Report

by the Comptroller

and Auditor General

HM Revenue & Customs, HM Treasury

The management

oftaxexpenditures

HC 46 SESSION 2019-20 14 FEBRUARY 2020

A picture of the National Audit Office logo

Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely.

Our public audit perspective helps Parliament hold

government to account and improve publicservices.

The National Audit Office (NAO) helps Parliament hold government to account for the

way it spends public money. It is independent of government and the civil service.

TheComptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Gareth Davies, is an Officer of the

House of Commons and leads the NAO. The C&AG certifies the accounts of all

government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory

authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether government isdelivering

value for money on behalf of the public, concluding on whether resources have been

used efficiently, effectively and with economy. The NAO identifies ways that government

can make better use of public money to improve people’s lives. Itmeasures this impact

annually. In 2018 the NAO’s work led to a positive financial impact through reduced

costs, improved service delivery, or other benefits to citizens, of £539 million.

Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General

Ordered by the House of Commons

to be printed on 12 February 2020

This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the

National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of

Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act

Gareth Davies

Comptroller and Auditor General

National Audit Office

11 February 2020

HC 46 | £10.00

HM Revenue & Customs, HM Treasury

The management

oftaxexpenditures

This report examines the economy, efficiency and

effectiveness of how the exchequer departments used

their resources with regard to the design, administration,

monitoring, evaluation and management of tax expenditures.

© National Audit Office 2020

The material featured in this document is subject to

National Audit Office (NAO) copyright. The material

may be copied or reproduced for non-commercial

purposes only, namely reproduction for research,

private study or for limited internal circulation within

an organisation for the purpose of review.

Copying for non-commercial purposes is subject

to the material being accompanied by a sufficient

acknowledgement, reproduced accurately, and not

being used in a misleading context. To reproduce

NAO copyright material for any other use, you must

contact [email protected]. Please tell us who you

are, the organisation you represent (if any) and how

and why you wish to use our material. Please include

your full contact details: name, address, telephone

number and email.

Please note that the material featured in this

document may not be reproduced for commercial

gain without the NAO’s express and direct

permission and that the NAO reserves its right to

pursue copyright infringement proceedings against

individuals or companies who reproduce material for

commercial gain without our permission.

Links to external websites were valid at the time of

publication of this report. The National Audit Office

isnot responsible for the future validity of the links.

006585 02/20 NAO

The National Audit Office study team

consisted of:

Matthew Wilkins, Tim Bryant,

TraceyPayne and Ronan Smyth,

underthe direction of Andy Morrison.

This report can be found on the

National Audit Office website at

www.nao.org.uk

For further information about the

National Audit Office please contact:

National Audit Office

Press Office

157–197 Buckingham Palace Road

Victoria

London

SW1W 9SP

Tel: 020 7798 7400

Enquiries: www.nao.org.uk/contact-us

Website: www.nao.org.uk

Twitter: @NAOorguk

Contents

Key facts 4

Summary 5

Part One

The number and cost

oftaxexpenditures 14

Par t Two

The design and monitoring

oftaxexpenditures 24

Part Three

The evaluation and review

oftaxexpenditures 38

Appendix One

Our audit approach 46

Appendix Two

Our evidence base 48

Appendix Three

Key reports covering tax reliefs and

HMRC andHM Treasury’s response 51

If you are reading this document with a screen reader you may wish to use the bookmarks option to navigate through the parts. If

you require any of the graphics in another format, we can provide this on request. Please email us at www.nao.org.uk/contact-us

4 Key facts The management of tax expenditures

Key facts

£155bn

sum of the estimated

costs of ‘tax expenditures’

in 2018-19 (tax reliefs

supporting government

objectives)

5%

real increase in summed

estimated cost of tax

expenditures, 2014-15

to2018-19

£11bn

estimated 2018-19 cost

of tax expenditures with

published evaluations

since 2015

362

number of tax expenditures (tax reliefs supporting

governmenteconomic and social objectives)

111

number of tax expenditures that HM Revenue & Customs has costed

23

number of tax expenditures with a forecast cost of more

than£1billion in 2018-19

63

tax reliefs HM Treasury assessed for value for money as

part of a monitoring exercise by 2019

15

number of tax expenditures with published evaluations since 2015

The management of tax expenditures Summary 5

Summary

Introduction

1 The UK tax system had 1,190 tax reliefs as at October 2019. A tax relief reduces

the tax an individual or business owes. There are two broad categories of tax reliefs:

structural tax reliefs that are largely integral parts of the tax system and define the scope

and structure of tax (such as the personal tax allowance); and non-structural tax reliefs

where government opts not to collect tax to pursue social or economic objectives.

Non-structural tax reliefs are often referred to as ‘tax expenditures’ and we use this

description in this report. Examples include tax credits for companies’ research and

development (R&D) costs and income tax relief on pension contributions. Some tax

expenditures simply reflect a policy choice by ministers to support particular groups

or sectors (for example the housing market), while others are designed to incentivise

behaviour. Some tax reliefs can be difficult to classify because they have more than

oneobjective and include elements of both tax expenditures and structural reliefs.

2 Tax expenditures are an important part of public policy design. They cover most

areas of government activity, including welfare, housing, business, food, education,

health and transport. They can also make the tax system more complicated and less

transparent, and they could pose risks to public finances because their costs can rise

beyond expectations. Tax expenditures differ from public spending in that they reduce

the amount of tax collected, rather than consume resources after tax is collected.

However, they are similar in that both affect the public purse and can be used to

pursuediscrete policy objectives.

3 The UK had 362 tax expenditures in October 2019, with HM Revenue & Customs

(HMRC) reporting the cost of 111. These tax expenditures had a combined estimated

cost of £155 billion in 2018-19. Aggregating the cost of tax expenditures gives a sense

of their scale, but it does not reflect the amount of tax that would be generated if tax

expenditures were removed because some taxpayers would change their behaviour

andthere may be wider economic impacts.

4 Ministers propose policy changes to introduce or amend tax expenditures as part

of the Budget. Parliament undertakes scrutiny of tax policy including tax expenditures

as part of the Budget process and through the work of the Treasury Select Committee.

HM Treasury and HMRC (the exchequer departments) are responsible for all aspects

of the effective working of the UK tax system including tax expenditures. HM Treasury

is responsible for strategic oversight of the tax system and HMRC is responsible for

administering the system. The Accounting Officers of HM Treasury and HMRC are

accountable to the Committee of Public Accounts for the economy, efficiencyand

effectiveness of the resources they use to discharge their responsibilities, including

thework they carry out to manage tax expenditures.

6 Summary The management of tax expenditures

5 Along with the Committee of Public Accounts, we have repeatedly raised concerns

about the departments’ management of tax reliefs. In our 2014 report, Theeffective

management of tax reliefs, we found that neither department had frameworks or

principles to guide their administration of tax reliefs. In 2016, we reported that while HMRC

had developed internal guidelines for managing reliefs, staff did not understand they were

compulsory. In 2018, the Committee of Public Accounts concluded that HMRC did not

know whether a large number of tax reliefs were delivering value for money. HMRC and

HM Treasury have responded to our recommendations by increasing their oversight of

taxexpenditures and actively considering their value for money. In 2019, HMRC informed

the Committee that, whilst both HM Treasury and HMRC are responsible for advising

ministers, the prime responsibility for advising ministers on the value for money of tax

reliefs lies with HM Treasury.

6 In July 2019, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) identified the costs of tax

reliefs as one of four new fiscal risks to the public finances. The OBR was concerned

that: the government did not know the full cost of tax reliefs; that tax reliefs lacked

transparency and scrutiny; and added complexity to the tax system.

Scope of this report

7 This report examines the effectiveness of HM Treasury’s and HMRC’s use

of their resources in the management of tax expenditures. Government spending

is governed by HM Treasury’s Managing Public Money but there is no equivalent

guidance for tax expenditures. The rules governing the tax system are set out in

legislation which Parliament scrutinises through the Finance Bill process. The exchequer

departments provide information needed to support decision-making. How the

exchequer departments monitor and evaluate tax expenditures informs government’s

understanding of the value for money of tax expenditures. In this report we examine

howHM Treasury and HMRC manage tax expenditures overall and examine their

oversight and administration across the lifecycle of tax expenditures, specifically:

•

the number and cost of tax expenditures (Part One);

•

design and monitoring of tax expenditures (Part Two); and

•

the evaluation and review of tax expenditures (Part Three).

8 Under section 6 of the National Audit Act 1983, the Comptroller and Auditor

General (C&AG) examines the economy, efficiency and effectiveness of the way that

government departments use their resources in discharging their functions, including

themanagement of tax expenditures. Our assessment is informed by deeper dives

intohow the departments used their resources to administer and oversee nine

established tax expenditures and design three that were new or recently amended

(Figure 1 on pages 7 and 8). We have not setout to conclude on the value for money

of specific tax expenditures. Our audit approach is set out in Appendix One and our

evidence base in Appendix Two.

The management of tax expenditures Summary 7

Figure 1 shows Case study tax expenditures covered in this report

Figure 1

Case study tax expenditures covered in this report

We looked at tax expenditures which supported a range of objectives and had differing ages and cost

Description

Objective When introduced Cost 2018-19

1

(£m)

1

Zero rating of VAT on the construction and sale of

new dwellings (residential and charitable buildings).

Support housing construction Long-standing

(40+ years)

14,800

2

Relief from inheritance tax on agricultural property. Support continuity of

farmingbusiness

315

Research and Development (R&D) reliefs:

Support research and

development activity

Established

(6 to 39 years)

3

Small- and medium-sized enterprises 2,515

4

R&D expenditure credit

2

2,340

R&D reliefs provide an extra deduction from

companies’taxable income for R&D expenditure.

Loss-making companies can receive a tax credit.

5

Entrepreneurs’ relief – reduces capital gains tax

to10% for sales of certain assets (for example,

sellinga business or shares in a business).

Encourage enterprise 2,200

6

Patent box – reduces the corporation tax rate to

10%for profi ts from patented inventions.

Support commercialisation

of innovation, and attract and

retain intellectual property

1,150

7

Film tax relief – fi lm production companies can

claim additional corporation tax relief for fi lm

production expenditure in the UK.

3

Loss-making

companies can receive a tax credit.

Support UK film industry 550

8

Relief on employer National Insurance

Contributions for employees under 21.

Encourage employment

ofunder-21s

Recently established

(3 to 5 years)

610

9

Relief on employer National Insurance

Contributions for apprentices under 25.

Encourage apprenticeships 160

10

Enterprise investment scheme – a venture capital

scheme that grants income and capital gains tax

reliefs to individuals investing in small companies.

Encourage investment

in companies with high

potentialgrowth

New or

recentlyamended

720

4

11

Relief on stamp duty land tax for fi rst-timebuyers

(noduty or reduced rates on homes up to £500,000).

Support home ownership

andfirst-time buyers

520

12

Structures and buildings capital allowance

– companies carrying out capital works on

non-residential buildings can make a deduction

fromprofi ts over a 50-year period.

5

Support business investment –

6

8 Summary The management of tax expenditures

Figure 1 shows Case study tax expenditures covered in this report

Key findings

The number and cost of tax expenditures

9 Tax expenditures represent a large and growing cost to the Exchequer.

InJuly 2019, the OBR reported that the known cost of tax expenditures had risen in

thepast decade. Our analysis of latest data published by HMRC in October 2019 shows

that, between 2014-15 and 2018-19, the cost of tax expenditures increased by 5% in

realterms, from £147 billion to £155 billion (forecast). Twenty-three tax expenditures

each costing more than £1 billion accounted for 92% of the total forecast cost in

2018-19. The largest tax expenditures were the reliefs on pension contributions, the

reliefs from VAT on food and new dwellings, and the relief from capital gains tax on

people’s main homes (paragraphs 1.5, 1.15 to 1.17 and Figure 3).

10 HMRC has committed to publishing more information on the cost of tax

expenditures. HMRC has calculated the cost of 111 of 362 tax expenditures. It plans

toestimate the costs for more tax expenditures between 2020 and 2022, prioritising

those tax expenditures it regards as higher risk (paragraphs 1.5, and 1.18 to 1.19).

11 The number of tax expenditures presents government with a significant

oversight challenge. The International Monetary Fund states that tax expenditures

require the same amount of government oversight as public spending. The scale of tax

expenditures in the UK is larger than most other countries and it will be challenging to

give tax expenditures the same amount of attention as spending. HMRC is improving

its understanding of the different types of tax expenditures by categorising tax

expenditures by purpose. Its initial work indicates that many are intended to incentivise

behaviour. While HMRC’s new categorisation is useful in understanding the broad

types of tax expenditures, it is not sufficiently detailed to group those targeted at similar

sectors or those with similar social or economic objectives (paragraphs 1.6, 1.7, 1.13,

1.14, 1.20 to 1.21 and Figure 4).

Notes

1 Most 2018-19 costs are projections based on previous years’ actual data. Projections are shown in italics

todistinguishfrom actuals.

2 R&D expenditure credit is mainly claimed by large companies, although it is available to small- and medium-sized

enterprises in certain circumstances.

3 Expenditure must be on goods and services used or consumed in the UK to qualify for fi lm tax relief.

4 Cost is the total of the income tax (£600 million) and capital gains (£120 million) elements of the tax expenditure.

5 Some capital allowances have elements of both structural reliefs (that is, they help defi ne the boundaries and

thresholds ofthe tax system) and tax expenditures. Tax expenditures are tax reliefs which government uses

toencourage particular groups, activities or products in order to achieve economic or social objectives.

6 HM Revenue & Customs reports the total cost of all capital allowances rather than the cost of each allowance

suchasstructures andbuildings.

Source: National Audit Offi ce

Figure 1 continued

Case study tax expenditures covered in this report

The management of tax expenditures Summary 9

The design and monitoring of tax expenditures

12 The exchequer departments are improving their oversight of tax

expenditures. In 2016 HMRC set up a central team to oversee its management of tax

reliefs. The team identified the officials responsible for specific reliefs and established

compulsory guidance. It introduced a framework to record information on reliefs in a

consistent manner across the Department. In 2017, HM Treasury piloted monitoring

of tax expenditures, prioritising those with specific policy objectives worth more than

£40million a year. By 2019 it had informally assessed whether 63 tax reliefs werevalue

for money, as part of its policy-making process. The exchequer departments’ monitoring

processes are still in development, and not yet integrated with oneanother. They plan to

develop a single framework for administering and reviewing tax expenditures, drawing on

relevant UK and international good practice (paragraphs 2.9 to 2.14).

13 When designing tax expenditures, HM Treasury has not given enough

consideration to how it will measure impact. When designing a new tax expenditure

HM Treasury undertakes many of the activities that we would expect at this stage

including consulting with relevant stakeholders. However, we did not find any cases

among tax expenditures introduced since 2013 where government had set out plans

for their evaluation at design stage, or triggers for evaluation if costs or benefits differed

significantly from their forecasts (paragraphs 2.3 to 2.6 and Figure 9).

14 Some tax expenditures cost far more than government’s published forecasts

indicated. HMRC does not compare the actual costs of tax expenditures to the

government’s original published forecasts available to Parliament. HMRC told us that

published forecasts are made on a different basis to the actual costs and a number of

factors make meaningful comparison difficult. For example, the forecasts can include

the impact on public finances of other changes to the tax system, other elements of

tax revenue or wider economic impacts, which may not be directly comparable to the

full cost of the tax expenditure. Even so, HMRC could take these factors into account

to make meaningful comparisons, which would help it better understand costs. We

compared forecast and actual costs for 10 tax expenditures, adjusting for differences

as far as possible with the data available. The comparison indicated large differences

forsome tax expenditures:

•

For five tax expenditures introduced since 2013, including three of the four largest,

data indicated costs were generally in line with original forecasts.

•

For the R&D expenditure credit, and four smaller tax expenditures introduced

since2013, data indicated costs exceeded forecasts by50% or more.

It was more difficult to compare forecasts and actual costs for tax expenditures

introduced before 2013. However, we found that the costs of three of our case study

taxexpenditures had grown from around £1 billion in 2008-09 to around £5 billion in

2017-18, much faster than the trends indicated in published forecasts (paragraphs 2.16

to 2.20 and Figures 10 to 12).

10 Summary The management of tax expenditures

15 HMRC has not fully investigated some large changes in costs. Cost increases

may indicate that a tax expenditure is working well, or that it is being used in ways not

intended. However, this can be difficult to determine without a substantive assessment.

HMRC had identified reasons for large changes in cost for all the established case study

tax expenditures we looked at. However, it did not normally test how far the reasons

explained cost movements, or compare its costs estimates with other data. Of the nine

cases we looked at, HMRC checked cost changes against independent data for only

agricultural property relief and R&D reliefs. For R&D reliefs, HMRC compared the total

R&D companies had claimed in tax returns for UK and overseas activity, with national

statistics on total UK (only) R&D activity. This comparison revealed that the R&D activity

companies had claimed was rising more quickly, and in 2016-17 exceeded all UK R&D

activity by 43%. HMRC is in the process of investigating the reasons for trends in data

(paragraphs 2.17, 2.21 to 2.24 and Figure 13).

16 R&D tax reliefs have been subject to increased levels of abuse. HMRC does

not hold data on tax lost from abuse and error for all tax expenditures. However, it has

developed a single view of the 63 main compliance risks it faces. Six of these risks

are specific to tax reliefs. Some of the other risks partly arise from tax reliefs, although

HMRC’s data do not show the significance of reliefs. Of the six tax relief-specific risks

it has identified, the risks were increasing for three. The risk arising from the R&D tax

expenditures was increasing the most. In 2017 and 2018 HMRC identified more tax

at risk from poor-quality R&D claims, and from abuse by companies with a limited UK

presence. In 2018 HMRC substantially increased its estimate oftax at risk from the R&D

tax expenditures to a level which indicated further action wasrequired. The time needed

to train new staff and develop new systems has affectedthe pace of HMRC’s response

(paragraphs 2.25 to 2.27).

The evaluation and review of tax expenditures

17 HMRC has formally evaluated only a minority of tax expenditures. HMRC

commissions and undertakes evaluations of few tax expenditures. Since 2015, HMRC

has published evaluations of 15 tax expenditures, representing just 7% (£11 billion) of

theaggregate forecast cost of tax expenditures in 2018-19. HMRC has evaluated only

five of 23 tax expenditures costing more than £1 billion, and less than half of the large

tax expenditures experiencing the fastest cost growth (paragraphs 3.2 to 3.4).

18 HMRC’s evaluations of tax expenditures suggest that their effectiveness

varies widely. Evaluations published since 2015 by HMRC have assessed the impact

of 13 of the 15 tax expenditures covered. These evaluations found that seven of these

tax expenditures (costing £3.6 billion in 2018-19) were having a positive impact on

behaviour,and one (costing £1.4 billion) had had a mixed impact. However, five tax

expenditures costing £5.2 billion had only a limited impact. Notably, a 2017 evaluation

found that only 8% of people claiming entrepreneurs’ relief in the previous five years

saidit had influenced their investment decision-making. The relief costs the Exchequer

more than £2 billion a year (paragraph 3.6 and Figure 14).

The management of tax expenditures Summary 11

19 HM Treasury has developed internal, informal processes for assessing the

value for money of tax expenditures. HM Treasury reviews the tax system annually,

including tax expenditures, as part of the Budget. In addition to this HM Treasury started

a monitoring exercise in 2017 as a tool for collecting information and officials’ views

to help inform advice to ministers. HM Treasury’s monitoring assessments have rated

the value for money of 63 tax reliefs. HM Treasury told us these are internal, informal

assessments that do not represent the formal view of the Department and should

not be published because they are part of policy advice to ministers. We looked at

monitoring templates for eight case studies and found that the assessments ask many

of the questions we would expect, but that the quality of information underpinning the

assessments was variable. HM Treasury was better placed to assess tax expenditures

when it had information available from recent HMRC evaluations. In the case of the R&D

expenditure credit HM Treasury based its assessment on an evaluation of the previous

scheme aimed at large companies. HM Treasury undertakes limited quality assurance

ofits value-for-money assessments (paragraphs 1.22, 2.13, 3.7 to 3.12 and Figure 15).

20 There is no formal documentation specifying explicitly the departments’

accountabilities for the value for money of tax expenditures. In 2014, HMTreasury

set out its view on accountability for tax reliefs but it did not specifically consider

accountability for value for money. In 2019, HMRC informed the Committee of

Public Accounts that the broader question of the value for money of tax reliefs is the

responsibility of HM Treasury, with HMRC providing relevant advice as part of the tax

policy partnership in the normal way. Policy decisions on the value for money of tax

expenditures are for Treasury ministers, who are ultimately accountable to Parliament

for the tax system and policy. HM Treasury officials are accountable for providing

ministers with high quality advice to make those decisions. HMRC officials also carry

out administrative functions which influence the cost and impact of tax expenditures.

For example, clear guidance, promoting take-up to target groups, action to tackle

abuseand timely reporting can all help to improve value for money (paragraphs 1.8

to1.13, 2.25 to 2.27 and 3.13 to 3.16).

21 Public reporting has improved but does not yet provide the information

necessary to assess the value for money of tax expenditures. HM Treasury

ministers are accountable to Parliament for the value for money of tax expenditures.

Aspart of the legislative process the government publishes costings and ‘tax

information and impact notes’ and ministers outline their aims to Parliament. However,

government does not publish the information necessary for scrutiny of the value for

money of existing tax expenditures. HMRC’s statistical bulletin is much improved but

still contains very limited information on the benefits achieved by tax expenditures, only

limited commentary on their cost trends, and although HMRC included estimates for

the number of claimants for the first time in January 2019, there is no trend data on the

number of claimants. The bulletin does not explain how costs and benefits differ from

the original published forecasts. Other countries have more comprehensive evaluation

and reporting despite most having comparatively lower levels of tax expenditures

(paragraphs 1.8, 2.5 to 2.7, 3.15, 3.17 to 3.20 and Figure 16).

12 Summary The management of tax expenditures

Conclusion

22 At a forecast cost of £155 billion in 2018-19, tax expenditures represent an

important means by which government pursues economic and social objectives.

Evaluations show that their impact is not guaranteed, and many require careful

monitoring. We have previously raised concerns about how effectively government

is managing tax expenditures. Both HMRC and HM Treasury have responded to

our recommendations by increasing their oversight of tax expenditures and actively

considering their value for money.

23 While these steps are welcome, they are very much still in development.

Thelargenumber of tax expenditures means it will take time to identify and embed

goodpractices. Both departments need to make substantial progress and ensure

sufficient coverage and rigour in the work they undertake on this matter.

24 On their own these improvements will not be sufficient to address value-for-money

concerns unless the departments formally establish their accountabilities for tax

expenditures and enable greater transparency. Lessons can be learned from other

countries that have established clear arrangements for evaluating and reporting on tax

expenditures. We look to HM Treasury and HMRC to follow suit by clarifying arrangements

for value for money and improving the evaluation and public reporting of tax expenditures.

Recommendations

25 As the custodians of the tax system HMRC and HM Treasury are responsible

for assessing the cost and impact of tax expenditures and communicating this to

decision-makers. We recommend that:

HM Treasury should:

a establish a framework for designing and administering tax expenditures

that is commensurate with the large number of UK tax expenditures.

Theframework should draw on ‘Green Book’ principles, international good

practiceand stakeholder views;

b develop a robust methodology for assessing the value for money of different

types of tax expenditures, ensuring that assessments are quality-assured;

c consider specifying time-periods or triggers for evaluation and review when

designing each tax expenditure;

d each year review whether the objectives of tax expenditures still align with

government objectives; and

e establish and document clear requirements for officials to report concerns

about the value for money of tax expenditures to ministers, for example

byspecifying accountability arrangements.

The management of tax expenditures Summary 13

HMRC should:

f further develop categorisation of tax expenditures according to, for example,

their objectives, scale, age and risks, in order to inform the allocation of administrative

resources in proportion to the cost and impact that tax expenditures are intended

to achieve;

g identify and use independent data sources, where available, to further test

reasons for movements in the cost of high-priority tax expenditures;

h develop a more systematic approach to the evaluation of tax expenditures to

provide greater coverage. We estimate that the external cost of commissioning

evaluations of six tax expenditures a year would likely be between £1 million and

£1.5 million. This estimate does not include the cost of HMRC’s own internal costs,

which could be significant;

i develop an approach so that it understands and can report the differences

between actual and forecast cost for tax expenditures it regards as

high-priority in its published analysis. In cases where it is not feasible to make

acomparison for a high-priority tax expenditure, HMRC should explain why; and

j include trend data on the number of beneficiaries of tax expenditures in

published analysis, where possible, and take account of this within commentaries.

14 Part One The management of tax expenditures

Part One

The number and cost oftaxexpenditures

1.1 The UK had 1,190 tax reliefs as at October 2019. This part of the report examines:

•

the different types of tax reliefs;

•

oversight of tax expenditures and stakeholder concerns;

•

how the number and cost of tax expenditures has changed over time; and

•

understanding of the tax expenditures government needs to administer.

1.2 Part Two considers the design and monitoring of tax expenditures. Part Three

considers their evaluation and review.

Structural reliefs and tax expenditures

1.3 Tax reliefs reduce the tax an individual or business owes. Some can also lead

to apayment. There are two broad categories of tax reliefs: structural tax reliefs and

non-structural tax reliefs, normally referred to as tax expenditures. Structural tax reliefs

are largely integral parts of the tax system. These reliefs have various purposes including

defining the scope of taxes and making taxes more progressive (such as the personal

tax allowance).

1

Tax expenditures are reliefs where government opts not to collect tax

topursue social or economic objectives (Figure 2).

1.4 Tax expenditures are a diverse group, and can be large (such as tax relief on

pension contributions), complex (such as some corporation tax reliefs) or small tax reliefs

intended to recognise certain taxpayers (such as relief on war disablement benefits).

Some tax reliefs can be difficult to classify because they have features of bothtax

expenditures and structural reliefs. The nature of tax reliefs means that they canhave

more than one objective, some incentivise behaviour, while others simply reflect

agovernment policy choice to reduce the tax burden on particular groups or sectors.

1 A progressive tax is a tax that imposes a lower tax rate on low-income earners compared with those with a higher income.

The management of tax expenditures Part One 15

Figure 2 shows Types of tax relief in the UK tax system

1.5 The UK had 362 tax expenditures in October 2019, with HM Revenue & Customs

(HMRC) reporting the cost of 111. The combined cost of these was forecast to be

£155billion in 2018-19.

2

The combined cost does not represent the gain to the exchequer

should tax expenditures be abolished. Revenue generated from abolishing a relief is

likely to be lower as taxpayers change their behaviour and there may be wider economic

impacts. Twenty-three large tax expenditures – each forecast to cost more than £1billion

in 2018-19 – accounted for 92% of the total forecast cost (Figure3 overleaf). The list

in Figure3 is dominated by tax expenditures that provide relief from capital gains on

people’s homes,relief on pension contributions, relief from VAT for certain goods and

services, and reliefs to encourage saving and investment.

2 HM Revenue & Customs, Estimated Costs of Tax Reliefs, October 2019, available at https://assets.publishing.service.

gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/837766/191009_Bulletin_FINAL.pdf.

Figure 2

Types of tax relief in the UK tax system

There are two main types of tax relief. HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) reports costs for a minority of reliefs

Type

Definition Example Number Number where

HMRC reports

cost estimates

2

Aggregate 2018-19 cost

of reliefs where HMRC

reports estimates

(£bn)

1

Structural reliefs Define the boundaries

and thresholds of the

taxsystem.

Income tax

personal allowance.

828 85 271

2

Tax expenditures Encourage particular

groups, activities or

products in order to

achieve economic or

social objectives.

Relief on

contributions to

pension schemes.

362 111 155

Total

1,190 196 426

Notes

1

Costs are the value of the relief to the taxpayer. Costs will therefore change if tax rates are altered. The amount of tax revenue gained if reliefs were

to be removed is likely to be lower than costs as taxpayers would change their behaviour in response and there may be wider economic impacts.

2

Most cost estimates for 2018-19 are projections based on previous years’ actual data.

3

A relief may have tax expenditure and structural elements (that is, it can support government objectives and defi ne the tax system). For example,

mostcapital allowances are structural reliefs in that they replace company estimates of capital depreciation costs when calculating taxable profi t, but the

rates can be preferential where government wants to incentivise capital investment (for example investment in some oil and gas plant and machinery).

HMRC allocates reliefs to the type (that is, tax expenditure or structural) it deems most dominant.

Source: National Audit Offi ce and HM Revenue & Customs,

Estimated Costs of Tax Reliefs, October 2019, and HM Revenue & Customs,

Estimated cost of structural tax reliefs

, October 2019

16 Part One The management of tax expenditures

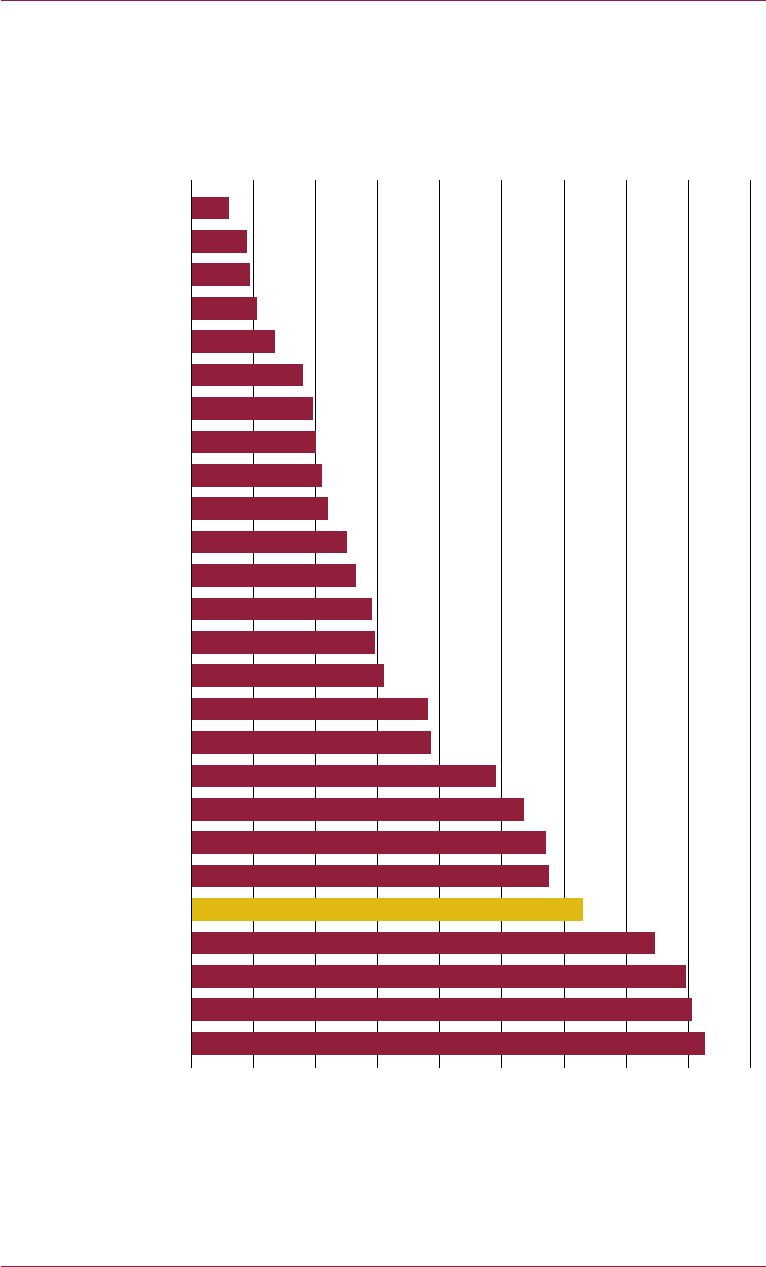

Figure 3 shows Cost of the largest tax expenditures in 2018-19 for which estimates are available

Figu

re 3

Cost

of the largest tax expenditures in 2018-19 for which estimates are available

The 23 largest tax expenditur

es had a forecast cost of £143 billion, 92% of the forecast cost of all tax expenditures.

The top five cost £98 billion (63%)

1

No

tes

1

This Figure shows all tax expenditures with a cost of more than £1 billion for 2018-19. Most cost estimates for 2018-19 are forecasts as they are projections

based on previous years’ actual data. The exceptions are rebated rate from hydrocarbon oils duty for gas oil (“red diesel”) and Employment Allowance where

actuals are available. Projected values are italicised to distinguish from actuals.

2

Research and development expenditure credit is mainly claimed by large companies, although available to small- and medium-sized enterprises

in certain circumstances.

3

Income of charities includes but is not limited to individual and company Gift Aid.

4

As shown in Figure 2, HM Revenue & Customs reports cost estimates for 111 of the 362 tax expenditures.

5

Tax expenditures are tax reliefs which government uses to encourage particular groups, activities or products in order to achieve economic

or social objectives.

6

Individual values do not sum to the total due to rounding.

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of data from HM Revenue & Customs, Estimated Costs of Tax Reliefs, October 2019

Exemption of gains arising on disposal of only or main residence

Employee contributions to registered pension schemes

Food zero-rated for VAT

Employer contributions to registered pension schemes

Construction of new dwellings zero-rated for VAT

Domestic passenger transport zero-rated for VAT

Domestic fuel and power at reduced rated for VAT

Individual savings accounts

Annual investment allowance

Drugs and supplies on prescription zero-rated for VAT

Research and development for small- and

medium-sized enterprises

Children’s clothing zero-rated for VAT

Exemption from inheritance tax of transfers on

death to surviving spouses

Ring-fence oil and gas trade, first-year capital

allowances for plant and machinery

Books, newspapers and magazines zero-rated for VAT

Patent box

Water and sewerage services zero-rated for VAT

Rebated rate from hydrocarbon oils duty for gas oil (‘red diesel’)

Research and development expenditure credit

2

Relief from capital gains tax for

entrepreneurs’ qualifying business disposals

Employment Allowance

Small traders below the turnover limit for VAT registration

Income of charities

0510 15 20 25 30

£ billion

2018-19 cost

14.8

5.4

4.7

3.3

3.1

3.1

2.5

2.5

2.4

2.3

2.2

2.2

2.2

2.0

2.0

1.9

1.6

1.5

1.2

26.7

20.4

18.3

17.4

The management of tax expenditures Part One 17

1.6 HMRC does not report the cost of 251 tax expenditures as it does not have

sufficient information on their use. The amount of data HMRC collects on usage of

tax expenditures varies. Taxpayers must specifically claim for some tax expenditures

– including some that can result in payments, such as the research and development

(R&D) reliefs. For others, such as VAT tax expenditures, data collected through tax

returns are not sufficient to estimate costs with certainty and HMRC estimates the

costsusing sources such as national statistics. Additionally, some reliefs are designed

so that people who do not owe any tax are not required to engage with the tax system

to claim their relief.

1.7 The best available data indicate that the cost of UK tax expenditures is relatively

high by international standards. Comparing the scale of UK tax expenditures with other

countries is difficult because of differences in tax regimes, variations in definitions of

what is a tax expenditure, and the absence of up-to-date data. However, in 2016, the

International Monetary Fund reported data indicating the cost of tax expenditures in

theUK was higher than most of 25 comparator countries (Figure 4 overleaf).

3

The scale

and large number of tax expenditures therefore presents a challenge to HM Treasury

and HMRC (the exchequer departments) in terms of oversight.

The oversight of tax expenditures and stakeholder concerns

1.8 Ministers account to Parliament for tax policy decisions and policy objectives

they seek to achieve by forgoing tax revenue. Parliamentary oversight of tax policy

is exercised during the passage of the Finance Bill (the Budget), and the work of the

Treasury Select Committee.

1.9 Ministers depend on the exchequer departments tooversee the tax system and

provide technical advice and feedback. In practice:

•

HM Treasury is responsible for strategic oversight of the tax system and seeks to

design sustainable taxes, deliver responsive tax policy and business tax reforms,

consistent with sound public finances. HM Treasury officials (explicitly theprincipal

accounting officer) are responsible for considering the effectiveness of tax policies

and providing evidence-based advice to ministers;

•

HMRC is responsible for delivering tax policies and maintaining the tax system,

alongside its duties to collect revenue due and tackling the tax gap; and

•

the two departments work in a policy partnership. They share an analysis function,

whose responsibilities include predicting the impact of changes to tax reliefs

proposed inthe Budget and producing statistics on tax reliefs and taxes in general.

1.10 The Accounting Officers of HM Treasury and HMRC are accountable to the

Committee of Public Accounts for the economic, efficient and effective use of their

resources in discharging their responsibilities. The roles and responsibilities of the

respective departments and thatofministers and Parliament are set out in Figure 5

onpage 19.

3 International Monetary Fund, United Kingdom Fiscal Transparency Evaluation, November 2016, page 24.

18 Part One The management of tax expenditures

Fi g ure 4 s hows Cost of tax e xpendit ure s as a perc ent age o f g r oss domesti c p r oduct (GDP ) i n selecte d c oun t ries a s r epo rt ed by th e Inte rnati o nal Monet ary Fund (I MF ) in 2016

Figu

re 4

Cost

of tax expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in

select

ed countries as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2016

Estimates pr

esented by IMF indicate that revenue forgone in the UK from tax expenditures

is high compar

ed with other countries

No

tes

1

Estimates are for 2010 unless otherwise stated.

2

Comparisons between countries should be treated with caution due to the different approaches taken

by different countries when reporting tax expenditures.

Sour

ce: International Monetary Fund, United Kingdom Fiscal Transparency Evaluation, 2016

Portugal

Switzerland

Turkey

Germany

Korea

Netherlands

Canada

Argentina

Peru

France

Norway

Denmark

Austria

Brazil

Greece

Spain

Mexico

Poland

Uruguay

Chile

Dominican Republic

United Kingdom 2014-15

United States

Guatemala 2009

Italy

Australia

012345678

Percentage of GDP

9

The management of tax expenditures Part One 19

Figure 5 shows Tax expenditures: roles and responsibilities

1.11 Accountability mechanisms and the way that Parliament checks and approves

government spending and taxation differ. Tax rules must be enshrined in legislation

to ensure taxpayers are obligated to comply. Parliament debates and approves all tax

policies, including tax expenditures before they can take effect. Changes can only be

achieved through legislation and there are no budget constraints, as the conditions to

qualify for a tax relief are set out in law and must be applied equally to all taxpayers.

In contrast Parliament considers government’s spending plans twice a year, and a

department has flexibility to transfer resources between its different activities without

Parliament’s approval.

Figure 5

Tax expenditures: roles and responsibilities

Ministers

Ministers’ decisions determine

thedesign of a new tax

expenditure oranychanges

to an existing tax expenditure

putforward in legislation.

Propose

changes to tax

expenditures

in the Budget/

Finance Bill

‘Policy

partnership’

for tax system,

including tax

expenditures

Provides advice to ministers on tax

expenditures in line with ministerial

and departmental objectives

HM Treasury

Oversees tax with aim of

delivering ministerial and

departmental objectives for

thetax system.

As part of this, leads on the

design of tax expenditures and

monitors their value for money

and relevance.

Parliament

Parliament debates Budget and

scrutinises Finance Bill and can

make changes before it is passed.

Treasury Select Committee

and Lords Economic Affairs

Committeescrutinise the Budget

and Finance Bill.

Committee of Public Accounts

scrutinises HM Revenue &

Customs’ and HM Treasury’s

useof resources (for example,

their staff).

HM Revenue & Customs

Provides technical advice

ontaxdesign.

Implements tax expenditures.

Monitors the use of

taxexpenditures.

Evaluates tax expenditures.

Source: National Audit Offi ce

Parliament has an opportunity to consider all new tax expenditures

20 Part One The management of tax expenditures

1.12 There is no formal guidance for how tax expenditures should be administered.

Managing public money guidance sets out accounting officers’ responsibilities for

their departments’ use of resources, and how to dispense these responsibilities.

4

Theguidance does not apply to tax expenditures as tax revenue forgone is not a

resource of a department but a decision to forgo tax made by a minister. The rules

governing the tax system are set out in legislation which is scrutinised through the

Finance Bill process.

1.13 Since 2014, both the National Audit Office and the Committee of Public Accounts

have reported several times on the management of tax reliefs by HMRC andHMTreasury.

In our November 2014 report, The effective management of tax reliefs, we found that

neither HM Treasury nor HMRC had established frameworks or principles to guide their

management of tax reliefs.

5

In 2016, we reported that HMRC had developed guidelines for

managing reliefs but HMRC staff we spoke to did not understand they were compulsory.

6

Most recently, in 2018, the Committee of Public Accounts concluded that HMRC did

not know whether a large number of tax reliefs delivered value for money.

7

HMRC and

HMTreasury have responded to our recommendations by increasing their oversight of

taxexpenditures and actively considering their value for money. In 2019, HMRC informed

the Committee that, whilst both HM Treasury and HMRC are responsible for advising

ministers, the prime responsibility for advising ministers on the value for money of tax

reliefs lies with HM Treasury.

1.14 A range of stakeholders, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Office

for Budget Responsibility (OBR), have expressed concerns about the large number of tax

expenditures and their impact upon the UK’s public finances. In 2019, the OBR identified

the cost of tax reliefs as one of four new fiscal risks to the UK.

8

TheOBRexpressed

concern that the government did not know the full cost of tax reliefs; that tax reliefs lack

transparency and adequate scrutiny; and add complexity to the tax system. The IMF

states that governments should give tax expenditures the same amount of attention as

public spending.

9

Appendix 3 sets out a timeline summarising stakeholder concerns and

HMTreasury and HMRC’s actions to improve management and transparency.

4 HM Treasury, Managing public money, July 2013, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/742188/Managing_Public_Money__MPM__2018.pdf.

5 Comptroller and Auditor General, The effective management of tax reliefs, Session2014-15, HC 785,

NationalAuditOffice, November 2014.

6 Comptroller and Auditor General, HM Revenue & Customs 2015-16 Accounts, Report by the Comptroller and

AuditorGeneral, July 2016.

7 HC Committee of Public Accounts, HMRC’s performance in 2017-18, Sixty-Sixth Report of Session 2017–2019,

HC1526,November 2018.

8 In its Fiscal risks report, July 2019, OBR set out its four new fiscal risks as: a no-deal Brexit; output gap

mismeasurement; the higher cost of tax reliefs; and discretionary fiscal loosening.

9 International Monetary Fund, How to notes: Tax Expenditure Reporting and Its Use in Fiscal Management.

A Guide for Developing Economies, March 2019.

The management of tax expenditures Part One 21

Changes in the number and cost of tax expenditures

1.15 In July 2019, the OBR reported that the known cost of tax expenditures had risen

in the past decade.

10

Our analysis of data published by HMRC, including the latest data

published in October 2019, shows that, between 2012-13 and 2018-19 the estimated

cost of tax expenditures increased in real terms from £126 billion to £155 billion

(forecast).

11

The forecast cost of tax expenditures in 2018-19 is equal to 7.3% of gross

domestic product (GDP).

1.16 The rate of growth has slowed in recent years, increasing in real terms by

£8billion (5%) from £147 billion in 2014-15.

12

The overall number of tax reliefs has been

relatively stable recently. The government added 14 new tax reliefs (including seven tax

expenditures) and removed four tax reliefs (all tax expenditures) between 2017 and 2019.

The government has also made changes to extend or restrict 47 other tax reliefs.

1.17 Between 2014-15 and 2018-19 corporation tax tax expenditures grew at a

faster rate than other tax expenditures (£2.6 billion, 57%), driven by the research and

development reliefs (combined cost up by £1.7 billion). The cost of VAT tax expenditures

grew most in absolute terms (£5.6 billion, 11%), due mainly to the relief on new dwellings

(up £4.6billion). The cost of the tax expenditures that can apply to either income tax or

corporation tax declined the most (£5.5 billion, 54%) (Figure 6 overleaf).

1.18 In November 2018, the Committee of Public Accounts recommended that HMRC

improve its understanding of the cost of those tax reliefs where it does not already

have that information.

13

Some existing cost estimates are also incomplete. For example,

HMRC’s cost estimates for some inheritance tax, income tax and capital gains tax

expenditures do not include the use of these tax expenditures by trusts – which are

arrangements used frequently in tax planning.

1.19 It will take time to improve information on the total cost of tax expenditures.

InApril2019 HMRC committed to reducing the number of un-costed tax reliefs

and saidthat it would focus on the 251 tax expenditures where costs are currently

unavailable. It has set up a project that will run in two stages over several years.

Thefirststage will involve a comprehensive review of currently available data to

provide indicative estimates for tax expenditures. The second stage will identify tax

expenditureswhere HMRC would need to collect or buy additional data to estimate

costs. HMRC intends topublish some new estimates in 2020 and expand coverage

in2021 and 2022. HMRCwill prioritise higher-risk tax expenditures.

14

10 Office for Budget Responsibility, Fiscal risks report, July 2019.

11 In Comptroller and Auditor General, Tax Reliefs, Session 2013-14, HC 1256, National Audit Office, April 2014 we

reported that the cost of tax expenditures was £101 billion in 2012-13. The figure of £126 billion reflects subsequent

revisions by HMRC to its cost estimates for 2012-13 and an adjustment to convert the estimates to 2018-19 prices.

Asshown at Figure 2, HMRC currently costs 111 of 362 tax expenditures. Most recent data is in HMRC, Estimated

Costs of Tax Reliefs, October 2019.

12 HM Revenue & Customs, Estimated Costs of Tax Reliefs, October 2019, available at https://assets.publishing.service.

gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/837766/191009_Bulletin_FINAL.pdf.

13 See footnote 7.

14 Letter from HMRC Chief Executive to the Chair of the Committee of Public Accounts, April 2019, available at: https://

www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/public-accounts/Correspondence/2017-19/Letter-from-Sir-

Jonathan-to-Chair-in-response-to-report-on-HMRC’s-Performance-in-17-18-recommendation-13-and-4-190430.pdf.

22 Part One The management of tax expenditures

Figure 6 shows Cost of tax expenditures (where known) by tax

Figu

re 6

Cost

of tax expenditures (where known) by tax

The cost of tax expenditur

es (where known) is increasing in real terms for most taxes

No

tes

1

All costs at 2018-19 prices.

2

Three tax expenditures can reduce income tax or, if used by companies, corporation tax.

3

Values are calculated by aggregating the estimated cost of individual tax expenditures. For many tax expenditures, the 2018-19

estimates are projections based on previous years’ actual data. 2018-19 values are therefore shown in italics.

4

The estimated costs of reliefs do not reflect the amount of tax that would be generated if these tax expenditures were removed

as it does not take into account behavioural change or wider economic impacts.

5

Costs shown are for the 111 tax expenditures HM Revenue & Customs reports costs on. As shown in Figure 2 there are 362 tax

expenditures in total.

6

Tax expenditures are tax reliefs which government uses to encourage particular groups, activities or products in order to achieve

economic or social objectives.

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of data from HM Revenue & Customs, Estimated Costs of Tax Reliefs, October 2019

Value Added Tax

Income tax

Capital gains tax

National Insurance Contributions

Income tax and corporation tax

2

Inheritance tax

Corporation tax

Other

01020304050

£ billion

60

49.9

55.5

28.9

29.0

27.8

30.3

17.2

21.2

10.2

4.7

5.0

3.2

4.6

7.2

3.9

4.2

2014-15 cost

2018-19 cost

The management of tax expenditures Part One 23

Figure 7 shows HM Revenue & Customs’ (HMRC’s) categorisation of tax expenditures

Understanding the tax expenditures government needs to prioritise

1.20 In 2019, HMRC completed a provisional classification of tax expenditures into three

sub-categories, reflecting the broad type of outcome that they are designed to achieve

(Figure 7). This work provides a basis on which to assess the scale of oversight that

may be required for each broad class of tax expenditure. For example, tax expenditures

intended to incentivise behaviour may require more detailed assessment than those

designed to benefit a specific group. The absolute cost, and change in the cost of atax

expenditure, will also affect the level of scrutiny that is appropriate.

1.21 While HMRC’s categorisation is useful in understanding the broad objectives of tax

expenditures, it is not sufficiently detailed to group tax expenditures targeted at similar

sectors or those with similar social or economic objectives. Such analysis is important

for HM Treasury to monitor the combined effect of tax forgone alongside spending,

forexample grant funding to business and business tax expenditures. In January 2020,

we reported that the cost of tax expenditures supporting business exceeds the cost of

direct business support grants.

15

1.22 HM Treasury reviews the tax system, including tax expenditures, annually as part of

the Budget. This process can result in more tax expenditures being introduced than the

number that are removed, depending on ministerial objectives and priorities for the tax

system. In 2011, the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS), which reports to the Chancellor

ofthe Exchequer, conducted a review of 155 tax reliefs and made recommendations

that 47 be abolished on the basis that they were either time-expired, there was

no ongoing policy rationale, the value was negligible, or the administrative burden

outweighed the benefit (Appendix 3). The OTS said at the time that there was clearly

scope to simplify a number of the remaining 883 reliefs but such work would logically be

part of wider projects reviewing specific taxes or the ways specific taxes affect particular

sectors.

16

Since 2011, OTS has considered specific tax reliefs as part of the wider

reviews it has conducted, such as of particular taxes or events that affect taxpayers.

15 Comptroller and Auditor General, Business support schemes, Session 2019-20, HC 20, National Audit Office,

January2020, paragraph 6.

16 Office of Tax Simplification, Review of tax reliefs final report, March 2011.

Figure 7

HM Revenue & Customs’ (HMRC’s) categorisation of tax expenditures

HMRC’s provisional classification shows that most tax expenditures are to incentivise behaviour or

benefit a specific group

HMRC classification

Approximate percentage of the

total of 362 tax expenditures (%)

Example

To incentivise a specific behaviour

40 Relief on contributions

topension schemes.

To benefit a specific group

40 Zero rating of VAT

onnew dwellings.

To serve a social purpose

20 Zero rating of VAT

onfood.

Source: National Audit Offi ce and HM Revenue & Customs

24 Par t Two The management of tax expenditures

Part Two

The design and monitoring oftaxexpenditures

2.1 As government auditors, we expect to see evidence of HM Revenue & Customs

(HMRC) and HM Treasury (the exchequer departments) effectively using their resources

to manage tax expenditures. In 2014 we set out the characteristics of an effective

system (Figure 8).

2.2 This part of the report considers the progress that HMRC and HM Treasury have

made in improving how they use their resources in their oversight of tax expenditures,

with a particular focus on the design and monitoring of taxexpenditures. Part Three

considers the evaluation and review of tax expenditures.

HM Treasury’s design of tax expenditures

2.3 In the run-up to each Budget or fiscal event, officials advise ministers on a variety

of tax measures including the design of new tax expenditures and the reform of existing

tax expenditures in line with ministerial objectives and HM Treasury’s responsibility to

ensure a sustainable tax system. Tax expenditure proposals can be made within the

context ofwider policy changes to the tax system or spending measures.

2.4 To understand the design process, we reviewed HM Treasury’s approach to

designing and revising three tax expenditures. We found that HM Treasury had

considered most of the factors we would have expected (Figure 9 on page 26).

HMTreasury had considered a range of options to deliver policy objectives for two

of our case studies andconsidered value for money for all three. It did least well in

articulating clear objectives for what the tax expenditures should achieve and how

theywould bemeasured andevaluated.

2.5 Following the design or revision of a new tax expenditure, the exchequer

departments normally publish ‘tax information and impact notes’ (TIINs). Wereviewed

TIINs for significant tax expenditures introduced since 2013 and found the gaps in

coverage for our three case studies were repeated.

17

The TIINs set out objectives

in general terms and did not provide baselines against which the benefits could

be measured. None of the TIINs set out criteria for evaluating or reviewing the

tax expenditure, such as triggers if costs or benefits differed significantly from

their forecasts.

17 In total we identified 14 new tax expenditures introduced since 2013, which each cost more than £50 million a year

by2018-19. Weidentified TIINs for 11 of these.

The management of tax expenditures Par t Two 25

2.6 HM Treasury normally conducts a public consultation on the introduction of a

tax expenditure at the design stage, unless it considers doing so will have adverse

market implications. It is not always feasible for the exchequer departments to test

for the behavioural impact of a new or revised tax expenditure given the difficulty of

isolating the impact of a tax expenditure from other potential influences such as the

economic environment.

2.7 The exchequer departments have also published ‘policy costings’ for the measures

in each Budget since 2011.

18

These are helpful to Parliament in scrutinising costs. They

contain information on the level of detail and behavioural assumptions behind estimated

costs, although this has reduced over the years. The Chartered Institute of Taxation, the

Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Institute for Government, who represent key users of

TIINs and policy costings, report that the level of detail has reduced over the years.

19

18 The Office for Budget Responsibility scrutinises each of the government’s costings of individual tax and annually managed

expenditure policy measures to decide whether to certify them as ‘reasonable and central’ estimates. It also assigns an

uncertainty rating for each costing, and explains the reasons behind those that it deems are highly uncertain.

19 Jill Rutter et al, Better Budgets: Making tax policy better, Chartered Institute of Taxation, Institute for Fiscal Studies,

Institute for Government, 2017, p. 33.

Figure 8

Characteristics of an effective system to design, manage and

evaluate tax expenditures

Decision on policy objective

Out of scope of this report

1

Evaluation and feedback

A process to evaluate the costs and

benefits of the tax expenditure has been

identified and is undertaken

Feedback from evaluation informs

changes and the knowledge base for

design of future tax reliefs

Administration and monitoring

The costs and benefits are monitored

and assessed

Process for delivering the relief

ismanaged

The risks are assessed and mitigated

Note

1

The Comptroller and Auditor General does not comment on the merits of policy objectives.

Source: National Audit Offi ce

Design

There is an adequate evidence base

available to support decisions over design

The objectives and intended

outcomesareclear

An impact assessment and option

appraisal was undertaken

Figure 8 shows Characteristics of an effective system to design, manage and evaluate tax expenditures

26 Part Two The management of tax expenditures

Figure 9

Issues considered by HM Treasury during design of our three case studies of new or recently

amended tax expenditures

For our three case studies, HM Treasury had considered most of the factors we would expect

First-time buyers’ relief

fromstamp duty land tax

Structures and buildings

capital allowance (SBA)

1

‘Risk to capital’ condition for

venture capital schemes relief

Context Part of a package of

housingmeasures

Part of a package with other

changes to capital allowances to

support business investment

One option in a package of

options to encourage high-risk

business investment following

the‘Patient Capital Review’

2

Issue

Objectives set out Yes in general terms

(not SMART)

3

Yes in general terms (not SMART) Yes in general terms (not SMART)

A range of tax options

(for example, different rates

ofrelief)

Yes No for SBA, but yes for other

options in the package

Yes

Compared to

spendingalternatives

No but part of a package

with spending measures

No Yes

Estimated costs/impacts

fortheoptions

Yes Yes for package as a whole Yes

Value for money Yes Yes Yes

Confidence in estimates

4

Yes Yes Yes

Differential impacts on different

sectors, regions and types

ofpeople

Yes Yes No

Risks of rewarding behaviour that

would have occurred anyway

Yes Yes Yes

Risk of the measure

beingabused/different

legalinterpretations

Yes Yes Yes

How well the measure or a

similarmeasure had, or had not,

worked in the past

Yes Yes Yes

HM Revenue & Customs’

administration costsquantified

Yes Yes No

Practical implementation issues Yes Yes Yes

How it will be evaluated No No No

Notes

1

Capital allowances have both structural and tax expenditure elements.

2

For risk to capital condition we have assessed whether the issues were considered for the overall package of options

HM Treasury was considering. Thelargest venture capital scheme is the enterprise investment scheme.

3

SMART objectives are those which are: specifi c, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

4

‘Confi dence in estimates’ refers to whether there has been consideration of how certain the forecasts are and/or

how sensitive they are to changestounderlying assumptions.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of HM Treasury documents

Figure 9 shows Issues considered by HM Treasury during design of our three case studies of new or recently amended tax expenditures

The management of tax expenditures Par t Two 27

Administration and monitoring of tax expenditures

2.8 HMRC administers most tax expenditures as part of its wider administration of each

tax stream. It manages some tax expenditures separately where they require specialist

knowledge or involve significant payments to taxpayers, such as research and development

(R&D) reliefs. As well as ensuring compliance with the rules, HMRC is responsible for

monitoring costs and benefits and evaluating tax expenditures. In 2014 we found some

good practice but also inconsistency and fragmentation in how HMRC managed reliefs,

with insufficient information-sharing on risks, costs and benefits.

20

In 2016, we encouraged

HMRC to approach each tax relief in a way that is in proportion to its risk.

21

2.9 HMRC has implemented all four of the recommendations relating to tax reliefs in

the National Audit Office’s 2016 report.

22

Specifically, they set up a small central team

in 2016 to improve management of tax reliefs, including tax expenditures. Theteam

introduced a process for tax reliefs and helped to coordinate its use. By 2019 the team

had finalised acomplete list of all tax reliefs for the first time and identified staff with lead

responsibilityfor each tax relief.

2.10 The team has established compulsory guidance and has developed a

frameworkof questions based on good practice to help staff with lead responsibility

for tax expenditures. This framework is designed to capture information on reliefs

in a consistent manner across the Department. The framework covers most of the

areas we would expect to see including costs, public awareness and promotion of

thetaxexpenditure, andarrangements for monitoring and evaluation.

2.11 The framework does not provide adequate guidance for all the risks affecting

tax expenditures, including risks of abuse; overlap with spending programmes; and

identification of the resources needed to administer the tax expenditure effectively.

However, when we looked at nine tax expenditures in more detail we found that

HMRChad considered risks to tax revenue in each case.

2.12 We held a workshop with HMRC staff to understand how they used the

frameworkand to identify possible areas for development. Staff with lead

responsibilityfor tax expenditures told us that the framework helped them manage

taxexpenditures. However, some of these staff said that the framework did not

change what they did in practice as they considered they were already effectively

managing their tax expenditures. Other staff said that following the framework

helpedtomaintainknowledge of tax expenditures.

20 Comptroller and Auditor General, The effective management of tax reliefs, Session2014-15, HC 785,

NationalAuditOffice, November 2014.

21 Comptroller and Auditor General, HM Revenue & Customs 2015-16 Accounts, Report by the Comptroller

andAuditorGeneral, National Audit Office, July 2016.

22 See footnote 21.

28 Par t Two The management of tax expenditures

2.13 HM Treasury has also improved its monitoring of tax expenditures. It has developed

a monitoring template to ask officials to review whether prominent tax expenditures

are achieving their objectives, informally assess their value for money, and consider the

case for reform. Following International Monetary Fund (IMF), National Audit Office and

Committee of PublicAccounts concerns, HM Treasury piloted a monitoring template in

2017 for 40tax reliefs costing more than £40 million with specific policy objectives. In

its process of providing ministerial advice, HM Treasury expanded coverage so that by

early 2019 it had assessed 63 tax reliefs. HM Treasury told us the framework is a tool for

collecting information and officials’ views to help inform advice to ministers. The quality

of these assessments is considered in Part Three.

2.14 HM Treasury has not integrated its monitoring with HMRC’s. HM Treasury’s current

monitoring template does not cover the design of tax expenditures and, of the 57

questions in HMRC’s framework, only eight address design. As of October 2019, the

departments reported that they were developing a single framework. HM Treasury was

considering what it could learn for how it appraises new tax expenditures from its ‘Green

Book’ guidance on appraising spending proposals and from international comparisons.

23

2.15 Neither HMRC nor HM Treasury differentiates between management of tax policy

as a whole and tax reliefs, meaning that it is not possible to set out the precise amount

of resources working on tax expenditures. HM Treasury reports that around 200 of its

staff work on tax policy overall.

Monitoring and forecasting the cost of tax expenditures

2.16 Accurate forecasting of future costs is inherently difficult, particularly for new

tax expenditures. Government’s published forecasts are prepared by HMRC and

scrutinisedby the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in its role as the government’s

official forecaster.

24

2.17 Increases in cost can indicate that a tax expenditure is working well. Conversely,

increases can also mean that a tax expenditure is being used in ways not intended.

Economic growth, inflation, policy changes and changes to underlying tax rates

can alsohave an effect. It is important that the exchequer departments understand

the reasons for changes in costs but these are often hard to determine without a

substantive assessment. Such assessments would ideally include comparisons of

expected and actual costs. However, HMRC does not compare the government’s

original published forecasts for new tax expenditures to their actual costs.

23 HM Treasury, The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation, 2019. Available at https://

www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent.

24 In order to carry out its statutory duties, OBR has a legal right of access to information and analysis across the public

sector. For tax matters this includes HMRC, where officials are required to produce any analysis, including draft

forecasts, that the OBR requires to fulfil its remit.

The management of tax expenditures Par t Two 29

2.18 HMRC told us that costs in its official statistics can appear to be very different

from published forecasts because they are prepared on a different basis. For example,

published forecasts assess the impact on public finances and can reflect:

•

reductions in the cost of other tax expenditures where taxpayers are expected

toswitch to a new and more generous tax expenditure;

•

the expected wider economic impacts of a new tax expenditure; and

•

the expected impact on public finances of related policy changes made at the

same time.

25

Forecasts are calculated on a National Accounts Basis, while the official statistics are

generally on an accruals basis (they represent the effects on the tax liabilities for each

year, not receipts in each year).

26

2.19 We compared government’s published forecasts with costs in official statistics

for nine new tax expenditures adjusting for differences as far as possible with the

data available.

27

These comparisons indicate that estimates for five tax expenditures,

including the three largest, were broadly in line or within government forecasts

(Figure10 on page 30). However, the comparisons also indicate that the costs of four

tax expenditures could be more than original forecasts by around 50% to 150%. We also

found that the cost of the R&D expenditure credit (primarily claimed by large companies)

phased in from 2013 was higher than internal government forecasts (Figure 11 on

page31).

28

Theexchequer departments do not report largedifferencesinexpected

andactual costs.

2.20 It was more difficult to compare the costs of established tax expenditures with

published government forecasts because projections cover a maximum of five years.

However, three of our case studies introduced before 2013 had published forecasts

covering longer periods as a result of several policy changes The combined cost of

these three tax expenditures increased from around £1 billion in 2008-09 to around £5