Fair & Equitable • June 2013

3

N

ew Mexico has 33 counties, all at various levels of

automation and geographic information system

(GIS) adoption. The New Mexico Taxation and

Revenue Department (TRD), via its Property Tax Division

(PTD), provides the local county assessment community

with GIS and data automation support to encourage the

use of automated mapping and to apply standards for data

collection and processing.

There are many business drivers for the statewide aggre-

gation and standardization of parcel data—the relatively

recent New Mexico Broadband Program (an initiative

aimed at defining broadband availability and enhancing

its adoption), wildland fire response support, public safety,

and enhanced property information are some of the most

visible. The cooperation among and support of the state

agencies that collect, aggregate, consume, and publish

geospatial data have made it possible for many programs

to benefit from the efforts of GIS-related programs.

Project History

In 2006 the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC)

Cadastral Subcommittee was funded by the Office of

Wildland Fire of the U.S. Department of the Interior to

assemble and standardize available digital parcel data

within wildland fire hazard areas. The U.S. Forest Service

and Department of Interior wildland fire groups had pre-

viously determined wildland fire modeling could be used

in conjunction with mapped structure location points to

determine from a planning perspective how and where

to deploy resources to fight the fire. The locally collected

and maintained parcel data were identified as the most

current and reliable source for structure locations on pri-

vately owned lands.

The first collection of parcel data for this effort in New

Mexico, in 2007, was a very labor-intensive process. Each

county was individually called or visited, and the wildland

fire project goals and data needs were explained. The

benefits of the data sharing were explained by using the

experiences from Montana. Because the parcel data from

New Mexico had not been used in fire response, no local

examples were possible.

Almost half of the state was covered in that first year. Lo-

cal data were aggregated, and information on structure

locations was extracted to create a structure point file that

could be viewed in the Wildland Fire Decision Support

System (WFDSS).

In 2008 the data collection and aggregation became

easier. The counties were now familiar with the wildland

fire uses, and TRD/PTD’s role in the effort was better un-

derstood. TRD/PTD sent a letter to each county assessor

in January 2008 requesting that available parcel data be

provided to TRD, which would then standardize the data

and provide it to the Wildland Fire Program. The stan-

dardization of the locally provided data was not done in

the 2007 collection, so this processing was an added step.

The statements made or opinions expressed by authors in Fair & Equitable do not necessarily represent a policy position of the

International Association of Assessing Officers.

New Mexico Statewide Parcel Data

Larry Brotman, Nancy von Meyer, Ph.D., and Sharon Schiebold

Photo courtesy of MarbleStreetStudio.com

4

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

In the 2008 collection effort parcel polygons were used

if they were available. In a few of the high-hazard areas,

site address points from the 911 systems were used as a

surrogate to locate structure points. These locally provided

address locations were produced by the state’s Enhanced

911 (E-911) Program/Rural Addressing Program and

were used in only a few counties. The address data were

not widely available in 2008. The resulting data delivery

was a mix of parcel information and structure locations

and is summarized in figure 1.

In 2010 and 2011 the structure locations were updated

from the site address points only. As a function of the E-911

Program of the Department of Finance and Administra-

tion (DFA), most of the state’s counties have been using

a GIS-based application to map road centerlines, assign

site addresses, and create point features to represent loca-

tions for emergency dispatch purposes. From a Wildland

Fire Program perspective, TRD and the subcommittee’s

interest in this program was piqued when it learned of

Lincoln County’s use of an E-911/rural addressing exten-

sion that allows assessor parcel attributes to be stored with

address points and their respective data. Again, as the use

of WFDSS has been refined, integrating the address points

so diligently developed by counties for rural addressing

and E-911 may prove to be very beneficial when digital

parcel polygons are not available or are in a format sup-

portive of the application. Although supplemented with

data developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), this

concept was illustrated during the Trigo Fire.

The Trigo Fire

In April 2008 the Trigo Fire broke out between Torrance

and Valencia counties in the Manzano Mountains of cen-

tral New Mexico.

Using a combination of imagery, which is analyzed to

find color and signal characteristics of rooftops and man-

made structures, the USGS developed an initial inventory

of possible structure locations. In Valencia County parcel

data and assessment information, which indicate which

parcels had structures data, was combined with the imag-

ery results to verify the structure locations (see figure 2).

In some cases the imagery found structures that were not

on the tax roll; these structures were primarily either un-

der construction or ancient structures in Native American

country that were not on the tax roll. The image analysis

and parcel data assisted in identifying multiple structures

on the same parcel, generally indicating outbuildings or

agricultural use buildings. This information was of great

assistance to the fire response planning. Using this com-

bination of data proved that applying both a site address

inventory and the parcel data provided the most complete

effective solution to support wildland fire response plan-

ning.

Collaboration among personnel at Torrance County,

Valencia County, the U.S. Forest Service, the USGS, the

subcommittee, and TRD clearly demonstrated the benefits

derived from multi-jurisdictional collaboration in planning

Feature Article

Figure 1. Collection status in 2009

Figure 2. Extent of Trigo fire

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

5

for and responding to potentially catastrophic fire events.

The Little Bear Fire

Another key event occurred on June 4, 2012 when a light-

ning strike set off a wildland fire in Lincoln County, New

Mexico, in the White Mountain Wilderness area. Because

of available fuel and dry conditions, the fire spread quickly.

By the time the fire was fully contained, approximately

44,000 acres were involved. Figure 3 shows the final fire

perimeter in light red shading.

By using the WFDSS and parcel data from New Mexico,

an estimated 371 structures within the fire perimeter were

located, and slightly more than 12,000 structures in the

fire response planning area were involved. Post-fire analy-

sis determined that more than 250 homes and structures

were destroyed, making the Little Bear Fire one of the

most destructive fires in New Mexico’s history. The Fed-

eral Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided

more than $1 million to reimburse the county for costs

incurred from cleanup and response (http://www.kob.

com/article/stories/s2960949.shtml and http://www.to-

mudall.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=1239).

The State Department of Homeland Security and Emer-

gency Management’s experience with the Little Bear Fire

in Lincoln County raised the awareness of the importance

of assessor parcel data, preferably in a standardized form.

The parcel data were recognized as an essential compo-

nent in working with federal entities such as FEMA to as-

sign value to property loss. The attribute richness of the

parcel data added more value to the structure locations

than the site address points alone.

2012 Data Collection and Standardization

While the site address points used in 2010 and 2011 did

provide an inventory of structure locations, information

on the structure or parcel use, the values and owner type

(public, private) were needed to further support wildland

fire response and cleanup. The effort that began in 2007

was renewed in 2012 with the collection and standardiza-

tion of the parcel mapping data.

A first step in this process was to finalize the state parcel

data standard for the aggregated parcel data. The table at

the end of this article lists the finalized New Mexico Parcel

Data Standard. This is a format for the counties to provide

parcel data to the New Mexico TRD/PTD or for TRD to

transform data provided by the counties. The goal of this

standard is the assembly and aggregation of the varying

county data into a common format that can be used for

analysis and display. This standard builds on the national

parcel publication standard, adding attributes specific to

New Mexico.

Mapping from the Property Identifier

A few New Mexico counties do not have GIS real property

parcel features, either as polygons or points, to represent

data contained within their property valuation or mass ap-

praisal systems. Many counties have computer-aided map-

ping, which does provide a computer-based map, but this

mapping cannot be readily linked to database attributes

from the computer-assisted mass appraisal (CAMA) sys-

tem. Often the computer-aided drafting (CAD) mapping

organizes the parcel maps into map sheet tiles, further

complicating the ability to combine the data into a single

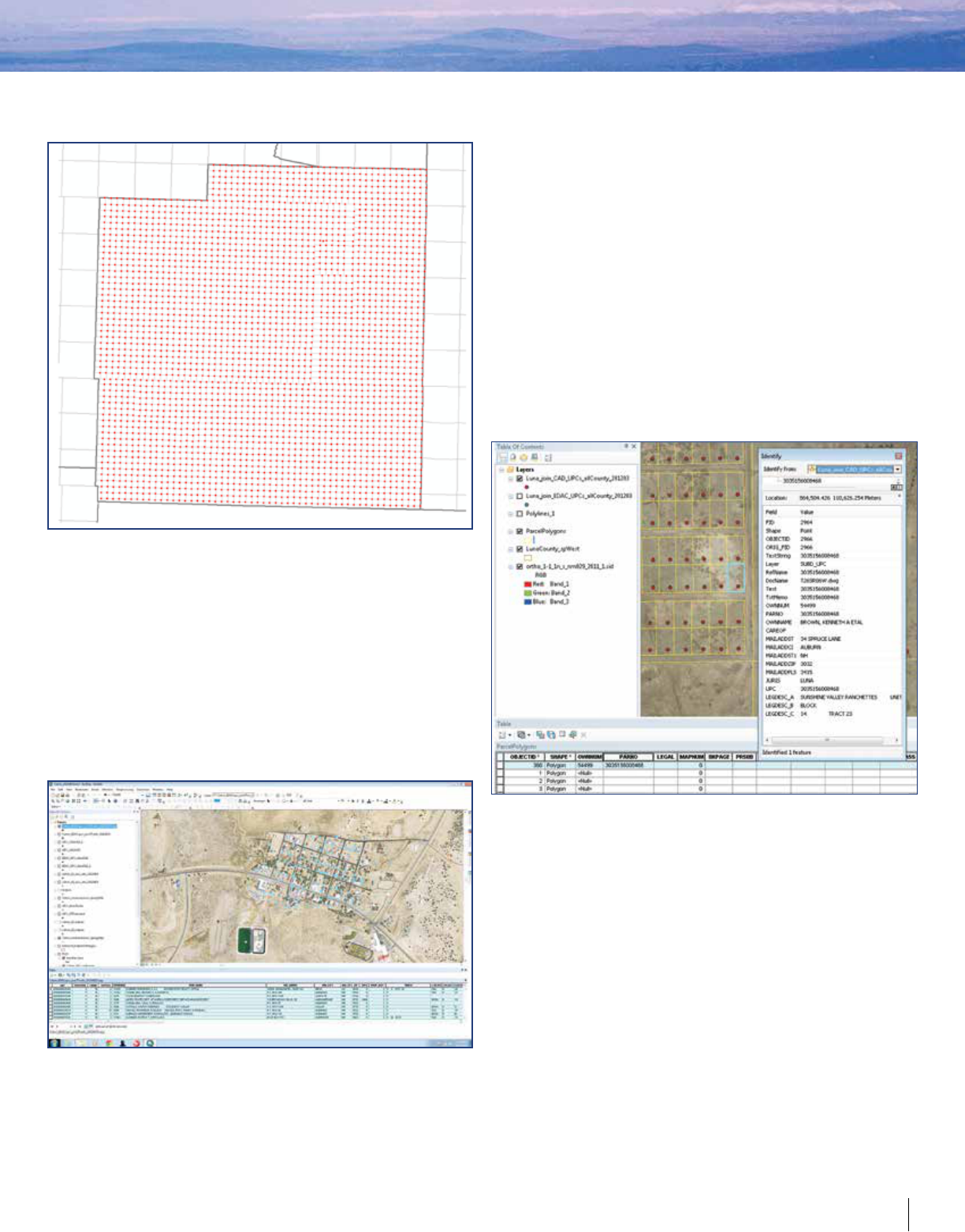

database or a statewide data set. Figure 4 illustrates the

mapping technology used by the New Mexico counties.

At the very least, having GIS point features and their re-

spective data attributes represent parcels in the assessor’s

database can be highly beneficial to supporting data shar-

ing with entities concerned with public safety, asset and

property protection, and access to utility, transportation,

and communication (broadband) infrastructure.

With funding provided by the New Mexico Broadband

Program, three New Mexico counties, the TRD, and the

University of New Mexico’s Earth Data Analysis Center

(EDAC) have collaborated to develop a method that

geocodes the Uniform Property Code (UPC) assigned by

New Mexico county assessors to each property contained

within their respective appraisal/valuation systems. The

UPC is created through a reference to the Public Land

Survey System (PLSS) and is location based.

The three counties outlined in red in figure 4 were se-

lected as a pilot project to test whether the UPC, as pre-

Figure 3. Perimeter of Little Bear Fire

6

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

Feature Article

scribed in the New Mexico Mapping Manual, could be

used to generate a point location for parcels. The follow-

ing three counties were selected for the reasons indicated:

• Catron County

– Very limited “digital” parcel data

– No way to “connect” assessor database with maps

• Luna County

– Digital parcels in CAD only with the UPCs as an-

notation.

– No connection between assessor database and maps

• Mora County

– GIS polygons 10+ years old and not maintained

since developed

– No connection between assessor database and maps.

The UPC is, by definition, tied to the PLSS section and

section division lines. The UPC identifies a source line

and provides an offset distance from the source line to

the parcel centroid; this is shown in figure 5.

To run the geocoding, the standardized PLSS data were

processed to support relating the PLSS data to the UPC.

The process for determining section reference points was

as follows:

1. Convert Second Division (1/16-th aliquot part and

government lot) corners to vertices. The standard-

ized PLSS data set, CadNSDI, was used as the source

for these data.

2. Identify the vertex nearest to the prime meridian–

baseline intersection for each section.

3. Clean up any missing or incorrect near points

Figure 6 shows the resulting PLSS point grid used as the

base for geocoding or mapping the UPCs from the PLSS

data for Luna County.

The process for geocoding the UPCs was as follows:

1. Convert the UPC, for example, 3051135428286 is

recoded as NM230230S0090W0SN150.

2. Identify the section and its reference point.

3. Create a new point based on the number of feet east-

west (4,280 ft) and north-south (2,860 ft) within the

section. This is the UPC-coded parcel centroid.

Catron County Results

Catron County provided a unique challenge because it

covers two PLSS quadrants. The first time the UPC map-

ping routines were run on this data set, the points were

“mirrored and flipped.” After the mapping routines had

been corrected, there were still problems because many

points fell outside the county boundaries. Further inves-

tigation revealed that within the county assessment data

Figure 5. UPC format in New Mexico

Figure 4. Digital mapping environment in New Mexico

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

7

non-PLSS “dummy” codes were used to identify personal

property and mobile homes. The routine was further

modified to identify valid ranges of UPC numbers that

would be expected to map real property and land parcels.

There also were many duplicate UPC values that had to

be combined to successfully join the mapped points to

the assessor attributes.

Figure 7 shows a portion of the county mapped points

and a portion of the attribute table that was built from

the joined features.

Luna County Results

Luna County had very good parcel data in CAD maps drawn

and maintained in AutoDesk. The processing of UPC codes

was done to support migrating the data from CAD to GIS.

Again, as in Catron County, the valid range of UPC values for

the county was developed, and dummy codes for personal

property and mobile homes were eliminated. Luna County

had 87 separate CAD maps (.dwg files) covering the county.

For Luna County the UPC annotation on the CAD maps

produced the most accurate result. Because of the many

irregularities in the PLSS in Luna County, the annotation

data more accurately placed a point for each parcel re-

cord. Once Triadic (assessment software) attributes were

joined to UPC points, a spatial join could be used to join

the points/attributes to parcel polygons built from the

CAD maps, yielding parcel polygons with CAMA attributes.

Figure 8 illustrates the resulting map with the attributes

from the joined assessor tables shown in the list of attributes.

Mora County Results

In Mora County roughly half of the county area is covered

by a land grant. In April 2012 the state completed a project

to extend the PLSS line work across the land grants, cre-

ating a virtual index for the PLSS that could be used for

the UPC coding. This index was extended from the New

Mexico CadNSDI and is now a feature data set integrated

into the CadNSDI geodatabase. This extended PLSS is

not surveyed on the ground and is not an official legally

binding land description system. It is only a computer-

generated extension of the PLSS used for indexing and

defining the UPC for parcels in the land grant.

The Mora County pilot test identified some coordi-

nate rounding errors in exporting data. The rounding

was inherent in the data export routines in the ArcMap

software. This problem was fixed by changing the export

Figure 6. Sample PLSS point grid for mapping UPCs for Luna

County

Figure 7. Quemado UPC results for Catron County

Figure 8. Mapping results for Luna County

8

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

procedures, so the UPCs could be mapped in their correct

location. Figure 9 shows the resulting map.

Benefits and Challenges

There is significant value in building and maintaining a

seamless, statewide GIS parcel layer. Comprehensive digital

parcel maps, in addition to being critical components of the

property valuation and assessment processes in a county,

serve as an important reference source for city, county, re-

gional, state, federal, and nongovernmental entities that

depend upon accurate property maps to meet the needs of

their constituents. Decision support and business processes

at all levels of government that contribute to operations,

public health and safety, asset management, transportation,

economic development, and resource allocation, conserva-

tion, and management rely on current property maps to be

effective. When integrated with data representing themes

such as topography, satellite and aerial imagery, hydrogra-

phy, natural resources, transportation and utility networks,

administrative boundaries, structures, and cultural features,

property ownership maps are considered a critical compo-

nent of a state’s spatial data inventory and base map.

New Mexico completed a Parcel Data Business Plan in

2009. Some of the benefits and challenges of building an

aggregated statewide standardized parcel data set from

the locally developed data were documented in that plan.

The benefits of standardized parcel data for the state

were identified as follows:

• The data can be placed in context with other state data

sets, providing solutions for many cross-jurisdictional

data needs.

• The data provide an opportunity to establish partner-

ships and communication with local parcel producers.

• The data provide communication and connection

with intergovernmental applications.

• The data provide an essential data set for state opera-

tions to build other statewide parcel-based data sets.

• The data increase the essential role of state coordination:

– Property data (assessed value, market value, im-

provements, net taxable value, and so on) can be

viewed, symbolized, and analyzed in a map.

– Sales transactions can be viewed, symbolized, and

analyzed in a map.

– Inconsistency in assessed value versus sale prices

can be discovered.

Figure 10 shows the taxable values in Catron County sym-

bolized by the size of the circle; larger values have a larger

circle. Thus, it is possible to observe the value patterns at a

glance and identify any possible outliers. With statewide data

like this, values can be compared across county boundaries

and statewide values can be seen at a glance.

For emergency responders and other essential govern-

ment users, the standardized parcel data set

Feature Article

Figure 9. PLSS extended into the John Scolly Land Grant in Mora County

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

9

• Reduces the time and level of effort required to obtain

parcel data

• Reduces redundant efforts in collecting, assembling,

and analyzing locally produced parcel data

• Increases the credibility of the products from emer-

gency response agencies because they know the cur-

rency and quality of their parcel information

• Saves the time and expense of compiling locally pro-

duced parcel data sets each year

• Allows for applications to be built around a consistent

data source.

For citizens affected by emergencies, the standardized

parcel data set

• Ensures that important information to service the

needs of the citizens can be accessed in times of

emergency

• Increases the value of the local taxpayer investment

by reducing duplicative collection

• Allows local government staff to provide essential sup-

port other than data distribution during emergencies

• Increases the likelihood that responding agencies will

coordinate their efforts, reducing response times to

citizens’ needs.

Moving Forward

One goal over the next few years is to mentor assessors and

their staff to modernize and improve their workflows and

Figure 10. Parcel points symbolized by total value for Catron County

10

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

Larry Brotman is the GIS Coordi-

nator for the New Mexico Taxation

and Revenue Department (TRD),

Information Technology Division. In

this capacity he serves as the primary

liaison for GIS (geographic informa-

tion systems) services and support to

TRD’s eight divisions including the

Property Tax Division (PTD). As a GIS

resource to PTD, Larry also provides

technical support and mapping guid-

ance to the state’s 33 county assessor

offices. Brotman has a master’s degree

in educational technology from the

University of New Mexico.

Nancy von Meyer, Ph.D., is vice

president of Fairview Industries in

Pendleton, South Carolina. She is

a nationally recognized leader in

land records and use of cadastral in-

formation for decision support. She

has been at Fairview Industries since

1983 and has more than 25 years of

GIS system design and implementa-

tion experience. Her efforts have

been applied in the areas of wildland

fire management, local land use

planning and management, energy,

and economic analysis.

Sharon Schiebold is a consultant with

Shared Vistas, LLC, in Grand Rapids,

Michigan. Sharon has 15 years of ex-

perience in county level parcel land

record administration and manage-

ment and 20 years of experience with

GIS. Sharon graduated from Michi-

gan State University with a combined

education in Natural Resource Man-

agement and Policy and Cartography.

Recently, Sharon has been active in

implementing the NSDI Cadastral

Standard for Wildland Fire in over

200 counties in 12 Western states.

business practices to create data (mapped and attributed)

that meet the state parcel data publishing standard. The

status of the parcel mapping and standardization efforts

as of December 2012 is as follows:

• As a result of a UPC geocoding project with EDAC

(funded with Broadband money), the PTD has a

blend of county parcel points and polygons (mostly

polygons) with varying degrees of data attribution.

• A near-term goal (a few months) is to build a standard-

ized statewide parcel point feature class converting

existing polygons to points and loading those along

with points from the UPC geocoding process in the

pilot counties; a long-term goal is to mentor the few

remaining counties without parcel polygons to mod-

ernize tools, skills, and workflows to develop data that

meet standards and allow for statewide standardized

parcel polygons.

• Current efforts in parcel data aggregation are limited

by the availability of staff time for loading the parcel

polygons into the NSDI Core Parcel feature class within

the New Mexico CadNSDI (standardized GIS represen-

tation of the PLSS). The PTD does not distribute any

assessor parcel data, aggregated or not, to any entity

without the express permission of respective assessors.

A second important foundation theme for New Mexico is

the address points. These are used in emergency response,

broadband services mapping, and wildland fire manage-

ment. Assessors distinguish between “mailing address”

(where the treasurer’s property tax bill must go for pay-

ment) and “site address” or “situs” (the physical location

of a property if it has been assigned an address). There

are still a number of counties that do not record situs in

their assessor databases, but several do and this trend is

growing. The state maintains a site address point location

for other applications but is planning on merging the site

address efforts so the information is kept current and cor-

rect in all the databases that need the information.

Feature Article

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

11

Table. New Mexico Parcel Data Standard

Standard Field

Names

Field Type and

Length Description of Data Element

STNAME String (2) The state name

STFIPS String (2) The state FIPS code, two-digit code

CNTYNAME String (50) The county name

CNTYFIPS String (3) The county FIPS code, three-digit code

STCNTYFIPS String (5) The state and county FIPS codes combined as a single field. Used to relate and link the parcel information to other records. It creates a

unique national parcel identifier when used as a prefix to the local parcel number.

GNISID Integer (Long) The geographic names information system identifier for the local place for the parcel. The default value is the county GNIS number, but

as this data set develops, individual parcels may have a GNIS identifier, such as local parks or attractions.

SOURCEAGENT String (100) The originating agency or source of the information for the feature or the data steward for data set

PARNO String (25) The local parcel number for the parcel record

NPARNO String (25) The local parcel number with the state and county FIPS added to the beginning of the local parcel number

CAMAPROPID String (10) Unique property number assigned by the valuation/assessment system and associated with a specific parcel

CAMAID String (10) Unique account/owner number assigned by the valuation/assessment system and associated with a specific taxpayer

LOCID String (18) Unique parcel identifier generated by calculating X and Y coordinate values for a point located within a parcel polygon

PARUSECODE String (50) The local assessment parcel use code

PARUSEDESC String (100) The local assessment parcel use description

STRUCT String (1) Is there a structure or improvement on the parcel (Y = yes, N = no)?

MULTISTRUCT String (1) Does this parcel have multiple structures (Y = yes, N = no)? If the total number of structures is not known but it is known that there are

multiple structures, this is populated. It is also populated when the exact number of multiple structures is known and the STRUCTNO is

greater than 1.

STRUCTNO Integer (Long) The number of structures on the parcel. This is populated when the source data indicate how many structures. This is used primarily to

support emergency planning and response.

BLDGCLASS String (50) Building classification, that is, residential, commercial, and so on

BLDGTOTSQFT String (25) Total building square feet

BLDGTOTVAL Double Total value for all structures

IMPROVVAL Double Improved value

IMPRVLALMISC Double Total miscellaneous value

LANDVAL Double The value of the land on the parcel

PARVAL Double The total value of the parcel (IMPROVVAL + LANDVAL)

PARVALTYPE String (50) The type of value reported in the parcel value fields such as assessed or market value

ASSESSVAL Double Assessed value

ASSESSDATE Date Most recent assessment date (00/00/0000 format)

ASSESSDTTX String (15) Assessment date as a text

VETEXEM String (50) Veterans exemption number 1

VETEXEMAMT Double Veterans exemption number 1 amount applied

VETEXEMB String (50) Veterans exemption number 2

VETEXEMBAMT Double Veterans exemption number 2 amount applied

HEDHOUSEXEM Double Head of household exemption amount applied

DISABEXEM String (1) Disability exemption (Y= yes, N = no)

NETTAXVALUE Double Full taxable value less all exemptions

SDNDFA String (1) Property tax rate district (sometimes referred to as school district); DFA Certificate of Property Tax Rates “category” identification

ZONING String (255) Legal zoning

OWNTYPE String (50) The owner type (e.g., federal, state, private). The domain of values for this attribute is international, tribal, federal, state, county, local,

private, nonprofit, other, unknown.

OWNNAME String (200) The primary surface owner name. The full name may be populated or the components of the name (first and last).

OWNFRST String (100) The primary surface owner first name

OWNLAST String (100) The primary surface owner last name

12

Fair & Equitable • June 2013

Feature Article

Table. New Mexico Parcel Data Standard

Standard Field

Names

Field Type and

Length Description of Data Element

SUBSURFOWN String (200) The name of the subsurface rights landowner

SUBOWNTYPE String (50) The subsurface owner type (see surface owner type domain list)

MAILADD String (200) The full mailing address as a single field. The mailing address may also be broken into its components.

MADDRNO String (10) The mailing address number

MADDSTNAME String (100) The mailing street name, the name without the type and directions

MADDPREF String (5) The mailing street prefix

MADDSTR String (50) The mailing street name, the name without the type and directions

MADDSTTYP String (10) The mailing street type, such as ST, AVE, BLVD

MADDSTSUF String (10) The mailing street suffix, typically a direction

MUNIT String (10) The mailing address unit, suite, or apartment number; may also be the half number

MCITY String (100) The mailing city name

MSTATE String (2) The mailing state name, two-letter abbreviation

MZIP String (15) The mailing ZIP code

SITEADD String (200) The full mailing address as a single field. The mailing address may also be broken into its component parts.

SADDNO String (10) The mailing address number

SADDSTNAME String (100) The mailing street name, the name without the type and directions

SADDPREF String (5) The mailing street prefix

SADDSTR String (50) The mailing street name, the name without the type and directions

SADDSTTYP String (10) The mailing street type, such as ST, AVE, BLVD

SADDSTSUF String (10) The mailing street suffix, typically a direction

SUNIT String (10) The mailing address unit, suite, or apartment number; may also be the half number

SCITY String (100) The mailing city name

LEGDECFULL String (255) The full tax legal description. This is generally needed when the parcel data do not include a map of the parcel.

LEGDECONE String (255) The full tax legal description

LEGDECTWO String (255) Legal description continued if one field is not enough

SUBDIVISION String (200) The name of the subdivision or condo that the parcel is in

TOWNSHIP Integer Township of parcel location

TOWNDIR String (1) Township direction (N = north, S = south)

RANGE Integer Range of parcel location

RANGEDIR String (1) Range direction (W = west, E = east)

SECTION Integer Section of parcel location

SALPRICE Double Sale price

SALDATE Date Sale date (00/00/0000 format)

SALDATETX String (15) Sale date as a text field

SALVALID String (1) Indicates “arm’s-length” transaction or other (Y = yes, N = no)

SALINVALID String (1) If the sale is invalid, explain.

SALASSESVAL Double Assessed value at time of most recent sale

SALVALAFTSL Double Assessed value following most recent sale

RECRDAREATX String (20) The record or recorded area as a text field. This may include the units of area as well.

RECRDAREANO Double The record or recorded area as a numeric field.

GISACRE Double The area of the feature in acres, computed from the GIS. This is not the record area.

SOURCEREF String (255) The reference to the source document. This could be a reference to a map or plat or a deed as well as including the document type.

SOURCEDATE Date The date of the source document (listed in the source reference) that was used to generate the parcel information

REVISEDDATE Date The date of the last revision of the parcel record. This may be the initial create date if that is the last revision.

REVDATETX String (15) The date (as text) of the last revision of the parcel record. This may be the initial create date if that is the last revision. Date as a text

field is useful to accommodate varying date formats from various databases.

(continued)