The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 1/9

THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND STUDENTS ON AND OFF CAMPUS:

Rights, Responsibilities, and Repercussions

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,

or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech,

or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble,

and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

~ FIRST AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969)

At a public high school in Des Moines,

Iowa, students wore black armbands

as a silent protest against the Vietnam

War. The school district suspended the

students, claiming that they feared the

protest would cause a disruption at

school. However, the school district

could point to no concrete evidence

that such a disruption would occur, or

ever had occurred, as a result of similar

protests. The students' parents sued

the school for violating their children's

right to free speech.

The Supreme Court ruled that “neither students nor teachers shed their constitutional rights to

freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” In declaring the suspension

unconstitutional, the Court stated: “[U]ndifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not

enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression.” In order to justify suppression of

speech, school officials must be able to prove that the conduct in question would “materially and

substantially interfere” with the operation of the school or the rights of other students. Justice

Potter Stewart agreed with this outcome, but wrote a separate, concurring opinion stating that

children are not necessarily guaranteed the full extent of First Amendment rights.

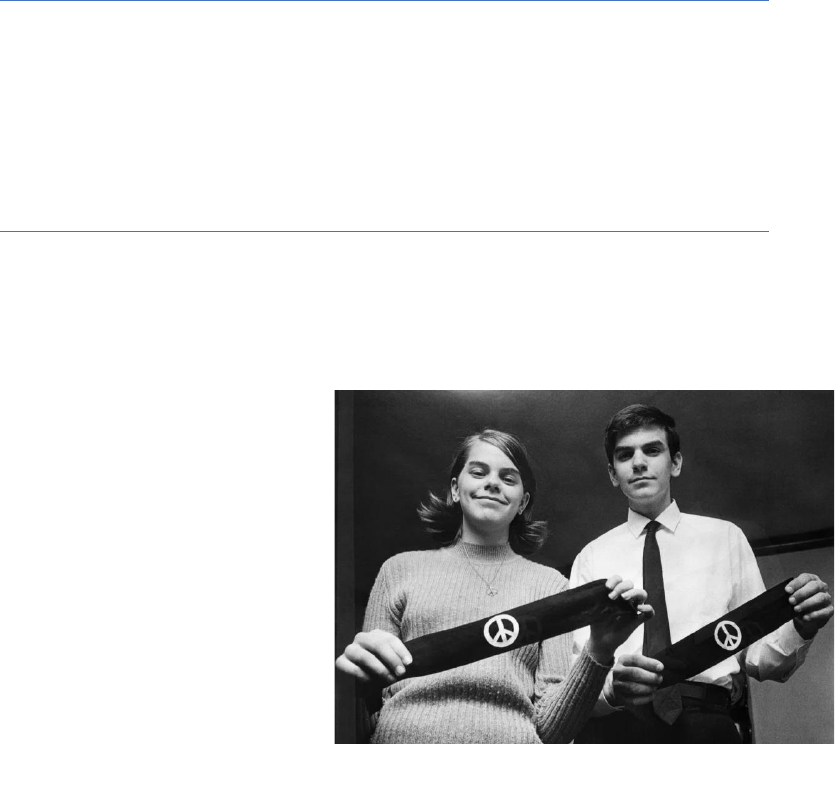

Des Moines, Iowa, students Mary Beth Tinker and her brother, John display

two black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. Bettmann—Getty Images

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 2/9

Other Cases to Consider:

> Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d 744 (5th Cir. 1966)

Three years before the Supreme Court decided Tinker, students at the all-

Black Booker T. Washington High School in Mississippi began wearing

buttons, proclaiming “One Man One Vote,” to protest racial discrimination in

voting and other aspects of public life. The high school principal banned the

buttons, saying they had no relevance to the students’ education and “would

cause commotion.” Three parents sued the school.

The Fifth Circuit Court unanimously ruled in favor of the students, holding that school officials “cannot

infringe on their students’ right to free and unrestricted expression as guaranteed to them under the

First Amendment to the Constitution, where the exercise of such rights in the school buildings and

schoolrooms do not materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate

discipline in the operation of the school.”

> Guiles v. Marineau, 461 F.3d 320 (2d Cir. 2006)

A 13-year old student was disciplined for wearing a T-shirt with images depicting President George

W. Bush as a chicken-hawk president who had previously used alcohol and cocaine.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals found that absent any evidence of disruption, school officials

violated the student’s free speech rights under the Tinker standard.

> Nuxoll v. Indian Prairie School District 204 (2007)

The Gay/Straight Alliance, a student club at Neuqua Valley High School, hosts a “Day of Silence,”

intended to draw attention to the harassment of gay people. It is part of a national event sponsored

by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. In response, the Alliance Defence Fund (ADF), a

conservative Christian legal organization, promotes a “Day of Truth'' to be held on the school day

following the “Day of Silence.”

Heidi Zamecnik, one of the students who disapproved of homosexuality, honored the “Day of Truth”

by wearing a t-shirt that read: “Be Happy, Not Gay” on the back. School officials asked Zamecnik to

ink out the phrase “Not Gay” because it violated a school policy forbidding “derogatory comments”

referring to sexual orientation, among other characteristics.

The following year, Zamecnik, now joined by fellow student Alexander Nuxoll, again wanted to wear

the shirt on the Day of Truth. This time, school officials suggested alternatives, including the slogan,

“Be Happy, Be Straight” and an ADF-produced “Day of Truth” shirt saying “The Truth Cannot Be

Silenced.” Zamecnik and Nuxoll refused those options and, with the help of the Alliance Defence Fund,

filed a lawsuit challenging the actions of the school officials.

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court ruling that students have a First

Amendment right to wear shirts stating “Be Happy, Not Gay.” The Court said that the school had not

demonstrated that wearing the shirts would cause “substantial disruption, finding the slogan “Be

Happy, Not Gay” to be “only tepidly negative.” “A school that permits advocacy of the rights of

homosexual students cannot be allowed to stifle criticism of homosexuality,” Seventh Circuit Judge

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 3/9

Richard Posner wrote. “People in our society do not have a legal right to prevent criticism of their

beliefs or even their way of life.”

See also:

● Harper v. Poway Unified School (9th Cir. 2007).

● Chambers v. Babbitt (D. Minn. 2001)

> Dariano v. Morgan Hills U.S.D. (9th Cir. 2014)

A group of Caucasian students attended their school’s annual Cinco de Mayo celebration, wearing

American flag T-shirts. The school had a “history of violence among students, some gang-related and

some drawn along racial lines.” Several students, including some of Mexican descent, expressed

concerns to the Assistant Principal that the shirts would lead to a physical altercation. The Assistant

Principal directed the students either to turn their shirts inside out or take them off, explaining that

he was concerned for their safety. The students refused, and the Assistant Principal sent them home

for the day with an excused absence. The students sued, alleging violations of their federal and

California constitutional rights to freedom of expression.

The Court held the students' freedom of expression claims failed because it was reasonable for

officials to proceed as though the threat of a potentially violent disturbance was real, and the officials'

actions were tailored to avert violence and focused on student safety.

> Barnes v. Liberty High School (2018)

Barnes, an Oregon high school student, came to a politics class discussion about immigration wearing

a T-shirt that said “Donald J. Trump Border Wall Construction Co.,” and “The Wall Just Got 10 Feet

Taller.” An assistant principal told Barnes that he needed to cover the shirt because a student and a

teacher said it offended them. Barnes refused and was removed from the class and suspended,

although the suspension was later rescinded. Barnes sued.

The District Court sided with Barnes’ defense: “School

officials may not suppress student speech based on the

‘mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness

that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint’ or ‘an

urgent wish to avoid the controversy which might result

from the expression.’” The School District settled the suit,

agreeing to pay $25,000 for Barnes’ legal fees and to have

the principal write him an apology.

The pro-Trump T-shirt that led to Barnes’

suspension. U.S. District Court Exhibit.

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 4/9

Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986)

Bethel High School’s disciplinary code included

a rule prohibiting conduct which "substantially

interferes with the educational process . . .

including the use of obscene, profane

language or gestures." At a school assembly

with 600 of his fellow students, Matthew

Fraser nominated his friend for school vice

president with a speech full of sexual

innuendos (a speech he had run past teachers

who cautioned him about it, but did not tell

him violated school policy). During Fraser’s

speech, some students hooted, yelled, and

acted out certain parts. Fraser was suspended

from school for two days. Fraser sued over the

suspension, alleging a violation of his First

Amendment rights. His case ultimately made it

to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court upheld the suspension and found that it was appropriate for the school to

prohibit the use of vulgar and offensive language. The Court found Fraser’s lewd speech

inconsistent with the "fundamental values of public school education," and in that way,

distinguished it from the political speech the Court previously had protected in Tinker.

“The schools, as instruments of the state, may determine that the essential lessons of civil,

mature conduct cannot be conveyed in a school that tolerates lewd, indecent, or offensive

speech and conduct such as that indulged in by this confused boy.”

“The pervasive sexual innuendo in Fraser’s speech was plainly offensive to both teachers and

students — indeed, to any mature person. By glorifying male sexuality, and in its verbal content,

the speech was acutely insulting to teenage girl students. The speech could well be seriously

damaging to its less mature audience, many of whom were only 14 years old and on the threshold

of awareness of human sexuality.”

Matthew Fraser, 18 Feb 1988, Spanaway, Washington, Image by ©

Bettmann/CORBIS

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 5/9

Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. (1988)

Hazelwood East High School’s newspaper was written and edited by students in the journalism

class. Under the school's practice, before the paper was published, the journalism teacher

submitted page proofs to the school's principal. The principal objected to two stories: one that

described school students' experiences with pregnancy and another article discussing the impact

of divorce on students at the school.

The principal was concerned that the unnamed students in the pregnancy story might still be

identified from the text, and also that the article's references to sexual activity and birth control

were inappropriate for some of the younger students. The principal objected to the divorce

article, which included complaints by a student about her father's conduct, because the parents

had not been given an opportunity to respond to the remarks or to consent to their publication.

In a 5-to-3 decision, the Supreme Court held that schools must be able to set high standards for

student speech disseminated under their auspices, and that schools retained the right to refuse

to sponsor speech that was "inconsistent with 'the shared values of a civilized social order,'" and

so the principal did not offend the First Amendment by exercising editorial control over the

content of student speech because his actions were "reasonably related to legitimate

pedagogical concerns."

Censored pages from the May 13, 1983 issue

of the Hazelwood East High School Spectrum.

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 6/9

Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007)

At a school-sponsored, off-campus event, a high school student held up a banner with the

message “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS,” a slang reference to smoking marijuana. The Principal took the

banner away and suspended the student for ten days, citing the school’s policy against the display

of material that promotes the illegal use of drugs. The student sued, alleging a violation of his

First Amendment rights.

Determining that it could “discern no meaningful distinction between celebrating illegal drug use

in the midst of fellow students and outright advocacy or promotion,” the Supreme Court

(reversing the Ninth Circuit) held that public high schools may “restrict student speech at a school

event, when that speech is reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use.” In so doing, the

Court affirmed that the speech rights of public school students are not as extensive as those

adults normally enjoy, and that the protective standards set by Tinker would not always be

applied.

Original banner now hanging in the Newseum in Washington, DC

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 7/9

Mahanoy Area School Dist. v. B.L., 594 U.S. ___ (2021)

A public high school student tried out for and failed to make her school’s varsity cheerleading

team, instead only making the junior varsity team. Over the weekend and away from school, the

student posted a picture of herself with her middle finger raised on Snapchat with the caption

“F**k school f**k softball f**k cheer f**k everything.” The photo was visible to about 250 people,

many of whom were fellow high school students and some of whom were cheerleaders. Several

students who saw the captioned photo approached the coach and expressed concern that the

snap was inappropriate. The coaches decided the student’s snap violated team and school rules,

which the student had acknowledged before joining the team, and she was suspended from the

junior varsity team for a year. The student sued the school, alleging her suspension violated the

First Amendment.

In its decision, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment limits but does not entirely

prohibit regulation of off-campus student speech by public school officials. The Court

acknowledged that schools could have a substantial interest in regulating certain kinds of off-

campus conduct. But the decision sets out three features of free speech protections for public

school students and boundaries for public school officials online or off campus, as opposed to on

campus.

“First, a school will rarely stand in loco parentis when a student speaks off campus.” (The phrase

in loco parentis means in the place of a student’s parents or legal guardians.)

“Second, from the student speaker’s perspective, regulations of off-campus speech, when

coupled with regulations of on-campus speech, include all the speech a student utters during the

full 24-hour day. That means courts must be more skeptical of a school’s efforts to regulate off-

campus speech, for doing so may mean the student cannot engage in that kind of speech at all.”

Finally, “the school itself has an interest in protecting a student’s unpopular expression,

especially when the expression takes place off campus, because America’s public schools are the

nurseries of democracy.”

The Court found the student’s off-campus speech was protected by the First Amendment, and

therefore the school district’s decision to suspend B.L. from the cheerleading team was

unconstitutional. Specifically, the Court held that the circumstances of the student’s speech

were the responsibility of her parents; and that her speech did not cause “substantial disruption”

or threaten harm to the rights of others.

“It might be tempting to dismiss [the student] B. L.’s words as unworthy of the robust First

Amendment protections discussed herein. But sometimes it is necessary to protect the

superfluous in order to preserve the necessary.”

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 8/9

Other Cases to Consider:

> Doninger v. Niehoff, 642 F.3d 334 (2d Cir. 2011)

A high school junior brought suit alleging that her First Amendment rights were violated when the

district barred her from running for senior class secretary after she posted a derogatory blog on an

independent website stating that the “d*****bags in central office” had canceled a school event and

urged students and parents to call complaints into the district to “piss off” the superintendent. The

Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled for the school district given the disruptive impact of the speech.

> J.S. v. Blue Mountain School District, 650 F.3d. 915 (2011)

In 2007, J.S. a student at Blue Mountain Middle School in Pennsylvania, was suspended for ten days, for

making a parody MySpace profile for her principal, portraying him as a sex addict who hit on students

and parents. Her family sued, arguing that the school could not discipline her for her off-campus speech.

In September 2008, a federal judge ruled that the school officials did not violate J.S. 's free-speech rights,

stating that school officials have the authority to punish "lewd and vulgar speech" about the school or

officials, even if the speech occurs outside of school.

In February 2010, a panel of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals also ruled in favor of the school district.

The same day, another panel of the Third Circuit ruled in favor of Justin Layshock, a student who had

also been punished for creating an online parody of his principal. The full Third Circuit Court of Appeals

heard arguments in this case on June 3, 2010, and a year later it ruled in favor of J.S. and Layshock. The

Supreme Court declined to hear the case, leaving the Circuit court ruling in favor of the students' free

speech rights to stand.

> Kowalski v. Berkeley County Schools, 652 F.3d 565 (4th Cir. 2011)

A student set up a MySpace webpage primarily dedicated to ridiculing a fellow student. In response to

the student’s harassment complaint, the school investigated and determined that Kowalski had created

a “hate website,” in violation of the school’s policy against “harassment, bullying, and intimidation.”

The school imposed suspensions on Kowalski.

Kowalski sued, alleging that the suspension violated her First Amendment and Due Process rights, and

argued that hers was "private out-of-school speech." The court found that the sanctions had been

permissible as Kowalski had used the Internet to orchestrate a targeted attack on a classmate, and did

so in a manner that was sufficiently connected to the school environment as to implicate the school’s

recognized authority to discipline speech which "materially and substantially interfere[d] with the

requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school and collid[ed] with the rights of

others."

> Bell v. Itawamba County School Board, (5th Cir. 2015)

A high school student created and posted a rap song on Facebook and YouTube that criticized two

Caucasian high school football coaches for allegedly sexually inappropriate comments toward African-

American female students. One of the coaches reported the song and the school suspended the student

and placed him in an alternative school for the remainder of the grading period.

The student sued alleging school officials violated his First Amendment free-speech rights. The District

court sided with the school; the Court of Appeals sided with Bell, but then the case went to a rehearing

by the full Fifth Circuit Court. The full Fifth Circuit was divided but the majority ruled that the song,

The First Amendment and Students On and Off Campus 9/9

which featured profanity and arguably threatening language, could be considered substantially

disruptive to the school environment.

See other similar cases:

• M.L. v. San Benito Independent Consolidated School District (5th Cir.)

• D.J.M. v. Hannibal Public School District (8th Cir.)

• Wynar v. Douglas County Schools (9th Cir.)

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

• Tinker v. Des Moines | United States Courts

• Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier | United States Courts

• Morse v. Frederick | United States Courts

• Digging into Mahanoy v. B.L. with New York Times Supreme Court Legal

Correspondent Adam Liptak, program co-hosted by the American Bar Public

Education Division and Sacramento Federal Judicial Library and Learning Center

Foundation.