AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF

Barbara R. Rowe for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

in Family Resource Management presented on November 25,

1985.

Title:

The Economic Consequences of Divorce in Oregon

After Ten or More Years of Marriage.

Abstract approved:

,Redacted for Privacy

Alice Mills Morrow

The financial aspects of divorce are of great im-

portance to the growing numbers of men, women, and chil-

dren who live with the consequences of economic deci-

sions made at dissolution.

The purpose of this study

was to provide data on the economic aspects of

divorce

in Oregon after ten or more yearsof marriage; to de-

termine what assets were owned, how those assets were

valued for the purpose of division, which assets were

allocated to wives and which were allocated to husbands,

the factors that affected the allocation, and the effect

of asset division on the post-divorce economic well-

being of wives and husbands.

The sample was drawn from final divorce decrees

for marriages lasting ten or more years filed between

July 1983 and June 1984 in the Oregon counties of

Multnomah, Clackamas, and Washington.

Interviews were

conducted with 67 women and 49 men.

Most of these couples after ten or more years of

marriage, owned homes and tangible personal property,

most often furniture and a car.

Pensions were the most

frequently owned intangible personal property.

The

greater the value of an asset the more likely it was to

be valued objectively.

Assets were allocated fairly

equally between spouses.

However, this did not have the

effect of putting husbands and wives in similar economic

positions.

When predivorce and postdivorce household

incomes were compared, almost all of the movement toward

lower income was accounted for by wives.

Mothers were more likely than fathers to have cus-

tody of children.

When there were children under age

18, child support was usually awarded.

However, the

monthly amount of child support was less than one-half

of the estimated monthly cost of raising a child, lead-

ing to the conclusion that the custodial parent bears a

disproportionate share of the cost of raising a child.

While the allocation of property between divorcing

spouses is a concern that cannot be ignored, an equally

important concern in these marriages lasting ten or more

years is the lack of income-earning ability of the

wives.

Copyright by Barbara R. Rowe

December 30, 1985

All Rights Reserved

THE ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF DIVORCE IN OREGON

AFTER TEN OR MORE YEARS OF MARRIAGE

by

Barbara R. Rowe

A THESIS

submitted to

Oregon State University

in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the

degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Completed November 25, 1985

Commencement June 1986

APPROVED:

Redacted for Privacy

Associate Professor of Family Resource Management in

charge of major

Redacted for Privacy

-/

Head of Department of Family Resource Management

Redacted for Privacy

titDean of Grate School

Date thesis is presented

-7-

November 25, 1985

Typed by Sandra Warren for

Barbara R. Rowe

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to especially thank Dr. Alice Mills Morrow,

my major professor, who gave up nights, weekends, holi-

days and vacations to see me through a Master's by-pass,

proposal, data collection, and dissertation.

Her cir-

tique of my research ideas and sharp editorial skills

have always made the finished product better.

I would also like to extend my sincere appreciation

to my graduate committee:

Dr. Arthur Gravatt, Dr. Gary

Tiedeman, Dr. Patricia Wells, and former committee mem-

ber Dr. Virginia Haldeman, for their support and con-

stant encouragement during my class work and the prepa-

ration of this dissertation.

A special debt of gratitude is owed Dr. Geraldine

Olson who served as the "guiding hand" throughout my

graduate program and research.

I was so lucky to have

her wise counsel and assistance.

Sincere appreciation is also extended to Ms. Evelyn

Leasher of Kerr Library, who kept an eye open for arti-

cles I could use in my research; Mr. Larry Gildea for

believing in me; Dr. Helen Berg of the Survey Research

Center, who helped me understand sampling techniques

and gave me a better grasp of research methods; Sandra

Warren for the thousand favors she did for me; and Mr.

Tom Gus, without whom my "n" would be half as big.

In addition, I wish to thank the men and women who

participated in this study for their time, and for the

deeper understanding they gave me of the divorce pro-

cess.

I can never repay my mother and my sister, Edith,

for their financial and moral support; nor my sister

Virginia, who provided ten months of free room, board,

and emotional support.

Lastly, a very special thank you to my children;

Alice, Tom, and Mike, without whose understanding and

love these years of graduate study would not have been

possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION 1

Need for the Study

4

Statement of Purpose

5

Objectives of the Study 6

Delimitations of the Study 6

Limitations of the Study

6

Definition of Terms

7

Research Hypotheses 8

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE 11

Divorce Law, In General

11

Property Division

15

Spousal Support

20

Child Custody and Child Support 26

Oregon Law

32

The Economics of Female-Headed Households

39

Loss of Economies of Scale

41

Poverty as a Result of Divorce

41

Public Assistance

43

Fewer Earners

45

Labor Force Participation

46

Summary

47

CHAPTER III

DESIGN OF STUDY AND METHODOLOGY

53

Development of the Instrument

53

Selection of the Sample

54

Collection of the Data

56

Data Analysis Procedure

57

Hypothesis One

58

Hypothesis Two

59

Hypothesis Three

59

Hypothesis Four

60

Hypothesis Five

61

Hypothesis Six

63

Summary of Statistical Analyses

65

CHAPTER IV

FINDINGS

66

Description of the Respondents

66

Representativeness of Respondents

66

Duration of the Marriage

68

Age of Divorcing Couples

69

Number of Minor Children

70

Sex of Petitioner

71

Characteristics of the Couples

73

Education

74

Employment

75

Assets

76

Income

77

The Settlement Process

79

Division of Property

82

Spousal Support

88

Decisions Pertaining to Children

90

Economic Well-Being After Divorce

94

Hypothesis Testing

98

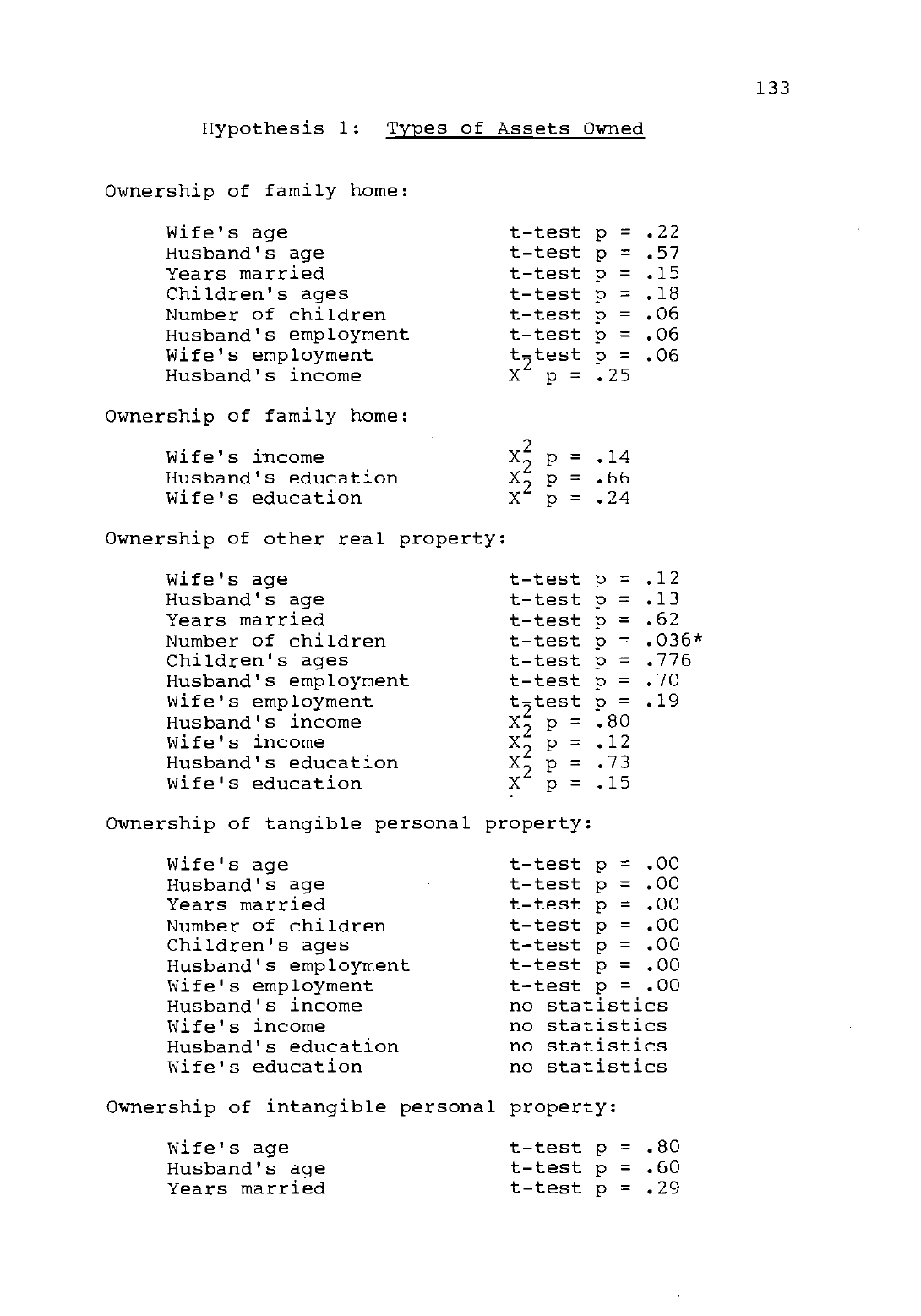

Ownership of Assets

98

Dollar Value of Assets

102

Valuation of Assets

107

Allocation of Assets

110

Equitable Distribution

118

Post-Divorce Economic Well-Being

122

Summary of Statistical Analysis

132

Characteristics of the Sample

132

CHAPTER V

IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

138

Recommendations for Further Study

148

TABLE OF CASES

151

REFERENCES

152

APPENDIX A:

Introductory Letter

163a

APPENDIX B:

Court Data Collection Form

164a

APPENDIX C:

Research Instrument

165a

Table

4.1

Table 4.2

Table 4.3

Table 4.4

Table 4.5

Table 4.6

Table

4.7

Table 4.8

Table 4.9

Table 4.10

Table 4.11

Table 4.12

Table 4.13

Table 4.14

Table 4.15

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Analysis of variance of duration of

marriage for those who were inter-

viewed, those who were not inter-

viewed, and those who refused to

participate

68

Analysis of variance of wife's age

for those who were interviewed,

those who were not interviewed, and

those who refused to participate

69

Analysis of variance of husband's

age for those who were interviewed,

those who were not interviewed, and

those who refused to participate

70

Analysis of petitioner's sex for

those who were interviewed, those

who were not interviewed, and those

who refused to participate

72

Education levels of husbands

and wives

75

Employment of husbands and wives 76

Monthly income of husbands and wives

at the time of the divorce

78

Total household income prior to the

divorce 79

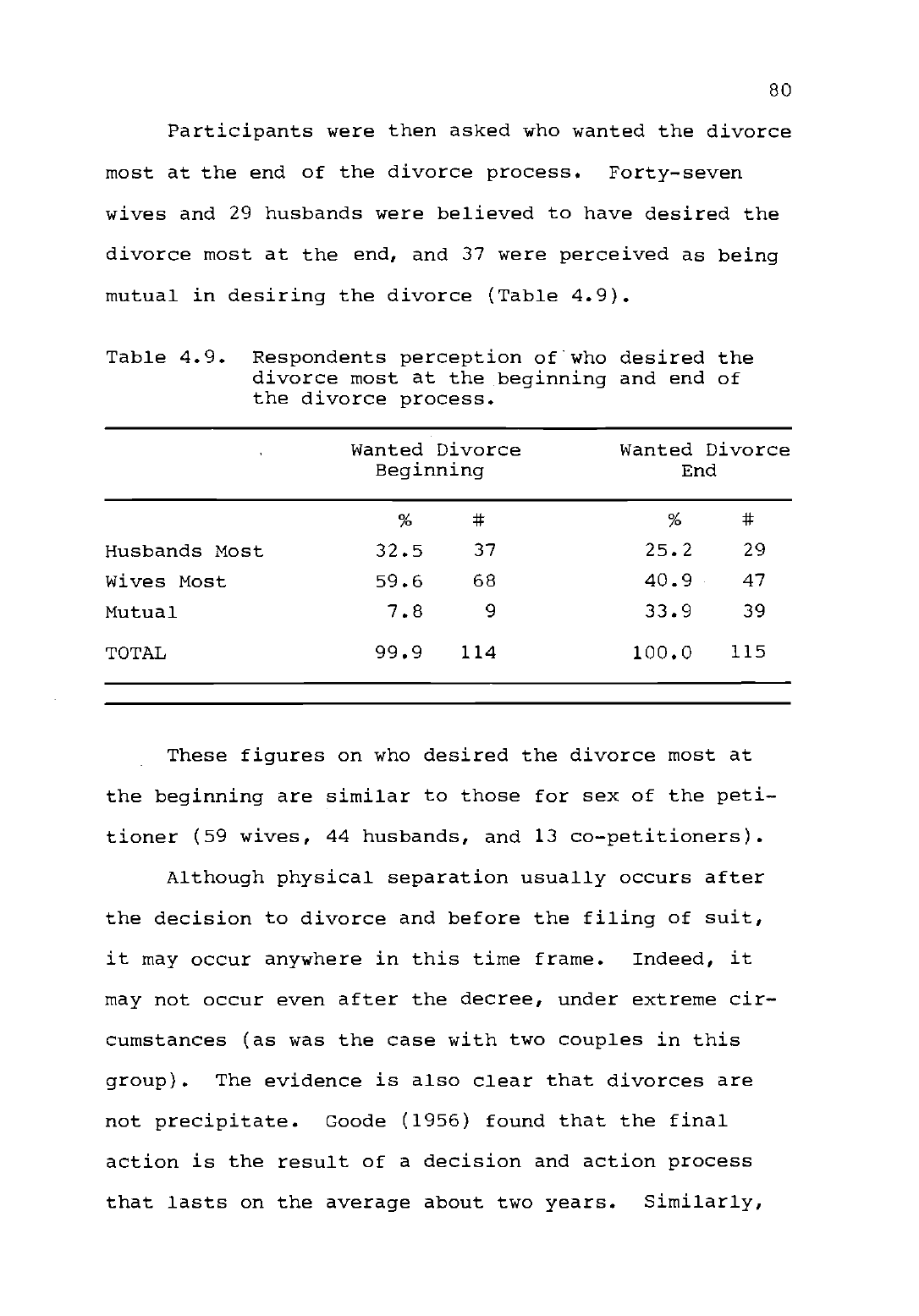

Comparison of responses for husbands and

wives regarding desire for the divorce.

80

Retention of family home

83

Estimate of division

87

Level of satisfaction with settlement 87

Attitude toward present economic

situation 95

Present household income of

respondents

96

Largest source of present income

97

Table 4.16

Attitude toward emotional situation ... 97

Table 4.17

Number of minor children for those who

owned other real property and those who

did not own other real property

99

Table 4.18

Ownership of intangible personal

property by wife's employment

history

101

Table 4.19

Ownership of intangible personal

property by wife's education level .... 102

Table 4.20

Correlations between selected

characteristics of divorcing couples

and the net dollar value of assets .... 106

Table 4.21

Methods of asset valuation used by

divorcing couples

109

Table 4.22

Wives keeping family home by custody

of children

112

Table 4.23

Husbands keeping family home by custody

of children

112

Table 4.24

Retention of other real property by

wife's age

113

Table 4.25

Retention of other real property by

marital duration

114

Table 4.26

Retention of other real property by

husband's employment

114

Table 4.27

Retention of tangible personal property

by children's custody

116

Table 4.28

Retention of tangible personal property

by who wanted divorce most at

the end

117

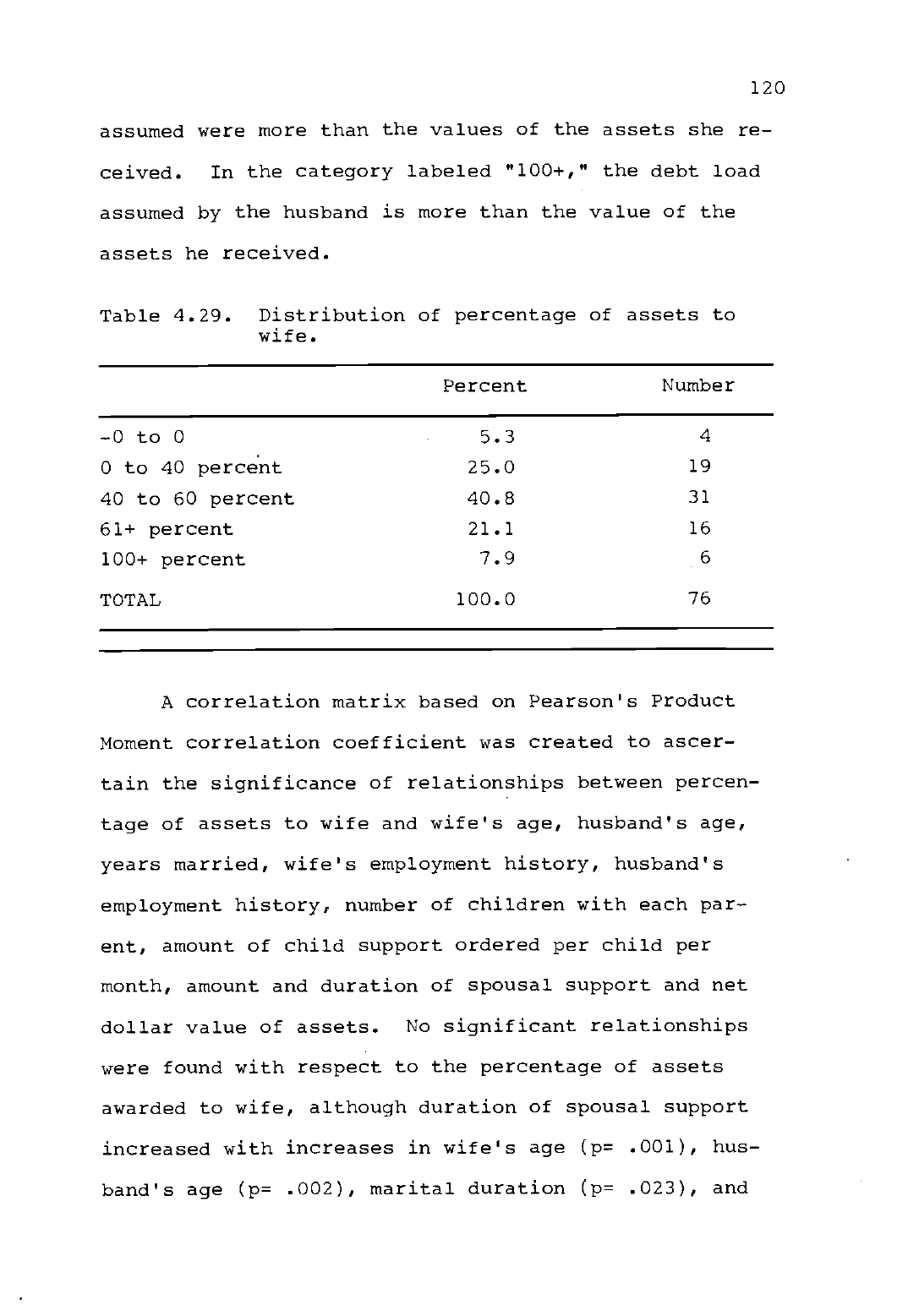

Table 4.29

Distribution of percentage of

assets to wife

120

Table 4.30

Percentage of assets to wife by owner-

ship of family home

122

Table 4.31

Multiple stepwise regression of selected

variables on post-divorce economic

well-being

125

Table 4.32

Respondent's attitude toward post-divorce

economic well-being by present

employment

126

Table 4.33

Respondent's attitude toward post-divorce

economic well-being by present

employment and sex

127

Table 4.34

Respondent's attitude toward post-divorce

economic well-being by whether couple made

decisions as to asset allocation

131

Table 4.35

Analysis of variance of respondent's

attitude toward post-divorce economic

well-being by whether couple made

decisions as to asset allocation and

sex

131

Table 4.36

Percentage of assets to wife by whether

couple made decisions as to asset

allocation and sex

132

THE ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF DIVORCE IN OREGON

AFTER TEN OR MORE YEARS OF MARRIAGE

I. INTRODUCTION

Nationally, and in Oregon, there has been a dramatic

increase in the incidence of divorce (Gravatt and Hunt,

1979).

In a single year, 1981, 2,438,000 adults and

1,219,000 children, 2 percent of the total United States

population were affected by divorce (Statistical Abstract,

1982-83).

The 17,762 divorces and annulments in Oregon

in 1980 set a new record, and the rate per 1,000 was 6.8,

double what it had been in 1965 (Oregon Vital Statistics,

1980).

In human terms, a significant number of our popu-

lation has had a direct experience with divorce, either

in their own marriages or in their parents' or childrens'

marriages (Albrecht, 1980; Wiseman, 1975). The importance

of divorce lies not only in its numerical growth but also

in its increasing social, psychological, and economic

implications for families, individuals, and society

(McGraw, Sterin and Davis, 1982; Weitzman, 1981).

Since 1970, the number of families maintained by a

woman alone has increased by more than 53 percent to 9.4

million (Marital Status and Living Arrangements, 1983).

Female-headed families represent the largest subgroup of

the population living below the poverty level (Wattenberg

and Reinhardt, 1979). Most of the growth in female-headed

families has been related to increased marital disruption

2

and to the higher proportion of divorces which involve

children (Ross and Sawhill, 1975).

At least four studies have concluded that the poorer

a family is, the more likely the parents are to divorce

(Carter and Glick, 1970; Cutright, 1974; Glick and Norton,

1976; Goode, 1956). What is not known is the extent to

which divorced mothers are poor because they were poor

before the divorce and the extent to which they are poor

because of the divorce.

In all divorce actions, the court has a legal respon-

sibility to insure that the resolutions are equitable and

in the best interests of the parties (McGraw, Sterin and

Davis, 1982). Yet, very little is known about actual

awards and agreements. This lack of systematic informa-

tion makes it impossible for the parties, legislators or

the courts to make an accurate analysis of the impact of

divorce or to alter its effects.

There are five major decisions where divorcing cou-

ples may need to reach agreement: child custody, child

visitation, child support, alimony and division of prop-

erty (Kressel, Lopez-Morillas, Weinglass and Deutsch, 1978).

Recent studies using court records to analyze property

divisions have been "hampered by the fairly large amount

of missing information in the case record" (McGraw, Sterin

and Davis, 1982) or have been linked to state laws requiring

an equal division of community assets (Weitzman, 1981),

restricting the generalizations to a small minority of

3

jurisdictions.

For those cases in which information was

available, gender appeared to have an independent effect

on both the amounts and types of marital assets awarded

(i.e., wives usually received homes and furniture, hus-

bands received bank accounts, stocks, and businesses).

Most states, including Oregon, use the standard of

a "just" or "equitable" division of assets. This em-

powers the courts to distribute property regardless of

how title is held in order to achieve equity and justice

between the parties (Patterson, 1981).

This standard

allows a great deal of judicial discretion in the divi-

sion of marital property (Weitzman, 1981).

In addition,

Oregon law makes no distinction between assets acquired

before the marriage and those acquired after. Neither

is there any distinction regarding assets acquired after

the marriage by gift or inheritance.

The assets consid-

ered at dissolution are all of the property belonging to

either party or both parties, regardless of when or how

acquired, creating a "universal community" for division

(Cantwell, 1980).

Thus, Oregon is an ideal environment

for the collection of objective data regarding the prev-

alence and recipiency of property awards and for explor-

ation of the impact of property division on the post-

dissolution economic outcomes of divorcing families.

4

Need for the Study

The economic consequences of divorce are a major

social problem in the United States today.

Reforms which

were instituted in the 1970s have shifted the focus of the

legal process of divorce from moral questions of fault and

responsibility to economic issues of ability to pay and

financial need (Bahr, 1983; McGraw, Sterin and Davis, 1982;

Weitzman, 1981).

The increased importance of these finan-

cial issues suggests the need for more complete information

to aid judges, attorneys, and divorcing couples in making

economically sound decisions (Weitzman, 1981).

However, divorce as a primary subject of study has

been ignored to a great extent (Kitson and Raschke, 1981).

Prince-Bonham and Balswick (1980), in a decade review of

family literature, found that much of what we do know about

divorce has been a by-product of research on other topics

such as mental health and life satisfaction. Findings

based on these data sources provide more knowledge about

who divorces than what happens to them after divorce. Kit-

son and Raschke (1981), in a similar review, concluded that

one of the issues that needs to be addressed in future re-

search is analysis of the variables related to divorce ad-

justment, which include economic problems.

The numerous decisions and changes in life-style that

accompany most divorces present important challenges for

all the family-helping professions.

The economic aspects

5

of divorce are of great importance to the growing numbers

of men, women, and children who will live with the conse-

quences of economic decisions made at the time of dissolu-

tion.

Statement of Purpose

The purpose of this study is to provide data on the

economic aspects of divorce in Oregon after ten or more

years of marriage:

to determine how divorcing couples and

the courts value and allocate marital assets at dissolu-

tion; to look at the effects of marital duration, the ages

of the parties, their employment histories and earning

capacities, education levels, and the custodial and support

provisions of the decree on the valuation and allocation of

marital assets; and to determine whether or not the valua-

tion and division of marital property affects the post-

divorce economic well-being of husbands, wives, and their

children.

A study focusing on the financial aspects of divorce

settlements should provide information which will assist

divorcing couples, attorneys, the courts, and policy makers

concerned with the divorce process and the security and

economic well-being of families.

This information should also provide a frame of ref-

erence for developing educational programs and materials

in the areas of family economics and home management and

for strengthening marital, financial, and employment coun-

6

seling programs.

Objectives of the Study

The objectives of this study were:

1. to determine the types and total dollar

value of assets owned by divorcing couples;

2. to identify the methods used in valuing

assets for the purpose of division at

divorce;

3.

to identify types of assets allocated to

wives and types of assets allocated to

husbands;

4. to identify the factors affecting the types

of assets allocated to wives and the types

allocated to husbands;

5. to determine the percentage of the total

dollar value of assets allocated to wives

and the percentage allocated to husbands

at divorce; and

6.

to assess the effects of asset division on

the post-divorce economic well-being of

husbands and wives.

Delimitations of the Study

1.

The study is limited to the investigation of

divorces occurring after ten or more years of

marriage.

2.

The study is restricted to individuals granted

divorces in three Oregon counties.

Findings

can be generalized only to these respondents.

3.

The study is confined to those potential re-

spondents with a verifiable phone number and

address who agreed to be interviewed.

4.

The study is limited to divorces whose final

decrees were granted between July 1983 and

June 1984.

Limitations of the Study

1.

Potential respondents who declined to be inter-

viewed may be different from those who did

agree to be interviewed.

2.

Information provided by respondents is as

accurate as their recall will allow.

7

Definition of Terms

Assets - real and personal property:

real prop-

erty includes land and that which is affixed to it

(Black, 1983); personal property includes pensions,

stocks, bonds, and other investments, businesses, ve-

hicles, household durables, bank accounts, and life

insurance with a cash value.

Equitable distribution - for the purpose of this

study a division of assets is considered equitable when

either party receives no more than sixty percent or no

less than forty percent of the fair market value of all

assets legally and beneficially acquired during marriage

by either husband or wife, or both, regardless of legal

title.

Employment history

number of years in the labor

force, whether continuous or discontinuous, whether

part or full time paid employment.

Objective valuation - assets will be considered

objectively valued if some data were used to arrive at

a fair market value (e.g., independent appraisal, prop-

erty tax records, Blue Book, classified advertisements,

retirement account statements, bank statements).

Post-divorce economic well-being

defined for

this study by respondent's answer to the question, "Do

you think your economic situation now, as compared to

before the divorce, is better, somewhat better, about

the same, somewhat worse, or worse?"

8

Subjective valuation - assets will be considered

subjectively valued if no data were used to arrive at

a fair market value.

Types of assets - for the purpose of this study,

each asset has been placed into one of these four cate-

gories:

family home; other real property; tangible

personal property (e.g., cars, other vehicles,

fur-

niture and household durables) and intangible personal

property (e.g., bank accounts, stocks and bonds, pen-

sion and retirement benefits, life insurance, and

businesses or professional practices).

Research Hypotheses

Hypotheses for this study are as follows:

Hot:

The types of assets owned by divorcing couples

have no relationship to:

(a) age of wife

(b) age of husband

(c) duration of marriage

(d) employment history of wife

(e) employment history of husband

(f) wife's monthly income at time of divorce

(g) husband's monthly income at time of

divorce

(h) number of minor children

(i) ages of minor children

(j) education level of wife

(k) education level of husband

H 2:

There is no difference between the dollar value

0

of assets owned by divorcing couples and:

(a) age of wife

(b) age of husband

(c) duration of marriage

(d) wife's employment history

(e) husband's employment history

(f) wife's monthly income at time of divorce

(g) husband's monthly income at time of

divorce

9

(h) number of minor children

(i) ages of minor children

(j) education level of wife

(k) education level of husband

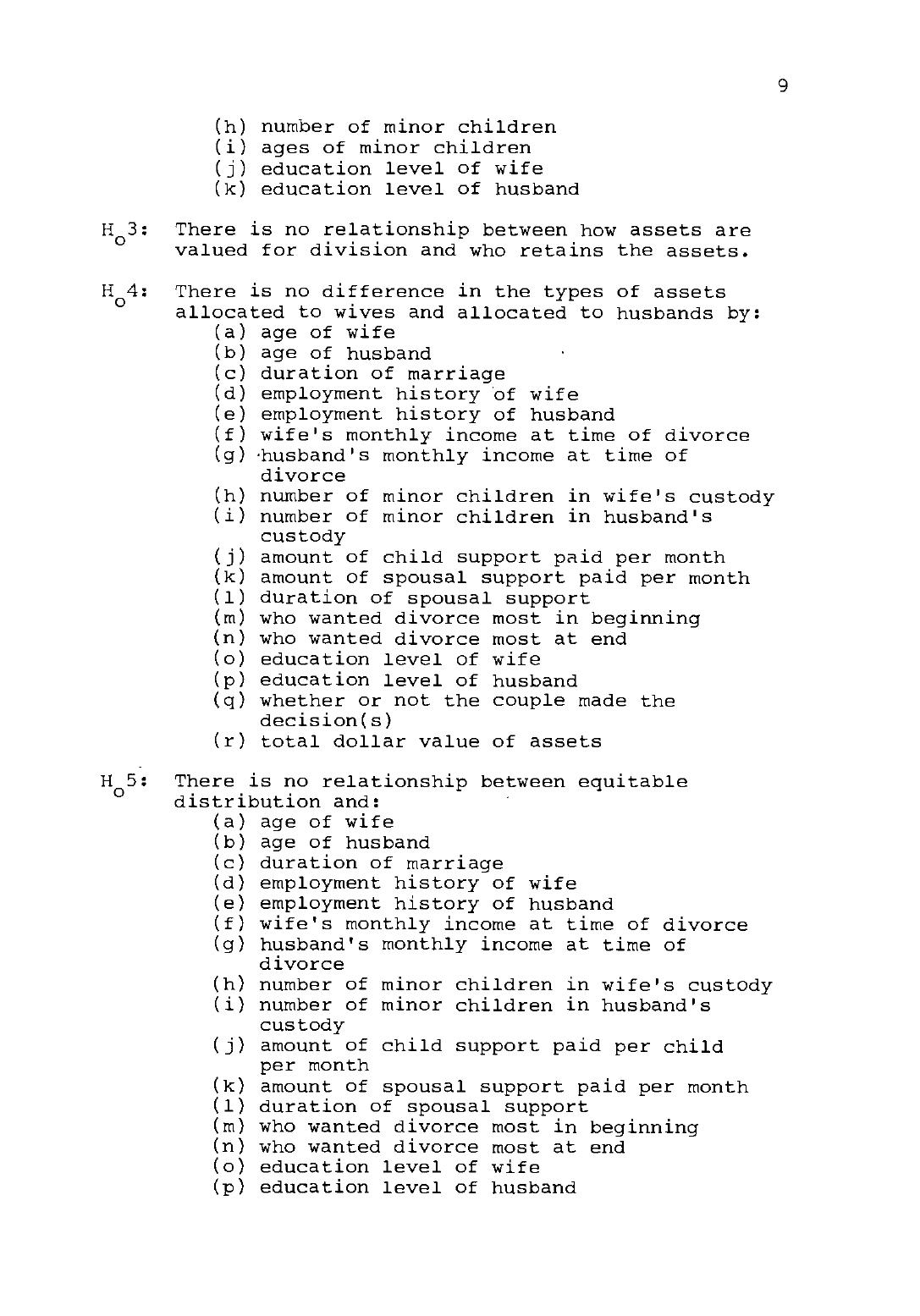

H

o

3:

There is no relationship between how assets are

valued for division and who retains the assets.

H

o

4:

There is no difference in the types of assets

allocated to wives and allocated to husbands by:

(a) age of wife

(b) age of husband

(c) duration of marriage

(d) employment history of wife

(e) employment history of husband

(f) wife's monthly income at time of divorce

(g) thusband's monthly income at time of

divorce

(h) number of minor children in wife's custody

(i) number of minor children in husband's

custody

(j) amount of child support paid per month

(k) amount of spousal support paid per month

(1) duration of spousal support

(m) who wanted divorce most in beginning

(n) who wanted divorce most at end

(o) education level of wife

(p) education level of husband

(q) whether or not the couple made the

decision(s)

(r) total dollar value of assets

H

o

5:

There is no relationship between equitable

distribution and:

(a) age of wife

(b) age of husband

(c) duration of marriage

(d) employment history of wife

(e) employment history of husband

(f) wife's monthly income at time of divorce

(g) husband's monthly income at time of

divorce

(h) number of minor children in wife's custody

(i) number of minor children in husband's

custody

(j) amount of child support paid per child

per month

(k) amount of spousal support paid per month

(1) duration of spousal support

(m) who wanted divorce most in beginning

(n) who wanted divorce most at end

(o) education level of wife

(p) education level of husband

10

(q) whether or not the couple made the

decision(s)

(r) whether or not a family home was owned

(s) whether or not other real estate was

owned

(t) whether or not tangible personal property

was owned

(u) whether or not intangible personal prop-

erty was owned

(v) total dollar value of assets

Hob:

The post-divorce economic well-being of husbands

and wives has no relationship to:

(a) age of respondent

(b) duration of marriage

(c) respondent's employment history

(d) thousehold income prior to divorce

(e) number of minor children with respondent

(f) amount of child support paid/received by

respondent

(g) amount of spousal support paid/received

by respondent

(h) if respondent wanted divorce most at

beginning

(i) if respondent wanted divorce most at end

(j) education level of respondent

(k) whether or not couple made the decision(s)

(1) net amount of assets received by respondent

(m) sex of respondent

(n) if respondent presently employed

(o) respondent's present household income

11

II.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Divorce Law, In General

Divorce law is closely related to a society's view

of marriage and the family (Clark, 1968).

The tradi-

tional view of marriage in the United States recognized

the husband as the primary decision maker who provided

economic support for the wife and children. The role

of the wife was caring for the household and children

(Glendon, 1980). Marriage was a permanent and cherished

union that the state had to protect and preserve.

The traditional view of divorce in the United

States was that a divorce could be obtained only if one

spouse committed a marital offense, such as adultery,

cruelty, or desertion, giving the other spouse a legal

basis, or grounds, for such action (Eisler, 1977).

Traditional divorce was based on an adversary proceeding

requiring that one party be guilty or responsible for

the divorce and the other be innocent (Kay, 1971).

Being found guilty or innocent had financial conse-

quences.

Only an innocent wife could receive alimony--a

means of continued support--and only a guilty husband

had to pay alimony (Crozier, 1935; Karowe, 1974).

Property awards were also linked to fault.

In most

states the court had to award more than half of the

property to the innocent party. This led to heated

accusations and counteraccusations of wrongs to obtain

12

a better marital settlement (Hogobloom, 1971).

At

divorce, the husband also remained responsible for the

children's economic support and all states gave prefer-

ence to a virtuous wife as the "natural and proper"

parent after divorce (Mnookin, 1975).

By the mid-nineteenth century, in the United States,

conservatives concluded that divorce was symptomatic of

a national moral crisis (Haien, 1980; Rheinstein, 1972).

Between 1884 and 1947, conservative reformers made many

efforts to abolish or stiffen traditional divorce laws

which were regarded as too liberal.

Since Congress could not be moved to propose an

amendment to the Constitution that would have extended

Federal legislative power to the field of family life,

conservatives began a parallel effort to restrict divorce

by coordinating state legislation.

To this end, the

National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State

Laws was created.

At its first meeting, the body's

stated motive was to "stem the rising tide of divorce"

through "improvement and uniformity" of existing state

marriage and divorce laws (Rheinstein, 1972).

After the Commission's founding in 1892, the tra-

ditional view of marriage and divorce began to change.

It became generally agreed that dead marriages should

end, family assets should be fairly divided, economic

circumstances should govern alimony or maintenance, and

children, where possible, should know and associate with

13

both parents (Freed and Foster, 1983).

In 1965, the

Commission's co-chairmen suggested the abandonment of

traditional grounds for divorce and recommended that a

new approach to the administration of divorce laws be

researched and drafted (Rheinstein, 1972).

In 1967, the Ford Foundation granted funds to the

Commissioners to "assist in the research, deliberation,

and drafting necessary for promulgation of a comprehen-

sive family law" (Cheadle, 1981). Professor Robert J.

Levy of the University of Minnesota prepared a mono-

graphic study on marriage and divorce, which served as a

working basis for the Committee. In his report, Levy

concluded that American divorce law should be "predicated

solely and exclusively upon the ground of irremedial

marriage breakdown" (Rheinstein, 1972).

In 1970, the proposed Uniform Marriage and Divorce

Act (UMDA) was approved by the National Conference of

Commissioners (Rheinstein, 1972). In addition to adopt-

ing "no-fault" marriage breakdown as the sole ground for

divorce, it proposed new standards for alimony and prop-

erty division.

The Family Law Section of the American Bar Associa-

tion (ABA) withheld approval of the UMDA for four years.

The Bar attacked the statute on three grounds: the ease

and speed with which a divorce could be granted; the

absence of reconciliation provisions; and the proposed

provisions of the property distribution section (Podell,

14

1973). The ABA favored an "equitable distribution" pro-

vision giving divorce courts the power to distribute all

the property of the spouses, marital or separate.

Because of the ABA's objections, a section allow-

ing distribution of all property was written. This be-

came the provision "recommended generally for adoption"

by the ABA and is referred to in the UMDA as Alternative

A (Cheadle, 1981).

It provides that the property avail-

able for division is "the property and assets belonging

to either or both, however and whenever acquired, and

whether the title is in the name of husband, or wife,

or both" (Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act, 1982).

No

distinction is made between assets acquired before the

marriage and those acquired after marriage. Neither is

there any distinction regarding assets acquired by gift

or inheritance after the marriage. This permits the

broadest possible distribution of all assets held by

either spouse at the time of dissolution (Freed and

Foster, 1984). The essence of this alternative was

adopted by the Oregon Legislature in 1971.

The original guidelines providing for property

division were retained with minor changes as Alternative

B, because Commissioners from community property states

protested that their jurisdictions preferred to retain a

distinction between community and separate property

(Cheadle, 1981).

Alternative B describes marital prop-

erty as "all property acquired by either spouse after

15

the marriage except for property acquired

by gift, be-

quest, devise, or descent" (Uniform Marriage

and Divorce

Act, 1982).

This provision includes a presumption

that

all property acquired by either

spouse after the mar-

riage and prior to dissolution would

be marital property

"regardless of whether title is held individually

or by

the spouses in some form of co-ownership"

(Cantwell,

1980).

Both alternatives include other

factors to be

considered in making

a division, such as the contribu-

tions of the homemaker-spouse,

the custodial provisions

of the decree, and the economic circumstances

of each

spouse (Cantwell, 1980; Cheadle, 1981).

The Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act

met with exten-

sive criticism and was enacted by

only five states.

But

its basic concepts are

now incorporated in the statutes

of most states (Connell, 1981).

On July 1,

1985, South

Dakota became the fiftieth state to

adopt a form of no-

fault divorce (Americans for Legal

Reform, 1985; Freed

and Walker, 1985).

Regardless of the property distribu-

tion section, states have adopted

UMDA principles and

enacted legislation requiring the courts

to look beyond

title in deciding how much each

spouse should share in

the assets to be distributed (DiLeo and

Model, 1982).

Property Division

Historically, only two approaches

to dividing prop-

erty upon divorce existed:

the separate property system

16

of common law and the community of assets created in

community property jurisdictions.

Under common law, upon marriage, all the wife's

personal property became the property of her husband.

She did not lose title to real property owned by her

prior to the marriage, but her husband was entitled to

the rents and profits from her lands without account-

ability to her. If the marriage produced a child born

alive, the husband was entitled to income from his wife's

lands for the rest of his life.

During the marriage,

the wife could not sue or be sued on her own behalf; and

her husband was entitled to all of her earnings (Clark,

1968; Johnston, 1972).

In exchange, the wife received

the benefit of the husband's duty to support the family

in an amount determined by him. In addition, she was

entitled to one-third of the husband's real property if

she survived him (Bartke and Zurvalec, 1980; Karowe,

1974).

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, leg-

islation known as the Married Women's Property Acts was

passed in all of the common law states (Cheadle, 1981).

These laws gave women the right to own and control their

separate property, including their earnings from employ-

ment outside the home (Cantwell, 1980; Cheadle, 1981;

Kanowitz, 1969).

Traditional forms of joint ownership

continued, but if title was held in the name of one

spouse, that property was legally shielded from the other

17

(Cheadle, 1981).

These new freedoms did little to improve the eco-

nomic situation of most wives.

No property rights arose

during marriage by virtue of the marriage itself

(Krauskopf, 1976).

A spouse retained all the property

he or she earned or inherited during the course of the

marriage. The other spouse had no right or interest in

his or her partner's income or separate property (Weitz-

man, 1981). Upon divorce, real inequities existed if

the family assets had been acquired and held in the name

of the wage-earning husband (Wirth v. Wirth, 1971). The

courts had no power to order transfers or divisions of

separately held property (Krauskopf, 1976). Only joint-

ly held property was subject to distribution on dissolu-

tion (Greene, 1979).

In the community property jurisdictions, all prop-

erty owned by a married couple was classified as either

community property or separate property.

Separate prop-

erty consisted of all property owned by a spouse before

the marriage, any property obtained after the marriage

by way of gift or inheritance, and other property

acquired by a spouse during the marriage which could be

traced back to separate property (Cheadle, 1981; Greene,

1979). Each spouse retained the right to own, manage,

and control such separate property during the marriage

(Greene, 1979).

Community property consisted of all

other property acquired after marriage by either husband

18

or wife.

Each spouse owned a present, vested, undivided

one-half interest in the community property (Greene,

1979).

Despite the equality-of-sharing philosophy of com-

munity property laws, until recently, the husband had

the power to make virtually all management decisions in-

volving that property (Cheadle, 1981). He could sell

it, mortgage it, and in three states, give it away with-

out his wife's consent (Younger, 1973).

Any debt in-

curred by a married man was presumed to be a community

obligation and community property could be attached by

his creditors.

The wife needed to prove that she was

acting for the community in order to pay an obligation

from community assets (Karowe, 1974).

Upon divorce in community property states, the

court "disregarded" title and determined whether the

community owned the property or whether it was the sep-

arate property of one of the spouses (Patterson, 1981).

Each spouse was entitled to one-half of all the marital

property regardless of the monetary contribution each

person might have made towards its purchase (Krauskopf,

1975).

Separate property was generally not subject to

division, but remained with its original owner (Brake,

1982).

Today there are three general methods of dividing

property at divorce; the community property or "deferred"

community property approach, common law-title statutes,

19

and common law equitable distribution systems.

In community property states (Arizona, Arkansas,

California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas,

Washington, and the territory of Puerto Rico), property

is classified as either separate property or "marital"

property. Marital property is divided along the lines

of "equal in value" or "equitable."

The traditional

concept of fault has been abandoned, although in some

states (Arkansas, Idaho, Nevada, Texas, and Puerto Rico)

marital misconduct may decrease or eliminate the guilty

party's share of the community property (Freed and

Walker, 1985).

In the one common law-title state (Mississippi)

only jointly held property is distributed at divorce.

As to property not jointly held during the marriage,

the person with title during the marriage continues

ownership at divorce.

The remaining states (including Oregon) are equi-

table distribution states.

At divorce, courts permit a

spouse who has made contributions toward the acquisition

of property to claim an equitable interest in such prop-

erty, regardless of how it is titled (Freed and Walker,

1985). An increasing number of states recognize as con-

tributions being a homemaker and parent. Equitable dis-

tribution laws allow the courts to distribute property

according to the court's view of what is "equitable,"

taking into account the contributions of both parties,

20

regardless of the extent to which they were measured in

the marketplace (Foster and Freed, 1974).

Equitable

distribution does not guarantee any property interest to

a wife, but gives her the possibility of acquiring an

interest in the marital assets if the court views such

a decision as "just and proper."

Spousal Support

In traditional marriage, the primary obligation to

provide financial support to the family rested upon the

husband "so long as he is able" (Clark, 1968). This

duty was placed on the husband because at common law he

owned and controlled all his wife's property, all her

earnings, and her services. Even after the Married

Women's Property Acts permitted a wife control of her

separate property, it did not relieve the husband of his

duty to support her (Clark, 1968).

The same marital

rules functioned in the community property states,

except the wife's earnings, but not her separate prop-

erty, was subject to support obligations (Karowe, 1975).

This rule had limited practical significance in an

ongoing marriage for the courts refused in intervene

while husband and wife lived together (Kanowitz, 1969).

The wife had no legal recourse to require the husband

to provide support unless she left him and set up a

separate household (Krauskopf, 1977).

One explanation for the court's refusal to recog-

21

nize a remedy for the wife's right to support while the

parties lived together was that of keeping the parties

together.

In 1962, a New York court justified its re-

fusal to grant a support order to a wife who was still

living with her husband by saying, "The court should not

encourage a separation by granting temporary support in

which event the wife would move from the marital resi-

dence, if otherwise she might not" (Baker v. Baker,

1962).

Another purpose was the court's reluctance to

become involved "as budget makers for family units"

(Commonwealth v. George, 1948).

Private contracts be-

tween husband and wife which change the nature of his

support obligation have been ruled invalid on the theory

that "the duty of support is so important to the preser-

vation and stability of the marital relationship that

variation is against public policy and therefore void"

(Garlock v. Garlock, 1939).

There were some legal means through which third

parties would seek enforcement of support payments.

Under common law, while living with her husband, or

separated for good cause, the wife had the authority to

pledge his credit for the purchase of "necessaries" for

herself and the family (Clark, 1968).

This has been

described as the remedy afforded her if the husband

fails in his obligation of support (Ewell v. State,

1955).

This was actually a right available to the

creditor, not the wife.

She benefits only if she per-

22

suades the merchant to sell to her on the husband's

credit (Krauskopf and Thomas, 1974).

Poor laws or family responsibility statutes im-

posed an obligation upon certain persons to support

relatives.

In the tradition of Elizabethan poor laws,

these statutes were designed to secure minimum support

for the very poor.

They were not a remedy for enforce-

ment of the wife's common law right of support (Mandelker,

1956).

In essence, to attempt to obtain legal reinforce-

ment of the husband's duty to support, the wife had to

break up the family and seek a separation or divorce

decree.

If she chose to live with her husband, she

could, "in practice, get only what he chooses to give her"

(Citizens Advisory Council on the Status of Women, 1972).

In the United States, before and after The Married

Women's Property Acts were adopted, alimony could be

awarded upon absolute divorce even though the husband,

upon marriage, no longer acquired the property of his

wife.

Alimony awards have often been used to compen-

sate for the inequities of marital property law in

common law property states (Foster, 1978).

Such an

award "has always been inherently precarious.

It ceases

upon the death of the former husband and will cease or

falter upon his experiencing financial misfortune.

This

may result in serious misfortune to the wife and in some

cases will compel her to become a public charge"

23

(Rothman v. Rothman, 1974).

Under traditional divorce law, alimony was awarded

for the lifetime of either spouse or until remarriage

of the wife.

It was assumed that the wife had neither

the ability nor the resources to become self-supporting

(Foster, 1978). In 1979, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled

that wife-only statutes were based on sexual stereo-

types and were invalid, thus extending postdivorce

support to both partners (Orr v. Orr, 1979). As of

1984, forty-nine states have statutory provisions for

alimony, variously referred to as maintenance, allow-

ance, support, recovery, payment, separate maintenance,

and spousal support (Weitzman, 1981; Freed and Walker,

1985).

Alimony awards are still made through periodic

payments and are limited to the amount deemed "equitable

and just" (Karowe, 1974; Krause, 1981). The amount of

alimony awarded can be subject to modification or dis-

continuance upon a change in the earning capacity of

either spouse or other factors (Larson, 1979).

With the mounting dissolution rate, the advent of

no-fault dissolution, and the recent influx of women

into the labor force, the focal point of a spousal

support determination has shifted to the individual's

ability to become financially independent (Veith, 1978).

Advocates of divorce law reforms argue that the old laws

had converted "a host of physically and mentally compe-

tent young women into an army of alimony drones who...

24

become a drain on society and a menace to themselves"

(Doyle v. Doyle, 1957).

The aim of the new standards for alimony awards is

to provide support for spouses who (temporarily or

permanently) have compelling financial need (Weitzman

and Dixon, 1980; 1983).

This change has given rise to

the concept of rehabilitative alimony, also called

limited alimony or step-down spousal support.

Rehabil-

itative spousal support may be awarded for a period of

time during which the dependent spouse, usually the

wife, retrains for the job market.

This interim support

terminates automatically upon a date fixed in the final

decree of dissolution (Veith, 1978).

It should not be assumed that, historically, all

deserving wives received alimony (Foster, 1978).

In

fact, only a small percentage asked for or were awarded

alimony (Foster, 1978).

The U.S. Bureau of Census

reports that from 1822 to 1922, only 9 to 15 percent of

all divorces included provisions for alimony (Weitzman

and Dixon, 1980).

Today, alimony is awarded in less

than one-quarter of all divorces.

The national Commis-

sion on the Observance of International Women's Year

(1975) found that 14 percent of divorced wives surveyed

in a national poll said they were awarded alimony.

The

U.S. Bureau of the Census says that 15 percent of all

divorced or currently separated women in 1982 were

awarded alimony or maintenance payments or had an agree-

25

ment to receive them (Child Support and Alimony, 1983).

The amount of alimony typically awarded is too meager

to provide much economic protection for a dependent

spouse (Weitzman, 1981). In a random sample of 1977 Los

Angeles divorce decrees, Weitzman and Dixon (1980) found

the median alimony award was $209 per month.

The U.S.

Bureau of the Census reported that the mean total amount

of alimony received by women in 1981 was $3000 per year.

"After adjusting for inflation, this reflected a decrease

of about 25 percent from the 1978 level" (Child Support

and Alimony, 1983).

In order to determine whether awards had kept up

with the rate of inflation, Weitzman and Dixon (1980)

calculated the purchasing power of 1968 awards in 1977

dollars and vice versa, using the Consumer Price Index.

In Los Angeles, awards represented a real increase of

about $39 per month over the rate of inflation. Awards

in San Francisco, in contrast, had not kept up with the

rate of inflation.

Nonpayment of alimony and support obligations is

a widespread problem (Foster, 1978). Approximately 57

percent of alimony orders are violated (Child Support

and Alimony, 1983). Either no payment is made at all,

or payments are not made on time and arrearages build

up.

Even when payments are made for the first year or

two, they often stop or tail off with the passage of

time (Eckhardt, 1968; Foster, 1978). There is no other

26

area of law where court orders are so consistently vio-

lated (Foster, 1978).

Child Custody and Child Support

Initially in this country, child custody decisions

tended to follow English common law in that they con-

sidered the father to have the superior right to the

custody of his children, "and to the value of their

labor and services" (Derdeyn, 1976; Foster and Freed,

1978).

By the middle of the nineteenth century, there

was a gradual development of the belief that a child of

"tender years" required the care of the mother, and that

the child's best interests were served by awarding cus-

tody to the mother.

In the twentieth century, courts

are giving a substantial preference to the mother

(Mnookin, 1975).

This preference for maternal custody

was linked to the inclination of courts to award cus-

tody to the innocent party in a divorce action (Derdeyn,

1976; 1978).

Given the social convention that the wife

filed for divorce, the mother came to be the preferred

custodian (Foster and Freed, 1978; Mnookin, 1975).

The maternal preference standard was rarely ques-

tioned until the 1970's.

Social scientists began sug-

gesting that the legal standards of the time gave too

little weight to the psychological well-being of the

child and they called for "generally applicable guide-

lines" to govern all "child-placement disputes"

27

(Goldstein, Freud and Solnit, 1973).

This view has con-

tributed to recent legislative efforts toward sex-

neutral child custody statutes.

There is also a growing national trend toward

parents exercising joint custody of their children

(Folberg and Graham, 1979; Schulman and Pitt, 1982).

As of 1985, about 30 states had joint custody laws

which vary in substance and detail (Freed and Walker,

1985). Another recent phenomenon has been the enact-

ment of statutes in a growing number of states (in-

cluding Oregon) conferring upon a child's grandparents

legal standing to seek visitation rights with their

grandchildren after the divorce of the child's parents

(Freed and Foster, 1983).

A number of states have also

enacted laws criminalizing parental child abduction or

have put new teeth into their existing laws regarding

parental child abduction (Freed and Foster, 1984).

Today, in the majority of states, statutes impose

the obligation of child support on both parents (Freed

and Walker, 1985). Nevertheless, most courts continue

to place the major responsibility for postdivorce

support on the father (Derdeyn, 1978; Mnookin, 1981;

Weitzman, 1981). However, the amount of child support

payments is frequently small and many mothers receive

nothing at all (Espenshade, 1979). Yee (1979) reported

that child support orders entered by the Denver Dis-

trict Court during 1977-78 averaged $47.15 per month.

28

In a study conducted in 1972, Weitzman and Dixon (1979)

found that the median amount of child support ordered

for each child was $75 per month in Los Angeles. The

median total amount of child support per month per

family (for all children) was $121.

When these data

were compared to the estimated cost of raising two child-

ren to age 18 (Bureau of Labor Consumer Expenditure

Survey, 1960-61), the average child support awarded was

one-half of the direct cost of raising children in a

low-income family. Using data from a second sample,

drawn in 1977, they found that the median child support

award per child had risen to $100 per month and the

median total award had risen to $150. These amounts

had not kept up with the interim cost of living calcu-

lated at an increase of 8 percent per year. Nor were

they equal to half of the actual cost of raising a

child, even in a low-income family.

A 1972 report of

the Citizens Advisory Council on the Status of Women

concluded that "the data available indicate that pay-

ments generally are less than enough to furnish half of

the support of children," and that in most cases, ...

the mother is actually fulfilling a coextensive duty of

support to the child."

In California less than 10 percent of the child

support awards were tied to potential increases in the

father's income or to cost of living increases (Weitzman

and Dixon, 1979).

When the amount of child support re-

29

mains fixed, the payments are gradually consumed by in-

flation, and with each passing year, the mother assumes

an even greater share of the financial responsibility

for the children (Eden, 1979).

A large number of children never receive child

support awards in the first place. In a 1973 survey of

families receiving Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), ap-

proximately one-quarter of the mothers had child support

awards (Jones; Gordon, and Sawhill, 1976). In a 1975

survey of American women only 44 percent of the divorced

or separated mothers reported that they had been awarded

child support (National Commission on the Observance of

International Women's Year, 1975). In 1981, the Bureau

of the Census reported that of the 8.4 million families

with absent fathers, only five million were awarded

child support (Child Support and Alimony, 1983).

Many fathers are reluctant to live up to their

court-ordered support obligations (Collins, 1983;

Espenshade, 1979; Foster, 1978; Weitzman and Dixon,

1979). The first complete study of compliance with

child support orders was conducted by Professor Kenneth

Eckhardt in Wisconsin. Eckhardt (1968) found that in

the first year after the court order, 62 percent of the

fathers failed to comply fully with the order. Forty-

two percent did not make a single child support payment.

By the time ten years had passed, 79 percent of all

fathers had ceased providing any money. The Census

30

Bureau put the number of delinquents at over 2 million in

1981, 380,000 more than in 1978 (Child Support and Ali-

mony, 1983).

Recent years have brought new legislation aimed at

improving child support enforcement programs. The Uni-

form Reciprocal Enforcement of Support Act (URESA), ini-

tiated in 1950, permits the custodial parent to secure

support from the noncustodial parent residing in another

jurisdiction (Adams, 1983). Public law 93-647, passed

in 1975, established a federal parent locator service

to assist states in locating absent, non-supporting par-

ents (Uhr, 1979). And on August 16, 1984, Congress ex-

tended federal services to help enforce support in non-

welfare cases (Freed and Walker, 1985).

Typically, courts are lax in enforcing child sup-

port obligations (Collins, 1983; Espenshade, 1979).

There seems to be a general belief that a noncomplying

father simply does not have the means to support two

families.

In some cases a father's ability to support is

stretched to the limit by his remarriage and assumption

of the financial burdens of a new family. In other

cases, the husband's income is simply too low to share;

nothing divided by two is still nothing. Even husbands

who earn the average wage ... do not seem well off

enough to do without a large proportion of their income:

(Bane, 1976).

31

But Griffiths (1974), reporting to the U.S. House

of Representatives stated:

"We found no clear or consistent rela-

tionship between compliance with support

orders and absent parent's income.

Eighty-

two percent of the parents earning less

than $6,000 were not substantially complying

with their support orders or agreements- -

but neither were 66 percent of those earning

between $6,000 and $12,000, or 70 percent of

those earning $12,000 or more."

Winston and Forsher (1971), found that many

affluent fathers had evaded child support obligations

and that a number of physicians and lawyers had fam-

ilies who were ultimately forced onto welfare because

of the breakdown in enforcement of child support

orders.

They concluded that much middle-class poverty

is attributable to nonsupport by fathers who clearly

have the financial ability to comply with court orders.

And after a study of one small sample, Cassety

(1978) stated that an overwhelming majority of absent

fathers (86 percent) were "better off than their former

wives and children and even for many of the officially

poor mothers in the sample, enough money was available

to raise them above the poverty level without causing

the fathers to either fall below the poverty line or

to reduce their income level below that of their fam-

ilies."

She found only a small minority of the fathers

were truly unable to contribute anything toward the

support of their children while most could contribute

much more than the courts had believed possible.

She

32

concluded that "there appears to be an enormous untapped

source of funds that could be used to improve the eco-

nomic status of children in female-headed households."

Oregon Law

In 1971, Oregon became the second state to abolish

fault as the basis for dissolution of marriage and as a

basis for the award of spousal support and for the de-

termination of property settlements (Leo, 1972).

The

enactment of no-fault dissolution legislation was

hailed as a "realistic and generally rational approach

to an area of serious legal and social importance" (Leo,

1972).

Under earlier Oregon law, courts were required by

statute to make a disposition of real and personal prop-

erty as the courts deemed "just and proper in all cir-

cumstances" (Siebert v. Siebert, 1948).

Evidence of

fault, however, remained relevant to what constituted a

"just and proper" division of property (McCraw v. McCraw,

1962; Morgan v. Morgan, 1973).

"As this court has repeatedly and con-

sistently held in making a distribution of the

property of the marital community upon the

dissolution of a marriage, each case rests on

its own facts.

No formula can be stated, nor

percentage given, for all cases.

Each case

must be viewed independently, for a distribu-

tion which is just and proper in one case may

not be just and proper in another" (Johnson

v. Johnson, 1966).

This statute remained unchanged under Oregon's

33

Marriage Annulment and Dissolution Act of 1971, but evi-

dence of misconduct was no longer admissible.

Cases

decided under the 1971 act followed the property divi-

sion guidelines set out in Siebert v. Siebert (1948).

In Glatt v. Glatt (1979), the Oregon Court of

Appeals reaffirmed Siebert (1948) and stated, "the fac-

tors (that) ORS 107.105(1)(c) mentions with respect to

spousal support determination, while not controlling,

provide useful guidance in property divisions."

Those

factors were:

"(A) The duration of the marriage;

"(B) The ages of the parties;

"(C) Their health and conditions;

"(D) Their work experience and earning

capacities;

"(E) Their financial conditions, resources,

and property rights;

IT *

"(H) Such other matters as the court

shall deem relevant."

The court did not include (F) The provisions of the

decree relating to custody of the minor children of the

parties; or (G) The ages, health, and dependency condi-

tions of the children of the parties of either of them

(ORS 107.105 (1)(c)(A)-(H) (1974). Three years later,

the court said that "In practice, the financial portions

of a dissolution decree (spousal support, division of

property, and child support) are worked out together,

and none can be considered in isolation" (Grove v. Grove,

1977).

In 1977, the Oregon Legislative Assembly took

34

another step toward reform of the state's separate prop-

erty system in declaring that the contributions of home-

makers should be granted legal recognition in dividing

property and determining support awards (ORS 107.105(f)).

Under the 1971 Act, spousal support could be award-

ed to a party regardless of fault. The Act also delin-

iated factors for determining the amount and duration

of support: duration of the marriage, ages of the par-

ties, their health, their work experience and earning

capacities, their financial resources, the property and

custodial provisions of the decree, and the ages, health,

and dependency conditions of the minor children. The

trial court also retained discretion to considar addi-

tional factors which the court may deem relevant (ORS

107.105(1)(c); Stevenson, 1976).

In Grove v. Grove (1977), the Supreme Court dis-

cussed extensively the general questions surrounding

the award of spousal support. The court in Grove ac-

knowledged the interrelationship of spousal support,

property division, and child support (Stevenson, 1976).

On the question of duration of spousal support, the

court approved the general approach taken by the court

of appeals in Kitson v. Kitson (1974). To wit, when

there is a significant discrepency between a spouse's

probable future income and an income which would main-

tain the standard of living enjoyed during the marriage,

permanent spousal support is usually awarded (Grove v.

35

Grove, 1971). The court concluded that "the most sig-

nificant factor (in awarding support) is usually wheth-

er the wife's property and potential income, including

what she can earn or can become capable of earning will

provide her with a standard of living which is not

overly disproportionate to the one she enjoyed during

the marriage" (Grove v. Grove, 1977).

The court empha-

sized that it is not a comparison with the minimum

amount necessary to provide food, shelter, and other

basic necessities (Aarnas, 1978; Grove v. Grove, 1977).

ORS 107.105 was amended by the 1977 Legislative

Assembly to include two new factors for a court to con-

sider in awarding support.

"The need for maintenance,

retraining or education to enable the spouse to become

employable at suitable work or to enable the spouse to

pursue career objectives" and recognition of the home-

maker spouse "as an economic contributor to the marriage"

(ORS 107.105(1)(c)(H); ORS 107.105(1)(e), 1977).

The

1983 Legislative Assembly added several more factors to

be considered in awarding spousal support including the

contribution by one spouse to the education and earning

power of the other, the length of absence from the job

market by the dependent spouse and a realistic appraisal

of suitable job opportunities, the net spendable income

of the parties after assessing tax liabilities or bene-

fits, the costs of health care and life insurance premi-

ums, and the standard of living established during the

36

marriage (ORS 107.105(1)(d)(C)(F)(H)(J)(K)(L), 1983).

These changes also codified the Grove decision by in-

corporating the "not overly disproportionate to that

enjoyed during the marriage" standard (ORS 107.105 (1)

(d)(E)(M)).

In 1968, Tingen v. Tingen established factors to

be weighed in determining child custody, and held that

a party's misconduct is relevant only when it directly

affects the child's welfare (Tingen v. Tingen, 1968).

The 1971 Act eliminated the maternal preference statute

(Stevenson, 1976).

In Oregon, the court's primary con-

cern now is the "best interests of the child," with all

other matters being of secondary importance (In re Gaub,

1976; Ray v. Ray, 1972).

In 1981, Oregon's Supreme

Court rejected the use of tables or percentage methods

which were based on the noncustodial parent's income

alone as the appropriate means for determining the

amount of child support (O'Donnell, 1982).

By adopting

a "formula method," the court gave a clear directive

that both parents' incomes must be considered in deter-

mining the amount of support to be paid by the noncus-

todial parent (Smith v. Smith, 1981).

The formula re-

lating incomes of both parents to the child's needs

looks like this:

obligation of N =

income of N x needs of

income of N + income of C

children

where "N" represents the noncustodial parent and "C"

37

represents the custodial parent.

Criticism of the Smith

decision centered on the court's lack of guidelines in

determining the needs of the child leaving the trial

court to "decide whether ballet lessons, designer jeans

...or even the child's own room, are 'needs'"

(Allen,

1982; Smith, 1982).

Since 1977, bills have been introduced in every

biennial session of the Legislature proposing changes

in Oregon's divorce laws.

Many of these bills have been

spearheaded by the Women's Rights Coalition, which in-

cluded a dozen women's organizations, and the Oregon

Older Women's Caucus (Wohler, 1977).

In 1979, House

Bill 2648, a bill amending provisions relating to the

payment of child and spousal support and the division

of property, was defeated when the Coalition fell into

splinter factions in the face of heavy lobbying by a

divorced men's group (Williams, 1984).

Just before the

session ended, language mandating life insurance cover-

age on the obligor of child and spousal support was

written into another bill which did pass and became

Oregon law (ORS 107.820, 107.830).

The remaining sections of the bill were introduced

as House Bill 3177 in 1981.

Among its details were con-

siderations to be used in determining visitation rights,

the amount of child support, the support granted an ex-

spouse and additional grounds for

modifying a support

order should the obligor die prior to termination of the

38

support obligation (Turnquist, 1983). House Bill 3177

did not pass in 1981, but became the subject of an in-

terim study by the House and Senate Judiciary Committee,

clearing the way for final passage by the 1983 Legisla-

ture. As Senate Bill 12, the bill passed the Senate

almost unanimously and cleared the House with only ten

dissenting votes.

Governor Victor Atiyeh vetoed the

sections dealing with mandated joint custody, which had

been incorporated into the bill, and then signed Senate

Bill 12A-Engrossed into law on August 4, 1983 (ORS 107.

085, 107.105, 107.135, 107.407, 107.445, 107.820, and

ORCP 68C).

In 1985, the Legislative Assembly produced nearly

two dozen bills dealing with divorce issues: property

division, spousal support, child support, and child cus-

tody. The lobbying efforts of a fledgling political ac-

tion group called Dads Against Discrimination (DAD'S-

PAC) were aimed at creating a presumption favoring joint

custody (Hortsch, 1985).

It is not enough, in their

opinion, that state statutes or court decisions already

"encourage" joint custody, do award custody to some

fathers, and provide that neither parent shall have an

uncontested right to exclusive custody. Similar statutes

in other states have been vetoed on the grounds that

such statutes put the interests of the separating

spouses ahead of the best interests of the child (Freed

and Foster, 1983).

39

The Economics of Female-Headed Households

Between 1960 and 1982, there was a phenomenal

increase in the number of American families in which

only one parent, usually the mother, had the main

economic and social responsibility. The accelerated

growth in the number of one-parent families during

the 1970's--an increase of over 2.5 million--was far

greater than that of the preceding two decades.

The increasing prevalence of one-parent families

can be measured in terms of the proportion of children

living with only one parent (Ritagawa, 1981). Even

though the total number of children under 18 years old

in the United States declined by six million from 1970

to 1981, the number of children living with only one

parent rose by four million.

Thus, in 1980, one out of

every five children lived in a one-parent family

(Marital Status and Living Arrangements, 1983).

The

most prominent reason for the dramatic increase in the

number of one-parent families was the rising incidence

of divorce (Johnson, 1980; Ross and Sawhill 1975).

Accompanying the large increase in the number of

mothers maintaining their own families has been a

decline in the average age of female householders and

an increase in the number of families maintained by

women which contain young children. In 1979 there were

one million families with children under age six

maintained by women, and an additional 861,000 families

40

which had children under age six as well as children

ages six to 17 (Families Maintained by Female House-

holders, 1980).

One-parent families headed by women are more likely

than families maintained by men to be living at or

below the poverty level (Johnson, 1978; McEaddy, 1976;

Johnson, 1980).

Between 1965 and 1981, the number of

female - headed families living in poverty increased 70

percent while the number of all other poor families de-

clined 25 percent (Money Income and Poverty Status of

Families, 1982).

In 1981, the National Advisory Coun-

cil on Economic Opportunity said, "All other things

being equal, if the proportion of the poor who are in

female-headed families were to increase at the same

rate as it did from 1967 to 1978, they would comprise

100 percent of the poverty population by about the year

2000" (Caudle, 1982).

A number of explanations have been given why women

with children but without husbands find themselves in

such desperate economic straits: loss of economies of

scale; greater prevalence of divorce and death among

poor families; low and irregular levels of alimony,

child support and public assistance; fewer adult earn-

ers; fewer opportunities for female heads of families

to work; and lower wages than men when they do work

(Bane, 1976).

41

Loss of Economies of Scale

One economic fact of life is that it takes more

money to support two separate households than to sup-

port one household with the same number of people

(Vickery, 1978).

Economies of scale exist in rent,

furnishings, transportation, and food so that when

family members live together, the per capita cost of

maintaining a given level of living is less than when

living apart (Bane, 1976; Espenshade, 1979; Vickery,

1978).

When couples divorce these economic benefits

are reduced.

Emberson (1981), using revised data from

the U.S. Bureau of Labor, concluded that a four person

family consisting of husband, wife, and two children

would experience a 13 percent reduction in their level

of living if the parents divorced and set up separate

households.

Bane (1976) reported that "the loss of economies

of scale would in itself cause the proportion of child-

ren below the poverty level in female-headed families

to be approximately double that in male-headed families.

But in fact the proportion is six times greater, a much

larger difference than would be expected by economies

of scale alone."

Poverty as a Result of Divorce

Much of the decline in economic status experienced

by divorced mothers can be traced to the divorce (Bane,

42

1976; Brandwein, Brown and Fox, 1974). Kriesberg (1970),

in his study of mothers in poverty stated that "among

mothers who are husbandless due to separation or

divorce, whether or not they are poor is not related

to their socioeconomic status."

He indicated that in

addition to the poverty of many mothers prior to divorce,

a large number of previously non-poor wives and families

suffer downward economic mobility following divorce.

Using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics

(PSID), Hoffman (1977) compared the incomes of men and

women who stayed in intact families with the incomes of

men and women who were married in 1968 but divorced or

separated in 1974. Alimony and/or child support orders

were subtracted from the husband's income and added to

the wife's postdivorce income.

All income was calcu-

lated in constant 1968 dollars to examine changes in

real income. There was a sharp contrast in the economic

well-being of both men and women who were divorced by

1974. Divorced men lost 19 percent in real income while

divorced women lost 29 percent. Married men and women

experienced a 22 percent rise in real income during the

same period. To see what the income loss meant in terms

of family purchasing power, Hoffman and Holmes (1976)

constructed an index of family income in relation to

family needs. They found over the seven-year period

that the economic position of divorced men, when assess-

ed in terms of need, improved by 17 percent.

Over the

43

same period, divorced women experienced a seven percent

decline in terms of what their income could provide in

relation to their needs.

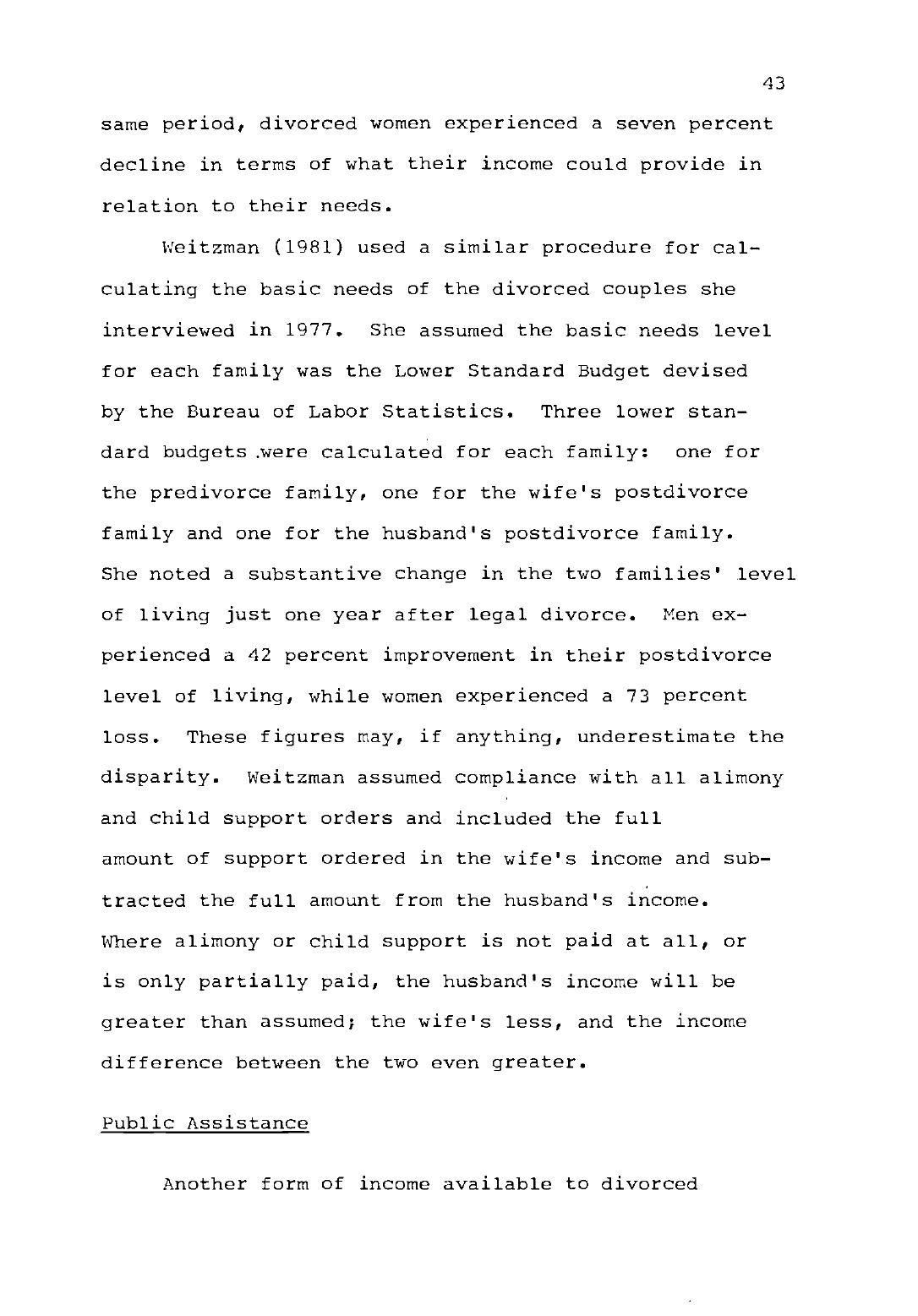

Weitzman (1981) used a similar procedure for cal-

culating the basic needs of the divorced couples she

interviewed in 1977. She assumed the basic needs level

for each family was the Lower Standard Budget devised

by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Three lower stan-

dard budgets .were calculated for each family: one for