January 2018

Deferred Care

How Tax Refunds Enable

Healthcare Spending

About the Institute

The global economy has never been more complex, more interconnected, or faster moving. Yet economists,

businesses, nonprofit leaders, and policymakers have lacked access to real-time data and the analytic tools to

provide a comprehensive perspective. The results—made painfully clear by the Global Financial Crisis and its

aftermath—have been unrealized potential, inequitable growth, and preventable market failures.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute is harnessing the scale and scope of one of the world’s leading firms to explain the

global economy as it truly exists. Its mission is to help decision-makers—policymakers, businesses, and nonprofit

leaders—appreciate the scale, granularity, diversity, and interconnectedness of the global economic system and use

better facts, timely data, and thoughtful analysis to make smarter decisions to advance global prosperity. Drawing

on JPMorgan Chase’s unique proprietary data, expertise, and market access, the Institute develops analyses and

insights on the inner workings of the global economy, frames critical problems, and convenes stakeholders and

leading thinkers.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute is a global think tank dedicated to delivering data-rich analyses and expert insights

for the public good.

Acknowledgments

We thank our fantastic research team, specifically Kerry Zhang, Chenxi Yu, Peter Ganong, and Pascal Noel. This eort would not have

been possible without the critical support of the JPMorgan Chase Intelligent Solutions team of data experts, including Gaby Marano,

Stella Ng, Jacqueline Cush, and Bill Bowlsbey, and the JPMorgan Chase Institute team members Natalie Holmes, Sruthi Rao, Alyssa

Flaschner, Kelly Benoit, Caitlin Legacki, Courtney Hacker, Jolie Spiegelman, and Gena Stern.

We also would like to acknowledge with gratitude the invaluable input of academic experts who provided thoughtful comments,

including Jonathan Parker. For their generosity of time, insight, and support, we are deeply grateful.

Finally we would like to acknowledge Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., for his vision and leadership in establishing the

Institute and enabling the ongoing research agenda. Along with support from across the Firm—notably from Peter Scher, Len Laufer,

Max Neukirchen, Joyce Chang, Steve Cutler, Patrik Ringstroem, and Judy Miller—the Institute has had the resources and support to

pioneer a new approach to contribute to global economic analysis and insight.

Contact

For more information about the JPMorgan Chase Institute or this report, please see our website www.jpmorganchaseinstitute.com

or e-mail institute@jpmchase.com.

2

Executive Summary

Healthcare represents a large and growing fraction of the US economy. Many policy strategies to control the rising cost of healthcare

have involved giving consumers more “skin in the game.” The reasoning behind many of these strategies is that if consumers’ choices

had a more direct impact on their own out-of-pocket spending, they would have more incentive to seek value for money, which in turn

would reduce costs for everyone. But what if consumers’ cash flow constraints prevent them from taking on higher out-of-pocket

costs in the short run, even when doing so would be better in the long run both for them and for the healthcare system overall?

The JPMorgan Chase Institute draws on its Healthcare Out-of-Pocket Spending Panel (HOSP) to investigate how a specific and

important cash infusion—a tax refund payment—drives the timing of out-of-pocket expenditures on healthcare. Consumers’ spending

on healthcare was significantly aected by cash flow dynamics. Even though they could likely anticipate the amount of the cash

infusion that their refund payment would bring, they did not increase their spending until the refund arrived; then, as soon as it

arrived, they immediately increased their spending.

Our analysis uncovers five key findings:

1. Consumers immediately increased their total out-

of-pocket healthcare spending by 60 percent in

the week after receiving a tax refund. Spending

remained elevated for about 75 days, during which

consumers spent 20 percent more out of pocket

on healthcare than before the tax refund.

2. In the week after the tax refund, out-of-pocket

healthcare spending on debit cards increased by 83

percent, and electronic payments increased by 56

percent. There was no change in credit card spending.

This suggests that liquidity from the tax refund

enabled the increase in healthcare spending.

3. In-person payments to healthcare service providers

represented 62 percent of tax refund-triggered additional

healthcare spending. This indicates that the timing

of a cash infusion aected when consumers received

healthcare, not just when they made a healthcare payment.

4. The tax refund caused consumers to make visits to

dentists’ and doctors’ oces and pay outstanding

hospital bills which they had deferred.

5. Cash flow dynamics had less eect on the out-of-

pocket healthcare spending patterns of consumers

who had higher balances in their checking account or

who had a credit card prior to the refund payment.

We conclude that cash flow dynamics are a significant driver of out-of-pocket healthcare spending. Even when consumers knew

with near-certainty the size and source of a major cash infusion, they still waited until the infusion arrived before spending. These

dynamics may shed light on ways insurers, healthcare providers, employers, and financial service providers could help consumers

receive care when they need it rather than when they have cash on hand to pay for it.

3

Introduction

Healthcare represents a large and growing fraction of the US

economy. Many policy strategies to control the rising cost of

healthcare have involved giving consumers more “skin in the

game.” The reasoning behind many of these strategies is that

if consumers’ choices had a more direct impact on their own

out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure, they would have more

incentive to seek value for money, which in turn would reduce

costs for everyone (Handel, 2013; Bhargava, Loewenstein,

Sydnor, 2017). But what if consumers’ cash flow constraints

prevent them from taking on higher out-of-pocket costs in the

short run, even when doing so would be better in the long run

for them and for the healthcare system overall?

In this study, we use a specific and important type of cash

infusion—a tax refund payment—to show that consumers’

spending on healthcare is significantly aected by cash flow

dynamics. Tax refunds are a significant cash flow event for

many households. In 2016, 73 percent of tax filers received a

tax refund, with an average refund of $2,860 (Internal Revenue

Service, 2017a).

1

When family members received this significant

cash infusion, they immediately increased their out-of-pocket

spending on healthcare. Furthermore, even though they likely

were able to anticipate the amount of the cash infusion as

soon as they had filed their returns, they did not increase their

spending until the refund actually arrived.

We draw on the JPMC Institute Healthcare Out-of-pocket

Spending Panel (JPMCI HOSP) data asset and examine how

healthcare payments vary in the days and weeks around

when account holders receive their tax refunds.

2

We analyze

average out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure on over a dozen

categories of healthcare goods and services for each day in the

100 days before and after a tax refund payment, for 1.2 million

checking account holders in the JMPCI HOSP who received a tax

refund between 2014 and 2016. This represents the first ever

daily event study documenting how families’ out-of-pocket

healthcare spending responds to the arrival of this significant

cash infusion.

3

Our analysis uncovers five key findings:

1. Consumers immediately increased their total out-of-pocket

healthcare spending by 60 percent in the week after receiving

a tax refund. Spending remained elevated for about 75 days,

during which consumers spent 20 percent more out of pocket

on healthcare than before the tax refund.

2. In the week after the tax refund, out-of-pocket healthcare

spending on debit cards increased by 83 percent, and

electronic payments increased by 56 percent. There was no

change to credit card spending. This suggests that liquidity

from the tax refund enabled the increase in healthcare

spending.

3. In-person payments to healthcare service providers

represented 62 percent of tax refund-triggered additional

healthcare spending. This indicates that the timing of a cash

infusion aected when consumers received healthcare, not

just when they made a healthcare payment.

4. The tax refund caused consumers to make visits to dentists’

and doctors’ oces and pay outstanding hospital bills which

they had deferred.

5. Cash flow dynamics had less eect on the out-of-pocket

healthcare spending patterns of consumers who had higher

balances in their checking account or who had a credit card.

Out-of-pocket healthcare spending

and ability to pay: Previous findings

and remaining questions

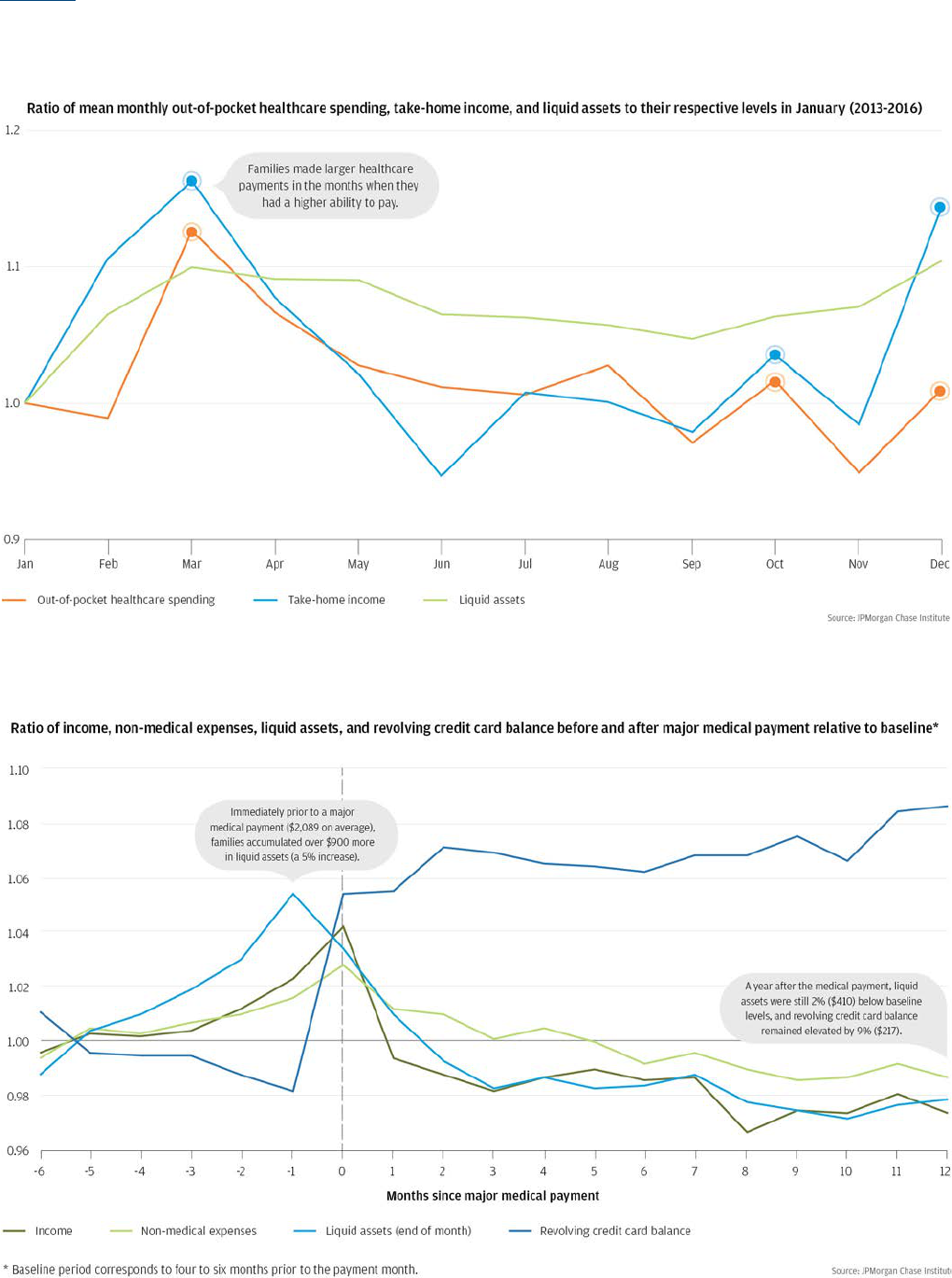

In previous research, the JPMorgan Chase Institute has shown

that account holders spend more out of pocket on healthcare

when they have more money. This is true even within a

single year. As shown in Figure 1, the average account holder

consistently spends more out of pocket on healthcare in

March and December; these two months are also consistently

marked by higher than average income (Farrell and Greig,

2017a). Furthermore as Figure 2 illustrates, account holders

timed major medical payments to occur in the same month as

increases in income and shortly after increases in liquid assets

(Farrell and Greig, 2017b).

4

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Introduction

Figure 1: Out-of-pocket healthcare payments and take-home income peak in March.

Figure 2: Account holders time major medical payments to coincide with higher income and bank balances.

5

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Introduction

The patterns in Figures 1 and 2 are striking because they suggest that cash flow dynamics may drive when families receive healthcare.

Still, important questions remain unanswered:

1. If family members are able to anticipate a cash infusion with near certainty, do they still wait for that infusion to arrive before

attending to their spending needs?

2. Do major healthcare payments follow increases in liquid assets because families time inflows to their needs, as opposed to

delaying spending until inflows arrive?

3. The months when income and out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure both tend to be highest (March and December) also happen

to fall during peak infectious disease season.

4

Could it be that people just need more healthcare at these times?

4. Even if cash flow dynamics aect when consumers pay for care, what does that mean for when they receive it? For example,

consumers might seek care when they need it, but then carry balances with healthcare providers until they have the cash to pay

down those balances. They might take advantage of volume discounts to stockpile medications and other supplies when income

is high, and then consume those stockpiles gradually as their needs dictate. In these cases, cash flow dynamics would drive when

consumers spend out of pocket on healthcare goods and services, but not when they get the benefits of those goods and services.

In this study, we address questions one through three directly, by observing out-of-pocket expenditures on healthcare in the days

around receipt of a significant cash infusion: a tax refund payment (Box 1). Account holders can anticipate the amount of their tax refund

payment almost perfectly once they file their returns, but they can neither control nor anticipate the precise timing of that payment.

Therefore, when we observe that increases in healthcare spending follow closely after receipt of the tax refund, we know that it is

implausible that families could have first planned the timing of the spending, and then timed the tax refund to immediately precede it.

We also know that it is implausible that family members coincidentally fall ill just as a tax refund payment arrives. As shown in Figure

3, the actual calendar date when a refund is received varies widely. Even the modal day in 2016 (February 10), accounted for only 3.8

percent of tax refund payments for that year. For dierent account holders, the 100 days before and after the tax refund payment

correspond to dierent points in the calendar, so there is no systematic relationship between days before or after the payment and

seasonal dynamics like infectious disease risk.

Figure 3. The timing of tax refund payments varies widely.

In order to address the fourth question, we separately analyze out-of-pocket healthcare payments to goods providers (for

example, drug stores or medical supply merchants) and to service providers (for example, doctors’ oces, dentists’ oces, or

hospitals). We further disaggregate payments to service providers that are made in person versus those that are made remotely,

based on administrative data that indicate whether a debit or credit card was physically present at the time of payment. Payments

6

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Introduction

made at the point of service are likely made at the time of service as well. Therefore, we infer in-person payments to healthcare

providers to represent services that were not received until the tax refund arrived. We characterize these payments as covering

costs of deferred care. In contrast, healthcare payments made remotely are likely to reflect payments made for services received

in the past and for which consumers were carrying unpaid balances. We describe the increase in remote payments after the tax

refund as deferred bill payments.

Box 1: Tax refunds are more than a convenient case study

Focusing on cash infusions that come specifically through tax refunds allows us to directly address important unanswered

questions. But tax refunds are not just a convenient case study. In previous research (Figure 1), we observed that out-of-

pocket healthcare expenditures were highest during tax refund season, which suggests that these payments may in fact

be a primary driver of expenditure on healthcare. Roughly three-fourths of tax filers receive a tax refund (IRS, 2017). The

average total tax refund in our sample was $3,100, which is 2.6 times the average payroll deposit.

5

This is a significant

amount of money to receive in a concentrated period of time. In 70 percent of cases, account holders received their entire

total tax refund on the same day. In 90 percent of cases, the entire amount arrived in multiple payments over the span of

a week or less. For 40 percent of account holders, a tax refund payment represents the largest single cash infusion into

their accounts for the whole year. Account balances are consistently highest on the day that the first tax refund payment is

deposited, as shown in Figure 4. For those whose capacity to spend out of pocket on healthcare is constrained by cash flow

dynamics, tax refund season is likely to be the time when those constraints are most alleviated.

Figure 4. Checking account balances in JPMCI HOSP increased by more than 50 percent when the first tax refund

payment was received.

Back to Contents

7

Findings

Finding

One

Consumers immediately increased their out-of-pocket healthcare spending

by 60 percent in the week after receiving a tax refund. Spending remained

elevated for about 75 days, during which consumers spent 20 percent more out

of pocket on healthcare than before the tax refund.

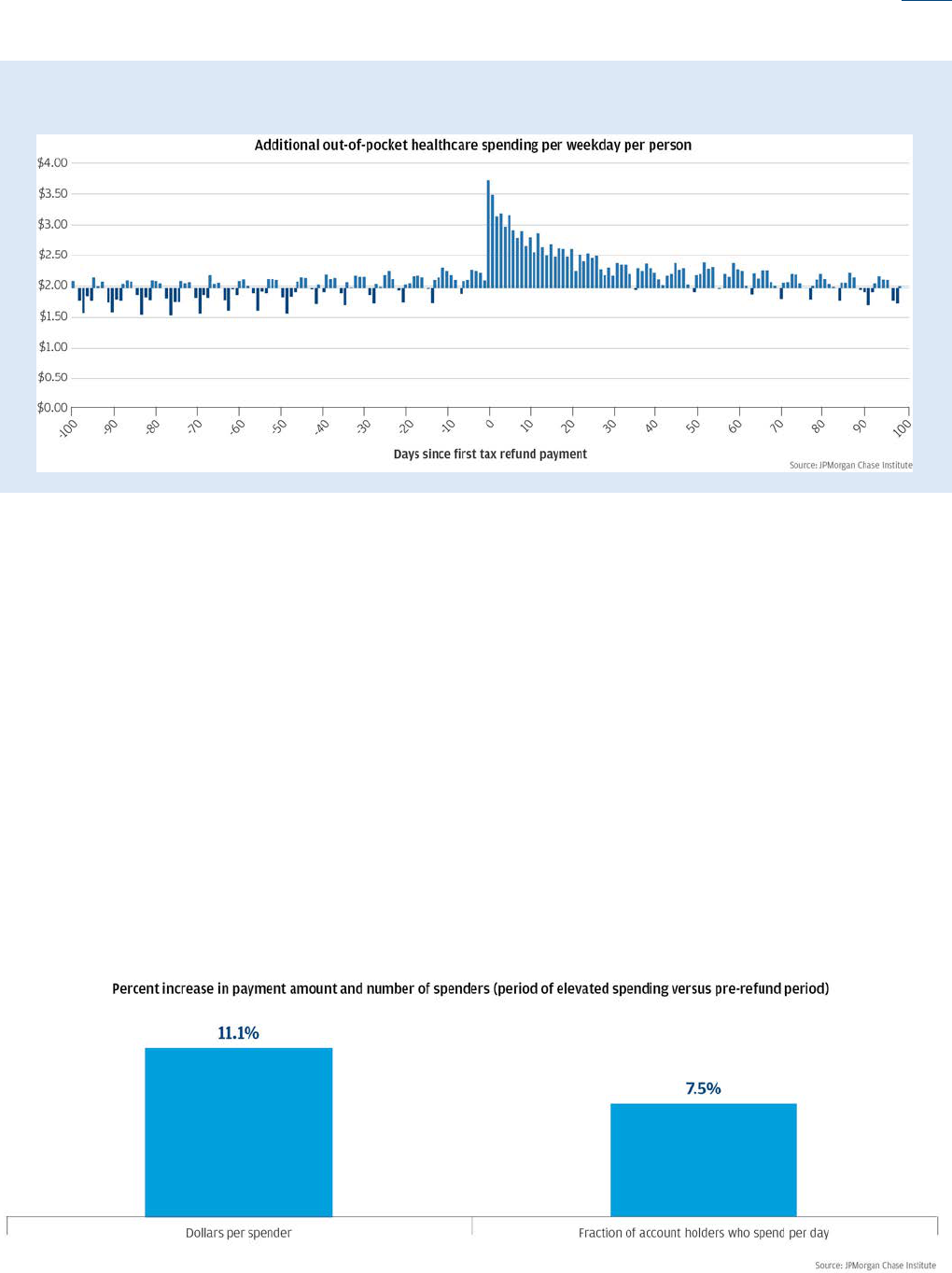

Figure 5 shows out-of-pocket healthcare spending in the JPMCI HOSP data asset in the 100

days before and after account holders received their first 2016 tax refund. The sharp

rise in the line on “day 0” indicates that spending increased immediately when the

refund payment arrived. Total healthcare spending was 60 percent higher in the

week after the refund payment, compared with a typical week prior to the refund.

This represents a significant departure from the stable pattern of spending over

the 100 days prior to the payment. The response to the cash infusion tailed o

after about 75 days, when spending returned to its pre-infusion pace. Over the

entire period of elevated spending, out-of-pocket healthcare spending was about

20 percent higher than a comparable period prior to the refund payment.

The arrival of the tax

refund triggered 75 days

of elevated out-of-pocket

spending on healthcare.

Figure 5. Consumers immediately increased their out-of-pocket healthcare

spending by 60 percent in the first week and 20 percent in the 75 days after

receiving a tax refund payment.

8

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

The total additional spending represented in the shaded area of Figure 5 comes to about $30 per account in JPMCI HOSP. We infer

that this healthcare spending would have occurred at a dierent time if the tax refund payment had arrived at a dierent time

(see Box 2). Reflecting this inference, we will refer to these dollars as tax refund-triggered additional healthcare spending.

It is important to note that some of the tax refund-triggered additional spending is almost certainly for things that can wait. For example,

if a routine check-up occurs in March instead of January because a tax refund arrives in March instead of January, this may not be any

special cause for concern. In highlighting the fraction of spending for which the timing is determined by the arrival of cash, rather than

by customers’ needs or convenience, we are careful not to imply that every one of those dollars must necessarily be cause for concern.

Box 2: Computing tax refund-triggered additional healthcare spending

One way to quantify the impact of cash flow dynamics on out-of-pocket healthcare spending is with the following thought

experiment: “How much more did account holders spend on healthcare after the first tax refund payment arrived, compared

with what they would have spent on healthcare if their per weekday pace had carried on as it was prior to the refund payment?”

We identify the additional spending based on changes in the average per weekday pace of healthcare spending (rather than

average per day), because healthcare spending is naturally elevated on weekdays relative to weekends. Therefore, spending

will appear higher on “day 0” than the days around it, simply because tax refund payments always arrive on a weekday. We

sweep out this eect by adjusting each of the days to account for the fraction of account holders for whom that day falls on a

weekend.

6

Actual spending per person per day and our adjusted series based on the per person per weekday rate are shown

together in Figure 6. We use the adjusted series (in blue) to compute “tax refund-triggered additional spending.”

Figure 6. We adjust for weekend and weekday dynamics in computing “tax refund-triggered additional spending.”

Our computation of “tax refund-triggered additional spending” is represented graphically in Figure 7, which is a recasting of

the adjusted series (blue) in Figure 6. During any period, we can add up the heights of all the positive deviations (lighter bars),

and subtract the heights of all the negative deviations (darker bars), to arrive at a total number of “additional dollars” spent.

Over the period from day -100 to day -1, the cumulative additional spending comes to exactly $0 (by construction). Beginning

at day 0, cumulative additional spending increases until about day 75, when it stabilizes around $30.

Subject to the assumption that the jump in spending would have occurred on whatever day the tax refund arrived, the

additional spending can be described as “triggered” by the tax refund. This assumption is plausible given the extent to which

day 0 diers from all of the 100 days before it. The sense in which this spending is “triggered” by the refund refers specifically

to its timing; it does not refer to the economic concept of a marginal propensity to consume.

9

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

Figure 7. “Additional healthcare spending” in each of the 100 days before and after the first tax refund payment

As shown in Figure 5, out-of-pocket healthcare spending remained elevated for roughly 75 days after the first tax refund payment was

received. Average spending per account was about 20 percent higher during this period than over a comparable period before the first

refund payment. This increase is driven by two dynamics—larger healthcare payments in a typical day, and more account holders making

healthcare payments in a typical day. The more powerful factor is the former, accounting for 59 percent of the tax refund triggered

additional healthcare spending.

7

As shown in Figure 8, the typical spender spent 11.1 percent more in a typical day during the period

of elevated spending, compared with the pre-refund period ($94 per day during the period of elevated spending, and $85 during the

pre-refund period). The other 41 percent of the increase is accounted for by the fact that the number of spenders on a typical day rises

from 2.3 percent of account holders during the pre-refund period to 2.5 percent during the period of elevated spending—translating to

a 7.5 percent rise (right bar in Figure 8).

We also observe that this increase in the average payment was driven in large part by an increase in the largest payment amounts

(account holders spending $150 or more in a single day). The cash infusion represented by a tax refund payment allowed more people

to make more purchases of healthcare goods and services, but, even more consequentially, it facilitated larger payments. This implies

that the cash infusion generated by a tax refund payment triggered additional spending on large healthcare ticket items that consumers

could have least aorded out of their pre-refund cash flow.

Figure 8. The number of consumers spending out-of-pocket on healthcare increased on a typical day after a tax refund was

received, and the average payment increased substantially.

10

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

Finding

Two

In the week after the tax refund, out-of-pocket healthcare spending on debit cards

increased by 83 percent, and electronic payments increased by 56 percent. There

was no change to credit card spending. This suggests that liquidity from the tax

refund enabled the increase in healthcare spending.

Figure 9 disaggregates total out-of-pocket healthcare spending by payment instrument in the 100 days before and after account

holders receive their first tax refund payment. In the week following the arrival of the payment, out-of-pocket healthcare payments

on debit cards increased the most, by 83 percent. Spending via electronic payments also increased by 56 percent, but from a much

smaller base. By contrast, spending on credit cards did not change in response to the tax refund. Also striking is the degree to which

these patterns persist year after year (Figure 14 in the Appendix). In each of the three observed years, healthcare spending on

credit cards showed no change around the time of the tax refund, while debit card spending and electronic payments rose sharply.

The sharp rise in out-of-pocket healthcare spending on debit cards and electronic payments indicate that consumers had unmet

healthcare needs or unpaid healthcare bills, to which they waited to attend until after the cash arrived. Moreover the spending

response for healthcare is greater, in aggregate, than other types of spending: non-health spending on debit cards increased by 54

percent in the week after the tax refund (compared to 83 percent for health spending on debit cards).

The fact that the arrival of the tax refund triggers additional healthcare spending is striking because as soon as families file their tax

returns, they can anticipate with near certainty how much of a cash infusion to expect. If they had access to formal or informal credit

or to a cash buer, they could begin spending as soon as they learned the exact amount to expect. For example, one might expect

credit card spending to rise in anticipation of the refund payment. However, out-of-pocket healthcare spending on credit cards did

not increase either before or after the tax refund. For account holders who did not already know the amount of refund to expect,

the tax filing provided new information but no new liquidity; we see no evidence that this impacted spending behavior. Since filers

knew their tax refund amount when they filed, the refund payment itself provided new liquidity but no new information. The fact

that spending jumped in response to the refund payment, therefore, suggests that consumers were waiting for cash before making

healthcare payments, not just information about how much to expect.

Figure 9. Spending on debit cards increased 83 percent in the week after receiving a tax refund, with no osetting change

to credit card spending.

11

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

Finding

Three

In-person payments to healthcare service providers represented 62

percent of tax refund-triggered additional healthcare spending. This

indicates that the timing of a cash infusion aected when consumers

received healthcare, not just when they made a healthcare payment.

Figure 10 disaggregates total out-of-pocket healthcare spending by payments made in person at healthcare service providers,

payments made remotely to healthcare service providers, and payments in any form (in-person or remote) to goods providers, in

the 100 days before and 100 days after account holders received their first tax refund payment.

8

Payments in person at service providers were 54 percent higher during the seven days after account holders received their first tax

refund payment than a typical week prior to the refund. Remote payments to service providers were elevated by 79 percent, but o

of a smaller base and for a shorter period of time than in-person payments. Payments to providers of stockable healthcare goods

increased by only 22 percent.

Figure 10. In the week of receiving a tax refund, in-person payments for healthcare service increased by 54 percent, and

remote payment of healthcare bills increased 79 percent.

12

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

It is likely that payments made at the point of service are also made at the time

that the service is provided. This inference is supported by the sharper rise and

faster decay in remote payments in Figure 10. This likely reflects the fact that

consumers have more control over when they can make remote payments,

whereas in-person payments may require appointments to be made and

kept. Based on this inference, we conclude that the additional dollars spent

in person in Figure 10 go toward deferred care—healthcare services that

consumers would have received earlier, if their refund payment had come

earlier. In contrast, payments made remotely are likely to reflect payments

made for services that consumers had received in the past and for which they

were carrying balances (deferred bill payments).

The additional

spending triggered

by the tax refund went

disproportionately towards

in-person healthcare services

that that were likely deferred

from the period before

the refund arrived.

Figure 11 compares the distribution of the tax refund-triggered additional

spending to the distribution of total spending prior to the tax refund. We observe

that 62 percent of tax refund-triggered additional dollars were paid in person at

service providers (deferred care), a larger share than in the 100 days prior to the tax

refund (57 percent). Thirty-seven percent of tax refund-triggered additional healthcare

spending was paid remotely to service providers (deferred bill payments), compared to 33

percent before the tax refund.

Only 1 percent of tax refund triggered additional healthcare spending was paid to providers of healthcare goods

that can be stockpiled, like drugs or medical supplies, compared to 10 percent before the tax refund.

Figure 11: Most of the tax-refund triggered additional healthcare spending paid for deferred care.

Most consumers did not appear to use their tax refund to stock up on drug supplies and other healthcare goods. Rather, the additional

spending went disproportionately toward in-person healthcare services which were likely deferred from the period before the refund

arrived. We next explore what kinds of healthcare services were most likely to have been deferred.

13

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

Finding

Four

The tax refund caused consumers to make visits to dentist and doctor oces

and pay outstanding hospital bills which they had likely deferred.

Dentists received a disproportionate share of the refund-triggered additional spending. Figure 12 illustrates that 32 percent of the

refund-triggered in-person payments to service providers went to dentists. By contrast, during the period prior to the tax refund

payment only 27 percent of in-person payments to service providers went to dentists (figures not shown). The refund-triggered

additional healthcare spending was less likely to go to doctors or hospitals, which, respectively, received only 23 percent and 6

percent of the additional spending triggered by the refund payment (compared to 27 percent and 7 percent of spending during

the pre-refund period respectively). The remaining 39 percent went towards other healthcare providers, including nursing service

providers, ambulance service providers, medical laboratories, opticians, optometrists, and chiropractors.

Remote payments for healthcare services (bill payments) mostly represented hospital bills even during the period before the tax

refund arrived; however, hospitals still received a disproportionate share of refund-triggered remote payments to service providers

(31 percent, compared with 28 percent during the pre-refund period). Twenty-one percent of refund-triggered additional remote

payments for services went to doctors and 6 percent went to dentists (compared to 19 percent and 15 percent respectively prior to

the tax refund, figures not shown).

In short, the tax refund triggered consumers to make visits to dentist and doctor oces and pay outstanding hospital bills which

they had likely deferred.

Figure 12. Dentist and doctor visits accounted for more than half of the deferred care that would have been received

earlier, if the tax refund payment had come earlier.

14

DEFERRED CARE: HOW TAX REFUNDS ENABLE HEALTHCARE SPENDING

Findings

Finding

Five

Cash flow dynamics had less eect on the out-of-pocket healthcare spending

patterns of consumers who had higher balances in their checking accounts or

who had a credit card before the payment arrived.

If consumers have access to formal or informal credit or a cash buer, they may be able to use

these tools to time spending more to their healthcare needs or to their convenience, rather

than to the arrival of a cash infusion. In Figure 13, we segment account holders on the basis

of their average daily checking account balances over the 100 days prior to their first tax

refund payment, and also on the basis of whether we observe any evidence that they had

a credit card prior to the first tax refund payment.

For consumers

who had less access

to liquidity, the tax

refund triggered a larger

increase in healthcare

spending.

We observe a clear gradient. Among account holders whose average daily checking

account balance was less than $536 (the lowest quintile), healthcare spending was 220

percent higher in the week after receiving the first tax refund payment compared with a

typical week prior to the refund payment. By contrast, for account holders with average

daily balances over $3,577 (the highest balance quintile), healthcare spending increased

by only 11 percent with the cash infusion. In other words, account holders with the lowest

checking account balances increased their out-of-pocket healthcare spending after the tax refund

by 20 times more than those with the highest balances. Similarly, healthcare spending increased more

sharply among those who did not have a credit card than among those who did (104 percent compared with 48 percent, respectively).

9

For consumers who had more spending power prior to the refund, the tax refund triggered a smaller increase in healthcare spending.

Figure 13. The cash infusion from a tax refund payment triggered a significantly sharper increase in healthcare

spending among account holders who had lower checking account balances or who did not have a credit card prior to

receiving their tax refund.

Back to Contents

15

Implications

Cash flow dynamics are a significant driver of out-of-pocket healthcare spending. Even when consumers likely know the size and

source of a major cash infusion, they still wait for the infusion to arrive before spending and begin spending immediately when it

does. Consumers in the JPMCI HOSP increased their out-of-pocket healthcare spending by 60 percent in the week after receiving a

tax refund. This spending would most likely have occurred earlier, if the refund payment had arrived earlier. This evidence on the

power of cash flow dynamics to drive behavior indicates opportunities for insurers, employers, healthcare providers, and financial

service providers to help consumers receive care when they need it, rather than when they have cash on hand to pay for it.

Cash flow dynamics drive when consumers receive healthcare, and not only when they pay for it. More than 60 percent of

tax refund-triggered additional healthcare spending was paid for in person and therefore likely represents care that consumers

would have received sooner, if the tax refund had come sooner. More than half of this care was provided by dentists and doctors.

Almost certainly, the timing of some of these services is not especially sensitive. However, we also observe that consumers who had

more spending power prior to the refund payment were less likely to time their spending based on when their tax refund arrived.

This implies that at least some consumers might otherwise prefer not to have the timing of their services determined by cash flow

considerations. The consequences to physical and financial health of deferring these services should be a target of empirical policy

research.

Health insurers and employers can play a role in helping people smooth their healthcare spending. Giving consumers “skin

in the game” may not be an eective way to control the rise of healthcare costs if consumers delay more cost-eective care (for

example, preventive or diagnostic services) due to short run cash flow constraints, only to require more costly interventions in the

long run. Therefore, strategies to curtail unnecessary healthcare utilization should not give consumers incentive to delay necessary

care because they are waiting for a cash infusion they know is coming. For example, insurers and employers could cooperate to oer

consumers who are enrolled in High Deductible Health Plans (HDHP) with an associated Health Savings Account (HSA) a mechanism

to allocate some of their tax refund directly to their HSA when they file their return, and even to begin spending from that allocation

before the refund payment arrives. Given that over a third of HSAs received no contributions in 2016 (Fronstin, 2017), employers

could more actively encourage and facilitate HSA allocations. For example, employees might be given an option to specify that HSA

allocations are automatically made from their paycheck on a regular basis, with built-in adjustments during periods of predictable

income spikes, like five-Friday months and bonus season.

Consumers’ willingness to enroll in a plan that includes an HSA may not just be driven by longer run considerations like deductibles

and premiums, but also by shorter run factors like whether covered services are paid for up-front or reimbursed later, and when

in the year contributions are made to HSAs. Understanding how consumers approach these tradeos can help inform the design of

innovative approaches to help people make the healthcare decisions that are best for their long run physical and financial health,

and for the sustainability of the system overall.

Patients and healthcare providers should take cash flow considerations explicitly into account when working together to

design an optimal healthcare plan. Our findings highlight the deep complexity that consumers and providers face in being active

partners in healthcare. For many consumers, this is not solely a question of working with their healthcare providers to align their

healthcare choices with their needs and financial resources. It is also a question of planning a care schedule so that out-of-pocket

costs line up with cash flow conditions. What care may be put o until an expected cash infusion arrives? For care that must not be

put o, how can the costs be covered in the meantime? Consumers need to understand both the health and financial consequences of

their choices in a dynamic framework where timing may sometimes be a critical component. Healthcare providers should prioritize

elements of a patient’s healthcare plan and oer clear medical advice around the consequences of delay.

16

Financial service providers have an opportunity to design

innovative products to meet the cash flow needs of consumers

and healthcare providers. Our findings indicate that tax refund

payments trigger consumers to immediately begin making

large healthcare payments which they had been deferring.

This suggests that financial service providers could design

innovative savings, credit, and payment tools (perhaps even

directly integrating these with planning and budgeting tools)

to give their customers more control over when and how to

cover large-ticket expenditures. These tools would likely be

useful even beyond healthcare. In the healthcare industry

specifically, a significant fraction of the tax refund-triggered

additional healthcare spending goes to paying down balances

with healthcare service providers. This indicates an opportunity to

cooperate with financial service providers to increase the amount

of care that can be extended and received when it is needed.

Cash flow dynamics are

a significant driver of out-

of-pocket healthcare spending.

This has important implications

for insurers, employers, healthcare

providers, and financial service

providers, to ensure consumers receive

healthcare when they need it, rather

than just when they have cash

on hand to pay for it.

Back to Contents

18

References

Barrow, Lisa and Leslie McGranahan. 2000. “The Eects of the Earned Income Credit on the Seasonality of Household Expenditures.”

National Tax Journal, Vol. 53, No. 4. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=251094.

Baugh, Brian, Itzhak Ben-David, and Hoonsuk Park. 2014. “Disentangling Financial Constraints, Precautionary Savings, and

Myopia: Household Behavior Surrounding Federal Tax Returns.” NBER Working Paper no. w19783. Available at: https://ssrn.com/

abstract=2374558.

Bhargava, Saurabh, George Loewenstein, and Justin Sydnor. 2017. “Evaluating Health Insurance Decisions: Health Plan Choices from

a Menu With Dominated Options.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Volume 132, Issue 3 (August 2017): 1319–1372. https://dx.doi.

org/10.1093/qje/qjx011.

Broda, Christian, and Jonathan A. Parker. 2014. “The economic stimulus payments of 2008 and the aggregate demand for consumption.”

Journal of Monetary Economics. Volume 68, Supplement: S20-S36, https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx011.

Cilke, James. 2014. “The Case of the Missing Strangers: What we know and don’t know about non-filers” National Tax Association 107th Annual

Conference Proceedings, 2014. Available at: https://www.ntanet.org/conference/2014/11/107th-annual-conference-proceedings-2014/.

Farrell, Diana, and Fiona Greig. “Paying Out-of-Pocket: The Healthcare Spending of 2 Million US Families.” JPMorgan Chase Institute, 2017a.

Farrell, Diana, and Fiona Greig. “Coping with Costs: Big Data on Expense Volatility and Medical Payments.” JPMorgan Chase Institute, 2017b.

Handel, Benjamin R. 2013. “Adverse selection and inertia in health insurance markets: When nudging hurts.” The American Economic

Review 103, no. 7 (2013): 2643-2682. https://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.7.2643

Parker, Jonathan A. 2017. “Why Don't Households Smooth Consumption? Evidence from a $25 Million Experiment.” American Economic

Journal: Macroeconomics. Volume 9, number 4: 153-183. https://dx.doi.org/10.1257/mac.20150331

Fronstin, Paul. “Health Savings Account Balances, Contributions, Distributions, and Other Vital Statistics, 2016: Statistics from the EBRI

HSA Database” Employer Benefits Research Institute Issue Brief No. 438. September 2017. Available at: https://www.ebri.org/pdf/

briefspdf/EBRI_IB_438_HSAs.19Sept17.pdf

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Filing Season Statistics for Week Ending Dec. 30, 2016. Internal Revenue Service, 2017a. Available at

https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/filing-season-statistics-for-the-week-ending-december-30-2016.

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Filing Season Statistics for Week Ending Dec. 25, 2015. Internal Revenue Service, 2017b.

Molinari, Noelle-Angelique M., Ismael R. Ortega-Sanchez, Mark L. Messonnier, William W. Thompson, Pascale M. Wortley, Eric Weintraub,

Carolyn B. Bridges. 2007. “The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: Measuring disease burden and costs.” Vaccine. Volume 25:

(2007): 5086–5096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046

Blanton, Lenee, Noreen Alabi, Desiree Mustaquim, Calli Taylor, Krista Kniss, Natalie Kramer, Alicia Budd, Shikha Garg, Charisse N.

Cummings, Jessie Chung, Brendan Flannery, Alicia M. Fry, Wendy Sessions, Rebecca Garten, Xiyan Xu, Anwar Isa Abd Elal, Larisa

Gubareva, John Barnes, Vivien Dugan, David E. Wentworth, Erin Burns, Jacqueline Katz, Daniel Jernigan, Lynnette Brammer, “Update:

Influenza Activity in the United States During the 2016–17 Season and Composition of the 2017–18 Influenza Vaccine.” MMWR Morbidity

Mortality Weekly Report 2017. Volume 66: 668–676. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6625a3

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Hospital Discharge Survey, 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhds/

about_nhds.htm

New York State Department of Health (NYSDH). Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS), 2016. Available at:

https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/

Back to Contents

19

Endnotes

1 “Tax filers” are not the entire US population. In 2011, for

example, around 10 percent of the population may not have

been represented in any tax filing document, because their

households did not file a return with the IRS. Using other

administrative information, Cilke (2014) finds evidence that

most of the income of these non-filers comes from government

transfers. Nonetheless, for the small minority of the US

population who are non-filers, we do not know if they would

have received refund payments if they had filed, nor how

any such payments would have aected their out-of-pocket

healthcare spending behavior.

2 The JPMCI HOSP data asset was constructed using a sample

of de-identified core Chase customers for whom we observe

financial attributes, including out-of-pocket healthcare spending

between 2013 and 2016. For the purposes of our research, the

unit of analysis was the primary account holder. We focused

on accounts held by adults aged 18 to 64, as adults 65 and

older were more likely to make payments using paper checks,

which we could not categorize. To provide better visibility into

income and spending, we selected accounts which had at least

five checking account outflows each month, at least $5,000 in

take-home income each year, and used paper checks, cash, and

non-Chase credit cards for less than 50 percent of their total

spending. The JPMCI HOSP data asset includes customers who

resided within the 23 states in which JPMorgan Chase has a

retail branch presence. We re-weighted our population to reflect

the joint age and income distribution among the 18-64 year old

population within each state. See Farrell and Greig (2017a) for a

full description of the JPMCI HOSP data asset.

3 Other eorts to estimate the impact of tax refunds on consumer

spending have done so on a monthly basis and documented

higher total spending and specifically durable spending in

February among families eligible for the Earned Income Tax

Credit (Barrow and McGranahan, 2000). A number of studies

have measured the impacts of changes in tax rebates on

household spending with higher frequency. See Parker (2017)

and Broda and Parker (2014) for recent summaries of this

literature and evidence using Nielson Consumer Panel that

weekly household spending increased by 9-10 percent after

receiving the 2008 Economic Stimulus Payment. Notably, Baugh

et al. (2014), based on daily transaction data, provide evidence

that in the week following receipt of their tax refund, households

increase their restaurant spending by 8 percent, retail spending

by 12 percent and, ATM withdrawals by 16 percent.

4 The seasonality of influenza, which is a significant driver of

healthcare costs (Molinari, Ortega-Sanchez, et al., 2007), is

closely tracked by the US Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. In the 2016/2017 season, influenza activity peaked

in late February, and prevalence fell sharply starting in the third

week of March (Blanton, Alabi, et al., 2017). Nationally, inpatient

discharges are consistently highest in March (NCHS, 2010) and

the daily rate of outpatient visits to hospitals in the state of New

York peak in March (NYSDH, 2016).

5 The average value of all tax refunds received in a year in the

JPMCI sample was $3,100; this includes directly deposited

federal and state tax refunds. This is roughly comparable

to national estimates. The average federal tax refund (i.e.,

not including state refunds) was $2,860 ($2,995 for directly

deposited tax refunds) in 2016, $2,797 ($2,957 for directly

deposited tax refunds) in 2015, and $2,792 ($2,918 for directly

deposited tax refunds) (IRS, 2017a; IRS, 2017b).

6 The cyclicality in the unadjusted (green) series in Figure 6 is

driven by the fact that healthcare spending on weekdays is

naturally elevated relative to weekends, and the fact that the IRS

does not distribute tax refund payments on weekends. As a

result, day 0 is a weekday for all 1.2 million accounts in our

sample, which therefore means that days 0+/- 7, 0+/- 14, and so

on also fall on weekdays for 100 percent of the sample. By

contrast, days 4+/-7, 4+/-14, and so on fall on weekends for 48

percent of the sample. Therefore, we compute the weekday-

adjusted (blue) series in Figure 6 as follows, for each day t:

Where x

t

is average out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure per

account on day t, x

p

is “typical” average daily expenditure per

account (where “typical” is identified by the 100 days prior to

the tax refund payment), and r

t

is the ratio of the fraction of

accounts for whom day t is a weekday to the “typical” fraction of

account-days that fall on weekdays (i.e., the 100 days prior to

the tax refund payment). Therefore, if day t is more likely to fall

on a weekday than is typical, then r

t

>1, so we adjust the average

for that day downward by a proportion of typical expenditure.

Conversely, if it is more likely to fall on a weekend than typical,

then r

t

<1, so we adjust the average for that day upward. Based

on this, we compute “tax refund-triggered additional spending”

over any period between day s and day t by:

Or, equivalently:

This reflects the fact that any dierence in average expenditure

in the period from day s to day t compared with an equivalent

number of days during the pre-refund period might be an

artifact of dierences in weekday versus weekend composition.

We use the r

τ

x

p

term in the summation above to sweep out that

artifactual component. Finally, we note that the adjusted (green)

series in Figure 6 is countercyclical with the unadjusted (blue)

series during the period prior to the refund payment. This

indicates that this approach somewhat over-corrects, in that it

20

“pushes” more expenditure from days that are most likely to fall

on weekdays to days that are most likely to fall on weekends.

This makes our approach conservative in the sense that it likely

underestimates the impact of the refund on the spike at day 0.

We also used an approach that computes seven separate

correction factors each of which inflates or deflates expenditure

on a day of the week, instead of a single weekday-versus-

weekend inflator. The results reported here were substantively

identical using this alternative approach. We also computed

additional spending using the actual (unadjusted) series, and

found all results to be substantively the same as what we have

reported here.

7 We decompose the growth in average spending per account

per day in logarithms. The natural logarithm of the ratio of

average daily spending during the 75 days after the refund

payment to average daily spending prior to the refund payment

(0.18) is itself equal to the sum of two logarithms. The first is

the logarithm of the ratio of the average payment sizes (0.11),

and the second is the logarithm of the ratio of the number

of payments (0.07). We use this to assign the “contribution”

of these two components to the overall growth in the

average—0.11/0.18, or 59 percent of the growth, is “contributed”

by growth in the average payment size, and 0.07/0.18, or 41

percent of the growth, is “contributed” by growth in the number

of payments.

8 Healthcare services include doctors, dentists, hospitals, nursing

service providers, ambulance service providers, medical

laboratories, opticians, optometrists, chiropractors, and “other”

healthcare services. Goods include all purchases at drug stores,

medical equipment suppliers, orthopedic goods and prosthetic

device suppliers, and hearing aid providers. Some overlap exists

between healthcare service providers and goods providers; for

example, a payment to an optometrist may be for a glaucoma

screening or for a pair of eyeglasses, or conversely a payment to

a drug store may be for a walk-in clinic visit.

9 We infer whether someone has a credit card on the basis of

whether we ever observe a credit card payment prior to the

arrival of the tax refund.

Back to Contents

Suggested Citation

Farrell, Diana, Fiona Greig, and Amar Hamoudi. "Deferred Care: How Tax Refunds Enable Healthcare Spending."

JPMorgan Chase Institute, 2018.

This material is a product of JPMorgan Chase Institute and is provided to you solely for general information purposes.

Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may dier

from the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research Department or other departments or divisions

of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its aliates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information has

been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its aliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively

J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this

material and are subject to change without notice. The data relied on for this report are based on past transactions and may not be

indicative of future results. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any particular client

and is not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies for a particular client. This

material does not constitute a solicitation or oer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

©2018 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved. This publication or any portion hereof may not be reprinted, sold, or redistributed

without the written consent of J.P. Morgan. www.jpmorganchaseinstitute.com