Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M University School of Law

Texas A&M Law Scholarship Texas A&M Law Scholarship

Faculty Scholarship

11-2020

Facilitating Money Judgment Enforcement Between Canada and Facilitating Money Judgment Enforcement Between Canada and

the United States the United States

Paul George

Texas A&M University School of Law

, pgeorge@law.tamu.edu

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar

Part of the International Trade Law Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, and the Transnational Law

Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Paul George,

Facilitating Money Judgment Enforcement Between Canada and the United States

, 72

Hastings L.J. 99 (2020).

Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1442

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more

information, please contact aretteen@law.tamu.edu.

[99]

Facilitating Money Judgment Enforcement

Between Canada and the United States

JAMES P. GEORGE

†

The United States has attempted for years to create a more efficient enforcement regime for

foreign-country judgments, both by treaty and statute. Long negotiations succeeded in July 2019,

when the Hague Conference on Private International Law (with U.S. participants, including the

Uniform Law Commission) promulgated the new Hague Judgments Convention which

harmonizes judgment recognition standards but leaves the domestication process to the enforcing

jurisdiction. In August 2019, the Uniform Law Commission took a significant step to fill that gap,

though limited to Canadian judgments. The Uniform Registration of Canadian Money Judgments

Act provides a registration process similar to that for sister-state judgments in the United States.

The new Act aligns with Canada’s Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act, retaining

due process safeguards while facilitating acceptance of appropriate judgments. In most cases,

this will avoid the need for further litigation and lead to more efficient enforcement in adopting

jurisdictions. This Article outlines the new Act and then tackles difficult questions that remain

subject to local law.

†

Professor of Law, Texas A&M University School of Law. The Author thanks Committee Chair Lisa

Jacobs and National Conference Reporter Kathy Patchell, and each member of the drafting committee for their

excellent dialogue and result with the Act. The Author also thanks Kaitlin Wolff and other staff members at the

Uniform Law Commission, Texas A&M Reference Librarian Cynthia Burress, and administrative assistant

Andrea Hudson, all of whom contributed significantly to the Act and this Article. The conclusions, opinions,

and any errors are mine and not those of the Uniform Law Commission, the drafting committee, or the people

thanked here.

100 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 103

I. FOREIGN-COUNTRY JUDGMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA.... 104

A. THE UNITED STATES ...................................................................... 104

1. The Common Law ................................................................... 104

2. The Uniform Acts .................................................................... 106

3. Proposals for a National Standard—Treaty or Unilateral

Statute .................................................................................... 108

B. CANADIAN APPROACHES TO FOREIGN-COUNTRY JUDGMENTS ..... 109

1. Common Law .......................................................................... 109

2. The Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act (REJA-C) ..... 110

3. The Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act

(UEFJA-C) ............................................................................ 112

C. THE CANADIAN-U.S. PROJECT TO EXPEDITE CIVIL MONEY

JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT .......................................................... 113

II. THE UNIFORM REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN JUDGMENTS ACT................ 114

A. THREE ACTS COMPARED ............................................................... 114

B. A DRY RUN THROUGH REGISTERING AND OBJECTING .................. 119

1. Filing ...................................................................................... 120

a. Compliance ....................................................................... 120

b. Who May File ................................................................... 120

c. No Chain Recognition ....................................................... 120

d. What to Seek ..................................................................... 121

e. Limitations ........................................................................ 121

f. Alternate Procedures ......................................................... 121

2. Notice ...................................................................................... 121

a. Manner of Service............................................................. 122

b. Content ............................................................................. 122

3. The Thirty-Day Grace Period and Provisional Remedies ..... 122

4. The Judgment Debtor’s Defenses ........................................... 123

a. The Petition to Vacate Registration .................................. 123

b. Defenses to Registration ................................................... 123

c. Do Not Lie ........................................................................ 124

d. Stays.................................................................................. 124

e. Offsets or Counterclaims .................................................. 125

f. Relitigating the Merits ....................................................... 125

g. Reciprocity ........................................................................ 126

5. Costs and Attorney Fees ......................................................... 126

6. Appeals ................................................................................... 127

7. Enforcing the Domesticated Judgment ................................... 127

8. Relation to the 2005 Act ......................................................... 127

C. DEFERRAL TO THE ENFORCING STATE’S LAW ............................... 128

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 101

III. THE LARGER JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT SETTING UNDER THE

2005 ACT ............................................................................................. 129

A. SCOPE OR APPLICABILITY .............................................................. 130

B. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ............................................................. 131

1. The Rendering Forum ............................................................. 131

a. Personal Jurisdiction—Amenability and Notice............... 131

(1) Amenability ............................................................ 132

(2) Notice of the Rendering Forum’s Action ............... 136

(3) Default Judgment in the Rendering

Jurisdiction ............................................................. 137

b. Subject Matter Jurisdiction .............................................. 137

c. Venue ................................................................................ 138

2. The Enforcing Forum ............................................................. 138

a. Personal Jurisdiction........................................................ 138

(1) Amenability ............................................................ 138

(2) Notice in the Enforcing Forum .............................. 141

(3) Defaulting in the Enforcing Forum........................ 142

b. Subject Matter Jurisdiction in the Enforcing Forum ........ 142

c. Venue in the Enforcing Forum.......................................... 142

C. NON-JURISDICTIONAL CHALLENGES TO THE FOREIGN-COUNTRY

JUDGMENT ................................................................................... 143

1. Mandatory Grounds for Dismissal ......................................... 143

2. Discretionary Grounds for Dismissal ..................................... 144

D. GOVERNING LAW BEYOND PERSONAL JURISDICTION ................... 145

1. In the Rendering Court ........................................................... 146

2. In the Enforcing Court ............................................................. 146

a. Forum Clauses.................................................................. 146

b. Classifying the Foreign Judgment as Within the

2005 Act’s Scope ............................................................ 148

c. Finality in the Rendering Jurisdiction .............................. 150

d. Authentication or Certification of the

Foreign Judgment ........................................................... 150

e. What Assets Are Subject to Execution .............................. 150

f. Privity with the Judgment Debtor—Who Is Subject

to Execution?.................................................................. 152

g. Interest .............................................................................. 152

h. Evaluating Due Process, Fundamental Fairness, and

Impartiality..................................................................... 153

i. Superseding Law in the Enforcing Court: Federal and

International................................................................... 154

E. PARALLEL AND COLLATERAL LITIGATION ..................................... 156

CONCLUSION AND SPECULATIONS .................................................................. 158

102 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

IV. APPENDICES .............................................................................................. 161

A. THE UNIFORM FOREIGN-COUNTRY MONEY JUDGMENTS

RECOGNITION ACT (2005) ........................................................... 161

B. THE UNIFORM REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY

JUDGMENTS ACT (2019) .............................................................. 164

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 103

INTRODUCTION

In July 2019, the Uniform Law Commission approved an act that will

streamline the process to enforce a Canadian money judgment in the United

States. The Uniform Registration of Canadian Money Judgments Act (“2019

Registration Act”) supplements the Uniform Foreign-Country Money Judgment

Recognition Act (“2005 Act”) currently adopted in twenty-six states and

territories.

1

Under the 2005 Act, a party must file a lawsuit in order to seek

recognition for a foreign judgment, and if granted, it may enforce the foreign

judgment in the same manner as a judgment rendered locally. The 2019

Registration Act creates a registration procedure for use with Canadian money

judgments which does not require the party seeking recognition to file a lawsuit.

This Article explains the 2019 Registration Act and its relation both to its parent

Act and to the Canadian counterpart, the Canadian Uniform Enforcement of

Foreign Judgments Act.

This Article deals intricately with those three statutes and incidentally with

several others, all of which are popularly referred to with acronyms such as

UFCMJRA. Because of the acronyms’ similarity and the likelihood of

confusion, I will use shortened forms. There are three United States-based acts,

all aimed at state adoption:

• “the 1962 Act” is the Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act

• “the 2005 Act” is the Uniform Foreign-Country Money Judgments

Recognition Act

• “the 2019 Registration Act” is the Uniform Registration of Canadian

Money Judgments Act

There are two Canadian acts, adopted in various Canadian provinces and

territories:

• “the REJA-C” is the Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act

• “the UEFJA-C” is the Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act

Part I discusses the history of these acts.

In addition, readers must distinguish between a judgment’s recognition (the

enforcing state’s acceptance of a foreign judgment for preclusion or enforcement

purposes) and the judgment’s enforcement (execution against local assets). In

turn, recognition breaks down into recognition standards (such as the judgment

debtor’s amenability to the rendering state’s jurisdiction) and the initial

application process in the enforcing state (litigation versus registration). Part II

discusses the application process—registration—offered by the 2019

Registration Act.

Part III discusses the myriad of conflicting issues encountered following

judgment registration under the 2019 Registration Act or filing under the 2005

Act. Although judgment execution per se is beyond these Acts’ scope, it is

1

. For a list of enacting jurisdictions, see 2005 Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act, UNIF.

L. COMM’N, https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=ae280c30-094a-

4d8f-b722-8dcd614a8f3e (last visited Nov. 23, 2020).

104 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

important that attorneys and courts understand both the distinction and interplay

of the judgment recognition and the ensuing enforcement process. Part IV

summarizes the 2019 Registration Act’s contribution and speculates as to the

viability of registration in other judgment enforcement regimes.

I. FOREIGN-COUNTRY JUDGMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA

A. THE UNITED STATES

1. The Common Law

As Joseph Story noted in the early nineteenth century, foreign judgment

recognition has been the subject of “no inconsiderable fluctuation” in the

common law.

2

In chronicling this fluctuation, Story first noted a frequent

distinction in England between judgments offered for enforcement and those

offered in defense. Judgments filed for enforcement were treated as prima facie

evidence of the claim subject to attack for various errors—that is, the claim was

often relitigated. But judgments offered in defense were analyzed under

preclusion principles.

3

Using that practice as a starting point, Story offered

several pages of variations ranging from moderations to sharp deviations from

the English view.

4

The United States at that point had insufficient legal history

to draw conclusions. Story reported only the generality that foreign judgments

were prima facie evidence but impeachable, and that “how far and to what extent

this doctrine is to be carried, does not seem to be definitely settled.”

5

The United States Supreme Court took a large step in 1895 to straighten

the fluctuation in its review of a French judgment. In Hilton v. Guyot,

6

the Court

explained at length that foreign-country judgments are entitled to recognition

under twin standards of comity and reciprocity. As to comity, the Court stated

we are satisfied that, where there has been opportunity for a full and fair trial

abroad before a court of competent jurisdiction, conducting the trial upon

regular proceedings, after due citation or voluntary appearance of the

defendant, and under a system of jurisprudence likely to secure an impartial

administration of justice between the citizens of its own country and those of

other countries, and there is nothing to show either prejudice in the court, or

in the system of laws under which it was sitting, or fraud in procuring the

judgment, or any other special reason why the comity of this nation should not

allow it full effect, the merits of the case should not, in an action brought in

2

. JOSEPH STORY, COMMENTARIES ON THE CONFLICT OF LAWS, FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC, IN REGARD TO

CONTRACTS, RIGHTS, AND REMEDIES, AND ESPECIALLY IN REGARD TO MARRIAGES, DIVORCES, WILLS,

SUCCESSIONS, AND JUDGMENTS § 603 (Lawbook Exch. 2d ed. 2001) (1841).

3

. See id. § 598.

4

. See id. §§ 598–610; see also Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113, 180–95 (1895).

5

. STORY, supra note 2, § 608; see also Smith v. Lewis, 3 Johns 157, 169 (N.Y. 1808) and other cases

and treatises discussed in PETER HAY, PATRICK J. BORCHERS, SYMEON C. SYMEONIDES, & CHRISTOPHER A.

WHYTOCK, CONFLICT OF LAWS 1421–22 (West Acad. Publ’g 6th ed. 2018).

6

. Hilton, 159 U.S. at 113.

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 105

this country upon the judgment, be tried afresh, as on a new trial or an appeal,

upon the mere assertion of the party that the judgment was erroneous in law

or in fact.

7

The Court—and on this second point a bare majority—held further that

comity required reciprocity, and because France did not give conclusive effect

to United States judgments, the Court would not recognize the French

judgment.

8

A strong four-justice dissent favored the French judgment, arguing

that preclusion was the common law mandate here rather than the more

politically oriented comity, and that reciprocity had no role in the analysis.

9

The

Hilton majority thus held that the question of foreign-country judgment

recognition was one of public law, conceivably addressable by a national or

international standard. The Hilton dissent argued for preclusion, a question of

the common law and thus private law. That question—public law or private

law—continues to be debated in regard to foreign country judgment recognition.

The next instance of that ongoing debate came from the New York Court

of Appeals in 1926. In Johnston v. Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, the

New York Court of Appeals rejected Hilton’s comity and reciprocity standard,

and instead followed the Hilton dissent by applying New York’s common law

of preclusion to the French judgment’s recognition.

10

Johnston’s holding made

two important points. First, the recognition of the French judgment was a

question of private law based on preclusion, and not public law based on comity.

Second, because it was a question of private law, it was a state law question

governed by New York law.

The state law view was bolstered in 1938 when the Supreme Court decided

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, holding that diversity cases were governed by

the law of the state in which the federal court sat.

11

Although Erie applied only

to federal courts (and not, for example, to state court actions on foreign-country

judgments), the doctrine came to stand for something much broader than the

governing law in diversity cases. For example, in Somportex Ltd. v. Philadelphia

Chewing Gum Corp.,

12

the Third Circuit Court of Appeals cited Erie in holding

that Pennsylvania law governed the recognition of an English default

judgment.

13

Interestingly, Pennsylvania’s applicable law was comity, based on

Hilton, but rejected Hilton’s reciprocity.

14

In any event, Erie clarified the

primacy of state common law even outside of federal litigation, including its

application to what the Hilton majority assumed was a question of public law

and national scope. To the extent the Hilton majority purported to announce a

federal standard for recognizing foreign-country judgments, the combination of

7

. Id. at 202–03.

8

. Id. at 210.

9

. Id. at 233–34.

10

. Johnston v. Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, 242 N.Y. 381, 386–88 (1926).

11

. Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, 80 (1938).

12

. Somportex Ltd. v. Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corp., 453 F.2d 435 (3d Cir. 1971), cert. denied, 405

U.S. 1017 (1972).

13

. Id. at 440.

14

. Id. at 440 & n.8.

106 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

Johnston and Erie has ended that. Nonetheless, state courts are free to adhere to

Hilton’s comity and reciprocity standard, and some do.

15

On the other hand, state

law’s current dominance of foreign-country judgment recognition does not mean

that federal law cannot control the question, but only that in the absence of

federal law—federal statute or treaty—state law controls.

2. The Uniform Acts

In 1948, the Uniform Law Commission approved the Uniform

Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act (US-UEFJA) to provide clearer

enforcement of sister-state judgments. Although the US-UEFJA was merely a

codification of the common law standard under full faith and credit, it expedited

sister-state judgment enforcement by requiring only a registration rather than a

new lawsuit. The sister-state Act had sufficient success

16

to encourage the

Uniform Law Commission to consider a similar act for foreign-country

judgments.

That happened in 1962 with the promulgation of the Uniform Foreign

Money Judgment Act (“1962 Act”). As the California Supreme Court noted,

“[t]he purpose of the uniform act was to codify the most prevalent common law

rules for recognizing foreign money judgments and thereby encourage the

reciprocal recognition of United States judgments in other countries.”

17

There

were, of course, a number of differences from the sister-state Act. Notably, first,

the sister-state Act applies to any judgment entitled to full faith and credit

18

but

the 1962 Act applies only to money judgments other than those for taxes, fines,

other penalties, or family law judgments.

19

Second, the 1962 Act does not allow

for mere registration of the foreign-country judgment but instead requires

“recognition” accomplished through a new lawsuit,

20

although the 1962 Act

itself did not make that clear.

21

Third, the 1962 Act allows for both preclusion

15

. See HAY ET AL., supra note 5, at 1424–25 & n.305.

16

. As of 2019, the Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act (U.S.) has been enacted in forty-eight

states (all but California and Vermont) plus the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands. 1964

Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act, UNIF. L. COMM’N, https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/

community-home?CommunityKey=e70884d0-db03-414d-b19a-f617bf3e25a3 (last visited Nov. 23, 2020).

17

. Manco Contracting Co. (W.L.L.) v. Bezdikian, 195 P.3d 604, 608 (Cal. 2008) (citing 13 pt. II West’s

U. Laws Ann. (2002) Unif. Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act, Prefatory Note, p. 40).

18

. See UNIF. ENF’T OF FOREIGN JUDGMENTS ACT § 1 (UNIF. L. COMM’N 1964).

19

. See UNIF. FOREIGN MONEY-JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT § 1(2) (UNIF. L. COMM’N 1962).

20

. For sister-state judgments, full faith and credit requires recognition when a qualified judgment is

registered. Because foreign-country judgments do not qualify for full faith and credit, a summary proceeding is

necessary.

21

. The drafters apparently believed that the need to file a new action in the enforcing state was obvious

since it was required under the common law. That oversight was one of the reasons for the revisions that came

in 2005 with the Uniform Foreign Country Money Judgment Recognition Act. See UNIF. FOREIGN-COUNTRY

MONEY JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT § 6 cmt. 1 (UNIF. L. CMM’N 2005). In the meantime, states had varying

reactions to the 1962 Act’s failure to specify a filing requirement. Florida saw it as acceptable to use a registration

procedure that the drafters did not intend. See FLA. STAT. ANN. § 55.604 (2019). No other state drafted a

registration procedure as such, but some courts interpreted it that way. See, e.g., Vrozos v. Sarantopoulos, 552

N.E.2d 1093, 1099–1101 (Ill. App. Ct. 1990); Maxwell Shuman & Co. v. Edwards, 663 S.E.2d 329, 331–32

(N.C. Ct. App. 2008). A Texas court, on the other hand, held the 1962 Act unconstitutional for its failure to

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 107

and enforcement.

22

Finally, the 1962 Act provides additional defenses and

protections for the judgment debtor.

23

The 1962 Act was eventually adopted by

thirty-five states and three territories,

24

but several have replaced it with the 2005

Act. As of 2019, ten states and one territory use the 1962 Act—Alaska,

Connecticut, Florida, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York,

Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the Virgin Islands.

25

The 1962 Act’s failure to provide an express procedure, along with other

perceived shortcomings, led to an updated Act in 2005. The changes from the

1962 Act are explained in the 2005 Act’s prefatory note and include clarifying

(in some cases enlarging) the definitions,

26

scope,

27

burdens of proof,

28

need to

file a legal action in the enforcing state,

29

defenses,

30

and the addition of a statute

of limitations.

31

The 2005 Act has been adopted in twenty-six U.S. jurisdictions:

Alabama, California, Colorado, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia,

Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada,

New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon,

Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Washington.

32

require notice to the judgment debtor. See Detamore v. Sullivan, 731 S.W.2d 122, 124 (Tex. Ct. App. 1987)

(denying writ of mandamus). As a result, the Texas legislature amended its version of the 1962 Act to specify a

notice requirement. See Don Docksteader Motors, Ltd. v. Patal Enterprises, Ltd., 794 S.W.2d 760, 761 (Tex.

1990).

22

. Whether the foreign-country judgment is presented for collection or preclusion, it first requires

recognition as a qualified judgment. For sister-state judgments, recognition is automatic so there is no need for

a summary proceeding when submitting it for preclusion, which will necessarily be in an existing action.

Enforcing the sister-state judgment, which usually means collecting a money judgment, requires registration

under the US-UEFJA in order to give notice to the judgment debtor and to open a domestic cause number. See

generally UNIF. FOREIGN MONEY JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT.

23

. In addition to the jurisdictional defenses under the sister-state act, the 1962 Act includes defenses such

as unfair legal system and public policy violations that are unavailable under the sister state act. See id. § 4.

24

. HAY ET AL., supra note 5, at 1425.

25

. See UNIF. FOREIGN MONEY JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT, U.L.A. Refs & Annos (2020). The

Uniform Laws Annotated reference table lists Delaware and Illinois, but those states also appear on the 2005

Act reference table and both show current versions of the 2005 Act.

26

. See UNIF. FOREIGN-COUNTRY MONEY JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT § 2 (refining the definitions to

read “foreign country” and “foreign-country judgment”).

27

. See id. § 3 (clarifying certain exclusions such as domestic relations judgments).

28

. The judgment creditor or other party seeking recognition bears the initial burden to establish that the

judgment falls within the Act’s scope. See id. § 3(c). Once that burden is met, the judgment is presumed

enforceable and the judgment debtor (or other party opposing recognition) bears the burden of establishing a

basis for nonrecognition. See id. § 4(d).

29

. See id. § 6.

30

. See id. §§ 4(c)(7)–(8) (adding discretionary nonrecognition grounds based on the rendering court’s

integrity and due process violations in foreign proceedings). The best explanation of defense distinctions

between the 1962 Act and the 2005 Act comes from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in DeJoria v. Maghreb

Petroleum Exploration, S.A., 804 F.3d 373, 386 (5th Cir. 2015) [hereinafter DeJoria I], rev’d, 935 F.3d 381 (5th

Cir. 2019) [hereinafter DeJoria II]. In DeJoria II, the judgment debtor successfully opposed a Moroccan

judgment by lobbying the Texas legislature to adopt the 2005 Act which added crucial defenses. DeJoria, 935

F.3d at 387–88.

31

. See UNIF. FOREIGN-COUNTRY MONEY JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT § 9.

32

. See 2005 Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act, supra note 1.

108 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

3. Proposals for a National Standard—Treaty or Unilateral Statute

As noted above, state law governance of foreign-country judgment

recognition is not a foregone conclusion. National standards have been

continuously proposed at least back to Hilton. The most notable effort, which

may now succeed in the United States, is through the Hague Conference on

Private International Law, which in 1993 began drafting a Convention on

Jurisdiction and the Recognition of Judgments. The process continued through

2001, but negotiations reached impasses on jurisdictional bases such as “tag

jurisdiction” and “general jurisdiction” (doing business in the forum unrelated

to the claim). When it became clear that no agreement was in sight, the

negotiators took a fallback position and crafted an agreement on forum clauses

that became the Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements.

33

During the Hague negotiations, the American Law Institute (ALI)

undertook the drafting of a federal statute designed to implement the anticipated

Hague Judgments Convention. The ALI work began in 1998,

34

and when the

Hague efforts failed, the ALI switched the plan to creating a federal statute that

would create a federal standard for recognizing foreign-country judgments.

Controversies during that process included some ALI members’ resistance to a

federal standard, and other members’ preference for a reciprocity requirement.

35

That work was completed in 2005 with a proposed federal statute that included

reciprocity,

36

but it did not reach Congress.

Treaty proponents did not give up, and in 2019 the Hague Conference

finalized the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign

Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters.

37

The Convention states the

standards for recognition including jurisdiction, defenses, and authentication,

38

but leaves the filing or registration procedure, along with enforcement, up to the

enforcing state’s law.

39

Additionally, the Convention expressly retains the

enforcing states’ existing recognition and enforcement methods.

40

The

Convention opened for signing on July 2, 2019, but as of this writing only

Uruguay has signed.

41

Ratification in the United States is of course speculative,

33

. See Convention on Choice of Court Agreements, 44 I.L.M. 1294 (2005), https://assets.hcch.net/

docs/510bc238-7318-47ed-9ed5-e0972510d98b.pdf. The United States has signed but not ratified the

convention. See Status Table, HAGUE CONF. ON PRIVATE INT’L L., https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/

conventions/status-table/?cid=98 (last visited Nov. 23, 2020).

34

. See Memorandum from Professor Andreas F. Lowenfeld & Professor Linda Silberman to the Council

of the Am. L. Inst. (Nov. 30, 1998), https://www.ali.org/media/filer_public/ed/f9/edf92d0f-e280-4480-b8de-

5aade127c56c/foreign-judgments-memorandum.pdf.

35

. See Lance Liebman, Foreword to AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE, RECOGNITION AND ENFORCEMENT OF

FOREIGN JUDGMENTS: ANALYSIS AND PROPOSED FEDERAL STATUTE, at xii–xiii (2005).

36

. See id. at xi–xii.

37

. See Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial

Matters, July 2, 2019, https://assets.hcch.net/docs/806e290e-bbd8-413d-b15e-8e3e1bf1496d.pdf.

38

. See id. at art. 5 (jurisdictional bases), art. 6 (in rem exclusion), art. 7 (defenses), art. 12 (authentication).

39

. See id. at art. 13.

40

. See id. at art. 15.

41

. See Status Table, HAGUE CONF. ON PRIV. INT’L L., https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/

status-table/?cid=137 (last visited Nov. 23, 2020).

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 109

and if ratified, it is not clear what reservations might be imposed. Assuming it is

ratified in the United States and the implementing statute does not impose

additional requirements on enforcing states (that would create a federal

enforcement law), then the Convention appears to be compatible with both

current recognition and enforcement methods, including common law, the 1962

Act, the 2005 Act, and (if enacted by states) the 2019 Canadian Judgment

Registration Act.

B. CANADIAN APPROACHES TO FOREIGN-COUNTRY JUDGMENTS

This review of Canadian law is brief because this Article is about judgment

enforcement in the United States. The discussion here involves Canadian

jurisdictions only to the extent of harmonizing United States practice, at least in

the twenty-six states using the 2005 Act, and hopefully in newly-adopting states.

Interestingly, Canadian law on foreign-country judgment enforcement is more

complex than in the United States because Canada has not only the same internal

border issues, but has also managed to tie into specific treaties with the United

Kingdom

42

and France,

43

and has other federal legislation geared to judgment-

enforcement treaties.

44

A full summation of the larger Canadian law on foreign-

judgment enforcement would take several pages and is unnecessary in this

Article about a new act for adoption in the United States. The discussion below

is limited to Canada’s uniform provincial laws directed to foreign-country

judgment enforcement.

1. Common Law

Canada’s foreign-judgment enforcement system evolved from common

law enforcement which prevailed until statutory procedures emerged in the

twentieth century. As with the doctrinal struggle in the United States, Canadian

law on foreign-judgment enforcement vacillated between a preclusion-based

system and a sovereignty-based comity approach that included reciprocity. The

leading Canadian treatise on the subject explains the theoretical contrast between

the common law and typical civil law systems: common law enforcement tends

to be on a case-by-case basis, while many non-common law countries either do

42

. See Convention Between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Northern Ireland Providing for the Reciprocal Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in

Civil and Commercial Matters, Can.-U.K., Apr. 24, 1984, 1987 Can. T.S. No. 29 (enacted as the Canada-United

Kingdom Civil and Commercial Judgments Convention Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-30); see also JEAN-GABRIEL

CASTEL & JANET WALKER, CANADIAN CONFLICT OF LAWS § 14.27 (LexisNexis Can. Inc. 6th ed. 2005).

43

. See Convention Between the Government of Canada and the Government of the French Republic on

the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters and on Mutual Legal

Assistance in Maintenance, Can.-Fr., June 10, 1996, https://www.ulcc.ca/en/annual-meetings/377-1997-

whitehorse-yk/civil-section-documents/1132-convention-between-government-of-canada-and-government-of-

french-republic-1997?showall=1&limitstart=. For an example of adoption in a Canadian province, see The

Enforcement of Judgments Convention and Consequential Amendments Act, C.C.S.M. c E117 (Can. Man.). See

also CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.28.

44

. See CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.29 (discussing Canadian federal statutes directed to

foreign and international judgments regarding antitrust, foreign trade, oil pollution, and terrorism victims).

110 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

not recognize foreign judgments at all (requiring re-litigation) or recognize

judgments from specific reciprocating countries, subject to a few objections.

45

This resembles the contrasting views in the United States as shown in the Hilton

majority and dissent, and the Hilton dissent’s echo in Johnston.

46

Like jurisdictions in the United States, the results in Canada have been a

hybrid. The two Canadian statutory-enforcement systems—the REJA-C and the

UEFJA-C—are based on the common law but differ in their procedures, and

common law enforcement remains available as an alternative to registration or

recognition under one of the standardized Canadian acts.

47

2. The Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act (REJA-C)

Statutory procedures began to replace common law enforcement in the

early twentieth century. The REJA-C, though originally derived from a 1924

model law, is now a collection of statutes with varying content

48

used in most

Canadian provinces and territories—all but Quebec and Saskatchewan.

49

The

adopted versions are not uniform in sections, wording, or scope.

50

According to

Professor Janet Walker, the REJA-C was originally intended as a catch-all act

to provide a registration procedure for civil money judgments from reciprocating

jurisdictions—both Canadian and foreign.

51

This is consistent, for example, with

Alberta’s REJA-C.

52

The adopted versions in various provinces and territories have naturally

mutated over the many years, and now New Brunswick applies its REJA-C only

to foreign-country judgments,

53

using other statutes to enforce other Canadian

judgments. Ontario applies its REJA-C only to Canadian provinces and

territories,

54

presumably leaving judgment creditors from foreign countries to

use common law enforcement. There are, however, three common features

among all REJA-C versions: a convenient registration procedure, the option to

use common law recognition/enforcement, and a stiff reciprocity requirement.

45

. See id. § 14.1.

46

. See Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113, 180–95 (1895); Johnson v. Compagnie Generale Transatlantique,

242 N.Y. 381, 385 (1926).

47

. See generally CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, ch.14.

48

. See id. § 14.24 & n.1.

49

. Ten Canadian jurisdictions have enacted a version of the REJA-C, labeled as such: Reciprocal

Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.A. 2000, c R-6 (Can. Alta.); Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act,

R.S.M. 1987, c J20 (Can. Man.); Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.N.B. 2014, c 127 (Can. N.B.);

An Act to Facilitate the Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments, R.S.N. 1990, c R-4 (Can. Nfld.); Reciprocal

Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.N.W.T. 1988, c R-1 (Can. N.W.T., Nun.); An Act Respecting the Reciprocal

Enforcement of Judgments, R.S.N.S. 1989, c 388 (Can. N.S.); Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgements Act,

R.S.O. 1990, c R.5 (Can. Ont.); Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.P.E.I. 1988, c R-6 (Can. P.E.I.);

Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.Y. 2002, c 189 (Can. Yukon).

50

. As with uniform acts in the United States, various differences exist between the Canadian jurisdictions’

REJA-C adoptions. See CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.24.

51

. See id.

52

. See Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.A. 2000, c R-6, § 1 (Can. Alta.); Reciprocating

Jurisdictions Regulation, Alta. Reg. 344/1985, § 1 (Can. Alta.).

53

. See Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.N.B. 2014, c 127, §§ 1, 3 (Can. N.B.).

54

. See id. § 1; see also Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, Ont. Reg. 322/92, § 1 (Can. Ont.).

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 111

The REJA-C is an improvement over the common law with its option for

registering the foreign judgment instead of having to file a new action and

endure a summary proceeding.

55

The disadvantage is the element of reciprocity,

and not just the requirement, but the overlay of an administrative process. Under

the REJA-C, reciprocity is not a question to be determined ad hoc by the

enforcing court, but instead requires an administrative process in which the

province’s Lieutenant Governor declares the rendering jurisdiction to be a

reciprocating jurisdiction.

56

Once a U.S. state is designated on a province’s

reciprocating list, future judgment creditors can benefit, but the list of approved

U.S. states is small. Alberta, for example, has recognized only Arizona, Idaho,

Montana, and Washington as eligible reciprocating states.

57

The process of

having the rendering state placed on the reciprocating list is sufficiently difficult

that many judgment creditors choose the common law recognition, although

there is no available data to assess how many there are in each province. There

is evidence, though, of frustration with the process. Some judgment creditors

have tried to circumvent the reciprocity requirement by first filing in a

reciprocating province and then seeking intra-Canadian enforcement. The

REJA-C anticipates this and prohibits the practice. That is, the original rendering

court must be from a jurisdiction officially recognized as reciprocating.

58

One common feature in the various REJA-Cs is the option of foregoing

registration (and cumbersome reciprocity) and filing a new action. As with the

1962 Act and the 2005 Act in the United States, the new action is directed to the

foreign-country judgment rather than the underlying claim and anticipates

summary resolution based on preclusion.

59

Two Canadian jurisdictions have not adopted the REJA-C. Quebec—a civil

code jurisdiction—has drafted code provisions

60

based on the 1971 Hague

Judgments Convention.

61

The Quebec code does not impose reciprocity but also

has no registration option.

62

Saskatchewan has adopted the latest version of

Canada’s Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act, which offers a

registration procedure, lacks reciprocity, and is discussed immediately below.

55

. Professor Walker notes that the REJA-C registration process “is more efficient than the common law

method of enforcement but it can still be cumbersome and expensive.” CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42,

§ 14.24, at 14-103.

56

. See, e.g., Reciprocal Enforcement of Judgments Act, R.S.A. 2000, c R-6, § 8 (Can. Alta.); see also

CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.24 & nn.4–5. In contrast, states in the United States using reciprocity

treat it as a judicial question and some states make it discretionary. See, e.g., TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE

ANN. § 36A.004(c)(9) (2019).

57

. See Reciprocating Jurisdictions Regulation, Alta. Reg. 344/1985, § 1 (Can. Alta.).

58

. See CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.24 & n.5.

59

. See id. § 14.24 & n.3.

60

. See Civil Code of Québec, S.Q. 1991, c 64, arts. 3155–68 (Can.); Code of Civil Procedure, R.S.Q.

2014, c 1, arts. 507–08 (Can.).

61

. Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial

Matters, Feb. 1, 1971, 1144 U.N.T.S. 249, https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/full-text/?cid=78;

CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.13 & n.3. The 1971 Hague Judgments Convention (ratified only by

Albania, Cypress, Kuwait, the Netherlands, and Portugal), not to be confused with the 2019 Hague Judgments

Convention, just opened for signature.

62

. See CASTEL & WALKER, supra note 42, § 14.3 & n.51.

112 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

3. The Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act (UEFJA-C)

The Uniform Law Conference of Canada has long encouraged a

reciprocity-free procedure for foreign-country judgments. The original model

came out in 1933 with the Model Foreign Judgments Act, which has been

revised many times since.

63

The earliest versions dropped the reciprocity

requirement with its cumbersome administrative layer

64

but until recently the

UEFJA-C did not have a registration option like the REJA-C. The Uniform Law

Conference of Canada (ULC-C) produced the most recent version in 2003 and

Saskatchewan enacted it in 2005.

65

New Brunswick has enacted, in addition to

its REJA-C, what appears to be a prior version of the UEFJA-C entitled the

Foreign Judgments Act. The New Brunswick version does not require

reciprocity but lacks a registration procedure and instead requires a new action

on the foreign judgment,

66

which makes it simply a codification of the common

law similar to the 2005 Act in the United States.

The UEFJA-C is a well-structured Act that offers cost-and-time reduction

while retaining due process concerns. While the REJA-C applies (with some

exceptions) to judgments rendered outside the enforcing forum, including other

Canadian jurisdictions,

67

the UEFJA-C is limited to judgments from “foreign

States,” not referring to other Canadian provinces or territories.

68

A line-item

comparison with the REJA-C is not practical because the REJA-C lacks a current

model-law format and its ten adoptions vary significantly. A few general

comparisons are possible, though. Compared to the general format for the

various REJA-Cs, the UEFJA-C has more definitions,

69

a more tightly defined

scope with additional exclusions,

70

a different limitations rule,

71

a clearer default

judgment rule,

72

discretion to enforce non-monetary judgments,

73

an option for

partial enforcement if parts of the foreign judgment exceed the Act’s scope,

74

more defenses for the judgment debtor,

75

a more nuanced burden of proof,

76

precise judgment interest rules,

77

and a clearer rule for monetary conversion.

78

Like the REJA-C, the UEFJA-C is structured around a registration process, and

63

. See id. § 14.23 & n.1.

64

. Compare id. § 14.23, with id. § 14.24.

65

. The Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act, R.S.S. 2005, c E-9.121 (Sask. Can.).

66

. Although the New Brunswick Foreign Judgments Act does not expressly authorize an action on a

foreign judgment, its only function is to regulate such an action. See Foreign Judgments Act, R.S.N.B. 2011, c

162, §§ 5–6, 8 (N.B. Can.).

67

. See supra notes 51–52 and accompanying text.

68

. See Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act § 2 (Unif. L. Conf. Can. 2003) (Can.) (defining

“foreign judgment”).

69

. See id. § 2 (providing eight definitions).

70

. See id. § 3.

71

. See id. § 5.

72

. See id. §§ 4(d), 9.

73

. See id. § 7.

74

. See id. §§ 6, 12.

75

. See id. §§ 4, 10.

76

. See id. § 10.

77

. See id. § 15.

78

. See id. § 13.

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 113

unlike the REJA-C, the UEFJA-C not only abandons the cumbersome

administrative process regarding the reciprocity list with the Lieutenant

Governor, but abandons the reciprocity element entirely. The UEFJA-C is one

of this Article’s three focus acts and its details are outlined in the chart below.

79

C. THE CANADIAN-U.S. PROJECT TO EXPEDITE CIVIL MONEY JUDGMENT

ENFORCEMENT

Vibrant economies benefit from predictable and consistent judgment

enforcement regimes. This was true when the drafters included the full faith and

credit clause in the United States Constitution, and it remains true in the twenty-

first century. On the other hand, judgment enforcement is also a local matter

because of its in rem nature—an action against necessarily local assets. Those

local interests explain why foreign-country judgment enforcement resists

standardization. In a federalist system like the United States or even in more

traditional polities, local customs and policies evolve both judicially and

legislatively to accommodate those competing national and local interests.

Finding the balance between them is essential.

The only universally agreed-upon point in transnational judgment

enforcement is that the rendering forum must have jurisdiction over the

defendant/judgment debtor.

80

For interstate judgment enforcement in the United

States, the full faith and credit clause resolved recognition disparities and

compelled common law enforcement through summary actions. Building on

that, the Uniform Law Commission’s UEFJA increased sister-state enforcement

efficiency by replacing the summary legal action with a registration system.

81

Judgments from foreign countries are a different matter because of inherent

distrust of foreign legal systems. But arguments against greater efficiencies—

such as registration—fade for judgments from countries with similar legal

traditions. Canada and the United States are ideal matches, and at its January

2017 meeting, the Uniform Law Commission approved a joint project with the

Uniform Law Conference of Canada to draft an act harmonizing the 2005 Act

and the UEJFA-C.

82

The stated goal was a registration procedure for United

States jurisdictions that would match that in Canada and create a more efficient

79

. See infra Part II.A.

80

. See ANDREAS F. LOWENFELD, INTERNATIONAL LITIGATION AND ARBITRATION 471 (3d ed. 2005)

(citing, inter alia, ENFORCEMENT OF FOREIGN JUDGMENTS WORLDWIDE (C. Platto & W.G. Horton eds., 2d ed.

1993)). Even with United States jurisdictions using the 2005 Act, the approach varies. Although the 2005 Act

calls for the filing of a new legal action in the enforcing state, some states routinely allow registration. See, e.g.,

CE Design Ltd. v. HealthCraft Prods., Inc., 79 N.E.3d 325, 329–30 (Ill. App. Ct. 2017). In other states requiring

a recognition action, courts sometimes allow registration anyway. See, e.g., Hyundai Sec. Co. v. Lee, 155 Cal.

Rptr. 3d 678, 682–84 (Ct. App. 2013). Nonetheless, judgment registration has not taken hold with foreign-

country judgments.

81

. See, for example, TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE ANN. § 35.003 (2019), the Texas version of the 1964

Act. Cross border judgment recognition is controversial enough that even sister-state judgment enforcement was

not always efficient or consistent. See supra notes 4–5 and accompanying text.

82

. See Unif. L. Comm’n, Minutes: Midyear Meeting of the Executive Committee 7 (Jan. 14, 2017),

https://www.uniformlaws.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=2164ce2

7-3552-7548-25a2-457abf438c12.

114 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

domestication of civil money judgments between the two countries.

83

The joint

drafting committee had its first meeting in October 2017, and two years later

presented its proposed final act at the 2019 Annual Meeting in Anchorage,

Alaska. On July 17, 2019, the Uniform Law Commission approved the Uniform

Registration of Canadian Money Judgments Act and forwarded it to the states

for enactment.

84

II. THE UNIFORM REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN JUDGMENTS ACT

The 2019 Registration Act’s purpose is to harmonize the 2005 Act with the

UEFJA-C for civil money judgment enforcement in the adopting jurisdictions in

Canada and the United States. Because the 2019 Registration Act is a drop-in

amendment to the 2005 Act, there is a fair bit of necessary parallel in the two

U.S. Acts. But to accomplish the harmonization between U.S. and Canadian law,

the 2019 Registration Act varies from the 2005 Act on key points. The chart

below lists the similarities and distinctions in the three acts. The summaries’

points here are paraphrased and the full text, without comments, is attached as

Appendix B. The 2019 Registration Act’s text with comments is available on

the Uniform Law Commission website.

85

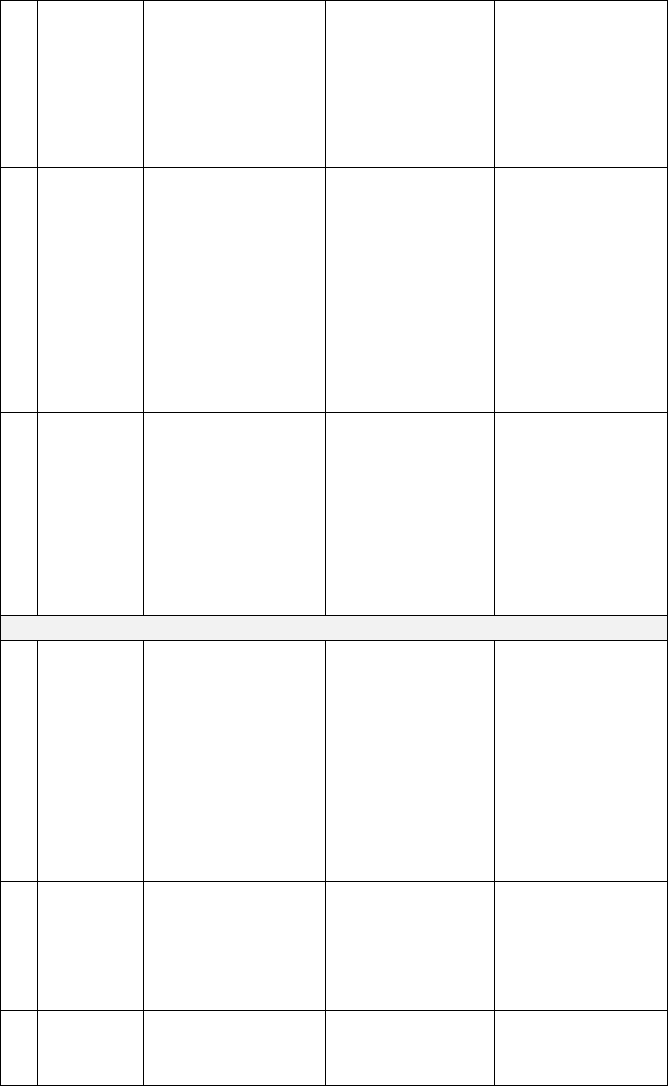

A. THREE ACTS COMPARED

Following is a side-by-side comparison of the 2005 Act, the UEFJA-C, and

the 2019 Registration Act. The 2019 Registration Act is intended to harmonize

the 2005 Act and the UEFJA-C.

83

. See id.

84

. See Unif. L. Comm’n, Transcript of the Proceedings, 2019 Annual Meeting of the Uniform Law

Commission, Tenth Session, Wednesday, July 17, 2019, at 302–10 (Unif. Law Comm’n 2019) (on file with

author and Unif. L. Cmm’n).

85

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT (UNIF. L. CMM’N 2019).

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 115

Features

2005 Act

(U.S.)

UEFJA

(Canada)

2019 Reg Act

(U.S.)

Basic Provisions

1

Definitions

§ 2 Terms defined:

foreign country

foreign-country

judgment

§ 2 Terms defined:

civil proceeding

enforcing court

foreign civil

protection order

foreign judgment

judgment creditor

judgment debtor

registration

state of origin

§ 2 Terms defined:

Canada

Canadian judgment

Consistent with the

2005 Act’s limited

definitions

2

Scope/

Applicability

§ 3(a) limits scope to

foreign-country

judgments to the extent

they (1) grant or deny

recovery for a sum of

money, and (2) are final,

conclusive and

enforceable under the

law of the rendering

state. § 3(b) excludes:

tax judgments

fines or penalties

domestic relations

Applies to foreign

judgments as defined

in § 2. § 3 excludes:

tax judgments

bankruptcy/insolvency

maintenance/

support judgments

recognizing a

judgment from

another foreign

country fines or

penalties judgments

predating this Act

§ 3.1 covers foreign

civil protection orders.

§ 6.1(3)—money

damages includes an

award by rendering

court of costs/

expenses of litigation

§ 3(a) incorporates the

2005 Act’s scope

because the

Registration Act is a

drop-in for the 2005

Act. However, § 2(2)

tracks the UEJFA-C by

barring chain

registration/recognition

(for example, it limits

judgments to those

litigated in Canada).

Comment 1 to § 3

discusses the

Registration Act’s

position on bankruptcy

but is unchanged from

the 2005 Act.

3

Application

to default

judgments

Applies to default

judgments without

expressly so stating.

§ 4(c)(6) provides a

discretionary non-

recognition ground for

judgments based only on

personal jurisdiction

which includes, but is

not necessarily limited

to, defaults. The

judgment debtor may

object if notice in the

rendering state was not

made in sufficient time

to prepare a defense. See

§ 4 comment 7.

Yes. § 4(d) excludes

only default

judgments where

notice was not

received in sufficient

time to present a

defense. § 9 adds a

jurisdictional nexus

(real and substantial

connection)

requirement for

default judgments

(burden of proof on

judgment debtor

(§ 10)).

Applies to default

judgments without

expressly so stating,

consistent with the

2005 Act.

4

Non-

monetary

awards

No. Limited by its terms

to money judgments.

Yes. § 7 gives the

enforcing court

discretion to enforce a

non-monetary award

and modify it if

necessary.

No, consistent with the

2005 Act’s limit to

money judgments.

5

Partial

Yes. § 3 provides that

Yes. § 6(1) provides a

Yes. § 3(c) expressly

116 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

enforcement

option

the Act applies to a

foreign-country

judgment to the extent

it’s within the Act’s

scope and does not

apply to the extent it

falls within an excluded

category. The enforcing

court is free to recognize

and enforce the out-of-

scope aspects under

common law or comity.

See § 3 comments 2 &

5.

court can reduce

award for punitive

damages, etc., to the

extent they would be

available in enforcing

state. § 6(2) provides a

court may reduce

excessive actual

damages, limiting to

what the enforcing

court could award.

§ 12(2) provides a

judgment creditor may

register only part of

foreign judgment.

§ 12(4)(c) provides a

creditor may seek

amendment to render

enforceable.

allows partial

registration.

Filing

6

Registration

option

No. Judgment creditors

must file a new lawsuit

or raised by

counterclaim,

crossclaim, etc. See § 6.

Yes. § 12.

Yes. § 4, and to some

extent, the entire Act is

about the use of

registration as a drop-

in alternative to the

2005 Act.

7

Recognition

option

Yes. § 7(1) provides for

recognition for

preclusion purposes and

§ 7(2) provides for

enforcement as a local

judgment.

Yes. § 11 provides for

recognition for

preclusion purposes

under the same terms

for enforcement.

No, but § 9 allows the

alternative of filing a

recognition action

under the 2005 Act.

8

Litigation

option

Yes, exclusive process,

and § 11 preserves the

common law action.

No express provision.

But contract with § 3.1

allowing judgment

creditor to proceed

under another Act

(UECJDA).

No, but § 9 allows

filing a recognition

action under the 2005

Act. As a result, the

Registration Act can

only be used for

enforcement and not

preclusion purposes.

9

Certification

requirement

No express provision.

Enforcing state’s

evidentiary laws on

authentication govern,

which may in turn look

to rendering state’s law.

Yes. § 12(4)(a)

requires a copy of the

foreign judgment

certified by proper

officer of the

rendering court.

Yes. § 4(b)(1) is based

on the UEFJA-C

§ 12(4)(a).

10

Translation

No express provision;

presumably governed by

enforcing state’s law.

Yes. § 12(4)(d).

Yes. § 4(b)(10).

11

Notice of

filing in

enforcing

state

No express provision.

But § 6 (which requires

the filing of a new

action) would require

notice under enforcing

state’s law.

§ 12(3) requires notice

to judgment debtor of

intent to register the

foreign judgment.

Yes. § 6 requires

notice of registration in

the same manner as

notice of a new claim.

12

Limitations

period

§ 9 provides the earlier

of (1) time allowed by

§ 5 provides the

earlier of (1) time

No change from the

2005 Act. See § 7.

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 117

rendering state, or (2) 15

years after date the

judgment became

effective in the

rendering state.

allowed by rendering

state, or (2) 10 years

after date the

judgment became

enforceable in the

rendering state.

13

Act defines

enforcing

court

No express provision;

presumably must be

filed in a court having

subject matter

jurisdiction. See § 6.

Yes. § 2 provides “the

superior court of

unlimited trial

jurisdiction in the

enacting province or

territory.”

No change from the

2005 Act. See § 4(a).

Defenses

14

Defenses to

registration/

recognition/

enforcement

§ 4 provides two-tiers of

defenses: mandatory and

discretionary. § 4(b) is

mandatory and bars

recognition for lack of:

impartial tribunal or

reasonable procedural

opportunities (must be

systemic), personal

jurisdiction, and subject

matter jurisdiction.

§ 4(c) provides

discretionary non-

recognition for: lack of

notice in time to prepare

a defense extrinsic fraud

public policy conflict

with a final and

conclusive judgment

conflict with a forum

clause derogating from

the rendering forum’s

jurisdiction inconvenient

forum (for judgments

based only on personal

jurisdiction) substantial

doubts about rendering

court’s integrity due

process. § 5 defines non-

exclusive bases for

personal jurisdiction:

personal service in the

rendering forum

(including transient

jurisdiction), voluntary

appearance, consent

prior to case

commencement,

human domicile, or

corporate presence

(incorporation/formation

or principal place of

business) in the

rendering state business

presence in the

rendering forum related

§ 4 provides a foreign

judgment cannot be

enforced if the:

rendering court lacked

personal or subject

matter jurisdiction as

defined in § 8 & § 9

judgment has been

satisfied judgment is

unenforceable in the

rendering state, or

appeal is pending, or

time for appeal

expired not properly

served under the

rendering state’s law,

or did not receive

notice in sufficient

time to present a

defense, and the

judgment was allowed

by default judgment

was obtained by fraud

lack of procedural

fairness and natural

justice in the rendering

state judgment is

manifestly contrary to

the enforcing state’s

public policy a parallel

case in the enforcing

state that began before

the case seeking

enforcement, or has

resulted in another

judgment or order in

the enforcing state, or

has been reduced to

judgment in foreign

state other than the

rendering state. § 10

states a foreign

judgment may not be

enforced if the

judgment debtor

shows a lack of real

No change from the

2005 Act. See § 7. The

2019 Act incorporates

by reference all

defensive grounds in

the 2005 Act. See

§ 7(b) and comment 2.

118 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

to the judgment vehicle/

aircraft operation in the

rendering forum related

to the judgment. In

addition to defenses in

§ 4 & § 5, there are

other primary defenses

such as falling outside

the Act’s scope.

and substantial

connection with the

rendering state AND

that jurisdiction was

inappropriate there.

15

Burden

§ 3(c) places the burden

on the party seeking

recognition to file a new

lawsuit and obtain a

local judgment based on

preclusion. Once filed,

§ 4(d) places a burden of

raising and proving

defenses on the

judgment debtor.

§ 10 places the burden

on judgment debtor to

establish the defenses of

lack of real/ substantial

connection,

inappropriate

jurisdiction. Other

defense sections, § 4

(reasons for refusal), § 8

(personal jurisdiction),

§ 9 (real and substantial

connection) do not

specify.

§ 7. Once an

authenticated foreign

judgment is registered

under § 4 and notice

given under § 5, the

burden is on the

judgment debtor to

establish a defense

under § 7. Failing that,

the registration results

in a local judgment

capable of

enforcement.

16

Stay

Yes. § 8 places the

burden on the judgment

debtor to show the case

is on appeal or that one

will be taken; the court

may issue a stay until

the appeal concludes,

time for appeal expires,

or defendant has failed

to prosecute the appeal.

§ 4(c) provides a

defense to

enforcement if on

appeal, or time for

filing appeal has not

run.

Yes. § 8 provides that

after filing a § 7

petition to set aside the

registration, a party

may request a stay

which can be granted

upon a showing of

likelihood of success

on the merits. The

court may require

security.

Outcome

17

Effect of

filing

There is no registration

procedure. The judgment

creditor files a new

lawsuit, gives notice to

the judgment debtor, then

moves for summary

judgment unless the

judgment debtor pleads a

defense. If judgment

creditor prevails, the

foreign judgment is

domesticated and

enforceable locally.

The filing of a

properly attested

foreign judgment

leads to registration,

notice to the judgment

debtor, and

enforcement under the

enforcing

jurisdiction’s law

unless the judgment

debtor successfully

raises a defense.

Same as the UEFJA-C.

The filing of a properly

attested foreign

judgment leads to

registration, notice to

the judgment debtor,

and enforcement under

the enforcing forum’s

law unless the

judgment debtor

successfully raises a

defense.

18

Enforcement

§ 7(2) provides

enforcement as local

judgment after

recognition which

requires summary

judgment or trial.

§ 14 provides

registered judgment is

enforceable 30 days

after filing as if it were

local judgment so long

as no successful

defenses.

§ 7 provides the same

result as under the

UEFJA-C.

19

Costs

No express provision;

presumably governed by

enforcing state’s law.

Yes. Under § 12(5), a

judgment creditor

may, if the regulations

provide, recover the

Yes. § 4(b)(6)(B)

requires listing of

Canadian costs.

§ 4(b)(7) requires listing

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 119

costs and expenses

related to the

registration of the

foreign judgment.

of post-judgment costs

up to the date of

registration; no mention

of enforcing state costs,

presumably governed by

enforcing state’s law.

20

Interest

No express provision;

presumably governed by

enforcing state’s law.

Yes. § 15 is governed

by the rendering

state’s law up to date

of currency

conversion and

thereafter by the

enforcing state’s law.

Court has discretion to

change the rate or

calculation

methodology if the

judgment creditor

would be under- or

over-compensated.

§ 4(b)(6)(A) requires

listing in the

registration the rate

and accrual of interest

awarded by the

rendering court; does

not mention the cutoff

date when Canadian

law no longer governs,

or the effect of the

Canadian rate on the

resulting enforcing

state’s judgment.

21

Currency

conversion

No express provision;

presumably governed by

the enforcing state’s

law.

Yes. § 13 requires

judgment creditor’s

statement that the

judgment will be

converted to local

currency on the

conversion date; the

conversion date is the

last day, before the

day on which the

judgment debtor

makes a payment to

the judgment creditor

under the registered

foreign judgment, on

which the bank quotes

a Canadian dollar

equivalent to the other

currency.

No mention, same as

2005 Act. See § 4

Comment 11, which

notes the intent to track

the 2005 Act on this

point.

As the chart shows, the 2019 Registration Act follows its parent Act—the

2005 Act—on such fundamental points as definitions, scope, defenses, and

several of the issues left to the enforcing state’s law. On the other hand, the

Registration Act accomplishes its harmonization task with key sections on the

filing procedure (registration rather than a new legal action), notice, the

expedited effect, changes in the stay provision, the petition to set aside, and the

provisional remedies available upon registration.

B. A DRY RUN THROUGH REGISTERING AND OBJECTING

The chart above and this brief synopsis are paraphrases of the Act’s

elements. For a thorough understanding of the 2019 Registration Act, read its

text in Appendix B or better still, read the Act and comments at the Uniform

120 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

Law Commission website.

86

The few case citations in this Subpart are of course

for enforcement under the 2005 Act or the 1962 Act, and not the 2019

Registration Act which is just now being sent to the states.

1. Filing

a. Compliance

Although some cases hold that substantial compliance with filing

requirements is enough,

87

certain elements are no doubt necessary for any court.

One is a copy of the foreign-country judgment authenticated by the rendering

court.

88

As to other requirements, the 2019 Registration Act includes a form as

an appendix to Section 4.

89

The form is not required when filing, but its use

makes acceptance more likely in states adopting the 2019 Act substantially

intact.

b. Who May File

The named judgment creditor of course may file. The 2019 Act also

contemplates that the judgment creditor’s assignees or successors may file.

90

What about the judgment creditor’s status in the enforcing state? In a New York

case under the 1962 Act, a judgment debtor objected that the judgment creditor

was neither present in nor registered to do business in the enforcing state. The

court held that the state’s corporate registration requirement did not apply to

parties using the court to enforce a foreign judgment.

91

c. No Chain Recognition

A judgment creditor may not use the 2019 Registration Act to register a

Canadian judgment that merely recognized or domesticated another judgment.

92

The Canadian judgment must be original, one that was litigated in the rendering

court. This is consistent with the UEFJA-C and the drafting committee thought

it essential for harmonization.

93

86

. See id.; see also id., Prefatory Note at 4–5.

87

. See Frymer v. Brettschneider, 696 So. 2d 1266, 1267–68 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1997) (decided under

1962 Act).

88

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT § 4(b)(1); see also Ningbo FTZ

Sanbang Indus. Co. v. Frost Nat’l Bank, 338 F. App’x 415, 417 (5th Cir. 2009) (upholding district court’s

dismissal for failure to state a claim because the judgment creditor did not produce an authenticated copy of the

Chinese judgment) (decided under 1962 Act).

89

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT § 4(d).

90

. See id. § 4(b)(3).

91

. See Gemstar Can., Inc. v. George A. Fuller Co., 6 N.Y.S.3d 552, 554 (App. Div. 2015) (decided under

1962 Act).

92

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT § 2(2).

93

. See Uniform Enforcement of Foreign Judgments Act §3(d) (Unif. L. Conf. Can. 2003) (Can.).

November 2020] MONEY JUDGMENT ENFORCEMENT 121

d. What to Seek

Judgment creditors are limited to the monetary amount stated in the

rendering court’s final judgment, minus payments, plus allowable costs.

94

Currency conversion is not addressed in the 2019 Registration Act but is

mentioned in a comment, which notes that conversion will be handled under the

enforcing state’s law, as in the 2005 Act.

95

What if there is a delay because of

appeal in the rendering forum, and the converted amount changes because of

drastic currency fluctuations? There are no cases on point, but it is likely that

any change other than appropriate conversion would amount to re-litigation and

therefore be inappropriate.

96

e. Limitations

The 2019 Registration Act defers to the 2005 Act for filing limitations.

97

The 2005 Act requires that the judgment be filed within the earlier of the time

during which the foreign-country judgment is effective in the foreign country or

fifteen years from the date that the foreign-country judgment became effective

in the foreign country.

98

The limitations rule in the 2005 Act (and incorporated

into the 2019 Registration Act) applies to the filing period in the enforcing state.

Any issue of limitations in the rendering forum would have to be raised there

and cannot be relitigated in the enforcing forum.

99

f. Alternate Procedures

Section 9 of the 2019 Registration Act gives judgment creditors the option

of registering an appropriate Canadian judgment, or seeking recognition under

the 2005 Act by filing a legal action.

100

Either is available, but not both.

101

For

judgments (or portions of judgments) not within the 2019 Registration Act’s

scope, judgment creditors may seek recognition under another recognition

statute or the common law.

102

2. Notice

The 2019 Registration Act has a detailed notice provision. This differs from

the 2005 Act, which has no notice provision but instead requires the filing of a

new recognition action under the enforcing state’s law, which implicitly requires

94

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT § 4(b)(6)–(8).

95

. See id. § 4 cmt. 11.

96

. See Leidos, Inc. v. Hellenic Republic, 881 F.3d 213, 220 (D.C. Cir. 2018) (filing a petition to enforce

arbitration rather than an action under the 1962 or 2005 Acts; holding that the award had to be converted under

current exchange rates and any other approach was relitigation).

97

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT § 7(b)(1); id. cmt. 3.

98

. See UNIF. FOREIGN-COUNTRY MONEY JUDGMENTS RECOGNITION ACT § 9 (UNIF. L. CMM’N 2005).

99

. See Manco Contracting Co. (W.L.L.) v. Bezdikian, 195 P.3d 604, 612–16 (Cal. 2008) (explaining the

functions of the limitations period in the rendering forum and the enforcing forum).

100

. See UNIF. REGISTRATION OF CANADIAN MONEY JUDGMENTS ACT § 9(b).

101

. See id. § 9(c).

102

. See id. § 9 cmt. 5.

122 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 72:99

use of the enforcing state’s notice rules.

103

Because the 2019 Act speeds up

enforcement unless objections are raised, the notice requirements are crucial,

and the 2019 Act specifies both the manner of service and the notice’s content.

a. Manner of Service

The 2019 Act requires the registering party to “cause notice of registration

to be served on the person against whom the judgment has been registered.”

104

The notice must be served in the same manner as a summons and complaint is

served under the enforcing state’s version of the 2005 Act.

105

b. Content