Ko tō tātou kāinga tēnei

Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry

into the terrorist attack on Christchurch

masjidain on 15 March 2019

ROYAL COMMISSION OF INQUIRY

INTO THE TERRORIST ATTACK

ON CHRISTCHURCH MOSQUES

ON 15 MARCH 2019

TE KŌ

MIHANA UIUI A TE WHAKAEKE

KAIWHAKATUMA I NGĀ WHARE

KŌRANA O ŌTAUTAHI I TE

15 O POUTŪ-TE-RANGI 2019

Volume 2:

Parts 4–7

26 November 2020

Ko tō tātou kāinga tēnei

Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry

into the terrorist attack on Christchurch

masjidain on 15 March 2019

Published 26 November 2020

978-0-473-55326-5 (PDF)

978-0-473-55325-8 (Soft cover)

(C) Copyright 2020

This document is available online at:

www.christchurchattack.royalcommission.nz

Printed using ECF and FSC certified paper

that is also Acid free and biodegradable.

163

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Part 4

The terrorist

Chapter 1 – Introduction 165

Chapter 2 – The individual’s upbringing in Australia 168

Chapter 3 – World travel – 15 April 2014 to 17 August 2017 172

Chapter 4 – General life in New Zealand 184

Chapter 5 – Preparation for the terrorist attack 197

Chapter 6 – Planning the terrorist attack 214

Chapter 7 – Assessment of the individual and the terrorist attack 231

Chapter 8 – Questions asked by the community 235

Glossary – Terms commonly used in Part 4 243

164

Distressing

Content

165

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Chapter 1: Introduction

1 Our Terms of Reference directed us to inquire into:

3(a) the individual’s activities before the terrorist attack, including—

(i) relevant information from his time in Australia; and

(ii) his arrival and residence in New Zealand; and

(iii) his travel within New Zealand, and internationally; and

(iv) how he obtained a gun licence, weapons, and ammunition; and

(v) his use of social media and other online media; and

(vi) his connections with others, whether in New Zealand or internationally.

We address each of these issues in this Part, although we go into how the individual obtained

a firearms licence in much greater detail in Part 5: The firearms licence.

2 We interviewed family and associates of the individual, members of New Zealand Police and

other officials. We examined, tested and analysed thousands of pages of evidence. Also,

after the individual pleaded guilty to the charges against him and it was clear that there

would be no trial, we interviewed him.

3 When we interviewed the individual, his responses to some questions were limited and,

on occasion, non-existent. We have distinct reservations about, and in some instances do

not believe, aspects of what he told us. That said, much of what he said was credible, for

instance his explanations of certain documents he created. More generally the interview

provided insights into his activities and thinking, sometimes in ways he did not intend.

4 It may be helpful at this stage to outline some points that provide a little context ahead of the

detailed discussion about the individual that follows.

5 The individual was born in October 1990 in Grafton, New South Wales in Australia, which is

where he went to primary and secondary school. His mother is Sharon Tarrant and he has

one older sister, Lauren Tarrant. His father, Rodney Tarrant, is deceased.

6 His upbringing in Australia was marked by a number of stressors, including his parents’

separation and his mother’s subsequent relationship with an abusive partner. His father

developed a form of cancer (mesothelioma) caused by exposure to asbestos and later

died by suicide in April 2010.

7 Before he died, Rodney Tarrant settled a claim for damages relating to his exposure to

asbestos. With money that largely came from this settlement, he gave AU$457,000 to each

of his two children.

166

Distressing

Content

8 The individual expressed racist ideas from an early age. He was also an avid internet user

and online gamer. He had few childhood friends.

9 After leaving school, the individual worked as a personal trainer at a local gym until 2012

when he suffered an injury. He never again worked in paid employment. Instead, he lived

off the money that he had received from his father and income from investments made

with it. Although in his manifesto the individual claimed to have made money dealing in

cryptocurrency, he told us that he generally used cryptocurrency only for transactions (that

is, as currency). His banking records indicate only limited relevant transactions that total

less than AU$6,000. We have seen no evidence that he made any significant profits through

cryptocurrency.

10 With the money from his father, the individual travelled extensively. First in 2013, he explored

New Zealand and Australia and then between 2014 and 2017 he travelled extensively around

the world.

11 The individual has a close relationship with his sister Lauren Tarrant, and to a lesser extent

with his mother Sharon Tarrant, but his relationships with others have been limited and

superficial. He describes himself as an introvert. He told us that he had suffered from social

anxiety since childhood and found socialising with others stressful. Without a job, he had

no need to associate with people in workplaces and his frequent and usually solitary travel

meant he did not form enduring relationships with others. This meant that his self-described

introversion was not mitigated by the usual daily interactions that most people experience

in their regular lives. Accordingly, there was limited opportunity for the hard edges of his

political thinking to be softened by regular and lasting connections with people with different

views. In fact, his limited personal engagement with others left considerable scope for

influence from extreme right-wing material, which he found on the internet and in books.

12 By January 2017, he was planning to move to New Zealand later that year and to take up

shooting. We know this because in January that year he emailed the Bruce Rifle Club

(which is near Dunedin) inquiring whether it was still operating. He indicated an intention

to move to Dunedin in August that year. In February 2017 he booked flights to New Zealand

to arrive in Auckland on 17 August 2017 and then on to Dunedin on 20 August 2017. We see

these activities as the first manifestations of his terrorist intent.

167

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

13 We are satisfied that by January 2017 the individual had a terrorist attack in mind. We are

also satisfied that when the individual came to live in New Zealand on 17 August 2017, it was

with a fully-developed terrorist ideology based on his adoption of the Great Replacement

theory and his associated beliefs that immigration, particularly by Muslim migrants, into

Western countries is an existential threat to Western society and that the appropriate

response (at least for him) was violence.

14 As foreshadowed in his January 2017 emails to the Bruce Rifle Club, the individual moved to

Dunedin, and on 1 September 2017 – just 15 days after arriving in New Zealand – he took the

first step towards obtaining a firearms licence. From that time on, his primary focus in life

was planning and preparing for his terrorist attack.

15 The individual is capable of pursuing an idea or plan of action with considerable

determination and with no assistance from others. Indeed, he can be single-minded to the

point of obsession. This is evidenced by his ability to pursue fitness aims, the development

and persistence of his racist and extreme right-wing patterns of thinking, his extensive travel

and, most particularly, the preparation and planning for the terrorist attack he carried out

on 15 March 2019. For the more than 18 months he lived in New Zealand preparing for the

terrorist attack, he remained resolutely focused, attempting to maintain operational security

from which there were only limited lapses.

16 In this Part we explain the individual’s trajectory from childhood in Australia through to the

terrorist attack in New Zealand. In doing so, we draw on some of the concepts and ideas

outlined in Part 2, chapter 5, on right-wing extremism. We have also tried to identify aspects

of his behaviour, particularly those relevant to his terrorist ideology and preparation for the

terrorist attack, which might have brought him to the attention of Public sector agencies, and

specifically counter-terrorism agencies. This is something we deal with in various other Parts

of this report but in this Part we discuss all the aspects of his conduct that are relevant to

this phase of our inquiry.

168

Distressing

Content

Chapter 2: The individual’s upbringing

in Australia

1 Grafton, where the individual was born and brought up, is about 600 kilometres north

of Sydney. Approximately 19,000 people live there, just under 10 percent of whom are

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Australians.

2 The individual’s parents, Rodney and Sharon Tarrant, separated when he was young.

1

After the terrorist attack, Sharon Tarrant told Australian Federal Police that her children

were traumatised by the separation and other events, including the loss of their family home

in a fire and the death of their grandfather. She also said that the individual’s personality

changed after the separation, with him becoming clingy, anxious and not socialising well

with others. The individual told us he suffered from social anxiety from childhood.

3 Following their parents’ separation, the individual and Lauren Tarrant initially lived with their

mother and later with their mother and her new partner. That relationship was violent, with

the new partner assaulting Sharon Tarrant and the children. An apprehended violence order

was taken out against his mother's partner to protect the individual. Lauren Tarrant, and

later the individual, went to live with their father.

4 Sharon Tarrant told the Australian Federal Police that the individual put on weight between

the ages of 12 to 15. This led to bullying by other students at school. The individual had

very few friends at school and, after he left school, he seems to have stayed in touch with

only two of them, to whom we will refer as “school friend one” and “school friend two”.

His contact with them was episodic.

5 From the age of six or seven, the individual was interested in video games. He became

particularly interested in massively multiplayer online role-playing games, other online

role-playing games and first-person shooter games. As a child he had unsupervised access

to the internet from a computer in his bedroom. He spent much of his free time at school

accessing the internet on school computers. In 2017, he told his mother that he had started

using the 4chan internet message board when he was 14 years old.

6 The individual began expressing racist ideas from a young age, including at school and when

referring to his mother’s then partner’s Aboriginal ancestry. He was twice dealt with by one

of his high school teachers, who was also the Anti-Racism Contact Officer,

2

in respect of

anti-Semitism. This teacher described the individual as disengaged in class to the point of

quiet arrogance, but also well-read and knowledgeable, particularly on certain topics such

as the Second World War.

1

The year the parents separated, as provided by Sharon and Lauren Tarrant to Australian Federal Police, are not the same.

Sharon Tarrant said she separated from Rodney Tarrant in 2000 (when the individual was aged nine or ten) and Lauren Tarrant

said they separated when the individual was aged seven.

2

Under the New South Wales Department of Education Anti-Racism Policy, all schools are required to have a trained Anti-Racism

Contact Officer and to implement strategies that lead to timely responses to both direct and indirect racism. The Anti-Racism

Contact Officer assists parents, staff and students who have complaints regarding racism and facilitates the complaints handling

process.

169

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

7 In 2006 or 2007, when the individual was 16 or 17, his father was diagnosed with pleural

mesothelioma, a form of lung cancer caused by exposure to asbestos. After the diagnosis

Rodney Tarrant became increasingly depressed and his children did not cope well. The

individual began exercising compulsively at gyms and following a strict diet. He lost around

52 kilograms in weight.

8 As Rodney Tarrant’s health deteriorated he needed palliative care and in April 2010 he died

by suicide at home. Information provided to Australian Federal Police after the terrorist

attack indicated that the individual “discovered” his father’s body, having previously agreed

with his father that he would do so. The individual was reluctant to engage with us on this

issue. Given it was not particularly relevant to our inquiry, we did not push him once he gave

an undetailed and not particularly convincing denial of involvement in his father’s suicide.

What is relevant for our purposes is that the illness and death of his father caused the

individual much stress.

9 Lauren Tarrant received counselling about her family situation, particularly the anger and

abuse from Sharon Tarrant’s partner. As far as we know, the individual received limited

counselling. This was through the palliative care system when his father was ill and shortly

after he died. The individual told us that he had not sought treatment for his social anxiety.

10 Prior to his death, Rodney Tarrant gave the individual and his sister around AU$80,000 each.

Following his death, both children received more money from his estate, bringing the total

to around AU$457,000 each. This was largely from the settlement of a claim for damages

arising out of the exposure to asbestos, which had caused his mesothelioma.

11 The individual continued to play video games regularly after his father’s death. He often

played online with a group of people including school friend one and a New Zealander,

whom he had met on the internet and to whom we refer as the individual’s “gaming friend”.

During these games, the group would often chat online and the individual would openly

express racist and far right views.

12 Apart from gaming and spending time on the internet, the individual also maintained his

interest in keeping fit. He joined the Big River Gym in Grafton at the end of his final high

school year. Around mid-2009, he qualified as a personal trainer and worked at the gym,

taking group classes and one-on-one personal training sessions. The owner and operator

of the Big River Gym described the individual as a good personal trainer. During this time

the individual trained by himself for two to three hours every day.

Section 15

orders

170

Distressing

Content

13 The individual told us that he began to think politically when he was about 12 and that

his primary concerns have been about immigration, particularly by Muslim migrants into

Western countries. In his manifesto he said that he had no complaints with ethnic

people, if they remained in their places of birth. Those on the far right, particularly

ethno-nationalists (as described in Part 2, chapter 5), sometimes assert similar views

while disingenuously denying being racist. Aspects of the individual’s life are consistent

with his description of his views. When he was still working as a personal trainer in Grafton,

he carried out community work in an Australian Aboriginal community. He told us that

his relationships with members of this community were generally good and that he had

admiration for some of its leaders. When travelling he engaged with people from many

different ethnicities. When we interviewed him, he denied being racist. On the other hand

he accepted in his manifesto that he was racist, a self-assessment that we accept.

14 As the individual grew older, he told his sister that he thought he was autistic and possibly

sociopathic. He also said that he did not care for people, including his own family, but knew

that he should. His friendships with those outside his family were limited and we have seen

no evidence that the individual was involved in sustained romantic or sexual relationships.

15 The individual stopped working at the Big River Gym in 2012 after suffering an injury.

It was at this point he decided to use the money he had inherited from his father to travel.

He did not have any ties, connections or purpose in life that prevented him from travelling.

16 The individual travelled to New Zealand for a holiday from 28 March 2013 to 29 May 2013.

3

School friend one accompanied him for the first part of the trip. When they arrived,

they both stayed for around three days in Waikato with gaming friend and their parents.

As mentioned above, the individual had come to know gaming friend online, but this was

the first time gaming friend and the individual met each other in person.

17 This was also the first time that gaming friend’s parent met the individual. Gaming friend’s

parent said the individual did not talk in a way that was of concern and described him as

“polite” and “nice”. Gaming friend and their parent are keen shooters and took the individual

and school friend one to a shooting club twice and possum hunting. These were the

individual’s first experiences using firearms. The visits of the individual, gaming friend and

school friend one were recorded in the register of the shooting club.

18 The individual spent approximately two weeks travelling around New Zealand in a campervan

with school friend one and gaming friend. Gaming friend had not originally intended to go

on the trip but decided to join them at the last minute to play peacemaker between the

individual and school friend one who had been arguing with each other.

3

This was the individual’s second time visiting New Zealand. The individual’s first visit to New Zealand was as a child with his

father and sister, arriving on 12 July 1999 and departing on 22 July 1999.

Section 15

orders

171

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

19 At the end of the two weeks, they spent one more night at gaming friend’s family home before

school friend one returned to Australia and the individual visited other parts of New Zealand

on his own.

20 While travelling on his own, the individual visited Dunedin. We also know that he travelled

through Whanganui, because he had a minor car accident there on 6 May 2013 when he

pulled off the road onto the verge and his vehicle rolled forward down a bank. The individual

was the only person in the car when he had the accident and there were no other vehicles

involved. New Zealand Police attended the accident, but no enforcement action was taken.

At the end of this trip he spent a few more nights with gaming friend and their family before

returning to Australia.

21 On the individual’s return from New Zealand he drove a van around Australia for about nine

months between May 2013 and February 2014. During his travels, he visited Port Arthur in

Tasmania. We discuss the possible relevance of this in Part 6: What Public sector agencies

knew about the terrorist.

Section 15

orders

172

Distressing

Content

Chapter 3: World travel – 15 April 2014 to

17 August 2017

3.1 Where he travelled and what he did

1 Between 15 April 2014 and 17 August 2017, the individual travelled extensively and always

alone, except for his travel to North Korea as part of a tour group. The countries that we

know the individual visited, or transited through, are set out in the table and world map

below. This has been pieced together from a range of sources as part of our inquiry.

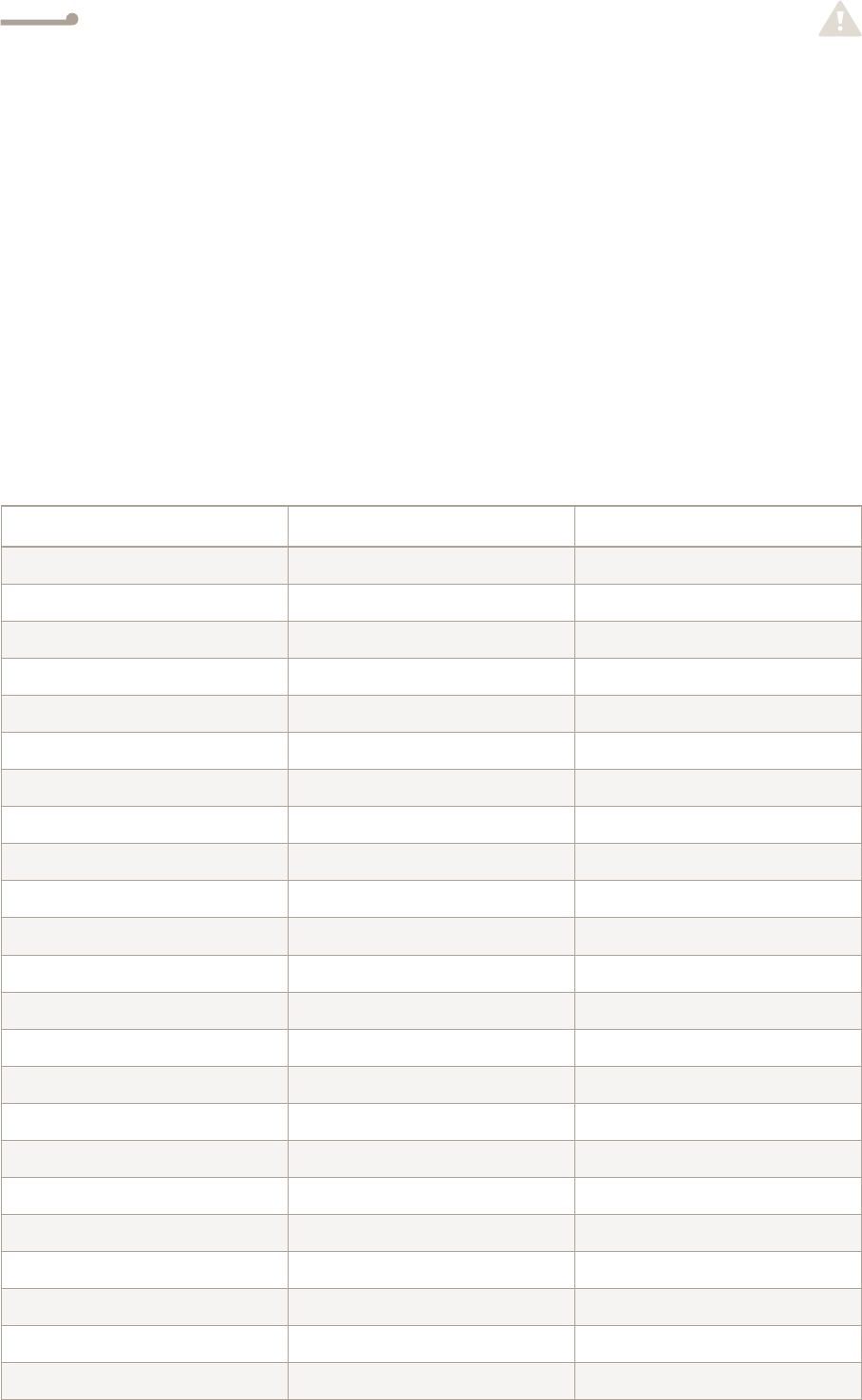

Table 1: The individual’s international travel between 2014–2017

Country visited Arrived Departed

Indonesia 15 April 2014 2 May 2014

Singapore 2 May 2014 6 May 2014

Malaysia 6 May 2014 22 May 2014

Thailand 22 May 2014 28 June 2014

Laos 28 June 2014 10 July 2014

Cambodia 10 July 2014 22 July 2014

Vietnam 22 July 2014 22 August 2014

Hong Kong 22 August 2014 29 August 2014

Macau 29 August 2014 30 August 2014

Hong Kong 30 August 2014 3 September 2014

China 3 September 2014 8 September 2014

North Korea 8 September 2014 18 September 2014

China 18 September 2014 17 October 2014

South Korea 17 October 2014 13 November 2014

Taiwan 13 November 2014 1 December 2014

Malaysia (transit) 1 December 2014 1 December 2014

Myanmar 1 December 2014 29 December 2014

China 29 December 2014 28 January 2015

Philippines 28 January 2015 2 March 2015

China 2 March 2015 31 March 2015

Japan 31 March 2015 20 May 2015

China 20 May 2015 18 June 2015

Kyrgyzstan 18 June 2015 30 June 2015

173

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Country visited Arrived Departed

Armenia 30 June 2015 12 July 2015

Georgia 12 July 2015 19 August 2015

Ukraine 19 August 2015 8 September 2015

Russia 8 September 2015 8 October 2015

Singapore (transit) 8 October 2015 8 October 2015

China 8 October 2015 29 October 2015

Nepal 29 October 2015 21 November 2015

India 21 November 2015 18 February 2016

Iran Unknown 17 March 2016

Turkey 17 March 2016 20 March 2016

Greece 20 March 2016 18 April 2016

Turkey (transit) 18 April 2016 18 April 2016

Slovenia 18 April 2016 4 May 2016

Hungary 4 May 2016 24 May 2016

Slovakia 25 May 2016 6 June 2016

Czech Republic 9 June 2016 17 June 2016

United Arab Emirates

(transit)

18 June 2016 18 June 2016

Australia 19 June 2016 16 July 2016

Indonesia 16 July 2016 12 September 2016

Malaysia (transit) 12 September 2016 12 September 2016

Turkey 13 September 2016 25 October 2016

Israel 25 October 2016 4 November 2016

Jordan 4 November 2016 10 November 2016

United Arab Emirates 10 November 2016 15 November 2016

Oman 15 November 2016 24 November 2016

United Arab Emirates

(transit)

24 November 2016 24 November 2016

Ethiopia 24 November 2016 28 November 2016

Egypt (transit) 29 November 2016 29 November 2016

174

Distressing

Content

Country visited Arrived Departed

Greece (transit) 29 November 2016 29 November 2016

Romania 29 November 2016 10 December 2016

Greece (transit) 10 December 2016 10 December 2016

Egypt 10 December 2016 21 December 2016

Morocco 21 December 2016 24 December 2016

Turkey (transit) 24 December 2016 24 December 2016

Croatia 25 December 2016 28 December 2016

Serbia 28 December 2016 30 December 2016

Montenegro 30 December 2016 2 January 2017

Bosnia and Herzegovina 2 January 2017 3 January 2017

Croatia 3 January 2017 31 January 2017

Spain 31 January 2017 24 February 2017

Portugal 24 February 2017 14 March 2017

Spain 14 March 2017 30 March 2017

France 1 April 2017 1 May 2017

Ireland 1 May 2017 8 May 2017

Scotland 8 May 2017 10 May 2017

Iceland 10 May 2017 20 May 2017

Scotland (transit) 20 May 2017 20 May 2017

England (transit) 20 May 2017 20 May 2017

Canada (transit) 20 May 2017 21 May 2017

Peru (transit) 22 May 2017 22 May 2017

Bolivia 22 May 2017 2 June 2017

Peru 2 June 2017 17 June 2017

Canada (transit) 17 June 2017 17 June 2017

England (transit) 18 June 2017 18 June 2017

Scotland (transit) 18 June 2017 18 June 2017

Kenya 19 June 2017 24 June 2017

Tanzania 25 June 2017 3 July 2017

175

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Country visited Arrived Departed

Malawi (transit) 6 July 2017 6 July 2017

Zambia 9 July 2017 11 July 2017

Botswana 13 July 2017 14 July 2017

Zimbabwe 14 July 2017 17 July 2017

Botswana 17 July 2017 22 July 2017

Namibia 23 July 2017 2 August 2017

South Africa 2 August 2017 8 August 2017

United Arab Emirates

(transit)

9 August 2017 9 August 2017

Australia 10 August 2017 17 August 2017

2 The individual continued to use the internet during his travels. He communicated with

Sharon and Lauren Tarrant on Skype and Facebook Messenger and sporadically used

Facebook Messenger to contact online friends, including gaming friend. He also posted

photos of his travels on Facebook. We have no doubt that he visited right-wing internet

forums, subscribed to right-wing channels on YouTube and read a great deal about

immigration, far right political theories and historical struggles between Christianity and

Islam. And, as we will explain, he also posted some right-wing and threatening comments.

3 While extremist groups (including violent extremists) can be found in some of the countries

the individual visited, there is no evidence that he met with them. Likewise, there is no

evidence that he engaged in training or investigated potential targets. And although some

of the sites he visited may have had resonance for him because of associations with past

military action between Christianity and Islam, this is not the case with the vast majority

of the destinations to which he travelled.

4 The individual told his mother, sister, his sister’s partner and gaming friend that he had

been mugged while in Africa and all of them saw this as having increased the intensity of his

racism. The individual told us that this incident had happened in Ethiopia and that it had not

significantly affected his thinking. Despite his denial to us, it is possible that this incident

was of some moment in the development of his thinking. As will become apparent, however,

we see other influences as far more significant.

Section 15

orders

176

Distressing

Content

Pakistan

Bulgaria

Austria

Poland

Estonia

Latvia

Lithuania

New Zealand

Bolivia

South Africa

Namibia

Botswana

Zimbabwe

Zambia

Tanzania

Kenya

Portugal

Spain

France

Morocco

Ireland

Iceland

Scotland

Iran

Armenia

Georgia

Romania

Czech Rep.

Slovakia

Hungary

Serbia

Croatia

Slovenia

Mont.

Greece

Bos.

& Her.

Ukraine

India

Indonesia

Singapore

Philippines

Malaysia

Laos

Myanmar

Thailand

Macau

South Korea

Taiwan

North Korea

China

Australia

Russia

Japan

Nepal

Kyrgyztan

United Arab

Emirates

Jordan

Egypt

Ethiopia

Oman

Israel

Turkey

Peru

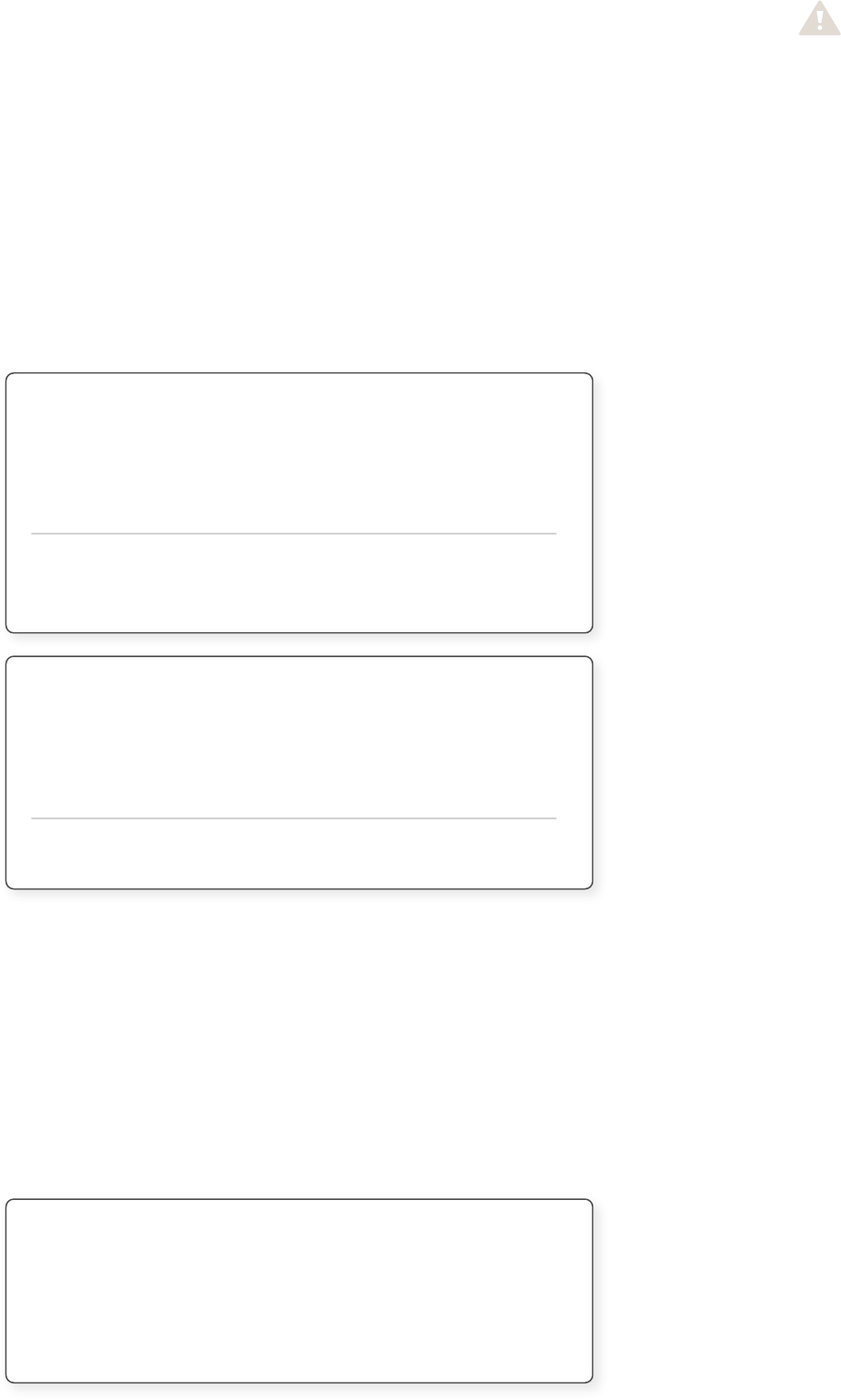

Figure 7: The individual’s international travel

Trip 1 – 15 April 2014 to 17 August 2017 (see chapter 3 of this Part)

Trip 2 – 16 January 2018 to 31 January 2018 (see chapter 4 of this Part)

Trip 3 – 30 May 2018 to 5 June 2018 (see chapter 4 of this Part)

Trip 4 – 17 October 2018 to 28 December 2018 (see chapter 4 of this Part)

176

177

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Pakistan

Bulgaria

Austria

Poland

Estonia

Latvia

Lithuania

New Zealand

Bolivia

South Africa

Namibia

Botswana

Zimbabwe

Zambia

Tanzania

Kenya

Portugal

Spain

France

Morocco

Ireland

Iceland

Scotland

Iran

Armenia

Georgia

Romania

Czech Rep.

Slovakia

Hungary

Serbia

Croatia

Slovenia

Mont.

Greece

Bos.

& Her.

Ukraine

India

Indonesia

Singapore

Philippines

Malaysia

Laos

Myanmar

Thailand

Macau

South Korea

Taiwan

North Korea

China

Australia

Russia

Japan

Nepal

Kyrgyztan

United Arab

Emirates

Jordan

Egypt

Ethiopia

Oman

Israel

Turkey

Peru

177

178

Distressing

Content

3.2 The individual’s account of his mobilisation to violence

5 According to his manifesto, the individual’s decision to engage in terrorism was largely a

response to events that occurred and his own experiences in 2017, in particular:

a) Dā’ish-inspired terrorist attacks in Europe, particularly the Stockholm attack on

7 April 2017 that killed five people, including eleven-year-old Ebba Åkerlund (whose

name the individual painted on one of the firearms used in the terrorist attack);

b) the outcome of the 2017 presidential election in France, particularly Marine Le Pen’s

loss on 7 May 2017;

4

and

c) the number of migrants he saw in French cities and towns during his visit between

1 April 2017 and 1 May 2017.

6 His account suggests that his terrorist attack:

a) was retaliation for Islamist extremist terrorist events in Europe;

b) followed his recognition of the inability of the far right to obtain a democratic mandate

for addressing immigration; and

c) was influenced by nostalgia for a pre-immigration past.

7 Ideas of this sort are commonplace on the far right. We see his language as calculated to

draw support, or at least sympathy, from those on the far right.

8 The events and experiences to which the individual referred may have been significant to

him. But as will become apparent we are satisfied that by the beginning of 2017 – that is

before these events and experiences discussed above – he had already formed the intention

of carrying out a terrorist attack. Indeed, we see this account of his mobilisation to violence

as an exercise in propaganda and there is more on this in chapter 4 of this Part.

5

3.3 Our assessment of the timing of his mobilisation to violence

9 We think the individual’s mobilisation to violence occurred earlier than the events to which

he referred in his manifesto. Sharon Tarrant considers that the more the individual travelled

the more racist he became. This sentiment was echoed by gaming friend. His sister recalls

that when he returned to Australia for a month in June 2016, he was a changed person – he

spoke regularly of politics, religion, culture, history and past wars, particularly those he had

learned about during his travels.

4

Marine Le Pen is the President of the National Rally political party (previously named the National Front).

5

See the “Boiling the Frog” comment in chapter 4 of this Part.

Section 15

orders

179

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

10 After the terrorist attack, Sharon Tarrant told the Australian Federal Police that in early 2017,

she felt the individual’s racism was becoming more extreme. She remembered him talking

about how the Western world was coming to an end because Muslim migrants were coming

back into Europe and would out-breed Europeans. She began to have concerns for his

mental health.

11 The narratives provided by the people we have just mentioned are supported by what we

know of the individual’s internet activity, donations to right-wing organisations, first contact

with the Bruce Rifle Club and the timing of his travel bookings to come to New Zealand.

12 The individual was one of more than 120,000 followers of the United Patriots Front Facebook

page. United Patriots Front was a far right group based in Australia. Between April 2016 and

early 2017, the individual made approximately 30 comments on their Facebook page. At that

time, the United Patriots Front was led by Blair Cottrell. Several of the posts made by the

individual expressed support for Blair Cottrell. For example, when Donald Trump was elected

President of the United States of America, the individual posted on Facebook “globalists and

Marxists on suicide watch, patriots and nationalists triumphant – looking forward to Emperor

Blair Cottrell coming soon”.

6

The individual also expressed support for Blair Cottrell on the

True Blue Crew Facebook page. The True Blue Crew is another far right Australian group.

13 In one post to the United Patriots Front Facebook page, the individual threatened critics

of Blair Cottrell by saying that “communists will get what communists get, I would love to

be there holding one end of the rope when you get yours traitor”.

7

In August 2016, he sent

comments via Facebook Messenger to an Australian critic of the United Patriots Front,

which included “I hope one day you meet the rope.”

8

This threat was allegedly reported to

Australian police but no action was taken. We see references to “the rope” as alluding to the

“Day of the Rope” which features in The Turner Diaries and, as explained in Part 2, chapter 5,

is sometimes used by those on the extreme right to refer to a race war.

14 Blair Cottrell told media he was aware of an AU$50 donation to the United Patriots Front

made by the individual.

9

We have been unable to verify this donation.

6

Alex Mann “Christchurch shooting accused Brenton Tarrant supports Australian far-right figure Blair Cottrell” ABC

(Australia, 23 March 2019) www.abc.net.au.

7

Alex Mann, footnote 6 above.

8

Graham Macklin “The Christchurch Attacks: Livestream Terror in the Viral Video Age” (2019) vol. 12 Combating Terrorism

Centre at page 24.

9

Alex Mann, footnote 6 above.

180

Distressing

Content

15 The last time the individual was active on the United Patriots Facebook page was in January

2017. Following Facebook’s removal of the United Patriots Front Facebook page in May 2017,

several former members of that group created a new far right group, called The Lads Society,

which had club houses in Sydney and Melbourne. Thomas Sewell (a New Zealander based

in Victoria, Australia and a founding member of The Lads Society) contacted the individual

online and invited him to join.

10

However, the individual declined this offer, citing his

upcoming move to New Zealand.

11

He did, however, join a Facebook page created by

The Lads Society and became an active member online. We will cover this in chapter 4

of this Part.

16 On 15 January 2017 and 17 January 2017, the individual made donations to right-wing

organisations, Freedomain Radio (a podcast and YouTube channel created by Canadian

Stefan Molyneux, who is prominent member of the far right) and the National Policy Institute

(a white supremacist think tank and lobby group based in the United States of America).

Table 2: The individual’s donations to right-wing organisations in early 2017

Transaction

date

Description as per bank

statement

Currency Amount

15 January 2017 PayPal: Freedomain Radio AUD $138.89

17 January 2017 PayPal: National Policy Institute AUD $138.06

17 On 21 January 2017, the individual emailed the Bruce Rifle Club enquiring whether the Club

was still open. During the communications that followed, he said that he was “not in the

area” but was looking to “move down that way sometime in August”.

10

Patrick Begley “Threats from white extremist group that ‘tried to recruit Tarrant’” The Sydney Morning Herald

(Australia, 2 May 2019) www.smh.com.au.

11

Patrick Begley, footnote 10 above.

181

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Date: 21 January 2017

From: [The individual]

To: Bruce Rifle Club

Hey there, just wondering if the Bruce Rifle Club is still

operating? And if so are they accepting new members?

Date: 21 January 2017

From: Bruce Rifle Club

To: [The individual]

Yep still going.

Date: 21 January 2017

From: [The individual]

To: Bruce Rifle Club

That’s great news. I’m actually not in the area, just looking

to move down that way sometime in August and was

hoping there was a Rifle club I could join, happy to see you

guys are still running. Hopefully will drop in sometime in

August …

18 When we asked the individual about this, he told us that he had developed an interest in

firearms, and it was this interest that had prompted him to make contact with the Bruce Rifle

Club. We do not accept his explanation. At this point, the individual’s only experiences with

firearms had been during his 2013 visit to New Zealand and, as he told us, at two overseas

tourist attractions while travelling. As his actions after he arrived in Dunedin show, his only

interest in firearms was to develop proficiency in their use to carry out a terrorist attack.

19 In February 2017, the individual booked flights to arrive in Auckland on 17 August 2017 and to

fly from Auckland to Dunedin on 20 August 2017.

182

Distressing

Content

3.4 Evaluation of the significance of the individual’s travel

20 The longest visit the individual made to any one country was to India where he stayed

between 21 November 2015 and 18 February 2016. The countries that he visited for periods

of about a month or more were:

a) Thailand (22 May 2014–28 June 2014);

b) Vietnam (22July 2014–22 August 2014);

c) China (3 September 2014–8 September 2014; 18September2014–17 October 2014;

29 December 2014–28 January 2015; 2 March 2015–31 March 2015; 20 May 2015–18 June

2015; and 8 October 2015–29 October 2015);

d) South Korea (17 October 2014–13 November 2014);

e) Myanmar (1 December 2014–29 December 2014);

f) the Philippines (28 January 2015–2 March 2015);

g) Japan (31 March 2015–2 May 2015);

h) Georgia (12 July 2015–19 August 2015); and

i) Russia (8 September 2015–8 October 2015).

21 Of the countries that made up the former Yugoslavia, he visited:

a) Slovenia (18 April 2016–4May 2016);

b) Croatia (25 December–28 December 2016 and 3–31 January 2017);

c) Serbia (28–30 December 2016);

d) Montenegro (30 December 2016–2 January 2017); and

e) Bosnia and Herzegovina (2 January–3 January 2017).

22 The individual was thus in Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina between

25December 2016 to 31 January 2017. It was during this time that he wrote to the

BruceRifle Club, which we see as the first tangible indications of his mobilisation to violence.

183

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

23 The individual’s presence from late December 2016 to late January 2017 in the areas in which

wars associated with the breakup of the former Yugoslavia had taken place may have been

related to his decision to write to the Bruce Rifle Club in January 2017. But, as we have

noted, there is no evidence of the individual engaging in training in his travels. Given the

limited periods of time he stayed in the countries he visited, there would not have been

much opportunity to do so. This is particularly so given the individual travelled between

cities and towns in each of the countries. Nor is there evidence of the individual meeting

up with right-wing extremists. As well, most of the countries in which the individual spent

substantial periods of time have no association with right-wing extremism.

24 In the aftermath of the terrorist attack of 15 March 2019, the New Zealand Security

Intelligence Service received a substantial number of reports from international partners

in relation to the individual, which we have reviewed. On the basis of the material that we

have seen, it is likely that the individual occasionally shared some of his political views and

interests with those he met during this travels. It is also at least possible that he visited

some places because of their association with historical events in which he was interested.

But more significantly, based on the information we have seen, there is no suggestion that the

individual received training or met with known right-wing extremists.

25 Against this background, we see the primary significance of the individual’s travel as being

that it provided the setting in which his mobilisation to violence occurred rather than its

cause. It may be that the individual’s experiences while travelling had some role to play in

his mobilisation to violence. But of far more materiality was his immersion during this period

in the literature, and probably the onlineforums, of the far right and the social isolation of his

solo travel. And, as will be apparent, we do not accept the individual’s account of when and

why he decided to engage in terrorism – an account that we see as propaganda.

26 We see the individual’s travel between 2014 and 2017 as largely a function of his

circumstances and personality. He had the money to travel and no employment, personal

relationships or other purpose in life that precluded it. The purpose of the travel was not

to meet up with extreme right-wing people or groups or engage in training activities or

reconnaissance of possible targets. Put simply, he travelled widely because he could and

had nothing better to do.

184

Distressing

Content

Chapter 4: General life in New Zealand

4.1 Overview

1 We are satisfied that by the time the individual arrived in New Zealand in August 2017 he

intended to commit a terrorist attack. This was the primary focus of his life in New Zealand.

It involved, amongst other things, equipping himself with weapons, developing firearms

expertise, bulking up at a gym, identifying targets and planning.

2 In the next chapter we discuss in detail his preparation and planning. In this chapter we

seek to provide context for what is to come, discussing those of his activities that were not

focused on preparations for a terrorist attack. We address his arrival in New Zealand and

taking up residence in Dunedin, his finances, associations with others, international travel

from New Zealand, internet activity and donations to overseas right-wing organisations and

individuals.

4.2 Arrival in New Zealand and taking up residence in Dunedin

3 The individual flew into New Zealand on 17 August 2017. As an Australian citizen, he was

eligible for, and was granted, a resident visa on arrival in New Zealand. This is discussed in

more detail in Part 8, chapter 8.

4 On arrival at Auckland International Airport, the individual was picked up by gaming friend

and their parent. They drove him to their home in Waikato where he stayed for three nights

before flying to Dunedin on 20 August 2017. Gaming friend said that, during this visit, they

took the individual to the same shooting club that they visited in 2013. There is no record

of the individual attending the shooting club in August 2017. However, gaming friend and

their parent are recorded as attending the shooting club on 18 and 19 August 2017. Given the

individual was staying with gaming friend and their parent during this time, and the evidence

of gaming friend, we think it is likely that the individual attended the shooting club in August

2017.

5 The individual told friends and family that he chose to live in Dunedin because of its climate,

Scottish heritage and low levels of immigration. He told us that he was also interested in

the architecture. He rented a flat at 112 Somerville Street, Dunedin and started living there

on 24 August 2017. Except for three trips overseas, he lived there until 15 March 2019.

6 The Somerville Street flat was very bare. There was a main bedroom, a second bedroom with

a computer, desk and chair and a lounge with only a bed to sit on.

4.3 Finances

7 When the individual arrived in New Zealand, he had several bank accounts with the

Commonwealth Bank of Australia. These accounts held a large proportion of the individual’s

funds.

Section 15

orders

185

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

8 After arriving in New Zealand, the individual opened two bank accounts with ANZ Bank

(Australian and New Zealand Banking Group) on 23 August 2017 and obtained a debit card.

He primarily used one of his accounts with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia and one of

his ANZ Bank accounts to pay for expenses in New Zealand. When paying for expenses using

his ANZ Bank account, the individual would transfer money from his Commonwealth Bank

of Australia accounts into his ANZ Bank account. The total amount credited to his ANZ Bank

account between 23 August 2017 and 15 March 2019 was $57,018.03. These transfers were

not likely to, and did not, give rise to any suspicious transaction reporting by ANZ Bank.

9 In addition, the individual and Lauren Tarrant had purchased a rental property on

13 January 2017 in New South Wales. The individual received payments from Lauren Tarrant

between March 2017 and March 2019, which represented his share of the rent from the jointly

owned property.

10 Throughout the time he lived in Dunedin, the individual’s living expenses and preparation

for the terrorist attack were entirely funded from the money he received from his father and

income from investments made with that money, including the rental property. We provide

more detail on this later in this Part.

11 The individual gave no concrete indication to anyone of what he would do when the money

ran out beyond indicating to his sister that he might kill himself and later telling family

members and gaming friend that he would go to the Ukraine to live. We have seen no

indication that the individual gave serious thought to working for a living.

12 As will become apparent from the individual’s planning documents, his dwindling financial

reserves influenced the timing of his terrorist attack.

4.4 Associations with others

13 The individual’s social interactions in Dunedin were limited. He had only routine dealings

with his landlord and property manager and little contact with neighbours. His interactions

with people he met at shooting clubs and the gym were superficial. There were also one-off

transactional exchanges with people when buying and selling items online.

14 His association with gaming friend continued. Gaming friend described to us their friendship

with the individual as being “mainly online friends” and referred to him as “just a friend”,

not a good friend. They would be in touch through online gaming up to three times a week

but there were lengthy periods of time (of up to seven or eight months) when there was no

contact at all. As noted, the individual stayed with gaming friend and their family for three

nights when he first arrived in New Zealand in August 2017 and, as well, in January 2018, the

individual and gaming friend travelled to Japan together for two weeks. This was the full

extent of their face-to-face engagement during this period.

Section 15

orders

186

Distressing

Content

15 The individual remained in touch, to a limited extent, with school friend one. In their

statement to the Australian Federal Police, school friend one said that from late 2017

onwards they did not hear from the individual for long periods of time.

16 School friend two was living in Japan in early 2018 and, as we will explain, the individual

met up with them there in January 2018. This was the last time they met, despite

school friend two moving to Queenstown, New Zealand later in 2018. It takes less than

four hours to drive from Dunedin to Queenstown but neither took the time to meet up.

17 The individual remained in contact with his mother and sister. He visited them in Australia

and his mother visited him in Dunedin. Her visit warrants brief discussion. By the time of her

visit (late December 2018 and early January 2019) the individual was starting to finalise his

plan to carry out a terrorist attack and he was fixated on what lay ahead.

18 On 24 December 2018, Sharon Tarrant and her current partner, who is of Indian ethnicity, flew

to New Zealand for a holiday in the North Island. They changed their travel plans so that they

could see the individual in Dunedin from 31 December 2018 to 3 January 2019. During their

visit, the individual took his mother and her partner sightseeing in and around Dunedin and

to Milford Sound, Te Anau and Invercargill. He also took them to the Otago Shooting Sports

Rifle and Pistol Club (which we discuss in more detail below), but they could not access the

range as the individual was unable to unlock the gate.

19 Interactions between the individual and Sharon Tarrant and her partner were awkward and

at times tense. Illustrative of this is an incident on 2 January 2019, when Sharon Tarrant and

her partner took the individual out for breakfast. They went into one café, but soon left after

the individual refused to spend money in “migrant cafés”. He told his mother he wanted

his money going to “white New Zealanders”. They all had to find somewhere else to eat.

Afterwards, they drove back to the individual’s flat in silence.

20 The individual told his mother he would not renew the lease on his flat and wanted to sell his

belongings and move to the Ukraine. That was the last time Sharon Tarrant and her partner

saw the individual before the terrorist attack.

21 Sharon Tarrant later told Australian Federal Police that when she left New Zealand, she felt

“petrified” about the individual’s mental health and increasingly racist views. She felt he

had no friends and had isolated himself in a small, empty flat. She said that she was so

worried that the night she left the individual, she searched online for information about

white supremacy groups in Ukraine. She said that she emailed the individual an article about

extreme right-wing groups in Ukraine that groomed young men like him and pleaded for him

to come home to Australia. He never responded.

187

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

4.5 International travel from New Zealand

22 Between 16 January 2018 and 15 March 2019, the individual left New Zealand three times to

travel overseas. These three trips are detailed in the table below and also shown on a world

map in chapter 3 of this Part.

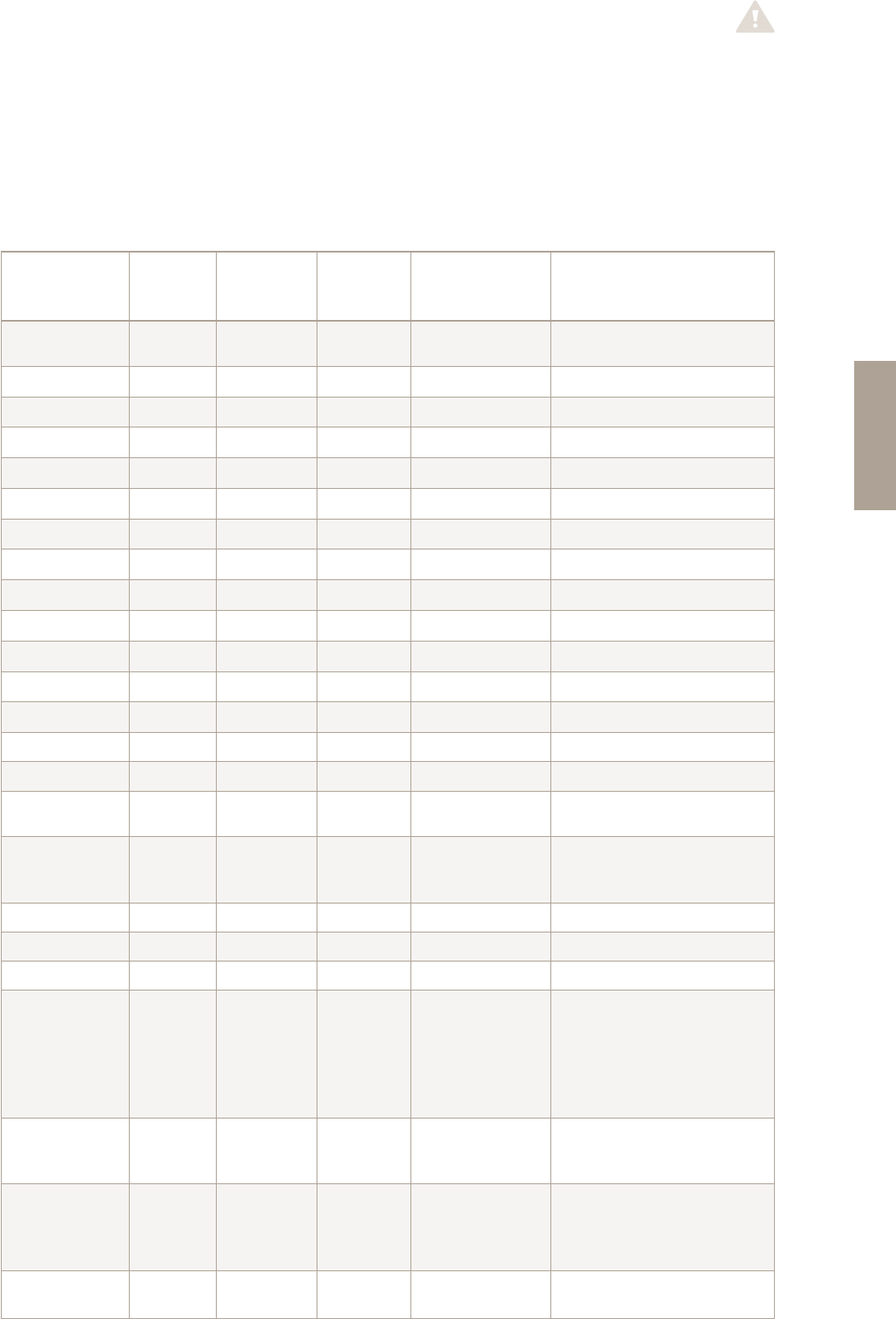

Table 3: The individual’s international travel from New Zealand 2018–2019

Country visited Arrived Departed

Trip 1

Hong Kong (transit) 16 January 2018 16 January 2018

Japan 17 January 2018 30 January 2018

Hong Kong (transit) 30 January 2018 31 January 2018

Trip 2

Australia 30 May 2018 5 June 2018

Trip 3

Australia (transit) 17 October 2018 17 October 2018

United Arab Emirates

(transit)

18 October 2018 18 October 2018

India (transit) 18 October 2018 18 October 2018

Pakistan 18 October 2018 8 November 2018

United Arab Emirates

(transit)

8 November 2018 9 November 2018

Austria (transit) 9 November 2018 9 November 2018

Bulgaria 9 November 2018 15 November 2018

Romania 15 November 2018 26 November 2018

Hungary (transit) 26 November 2018 26 November 2018

Austria 26 November 2018 4 December 2018

Estonia 4 December 2018 5 December 2018

Latvia 5 December 2018 8 December 2018

188

Distressing

Content

Country visited Arrived Departed

Estonia 8 December 2018 10 December 2018

Lithuania 11 December 2018 13 December 2018

Poland 13 December 2018 22 December 2018

United Arab Emirates

(transit)

22 December 2018 23 December 2018

Australia 23 December 2018 28 December 2018

23 The individual’s trip to Japan in January 2018 was with gaming friend. According to gaming

friend, this holiday involved ordinary tourist activities, such as sightseeing. One night they

went out drinking with school friend two, who was working in Tokyo at the time.

24 The individual’s trip home to Australia in May 2018 was for his sister’s 30th birthday. The

individual’s mother described him as being very tense during this visit and unable to relax

at the family gathering.

25 The third trip was between 17 October 2018 and 28 December 2018. The individual spent

the last five days of this trip in Australia. During this time, the individual told his sister and

her partner that he wanted to move to Ukraine as he thought it would be cheaper to live

there and Dunedin was too multicultural. He also met school friend one at a local gym for

a workout. School friend one described this meeting as unremarkable.

26 There is one curious feature of the third trip, which we discuss in chapter 6 of this Part.

Aside from this feature, the international trips taken from New Zealand between January

2018 and December 2018 are not particularly material to our inquiry.

4.6 Internet activity

Attempts to minimise digital footprint

27 The individual took a number of steps intended to minimise his digital footprint so as to

reduce the chances of relevant Public sector agencies, following the terrorist attack, being

able to obtain a full understanding of his internet activity. For example, the individual

removed the hard drive from his computer and this has not been located. He also tried to

delete emails.

Section 15

orders

189

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Facebook

28 Although he became a Facebook member in 2013, the individual’s history on Facebook is

erratic. From time to time he deleted data and removed Facebook friends. And for six

months in 2018 he did not post at all.

29 The individual’s use of his own Facebook page was intermittent, but he occasionally used it to

post far right material. Gaming friend also said that the individual had a number of Facebook

accounts over the last few years, randomly closing one down and creating a new one. In one

Facebook conversation with three Facebook friends, he included a link to an 8chan board,

but the link cannot be recreated.

30 In 2017, the individual joined The Lads Society’s Facebook group, having changed his

username to “Barry Harry Tarry”. Later, he joined The Lads Society Season Two Facebook

page, which was a private group. He made his first post on 19 September 2017. He was an

active contributor, posting on topics related to issues occurring in Europe, New Zealand and

his own life, far right memes, media articles, YouTube links (many of which have since been

removed for breaching YouTube’s content agreements) and posts about people who were

either for or against his views. He also encouraged others to donate to Martin Sellner, a far

right Austrian politician. Two sets of comments warrant particular mention.

31 In early February 2018, the individual (under the Barry Harry Tarry username) engaged in

online discussion with members of The Lads Society Season Two Facebook group about Mein

Kampf.

12

In particular, they discussed Hitler’s suggestion that grievance should be the focus

of propaganda, “galvanising” those who see themselves as persecuted and “drawing in new

sympathisers”. The individual commented:

Agreed, it is far better to be the oppressed than the

oppressor, the defender than the attacker and the political

victim rather than the political attacker. Though 1920’s

Germany was a very different time to now and we face

a very different enemy. Our greatest threat is the

non-violent, high fertility, high social cohesion immigrants.

They will boil the frogs slowly and by the time our people

have enough galvanising force to commit the political and

social change necessary for survival, the demographics in

my opinion will have shifted so harshly that we would likely

never recover.

…

12

Mein Kampf was written by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler in 1925.

Section 15

orders

190

Distressing

Content

What I am saying is that we can’t be a violent group, not

now. But without violence I am not certain if there will be

any victory possible at all.

32 “Boil the frogs” is a metaphor, the premise of which is that if a frog is put into boiling water

it will jump out, but if placed into tepid water that is then brought to the boil slowly, it will

not perceive the danger or change in circumstances, despite being boiled alive. For other

members of The Lads Society Season Two, it would have been clear that the individual was

referring to Muslim migrants when speaking of immigrants and what he said aligns with his

manifesto, The Great Replacement. The assertion that “we can’t be a violent group” was

made around the same time as the first of the planning documents discussed in the next

chapter was created, a document that evidences a clear intention to carry out a terrorist

attack.

33 As we set out in Part 2, chapter 5, those who subscribe to extreme right-wing ideologies

often “tone down” their language to avoid endorsing violence but, at the same time, use

divisive rhetoric towards different ethnic or religious groups. We see the language used by

the individual in the posts as consistent with that used by those on the extreme right-wing.

In addition, ethno-nationalists often implicitly support violence within closed groups. Having

identified the apparent problem of Muslim immigration rates, but offering no democratic

solution, we consider the post by the individual was an implied call to violence and, in this

way, another illustration of his ethno-nationalist beliefs.

34 On 12 February 2018, the individual, still using the Barry Harry Tarry username, made several

posts to The Lads Society Season Two Facebook page. Some we do not reproduce here,

because they contain references to particular individuals and publishing them would give rise

to privacy and safety concerns that cannot be practically mitigated by redaction. The drift of

what he had to say however, emerges clearly enough from the comments that follow:

Across the road from my gym is an Islamic boarding school.

It’s name is ... To date I have just been using it as a source

of rage for my lifts. Today I found out that this Islamic

boarding school that sits in my area was once [a catholic]

school. This is what happens as a society when you fail to

have children then import the children of others to replace

them.

…

191

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Otago Muslim Association [official] was both surprised and

delighted by the announcement. “I’m very, very pleased. It

will be a great asset for the Muslim community in Dunedin,

as well as New Zealand.” What in the fifty fires of fuck have

I stumbled upon here? A … muslim bankrolling an Islamic

learning school in New Zealand? This dude is No.1 on the

prank list.

…

“a non-profit school under charitable status” ... This is

getting backed by tax payers money for sure. Absolutely

sickening

…

Another bankroller was University of Otago [staff member]

and member of the Dunedin Muslim community. ... . The

local university students are being taught ... by a devout

Muslim … . Jesus fucking christ.

Then, after comments from others about Muslim schools:

Though I must say, it is far better to have separate schools

and it ensures they are always seen as outsiders, and

there is no intermixing of cultures or races. Them having

seperate schools is something we should support. Plus it

makes them all gather in one place....JK JK JK

35 In this context, “JK” stands for “just kidding” but is often used ironically (that is by someone

who in fact is not “just kidding”). In this instance, the individual was not “just kidding”.

We know this because he had already completed a planning document that envisaged

mass murder, as we discuss below.

36 When we put these comments to the individual, he acknowledged that the expression, “No. 1

on the prank list” could be seen as a threat of harm. We note that the 15 March 2019 terrorist

attack is sometimes referred to on far right forums as “the mosque prank”. Consistently with

192

Distressing

Content

what seemed to be a general reluctance on his part to acknowledge lapses of operational

security, the individual did not accept that his comments would have been of concern to

counter-terrorism agencies. He thought this because of the very large number of similar

comments that can be found on the internet. Later in the interview, however, he said that

these were the worst of the comments he had posted. We return to discuss this issue in

Part 7: Detecting a potential terrorist.

37 On 9 April 2018, the individual left The Lads Society Season Two Facebook group. Six days

later he deleted 134 Facebook friends, including those made through The Lads Society, such

as Thomas Sewell. For the next six months the individual did not use his Facebook account.

When he did return to Facebook it was in a careful and measured manner. He denied to us

that his April 2018 departure from the group may have been as a result of concerns about the

February 2018 comments, claiming that it was instead due to his social anxiety.

38 He used Facebook Messenger to keep in touch with his family and Facebook friends, and later

on as a method of contacting people to whom he had sold goods online.

39 He reprimanded his mother for using the term “neo-Nazi” in Facebook Messenger when

she commented on his shaved hair and rhetoric. His mother understood that he was not

offended at being called a “neo-Nazi”, but rather was worried that her use of the term on a

popular messaging platform would be detected. Similarly, in a conversation with his sister

on Facebook, the individual expressed concerns about the Australian Security Intelligence

Organisation tracking him and asked her to change names on banking details to anonymise

transactions relating to him. When we interviewed him, he said that there was an element

of play-acting in all of this and that it is common for those on the far right to pretend to

believe that they are under surveillance. This explanation exemplifies the problem identified

in Part 2, chapter 5 – that is, the difficulty in distinguishing between what is ironic and what

is meant literally. We are inclined to see these incidents as evidence of his genuine concern

about operational security.

Other internet activity

40 In a gaming site chat room that gaming friend participated in, the individual posted

numerous links to Reddit posts, Wikipedia pages and YouTube videos. According to

gaming friend these posts were far right in nature. The links have since been deleted.

41 On 17 October 2017, the individual set up a Trade Me account, which he used to purchase

and sell items, including some of his firearms magazines and some firearms equipment

(such as gun slings). The only point of interest in relation to his use of this account is his

username “Kiwi14words”. This is a reference to a white supremacist 14-word slogan, “We

must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children”. This username did

not apparently attract attention.

Section 15

orders

193

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

42 The individual contributed to the NZ Hunting and Shooting online forum. Most of the posts

he made related to the sale of firearms and firearms equipment. Although his exchanges with

others on this forum were at times testy, they are not material to our inquiry.

43 The individual used the internet to buy far right books, ebooks, publications and accessories

to send to his family, such as a “black sun” patch and a Celtic knot necklace with symbols

used by white supremacist groups. The books purchased were Fascism: 100 Questions Asked

and Answered by Oswald Mosley, The Decline of the West by Oswald Spengler and A Short

History of Decay by E M Cioran. These books were delivered to Lauren Tarrant for her partner

(the first listed book) and Sharon Tarrant (the second and third books), possibly to introduce

them to his beliefs. Right-wing publications were also delivered to Lauren Tarrant’s house in

the two years preceding the terrorist attack.

44 A copy of the manifesto written by the Oslo terrorist, a list of the individual’s accounts and

passwords and deleted firearms videos that had been downloaded from the internet were on

the SD card from the individual’s drone. As we will shortly explain, the individual used this

drone to fly over Masjid an-Nur for reconnaissance. We will discuss the possible significance

of the firearms videos in Part 6: What Public sector agencies knew about the terrorist.

45 The individual told us that he had accessed the dark web to make purchases. We know

that he had used Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) when travelling and he told us that he was

familiar with Tor browsers and was thus capable of interacting on the internet in ways that

would make him difficult to trace. He was also familiar with how to encrypt emails.

46 The individual claimed that he was not a frequent commenter on extreme right-wing sites

and that YouTube was, for him, a far more significant source of information and inspiration.

Although he did frequent extreme right-wing discussion boards such as those on 4chan and

8chan, the evidence we have seen is indicative of more substantial use of YouTube and is

therefore consistent with what he told us.

194

Distressing

Content

4.7 Donations to overseas right-wing organisations and individuals

47 While living in New Zealand, the individual made at least another 14 donations to far right,

anti-immigration groups and individuals. Some of these donations were made directly

from the individual’s Australian bank account through PayPal and totalled AU$6,305.78. We

are also aware of five donations made by the individual using Bitcoin. The largest Bitcoin

donation was made on 14 January 2018 and was the equivalent of US$1,377. We have

provided a full list of the donations in the table below.

Table 4: The individual’s donations to overseas right-wing organisations and individuals

while in New Zealand

Transaction date Description as per bank statement Currency Amount

15 September 2017 GENERATION IDENT AUD $187.18

15 September 2017 TRS RADIO AUD $131.02

15 September 2017 PayPal: Rebel News Network Ltd AUD $106.68

15 September 2017 PayPal: SmashCM AUD $177.43

16 September 2017 IMT FR7610278073010002130350147

GENERATIREFC259706626154 EUR

AUD $1,591.09

19 September 2017 GENERATION IDENT AUD $187.36

20 September 2017 IMT FR13907000006276168621321

GENERATIREFC263707054998EUR

AUD $1,590.08

22 December 2017 BACK THE RIGHT AUD $25.97

5 January 2018 MARTIN SELLNER MITU AUD $2,308.97

14 January 2018 Daily Stormer Bitcoin 0.100

12 February 2018 Daily Stormer Bitcoin 0.00865585

12 February 2018 Daily Stormer Bitcoin 0.03

20 April 2018 Identity Movement – Germany Bitcoin 0.00121292

20 April 2018 Identity Movement – Germany Bitcoin 0.00529139

48 As will be apparent, there were multiple donations to the French branch of Generation

Identity – Génération Identitaire (see Part 2, chapter 5), a European far right movement,

and also a donation directly to Identitarian Movement Austria’s leader, Martin Sellner.

13

13

Génération Identitaire refunded the individual AU$1,340.19 on 20 September 2017. Génération Identitaire did not provide

financial support to the individual as this was a repayment of the 16 September 2017 donation. The individual then made a

second donation on 20 September 2017 of almost the same amount as the 16 September 2017 donation.

195

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

49 Following the individual’s donation to Martin Sellner they exchanged several emails in

January 2018. The relevant emails have been provided to us by Bundesamt für

Verfassungsschutz und Terrorismusbekämpfung, the Austrian domestic intelligence agency.

We set out some of the emails below:

Date: 6 January 2018

From: [The individual]

To: Martin Sellner

It’s a small amount to give in relation to the large amount

of work you do. I only wish I could give more. I’m sure

you already know, but I just wanted to tell you personally

you have support from people all over the globe and there

are millions that are relying on you and trust you to fight

for their values. Keep up the great work, it will be a long

road to victory but with every day our people are growing

stronger. Have a great new year, god bless you and god

bless Europe.

Date: 9 January 2018

From: Martin Sellner

To: [The individual]

Thank you that really gives me energy and motivation.

(Just got my second Channel and my 5th bank striked down

in 2018) If you ever come to Vienna we need to go for a café

or a beer. ;)

Date: 10 January 2018

From: [The individual]

To: Martin Sellner

The same extends to you if you ever visit Australia or

New Zealand, we have people in both countries that would

happily have you stay in their homes if you ever visit. If you

are coming to this part of the world at anytime in the near

future you should contact Blair Cottrell … or Tom Sewell

…, both are currently the leaders of a movement similar to

yours that are establishing clubs and activism throughout

most Australian capital cities. Keep fighting the good fight,

[the individual].

196

Distressing

Content

50 We have no evidence that the individual met with either Blair Cottrell or Thomas Sewell

(see chapter 3). In referring to Blair Cottrell and Thomas Sewell in the emails, the individual

was not speaking on their behalf. Instead, it is likely that the individual referred to them in

an attempt to impress Martin Sellner by implying that the individual knew them personally,

when he did not.

51 The individual travelled to Austria and he was there on 9 November 2018 in transit and from

26 November 2018 to 4 December 2018. He told us that he did not meet Martin Sellner

at those times and had not tried to do so. We are inclined to accept this denial. There

is no evidence to suggest they did meet and by this stage we think it unlikely that the

individual would have wished to do anything that might attract the attention of international

intelligence and security agencies.

52 During our interview with him, the individual indicated he had donated to more organisations

than those we have listed. It is distinctly possible therefore that he made donations of which

we are not aware.

197

The terrorist

PART

4

Distressing

Content

Chapter 5: Preparation for the terrorist attack

5.1 The influence of the Oslo terrorist

1 A copy of the Oslo terrorist’s manifesto was found on the SD card associated with the

individual’s drone. There are a number of references to the Oslo terrorist in the individual’s

manifesto. The individual also discussed him when interviewed by New Zealand Police on the

afternoon and evening of 15 March 2019. We see much of what the individual said about the

Oslo terrorist in his manifesto and at interview as trolling and he accepted as much when we

spoke to him. We do, however, consider that the individual was significantly influenced by

the Oslo terrorist and there are two aspects of this that warrant discussion.

2 The first is that the Oslo terrorist’s manifesto and his actions provide considerable

guidance for would-be extreme right-wing terrorists. To a very large extent, the individual’s

preparation was consistent with that guidance. This was evident in his joining a gym and

bulking up with steroids, joining rifle clubs to gain firearms expertise, attempts at operational

security generally, cleaning up electronic devices to try to limit what counter-terrorism

agencies might discover after a terrorist attack and might detract from the “optics” of the

exercise and the preparation of a manifesto to be released at the same time as the attack.

In these respects, the guidance offered by the Oslo terrorist was largely operational in nature.

3 The second aspect of the influence of the Oslo terrorist on the individual’s planning is more

subtle and, indeed, odd. In his manifesto and at his trial, the Oslo terrorist claimed to have

helped re-establish the Knights Templar and to be “Justiciar Knight Commander for Knights

Templar Europe”. The Knights Templar was a Christian military order founded in Jerusalem

in 1119, which was active during the Crusades when there were military struggles between

Christianity and Islam. The original Christian military order was suppressed in 1312. There

are contemporary organisations that have adopted the name “Knights Templar”. But there is

no credible evidence to suggest that an organisation as described by the Oslo terrorist exists.

4 In his manifesto the individual claimed to have “taken true inspiration from Knight Justiciar

[the Oslo terrorist]” and to have received a “blessing” from him “after contacting his brother

knights”. When interviewed by New Zealand Police on the afternoon and evening of

15 March 2019, the individual made similar claims and referred to the “reborn Knights

Templar”. So in this respect there is further commonality between the actions of the

individual and those of the Oslo terrorist. There is also a particular aspect of the individual’s

conduct relating to this claim that we discuss in chapter 6 of this Part.

5.2 Obtaining a firearms licence

5 On 1 September 2017, just 15 days after arriving in New Zealand, the individual took the first

step towards obtaining a firearms licence by paying the application fee. Four days later, he

undertook and passed the required Firearms Safety Course.

198

Distressing

Content

6 He was required to provide two referees (one of whom had to be a near relative) who could

speak to his suitability to possess firearms. The individual identified his sister Lauren Tarrant

and gaming friend as his referees. New Zealand Police did not accept Lauren Tarrant as a

referee because she could not be spoken to in person. In the end, gaming friend’s parent

was added as a referee.

7 On 4 October 2017, a Dunedin-based Vetting Officer visited the individual at his home,

interviewed him and inspected his firearms storage facilities. The Vetting Officer’s

recommendation, based on that interview and inspection, was that the application should be

approved. The individual’s referees were interviewed by a different, Waikato-based Vetting

Officer in their home on 30 October 2017 (gaming friend) and 2 November 2017 (gaming

friend’s parent). Neither of the two referees disclosed anything adverse about the individual.

8 The former Dunedin District Arms Officer approved the licence application on 16 November

2017. There is no record of when the licence was physically issued, but the individual

would likely have received it via post approximately two weeks later. We know he had it

by 4 December 2017 as this was the day he acquired his first firearm. We discuss the firearms