, the authors (RW and JS) developed a detailed feature

coding scheme to guide data collection for each cApp. For each

cApp, extracted descriptive data were entered into a standard

Microsoft Excel worksheet that contained the following

metadata categories: (1) general description: search date, app

name, app function, screenshot, keywords, and brief app

description; (2) technical information: marketplace/platform,

category, language, last software update, cost, and marketplace

longevity; (3) target user: general, living with a communication

disability, living with aphasia, and other; and (4) other: upgrade

with purchase, offline ability, technical support, translation

function, and indication of informed design (ie, SLP, clinician,

end user, and/or research was used to inform the development

of the app).

On the basis of the extracted metadata, a set of secondary

selection features were compiled for the AAC apps and for

translation apps (Textbox 3). These secondary selection features

were considered to be ideal characteristics of an app used in the

LTRC setting (eg, a low-cost app with technical support would

increase access and offer technical assistance to care staff) and

were strongly considered during the identification of the cApps

best suited to support PCC during ADLs in the LTRC setting.

Evaluated cApps were identified as having a secondary selection

feature by indicating yes or no for the presence or absence of a

feature.

Textbox 3. Secondary selection features.

•

Communication function: augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

•

Low cost (app <Can $100 [US $75.5])

•

In the marketplace for at least two years (longevity/stability)

•

Web-based and offline capabilities

•

Technical support (email, phone, and web)

•

Includes a translation function

•

No cost/low cost for additional languages

•

Communication function: translation apps

•

Low cost (app <Can $100 [US $75.5])

•

In the marketplace for at least two years (longevity/stability)

•

Web-based and offline capabilities

•

Technical support (email, phone, and web)

•

No cost/low cost for additional languages

In addition, during the prepurchase review of the eligible cApps,

data were collected on built-in and customizable features that

support resident needs, preference, and feeling, as well as

sharing of information between residents and care staff (eg,

supports vision loss, option to add personal pictures, and

two-way communication). All built-in and custom features were

coded as being present (yes) or absent (no) in each app. The

detailed feature coding scheme aided in the identification of

cApps that included the highest number of PCC features (ie,

built-in and customizable) relevant to the LTRC setting.

Quality Assessment

For both the AAC and translation apps, quality assessment rating

criteria (Table 2) were derived from 3 dimensions of the Mobile

Application Rating Scale [38] that were deemed relevant to this

study: engagement (customization), functionality (ease of use),

and aesthetics (graphic presentation and visual appeal). Each

of the criteria was rated on a scale of 0 to 2 (0=poor, 1=fair,

2=good or 0=not at all easy, 1=somewhat easy, 2=easy). cApp

quality assessment was conducted in 2 steps: a prepurchase

quality assessment and a final quality assessment of purchased

cApps. During the prepurchase quality assessment step, 3

reviewers (authors RW, DC, and JS) independently applied the

quality assessment rating criteria to the cApps by reviewing the

store description, product tutorials/videos, or web-based videos

(eg, YouTube) or by downloading freely available cApps.

During the prepurchase evaluation, the initial quality assessment

did not include ratings on sound quality (AAC) and translation

accuracy because this information was typically unavailable

without purchasing the app. All apps were assessed in

alphabetical order. After ratings were complete, each reviewer

judged whether the app was suitable for supporting

communication in LTRC (yes/no/possible), followed by a

decision to purchase/download the app for further evaluation

(yes/no/maybe).

Following an independent review, the 3 authors convened to

comparatively discuss the apps’ initial quality assessment ratings

and the apps’ suitability for communication in LTRC.

Collectively, the reviewers generated a shortlist of cApps that

would be purchased/downloaded to undergo a final quality

assessment. Although the cApp ratings were deemed important

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 7http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

to the purchase/download decision, cApps that included features

appropriate for caregiver-resident communication in LTRC, as

well as cApps with customization abilities, were given a higher

degree of consideration in the purchase decision. In addition,

if there were disagreements between reviewers’ decision to

purchase/download a cApp, the undecided cApp was included

for further evaluation. Therefore, the approach taken to generate

the shortlist could result in the purchase/download of a cApp

with a lower median initial quality assessment rating, as well

as the decision not to purchase/download a cApp with a higher

initial quality assessment rating. Two reviewers (authors DC

and JS) independently documented their experience using each

shortlisted cApp and completed the final quality assessment for

the AAC and translation apps. All shortlisted apps were

downloaded to an iPad Mini 4 device with an iOS 9 operating

system and a 7.9″ display for a direct user experience.

Table 2. Quality assessment rating categories for communication apps.

Categories

b,c,d

Communication function

a

Augmentative and alternative communication

•

Sound quality: How intelligible is the audio output?

•

Graphic presentation: What is the visual interface quality (image resolution detail

[pixels] and image clarity)?

•

Visual interface presentation: What is the overall appeal of the app look (ie, color

display, patterns, lines, scale, image/text type, image/text appropriateness, and dis-

play options)?

•

Ease of use: Overall, how easy is it to use the software interface (ie, app is intuitive

to learn and requires minimal explanation to use; instructions are clear; simple,

straightforward display; quick access to common features and commands; well-or-

ganized [layout] and easy to navigate)?

•

Customization: How easy is it to customize the app?

Translation

•

Sound quality

•

Graphic presentation

•

Visual interface presentation

•

Ease of use

•

Translation accuracy: How accurate are the translated words/text

a

The maximum total score for the final quality assessment ratings=10 (augmentative and alternative communication and translation apps).

b

Sound quality, graphic presentation, visual interface presentation, and translation accuracy were rated on a scale of 0 to 2 (0=poor, 1=fair, 2=good).

c

Ease of use and customization were rated on a scale of 0 to 2 (0=not at all easy, 1=somewhat easy, 2=easy).

d

Sound quality and translation accuracy were only applied in the final quality assessment of purchased/downloaded cApps.

Final Recommendation Phase

Following the independent assessment of all cApps, 3 reviewers

(RW, DC, and JS) reconvened to discuss their experience with

each app. The final selection of the most suitable cApps in the

AAC category and in the language translation category was

determined by research team consensus and was based on the

combined findings of a three-stage comparative process

involving the review of the extracted feature data, the initial

quality assessment of eligible cApps, the user experience, and

the final quality assessment of the purchased cApps.

Replication Review

The identification phase of the replication review took place in

October 2017, and the evaluation phase was completed in July

2018. Apart from a consultation with a clinical expert, the

identification phase involved the same methodological approach

as the original 2015 review. Three trained research assistants

completed the Google search, the comprehensive iOS

marketplace search, and the initial screening (duplicates, foreign,

and unrelated), while 1 author (RW) conducted the scientific

literature search in October 2017. For the 2017 systematic app

review, all search terms used in the Google search, in the

comprehensive app store search, and in the literature search

were identical to the terms used in the 2015 search (Table 1).

As with the 2015 review, Google searches were performed using

the Google Chrome web browser and involved separate searches

for AAC apps and translation apps. A single research assistant

performed all AAC internet searches on the same PC laptop

computer, and a single research assistant performed all

translation searches on the same PC laptop computer. The

literature search returned no relevant results. To replicate the

2015 review, only the Canadian App Store (iOS platform) was

searched during the 2017 review.

Two reviewers (RW and DC) completed the selection,

evaluation, and recommendation phases of the 2017 replication

review. An agreement check was performed for eligibility

assessment, whereby 2 reviewers independently assessed

approximately 20.0% of the apps (AAC: 61/306; translation:

60/300). Following acceptable agreement, any disagreements

were discussed, with final inclusion/exclusion decisions based

on consensus and, if needed, a third reviewer (JS). A single

reviewer (DC) applied the inclusion/exclusion criteria to all

remaining apps. There were two instances in which the

procedure for the 2017 replication review differed from the

2015 review. First, multiple versions of the same app (eg, lite

[free] and pro [cost]) were treated as unique apps in the 2017

replication review because each version included different

features and was anticipated to have varying quality levels.

Therefore, a lite version may qualify for evaluation, whereas

the pro version may not because of the higher cost. Apps that

underwent software updates since the 2015 review were still

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 8http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

considered the same version of the app. Second, secondary

selection features were applied to eligible cApps before the

evaluation phase of the 2017 replication review to further narrow

the pool of cApps that underwent quality assessment. Only

cApps with all secondary selection features were evaluated in

the 2017 review. As with the 2015 review, all quality assessment

ratings were completed using an iPad mini 4 (iOS 12.2 operating

system and 7.9″ display).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics are used to summarize cApp

characteristics, PCC features, and quality assessment ratings.

To quantify change between the 2015 review and the 2017

replication review, the number and/or proportional

increase/decreases are reported, with numbers/percentages

presented from 2015 to 2017 (ie, from X to Y).

Results

Original Review

The 2015 App Store searches identified a total of 752 cApps

(AAC=614; translation=138). The search terms AAC, AAC

communication, and communication disability accounted for

90.4% (555/614) of all identified AAC apps. The search terms

translation apps and translate apps accounted for 72.5%

(100/138) of all translation apps identified in the initial search.

After screening for duplicates, foreign, and unrelated apps, a

total of 181 unique AAC apps and a total of 18 unique

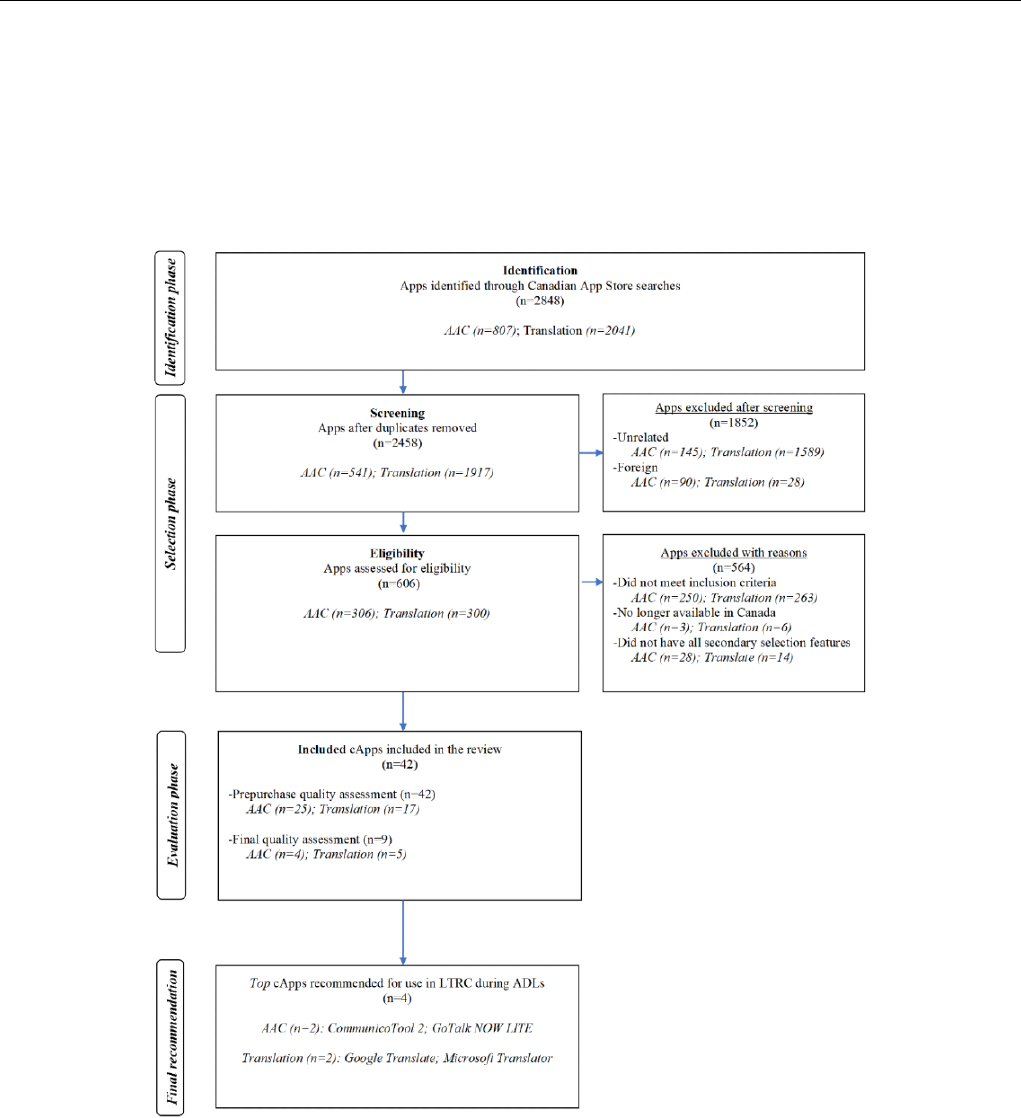

translation apps were identified. Figure 2 displays the 2015

search results, which was guided by the Preferred Reporting

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram

template [39]. After applying this study’s inclusion/exclusion

criteria to the identified apps, 27 cApps were included in the

study (Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 2. Flow diagram summarizing the results of the identification, selection, evaluation, and final recommendation phases involved in the 2015

communication app review. The presentation of results was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow

diagram template AAC: augmentative and alternative communication; ADLs: activities of daily living; LTRC: long-term residential care.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 9http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Table 3. List of communication apps evaluated in the 2015 review.

AppsCategory

Augmentative and alternative communication (n=23)

•

Alexicom Elements Adult Home (Female)

a

•

App2Speak

a,b

•

AutisMate365

c

•

ChatAble

a

•

CommunicAide

•

CommunicoTool Adult

a,d

•

Compass (DynaVox)

•

Conversation Coach

a,b,d

•

Easy Speak—AAC

c

•

Functional Communication System

c

•

GoTalk NOW

a,d

•

iAssist Communicator

c

•

iCommunicate

a

•

image2talkb

b,e

•

MyTalkTools

a,d

•

PictureCanTalk

a,c

•

Proloquo2Go

a

•

Smart_AAC (med)

d

•

Sono Flex

a,d

•

SoundingBoard

•

Talkforme

c

•

TalkTablet

a,d

•

TouchChat AAC

Translation (n=4)

•

Google Translate

a,b

•

iTranslate

a,d

•

SayHi Translate

c

•

TableTop Translator

a,b

a

Indicates that this app met study eligibility in the 2015 review and in the 2017 review.

b

Indicates that the same version of the app was evaluated in the 2015 and in the 2017 reviews.

c

Indicates that this app was no longer available in the marketplace during the 2017 review.

d

Indicates that a different version of the same app was evaluated in the 2017 review (eg, 2015: CommunicoTool Adult; 2017 CommunicoTool 2).

e

For cApps with multiple versions, if a version of the cApp was evaluated in both the 2015 and in the 2017 review (eg, GoTalk NOW LITE and GoTalk

Start different versions [ie, fewer features] of GoTalk NOW), it was not categorized as a newly evaluated cApp.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 10http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Table 4. List of communication apps evaluated in the 2017 replication review.

AppsCategory

Augmentative and alternative communication (n=25)

a

•

App2Speak

•

CommunicoTool 2

•

Conversation Coach

•

Conversation Coach Lite

b

•

CoughDrop

c

•

Gabby

c

•

GoTalk NOW LITE

b

•

GoTalk Start

b

•

image2talk

•

iMyVoice Lite

b,c

•

iMyVoice Symbolstix

c

•

iSpeakUp

c

•

iSpeakUp Free

b,c

•

LetMeTalk

c

•

Mighty AAC

c

•

MyTalkTools Mobile Lite

•

SmallTalk Aphasia—Female

c

•

Sono Flex Lite

b

•

TAlkTablet CA AAC/Speech for aphasia

d

•

TalkTablet LITE—Eval Version

b

•

TalkTablet US AAC/Speech for aphasia

d

•

urVoice AAC—Text to speech with type and talk

c

•

Visual Express

c

•

Visual Talker

c

•

Voice4u AAC

c

Translation (n=17)

•

Google Translate

•

Instant Translator—Converse

c

•

iTranslate Translator

c

•

iTranslator—Speech translation

c

•

iVoice

c

•

LINGOPAL 44

c

•

Microsoft Translator

c

•

Multi Translate Voice

c

•

Online—Translator.com

c

•

Voice Translator Reverso

c

•

Speak & Translate—Translator

c

•

TableTop Translator

•

The Interpreter—translator

c

•

Translator with Speech HD

c

•

Translator—Speak & Translate

c

•

TravTalk—Talking & Recording Phrasebook

c

•

Yandex.Translate: 94 languages

c

a

For cApps with multiple versions, if a version of the cApp was evaluated in both the 2015 and in the 2017 review (eg, GoTalk NOW LITE and GoTalk

Start different versions [ie, fewer features] of GoTalk NOW), it was not categorized as a newly evaluated cApp.

b

cApps that were newly evaluated in the 2017 review.

c

A free or low-cost version of a fully featured app that is available for a higher cost.

d

A different version of the same app.

Content Analysis

Extracted metadata for the evaluated cApps indicated that 91%

(21/23) of AAC apps were only available for the iOS platform,

while 50% (2/4) of translation apps were available for both the

iOS and the Android marketplaces. The majority of AAC apps

(18/23, 78%) were categorized as education apps and most

likely included one or more of the following keywords: AAC

(18/23, 78%), communication disability (10/23, 43%), basic

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 11http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

needs (4/23, 17%), or daily living (4/23, 17%). Half of the

translation apps (2/4) were categorized as business apps and all

were labelled with the keyword translate. The majority of AAC

apps (18/23, 78%) identified people living with a communication

disability as the target user, whereas all translation apps (n=4)

were designed for a general audience. Most AAC apps were

available in English only (17/23, 74%), and the last software

update was within 1 year (17/23, 74%). All translation apps’

software was updated in the current year (ie, 2015). Some of

the free AAC apps were limited versions of an app that could

be upgraded with a purchase (eg, CommunicAide (free) and

CommunicAide Pro, Can $99.99 [US $75.5]), and the majority

(14/23, 61%) of AAC apps provided no indication of informed

design. Only 17% (4/23) of the AAC App Store description

and/or the developer’s webpage indicated the inclusion of an

SLP in the development of the app (App2Speak, Chatable,

CommunicAide Free, and CommunicoTool Adult), while 9%

(2/23) indicated research was used to inform the content

(Compass [DynaVox] and Proloquo2Go), and 13% (3/23)

included the end user (Talkforme, image2talk, and

MyTalkTools).

Most of the AAC apps cost Can $100 (US $75.5) or less (17/23,

75%), were available in the marketplace for 2 years or more

(18/23, 78%), and provided technical support (22/23, 96%;

Table 5). All translation apps cost less than Can $25 (US $18.9),

3 out of the 4 apps provided technical support, and the majority

(3/4, 75%) were available in the marketplace for 2 years or

more. Although about half of the AAC apps indicated some

offline functionality, only 1 translation app (Google Translate)

had limited offline functionality. Although no AAC app included

all secondary selection features, 83% (19/23) of the AAC apps

contained three or more of these features. GoTalk NOW,

SoundingBoard, AutisMate365, Conversation Coach, Functional

Communication System, and MyTalkTools contained the most

of these features. Except for online and offline capabilities, 75%

(3/4) of the translation apps included each of the secondary

selection features.

Appraisal of PCC features indicated that 3 AAC apps (GoTalk

NOW, Talkforme, and MyTalkTools) contained 11 or more of

the built-in and custom features. Only 1 AAC app contained all

5 custom features (GoTalk NOW) and 1 AAC app included

nearly all the built-in features (Talkforme). One translation app

contained 86% (6/7) of all applicable features (Google

Translate). Almost half of the AAC apps included 50% to 74%

of the features that were deemed to support PCC, and 75% (3/4)

of the translation apps contained some of the features (Table

6). Although all AAC apps indicated that they supported hearing

loss (eg, speech rate adjustment, voice customization, and

speech-to-text function), only 43% (10/23) supported vision

loss (eg, high-resolution images, zoom function, and large

images) and two-way communication (ie,

conversation/interpersonal). All translation apps supported

hearing and vision loss. Only 3 AAC apps included a built-in

translation function (Talkforme, MyTalkTools, and TouchChat

AAC). The majority of AAC apps included multiple display

modes, natural voice output, and text-to-speech output. The

ability to add personal photos/images and the option to add

personal voice recordings were the most common custom

features among the AAC apps, and all translation apps included

vocabulary customization.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 12http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Table 5. Secondary selection feature summary of the evaluated communication apps (cApps; note: as the percentages were rounded, some categories

may not add up to 100%.

Change over time, (%)

d

2017 replication review2015 reviewSecondary feature

TranslationAACTranslation (n=17)

c

, n (%)AAC (n=25)

b

, n (%)Translation (n=4), n (%)AAC

a

(n=23), n (%)

Cost in Can $ (low cost: app <Can $100 [US $75.5])

7613515 (88)10 (40)2 (50)4 (17)Free

−761672 (12)6 (24)2 (50)2 (9)<$25 (US $18.9)

0−470 (0)4 (16)0 (0)7 (30)$25-$49 (US

$18.9-US $37)

0−1000 (0)0 (0)0 (0)1 (4)$50-$75 (US

$18.9-US $37.8)

0−690 (0)1 (4)0 (0)3 (13)$75-$100 (US

$37.8-US $75.5)

0−380 (0)4 (16)0 (0)6 (26)>$100 (US

$75.5)

1−313 (76)19 (76)3 (75)18 (78)In the marketplace for

at least two years

(longevity/stability)

e

3007517 (100)25 (100)1 (25)13 (57)Web and offline capa-

bilities

f

25416 (94)25 (100)3 (75)22 (96)Technical support

(email, phone, web)

N/A−69N/A1 (4)

N/A

g

3 (13)Includes a translation

function

0N/A17 (100)N/A4 (100)N/ANo cost/low cost for

additional languages

a

AAC: augmentative and alternative communication.

b

In total, 11 AAC apps were evaluated in both the 2015 review and in the 2017 review.

c

In total, 3 translation apps were evaluated in the 2015 review and in the 2017 review.

d

A negative percentage indicates a decrease in the percentage of cApps with the secondary feature over the 2-year period.

e

The app copyright date was used to document marketplace longevity. In the absence of a copyright date, the oldest software update date was used.

f

Functions/features available offline may be limited compared with the features available during app use over the web.

g

Not applicable.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 13http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Table 6. Summary of features that support person-centered communication (PCC) in the evaluated communication apps (cApps; this table describes

PCC features found in the evaluated cApps during the 2015 review and in the 2017 replication review, as well as evaluates the percentage of cApps

with a PCC feature between the 2015 and 2017 reviews. Data were extracted from the Canadian App Store description and during the prepurchase

review of the cApps. Feature categories were not mutually exclusive; therefore, 1 app could have several built-in features and/or custom features).

Change over time, (%)

b

2017 review2015 reviewPerson-centered communication features

TranslationAACTranslation

(n=17)

AAC

(n=25), n

(%)

Translation (n=4),

n (%)

AAC

a

(n=23), n

(%)

Built-in features (n=9)

6−269 (53)8 (32)2 (50)10 (43)

Supports vision loss

c

−6016 (94)25 (100)4 (100)23 (100)

Supports hearing loss

d

−351511 (65)25 (100)4 (100)20 (87)

Multiple display representations

e

−68−311 (24)17 (68)3 (75)16 (70)

Natural sounding voice output

f

N/A4N/A25 (100)

N/A

g

22 (96)Text-to-speech function

N/A−56N/A1 (4)N/A2 (9)Speech-to-speech function

N/A−69N/A1 (4)N/A3 (13)Translation function

N/A26N/A11 (44)N/A8 (35)Available in multiple languages

−45−357 (41)7 (28)3 (75)10 (43)

Supports two-way communication

h

Custom features (n=5)

−2912712 (71)17 (68)4 (100)7 (30)

Can customize vocabulary

i

−28−33 (18)19 (76)1 (25)18 (78)Can add/save personalized photos/images

N/A−9N/A8 (32)N/A8 (35)Can to add/save personalized text

N/A−8N/A15 (60)N/A15 (65)Option to add/save personal voice record-

ings

N/A41N/A6 (24)N/A4 (17)Can add/save personalized videos

Total number of features

j

N/AN/A0 (0)0 (0)0 (0)0 (0)

cApps

k

with all applicable features

−28−383 (18)2 (8)1 (25)3 (13)cApps with most features (approximately

75% or more)

−3708 (47)12 (48)3 (75)11 (48)cApps with some features (approximately

50%-74%)

N/A136 (35)11 (44)0 (0)9 (39)cApps with few features (less than 50%)

a

AAC: augmentative and alternative communication.

b

Percent change calculation: ([percentage of 2017 apps with the feature−percentage of 2015 apps with the feature]/percent of 2015 apps with the

feature)*100. A negative percentage indicates a decrease in the percentage of cApps with the person-centered communication feature over the 2-year

period.

c

Features that support vision loss include high-resolution images, zoom function, and large pictures/text.

d

Features that support hearing loss include volume control, earbud option, speech rate adjustment, voice customizations, and speech-to-text function.

e

Multiple display representations indicate that the app includes two or more features: text, handwriting option, speech input, camera/photo pictures,

images, symbols, and video.

f

Information about voice output was not available for 4 AAC apps during the data extraction phase.

g

Not applicable.

h

Supports two-way communication means that the app could be used for caregiver-resident task-focused and/or interpersonal-focused communication

(eg, conversation view).

i

Option to customize vocabulary includes saving frequently used words/phrases in the following manner: pages, favorite lists, history, and add personalized

vocabulary.

j

A total of 14 person-centered features applied to AAC apps (built-in=9; custom=5). A total of 7 person-centered features were applicable for translation

apps (built-in=5; custom=2).

k

cApp: communication app.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 14http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Quality Assessment

Initial quality assessment of the eligible cApps indicated that 7

AAC apps were highly rated: Alexicom Elements Adult (median

8), TalkforMe (median 8), App2Speak (median 7),

CommunicAide (median 7), CommunicoTool Adult (median 6),

Functional Communication System (median 6), and GoTalk

NOW (median 6). After considering secondary selection features

and the initial quality assessment during a research team

discussion, 9 AAC apps and 3 translations apps were shortlisted

for purchase/download (Table 7). Following completion of the

final quality assessment ratings for each of the shortlisted cApps,

CommunicoToolAdult and GoTalkNOW had the highest median

ratings for AAC apps (Table 7). The research team reconvened

for a final comparative review of the cApps. On the basis of

consensus decisions, the top recommended cApps were

finalized: CommunicoTool Adult, GoTalk NOW, Google

Translate, and TableTop Translator (Multimedia Appendix 1).

Although TableTop Translator and SayHi shared the same

developer, the researchers selected TableTopTranslator because

this app included more language options and the screen display

supported two-way communication.

Table 7. Communication apps downloaded for final quality assessment ratings (the final quality assessment rating is based on the median rating of 2

reviewers. The maximum total rating score for cApps apps was 10).

Quality assessment ratings

cApp communication function and name

a

2017 search (n=8)2015 search (n=12)

Augmentative and alternative communication

8.56.5App2Speak

8.5

b,c

9

b

CommunicoTool Adult

N/A

d

5Functional Communication System

8

b,e

7.5

b

GoTalk NOW

N/A0iAssist Communicator

N/A3iCommunicate

N/A0image2talk

N/A1SoundingBoard

N/A1.5Talkforme

Translation

9.5

b

8

b

Google Translate

9.5

b

N/AiVoice Translator

10

b

N/AMicrosoft Translator

8N/AOnline-Translator.com

8.5

8

b

TableTop Translator

f

N/A8SayHi Translate

a

Communication apps (cApps) are listed in alphabetical order.

b

Top recommended cApps for use in long-term residential care to support communication between residents and caregivers.

c

CommunicoTool 2 was evaluated in the 2017 review.

d

Not applicable.

e

GoTalk NOW LITE was evaluated during the 2017 review.

f

TableTop Translator and SayHi shared the same developer.

Replication Review

Content Analysis

Following a comprehensive search of the App Store and the

removal of duplicates, foreign, and unrelated apps, a total of

607 apps were screened for study eligibility (Figure 3). A total

of 93 apps met the study’s inclusion criteria. After applying the

secondary selection features to further narrow down the pool

of cApps, a total of 42 apps were evaluated (AAC: n=25;

translation: n=17; Tables 3 and 4). In all, 36% (9/25) of the

evaluated AAC apps were a different version of the same app

(eg, Conversation Coach and Conversation Coach Lite). A total

of 28% (7/25) of the evaluated AAC apps were a low-cost or

free version of an app that was also available in a fully featured

version for a greater cost (Tables 3 and 4). None of the evaluated

translation apps was a different version of the same app. The

majority of the AAC apps were available only for the iOS

platform (19/25, 76%), cost less than Can $25 (US $18.9) or

were free (16/25, 64%), and were only available in English

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 15http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

(14/25, 56%). Only 3 AAC apps indicated informed design

(SLP: Apps2Speak and Voice4u AAC; end user: image2talk),

and only 1 AAC app included a translation function

(LetMeTalk). Most translation apps were only available in the

iOS marketplace (15/17, 88%), were available for 2 years or

longer (13/17, 76%), were free (15/17, 88%), and offered

technical support (16/17, 94%). All translation apps had recent

software updates and had some offline functions (Table 5).

Figure 3. Flow diagram summarizing the results of the identification, selection, evaluation, and final recommendation phases involved in the 2017

communication app replication review. The presentation of results was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

flow diagram template AAC: augmentative and alternative communication; ADLs: activities of daily living; LTRC: long-term residential care.

The majority of cApps contained at least some PCC features

(AAC: 14/25, 56%; translation: 11/17, 65%; Table 6). The AAC

apps with the highest number of PCC features were GoTalk

NOW LITE (11/14), GoTalk Start (11/14), and CommunicoTool

2 (10/14). The translation apps with the highest number of PCC

features were Google Translate (6/7), TableTopTranslator (6/7),

Translator with Speech HD (6/7), Microsoft Translator (5/7),

Multi Translate Voice: Say It (5/7), and Voice Translator

Reverso (5/7). All AAC apps supported hearing loss, included

multiple display representations, multiple output modes, and a

text-to-speech function, while very few included a

speech-to-speech function or a translation function.

Quality Assessment

All cApps that underwent final quality assessment were highly

rated (Table 7). On the basis of researcher consensus, the

following cApps were deemed to be best suited for supporting

communication between residents living in LTRC and their

caregivers during ADLs: GoTalk NOW LITE, CommunicoTool

2, Google Translate, and Microsoft Translate (Multimedia

Appendix 1). Although App2Speak was rated higher than GoTalk

NOW LITE, the app contained fewer PCC features than GoTalk

NOW LITE (8 and 11, respectively) and fewer features than

CommunicoTool 2. Importantly, App2Speak included only 2

custom features (add personal pictures and voice recordings)

compared with GoTalk NOW LITE, which contained 4 custom

features.

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 16http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Stability of Evaluated Communication Apps Over Time

Between the 2015 review and the 2017 replication review, the

number of AAC apps identified in the iOS marketplace increased

by 31.4% (from 614 to 807) and the number of identified

translation apps increased exponentially (from 138 to 2041;

Figures 2 and 3). In all, 61% (14/23) of the eligible AAC apps

in the 2015 review also met study eligibility in the 2017 review

(Tables 3 and 4). Of the 2015 eligible/evaluated AAC apps,

35% (8/23) were no longer available in the marketplace in 2017.

Two AAC apps identified in the 2015 review were excluded in

the 2017 review because one required a substantial change for

use in the LTRC setting and the other included images that were

not adult appropriate (eg, child cartoon images; SoundingBoard

and TouchChat AAC, respectively). Finally, 1 AAC app was

excluded from the 2015 review but was deemed eligible in the

2017 review (Gabby). The images in Gabby were categorized

as not adult appropriate in the original 2015 review; however,

the updated version of Gabby contained images that were

considered adult appropriate. Except for the SayHi app, which

is no longer available in the App Store, all translation apps that

were eligible in the 2015 review also met study inclusion in the

2017 review.

A similar number of AAC apps were evaluated in the 2015 and

the 2017 reviews (n=23 and n=25, respectively). Of the 25 AAC

apps evaluated in the 2017 review, 3 (12%) were the same

version of the app evaluated in the 2015 review (App2Speak,

Conversation Coach, and image2talk) and 9 (36%) were a

different version of the same app evaluated in the 2015 review

(eg, Conversation Coach Lite and Sono Flex Lite; Tables 3 and

4). Notably, CommunicoTool Adult (2015 review) was no longer

available in the App Store and was replaced by CommunicoTool

2 (2017 review). For this study, CommunicoTool 2 was

considered a different version of the same app because its

features were quite like those of CommunicoTool Adult.

Although GoTalk NOW was the only version of the app that

was evaluated in the 2015 review, GoTalk NOW, GoTalk NOW

PLUS, GoTalk NOW LITE, and GoTalk Start were all eligible

versions of the same app in the 2017 review. After applying the

secondary selection criteria, only GoTalk NOW LITE and

GoTalk Start were evaluated in the 2017 review because these

versions were classified as low cost (<Can $100 [US $75.5]).

The cost of GoTalk NOW increased by 22% (from Can $89.99

[US $67.9] to Can $109.99 [US $83.1]). The number of

evaluated translation apps increased by 325% in the 2017 review

(from 4 to 17). Three of the four translation apps (75%)

evaluated in the 2015 review were also evaluated in the 2017

review.

Stability of Communication App Features Over Time

Over the 2-year period, the majority of the evaluated cApps

were only available for the iOS marketplace; however, the

largest increase was observed in the percentage of AAC apps

available across both iOS and Android platforms (167%; from

2/23, 9% to 6/25, 24%), and a decrease occurred among the

translation apps (76%; from 2/4, 50% to 2/12, 12%). Between

2015 and 2017, the majority of AAC apps continued to indicate

that adults living with a communication disability were the

target user, while translation apps continued to target the general

users. There was a 44% increase in the percentage of AAC apps

with no indication of informed design (from 14/23, 61% to

22/25, 88%), and the largest percent decrease was seen in AAC

apps that included a translation function (69%; from 2/23, 13%

to 1/25, 4%). For the secondary selection features (Table 5),

only two remained stable over time across cApps: in the

marketplace for 2 years or more and available technical support.

The largest percent change increase was observed in AAC apps

that were free (135%; from 4/23, 17% to 10/25, 40%) or cost

less than Can $25 (US $18.9; 167%; from 2/23, 9% to 6/25,

24%) and in translation apps that included web-based and offline

capability (300%; from 1/4, 25% to 17/17, 100%).

For PCC features, the overall percentage of AAC apps that

included approximately 50% to 74% of the PCC features

remained stable over the 2-year period (48%), whereas the

percentage of evaluated translation apps with at least some PCC

features decreased by 37% between 2015 and 2017 (from 3/4,

75% to 8/17, 47%; Table 5). Many of the custom PCC features

included in AAC apps remained stable over the 2-year period,

specifically features that supported hearing loss, used a natural

sounding voice output, included a text-to-speech function, and

offered an option to add/save personalized photos/images.

Between 2015 and 2017, the largest percent increase occurred

among AAC apps that included an option to customize

vocabulary (127%; from 7/23, 30% to 17/25, 68%), whereas

the largest decrease occurred for the percentage of AAC apps

that included a translation option. Over the 2-year period,

translation apps witnessed the largest decrease among the

percentage of apps that included a natural sounding voice (68%;

from 3/4, 75% to 11/25, 24%), whereas the percentage of

translation apps that supported two-way communication

decreased by 45% (from 3/4, 75% to 7/25, 41%).

Discussion

Principal Findings

This study’s comprehensive review of cApps available in the

iOS marketplace aimed to identify and assess the features and

quality of cApps that would be most appropriate for use with

residents living in LTRC homes. In addition, this study

examined the stability/instability of cApps over a 2-year period.

The 2015 review process culminated in selecting 2 AAC apps

(CommunicoTool Adult and GoTalk NOW) and 2 language

translation apps (Google Translate and TableTop Translate)

that provided the most suitable overall content and usability

features for enhancing communication between care staff and

residents living in LTRC. For purposes of augmenting

communication with images, video, sound, and text, these top

2 AAC apps contained features and functionality that promote

a multimodal understanding of messages, appealing and

high-quality images and audio/video capabilities, and the

capacity to customize content to individuals. One of these AAC

cApps, GoTalk NOW, has received an endorsement from

researchers in the field of AAC [40]. The top 2 language

translation apps in the 2015 review offered features that provided

high-quality voices, accurate translation, the capacity to save

commonly translated phrases, and versatility in translating across

modalities (eg, text to speech). Together, these 4 cApps provide

JMIR Aging 2020 | vol. 3 | iss. 1 | e17136 | p. 17http://aging.jmir.org/2020/1/e17136/

(page number not for citation purposes)

Wilson et alJMIR AGING

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

a promising starting point for integrating communication

technology into LTRC person-centered care practices. It is

interesting to note that, during the predownload initial quality

assessment, the top recommended cApps did not have the

highest median quality assessment ratings. For example,

Alexicom Elements Adult, Talkforme, App2Speak, and

CommunicAide received the highest median rating for AAC

apps, and SayHi Translate was the highest-rated translation app.

However, once the shortlisted cApps were downloaded and

used, the respective features, functionality, and usability of the

top recommended cApps were judged to be superior to all the

other downloaded apps. For example, CommunicoTool Adult

included the option to have a human voice, the built-in photos

were clear and relevant, and the app was customizable, and

GoTalk NOW was easy to use, had several built-in and

customizable features, and the stock pictures were relevant.

Google Translate allowed for web-based and offline (ie, saved

phrases) functions, was free, and was easy to use, whereas

TableTop Translator supported face-to-face conversation with

a unique split-screen function.

Overall, the majority of cApps evaluated in 2015 (20/27, 74%)

demonstrated marketplace stability over a 2-year period. In the

2017 review, only one of the top recommended cApps from the

2015 review was replaced with a newly evaluated translation

app, whereas the top AAC apps were different versions of the

same app recommended in the 2015 review. The decision to

recommend Microsoft Translator over TableTop Translator

was based on several factors. The visual interface quality, the

sound quality, and the visual interface presentation of Microsoft

Translator were rated higher compared with TableTop

Translator. Also, TableTop Translator uses Microsoft for

translations, had not undergone any recent updates, and the app

crashed several times while attempting to translate when using

the app. Although CommunicoTool Adult was replaced by

CommunicoTool 2, the newer version remained a top

recommended cApp for use in the LTRC setting to support

caregiver-resident communication during ADLs.

Although many of the AAC apps evaluated in 2015 and in 2017

include features and functionality that could support

communication between LTRC staff and residents (ie, support

hearing loss, included multiple display options, a text-to-speech

function, add personal photos; technical support), less than half

of AAC apps contained some (ie, 50%-74%) of these features.

For instance, in both reviews, there was a limited number of

evaluated AAC apps that supported two-way communication,

included a speech-to-speech option or a translation function,

supported vision loss, or provided options to add/save

personalized text or videos. Moreover, the majority of AAC

apps provided no indication of informed design, with less than

10% indicating SLP involvement in the design/development of

the app. Importantly, it appears that none of the cApps, including

the ones shortlisted in the 2015 and 2017 reviews, were

specifically developed to support PCC, particularly with frail

elderly residents living with sensory, motor, or cognitive

impairments, and/or language barriers. For example, the stored

voices linked to images in AAC apps (eg, speaking the word

orange when clicking on image of orange) and translator’s

voices have not taken into account the potential impact of

speaker/listener dialect or accent, nor the use of male versus

female voice, on residents’and staff’s ability to understand the

voice. The images on these apps are also generic, which means

that some of the images are not relevant for the LTRC context

because they have a different appearance than what is

encountered in the resident’s specific care environment (eg,

dining area, shower, and meals or snacks). Using voices from

the same dialect of the residents with voice qualities that

accommodate to the high-frequency hearing loss of many

residents, along with images that align with elderly residents’

current and previous life experiences, is an important way to

reduce the information processing demands of residents and

maximize their familiarity with the content. In view of older

adults’reluctance to learn new technologies, making the content

as relevant and meaningful to their life experience and current

needs should promote person-centered care and, thereby, greater

acceptance of MCT and cApps during their daily activities.

All AAC apps that were evaluated in both the 2015 and 2017

reviews claimed to support hearing loss by offering volume

control and input for listening devices (eg, earbuds). In addition,

some AAC apps provided an option to adjust the speech rate,

to customize the voice output, or to use a speech-to-text

function. Although these features can enhance one’s listening

experience, the technical specifications are not capable of being

adapted to different hearing loss profiles. Therefore, future apps

found in the iOS marketplace should be designed to interface

with hearing aid apps (eg, Mobile Ears) running on mobile

devices [41]. The significance of meeting the hearing health

needs of elderly residents in LTRC is apparent when considering

that most residents in LTRC are living with hearing loss [42]

and that failing to accommodate to their hearing loss can have

repercussions on their cognitive and social well-being [2,43,44].

For example, Amieva et al [45] reported that people living with

hearing loss who use hearing aids or other assisted listening

devices are much less likely to experience cognitive decline

than those who do not use hearing supportive devices. These

authors also provided evidence that ensuring persons with

hearing loss use their hearing aids is an important factor in the

person’s likelihood of using new technologies (eg, smartphone).

Given that hearing aid use enables persons to engage in

communication, it would follow that the use of other types of

communication enhancement devices, such as cApps with

features that support hearing, could be used in conjunction with

hearing aids to help maintain cognitive and social functioning

in aging and dementia. Future research is needed to explore the

potential long-term benefits to cognitive and social health

associated with regular use of hearing aids (or other assistive

listening devices) and cApps in LTRC.

Many older adults in LTRC also experience significant declines

in their vision [46]. This challenge can be addressed to some

extent by ensuring residents are wearing appropriate corrective

lenses and that the size of the images and text fonts is enough

for each resident’s vision needs. However, because MCT devices

are small, the upper range of expanding images and text is highly

constrained by the size of the device. Consequently, there is a