VOL 63: APRIL • AVRIL 2017

|

Canadian Family Physician • Le Médecin de famille canadien

295

Praxis

An efcient tool for the primary

care management of menopause

Susan Goldstein MD CCFP FCFP NCMP

T

he Canadian population is aging. In 2014, women

aged 50 to 54 years comprised the largest age cohort

of women in Canada,

1

an age at which most women

begin the menopause transition. This might be accom-

panied by vasomotor symptoms (VMS), genitouri-

nary syndrome of menopause (GSM), mood and sleep

changes, joint pain, and more.

2

After the early termination of the Women’s Health

Initiative in 2002, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT)

became highly controversial because of reported

increases in the risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular

disease.

3

In response, interest in nonhormonal options

grew and many have been evaluated (eg, antidepressants,

gabapentin, pregabalin, clonidine, phytoestrogens). While

they were effective for mild VMS, these medications are

not particularly effective for moderate to severe VMS or

for some of the other menopause-related concerns.

4,5

New guidelines

Menopausal hormone therapy remains the most effec-

tive treatment of VMS, and is also indicated for GSM

(previously called vulvovaginal atrophy) and bone pro-

tection.

4,6,7

Recently, the Women’s Health Initiative data

have been reevaluated to better guide physicians in

patient selection, with risks being reevaluated and strat-

ified by age and time since menopause.

8

New guide-

lines have been created, with the consensus that MHT

is safest for those younger than 60 years and within

10 years of menopause

4,6

and might be continued for

some women after age 65.

9

This is clinically relevant, as

new evidence is emerging indicating that many women

continue to experience substantial symptoms well into

their 60s, with a mean duration of VMS of more than

7 years and extending beyond 11 years for many.

10

With

no fixed duration of treatment, the guidelines now state

that MHT should be individualized to account for each

patient’s unique risk-benefit profile.

4,6

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certied

Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to

www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Can Fam Physician 2017;63:295-8

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à

www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro

d’avril 2017 à la page e219.

Many primary care clinicians have had little experi-

ence treating menopausal patients. New guidelines and

position statements, including those from the Society of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada,

4

the North

American Menopause Society,

7

and the International

Menopause Society,

6

help support health care providers

in caring for menopausal women. These statements by

leading organizations in mature women’s health include

recommendations that certain questions be asked of all

perimenopausal women.

4,6,7

However, existing meno-

pausal questionnaires, such as the Menopause-Specific

Quality of Life Questionnaire and Greene Climacteric

Scale, are lengthy and might not be ideal for use in the

primary care setting.

With the needs of busy primary care physicians in

mind, I have developed a quick menopausal screen-

ing questionnaire called the Menopause Quick 6 (MQ6)

(Figure 1).

4,6

This 6-question scale assesses menopausal

symptoms for which there are evidence-based treatment

options while providing a patient-centred assessment

to guide treatment choices. This short questionnaire,

written in lay language, can be used during any clinical

encounter, including a periodic health examination.

These 6 questions were selected because they elicit

helpful information that can guide management deci-

2,4,6,10-12

sions, as described in Table 1.

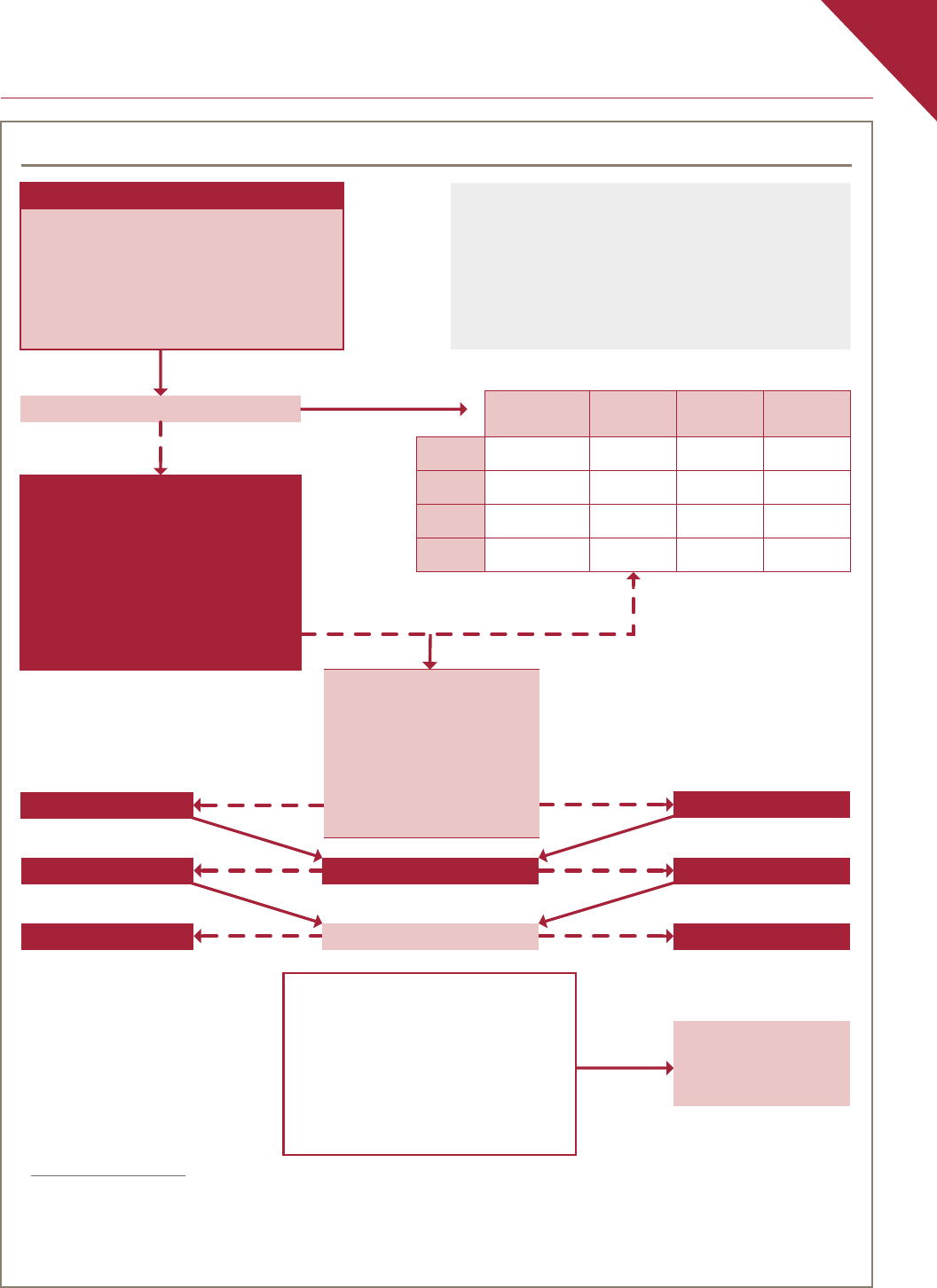

Putting the MQ6 into practice

The MQ6 was designed to be a quick and efficient tool

for primary care practice. The information elicited from

the 6 questions can guide evidence-based treatment

decisions, as set out in the algorithm in Figure 2.

5

As the algorithm specifies, when hormone therapy

is indicated and there are no contraindications to MHT,

then a transdermal preparation, which avoids first-pass

hepatic metabolism, is recommended for women with

comorbidities that increase cardiovascular risk, includ-

ing risk of venous thromboembolism or stroke (based

on observational data).

11

As the progestogen in the MHT regimen provides

endometrial protection, patients who have undergone

a hysterectomy require only estrogen therapy. When

endometrial protection is required, the use of either

estrogen-progestogen therapy or a tissue-selective

estrogen complex is recommended.

4

A tissue-selective

estrogen complex recently approved for use in Canada

combines conjugated equine estrogen with a selective

296

Canadian Family Physician

•

Le Médecin de famille canadien

|

VOL 63: APRIL • AVRIL 2017

Praxis

estrogen receptor modulator (bazedoxifene), the latter

component providing endometrial protection while

eliminating the need for a progestogen.

In the first year after menopause begins, women

will often bleed when taking a continuous MHT regi-

men, so a cyclic regimen is preferred.

11

Cyclic regimens

usually include a steady dose of an estrogen for days

1 to 25 or 1 to 31 of the month, accompanied by a

progestogen for 12 to 14 days of the month, resulting in

withdrawal bleeding. Continuous regimens use steady

daily doses of an estrogen and progestogen.

13

Of note, we are now treating with lower-dose regi-

mens of MHT, which do not always provide sufficient

treatment of the local symptoms of GSM. For adequate

treatment of local symptoms, the addition of vaginal

estrogen therapy should be considered.

Figure 1. The Menopause Quick 6 questionnaire: If a patient answers yes to any of questions 1 to 4, she might be

a candidate for treatment, and further exploration and assessment is warranted. The Society of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists of Canada and International Menopause Society guidelines recommend that questions 2 to 6 be

asked of all perimenopausal women.

4,6

Any changes

in your

periods?

Are you

having any

hot ˜ashes?

Any vaginal

dryness or

pain, or sexual

concerns?

Any bladder

How is your

How is

issues or

sleep?

your mood?

incontinence?

Table 1. How to use the information elicited by questions that comprise the Menopause Quick 6

QUESTION INTERPRETATION

Q1: Any changes in your periods? Menstrual irregularities signal imminent menopause. A recent study found that when VMS start

before the cessation of menses, they can be expected to last longer (median 11.8 y) than VMS

that start after the LMP (3.4 y).

10

Further, when prescribing MHT for women who are still cycling

irregularly or within 1 y of their LMP, a cyclic hormone regimen should be used.

11

If the LMP was

more than 1 y ago, continuous regimens can be offered. For all women with cessation of menses

younger than 45 y, MHT is recommended

Q2: Are you having any hot Up to 80% of menopausal women experience VMS. When these are mild, many lifestyle and

ashes? nonhormonal interventions can be effective. Moderate to severe VMS are treated most

effectively by hormone therapy

4,6

Q3: Any vaginal dryness or pain, The term vulvovaginal atrophy has been replaced by genitourinary syndrome of menopause,

or any sexual concerns? reecting the changes to the vulva, vagina, and urinary tract and to sexual functioning owing

to the menopausal drop in estrogen. Many women are reluctant to talk about their vaginal or

Q4: Any bladder issues or

sexual concerns, bladder issues, or incontinence, yet these can have a substantial negative effect

incontinence?

on quality of life. We have effective treatments for these symptoms, so we must ask

Q5: How is your sleep? Sleep disturbances are common during menopause and are most often attributed to hot

ashes.

2

Poor sleep can exacerbate mood and anxiety issues and contribute to cognitive

complaints and even weight gain

Q6: How is your mood? Menopause is a high-risk time for rst-episode or recurrent depression.

12

In addition, anxiety

and irritability peak during perimenopause. Both SSRIs and SNRIs have been shown to be

effective for these mood disorders while having a benecial effect on VMS. Women who remain

symptomatic despite these medications might benet from hormonal augmentation

LMP—last menstrual period, MHT—menopausal hormone therapy, SNRI—serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI—selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitor, VMS—vasomotor symptoms.

VOL 63: APRIL • AVRIL 2017

|

Canadian Family Physician • Le Médecin de famille canadien

297

Praxis

Figure 2. Evidence-based algorithm for management of menopausal symptoms

• Active thromboembolic diagnosis

• Acute CVD

YES

• Recent cerebrovascular accident

• Pregnancy

NO

Any estrogen

Td estrogen preferred

Comorbidities?

• Diabetes mellitus

• Hypertension

• Smoking

• Obesity

• High lipid levels or CVD risk

• Gallstones

YES

NO

NO

NO

Hysterectomy?

YES

YES

EPT or TSEC

ET

Cyclic regimen

LMP > 1 y ago? Continuous regimen

GSM symptoms?

• Vaginal dryness, pain or dyspareunia,

or urinary symptoms

Consider adding

AND

additional vaginal ET

Lower dose of estrogen to be prescribed:

(cream, tablet, or ring)

˜ 0.625 mg of oral CEE, 1.0 mg of

oral estradiol, or 50 µg of Td estradiol

CBT—cognitive-behavioural therapy, CEE—conjugated equine estrogen, CVD—cardiovascular disease, EPT—estrogen-progestogen therapy, ET—estrogen therapy,

GSM—genitourinary syndrome of menopause, LMP—last menstrual period, MHT—menopausal hormone therapy, MQ6—Menopause Quick 6, OAB—overactive

bladder, SNRI—serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, Td—transdermal, TSEC—tissue-selective estrogen

complex, VMS—vasomotor symptoms.

*In this table, + indicates some evidence of efÿcacy, ++ indicates good evidence of efÿcacy, +++ indicates strong evidence of efÿcacy, and +/- suggests the

treatment might improve or worsen symptoms. Data from the North American Menopause Society.

5

MQ6

1. Menstrual pattern

2. VMS

3. Vaginal pain or dryness, or sexual concerns

4. Urinary incontinence or OAB

5. Sleep issues

6. Mood issues

NO

MHT indicated?

YES

Contraindications to MHT

• Unexplained vaginal bleeding

• Known or suspected breast cancer

• Acute liver disease

The MQ6 was developed as a brief screening tool to

identify the presence of menopause-related symptoms that

are amenable to therapy and for which there are approved

treatments. The MQ6 can be used either as a questionnaire

by patients while waiting for their appointments or as a

verbal screening tool by health care practitioners during a

medical encounter or periodic health examination

Nonhormonal management of symptoms

Gabapentin or

pregabalin

SSRI or

SNRI

Clonidine

CBT or

hypnosis

VMS* ++ ++ + +

GSM

Sleep

+++ +/-

Mood

+++

298

Canadian Family Physician

•

Le Médecin de famille canadien

|

VOL 63: APRIL • AVRIL 2 017

Praxis

Conclusion

Primary care clinicians are increasingly using measurement-

based care and integrating it into their electronic med-

ical record systems. The MQ6 can help fill a gap for

measurement-based care in mature women’s health. It

takes about 2 minutes to use the MQ6 questionnaire

with a perimenopausal patient, making it an efficient tool

for busy primary care clinicians.

Using the MQ6 ensures that clinicians are asking the

right questions in a standardized way. The accompa-

nying algorithm, guided by the answers to the MQ6, is

based on the latest evidence-based guidelines and can

facilitate clinical decisions in an area that has a con-

troversial and sometimes confusing history. From the

patient perspective, using these tools can help patients

engage to discuss sensitive issues and it reassures them

they are being cared for in a holistic manner.

Dr Goldstein is a family physician practising in Toronto, Ont, and Assistant

Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the

University of Toronto.

Acknowledgment

I thank Dr Wendy Wolfman, Mr Mike Hill, and Ms Christina Clark for their

contributions to this article.

Competing interests

Dr Goldstein has received honoraria for advisory board participation and

consultant fees from Pfizer and Merck.

References

1. Statistics Canada. Table 051-0001. Estimates of population, by age group and sex

for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2016.

Available from: www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id

=0510001&&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=31&tabMode=dataTable&csid=.

Accessed 2017 Feb 23.

2. Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A prospective

population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96(3):351-8.

3. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML,

et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal

women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled

trial. JAMA 2002;288(3):321-33.

4. Reid R, Abramson BL, Blake J, Desindes S, Dodin S, Johnston S, et al. Managing

menopause. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2014;36(9):830-8.

5. North American Menopause Society. Nonhormonal management of menopause-

associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of the North American

Menopause Society. Menopause 2015;22(11):1155-72.

6. Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A; IMS Writing Group. 2016 IMS recommenda-

tions on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric

2016;19(2):109-50. Epub 2016 Feb 12.

7. Shifren JL, Gass ML; NAMS Recommendations for Clinical Care of Midlife Women

Working Group. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for

clinical care of midlife women. Menopause 2014;21(10):1038-62.

8. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, Prentice RL,

et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention

and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized

trials. JAMA 2013;310(13):1353-68.

9. North American Menopause Society. The North American Menopause Society

statement on continuing use of systemic hormone therapy after age 65. Menopause

2015;22(7):693.

10. Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, Bromberger JT, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB,

et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition.

JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(4):531-9.

11. Panay N, Hamoda H, Arya R, Savvas M; British Menopause Society and Women’s

Health Concern. The 2013 British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern

recommendations on hormone replacement therapy. Menopause Int 2013;19(2):

59-68. Epub 2013 May 23.

12. Soares CN. Can depression be a menopause-associated risk? BMC Med 2010;8:79.

13. Brown TER. Practical issues in hormone therapy management. Can Pharm J

2010;143(Suppl 2):S12-3.e1.