HAL Id: hal-04333632

https://hal.science/hal-04333632

Submitted on 10 Dec 2023

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Copyright

Relative clauses in Romance

Carlo Cecchetto, Caterina Donati

To cite this version:

Carlo Cecchetto, Caterina Donati. Relative clauses in Romance. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of

Linguistics., 2023, �10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-663.�. �hal-

04333632�

1

Relative clauses in Romance

Carlo Cecchetto and Caterina Donati

Summary

Relative clauses are subordinate clauses acting as nominal modifiers. They can be finite or

non-finite in Romance, with finite relative clauses largely more productive and widespread

across varieties. Relative clauses contain an empty position, that can correspond to a gap (as

in most standard varieties) or to a resumptive pronoun, as in Romanian and in many

substandard varieties. In most Romance languages, relative clauses are introduced either by

the invariant element che/que or by some relative pronoun (il quale/lequel/el cual…)

depending on the grammatical function of the variable it refers to.

Keywords:

Relative clauses

Gap

Resumptive pronoun

Complementizer

Wh-element

Free relatives

Reduced relatives

Pseudorelatives

Table of content

1. Some definitions

2. The nature and distribution of relativizers

2.1. Relatives with explicit relativizers

2.2. Reduced relatives

3. The nature of the null element: resumptive strategies

4. The nature of the head

4.1. Free relatives

4.2. Light headed relatives

4.3. Free choice free relatives

4.4. Correlatives

4.5. Pseudorelatives

1. Some definitions

Relative clauses are subordinate clauses whose distribution is not clausal and whose

interpretation is not propositional. They occur where nominal modifiers or full NPs or PPs

occur and receive a similar interpretation. An argument or an adjunct inside the relative clause

is obligatorily “null” (i.e., realized as a gap or as a resumptive pronoun). Relative clauses can

be finite or non-finite in Romance, with finite ones largely more productive and widespread

across varieties. This chapter will mainly focus on the latter, and only briefly describe the

former in a devoted paragraph towards the end (§4.2). The NP that the relative clause

modifies, when it is present, is called the head, or the antecedent of the relative clause (RC).

Relative clauses in Romance are post nominal, in that they follow the head, as

illustrated in (1) in Italian

i

.

2

(1)

Ho

letto

[

NP

il libro

[

RC

che mi

avevi

consigliato [e]]]

have.1SG

read

the book

that me.dat

had.2SG

recommended

‘I read the book you had reccomended to me’

In (1) the RC che mi avevi consigliato modifies the head NP il libro, which is external and

precedes the RC. This configuration is usually referred to as externally headed post nominal

relative clauses. There are no attested internally headed relative clauses in Romance, nor

prenominal ones, therefore we do not discuss them here.

Relative clauses with an external head contain a “null” position related to the modified

nominal phrase. This position can correspond to a gap (as in 1) or to a resumptive pronoun, as

in (2) in Romanian.

(2)

Băiatul

pe

care

îl

vezi

Boy-DEF

PE

who

cl.1SG

see.1SG

‘The boy I see’

In (1), the object position of the embedded verb consigliato (‘recommend’) contains a gap,

which corresponds to the head NP, libro (‘book’). In the Romanian example, the object

position is filled by a pronominal proclitic, which corresponds to the head NP, băiatul (‘boy’).

These two examples illustrate the two main strategies for the realization of the null position of

relative clauses that are attested in Romance, which we will examine in details in § 3.

The position of the null element can vary: the two examples just discussed in (1) and

(2) are cases of object relative clauses, given that the null element is in object position. (3) is a

subject relative clause in Spanish; (4) illustrates an oblique RC in French; (5) a possessive RC

in Catalan. Finally, the example in (6) displays a predicative RC in Portuguese. In all these

examples, the variable corresponds to a gap, as signalled by the notation [e].

(3) Encontré al profesor que [e] escribió este libro.

Met.1SG to-the professor that wrote.1SG this book

‘I met the professor who wrote this book’ Subject RC Spanish

(4) Voici le livre dont je t’ai parlé [e].

Here the book DONT I CL.2SG have.1SG talked

‘Here is the book I told you about’ Oblique RC: French

(5) Vou parlar amb aquella noia el pare de la qual [e] és metge.

Go.1SG talk with that girl the father of the which is doctor

‘I am going to talk with the girl whose father is a doctor’ Possessive RC: Catalan

(6) Não è o homem elegant que era [e].

Not is the man elegant that was.1SG

‘He’s not the elegant man he used to be’ Predicative RC: Portuguese

In some cases, when the modified NP contains a noun that can take an argument, it is only the

presence of this empty position that distinguishes a relative clause from a complement clause,

as illustrated in (7’) in Italian (and 7’’ in English).

(7’) a.

[

DP

la dichiarazione

che il presidente

ha rilasciato

ai

giornalisti]]

the statement

that the president

has released

to=the

journalists

3

(7’’) a. The statement that the president has released to the journalists

b. The statement that the president released the journalists

In (7’) the element introducing the RC or the complement clause, che, is superficially

identical (as is that in English in 7’’’), so that the two structures are ambiguous up to the point

of the position of the object of the verb. This temporary ambiguity and how it is processed on-

line has been recently investigated with respect to Italian RCs (Vernice et al. 2016). See also

Staub et al. (2018) for a similar study on English.

In all the examples reported so far, the head of the relative is a full NP. These are

usually called full relatives or headed relatives, as opposed to free or headless relatives, like

(8) in Italian, which will be discussed in § 4.1.

(8)

Chi mi ama

mi

segua

Who me loves

me

follows=SUBJ

‘Who loves me follows me’

Going back to full relatives, we must distinguish restrictive and appositive relatives. The main

difference is semantic, and has to do with the function of the relative clause with respect to

the head, but it also has some syntactic consequences in Romance.

Restrictive relatives, such as (9) in French, modify the noun and its other modifiers

and contribute a restriction to the nominal denotation. In other words, a restrictive RC

delimits the set of possible objects which the head refers to.

(9) L’étudiant qui a lu le manuel a passé l’expérience

The student who has read the manual has passed the experiment

‘The student who read the manual did the experiment’

The example in (9), for example, presupposes that there is a set of students, and identifies one

of them by saying that the relevant student is the one that read the manual.

Appositive relatives, like (10) in French for example, affect the whole NP, including

the determiner, and they contribute additional secondary information without modifying the

nominal denotation.

(10) L’étudiant, qui a lu le manuel, a passé l’expérience

The student who has read the manual has passed the experiment

‘The student, who read the manual, did the experiment’

The relative clause in (10) does not identify any particular student out of a set, it simply gives

an additional information, namely that this independently identified student read the manual.

As the examples in French above make clear, Romance languages do not exhibit a

clearly separated syntax for restrictive and appositive relative clauses. In (9) and (10) the

difference is prosodic, with a break signalled by the comma in (10) separating the head and

the appositive RC. Some other differences concern the distribution of the various relativizing

elements in the two types of clauses, a point to which we shall go back. When not overtly

specified, all we will say in the rest of the chapter should be interpreted as referring to

restrictive relative clauses.

b.

[

DP

la dichiarazione

che il presidente

ha rilasciato

i

giornalisti]]

the statement

that the president

has released

the

journalists

4

A third type of relative clause has been identified by Carlson (1977), who calls it

"amount relative". This type is superficially similar to a restrictive relative, but it is

semantically distinct in that the head and the relative clause jointly denote not a set of

individuals, but a set of amounts. This interpretation emerges most clearly in examples like

(11), in which the NP modified by the relative denotes an abstract quantity of wine, rather

than a concrete instantiation of wine.

(11) Il nous faudrait une année entière pour boire le vin que Jean a bu l’autre soir.

It us need.1

SG a year complete to drink the wine that Jean has drunk the other night

‘We would need an entire year to drink the wine that Jean drank last night’

No clear syntactic difference distinguishes amount relatives from (other) restrictive relatives

in Romance, and this is why we shall not go back to this type.

Three properties will be discussed in details and will govern the organization of the

article:

- the nature of the relativizer elements, which can be explicit (§ 2.1) or absent, as in

reduced relatives (§ 2.2);

- the nature of the empty element (§ 3);

- the nature of the head (§4).

2. The nature and distribution of relativers

Most relatives in Romance are introduced by some special element that we shall call a

relativizer (§2.1). Reduced relatives, that contain no such element and exhibit an

impoverished participial verb form (§2.2), are an exception.

2.1. Relatives with explicit relativizers

Potentially, the element introducing a RC does at least one of three things:

- signal the subordination clause that follows

- signal the function/position of the null element

- agrees with the head NP.

The traditional way of presenting relativizers in Romance is by portioning them into two

categories: on one hand, the linker che/que and its kin, which are typically uninflected for

case or any other phi-features related to the head and to the null element, and only signals

subordination. On the other hand, a set of pronominal elements more or less homophonous to

interrogative pronouns or wh-elements, typically agreeing in gender and number with the

head noun and carrying along some preposition selected in the gap position.

Starting from Central Romance, and in particular French and Italian, we observe that

the two categories of elements are in strict complementary distribution: in bare positions, only

che/que is possible (with its variant qui in subject position: see below); in oblique positions,

i.e. preceded by a preposition, only wh-elements are possible.

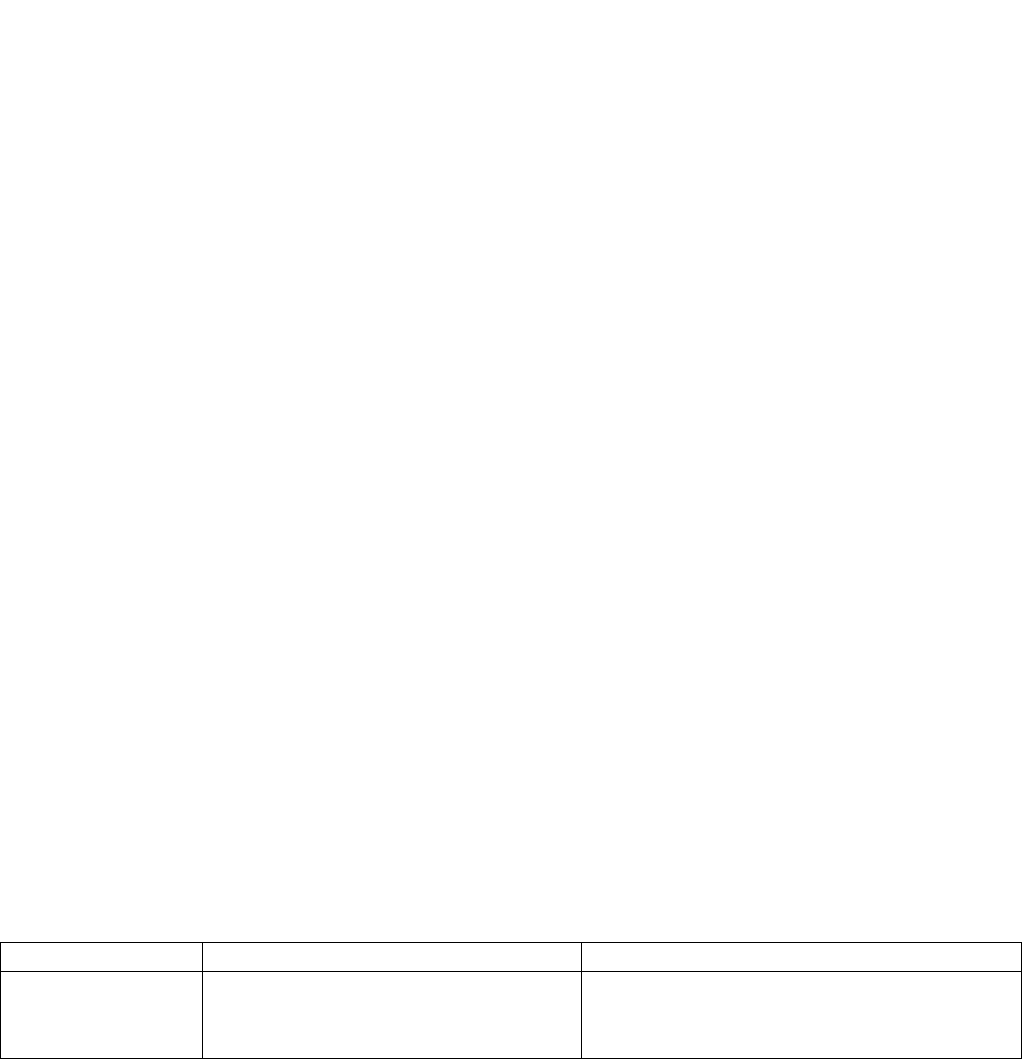

Table 1. The distribution of relativizers in French and Italian

French

Italian

Subject position

‘The letter that

arrived yesterday’

Qui

La lettre qui est arrivée hier

Che

La lettera che è arrivata ieri

5

*le/la quel.le

*La lettre laquelle est arrivée hier

Il/la quale

*La lettera la quale è arrivata ieri

Object position

‘The letter that I

received

yesterday’

Que

La lettre que j’ai reçue hier

Che

La lettera che ho ricevuto ieri

*le/la quel.le

*La lettre laquelle j’ai reçue hier

*Il/la quale

*La lettera la quale ho ricevuto ieri

Oblique

‘The letter about

which I think’

‘The girl about

whom I think’

qui

h

, le/la quel.le

La lettre à laquelle je pense

La fille à qui/à laquelle je pense

cui, Il/la quale

La lettera/la ragazza a cui/alla quale penso.

*Que

*La lettre à que je pense

*che

*La lettera a che penso

Prepositional

‘The letter about

which I told you’

Dont, de le/la quel.le

La lettre dont/de laquelle je t’ai parlé

Cui, il/la quale

La lettera di cui/della quale ti ho parlato

Locative

‘The city where

I’ll go”

où

La ville où j’irai

dove

La città dove andrò

Things are slightly different in Iberian varieties, and in particular Spanish, Portuguese and

Catalan: while the bare form is always and only que, its distribution is not complementary

with the wh-elements in that que is also allowed to a certain extent with prepositions. Some of

examples of this oblique use of que are given in (12) for Spanish and (13) for Portuguese.

(12) a.

El bolígrafo

con (el) que

escribo

todas

mis cartas

The pen

with (the) that

write.1SG

all.fem.PL

my letters

‘The pen with which I write all my letters.'

b.

Un diario

para (el) que

trabajo

a tiempo

completo

A newspaper

for (the) that

work.1SG

at time

full

'A newspaper for which I work full time’

(Brucart 1992: 115)

ii

(13) a.

O cão

a que

Fizeste

festas

Fujiu.

The dog

to that

did.2SG

caresses

fled

‘The dog you caressed fled’

(Brito & Duarte 2003: 663)

b.

O pais

em que eu

vivi

mais tempo

foi

o Japão

The country

in that I

lived.1SG

more time

was

the Japan

‘The country in which I lived longer was Japan ‘

(Veloso 2013: 2088)

c.

A pessoa

com que

o professor

conversou

The person

with that

the professor

talked.1SG

‘The person with whom the profesor is talking’

6

(Rinke and Assmann 2017)

Catalan resembles the other Iberian varieties in allowing some oblique use of a que form.

When preceded by a preposition, however, que is written with a diacritic (què) that is

supposed to signal its tonic status, as opposed to the unstressed nature of the bare que.

(14) a.

El llibre

que vam

llegir

l’any

passat

the book

that PAST.1PL

read

the year

passed

‘The book we read last year’

b.

El llibre

de què

et

vaig

parlar

ahir

the book

of that

CL.DAT.2SG

PAST.1SG

speak

yesterday

‘the book about which I told you yesterday’

(Brucart 1992: 132)

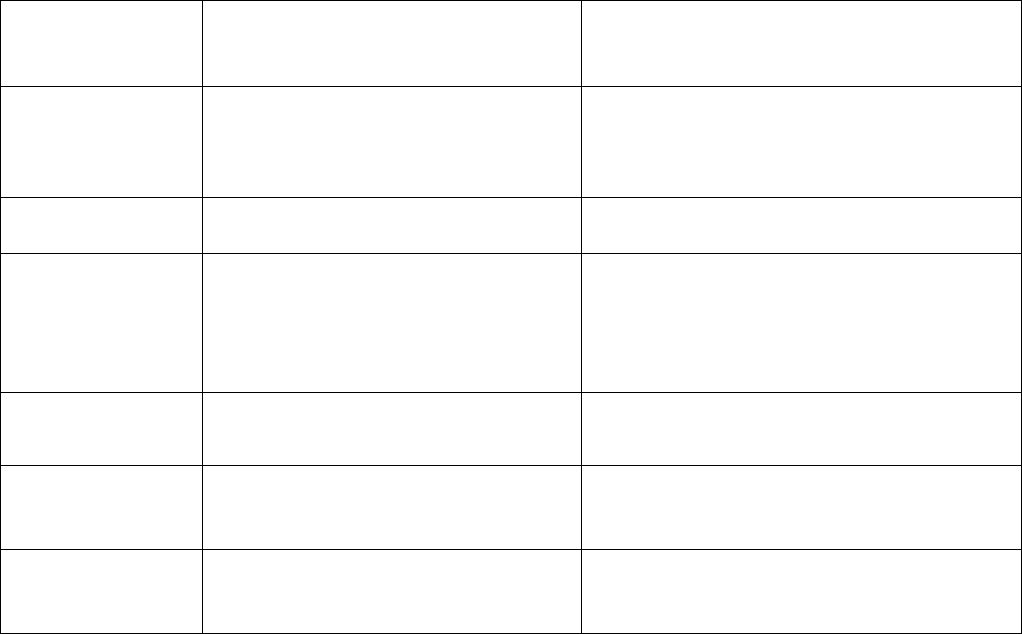

Table 2. Comparing the distribution of ke in French and Italian vs. Spanish, Portuguese and

Catalan.

Subject

object

predicate

oblique

De PP

locative

French/Italian

que

+

+

+

-

-

-

wh

-

-

-

+

+

+

Spanish/Portuguese

que

+

+

+

+

+

+

wh

-

-

-

+

+

+

Catalan

que

+

+

+

+ què

+ què

+ què

wh

-

-

-

+

+

+

Before turning to Romanian, which displays a different pattern, let us focus on the nature of

che/que, which has raised much debate. There are two possible analyses for this element.

According to a first account, che/que corresponds to a wh-element, the wh-element that we

find in interrogatives in all Romance varieties, both alone and used as a wh–determiner akin

to which. According to the second account, che-que is a complementizer. Consider the wh-

element che-que in (15).

(15)a.

Que

vas-tu

faire ?

French

KE

FUT.2SG-you

do

b.

Che

farai?

Italian

KE

do.2SG?

c.

Qué

vas

hacer?

Spanish

KE

FUT.2SG

do

d.

(o) que

vais

fazer?

Portuguese

(the) KE

FUT.2SG

do

e.

Què

vas a

fer

Catalan

KE

FUT.2SG to

do

‘What are you going to do?’

7

Identifying the relative che/que with an interrogative would make the description of Romance

relative clauses very simple: in all cases, the RC is introduced by a wh-element, dislocated at

the edge of the relative clause from its base position where it leaves a gap, possibly agreeing

in its landing site with the head of the construction (see Bianchi 2002 for an overview).

(16) a. La ragazza

i

[ che

iWh

[ho visto [t

wh

]

The girl KE have.1

SG seen

b. La ragazza

i

[ [

PP

con la quale

iwh

] [ho parlato [ t

PPWh

]

The girl with the whom have.1SG talked

However, there are a number of properties of che/que that go against this analysis. The

following examples shows this for Italian: relative que/che is not restricted as for the +/-

human feature while interrogative che/que is –human, at least when used intransitively: (17);

relative che/que cannot be preceded by a preposition, while interrogative che/que can (at least

in some varieties: 18); relative che/que is incompatible with a non-finite clause, unlike the

interrogative che/que (19).

iii

(17) a.

#Che

hai

incontrato?

KE

have.2SG

met

‘What have you met?’

b.

La ragazza

che ho

incontrato

The girl

KE have.1SG

met

‘The girl that I met’

(18) a.

Di che libro

stai

parlando?

Of KE book

are.2SG

talking

‘About what book are you talking’

b.

*Il libro di che

stai

parlando

the book of KE

are.2SG

talking

(19) a.

Non

so

che

fare

not

know.1SG

KE

do.INF

‘I don’t know what to do’

b.

*Cerco

un libro

che

leggere

Search.1SG

a book

KE

read.INF

c.

Cerco

un libro

da

leggere

Search.1SG

a book

from

read.INF

‘I am looking for a book to read’

All these properties support the second account, according to which che/que is more similar to

the complementizer that introduces subordinated inflected clauses. Under this account,

che/que is expected to be invariable and insensitive to phi-features, at least in main Romance

varieties

iv

. The incompatibility of relative che/que with prepositions also follows directly if it

is a complementizer: in most (Romance) varieties, the complementizer is indeed incompatible

with a preposition: (20a) and (20b) illustrate this for Italian and French respectively.

(20) a.

Sono contenta

(*di) che tu

mi

abbia

invitata

Am happy.FEM

of KE you

CL.ACC.1SG

have.SUBJ.2SG

invited.FEM

b.

Je suis contente

(*de) que

tu m’aies

invitée

8

I am happy.FEM

of KE you

CL.ACC.1SG=

have.SUBJ.2SG

invited.FEM

‘I am happy that you invited me’

Even more strikingly, in Spanish, where we have seen that relative que can be preceded by a

preposition, this is also true of the complementizer, confirming the tight relation of these two

elements.

(21)

Estoy contenta

de que tu

me

hayas

invitado

Am happy.FEM

of KE you

CL.ACC.1SG

have.SUBJ.2SG

invited.FEM

‘I am happy that you invited me’

(Donati 1995)

Furthermore, the very language, French, which has an allomorph of que with subject gap (qui)

in relatives, displays the same allomorph for the complementizer que under the same

conditions, as shown in (22)

v

.

(22) a. La revue qui [e] est parue hier

The journal that is appeared.FEM.1SG yesterday

‘The journal that came out yesterday’

b. Quelle revue penses-tu qui [e] est parue hier?

Which journal think.2SG =you that is appeared. FEM. 1SG yesterday

‘Which journal do you think came out yesterday?

A further piece of evidence that seems to push towards an identification of relative che/que

with the complementizer che/que, comes from those varieties that allow so-called Doubly

filled COMP, that is allow for the simultaneous realization at the periphery of the clause of

both a wh-element and a complementizer (an option that is barred from standard European

varieties). An illustration from Quebec French is given in (23).

(23) Je me demande quand qu’il est parti adapted from Bianchi (1999: 220)

I me wonder.1SG when that he is left

‘I wonder when he left’

If bare que/qui were a wh-element, we would expect it to be compatible with the

complementizer que in relative clauses, as appears to be the case in interrogatives (23): but

this is not possible in Quebec French: (24).

(24) *La fille qui que t’aime bien (Kayne 1976 : 275)

The girl that that.CL.ACC.2SG=loves good

‘The girl who likes you’

The ungrammaticality of (24) is expected on the other hand if qui and qui are both

complementizers given that double complementizers are not possible in Quebec French in

general.

For all these reasons the standard analysis has long been that relative che/que is the

complementizer. In its first formulation (due to Kayne 1976), the complementary distribution

of che/que and wh-elements was explained with a deletion operation applying under identity:

when the wh-element is bare, it is identical to the head, and gets thus deleted; when it is

embedded under a preposition, it is not identical to the head and hence cannot be deleted. The

9

complementarity between overt wh-elements and che/que follows from whatever condition is

responsible for the ban on doubly filled COMP in main Romance languages. A modern

version of this analysis is summarized in (25).

(25) a. [ la [

NP

lettre] [

CP

[

NP

Wh-element] que j’ai recue [e]]]

The letter that I=have.1SG received

b. [la [

NP

lettre] [

CP

[

PP

à laquelle] je pense [e]]]

The letter to whom I=have.1SG think

Later other analyses of (Romance) relative clauses have been defended, but all include a

version of this initial assumption, namely that relative que/che is not a pronoun or a wh-

element, but rather the complementizer. This is the case for the null operator analysis put

forward by Browning (1987) for English and largely extended to Romance, where che/que

relatives involve a null Operator which is unable to pied-pied a preposition, as opposed to

full wh-elements. This variant of the analysis is summarized in (26).

(26) a. [ la [

NP

lettre

i

] [[

NP

Op

i

] que j’ai reçue [e]]]

b. [la [

NP

lettre

i

] [[

PP

à laquelle

i

] je pense [e]]]

This is also the case of the various versions of the raising analysis originally stemming from

Vergnaud (1974) and revived in Kayne 1994 (see also Bianchi 1999): under this analysis,

what moves in RC is the head NP itself, and the wh-elements are determiners stranded in

when a PP is moved. A version of this analysis is summarized in (27).

(27) a. a. [ la [

CP/NP

lettre

i

] que j’ai recue [e

i

]]]

b. [la [

CP/NP

lettre

i

] [

PP

à laquelle [e

i]

]

k

[ je pense [e

k

]]]

This is not the place to go into more details assessing the pros and cons of these and other

competing analyses

vi

. Suffice it to mention that more recent proposals led to a reconsideration

of the basic identification of che/que with a complementizer as opposed to a wh-element.

What happened is that many ended up denying the existence of two separate lexical entries

for the wh-element che/que and the complementizer/relative che/que, seeking for a unitary

analysis as a determiner in every context. An obvious advantage of this unification it that it

would be able to explain why all Romance languages display this systematic ambiguity of

che/que elements: see for example Manzini and Savoia (2003); Poletto and Sanfelici (2019);

Kayne (2010) for Italian; Kato & Nunes (2009) for (Brazilian) Portuguese.

As for the Iberian facts, and the possibility of a prepositional que optionally preceded

by a determiner, two analyses seem possible and have indeed been proposed: that the null

operator (optionally lexicalized as a determiner el/o) has no ban on pied piping in those

languages (cf. Brucart 1992); or that there is a (el) que/què relative pronoun beside the

complementizer que, that can move to the edge of the clause pied-piping a preposition (see

Rivero 1980, 1982). This latter analysis seems particularly justified for Catalan, where this

double nature of que/què appears to have some phonological effect.

Turning now to Romanian, restrictive relatives follow a different system in this

language, not displaying any split between bare and prepositional positions in the distribution

of relativizers. In every position, the wh-element care (‘who/which’) is possible, preceded or

not by a preposition, or even inflected for case (dative)

vii

.

(28)

Băiatul

care [e]

cunoaşte

amănuntele

Subject RC

10

boy-DEF

who

knows

details-DEF

‘The boy who knows the details.

(29)

Băiatul

pe care [e]

îl

vezi

Object RC

boy-DEF

PE who

CL.1SG

see.2SG

‘The boy whom you see’

In (29) notice that an object clitic is obligatory in the position of the null element. The same is

true in dative relative clauses, as illustrated in (30). We shall come back to this feature in the

next section (§3).

(30)

Arată-mi mama

Căreia

fata îi

dă

o floare

Dative RC

Show-me mother

which.DAT.FEM.SG

girl CL.DAT

gives

a flower

‘Show me the mother to whom the girl gives a flower.’

Alongside this unmarked strategy, Romanian also marginally allows a complementizer

construction, with the invariable element ce, and once again this is restricted to bare positions,

suggesting a strong parallelism with the pattern just described for che/que. In Romanian

however it obligatorily involves a resumptive pronoun (Dobrovie Sorin 1994 : 214).

Before turning to the nature of the null element, a short notice on appositive relative

clauses: in all Romance languages the more or less strict complementarity between che/que

and wh-elements that we have just described does not hold in appositives, where a bare wh-

element is systematically available: this is probably the main syntactic property teasing apart

appositive from restrictive RCs on a superficial level.

2.2. Reduced relatives

Reduced relatives (also called participial relatives) are relative construction that are spread

across Romance varieties and contain a verb phrase modifying a head noun. They are reduced

because they do not contain either a complementizer of the che/que type or a relative pronoun

and because they present a verbal form that is not fully inflected for tense, typically a past

participle. (31b) is a reduced relative that corresponds to the full relative in (31a).

(31) a. Le philosophe qui a été admiré par Marx French

The philosopher that has been admired by Marx

b. Le philosophe admiré par Marx

The philosopher admired.PART-MASC by Marx

‘The philosopher admired by Marx’

The distribution of reduced relatives is more constrained than that of full relatives. To begin

with, they can only be subject relatives, never object relatives (cf. 32).

(32) a. Le philosophe qui a admiré Marx

The philosopher that has admired Marx

b. * Le philosophe admiré Marx

The philosopher admired.PART-MASC Marx

As extensively discussed in a literature stemming from Burzio (1986), reduced relatives in

Romance are grammatical only with certain types of predicates. In particular, Burzio (1986)

11

showed that, at least in Italian, reduced relatives are grammatical with passive (cf. 33) and

unaccusative (cf. 34) verbs, while they are totally out with unergative verbs (35).

(33) La ragazza amata da Gianni

The-

FEM girl-FEM loved.PART-FEM by Gianni

‘The girl loved by Gianni’

(34) Il ragazzo arrivato ieri

The-MASC boy-MASC arrived. PART-MASC yesterday

‘The boy arrived yesterday’

(35) *Il ragazzo starnutito ieri

The-

MASC boy-MASC sneezed PART-MASC yesterday

The context in which reduced relatives are allowed in Italian are exactly those in which the

past participle combines with auxiliary ‘be’. This may not be coincidental. In fact, Iatridou,

Anagnostopoulou, and Izvorski (2001) claim that across all Indo-European languages reduced

relatives cannot contain a past participial if the missing auxiliary is ‘have’. Although this

generalization is fairly solid, they point out an exception in Spanish. Reduced relatives are

possible for (possibly a subset of) unaccusatives, even if unaccusatives take ‘have’ as an

auxiliary in this language.

(36) Las chicas [recen llegadas a la estacion] son mis hermanas

The girls [recently arrived.

FEM.PL at the station] are my sisters

‘The girls who have just arrived at the station are my sisters.’

3. The nature of the null element: resumptive strategies

As for the realization of the null element contained in the RC, we have seen that there are two

possibilities:

1. a gap

2. a resumptive pronoun

In most standard European varieties, with the exception or Romanian, the gap strategy

is the unmarked, or “conventional” option, the only one that is acknowledged by normative

grammars. All Romance languages do exhibit however a (possibly non-standard) alternative

strategy including che/que and a resumptive pronoun, at least in some relativisation positions.

In this section, we shall have a look at the distribution of these resumptive strategies across

Romance varieties.

Before proceeding, let us clarify a point: what we are going to talk about is what Sells

(1994) calls “real” resumptive pronouns, namely pronouns that are constrained language-

specifically and have a clear grammatical distribution. We shall not consider another type of

resumptives, that Sells calls “intrusive”, and that are only possible across languages as a last

resort strategy in configurations where a gap would be ungrammatical. An example of such

intrusive pronoun is given in (37) for Italian.

(37) Questo è il ragazzo che il poliziotto che l’ha picchiato deve essere sospeso

This is the guy that the cop that CL.1SG=has beaten must be suspended.

‘This is the guy that the cop who beat him up must be suspended.

(Beltrama and Xiang 2016:8)

12

Given their last resort and partially language independent availability, we will not discuss

intrusive pronouns any further.

Returning to real resumptives, Brasilian Portuguese is an example of a Romance

variety other than Romanian where the resumptive strategy has become the norm and exhibits

a strict distribution: all oblique positions are realized through invariable que and an obligatory

resumptive; the resumptive is optional in object position and is ungrammatical in subject

position.

(38) a. O homem que (*ele) ama a Maria (Subject)

the man that (he) loves the Maria

'the man who loves Maria'

b. O homem que eu vi (ele) (Object)

the man that I saw (him)

'the man that I saw’

c. O homem que eu vi a mulher d’*(ele) (possessive)

the man that I saw the wife of-him

'the man whose wife I saw’

d. O homem que eu conversei com *(ele) (Oblique)

the man that I talked with (him)

'the man that talked with'

(Grolla 2005)

A pattern very similar to the one just illustrated in Brazilian Portuguese is not extraneous

from European varieties either. Across all varieties, at a more or less substandard or colloquial

register, a similar che/que plus resumptive construction is a productive strategy alternative to

“conventional” construction involving pied piping of the wh-element described in the

previous section (Suñer 1998).

Some examples from Italian and French are reported below (Italian examples from

Mulas 2001; French examples from Zribi-Hertz 1984 and Gadet 1989:3, quoted in

Cardinaletti and Guasti 2003).

(39) Italian

a. Indirect object

Sono un tipo che gli piace rischiare

Am a type that

CL.1SG.DAT pleases risk.INF

b. Locative

E’ una libreria che ci vado ogni tanto

Is a bookstore that CL.LOC go.1SG sometimes

c. Other obliques

E’ il coltello che ci ho tagliato la torta

Is the knife that CL.LOC have.1SG cut the cake

d. Possessive

Il dirigente che la sua fabbrica ha chiuso qualche mese fa

The leader that the his factory has closed some months ago

(40) a. subject

Voici le courier qu’il est arrivé ce soir

Here the mail that CL.NOM. 1SG is arrived tonight

b. indirect object

Voici l’homme que Marie lui a parlé

13

Here the man that Marie CL.DAT.3SG has spoken

c. Other obliques

Voici la maison que Marie y pense encore

Here the house that Marie

CL.LOC think.3SG still

d. Possessive

La femme que son mari est mort hier

The woman that her husband is died yesterday

Some more scattered examples in Catalan (Hirshbühler and Rivero 1981: 596) and in Spanish

(Vicente 2004) are given blow.

(41) Es un riu que s'hi ha negat molta gent.

is a river that CL.LOC have3SG drowned many people

(42) La persona que los apuntes son suyos puede pasar a recogerlos

the person that the classnotes are his/hers can come to pick-up-

CL.3PL

‘The person who owns the class notes can come to pick them up’

In general, clear quantitative data are not available on the distribution of the

resumptive strategy in Romance, but a number of observations support the conclusion that it

is commonly used in spoken colloquial language by people of different socio-economic

backgrounds, while it is avoided in written texts and in more formal discussion

viii

. To give an

example, Berruto (1980) studied a corpus of Italian spoken in Emilia and found that 30% of

object relatives and 79% of indirect object and genitive relatives contained a resumptive

pronoun. Among locative relatives, 53% contained a resumptive element, either a preposition

(18%) or a clitic pronoun (35%).

While the resumptive strategy is often presented in normative grammars as an

incorrect and corrupt usage, it goes back as far as Late Latin, only starting to be stigmatized in

the XIV century (Hirshbühler and Rivero 1982; Auger 1993). Its robustness might correlate

with the relative marked status of the ‘il/la quale’/’Le/la quel.le’ forms, scholarly formations

that never became the unmarked elements in natural everyday language. In an interesting

elicitation study, Cardinaletti and Guasti (2003) show that French and Italian children avoid

wh-relatives with a preposition and rather opt for resumptive che/que-relatives up to the age

of 10. Cardinaletti and Guasti suggest that prepositional wh-relatives may be the result of

educational pressure.

As for the exact distribution of the resumptive across the various relativisation

positions, Romance languages seem to differ: while the resumptive seems to be obligatory or

at least largely preferred in prepositional positions, its availability in bare positions vary. In

subject position, in particular, a resumptive seems grammatical only in some varieties, as in

French (Gadet 1989; see 43), in European Portuguese (Alexandre 2000: see 38), and in

Peruvian Spanish (Cerrón Palomiño 2015), but not in the other (major) Romance languages,

including Romanian and Brasilian Portuguese.

(43) Voici le courier qu’il est arrivé ce soir

Here the mail that=CL.NOM.1SG is arrived tonight

‘Here the mail that arrived tonight’

(Gadet 1989)

(44) Eu estou a extrair de um domínio [ que ele próprio não é regido]

I stay.1SG to estract from a domain that it really not is governed

14

‘I am about to exit a domain that is really not governed’

(Alexandre 2000)

But even in oblique positions, where the resumptive pronoun is largely preferred with

che/que, it is not exceptional to find a gap, as in the examples in (45), where the prepositional

information is lacking for good.

(45) a. Italian

Non c’è niente che ho bisogno

Not there=is nothing that have1.

SG need

‘I do not need anything’

(from Sono un ragazzo fortunato, song by Jovanotti 1992)

b. French

C’est le livre que je t’ai parlé hier

It=is the book that I

CL.DAT.2SG =have.1SG spoken yesterday

‘This the book I talked to you about’

Which factors favour resumption over gap strategies in the various relativisation sites (which

might include simple distance and other parsing complexity features), and what is the exact

status and frequency of non-standard che/que-strategies are issues that require further

research.

4. The nature of the head

All the examples we have discussed so far contain a clearly identifiable nominal phrase

modified by a separate RC following it. These are all cases of fully headed relatives. In other

cases, the head is either absent, as in free relatives (§4.1), or very reduced, as in light headed

relatives (§4.2). Other special cases are free choice wh-constructions (§4.3), correlatives,

where the head is repeated twice, (§4.4) and pseudorelatives (§4.5).

4.1. Free relatives

Free relatives can be preliminarily defined as relative clauses that are introduced by a bare

wh-element and do not show any (overt) head (see below for special cases for so-called free

choice free relatives that do not fit this working definition). Prototypical examples of free

relatives in English are given in (46) and (47) in square brackets.

(46) I noticed [what you did for me]

(47) I did not meet [who you recommended]

Typically, the same sequence of word that forms a free relative can form an embedded

question:

(48) I wonder [what you did for me]

(49) I wonder [who you recommended]

15

Free relatives can also have an adverbial distribution, as in (50). In this case they are also

referred to as ‘adverbial clauses’.

(50) a. I arrived [when you left]

b. I cooked the dish [how you suggested]

c. I went [where you did]

Free relatives are present in all major Romance varieties, as exemplified below.

(51) a. [Chi arriva in ritardo] non partecipa alla riunione

‘Who arrive 3.SG in=late not take=part3.SG to=the meeting’

‘Who will arrive late will not take part to the meeting’

Italian

b. [Qui diu aixo] ment

‘Who say3.SG this lie3.SG’

‘Who says this lie’

Catalan (Hirschbühler & Rivero 1983: 487)

c. [Quien bien te quiere] te hara llorar

who well you.

ACC love.3.SG you.ACC make3.SG.FUT cry

'Who loves you well will make you cry’

Spanish (Rivero 1984: 83)

d. Elena detestă [pe cine o critică].

Elena hate3.SG ACC who her criticize3.SG

‘Elena hates the one/those who criticize(s) her.’

Romanian (Caponigro and Fălăus 2017)

d. Quem estuda tem boas notas

‘Who study3.SG has good marks’

‘Who studies has good marks’

Portoguese (Mioto and Lobo 2016: 282)

e. Je féliciterai [ qui relèvera le défi]

I congrat1.SG.FUT who take3.SG.FUT the challenge

‘I will congrat (the one) who will take the challenge up.’

French

Free relatives in Romance are distinguished from headed relatives not only by the absence of

an overt head but also by the fact that, unlike headed relatives, they cannot contain the

counterpart of the complementizer che/que. In fact, the sentences in (51) become

unacceptable if the complementizer is introduced.

As for wh-words that can introduce free relatives in Romance varieties, there is some

cross-linguistic variation. For example in standard Italian free relatives can be introduced by

chi (’who’), dove (’where’), quando (’when’), come (’how’), quanto (‘how’) but not by cosa

(’what’).

(52) a. Ho chiesto cosa hai letto

have.1SG asked what have.2SG read

‘I asked what you read’

16

b. *Ho comprato cosa hai letto

have.1

SG bought what have.2SG read

Italian is not isolated in ruling out the counterpart of ‘what’ in free relatives. Also in French,

Portoguese, Spanish and Catalan free relatives cannot be introduced by the equivalent of

‘what’.

(53) *J’aime [que tu as cuisiné].

I like KE you have.2SG cooked

French

(54) *He tastat [què has cuinat].

have.1SG tasted what have. 2SG cooked

Catalan (Caponigro 2003:163)

(55) *Comí [ qué cocinaste].

ate.1

SG what cooked.2SG

Spanish (Caponigro 2003:168)

(56) *Ele admira [que é belo].

He admire.3

SG what is beautiful.MASC.SG

‘He admires what is beautiful.’

Catalan

In other Romance varieties, like Romanian, free relatives with the counterpart of ‘what’ are

fully acceptable, though:

(57) Ți-am dat [ce vrei]

CL.DAT.2SG=have.1SG given what wanted.2SG

‘I gave what you wanted’

Romanian

A significant part of the literature on free relatives has been devoted to the matching

requirement, another property that sets free relatives and headed relatives apart. In the case of

Romance the matching requirement can be stated as a condition that dictates that the

preposition introducing the wh-phrase has to be compatible both with the matrix predicate and

with the predicate in the free relative. Matching is illustrated in (58). As the verbs concordar

‘agree’ and conversar ‘talk’ both select for the preposition com ‘with’, the sentence obeys the

matching condition.

(58) Ele só conversa com quem ele concorda.

he only talk.3SG with who he agree.3SG

‘He always talks to whoever he agrees with.’

Brasilian Portoguese (Kato and Nunes 1998)

However, (59) and (60) are ruled out since the verb rir ‘laugh’ selects for the preposition de.

Therefore, there is bound to be a mismatch: if the preposition com introduces the wh-word the

selection requirement of the embedded verb rir are not satisfied (cf. 59). If the preposition de

introduces the wh-word, it is the selection requirement of the matrix verb concordar that is

not satisfied (cf. 60).

(59) *Ele sempre concorda com ele ri.

17

he always agree.3SG with he laughs

(60) *Ele sempre concorda de quem ele ri.

he always agree.3

SG of who he laughs

Brasilian Portoguese (Kato and Nunes 1998)

There are syntactic contexts in Romance in which the matching requirement has been argued

not to hold. For example, Hirschbühler and Rivero (1983: 509) claim that in Catalan the

requirement is suspended if the free relative is left-dislocated. Still, cases of mismatch seem

very restricted and the sentences with mismatch often have a marginal status (cf. Grosu 1994

for discussion).

Semantically, free relatives come in two main varieties (cf. Šimík to appear for an overview

of the literature of the semantics of free relatives). They can have the semantics of definite

NPs, namely they denote the unique/maximal entity that satisfies the description that the free

relative provides (this is the only possible way to interpret free relatives in English). For

example, the following sentence can be paraphrased by saying that I reproached all people

who arrived late.

(61) Ho sgridato chi è arrivato tardi.

have.1SG scolded who is arrived late

‘I scolded who arrived late’

Although the unique/maximal interpretation is the typical one, free relatives in many

languages (including all the major Romance varieties) can also have an existential

interpretation, for example when they appear in the complement position of existential be and

existential have predicates (cf. Caponigro 2003, Grosu 2004 and Šimík 2011) This is

illustrated by the following Italian examples. The existential nature of the free relatives is

made explicit by their English translation.

(62) Ho con chi chiacchierare mentre aspetto

have.1SG with whom to-chat while wait.1SG

‘There is someone I can chat with while I am waiting’

(63) C’è chi può aiutare

There=is who can.3SG help

‘There is someone who can help’

As for their syntactic analysis, free relatives have been the object of an extensive

debate that cannot be summarized in a limited space (cf. van Riemsdijk 2006). Suffice it to

say that two families of analyses can be identified. According to a first approach, the free

relative is only superficially headless since there is an empty head that acts as a covert head.

This analysis minimizes the difference with headed relatives (cf. Grosu 2003 for an extensive

defence of this view). According to a second group of analyses, the wh-element is directly

selected by the matrix verb, so free relatives are literally headless. An example of this

approach is Donati’s (2006) account, which claims that the wh-word moves as a head into a

dedicated position in the left periphery and by doing so, it endows the clause with the D-

feature required for its nominal interpretation. Donati’s analysis has been incorporated into

Cecchetto and Donati’s (2015) general theory of labeling, according to which words (but not

phrases) have the power to change the label of the category they attach to. This would explain

why free relatives cannot be introduced only by wh-phrases (as opposed to wh-words), as

illustrated in (64) with an Italian example:

18

(64) *[Quale ragazzo arriva in ritardo] non partecipa alla riunione

which boy arrive.3

SG in late not participate.3SG to=the meeting

a wh-word can turn a clause into a nominal constituent while a wh-phrase cannot.

The generalization that free relatives can be introduced only by wh-words seems to be

very solid inside and outside Romance. However, Romanian is an exception:

ix

(65) Am citit [ ce carte / ce cărți ai citit şi tu].

have.1SG read what book / what books have.2SG read also you

‘I read what book(s) you read.’

Caponigro and Fălăuş (2017)

4.2. Light headed relatives

The impossibility of free relatives introduced by the counterpart of ‘what’ in the

varieties in which this is not possible can be loosely related to the presence of an alternative

construction which resembles (but is distinct from) free relatives. This is the structure that

Citko (2004) called light-headed relatives, where the head has the shape of a demonstrative

pronoun or of a definite determiner and the element che/que is present:

(66) He visto a la [que me presentaste]

have.1SG seen at the that CL.DAT.1SG introduced.2SG

‘I have seen the one that you have introduced to me’

Spanish (Citko 2004: 97)

(67) Ho comprato ciò che mi hai suggerito

Have.1SG bought that that CL.DAT.1SG have.2SG recommended

‘I bought what you suggested’

Italian

(68) He tastat el [que has cuinat].

have.1SG tasted the that have.2SG cooked

‘I tasted what you cooked.’

Catalan (Caponigro 2003:164)

(69) Ele admira [o que é belo].

he admire.3SG the that is beautiful

‘He admires what is beautiful.’

Portoguese (Matos and Brito 2008: 310)

Light-headed relatives and free relatives, although functionally very similar, cannot be

assimilated because light-headed relatives lack two distinctive features of free relatives: they

are not introduced by a wh-word and they do have a head, although this is reduced. Typically

light-headed relatives, unlike free relatives, are not string ambiguous with embedded

interrogatives. However, this is not true in general. For example, in French the sequence

formed by the demonstrative ce and by the complementizer que can introduce an embedded

question (70a) in addition to its use in a light-headed relative (70b):

19

(70) a. Je voudrais savoir [ce que tu as acheté]

I want.1

SG.COND know this that you have.2SG bought

‘I would like to know what you bought’

b. Je voudrais acheter [ce que tu as acheté]

I want.1SG.COND buy this that you have.2SG bought

‘I would like to buy what you bought’

4.3. Free choice free relatives

Another construction that closely resembles (and that according to some authors should be

assimilated to) ordinary free relatives is so-called free choice free relatives. As we mentioned

at the end of §4.1, in the overwhelming majority of cases, free relatives cannot be introduced

by a wh-phrase (as opposed to a wh word). However, if the wh-root attaches to the affix which

corresponds to English –ever, the structure becomes grammatical. This construction is often

called free-choice, due to its semantics. Free choice free relatives have been studied in Italian

(cf. Donati & Cecchetto 2011 and Caponigro and Fălăuş 2017), Romanian (cf. Caponigro and

Fălăuş 2017), and Spanish (Quer 1999) for Romance. The following examples illustrate

Italian (with suffix –unque) and Romanian (with prefix –ori).

(71) [Qualunque ragazzo arriverà in ritardo] non parteciperà alla riunione

Whichever boy arrive.3SG.FUT in late not participate.3SG.FUT to=the meeting

‘Whatever boy will arrive late will not take part to the meeting’

(72) Elena detestă [ori-ce coleg o critică ].

Elena hate.3SG ori-what colleague cl.ACC criticize.3SG

‘Elena hates any colleague that criticizes her.’

Romanian, Caponigro and Fălăuş (2017)

Free-choice free relatives are set apart from ordinary free relatives not only by their semantics

but also by their syntactic properties, as originally discussed by Battye (1989) for Italian. For

example, while che/que is totally unacceptable in ordinary free relatives, it is allowed (or even

obligatory) in free-choice free relatives, at least in some varieties. We report here examples

from Spanish and Italian. As noted by Quer (1999), the subjunctive (or an irrealis) mood is

required to make these sentences fully acceptable.

(73) Presenta’m [qualsevol que hagi fet una solicitud]

Introduce.IMP.SG=CL.ACC-1SG anyone that have-SUB.1SG made an application

‘Introduce to me anyone who has applied’

Catalan (Quer 1999: 76)

(74) Informarán a quienquiera que lo solicite

Inform.FUT.3PL a whoever that CL.ACC ask.SUB.PRS.1SG

‘They will inform whoever asks about it’

Spanish (Quer 1999: 76)

(75) Correggi [ qualunque parola che venga scritta male]

Correct.IMP.SG whichever word that come.SUBJ.3SG written incorrectly

20

‘Correct any word that will be written incorrectly’

Italian (adapted from Battye 1989)

A second difference is that the wh-word that introduces a free-choices free relative can stay

alone as an argument (cf. (76) which sharply contrasts with (77), containing a wh word

without the –unque suffix).

(76) L’opposizione cerca il voto di chiunque

The opposition seek.3-

SG the support of whoever

‘The opposition is seeking everyone’s support’

(77) *L’opposizione cerca il voto di chi

The opposition seek.3-SG the support of who

4.4. Correlative relatives

Correlative relativization strategies typically include a left-peripheral relative clause that is

linked to a nominal correlate in the main clause (Lipták 2009). An illustrative example is

given from Hindi perhaps the most well-known and most cited example of a correlative,

from Srivastav (1991: 3a) : (78).

(78) [jo laRkii khaRii hai ] vo lambii hai

REL girl standing is that tall is

lit. Which girl is standing, that is tall.

'The girl who is standing is tall.'

In Romance correlatives are attested only in Romanian (Brasoveanu 2012), where they

strongly resemble extraposed free relatives. An example is given below (adapted from Bîlbîie

2016: 50).

(79) Care vine primul, acela va câstiga concursul

Who come3-sg first this go3-sg win competition.DEF

lit. who comes first, that wins the competition

‘The person who comes first wins the competition’

4.5 Pseudorelatives

Pseudorelatives are adnominal clauses that are string identical with the headed relative clauses

introduced by che/que but are structurally distinguished from them and have a different

semantics. An example of a pseudorelative is given in (80). As shown by its translation, the

semantics of a pseudorelative is similar to that of Accusative-ing clauses in English, namely

infinitival clauses following perception verbs, like ‘I saw him crossing the street’.

(80) Vi o Jorge que comia a maçã.

21

saw.1SG the Jorge that ate an apple

‘I saw Jorge eating an apple’

(European Portuguese)

(80) cannot be a restrictive headed relative, because restrictive relatives do not modify a

proper name and is not an appositive relative either, because it does not have the intonation of

appositives and because it has a distinct meaning (roughly speaking it means ‘I saw Jorge

while he was eating an apple’).

Pseudorelatives are attested in all major Romance varieties but for Romanian, and

seem to have similar properties, although a systematic comparison across Romance varieties

has not been done yet. Some differences between restrictive relatives and pseudorelatives are

listed below:

(i) Only pseudorelatives appear freely with proper names or pronouns:

(81) L’ho visto che correva (Italian)

CL.ACC.3SG=have.1SG seen that ran

‘I saw him running’

(ii) Pseudorelatives are grammatical only if the antecedent corresponds to the subject of the

pseudorelative, as shown by the contrast between (82) and (83). Object and oblique

pseudorelatives are never acceptable:

(82) J’ai vu Pierre qui embrassait Marie (French)

I =have.1SG seen Pierre that kissed.3SG Marie

(83) *J’ai vu Pierre qui Marie embrassait

I =have.1SG seen Pierre that Marie kissed.3SG

(84) *J’ai vu Pierre à qui Marie parle.

I =have.1SG seen Pierre to whom Marie speaks

(iii) While in ordinary relative clauses there are no restrictions relating the tense of the RC to

that of the matrix clause, tense variation in pseudorelatives is more constrained. For example,

a future tense in the pseudorelative is not grammatical if the matrix tense is present perfect.

(85) Ho visto il ragazzo che correrà. (Italian)

Have.1SG seen the boy that run.FUT.3SG

‘I saw the boy that will run.’

(86) *Ho visto Gianni che c orrerà.

Have.1SG seen Gianni that run.FUT.3SG

(iv) Pseudorelatives are restricted to stage level (namely very transitory) properties. For

example, (77) is ungrammatical because ‘being a student’ is an individual level (namely a

more permanent) predicate.

(87) *Vi a Juan que era estudiante (Spanish)

saw.1SG to Juan that was student

(v) Pseudorelatives are selected by a subset of predicates and therefore have a much more

limited distribution than ordinary headed relatives. These predicates typically include verbs of

perception (‘see’, ‘listen’, etc.); propositional attitudes verbs like ‘imagine’ , ‘remember’;

22

verbs of creation like ‘describe’, ‘draw’ ‘to make a photo of’ etc.; verbs like ‘meet’, ‘find’,

‘leave’; the presentational copula; psych verbs like ‘hate’, ‘(dis)like’ etc.

As discussed by Casalicchio (2013), in some Romance varieties like Spanish,

pseudorelatives alternate with gerundive clauses, as illustrated in (88). Although functionally

similar, gerundive clauses do not have the make-up of relatives, most notably because the

verb is not finite and the che/que category is absent.

(88) Vi a Juan tocando la guitarra

saw.1

SG to Juan playing the guitar

‘I saw Juan playing the guitar.‘

(Spanish)

Pseudorelatives are also functionally similar to infinitive constructions, as the following

examples from Raposo (1989: 304), show. However, their internal make-up and their

distribution is different. For example, infinitival adnominal clauses are restricted to perceptual

verbs while pseudorelatives occur with a bigger group of predicates, as mentioned above.

(89) Vi o Jorge que comia a maçã.

saw.1SG the Jorge that ate-3SG the apple

(90) Vi o Jorge a comer a maçã.

saw.1SG the Jorge to eat the apple

I saw Jorge eating an apple

(European Portuguese)

The literature on pseudorelatives is fairly extensive and we cannot summarize the various

analyses that have been proposed. For further discussion: Cinque (1995), Guasti (1988),

Casalicchio (2013), Radford (1975). Grillo and Costa contain a discussion of pseudorelatives

from a psycholinguistic prospective.

Further Readings

A list on further readings on relative clauses should probably start form the State of the Art

article on relativization by Valentina Bianchi that appeared in Glotta international in 2002:

somehow outdated, it is still the most informative and complete introduction to formal

approaches to relative clauses, with important references to Romance. Another reference

work for further understanding the debate over relative clauses is the volume edited by

Artemis Alexiadou, Paul Law, André Meinunger and Chris Wilder on The syntax of Relative

Clauses, and in particular the introduction by the editors. A third important starting point on

relativization in general is Andrews (2007), which provides a basic typological overview that

might help inserting Romance strategies into a wider picture.

Concerning the analysis to be given to relative clauses, Romance relatives have always

been at the center of the debate. They are crucially related in particular to the development of

the raising analysis, from its very first formulation (Vergnaud 1974; to its more recent revival

by Kayne 1994): see in particular Bianchi (1999). See also Borsley (1997) for an important

critique of the raising analysis and de Vries (2002). A development of the raising analysis

largely based on Italian and Romance is Donati and Cecchetto (2011), further developed in

Cecchetto and Donati (2015). Recent work by Cinque, importantly but not exclusively based

on Romance within a typological perspective, is going towards a unification of the raising

analysis and the matching analysis, and arguing for a universal prenominal origin of relative

23

clauses: see in particular Cinque (2013) and Cinque (in preparation).

On the nature of resumptive pronouns, we recommend the reading of Demirdache

(1991) and of the comprehensive volume edited by Rouveret (Rouveret 2011). See also Suñer

(1998) on resumptive strategies in Romance crosslinguistically and Contreras (1999) for

relatives and related constructions in Spanish.

The debate on the nature of the invariant element che/que can be followed closely by

reading in particular Kayne (1976) and Cinque (1978), Manzini and Savoia (2003) on various

Romance varieties including Italian dialects, and Koopman and Sportiche (2014) on French.

References

Alexandre, N. (2000). A estratégia resumptiva em relativas restritivas no português europeu.

Ph. D. dissertation. Universidade de Lisboa.

Alexiadou, A., Law P., Meinunger A. & Wilder C. (2000). Introduction. In A. Alexiadou, P.

Law, A. Meinunger, & C. Wildern (Eds.) The syntax of relative clauses (pp. 1–51).

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Andrews, A. (2007). Relative clauses. In T. Shopen (Ed.): Language typology and syntactic

description. Vol. 2, Complex constructions (pp. 206–236.) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Auger, J. (1993). On the History of Relative Clauses in French and Some of Its Dialects. In:

H. Andersen (Ed.): Historical Linguistics 1993. Selected Papers from the

11

th

International Conference on Historical Linguistics (pp. 19–32). Amsterdam:

Benjamins.

Battye, A. (1989). Free relatives, pseudo-free relatives, and the syntax of CP in Italian.

Rivista di Linguistica 1: 219−250.

Beltrama, A. & Xiang M. 2016. Unacceptable but comprehensible: the facilitation effect of

resumptive pronouns. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 1: 29. 1–24.

Berruto, G. (1980). La variabilità sociale della lingua. Torino: Loescher.

Berruto, G. (1987). Sociolinguistica dell'italiano contemporaneo. Roma: La Nuova italia

Scientifica.

Browning, M. (1987). Null operator Constructions. Ph. D. dissertation, MIT.

Bianchi, V. (1999). Consequences of Antisymmetry: Headed relative clauses. Berlin:

Mouton de Gruyter.

Bianchi, V. (2000). The raising analysis of relative clauses: A reply to Borsley. Linguistic

Inquiry 31: 123–140.

Bianchi, V. (2002). Headed relative clauses in generative syntax, Part I. Glot International

7-8 : 197–204 and 235–247.

Bîlbîie, G. (2016). The crosslinguistic inconsistency of Comparative Correlatives. In F.

Pratas, S. Pereira & C. Pinto (eds.). Coordination and Subordination: form and meaning.

Selected papers from CSI Lisbon 2014 (pp. 29-58). Cambridge : Cambridge Scholars

Publishing.

Blanche-Benveniste, C. (1990). Usages normatifs et non normatifs dans les relatives en

français, en espagnol et en portugais In J. Bechert, G. Bernini & C. Buridant

(Eds.): Toward a Typology of European Languages (pp. 317–335) Berlin: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Borsley, R. D. (1997). Relative clauses and the theory of phrase structure. Linguistic

Inquiry 28: 629–647.

Brasoveanu, A. (2012). Correlatives. Language and Linguistics Compass 6, 1–20.

24

Brito, A. M. & Duarte I. (2003). Orações relativas e construções aparentadas. In: M. Mateus, A: M.

Brito, I. Duarte, I. Hub Faria, S. Frota, G. Matos, F. Oliveira, M. Vigário & A. Villalva

(Eds). Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (pp. 653–694). Lisbon: Caminho.

Brucart J. M. (1992). Some asymmetries in the functioning of relative pronouns in Spanish.

Catalan Working Papers in Linguistics (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) 113-143

Burzio, L. (1986). Italian Syntax. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Caponigro, I. (2003). Free not to ask: On the semantics of Free Relatives and wh-words

cross-linguistically. Ph.D. dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles.

Caponigro, I. & Fălăuş A. M. (2017). Free Choice Free Relatives in Italian and Romanian.

Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36: 323-363.

Cardinaletti, A. & Guasti, M.T. (2003). Relative clause formation in Romance childs

production. Probus 15, 47-89.

Carlson, G. (1977). Amount relatives. Language 53: 520-542.

Contreras, H. (1999). Relaciones entre las construcciones interrogativas, exclamativas y

relativas. In V. Demonte & I. Bosque (Eds.) Gramática descriptiva de la lengua

española, Vol. 2, (pp. 1931-1964) Madrid: Real Academia Española.

Casalicchio, J. (2013). Pseudorelative, gerundi e infiniti nelle varietà romanze. Affinità

(solo) superficiali e corrispondenze strutturali. Munich: Lincom.

Cecchetto, C. & Donati C. (2015). (Re)labeling, Linguistic Inquiry Monograph 70,

Cambridge: MA, MIT Press.

Cerrón Palomiño, R. (2015). Resumption or contrast? Non-standard subject pronouns in

Spanish Relative Clauses. Spanish in Context, 12: 349-372.

Cinque, G. (1978). La sintassi dei pronomi relativi 'cui' e 'quale' nell'italiano moderno.

Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 3: 31-126.

Cinque, G. (1995). The pseudo-relative and ACC-ing constructions after verbs of

perception. In: Italian syntax and Universal Grammar (pp. 244–275). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Cinque, G. (2013). Typological studies. Word order and relative clauses. London:

Routledge.

Cinque, G. In preparation. Relative clauses. A unified analysis.

Citko, B. (2004). On headed, headless, and light-headed relatives. Natural Language &

Linguistic Theory, 22: 95-126.

Damourette, J. & Pichon, É. (1911-1930). Essai de grammaire de la langue française. Paris:

D'Artrey.

Demirdache, H. (1991). Resumptive chains in restrictive relatives, appositives, and

dislocation structures. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dobrovie Sorin, C. (1994). The Syntax of Romanian. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Donati, C. (1995). Il que relativo spagnolo. Lingua e Stile, 23, 565-595.

Donati, C. (2006). On wh-movement. In L. Lai-Sehn Cheng & N. Cover (Eds.), Wh-

Movement: Moving On (pp. 21–46). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Donati, C. & Cecchetto C. (2011). Relabeling heads: a unified account of relativization

structures. Linguistic Inquiry 42: 519−560.

Gadet, F. (1989). Le français ordinaire. Paris: Armand Colin.

Godard, D. (1989). Français standard et non-standard: les relatives. LINX20, 51–88.

Grillo, N. & Costa J. (2014). A novel argument for the universality of parsing principles.

Cognition 133, 156-187.

Grolla, E. (2005). Resumptive pronouns as last resort: Implications for language acquisition.

Penn Working Papers in Linguistics. Volume /I.I.

Grosu, A. (1994). Three Studies in Locality and Case. London: Routledge.

Grosu, A. (2002). Strange relatives at the interface of two millennia. Glot International 6:

25

145–167.

Grosu, A. (2003). A unified theory of standard and transparent free relatives. Natural

Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 247–331.

Grosu, A. (2004). The syntax-semantics of modal existential wh-constructions. In O.

Mišeska Tomić (Ed.) Balkan syntax and semantics (pp. 405‒438). Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Guasti, M.T. (1988). La pseudorelative et les phenomenes d‘accord. Rivista di Grammatica

Generativa, 13: 35-57.

Hirschbühler, P. & M. L. Rivero (1981). Catalan restrictive relatives - core and periphery.

Language 57, 591-625.

Hirschbiihler, P. & Rivero M.L. (1982). Aspects of the Evolution of Relatives in Romance.

In A. Ahlqvist (Ed.) Papers from the 5

th

International Conference on Historical

Linguistics (132–152) Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hirschbiihler, P. & Rivero M.L. (1983). Remarks on free relatives and matching

phenomena. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 505-520.

Iatridou, S, Anagnostopoulou E., & Izvorski R. (2001). Observations about the form and

meaning of the perfect. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.): Ken Hale: A Life in Language (132–

152) MA, MIT Press.

Kato, M. & Nunes J. (1998). Two sources for relative clause formation in Brazilian

Portuguese. Paper presented at the Eighth Colloquium on Generative Grammar.

Universidade de Lisboa.

Kato, M. & Nunes J. (2009). A uniform raising analysis for standard and nonstandard

relative clauses in Brazilian Portuguese. In J. Nunes (Ed.), Minimalist essays on Brazilian

Portuguese. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kayne, R. (1976). French relative “que”. In: F. Hensey & M. Luján (Eds.) Current studies in

Romance linguistics (255-299) Washington D.C: Georgetown University Press.

Kayne, R. (1994). The Antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kayne, R. (2010) Why isn’t This a complementizer? In: Kayne R. (Ed.). Comparison and

contrasts (pg. 190–227). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koopman, H. & Sportiche D. (2014). The que/qui Alternation: New Analytical Directions.

In P. Svenonius (Ed.) Functional Structure from Top to Toe (46-96). Oxford University

Press, New York.

Lipták, A. (2009). Correllatives crosslinguistically. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Manzini, M.R. & Savoia L. (2003). The nature of complementizers. Rivista di Grammatica

Generativa 28: 87–110.

Matos, G. & Brito A. (2008). Comparative clauses and cross linguistic variation: a syntactic

approach. In O. Bonami & P. Cabredo Hofherr (Eds.) Empirical Issues in Syntax and

Semantics 7 (307–329). http://www.cssp.cnrs.fr/eiss7

Mioto, C. & Lobo M. (2016). Wh-movement. Interrogatives, Relatives and Clefts. In W.L.

Wetzels, J. Costa & S. Menuzzi (Eds.) The Handbook of Portuguese Linguistics (275-

293) Hoboken: NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mulas, M. (2001). The acquisition of relative clauses. An experimental investigation. Tesi di

Laurea. University of Venice.

Poletto, C. & Sanfelici, E. (2019). On relative complementizers and relative pronouns. In: J.

Garzonio & S. Rossi (Eds.), Variation in C: Comparative approaches to the

Complementizer Phrase (pp. 265–298). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Quer J. (1999). Free relatives and the contribution of mood shift to interpretation. In A. Z.

Wyner (Ed.) Proceedings of the 14th Meeting of the Israeli Association for Theoretical

Linguistics (69–89). Ben Gurion University, Beer-Sheva, Israel.

26

Radford, A. (1975). Pseudo-relatives and the unity of subject-raising. Archivum

Linguisticum, 6, 32–64.

Raposo, E. (1989). Prepositional Infinitival Constructions in European Portuguese. In O.

Jaeggli & K.J. Safir (Eds.) The Null Subject Parameter (277-305) Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Riemsdijk, H. van (2006). Free Relatives. In M. Everaert & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.) The

Blackwell Companion to Syntax Vol. II (338-382). Oxford: Blackwell.

Rinke, E. & Assmann E. (2017). The Syntax of Relative Clauses in European Portuguese.

Extending the Determiner Hypothesis of Relativizers to Relative que. Journal of

Portuguese Linguistics, 16: 4, 1–26.

Rivero, M.L. (1980). That-Relatives and Deletion in COMP in Spanish. Cahiers

Linguistiques d’Ottawa 9, 383-399.

Rivero, M.L. (1982). Las relativas restrictivas con que. Nueva Revista de Filología

Hispánica 31, 195-234.

Rivero, M.L. (1984). Diachronic Syntax and Learnability: Free Relatives in Thirteenth-

Century Spanish. Journal of Linguistics, 20, 81-129.

Rizzi, L. (1990). Relativized Minimality. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Rizzi L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In L. Haegeman (Ed.) Elements of

grammar (pp. 281-337). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rizzi, L. & Shlonsky U. (2007). Strategies of subject extraction. In U. Sauerland & H.M.

Gartner (Eds.), Interfaces + Recursion = Language? Chomsky’s Minimalism and the

View from Syntax-Semantics (pp. 115–160). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Rooryck, J. (2000). Configurations of sentential complementation: perspectives from

Romance languages. London: Routledge.

Rouveret, A. (2011). Resumptive pronouns at the interfaces. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sauerland, U. (2000). Two Structures for English Restrictive Relative Clauses. In M. Saito

(Ed). Proceedings of the Nanzan GLOW (pp. 351-366). Nanzan University.

Sauerland, U. (2002). Unpronounced Heads in Relative clauses. In K. Schwabe & S.Winkler

(Eds). The Interfaces: Deriving and Interpreting Omitted Structures (pp. 205-226).

Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Šimík, R. (2011). Modal existential wh-constructions. Ph. D. dissertation. Rijksuniversiteit

Groningen.

Šimík, R. (to apper). Free relatives. In D. Gutzmann, L. Matthewson, C. Meier, H.

Rullmann, and T. E. Zimmermann (Eds.) The Semantics Companion Hoboken, NJ:

Wiley-Blackwell.

Sportiche, D. (2011). French relative qui. Linguistic Inquiry 42.1: 83–124.

Srivastav, V. (1991). The syntax and semantics of correlatives. Natural Language and

Linguistic Theory 9, 637–686.

Stark, E. (1989). Romance restrictive relative clauses between macrovariation and universal

structure. Philologie in Netz 47, 1-15.

Stark, E. (2016). Relative clauses. In A. Ledgeway & M. Maiden (Eds.) The Oxford Guide

to the Romance Languages (pp. 1029-1040). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Staub, A., C. Donati, F. Foppolo & C. Cecchetto (2017). Relative Clause avoidance:

evidence for a structural parsing principle. Journal of Memory and Language, 98, 26 - 44.

Suñer, M. (1998). Resumptive Restrictive Relatives: A Crosslinguistic Perspective.

Language 74, 335–364.

Taraldsen, K. T. (2001). Subject extraction, the distribution of expletives and stylistic

inversion. In A. Hulk & J.-Y. Pollock (Eds.). Subject inversion in Romance and the

theory of universal grammar (pp. 163-182). New York: Oxford University Press.

Veloso, R. (2013). Subordinação relativa. In E. Paiva Raposo, M. F. Bacelar do

Nascimento, M. A. Coelho da Mota, L. Segura, & A. Mendes (Eds.), Gramáticado

27

Português (pp. 2061–2136). Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Vergnaud, J. R. (1974) French Relative Clauses. Ph.D. Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, Mass.

Vernice M., Cecchetto C., Donati C., Moscati V. (2016). Relative clauses are not adjuncts:

an experimental investigation of a corollary of the raising analysis. Linguistische Berichte

246, 139-169.

Vicente, L. (2004). Inversion, reconstruction, and the structure of relative clauses. In J.

Auger, J. Clancy & B. Vance (Eds.) Contemporary approaches to Romance linguistics

(pp. 316–335). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Vries, M. de (2002). The Syntax of Relativization. Utrecht: LOT.

Zribi-Hertz, A. (1984). Préposition orphelines et pronoms nuls. Recherches Linguistiques

12, 46–91.

Notes

i

When not otherwise specified, the examples in Italian and French discussed in the article are made up by the

authors. The data from other Romance languages are either taken from the literature (and hence specified) or

result from discussions with the following colleagues, whom we thank: Josep Quer (Catalan), Carmen Dobrovie

Sorin (Romanian), Carla Soares-Jésel (Portuguese).

ii

In the literature there is no satisfactory explanation of the factors that determine when the article is obligatory

and when it can be omitted. As a matter of fact, there is not even a generalization that captures all the relevant

facts (although there have been several proposals). See Brucart (1992) for some interesting comments.

iii

However, in Spanish there are non-finite structures which closely resemble relatives with que:

(i) Tengo algo que comer .

Have1SG something que to=eat

iv

Various Romance varieties of the Italian area display complementizers showing phi-features agreement. See

Poletto and Sanfelici (2019) and Manzini and Savoia (2003) for data and discussion.

v

On this so-called que-qui rule see Kayne (1976), and Sportiche (2011) and Koopman and Sportiche (2014) for

a recent overview. As for the exact nature of this allomorphy, the most influential analyses argue that qui is an

inflected (agreeing) form of que (Rizzi 1990) or a contracted form que + i(l) = qui : see Rooryck (2000),

Taraldsen (2001), Rizzi and Shlonsky (2007).

vi