2

NANN Board of Directors

Lori Brittingham, MSN RN CNS ACCNS-N, President

Joan Rikli, MSN RN CPNP-PC NE-BC, President-Elect

Susan Meier, DNP APRN NNP-BC, Secretary-Treasurer

Lee Shirland, MS NNP-BC, NANNP Council Chair

Gail Bagwell, DNP APRN CNS

Taryn Edwards, MSN CRNP NNP-BC

Thomasine Farrell, BSN RNC-NC

Annie Rohan, PhD RN NNP-BC CPNP-PC FAANP

Elizabeth Sharpe, DNP NNP-BC

Rebecca South, BSN RNC-NIC

NANNP Council

Lee Shirland, MS APRN NNP-BC, NANNP Council Chair

Elizabeth Welch-Carre, MEd MS APRN NNP-BC, NANNP Council Chair-Elect

Sandra Bellini, DNP APRN NNP-BC

Kristin Howard, DNP APRN NNP-BC

Amy Koehn, PhD APRN NNP-BC

Barbara Snapp, DNP APRN NNP-BC

Moni Snell, MSN APRN NNP-BC RN

Tracy Wasserburger, MSN APRN NNP-BC RNC

Task Force for Revision of NNP Education Standards

Catherine Witt, PhD APRN NNP-BC, Chair

Suzanne Staebler, DNP APRN NNP-BC FAANP FAAN

Lori Bass Rubarth, PhD APRN NNP-BC

Sandra Bellini, DNP APRN NNP-BC CNE

Cheryl Ann Carlson, PhD APRN NNP-BC

Copyright © 2017 by the National Association of Neonatal Nurses. No part of this document may

be reproduced without the written consent of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses.

3

Introduction

Since the mid-1970s neonatal nurse practitioners (NNPs), previously known as neonatal nurse

clinicians, have demonstrated their value in the provision of health care to high-risk infants and

their families. Requirements for education, licensure, accreditation, and certification of NNPs have

been fluid, displaying wide variations among practice jurisdictions. NNPs have consistently

delivered high-quality care and have remained committed to maintaining standards of excellence as

they fulfill increasingly complex roles within the healthcare system.

NNPs are respected as professionals and have earned the trust of interprofessional colleagues and

the patients/families they serve. Trusted professionals must engage in continuous scrutiny to ensure

they keep pace with the ever-changing needs within the healthcare system and must be willing to

revise both preparation and requirements for entry-level and continuing practice, as reflected by the

most current evidence. This is especially true in the current healthcare environment, where nurses

and NNPs are faced with tumultuous changes in the way care is provided.

Professional accountability begins with ensuring the quality of nurse practitioners’ educational

preparation. It is the responsibility of the professional organizations for advanced practice nursing

(American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], National Organization of Nurse

Practitioner Faculties [NONPF]) to define the standards for graduate nursing education in the nurse

practitioner role. Recognizing that NNPs are part of the larger group of advanced practice

registered nurses (APRNs), the National Association of Neonatal Nurses (NANN) and the National

Association of Neonatal Nurse Practitioners (NANNP) collaborate with a number of regulatory,

licensing, education, and credentialing agencies to produce the most current education and

curriculum standards. In response to the expanding numbers and responsibilities of APRNs, the

APRN Consensus Work Group and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN)

APRN Advisory Committee met in 2008 and formed the APRN Joint Dialogue Work Group. They

developed an APRN regulatory model to clarify and ensure uniformity of APRN regulations. Their

consensus report "defines APRN practice, describes the APRN regulatory model, identifies the

titles to be used, defines specialty practice and preparation, describes the emergence of new roles

and population foci, and presents strategies for implementation" (APRN Consensus Work Group &

NCSBN APRN Advisory Committee, 2008, p. 5). In addition, the APRN Joint Dialogue Work

Group illustrated a need for the establishment of a "formal communication mechanism, LACE,

which includes those regulatory organizations that represent APRN licensure, accreditation,

certification, and education entities" to ensure ongoing effective dialogue among all APRN

stakeholders in these areas (p. 16).

According to AACN, "practice demands associated with an increasingly complex healthcare

system created a mandate for reassessing the education for clinical practice of all health

professionals, including nurses" (AACN, 2006, p. 4). In 2002 AACN convened a task force to

investigate the desirability of the practice doctorate in nursing (DNP). The task force proposed

doctoral-level education as an entry-level requirement for APRNs. This recommendation was

approved by the AACN membership in its 2006 document, The Essentials of Doctoral Education

for Advanced Nursing Practice (AACN, 2006).

AACN published The Essentials of Nursing Education for the Doctorate of Nursing Practice

(2006) to illustrate "curricular expectations that will guide and shape DNP Education." The

document outlines the "curricular elements and competencies that must be present in programs

conferring the doctor of nursing practice degree...and addresses the foundational competencies that

4

are core to all advanced nursing practice roles" (AACN, 2006, p. 8). Clarifying recommendations

regarding the DNP were published in 2015, which provided clarification on the DNP project,

practice hours and experiences, and curriculum considerations (AACN, 2015).

Although doctoral preparation for APRNs is a worthy goal, it is not yet clear when it will become a

mandatory degree for entry-level practice. In updating its Essentials for Master's Education in

Nursing (2011), AACN acknowledges that "Master's education remains a critical component of the

nursing education trajectory to prepare nurses who can address the gaps resulting from growing

healthcare needs and that...these Essentials are core for all master's programs in nursing and

provide the necessary curricular elements and framework, regardless of focus, major, or intended

practice setting" (AACN, 2011, p. 3). Currently, in 2017, there are a number of NNP programs

continuing to provide education and preparation at the master’s level.

Although APRNs are acknowledged as integral members of the healthcare system, there remains a

lack of consistency in regulations across state boundaries in the United States. The barriers to

practice created by the lack of standardization exacerbate the shortage of qualified NNPs that

already exists. With the release of the 2008 APRN Consensus Model, nurse practitioner (NP)

organizations and educational facilities have undertaken efforts to incorporate the model's

components. "Within education, NP programs have focused on changes to align educational tracks

with the NP populations delineated in the model. National organizations have supported these

efforts through collaborative work on the NP competencies that guide curriculum development"

(NONPF, 2013, p. 5).

NONPF, with representation from the major NP organizations, has developed core competencies

for the six population foci described in the APRN Consensus Model. These "NP Core

Competencies integrate and build upon existing master's and DNP core competencies and are

guidelines for educational programs" (NONPF, 2011, amended 2012, p.1). Each individual

population focus within the broader category of advanced practice nursing is charged with

delineating more specific standards of education for its own members. Thus, NANNP, a division of

NANN, defines the educational and preparation standards for those pursuing the NNP role.

In conclusion, the framework for NNP education is built upon the broad standards for advanced

practice nursing (AACN, 2006, 2011) and the evaluation criteria for nurse practitioner programs

(National Task Force on Nurse Practitioner Education, 2016). This document reflects the consensus

of the work summarized above and presented in the Criteria for Evaluation of Nurse Practitioner

Programs (National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 2016), The Consensus

Model for APRN Regulation (APRN Consensus Work Group & NCSBN APRN Advisory

Committee, 2008), Population-Focused Nurse Practitioner Competencies (NONPF, 2013), The

Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (AACN, 2006), and The

Essentials of Master’s Education in Nursing (AACN, 2011).

This document describes the minimum standards necessary for preparation of NNPs. These

standards are intended to be used in conjunction with other accreditation standards and tools in the

evaluation of graduate educational programs or tracks and reflect updated guidelines for Evaluation

Criteria for Nurse Practitioner Programs (National Task Force on Nurse Practitioner Education,

2016). This edition also adds additional information on use of simulation and addresses educational

criteria regarding care of the infant through the age of 2 years.

Designing or revising programs according to the recommendations in this guideline will ensure that

5

graduates receive the necessary preparation to practice at the novice level. The guidelines serve as

a tool for the development and evaluation of new NNP programs and as a self-study manual for

existing programs. The guidelines are especially valuable in today’s environment, in which hospital

administrators, directors, and managers may consider replacing NNPs with other providers who

have not received neonatal population–specific education. Given the educational components

needed to produce a competent, novice-level NNP, it is clear that filling the gaps with providers

who have a generalist education—such as physician assistants, pediatricians, or nurse practitioners

educated in other population foci—is not in the best interest of providing high-quality, safe, and

cost-effective neonatal care.

6

Each of the following program standard statements is followed by an elaboration that provides

important background on or a rationale for the standard. The statement of the standard is identified

by bold text.

I. Program Requirements

The NNP educational program must

A. be a formal neonatal nurse practitioner graduate or postgraduate (either post-

master’s certificate or postdoctoral) program that is awarded by an academic

institution and accredited by a nursing or nursing-related accrediting

organization recognized by the U.S. Department of Education or the Council

for Higher Education Accreditation

B. be awarded preapproval, pre-accreditation candidacy, or accreditation status

prior to the admission of students

C. be comprehensive at the graduate level

D. prepare the graduate for population-focused practice in the NNP role

E. be supported in its development, management, and evaluation by institutional

resources, facilities, and services

F. prepare the graduate to be eligible to take the national NNP certification exam.

Elaboration

Nurse practitioners are described by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) as

“licensed independent practitioners who practice in ambulatory, acute, and long-term care as

primary and/or specialty care providers. According to their practice population focus, NPs deliver

nursing and medical services to individuals, families, and groups” (AANP, 2013).

AANP recommends that NPs complete a formal graduate education program and have a

commitment to lifelong learning and professional self-development to ensure that they develop and

maintain the appropriate understanding of theory and level of clinical skills. AANP clearly

indicates that the graduate degree is needed for entry-level preparation and acknowledges that,

although most NP programs award the master’s degree, the shift toward awarding doctoral degrees

is increasing. This transition has occurred as a result of a 2004 recommendation by AACN that all

advanced practice nurses be prepared at the doctoral level by 2015 “with the degree title of doctor

of nursing practice, or DNP” (AACN, 2004b; AANP, 2010). However, it is unclear when the

doctoral degree will be mandatory for entry-level NP practice.

According to the Consensus Model for APRN Regulation (APRN Consensus Work Group &

NCSBN APRN Advisory Committee, 2008), all APRN education programs must undergo a

preapproval, preaccreditation, or accreditation process before students are admitted. The purpose of

this process is to ensure that students graduating from the program will be eligible for national

certification and licensure to practice and to ensure that programs meet all educational standards

7

before they admit students. Accredited MSN or DNP programs adding a neonatal NP track must

submit a substantive change report to their accreditation body and receive a letter of change

approval within the designated time period set forth by the accreditation body (Accreditation

Commission for Education in Nursing, 2016; Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, 2012).

The NNP provides population-focused health care to preterm (<37 weeks) and term neonates, and

infants and children up to 2 years of age.

To implement and maintain an effective NNP program or track, there must be an adequate number

of faculty, facilities, and services that support NNP students. There must be a sufficient number of

faculty with the necessary expertise to teach in the NNP program. As a necessary part of the

educational process, access to adequate classroom space, models, clinical simulations and

audiovisual aids, computer technology, and library resources is critical. When using alternative

delivery methods, a program is expected to provide or ensure that resources are available for the

students’ successful attainment of program objectives.

Graduates of NNP educational programs should be eligible to take the nationally recognized

certification exam. This national certification will assess the broad educational preparation of the

individual, including graduate core, APRN core, NNP role/core competencies, and the

competencies specific to the neonatal population (NONPF, 2013; NANNP, 2014).

II. Faculty and Faculty Organization

A. NNP programs must have sufficient faculty members with the preparation and

current expertise to adequately support the professional role development and

clinical management courses for NNP practice.

1. NNP program faculty members who teach the clinical components of the

program must maintain current licensure, state approval to practice as an

advanced practice nurse, and national certification as a neonatal nurse

practitioner.

2. NNP program faculty must demonstrate current, ongoing experience in

clinical practice as an NNP and in teaching through ongoing faculty

development activities designed to meet the needs of new and continuing

faculty members, including adjunct and clinical faculty (National Task

Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 2016).

B. Non-NNP faculty members must have expertise in the area in which they are

teaching.

C. NNP program faculty competence must be evaluated at regularly scheduled

intervals.

Elaboration

For successful implementation of the curriculum, faculty members must have the preparation,

knowledge base, and clinical skills appropriate to the neonatal area. Recognizing that no individual

faculty member can fill all roles, NNP programs need to maintain a sufficient number of qualified

8

faculty members who have the knowledge and competence appropriate to the neonatal area and

who are able to meet the objectives of the program and neonatal population–focused tracks.

NNP program faculty should include a mix of individuals with expertise and emphasis in research,

teaching, and clinical practice. Although it may be difficult for some faculty members to balance

research, practice, and teaching responsibilities, all faculty members who teach clinical courses

must maintain national certification as a neonatal nurse practitioner.

NNP faculty members may participate in or undertake various types of practice in addition to direct

patient care to maintain currency in practice. Maintaining this currency is important to ensuring

clinical competence in the area of teaching responsibility.

In the event that an NNP faculty member has less than 1 year of clinical or academic experience, it

is expected that a senior or experienced faculty member will mentor this individual in both clinical

and teaching responsibilities. Mentoring new and inexperienced faculty is a positive experience

that helps NNPs transition into the role of NNP faculty educator. Opportunities for continued

development in one’s area of research, teaching, and clinical practice should be available to all

faculty.

Similar to NNP faculty, other faculty who help support the NNP program must have the

preparation, knowledge base, and clinical skills appropriate to their area of teaching responsibility.

III. Practice Experience Requirements for Prospective Students

The equivalent of 2 years of full-time clinical practice experience (within the last 5

years) in the care of critically ill neonates or infants in critical care inpatient settings is

required before a student begins clinical courses. Students may enroll in preclinical

courses while obtaining the necessary practice experience.

Elaboration

NANN recognizes that a solid foundation of clinical practice in a Level III and/or IV NICU is

necessary before one assumes the advanced practice role of NNP. However, critical thinking skills

needed for the care of the critically ill neonate/newborn (birth to 28 days of life) can be derived in a

practice setting other than the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Therefore, while the majority of

experience should be in a Level III and/or IV NICU, practice experience in a critical (intensive

care) inpatient setting for infants (1 to 12 months of age) may be considered.

Anecdotal experience suggests that students with at least 2 years of clinical experience in the

neonatal intensive care setting are more successful in transitioning to the APRN role. Although it is

ideal for prospective students to complete their practice experience before beginning graduate

education, maintaining this position may not be feasible in today’s educational market. Appropriate

clinical experience in the care of critically ill newborns or infants is essential prior to beginning the

clinical component of an NNP program.

IV. Program Leadership

9

A. The director/coordinator of the NNP program must be a doctorally prepared,

nationally certified nurse practitioner. He or she has responsibility for overall

leadership of the program.

B. The faculty member who provides direct oversight of the neonatal-specific

program content must be a nationally certified NNP, preferably prepared at

the doctoral level.

C. The program faculty member must be prepared at the graduate level and must

maintain currency in clinical practice, licensure, and national certification as

an NNP. She or he is responsible for development of the NNP role and clinical

courses.

Elaboration

The program director/coordinator must be doctorally prepared, should have a strong foundation in

areas that support the responsibilities of leadership for the program (clinical knowledge, academic

leadership, administration, and scholarship), and must be nationally certified in a particular NP

population focus. She or he has academic oversight for the NNP program.

In programs with multiple tracks, although the program director/coordinator may be certified in

only one population-focused area of practice, she or he is responsible for leadership of all of the NP

tracks (National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 2016).

The faculty member with direct oversight of the NNP program must be a clinically experienced,

nationally certified NNP with a minimum of 2 years of NNP academic and/or clinical experience.

Doctoral preparation is preferable. She or he provides direct supervision for the NNP track;

provides curriculum oversight for the population-focused content of the NNP education program;

and participates in the identification, development, teaching, and evaluation of the population-

focused content for the advanced practice nursing core (advanced physiology and pathophysiology,

health assessment, and pharmacology). She or he may work in collaboration with the program

director/coordinator on the graduate nursing core (e.g., theory and research). This faculty member

is responsible for the selection, evaluation, and counseling of students in the program and also

participates in the ongoing evaluation of the program’s resources and services.

Members of the program faculty must be prepared at the required graduate level and must maintain

currency in clinical practice, licensure, and national certification as an NNP (AANP, 2013). These

faculty members are responsible for development of the NNP role and clinical courses, and one of

their primary responsibilities is the development, implementation, and evaluation of the NNP

program curriculum. They also should participate in the selection, evaluation, and counseling of

students and in the ongoing evaluation of the program’s resources and services.

Individuals providing didactic instruction should be drawn from the interprofessional team of

healthcare providers caring for infants and their families. Participants should be determined

according to the resources available to the program but should generally include NNPs,

neonatologists, pediatric subspecialists, APRNs, and allied health specialists. These faculty

members should have the “preparation, knowledge, and skills appropriate to their content areas”

(AANP, 2013). The didactic and clinical presentations of participating faculty will be tailored to

the individual needs of the students under the direction of the NNP faculty.

10

V. Curriculum

The curriculum must be designed to provide experiences, both didactically and

clinically, to meet the competencies as stated in the table on pages 19–39.

A. Didactic instruction

1. The curriculum must include three separate graduate-level core courses

in the following areas:

a. advanced physiology and pathophysiology, including general

principles that apply across the lifespan

b. advanced health assessment, including advanced assessment

techniques, concepts, and approaches specific to the neonatal

population

c. advanced pharmacology, including pharmacodynamics,

pharmacokinetics, and pharmacotherapeutics of all broad categories

of agents, including population-specific alterations in global concepts.

2. The curriculum must include a minimum of 200 didactic clock hours.

3. Specific neonatal content and/or courses related to advanced physiology

and pathophysiology, advanced health assessment, and advanced

pharmacology must be included and integrated throughout the other

neonatal-specific didactic and clinical courses.

B. Clinical instruction

1. The clinical component of the NNP curriculum must include a minimum

of 600 precepted clock hours with critically ill neonates or infants in the

delivery room and in Level II, III, and IV NICUs.

2. Precepted clock hours with neonates with surgical or cardiovascular

disease may occur in a pediatric ICU setting and may be included in the

minimum 600 hours.

3. While clinical experience in pediatric ICU and Level II NICUs caring

for critically ill newborns is valid, the majority of the 600 precepted

clock hours must be spent in Level III and IV NICUs.

4. Hours of observational experience may not be included in the minimum

600 hours.

5. Clinical skills, or simulation laboratory hours and clinical seminar

hours, may not be included in the minimum 600 hours.

11

6. Sufficient clinical experiences, including simulation in the care of NICU

graduate patients or long-term hospitalized infants must be included to

provide competency in the primary care component of the NNP scope of

practice. This is in addition to the 600 hours required in the care of

acute/critically ill neonates.

7. While it may be difficult to require a set number of deliveries that must

be attended or procedures that must be performed, attention to building

competence in these areas through clinical or simulation experiences

should be documented.

C. Core content

1. The curriculum must contain sufficient content to enable program

graduates to meet the core competencies and neonatal population-specific

competencies for NNP practice.

2. Recommended population-focused content for NNP education is outlined in

this document.

3. Formal NNP curriculum evaluation should occur at regular intervals.

4. Postgraduate students must successfully complete graduate didactic and

clinical requirements of an academic graduate NNP program through a

formal graduate-level certificate or degree-granting-graduate-level NNP

program. Postgraduate students are expected to master the same outcome

criteria as graduate-degree-granting-program NNP students.

Elaboration

The curriculum design of individual NNP programs is the prerogative of the program faculty.

Although NANN supports the program faculty’s exercise of creativity in designing the NNP

curriculum, it is essential that the curriculum plan meet all current standards, evaluation criteria,

and guidelines that have been iterated in this document. NNP faculty should have ongoing input

into the development and revision of curriculum, progression, and graduation criteria. To ensure

that students achieve successful program outcomes, program and course evaluation should be

ongoing and conducted in real time with formal curriculum overview at least every 5 years.

Not all facilities care for neonates with cardiac disease or post-surgically in the NICU; some

provide that care in the pediatric ICU (PICU). In this situation, precepted clinical hours caring for

such neonates in the PICU may count toward the minimum 600 clinical hours.

Use of Simulation in NNP education. Consistent with the most recent addition of the NTF

Criteria, the use of simulation as part of the NNP program curricula is encouraged, especially in

relation to high-risk/low-frequency situations (NONPF, 2016). However, it must be emphasized

that simulation experiences of any kind cannot be counted toward the required minimum number of

clinical hours (600) in direct patient care for NNP students.

12

The intended role of simulation as of 2017 in graduate nursing education is to augment, not

replace, direct patient care experiences. Examples of such experiences include laboratories for

procedures/skills and demonstration of advanced health assessment competencies. These

experiences may however, play a role in faculty evaluation of student performance, both formative

and summative, which are very valuable, particularly in distance-learning programs where direct

student observation by program faculty is limited.

Simulation can provide a creative space for faculty and students to enhance high-risk skills and

procedures in a safe environment for both students and patients. Additionally, simulation scenarios

can be developed in a uniquely advantageous fashion that both replicates the complex healthcare

environments in which NNPs practice and provides opportunities for integration of APRN

competency areas. For example, a simulation scenario ostensibly about “Patient Safety and Shift

Sign-Out” can easily serve to evaluate student performance related to Scientific Foundation,

Leadership, Quality, Healthcare Systems, etc. Through group simulations, students gain

competence and confidence, and enhance their communication skills. Interdisciplinary scenarios

also can be designed allowing students to work with other healthcare team members or students in

healthcare programs such as pharmacy, physical therapy, and undergraduate nursing programs.

(Faculty resources pertaining to simulation in nursing education are available via the National

League for Nursing’s Simulation Innovation Resource Center,

http://sirc.nln.org/mod/glossary/view.php?id=183.)

Despite the inability to substitute hours in simulation lab with direct patient care hours, the NONPF

recommends that advanced practice programs document their use of simulation as a teaching

strategy and clearly articulate the ways in which simulation is used to augment clinical experiences.

A sample form for this purpose is available in the NTF Criteria (2016) Appendix

(www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/Docs/EvalCriteria2016Final.pdf).

Clinical and didactic content related to primary care of the high-risk infant during the first 2 years

of life must be included in the curriculum. This content should be offered in addition to the clinical

and didactic hours required in the care of the high-risk neonate. This content provides necessary

preparation across the entire continuum of the NNP scope of practice. It also provides students with

a more holistic perspective on practice while enhancing role diversity and career opportunities.

NPs expanding into the NNP population-focused area of practice may be allowed to challenge

selected courses and experiences; however, didactic and clinical experiences must be sufficient to

allow the student to master the competencies and meet the criteria for national certification as an

NNP. NPs who have not practiced in the advanced practice role in an NICU must complete a

minimum of 600 clinical hours.

NPs currently practicing in the NICU who are not nationally certified in the neonatal population

focus must complete appropriate didactic coursework and a sufficient number of direct patient care

clinical hours to establish/demonstrate competency. Programs must document credit granted for

prior didactic and clinical experiences for individual students through a gap analysis. A gap

analysis should be completed for certified NNPs originally educated in a certificate program who

are completing a master’s degree

(www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/Docs/EvalCriteria2016Final.pdf).

13

VI. Preceptors and Clinical Sites

A. Preceptors

1. Preceptors for the 600 clock hours in the ICU must have their master of

science degree or doctoral degree in nursing (MS, MSN, or higher) and be

nationally certified as an NNP. Preceptors also may be physicians who are

board-certified in neonatology (or seeking board certification).

a. NNP preceptors must have a minimum of 1 year full-time equivalent

experience in the NP role, and have a minimum of 1-year full-time

equivalent employment at the clinical site. These requirements

ensure that the preceptor at a given site has both the clinical

expertise and the familiarity with the site necessary to provide

supervision of the NNP students.

2. The preceptor-to-student ratio should be such that individual learning

and evaluation are optimized. Therefore, the preceptor-to-student ratio

should not exceed 1:2.

3. Preceptors for other clinical experiences (e.g., in antenatal, intrapartum,

and primary care) must possess the clinical expertise necessary to

provide safe guidance and appropriate education for the NNP students.

4. Preceptors must be oriented to NNP program requirements and

expectations for supervision and evaluation of the NNP students.

5. Preceptors must be evaluated annually for the purpose of ensuring the

quality of the NNP students’ learning experiences and defining

preceptor relationships.

Elaboration

Each student should be assigned a primary preceptor to coordinate the clinical experience. For the

duration of the preceptorship, direct onsite supervision and consultation should be available from

the NNP or neonatologist preceptor. The preceptor-to-student ratio should be such that individual

learning is optimized. The recommended preceptor-to-student ratio may vary according to the

extent of clinical responsibilities for a patient caseload. The optimal preceptor-to-student ratio

differs if the preceptor also is seeing patients (1:1 if seeing own patients; 1:2 if not seeing own

patients). The NNP faculty, however, has ultimate responsibility for the supervision and evaluation

of students and for evaluation of the quality of the clinical learning environment (National Task

Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 2016).

Responsibilities of Clinical Preceptors

1. Meet with the student prior to the preceptorship to discuss clinical objectives, schedules,

and general guidelines. The preceptor should inform the student of any institutional

orientation requirements. These should be completed prior to the beginning of the clinical

experience.

14

2. Refer the student to any standardized procedures and management protocols applicable to

unit management.

3. Assign an initial caseload of patients. Expansion of the caseload will depend on the

evaluation of the student’s readiness, knowledge, and skill level.

4. Permit the student to perform all the required management activities for assigned patients

under appropriate supervision. These activities include, but are not limited to, the following:

a. Participating in resuscitation and stabilization of neonates in the delivery room

b. Admitting patients to the nursery, obtaining the perinatal and neonatal history,

performing physical examinations, developing the differential diagnosis, and

proposing the initial management plan

c. Providing ongoing management of infants in collaboration with the preceptor and

revising the management plan based on the evaluation of the infant’s progress

d. Performing diagnostic tests and procedures as dictated by the status and needs of the

patient

e. Responding to emergency situations to stabilize an infant

f. Documenting the infant’s clinical status, plan of care, and response to therapy in the

medical record

g. Evaluating the need for consultations and requesting them

h. Facilitating an understanding of the infant’s current and future healthcare needs and

providing support to parents and staff

i. Developing discharge plans

j. Participating in post-discharge primary care management

k. Participating in high-risk newborn transport if this service is available and if

permitted by hospital and school protocol

l. Providing staff development by participating in educational programs.

5. Provide direct supervision when the student is involved in patient care. The preceptor

should be available on site for ongoing consultation and evaluation of the care delivered

throughout the clinical experience.

6. Review the student’s documentation and make constructive suggestions for improvement.

7. Meet with the student on an ongoing basis to discuss specific learning objectives and

experiences. These meetings should focus on patient management and documentation,

successful completion of procedures, comprehension of pathophysiology and management,

interaction with staff and family, and role transition. Plans should be made for future

learning experiences to meet the student’s evolving learning needs. This information must

be communicated to the NNP faculty in a timely manner throughout the clinical

preceptorship.

8. Evaluate the student. The preceptor must communicate with the student and the faculty

member or program director. This should include written evaluation(s) of the student’s

performance furnished at specified intervals and upon completion of the preceptorship.

9. Contact the program director or appropriate faculty member in a timely fashion with

concerns or questions regarding the preceptor’s ability to fulfill responsibilities or if there

15

are problems concerning the student’s performance.

Responsibilities of Students

1. Discuss specific clinical objectives, schedules, and general guidelines with the preceptor

and faculty prior to the clinical rotation.

2. Provide the clinical site with the necessary documentation regarding licensure, health data,

liability insurance, and educational information (curriculum vitae or résumé).

3. Observe the policies of the clinical site.

4. Adhere to the standards and scope of professional practice.

5. Communicate with the preceptor and faculty on clinical progress and learning needs.

6. Demonstrate independent learning, diagnostic reasoning skills, and the use of available

resources.

7. Maintain and submit a log of clinical skills and activities.

8. Complete self-evaluations and evaluations of preceptor and clinical site as required.

9. Successfully complete the American Academy of Pediatrics/American Heart Association

Neonatal Resuscitation Program prior to beginning the clinical preceptorship.

B. Clinical sites

Clinical sites should be diverse and sufficient in number to ensure that core

curriculum guidelines can be observed and clinical objectives can be

accomplished.

1. Clinical sites should provide the student with the opportunity to manage

a caseload of newborns and infants so they have the experiences

necessary to achieve clinical competencies.

2. Clinical sites should provide the student with the opportunity to

participate in educational activities, attend high-risk deliveries, and

learn procedural skills.

3. Clinical sites should ensure that direct onsite supervision and

consultation are available from the preceptor.

4. Clinical sites should be evaluated annually to ensure the quality of the

NNP student’s learning experiences.

5. Faculty and student assessments of the clinical experience should be

conducted regularly and documented.

16

Elaboration

The NNP faculty or clinical coordinator is responsible for evaluating the ability of the potential

clinical sites to provide an optimal clinical experience for the student. During the clinical

preceptorship, the student has no legal status as a nurse practitioner and must be supervised by an

APRN or a physician experienced in the care of high-risk infants.

NNP program faculty should provide oversight of the clinical learning environment, which may

include, but is not limited to, physical and virtual site visits, e-mail, and phone consultations with

the preceptor and agency administrators, as well as the student’s appraisal of the clinical learning

environment. A mechanism should be in place to ensure the clinical setting provides the

opportunity to meet learning objectives and to document outcomes of the clinical experiences

(National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education, 2016).

Additional topics that may need to be addressed prior to the beginning of the clinical preceptorship

include liability insurance coverage, workers’ compensation benefits, contracts or agreements

between universities and clinical sites, and the relationship between the preceptor and the

university. These matters must be clarified because a wide variety of policies and practices exists.

In the case of distance-learning programs, interstate and international policies may need

elucidation.

Ideally, the clinical site would have established the NNP role description, advanced practice

procedures, and management protocols before the student’s clinical experience begins. However,

this may not be possible if the preceptorship takes place in an NICU where there are no practicing

NNPs. In this case the program director or faculty should be sure that this information is provided

to the student in the didactic portion of the program.

Responsibilities of Program Faculty

1. Develop clinical and didactic portions of the NNP program, as outlined in the section on

curriculum.

2. Provide the preceptor with the program objectives, outlines of didactic material, student’s

required reading list, and clinical course outline prior to the beginning of the clinical

rotation.

3. Develop an evaluation process and the necessary forms to be used for formative and

summative evaluation throughout and upon completion of the clinical preceptorship.

4. Consult with the student and preceptor to provide clarification of clinical objectives,

activities, specific individual responsibilities, and requirements.

5. Ensure that clinical site visits are conducted as outlined in NTF guidelines.

6. Give approval of the student’s clinical evaluation and competency throughout the program.

17

References

Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing. (2016). Accreditation manual. Section II

policies. Atlanta: GA: Author. Retrieved from www.acenursing.net/manuals/Policies.pdf.

American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. (2012). Policy Statement:

Levels of Neonatal Care. Pediatrics, 130 (3), 587-597.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2015). The doctor of nursing practice: current

issues and clarifying recommendations. Washington, DC: Author

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011). The essentials of master’s education in

nursing. Washington, DC: Author.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2006). The essentials of doctoral education for

advanced nursing practice. Washington, DC: Author.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2004b). Position statement on the practice

doctorate in nursing. Washington, DC: Author.

American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2013). Nurse Practitioner Curriculum. Austin, TX:

Author.

APRN Consensus Work Group & National Council of State Boards of Nursing APRN Advisory

Committee. (2008). APRN Joint Dialogue Group Report. Consensus model for APRN

regulation: Licensure, accreditation, certification, and education. Chicago, IL: National

Council of State Boards of Nursing. Retrieved from

www.ncsbn.org/7_23_08_Consensue_APRN_Final.pdf.

Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education. (2014). Procedures for accreditation of

baccalaureate and graduate degree nursing programs. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved

from www.aacn.nche.edu/ccne-accreditation/procedures.pdf.

National Association of Neonatal Nurse Practitioners. (2014). Competencies and Orientation

Toolkit for Neonatal Nurse Practitioners, 2

nd

ed., Chicago, IL: Author.

National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (2006). Domains and Core Competencies of

Nurse Practitioner Practice. Washington, DC: Author.

National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (2011; Amended 2012). Nurse Practitioner

Core Competencies. Washington, DC: Author.

National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (2013). Population-Focused Nurse

Practitioner Competencies. Washington, DC: Author.

National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practitioner Education. (2016). Criteria for evaluation of

nurse practitioner programs (5th ed.). Washington, DC: National Organization of Nurse

Practitioner Faculties.

18

Bibliography

Allan, J., Barwick, T. A., Cashman, S., Cawley, J. F., Day, C., Douglass, C. W., et al. (2004).

Clinical prevention and population health: Curriculum framework for health professions.

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(5), 471–476.

American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. (2013). Position statement on nurse practitioner

curriculum. Washington, DC: Author.

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ:

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Brown, S. J. (2005). Direct clinical practice. In A. B. Hamric, J. A. Spross, & C. M. Hanson (Eds.),

Advanced practice nursing: An integrative approach (3rd ed.) (pp. 143–185). Philadelphia:

Elsevier Saunders.

Donaldson, S., & Crowley, D. (1978). The discipline of nursing. Nursing Outlook, 26(2), 113–120.

Ehrenreich, B. (2002). The emergence of nursing as a political force. In D. Mason, D. Leavitt, &

M. Chaffee (Eds.), Policy and politics in nursing and health care (4th ed.) (pp. xxxii–

xxxvii). St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

Fawcett, J. (2005). Contemporary nursing knowledge: Analysis and evaluation of nursing models

and theories (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Davis.

Gortner, S. (1980). Nursing science in transition. Nursing Research, 29, 180–183.

Institute of Medicine. (2003). Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press.

National Association of Neonatal Nurses. (1997). Position statement on RN practice experience

and neonatal advanced nursing practice. Petaluma, CA: Author.

National Association of Neonatal Nurses. (2002a). Curriculum guidelines for neonatal nurse

practitioner (NNP) education programs. Glenview, IL: Author.

National Association of Neonatal Nurses. (2014). Education standards for neonatal nurse

practitioner (NNP) education programs. Glenview, IL: Author.

National Association of Neonatal Nurses. (2014). Sample forms and evaluation tools for neonatal

nurse practitioner (NNP) education programs. Glenview, IL: Author.

National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (1995). Advanced nursing practice:

Curriculum guidelines and program standards for nurse practitioner education.

Washington, DC: Author.

19

National Panel for Critical Care Nurse Practitioner Competencies. (2004). Critical care nurse

practitioner competencies. Washington, DC: National Organization of Nurse Practitioner

Faculties.

O’Neil, E. H., & Pew Health Professions Commission. (1998). Recreating health professional

practice for a new century: The fourth report of the Pew Health Professions Commission.

San Francisco: Pew Health Professions Commission.

Spross, J. A. (2005). Expert coaching and guidance. In A. B. Hamric, J. A. Spross, & C. M. Hanson

(Eds.), Advanced practice nursing: An integrative approach (3rd ed.) (pp. 187–223).

Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). Healthy people 2010. McLean, VA:

International Medical Publishing.

19

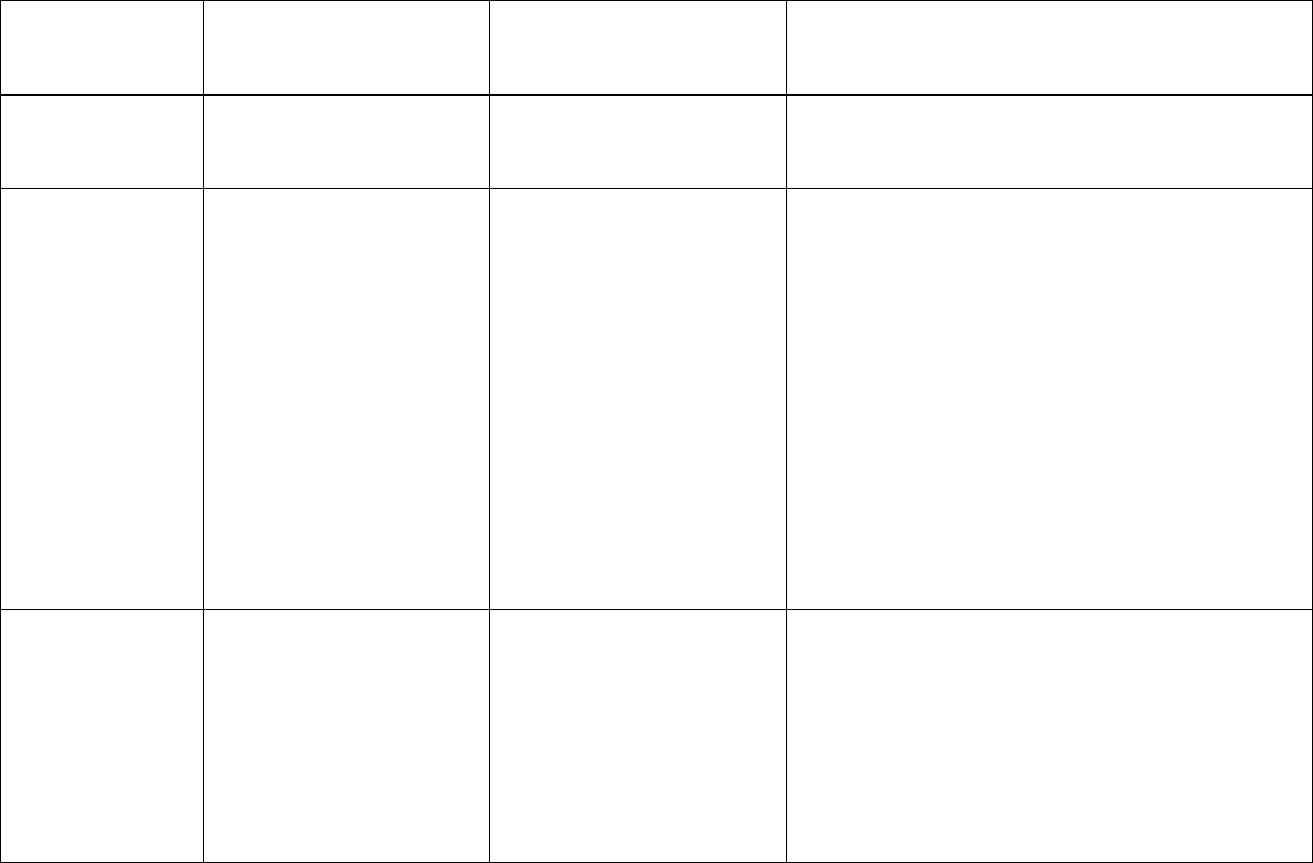

Competencies

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

Scientific

Foundation

Competencies

1. Critically analyzes data

and evidence for

improving advanced

nursing practice.

2. Integrates knowledge

from the humanities

and sciences within the

context of nursing

science.

3. Translates research and

other forms of knowledge

to improve practice

processes and outcomes.

4. Develops new practice

approaches based on the

integration of research,

theory, and practice

knowledge.

Advanced Neonatal Pathophysiology

Advanced Neonatal Pharmacology

Advanced Neonatal Assessment

Research and Quality Improvement

A. Research process and methods

B. Information databases

C. Critical evaluation of research findings

D. Translational research

E. Research on vulnerable populations

F. Funding for research

G. Research dissemination

H. Institutional review boards

I. Safety

J. Continuous Quality Improvement

Professional Role

A. Nursing theories

B. Evidence-based practice

Leadership

Competencies

1. Assumes complex and

advanced leadership

roles to initiate and guide

change.

2. Provides leadership to

foster collaboration with

multiple stakeholders (e.g.,

patients, community,

integrated healthcare

teams, and policy makers)

to improve health care.

Interprets the role of the

NNP to the infant’s family,

other healthcare

professionals, and the

community.

Professional Role

A. Professional leadership

B. Professional accountability/ethical standards of practice

C. Evidence-based practice

D. Role theory

E. Advanced practice role

F. Role of the NNP

G. Scope of practice for the NNP

H. Standards of practice

I. Professional regulation and licensure

J. Credentialing and certification

20

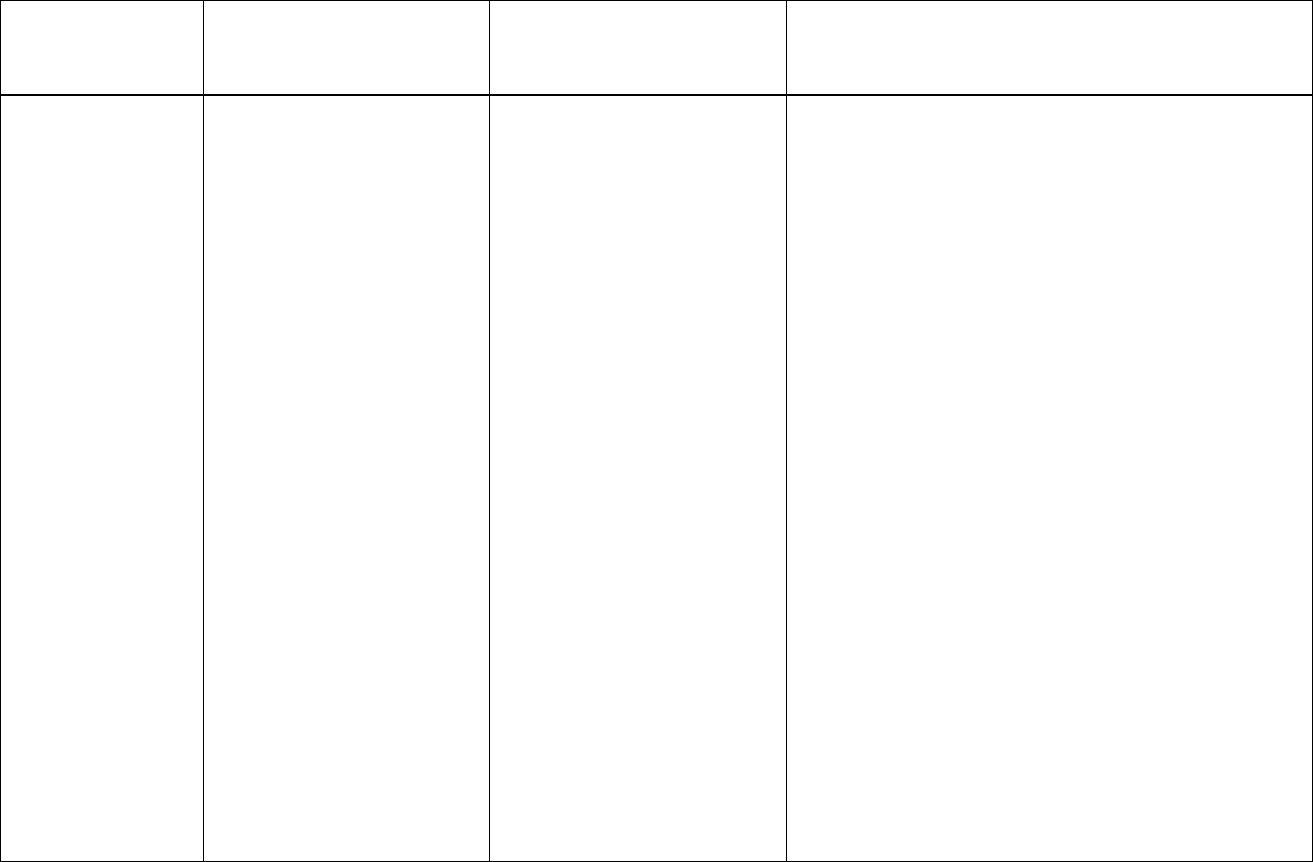

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

3.

Demonstrates

leadership that uses

critical and reflective

thinking.

4.

Advocates for improved

access, quality, and cost

effective health care.

5.

Advances practice through

the development and

implementation of

innovations incorporating

principles of change.

6.

Communicates practice

knowledge effectively both

orally and in writing.

7.

Participates in professional

organizations and activities

that influence advanced

practice nursing and/or

health outcomes of a

population focus.

K. Clinical decision making and problem solving

L. Professional scholarship

Teaching and Education

A. Theories—motivational, change, education,

communication

B. Program planning and evaluation

C. Instructional technology

D. Cultural sensitivity

E. Communication

F. Collaboration

G. Conflict resolution

H. Assertiveness

I. Collaborative practice models

J. Informatics

K. Consultation

Quality

Competencies

1. Uses best available

evidence to continuously

improve quality of

clinical practice.

2. Evaluates the relationships

among access, cost,

quality, and safety and their

influence on health care.

3. Evaluates how

Healthcare Policy and Advocacy

A. Economics of health care

Research and Quality Improvement

A. Information databases

B. Critical evaluation of research findings

C. Translational research

D. Research dissemination

21

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

organizational structure,

care processes,

financing, marketing,

and policy decisions

impact the quality of

health care.

4. Applies skills in peer

review to promote a

culture of excellence.

5. Anticipates variations in

practice and is proactive

in implementing

interventions to ensure

quality.

E.

Institutional review boards

F.

Safety

G.

Continuous quality improvement

H.

Finance and value-added care

Practice Inquiry

Competencies

1. Provides leadership in the

translation of new

knowledge into practice.

2. Generates knowledge from

clinical practice to improve

practice and patient

outcomes.

3. Applies clinical

investigative skills to

improve health outcomes.

A. Research process and methods

B. Information databases

C. Critical evaluation of research findings

D. Translational research

E. Research on vulnerable populations

F. Research dissemination

G. Institutional review boards

H. Safety

I. Continuous Quality Improvement

Technology and

Information Literacy

Competencies

1. Integrates appropriate

technologies for

knowledge management to

improve health care.

2. Translates technical and

Determines the health literacy

needs of infant’s family in

planning care

Communication

A. Communication theory

B. Collaboration

C. Conflict resolution

22

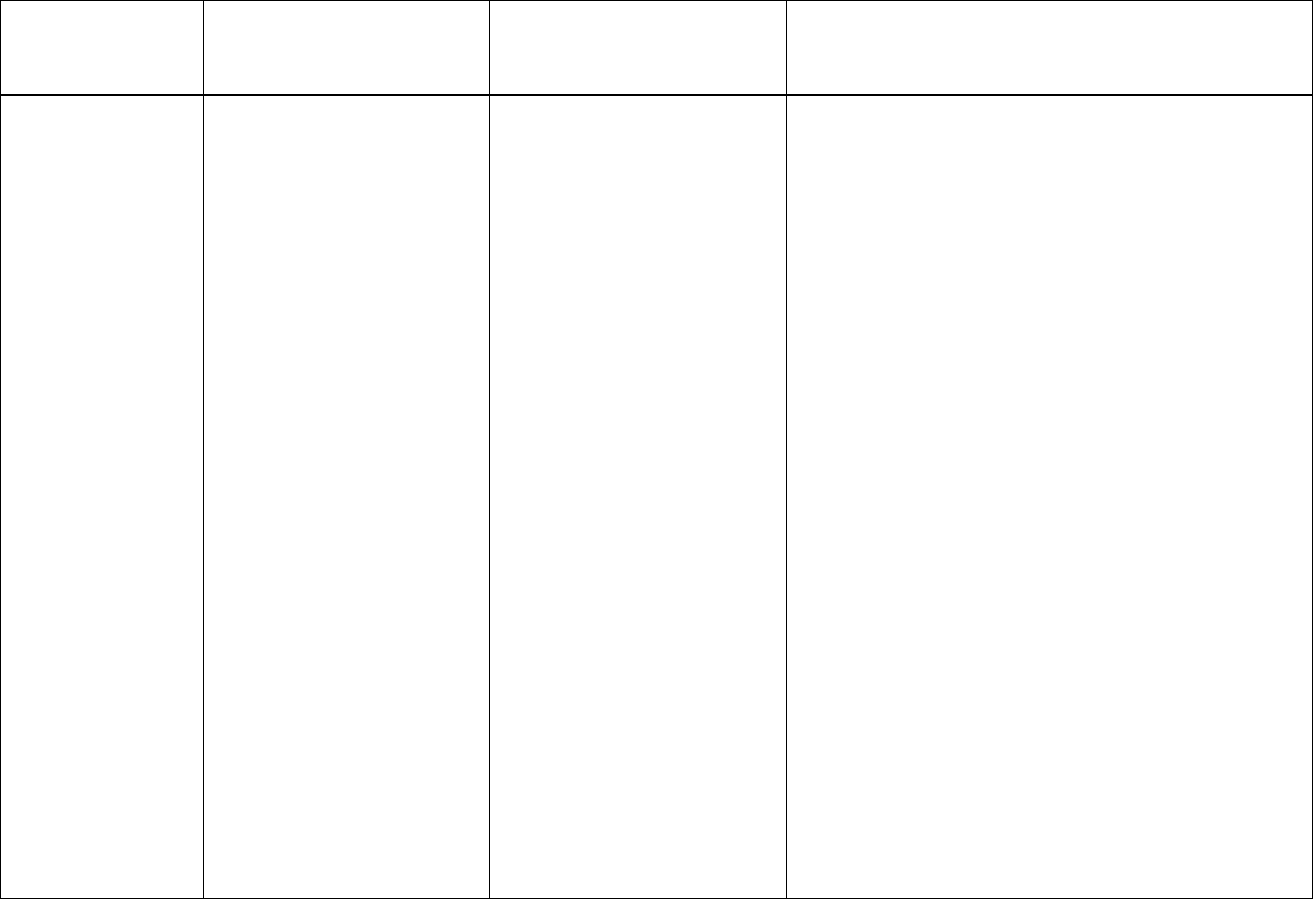

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

scientific health information

appropriate for various

users’ needs.

2a. Assesses the patient’s

and caregiver’s

educational needs to

provide effective,

personalized health

care.

2b. Coaches the patient

and caregiver for

positive behavioral

change.

3. Demonstrates information

literacy skills in complex

decision making.

4. Contributes to the design

of clinical information

systems that promote safe,

quality, and cost-effective

care.

5. Uses technology systems

that capture data on

variables for the evaluation

of nursing care.

D. Assertiveness

E. Collaborative practice models

F. Informatics

G. Information data bases/technology

H. Consultation

I. Health literacy

Professional Role

A. Information technology

B. Professional boundaries

Teaching and Education

A. Theories—motivational, change, education,

communication

B. Program planning and evaluation

C. Instructional technology

D. Cultural sensitivity

Policy

Competencies

1. Demonstrates an

understanding of the

interdependence of policy

and practice.

2. Advocates for ethical

Healthcare Policy and Advocacy

A. Process of healthcare legislation/administrative policy

B. Maternal and child health legislation

C. Implications of healthcare policy

D. Economics of health care

23

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

policies that promote

access, equity, quality,

and cost.

3. Analyzes ethical, legal,

and social factors

influencing policy

development.

4. Contributes to the

development of health

policy.

5. Analyzes the implications of

health policy across

disciplines.

6. Evaluates the impact of

globalization on healthcare

policy development.

E. Healthcare financing

F. Legislation and regulations concerning advanced

practice

G. Advocacy

Ethical and Legal Issues

A. Ethical decision making

B. Ethical issues—reproductive, prenatal, neonatal, and

infancy

C. Ethical use of information

D. Patient advocacy

E. Resource allocation

F. Legal issues affecting patient care and professional

practice

G. Cultural sensitivity

Global Health Care

Communication

A. Communication theory

B. Collaboration

C. Conflict resolution

D. Assertiveness

E. Collaborative practice models

F. Informatics

G. Consultation

Health Delivery

System

Competencies

1. Applies knowledge of

organizational

practices and

complex systems to

1. Advocates for quality patient

care.

2. Assists families in dealing

with system complexities.

Management and Organization

A. Organizational theory

B. Principles of management

C. Models of planned change

24

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

improve healthcare

delivery.

2. Effects health care

change using broad-

based skills, including

negotiating, consensus-

building, and partnering.

3. Minimizes risk to

patients and providers

at the individual and

systems level.

4. Facilitates the

development of

healthcare systems that

address the needs of

culturally diverse

populations, providers,

and other stakeholders.

5. Evaluates the impact of

healthcare delivery on

patients, providers, other

stakeholders, and the

environment.

6. Analyzes organizational

structure, functions, and

resources to improve the

delivery of care.

7. Collaborates in planning

for transitions across the

continuum of care.

D. Collaborative practice

E. Healthcare system financing

F. Billing and coding for reimbursement

G. Standards of practice

H. Cost, quality, and outcome measures

I. Resource management

J. Evaluation models

K. Peer review

Communication

A. Communication theory

B. Collaboration

C. Conflict resolution

D. Assertiveness

E. Collaborative practice models

F. Informatics

G. Consultation

Healthcare Policy and Advocacy

A. Process of healthcare legislation

B. Maternal and child health legislation

C. Implications of healthcare policy

D. Economics of health care

E. Third-party reimbursement

F. Legislation and regulations concerning advanced

practice

G. Advocacy

25

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

Research and Quality Improvement

A. Safety

B. Continuous Quality Improvement

Ethics

Competencies

1. Integrates ethical

principles in decision

making.

2. Evaluates the ethical

consequences of

decisions.

3. Applies ethically sound

solutions to complex

issues related to

individuals, populations

and systems of care.

Conforms to the Code of Ethics of

the National Association of

Neonatal Nurses.

Ethical and Legal Issues

A. Ethical decision making

B. Ethical issues—reproductive, prenatal, neonatal, and

infancy

C. Ethical use of information

D. Patient advocacy

E. Bioethics committees

F. Clinical research

G. Resource allocation

H. Genetic counseling

I. Legal issues affecting patient care and professional

practice

J. Informed consent

K. Cultural sensitivity

L. Palliative care

M. End-of-life care

Independent

Practice

Competencies

1. Functions as a licensed

independent practitioner.

2. Demonstrates the highest

level of accountability for

professional practice.

3. Practices independently

managing previously

diagnosed and

undiagnosed patients.

3a. Provides the full

1. Obtains a thorough health

history to include maternal

medical, antepartum,

intrapartum, newborn, and

interim history.

2. Performs a complete,

systems-focused

examination to include

physical, behavioral, and

developmental

Advanced Neonatal Pathophysiology

Advanced Neonatal Pharmacology

Advanced Neonatal Assessment

Perinatal Issues

A. Perinatal physiology

1. Maternal physiology (physiologic adaptation to

pregnancy, pathologic changes or disease in

pregnancy, effects of pre-existing disease)

2. Fetal physiology

26

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

spectrum of

healthcare services

to include health

promotion, disease

prevention, health

protection,

anticipatory

guidance,

counseling, disease

management, and

palliative and end-of-

life care.

3b. Uses advanced

health assessment

skills to differentiate

between normal,

variations of normal

and abnormal

findings.

3c. Employs screening

and diagnostic

strategies in the

development of

diagnoses.

3d. Prescribes

medications within

scope of practice.

3e. Manages the

health/illness status

of patients and

families over time.

4. Provides patient-centered

assessments.

3. Develops a comprehensive

database that includes

pertinent history, diagnostic

tests, and physical and

developmental

assessment.

4. Demonstrates critical

thinking and diagnostic

reasoning skills in clinical

decision making.

5. Establishes priorities of

care.

6. Initiates therapeutic

interventions according to

established standards of

care.

7. Demonstrates competency

in the technical skills

considered essential for

NNP practice according to

the standards set forth by

national, professional

organizations.

8. Intervenes according to

established standards of

care to resuscitate and

stabilize compromised

newborns and infants.

9. Implements

developmentally

appropriate care.

3. Transitional changes

4. Neonatal physiology

5. Immune and nonimmune hydrops

B.

Pharmacology

1.

Principles of pharmacology and

pharmacotherapeutics, including those at the cellular

response level

2. Principles of pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics of broad categories of drugs

3. Common categories of drugs used in the newborn

and infant

4. Monitoring of drug therapies including drug levels

when appropriate

5. Effects of drugs during pregnancy and lactation

C. Genetics

1. Molecular genetic testing

2. Genetic screening

3. Specific chromosomal defects and management

4. Human genome project

5. Gene mapping and personalized care

6. Genetic counseling

General Assessment

A. Perinatal history

B. Antepartum conditions

C. Prenatal diagnostic testing

D. Intrapartum conditions

E. Influence of NICU environment on the newborn and

infant

F. Gestational age assessment

G. Physical assessment

H. Behavioral assessment

27

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

care recognizing cultural

diversity and the patient

or designee as a full

partner in decision

making.

4a. Works to establish a

relationship with the

patient characterized

by mutual respect,

empathy, and

collaboration.

4b. Creates a climate of

patient-centered

care to include

confidentiality,

privacy, comfort,

emotional support,

mutual trust, and

respect.

4c. Incorporates the

patient’s cultural and

spiritual preferences,

values, and beliefs

into health care.

4d. Preserves the

patient’s control over

decision making by

negotiating a

mutually acceptable

plan of care.

10. Ensures that principles of

pain management are

applied to all aspects of

neonatal and infant care.

11. Documents assessment,

plan, interventions, and

outcomes of care.

12. Considers community and

family resources and

strengths, when planning

patient care and follow up

needs across the

continuum of care.

13. Communicates with family

members and caregivers

regarding the newborn and

infant’s healthcare status

and needs.

14. Applies principles of crisis

management to assist

family members in coping

with their infant’s illness.

15. Participates in the learning

needs of students and

other healthcare

professionals.

16. Participates as a member

of an interdisciplinary team

through the development of

collaborative and

innovative practices.

17. Identifies strategies to

I. Developmental assessment

J. Growth and nutritional assessment

K. Immunization assessment

L. Pain assessment and evidence-based tools across the

population (up through 2 years)

M. Assessment of family adaptation, coping skills, and

resources

Sociocultural Assessment

A. Family assessment

1. Family function

a. Roles

b. Interactions

c. Effect of childbearing

2. Social, cultural, and spiritual variations

3. Support systems

B. Families in crisis

1. Crisis theory

2. Principles of intervention

3. Crises of childbearing

a. Sick or premature infant

b. Chronically ill or malformed infant

c. Death of an infant

4. Grief

a. Stages

b. Factors influencing grieving process

c. Pathologic grief

d. Sibling reactions

C. Principles of family-centered care

Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Assessments

A. Clinical laboratory tests

1. Microbiologic

2. Biochemical

3. Hematologic

28

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

deliver culturally sensitive,

high-quality care free of

personal biases.

18. Applies principles of

neonatal

pharmacotherapeutics to

clinical practice.

4. Serologic

5. Metabolic and endocrine

6. Immunologic

7. Routine newborn screening

8. Other

B. Diagnostic tests (types and techniques)

1. Ultrasound

2. Computed tomography (CT)

3. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic

resonance angiogram (MRA), magnetic resonance

spectroscopy (MRS)

4. X ray

5. Fluoroscopy

6. Electrocardiogram (EKG)

7. Electroencephalogram (EEG)

8. Echocardiogram (ECHO)

9. Cardiac catheterization

C. Selection of diagnostic tests

1. Indications

2. Reliability

3. Advantages and disadvantages

4. Cost-effectiveness

5. Interpretation of results

D. Performance of procedures for neonates and infants,

including but not limited to:

1. Lumbar puncture

2. Umbilical vessel catheterization

3. Percutaneous arterial and venous catheters

4. Arterial puncture

5. Venipuncture

6. Capillary heel-stick blood sampling

7. Suprapubic bladder aspiration

29

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

8. Bladder catheterization

9. Endotracheal intubation

10. Laryngeal airway placement

11. Intraosseous

12. Needle aspiration of pneumothorax

13. Chest-tube insertion and removal

14. Exchange transfusion

15. Replacement of g-tube

There may be procedures not covered in an NNP program but

that are part of the NNP scope of practice that the NNP

graduate would be allowed to perform if credentialed by the

facility. These may include:

A.

Circumcision

B.

Pericardial tap

C.

Ventricular tap

D.

Superficial suturing

E.

Removal of skin tags or extra digits by suture ligation

General Management (across the population, from neonate

through age 2)

A. Thermoregulation

1. Factors affecting heat loss and production

2. Mechanisms of heat loss and gain

B. Resuscitation and stabilization

1. Assessment of risk factors

2. Physiology of asphyxia

3. Indications for intubation, ventilation, and cardiac

compressions (see also section on neonatal

procedures)

4. Resuscitation equipment

5. Pharmacotherapeutics

6. Stabilization

30

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

7. Neonatal transport

8. Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) provider

9. Therapeutic hypothermia

C. Pain management

1. Physiology of pain

2. Pain management

a. Nonpharmacologic

b. Pharmacologic

D. Palliative and end-of-life care

1. Ethical considerations

2. Pain management at end of life

3. Hospice care

4. Bereavement

Clinical Management

A. Cardiovascular system

1. Embryology

2. Physiology/pathophysiology

3. Fetal, transitional, neonatal circulation

4. Rhythm disturbances/EKG interpretation

5. Myocardial dysfunction

6. Shock, hypotension, hypertension

7. Congenital heart disease (pathophysiology, clinical

presentation, differential diagnosis, medical

management, pre- and postoperative management)

8. Cardiovascular radiology and

echocardiogram interpretation

9. Pharmacotherapeutics

B. Pulmonary system

1. Embryology and pulmonary development after birth

2. Physiology (oxygenation and ventilation, gas

exchange, acid-base balance)

31

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

3.

Pathophysiology

4.

Asphyxia

5.

Pulmonary diseases (pathophysiology, etiology,

clinical presentation, differential diagnosis,

treatment)

6.

Pulmonary radiology

7.

Respiratory therapy

a. Physiologic principles

b. Physiologic monitoring

c. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

d. Ventilation strategies

e. Extracorporeal membrane

oxygenation (ECMO)

8.

Pharmacotherapeutics

C. Gastrointestinal (GI) system

1. Embryology

2. Anatomy and physiology of the GI tract

a. Structure and function

b. Hormonal influence

c. Motility

d. Digestion and absorption

3. Pathophysiology

4. Digestive and absorptive disorders

a. Disorders of sucking and swallowing

b. Motility

c. Gastroesophageal (GE) reflux

d. Malabsorption

e. Diarrhea

f. Short gut

5. Anomalies and obstruction

6. Necrotizing enterocolitis

7. Spontaneous intestinal perforation

8. Pharmacotherapeutics

32

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

D. Nutrition

1. Effects of maturational changes on management of

nutritional requirements and feeding

2. Caloric and nutritional requirements and calculations

3. Feeding methods

a. Breast

b. Bottle

c. Gavage

d. Gastrostomy

e. Transpyloric

f. Trophic

4. Human milk versus formula

a. Composition

b. Benefits

c. Preterm infants

d. Human milk fortifier

e. Donor human milk and exclusive human milk

diets

5. Parenteral nutrition

a. Composition

b. Indications

c. Benefits

d. Complications

e. Monitoring

6. Dietary supplementation for term and preterm

infants

7. Dietary adjustments in special circumstances

a. Cholestasis

b. Short gut syndrome

c. Osteopenia

d. Inborn errors of metabolism

e. Vitamin deficiencies and associated features,

signs and symptoms

f. Congenital heart disease

33

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

g. Chronic lung disease

E. Renal and genitourinary

1. Embryology and anatomy

2. Renal physiology

3. Pathophysiology

4. Evaluation of renal function

5. Urinary tract infections

6. Congenital anomalies

7. Functional abnormalities of the renal system

8. Renal failure

a. Predisposing factors and etiologies

b. Pathophysiology

c. Management

Fluid and electrolytes

Nutritional modification

Drug modification

Hemofiltration

Dialysis

Transplant

Pharmacotherapeutics

F. Fluid and electrolytes

1. Physiology

a. Electrolyte homeostasis

b. Body composition in fetal and neonatal

periods

c. Transitional changes

d. Insensible water loss

e. Endocrine control, mineralocorticoids,

antidiuretic hormone (ADH),

calcitonin/parathyroid hormone (PTH)

f. Renal function/physiology

34

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

2. Pathophysiology

3. Principles of fluid therapy

a. Assessment of hydration

b. Maintenance requirements

c. Factors affecting total fluid

requirements

4. Disorders of fluids and electrolytes

5. Vomiting and dehydration

G. Endocrine and metabolic system

1. Neuroendocrine regulation

2. Carbohydrate/fat/protein metabolism

a. Inborn errors

3. Infant of a diabetic mother

4. Pathophysiology

5. Hypothalamic-Pituitary axis function and disorders

a. Adrenal gland (embryology, pathways,

and tests)

b. Thyroid (embryology, pathways and tests,

management)

c. Calcium and phosphorus homeostasis

d. Inborn errors of metabolism

e. Newborn screening

f. Ambiguous genitalia, intersex disorders

g. Pharmacotherapeutics

H. Hematologic system and malignancies

1. Development of the hematopoietic system

2. Physiology/pathophysiology

3. Anemia

4. Polycythemia and hyperviscosity

5. Bilirubin

a. Physiology of bilirubin production, metabolism,

and excretion

b. Hyperbilirubinemia

c. Breast milk jaundice

d. Encephalopathy

35

Competency Area

NP Core Competencies

Neonatal NP Competencies

Curriculum Content to Support

Competencies

Neither required nor comprehensive, this list reflects only suggested content

specific to the population

6. Hepatic disorders

7. Coagulation and platelets

8. Disorders of coagulation and platelets

I. Immunologic system

1. Development of the immune system

2. Function of the immune system

3. Allo- and auto-immune disorders

4. Pharmacotherapeutics

J. Infectious diseases

1. Physiology/Pathophysiology

2. Evaluation of the infant

a. History

b. Physical examination

c. Laboratory data

d. Other diagnostic tests

3. Treatment

a. Antimicrobial

b. Adjunctive therapy

c. Immunizations

d. Biologic therapies

4. Infection with specific microorganisms

5. Maternal infections

6. Systemic Inflammatory Response System (SIRS)

7. Pharmacotherapeutics

K. Musculoskeletal system

1. Embryology

2. Congenital abnormalities

3. Birth injuries