Assessing and Improving Your Farm Cash Flow

Fact Sheet 541

What Is Liquidity?

Liquidity refers to the ability of your farm

to generate enough cash to meet financial

obligations as they come due without disrupt-

ing the normal operation of the farm

business. Figure 1 illustrates this concept.

Cash flows into the business from various

sources such as crop and livestock sales, other

farm receipts, sale of capital assets, nonfarm

receipts, and borrowed money. You use this

money to meet financial obligations like

production expenses, capital expenditures,

loan payments, and family living expendi-

tures. Inflows and outflows seldom coincide

with each other. Consequently, farm managers

need to manage a liquidity or cash reserve to

prevent cash shortages from disrupting

normal farm business operations and to

prevent noninterest-earning cash reserves

from building up.

Cash Inflows

• Crop, livestock, and livestock product sales,

the primary source of cash for your farm

business, are critical to maintaining

the liquidity reserve of the farm busi-

ness. Some enterprises, such as a dairy,

generate a relatively even flow of cash

into the farm business over the produc-

tion year. Other enterprises like corn or

feeder livestock result in sporadic cash

inflows as sales are lumped into relative-

ly few transactions during the course of

the production period.

• Other farm receipts often constitute a

substantial cash inflow to your farm

business. Typical items include payments

from participation in government com-

modity programs, income from custom

work performed, and co-op dividends.

• Nonfarm receipts include items such as

income from an off-farm job, cash

infusion from nonfarm savings and

investments, interest earned on nonfarm

investments, and capital provided by

outside investors.

Figure 1. Farm Business Liquidity. (Cash flow)

Source: Cash Flow Planning and Management, Publication 933.

Agricultural Extension Service: University of Tennessee, October

1983.

• Sale of capital assets include the sporadic

cash inflows from the sale of land,

buildings, machinery, breeding livestock,

and tools.

• Borrowed money is shown in Figure 1

as a cash inflow entering the liquidity

reserve from the side rather than the top.

Borrowed money is often considered a

residual source of cash used to maintain

your liquidity reserve when cash out-

flows exceed the sometimes sporadic

inflows of the four sources mentioned

previously. Borrowed money can take

the form of short-term loans to cover

operating costs, intermediate-term loans

for assets such as machinery and live-

stock, or long-term loans such as farm

mortgages on land and buildings.

Cash Outflows

• Production expenses constitute a relatively

large draw on your liquidity reserve.

These expenses include seed, fertilizer,

chemicals, feed, hired labor, repairs and

others. If you fail to maintain the liquidity

reserve to meet these expenses, your farm

production could immediately decrease

or you could pay a bigger interest on

borrowed money.

• Capital expenditures include cash outlays

for replacing and adding machinery and

breeding livestock, and purchase of

land and buildings. These outlays are

important for maintaining and increas-

ing the growth of your farm business.

These cash outflows are sporadic and

often involve large amounts of money.

Consequently, you need to carefully

plan to ensure a liquidity reserve to meet

these expenditures.

• Loan payments on borrowed money can

be made when cash inflows from non-

borrowed sources exceed cash outflows.

Consider this when formulating your

loan payment schedules.

• Family living expenditures are sometimes

overlooked as being secondary to the

other cash outflows. Actually, certain

basic family living expenses must be

covered as indicated by the fact that

money earmarked for other uses in the

farm business sometimes finds its way

into the family budget.

How Do I Use a Cash

Flow Statement to Monitor

Liquidity?

The best way to maintain your liquidity

reserve is through cash flow planning. The

tool used in this process is the “Cash Flow

Statement.” It records the timing and size of

cash inflows and outflows that occur over a

given accounting period, normally one year.

The accounting period is broken down into

smaller periods, usually months.

You normally keep two kinds of cash flow

statements for each accounting period: pro-

jected and actual. The projected cash flow

statement is completed at the beginning of

the accounting period and projects expected

cash inflows and outflows for the period to

estimate the liquidity reserve or ending cash

balance for each month. If the ending cash

balance is short in any month, you can make

plans for borrowing or setting up a line of

credit.

As the accounting period progresses, keep

an actual cash flow statement to record cash

transactions as they take place. Then com-

pare the actual cash flow statement with the

projected cash flow statement to see if things

are going as planned, to devise remedies for

solving previously unforeseen problems, or to

take advantage of opportunities not

anticipated. At the end of the accounting

period, use the actual cash flow statement to

estimate the projected cash flow statement

for the next accounting period. The formats

for cash flow statements vary but most con-

tain similar information. Table 1 shows an

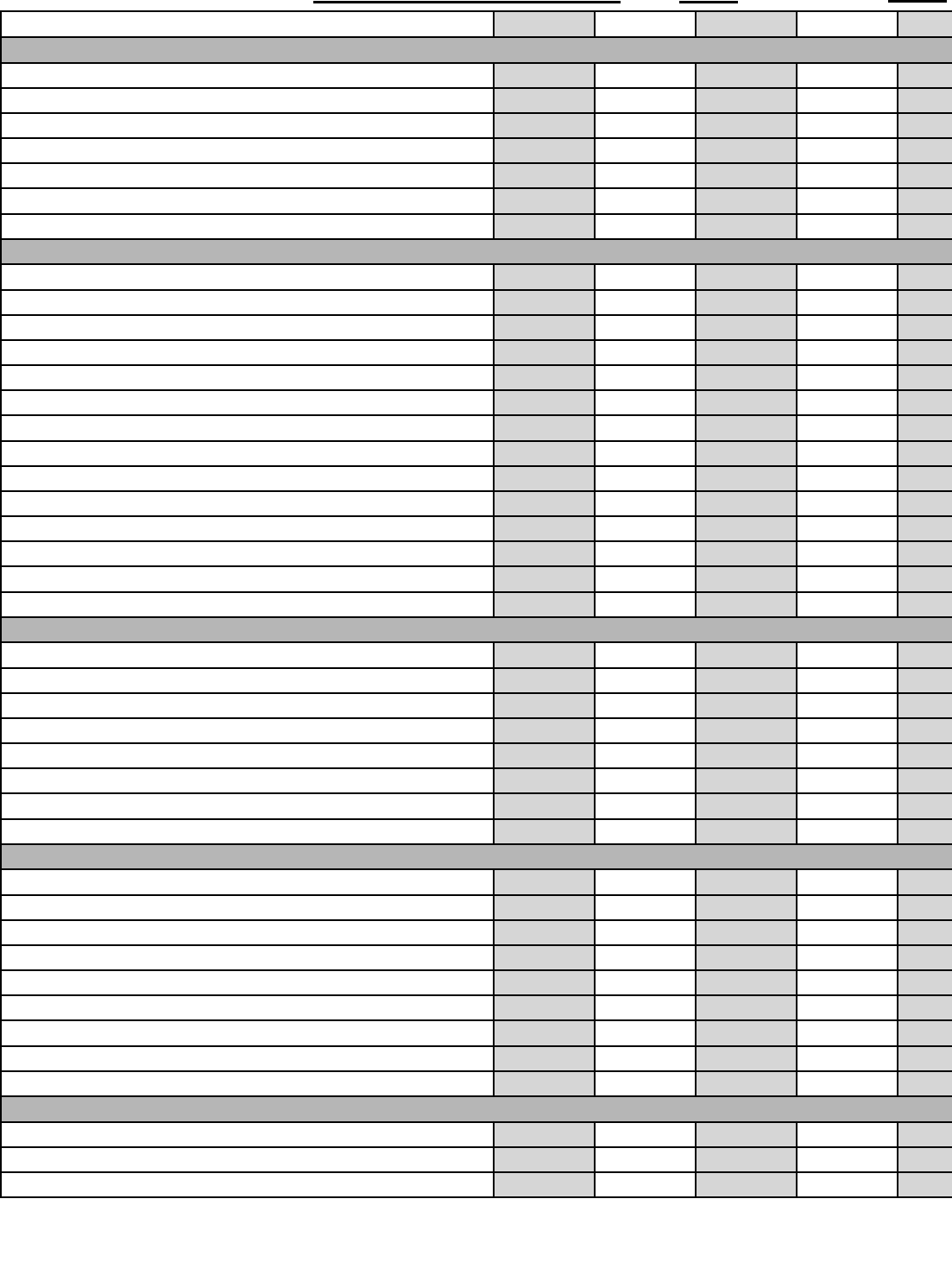

example of a projected cash flow statement.

Blank cash flow statements are also included

for your use.

The sample projected cash flow statement

summarizes monthly cash inflows and

outflows for the fictitious Whitmer farm

for one year. The first column lists the trans-

actions. The second column summarizes

the total cash inflows and outflows from the

previous year. The next twelve columns

project the monthly cash inflows and out-

2

3

flows for the coming year. The last column

totals the monthly projections. The main

categories of entries are: cash inflows, cash

operating expenses, other cash outflows, cash

flow summary, and loan balances end

of period.

Cash Inflows

The Whitmer farm produces corn and

soybeans. Some of the corn is used to feed

purchased feeder pigs. The remaining corn

and soybeans are sold. The farm receives

subsidy payments from participation in

government commodity programs. The

owner is also employed in a part-time off-

farm job during the winter. The cash inflow

section shows that during the previous year

the Whitmers generated $139,510 (line 7)

from these various sources. Their total pro-

jected cash inflow for the year is estimated at

$146,770 (line 7).

Cash Operating Expenses

The Whitmerses’ cash operating expenses

last year total $85,390 (line 21). Expenses are

projected for the coming year based on last

year’s figures, expected price changes, and

any changes in production that are expected

for the coming year. Their total cash operat-

ing expenses for the year are projected to be

$89,600 (line 21).

Other Cash Outflows

In March, the Whitmers plan to replace a

tractor. With a trade-in allowance on the old

tractor, the cash “boot” of the new tractor will

be $29,700 (line 22). The Whitmers project

family withdrawals to be $1,300 a month

(line 23). Taxes of $4,200 (line 24) are

projected to be paid in March. On lines 25

and 26, the intermediate loan principal and

interest payments are listed for April and

October. Principal and interest on the farm

mortgage are paid in February and listed

on lines 27 and 28. These cash outflows are

totaled with cash operating expenses on line

29. The total cash outflow, including cash

operating expenses for the year, is projected

to be $163,705, compared with $117,305 for

the previous year.

Cash Flow Summary

The cash flow summary is important

because it projects the Whitmerses’ liquidity

reserve for the coming year, which determines

when cash surpluses and shortfalls might take

place. New borrowings and loan payments

can then be made to maintain a liquid-

ity reserve—ending cash balance—for each

month. The Whitmers wish to maintain a

liquidity reserve of at least $1,500 at all times.

The cash flow summary shows how they

maintain this reserve (many farm managers

have a line of credit to reduce the liquidity

reserve or maintain the liquidity reserve in an

interest-bearing account).

The Whitmers begin with a January cash

balance of $1,500 (line 30), which is the end-

ing cash balance from the previous December.

They have cash inflows of $15,200 for January

(line 7) and cash outflows of $3,200 (line 29).

The difference of $12,000 is listed on line 31.

When added to the beginning balance, this

creates a cash surplus of $13,500 (line 32).

The Whitmers have an operating loan bal-

ance from the previous year and have decided

to use the cash surplus to pay off the $11,250

principal and $450 interest on this loan. This

will leave them with an $1,800 ending cash

balance for January (line 38), which becomes

the beginning cash balance for February.

In February, the difference in cash inflows

and outflows is $10,520. Adding this to the

$1,800 beginning cash balance results in a

February ending cash balance of $12,320.

Because the Whitmers know they will have a

cash shortfall in March, they plan to hold the

entire $12,320 to help cover this shortfall. In

March, cash outflows are projected to exceed

cash inflows by $37,545, mainly because

of the purchase of the new tractor. The

Whitmers plan to meet this shortfall by using

the surplus from February and by taking out

a machinery loan for $27,500 (line 34). This

will leave an ending cash balance of $2,275.

The Whitmers project their cash outflows

from April through June to exceed cash

inflows. They plan to maintain the $1,500

ending cash balance each month by

increasing the operating loan. Sale of

market hogs in July will create a cash surplus

for July and August. Another cash deficit in

September will be covered by an increase

✔

4

Table 1. A cash flow statement of the Whitmer farm

Cash Flow Statement Name Whitmer Farm Projected for 19 91 Actual for 19 90 Date completed Jan. 1991

Period Last Year

Jan. Feb. March April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec.

Totals

Cash Inflows

1. Crop sales

98,210 15,500 78,500 12,000 106,000

2. Livestock and livestock product sales

23,414 14,400 10,350 3,840 28,590

3. Government payments

12,786 6,700 2,280 8,980

4. Capital sales

2,300 0

5. Other farm income

0

6. Nonfarm income

2,800 800 800 800 800 3,200

7. Total cash inflow (Lines 1 thru 6)

139,510 15,200 23,000 3,80 0 0 0 10,350 0 0 82,340 12,000 800 146,770

Cash Operating Expenses

8. Seed

7,100 5,000 2,500 7,500

9. Fertilizer, lime, chemicals

25,800 21,500 5,500 27,000

10. Feed

3,750 800 600 800 700 800 1,100 4,800

11. Livestock purchased for resale

9,165 3,825 5,750 9,575

12. Vet, medicine, breeding fees

250 50 50 50 50 50 50 300

13. Fuel, oil, lubricants

4,25 350 350 350 450 500 500 900 500 250 4,150

14. Utilities

1,740 200 200 150 150 150 150 150 150 150 150 200 200 2,000

15. Repairs

2,740 100 100 300 300 500 500 200 200 300 400 200 100 3,200

16. Taxes, insurance

3,625 950 1,725 950 3,625

17. Hired labor

1,80 450 300 400 1,150

18. Rent, leases

13,500 0 13,500 13,500

19. Machine hire

10,500 10,500 10,500

20. Supplies, miscellaneous, others

2,115 400 150 150 150 150 150 400 150 150 150 150 150 2,300

21. Total cash operating expenses (Lines 8 thru 20)

85,390 1,900 450 5,425 5,600 27,400 7,50 1,500 1,000 9,425 2,950 26,200 700 89,600

Other Cash Outflows

22. Capital purchases

29,700 29,700

23. Family living

14,400 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 15,600

24. Other withdrawls and income taxes

1,475 4,200 4,200

25. Intermediate loan principal payments

3,600 1,850 8,250 10,100

26. Intermediate loan interest payments

1,710 875 2,900 3,775

27. Long-term loan principal payments

2,750 2,900 2,900

28. Long-term loan interest payments

7,980 7,830 7,830

29. Total cash outflow (Lines 21+22 thru 28)

117,305 3,200 12,480 40,625 9,625 28,700 8,350 2,800 2,300 10,725 15,400 27,500 2,000 163,705

Cash Flow Summary

30. Beginning cash balance

1,500 1,800 12,320 2,275 1,500 1,500 1,500 9,50 6,750 1,500 18,200 2,700

31. Inflows - outflows (Lines 7-29)

12,000 10,520 (545) (625) (700) 8,350 7,550 (300) (725) 66,940 (500) (200)

32. Cash position (Lines 30+31)

13,500 12,320 (225) (350) (200) (850) 9,50 6,750 (975) 68,440 2,700 1,500

33. New borrowing: operation

8,850 28,700 8,350 5,475

34. New borrowing: intermediate

27,500

35. New borrowing: long-term

36. Operating loan principal payments

11,250 47,890

37. Operating loan interest payments

450 2,350

38. Ending cash balance (Lines 32+33+34+35-36-37)

1,800 12,320 2,275 1,500 1,500 1,500 9,50 6,750 1,500 18,200 2,700 1,500

Loan Balances End of Period

39. Operating (previous period line 39+33-36)

11,250 0 0 0 8,850 37,550 45,900 45,900 45,900 51,375 3,485 3,485 3,485

40. Intermediate (previous period line 40+34-25)

17,000 17,000 17,000 44,500 42,650 42,650 42,650 42,650 42,650 42,650 34,400 34,400 34,400

41. Long-term (previous period line 41+35-27)

88,700 88,700 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 88,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800

Table 1. A cash flow statement of the Whitmer farm

Cash Flow Statement Name Whitmer Farm Projected for 19 91 Actual for 19 90 Date completed Jan. 1991

Period Last Year

Jan. Feb. March April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec.

Totals

Cash Inflows

1. Crop sales

98,210 15,500 78,500 12,000 106,000

2. Livestock and livestock product sales

23,414 14,400 10,350 3,840 28,590

3. Government payments

12,786 6,700 2,280 8,980

4. Capital sales

2,300 0

5. Other farm income

0

6. Nonfarm income

2,800 800 800 800 800 3,200

7. Total cash inflow (Lines 1 thru 6)

139,510 15,200 23,000 3,80 0 0 0 10,350 0 0 82,340 12,000 800 146,770

Cash Operating Expenses

8. Seed

7,100 5,000 2,500 7,500

9. Fertilizer, lime, chemicals

25,800 21,500 5,500 27,000

10. Feed

3,750 800 600 800 700 800 1,100 4,800

11. Livestock purchased for resale

9,165 3,825 5,750 9,575

12. Vet, medicine, breeding fees

250 50 50 50 50 50 50 300

13. Fuel, oil, lubricants

4,25 350 350 350 450 500 500 900 500 250 4,150

14. Utilities

1,740 200 200 150 150 150 150 150 150 150 150 200 200 2,000

15. Repairs

2,740 100 100 300 300 500 500 200 200 300 400 200 100 3,200

16. Taxes, insurance

3,625 950 1,725 950 3,625

17. Hired labor

1,80 450 300 400 1,150

18. Rent, leases

13,500 0 13,500 13,500

19. Machine hire

10,500 10,500 10,500

20. Supplies, miscellaneous, others

2,115 400 150 150 150 150 150 400 150 150 150 150 150 2,300

21. Total cash operating expenses (Lines 8 thru 20)

85,390 1,900 450 5,425 5,600 27,400 7,50 1,500 1,000 9,425 2,950 26,200 700 89,600

Other Cash Outflows

22. Capital purchases

29,700 29,700

23. Family living

14,400 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 1,300 15,600

24. Other withdrawls and income taxes

1,475 4,200 4,200

25. Intermediate loan principal payments

3,600 1,850 8,250 10,100

26. Intermediate loan interest payments

1,710 875 2,900 3,775

27. Long-term loan principal payments

2,750 2,900 2,900

28. Long-term loan interest payments

7,980 7,830 7,830

29. Total cash outflow (Lines 21+22 thru 28)

117,305 3,200 12,480 40,625 9,625 28,700 8,350 2,800 2,300 10,725 15,400 27,500 2,000 163,705

Cash Flow Summary

30. Beginning cash balance

1,500 1,800 12,320 2,275 1,500 1,500 1,500 9,50 6,750 1,500 18,200 2,700

31. Inflows - outflows (Lines 7-29)

12,000 10,520 (545) (625) (700) 8,350 7,550 (300) (725) 66,940 (500) (200)

32. Cash position (Lines 30+31)

13,500 12,320 (225) (350) (200) (850) 9,50 6,750 (975) 68,440 2,700 1,500

33. New borrowing: operation

8,850 28,700 8,350 5,475

34. New borrowing: intermediate

27,500

35. New borrowing: long-term

36. Operating loan principal payments

11,250 47,890

37. Operating loan interest payments

450 2,350

38. Ending cash balance (Lines 32+33+34+35-36-37)

1,800 12,320 2,275 1,500 1,500 1,500 9,50 6,750 1,500 18,200 2,700 1,500

Loan Balances End of Period

39. Operating (previous period line 39+33-36)

11,250 0 0 0 8,850 37,550 45,900 45,900 45,900 51,375 3,485 3,485 3,485

40. Intermediate (previous period line 40+34-25)

17,000 17,000 17,000 44,500 42,650 42,650 42,650 42,650 42,650 42,650 34,400 34,400 34,400

41. Long-term (previous period line 41+35-27)

88,700 88,700 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 88,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800 85,800

5

in the operating loan. A cash surplus from

crop sales in October will be used to reduce

the operating loan and carry the Whitmers

through November and December. They end

the year with an ending cash balance

of $1,500.

Lines 33 to 35 list new borrowings for

operating and for intermediate- and long-

term loans. Lines 36 and 37 list payments of

operating loan principal and interest. The

question is sometimes asked why principal

and interest payments for intermediate- and

long-term loans are included in the “other

cash outflows” section rather than the “cash

flow summary” section. The reason is that

intermediate- and long-term loan payments

are usually scheduled for specific months

when the loans are made, while operating

loan payments remain flexible. In fact, using

the “cash flow summary” in the cash flow

statement is the best way to schedule operat-

ing loan payments. The operating loan acts as

the primary tool for maintaining the level of

cash reserve. For farms that operate on equity

capital rather than operating loans, the cash

flow statement determines when cash sur-

pluses are available for alternative uses.

Loan Balances End of Period

The final section of the cash flow statement

is the “loan balances end of period.” This

section keeps a running total of operating

and intermediate- and long-term loan prin-

cipal balances. On the Whitmer farm, loan

principal balances at the end of the previous

year are $11,250 (line 39) for operating loans,

$17,000 (line 40) for intermediate loans, and

$88,700 (line 41) for long-term loans. These

balances are projected to fluctuate through

the coming year as payments are made and

new money is borrowed.

For example, the operating loan balance

is decreased in January by subtracting the

loan payment of $11,250 and adding any

additional borrowings (in the example there

are none). These calculations continue for

each successive month. On the Whitmer

farm the operating loan balance increases in

April through June and also in September. In

October, it is reduced below the January start-

ing level. Intermediate- and long-term loan

balances are projected to fluctuate through

the year. The intermediate loan balance ends

almost twice as high as the beginning balance

because of the tractor purchase. The long-

term loan balance ends at a lower level than

the beginning balance.

Hints for Cash Flow Planning

The example projected a cash flow

statement for the coming year. As the year

progresses, the Whitmers will fill out an

actual cash flow statement for each month,

listing inflows and cash operating expenses

and other cash outflows. They will then fill

out the cash flow summary section showing

actual loan balances in the “loan balances

end of period” section. The actual cash flow

statement can then be compared with their

projections to improve the management of

the farm. Thus, the actual cash flow state-

ment from this year can be used to project

the cash flow statement for next year. By

doing this, the Whitmers will always know

that they have a cash reserve and will not be

surprised by cash shortfalls.

Projecting a cash flow statement for the

first time is sometimes difficult. Farm records

are the first place you look for information

when you’re completing the cash flow

statement (see Fact Sheet 542, “Developing

and Improving Your Farm Records”). Your

previous year’s actual entries from farm

records, tax forms, or checkbook registers

are useful sources of information. Good crop

and livestock budgets provide necessary

information for projecting future cash flows

(see Fact Sheet 545, “Enterprise Budgeting in

Farm Management Decisionmaking”).

Also, consider changes in the farm business

that are expected to take place the coming

year, such as crop rotations, new livestock

enterprises, or sales and purchases of capital

assets. Your first cash flow projection may

not be as accurate as you would like, but it

will provide important planning information.

As cash flow statements are regularly

developed, projections in future years will

become more accurate.

6

Are There Ways to Solve

Cash Flow Problems?

Some Helpful Suggestions

Most farms at one time or another

experience cash flow problems. A cash flow

statement is one of the best ways to pinpoint

these problems, and there are ways to deal

with them. No one strategy will work at all

times. Rather, a combination of strategies

is the basis for solving cash flow problems.

However, in adopting methods to remedy

these problems, be sure the strategies used do

not adversely affect profitability. Treating cash

flow problems at the expense of profitability

is a short-term remedy that may have bad

long-term effects.

Improving profitability. Cash flow

problems may be the symptom of the greater

problem of low profitability. In approaching

cash flow problems, first analyze profits and

profitability (see Fact Sheet 539, “Assessing

and Improving Your Farm Profitability”).

Increasing profits and profitability is often the

best way to remedy cash flow problems. Once

the farm is profitable, you can then

concentrate on cash flow problems.

Identifying the problems beforehand.

One way you can prevent cash flow problems

is to have cash flow statements so you can

identify problems before they occur. This

gives you time to alter your plans and remedy

the problems by timing cash inflows and cash

outflows, if you want to maintain a liquidity

reserve.

Changing production plans. Carefully

look at the combination of enterprises on

the farm. Perhaps another crop rotation or

livestock enterprise would increase cash flow

and allow you to maintain profitability at the

same time. For example, introducing legume

hay into a rotation may bring in some needed

cash during the summer months. You can

maintain profitability through lower nitrogen

fertilizer costs for subsequent crops.

Managing expenditures. An effective way

to improve your cash flow is through cost

control. Frequently check to see if levels of

inputs are economical. Are you using the best

seeds and seeding rates? Is fertilization at an

economically favorable level? Can you reduce

the use of commercial fertilizer through

better management of livestock wastes?

Will integrated pest management instead

of routine spraying reduce pesticide costs?

Can you lower purchased feed costs through

improved management of forage costs and

farm-produced concentrates? Is feed

conversion being emphasized in forage

testing and balancing feed rations?

Can you cut down on veterinary and

medicine bills through careful management

of herd health? Can you manage labor better

to decrease expensive capital outlays? Is there

better machinery that would improve labor

efficiency? Can you cut down on machin-

ery costs through reduced tillage methods?

Can repair bills be reduced through onfarm

repairs? Can you lower interest costs through

better loan rates or timing of loans?

Scrutinize every cost to see if you can

make reductions without adversely affecting

profitability.

Improving marketing plans. For non-

perishable commodities, you have some

flexibility in timing sales. Improving farm

profitability should be your main goal in

formulating a marketing plan. However,

you should also consider cash needs in

timing sales.

Leasing or renting. The down payments

and loan payments associated with

purchasing land, buildings, and machinery

sometimes put a heavy burden on cash flow.

Leasing or rental payments on these may be

considerably lower and will free cash that you

need for other obligations. However, be sure

to assess the impact of these leasing and

rental arrangements on the profitability of

your farm operation.

Reducing living expenses. Carefully

review your family budget. Record all

family expenditures. Many families are sur-

prised by how much they spend for personal

living expenses. Distinguish between

necessities and wants. Postpone unneeded

family expenditures. Base family spending on

the performance of the farm business and/or

off-farm income. Be realistic in determining the

amount of family withdrawals the farm

can support.

Taking an off-farm job. One or both

spouses could seek part-time or full-time

employment off the farm. More and more,

7

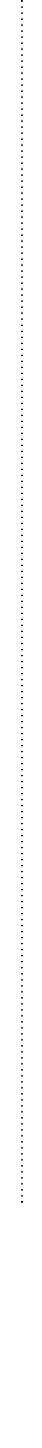

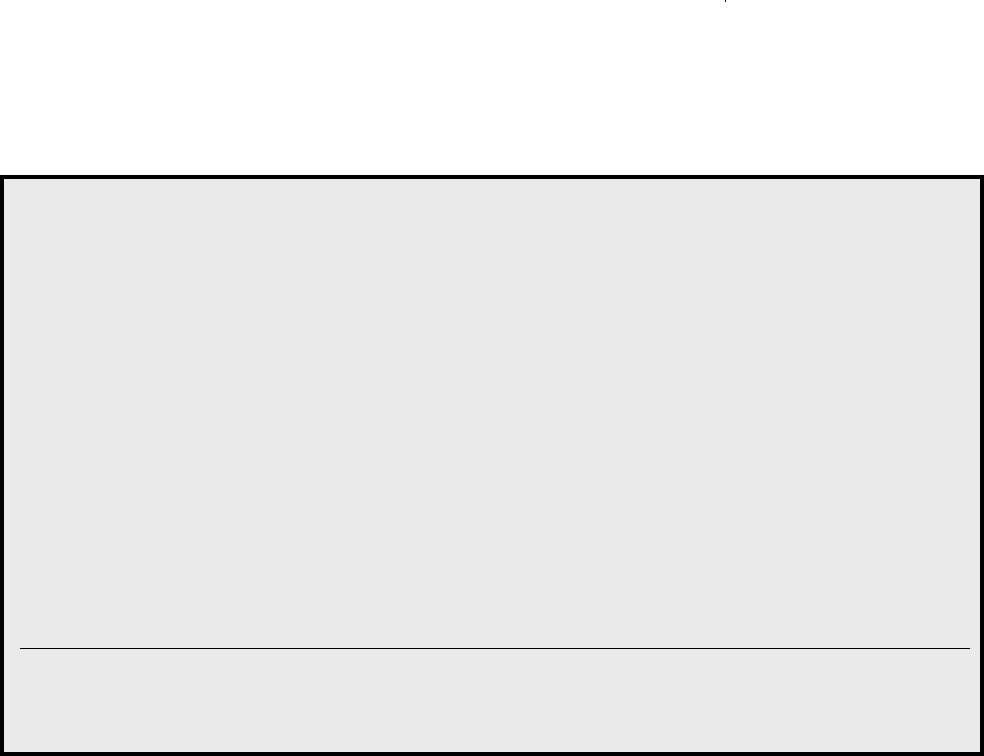

Cash Flow Statement Name Projected for 20 Actual for 20 Date completed

Period Last Year

Totals

Cash Inflows

1. Crop sales

2. Livestock and livestock product sales

3. Government payments

4. Capital sales

5. Other farm income

6. Nonfarm income

7. Total cash inflow (Lines 1 thru 6)

Cash Operating Expenses

8. Seed

9. Fertilizer, lime, chemicals

10. Feed

11. Livestock purchased for resale

12. Vet, medicine, breeding fees

13. Fuel, oil, lubricants

14. Utilities

15. Repairs

16. Taxes, insurance

17. Hired Labor

18. Rent, leases

19. Machine hire

20. Supplies, miscellaneous, others

21. Total cash operating expenses (Lines 8 thru 20)

Other Cash Outflows

22. Capital purchases

23. Family living

24. Other withdrawls and income taxes

25. Intermediate loan principal payments

26. Intermediate loan interest payments

27. Long-term loan principal payments

28. Long-term loan interest payments

29. Total cash outflow (Lines 21+22 thru 28)

Cash Flow Summary

30. Beginning cash balance

31. Inflows - outflows (Lines 7-29)

32. Cash position (Lines 30+31)

33. New borrowing: operation

34. New borrowing: intermediate

35. New borrowing: long-term

36. Operating loan principal payments

37. Operating loan interest payments

38. Ending cash balance (Lines 32+33+34+35-36-37)

Loan Balances End of Period

39. Operating (previous period line 39+33-36)

40. Intermediate (previous period line 40+34-25)

41. Long-term (previous period line 41+35-27)

8

Cash Flow Statement Name Projected for 20 Actual for 20 Date completed

Period Last Year

Totals

Cash Inflows

1. Crop sales

2. Livestock and livestock product sales

3. Government payments

4. Capital sales

5. Other farm income

6. Nonfarm income

7. Total cash inflow (Lines 1 thru 6)

Cash Operating Expenses

8. Seed

9. Fertilizer, lime, chemicals

10. Feed

11. Livestock purchased for resale

12. Vet, medicine, breeding fees

13. Fuel, oil, lubricants

14. Utilities

15. Repairs

16. Taxes, insurance

17. Hired Labor

18. Rent, leases

19. Machine hire

20. Supplies, miscellaneous, others

21. Total cash operating expenses (Lines 8 thru 20)

Other Cash Outflows

22. Capital purchases

23. Family living

24. Other withdrawls and income taxes

25. Intermediate loan principal payments

26. Intermediate loan interest payments

27. Long-term loan principal payments

28. Long-term loan interest payments

29. Total cash outflow (Lines 21+22 thru 28)

Cash Flow Summary

30. Beginning cash balance

31. Inflows - outflows (Lines 7-29)

32. Cash position (Lines 30+31)

33. New borrowing: operation

34. New borrowing: intermediate

35. New borrowing: long-term

36. Operating loan principal payments

37. Operating loan interest payments

38. Ending cash balance (Lines 32+33+34+35-36-37)

Loan Balances End of Period

39. Operating (previous period line 39+33-36)

40. Intermediate (previous period line 40+34-25)

41. Long-term (previous period line 41+35-27)

9

Cash Flow Statement Name Projected for 20 Actual for 20 Date completed

Period Last Year

Totals

Cash Inflows

1. Crop sales

2. Livestock and livestock product sales

3. Government payments

4. Capital sales

5. Other farm income

6. Nonfarm income

7. Total cash inflow (Lines 1 thru 6)

Cash Operating Expenses

8. Seed

9. Fertilizer, lime, chemicals

10. Feed

11. Livestock purchased for resale

12. Vet, medicine, breeding fees

13. Fuel, oil, lubricants

14. Utilities

15. Repairs

16. Taxes, insurance

17. Hired Labor

18. Rent, leases

19. Machine hire

20. Supplies, miscellaneous, others

21. Total cash operating expenses (Lines 8 thru 20)

Other Cash Outflows

22. Capital purchases

23. Family living

24. Other withdrawls and income taxes

25. Intermediate loan principal payments

26. Intermediate loan interest payments

27. Long-term loan principal payments

28. Long-term loan interest payments

29. Total cash outflow (Lines 21+22 thru 28)

Cash Flow Summary

30. Beginning cash balance

31. Inflows - outflows (Lines 7-29)

32. Cash position (Lines 30+31)

33. New borrowing: operation

34. New borrowing: intermediate

35. New borrowing: long-term

36. Operating loan principal payments

37. Operating loan interest payments

38. Ending cash balance (Lines 32+33+34+35-36-37)

Loan Balances End of Period

39. Operating (previous period line 39+33-36)

40. Intermediate (previous period line 40+34-25)

41. Long-term (previous period line 41+35-27)

10

Cash Flow Statement Name Projected for 20 Actual for 20 Date completed

Period Last Year

Totals

Cash Inflows

1. Crop sales

2. Livestock and livestock product sales

3. Government payments

4. Capital sales

5. Other farm income

6. Nonfarm income

7. Total cash inflow (Lines 1 thru 6)

Cash Operating Expenses

8. Seed

9. Fertilizer, lime, chemicals

10. Feed

11. Livestock purchased for resale

12. Vet, medicine, breeding fees

13. Fuel, oil, lubricants

14. Utilities

15. Repairs

16. Taxes, insurance

17. Hired Labor

18. Rent, leases

19. Machine hire

20. Supplies, miscellaneous, others

21. Total cash operating expenses (Lines 8 thru 20)

Other Cash Outflows

22. Capital purchases

23. Family living

24. Other withdrawls and income taxes

25. Intermediate loan principal payments

26. Intermediate loan interest payments

27. Long-term loan principal payments

28. Long-term loan interest payments

29. Total cash outflow (Lines 21+22 thru 28)

Cash Flow Summary

30. Beginning cash balance

31. Inflows - outflows (Lines 7-29)

32. Cash position (Lines 30+31)

33. New borrowing: operation

34. New borrowing: intermediate

35. New borrowing: long-term

36. Operating loan principal payments

37. Operating loan interest payments

38. Ending cash balance (Lines 32+33+34+35-36-37)

Loan Balances End of Period

39. Operating (previous period line 39+33-36)

40. Intermediate (previous period line 40+34-25)

41. Long-term (previous period line 41+35-27)

11

12

wives are taking an active role in the farm

business operation, thus giving additional flex-

ibility in deciding who can work off the farm.

Carefully consider any additional expenses

related to off-farm employment such as

transportation, clothing, and child care.

Refinancing. Cash flow problems are

sometimes caused by a poor balance of

short-, intermediate-, and long-term debts

on the farm. Some farmers use short-term

loans to finance intermediate- and long-term

assets. Normally, operating loans are used to

purchase variable inputs such as seed, feed,

fertilizer, and chemicals. The loans are then

paid back as the commodities are sold.

However, don’t use operating loans for

intermediate- or long-term assets such as

equipment, breeding livestock, buildings, and

land because the receipts from one production

period cannot be expected to cover the costs

of assets that last for several production

periods. The idea of self-liquidating loans

suggests that a proper financing program

for loans would match the input’s life and

pattern of earnings with the length of repay-

ment schedule on the loan used to obtain the

input. A farm implement that will last 5 to

7 years should be financed for 5 to 7 years.

Financing it for a shorter period may cause

you cash flow problems.

If a drought year results in insufficient

receipts to cover the operating loan, rolling

this loan over to the next year may cause

cash flow problems. Perhaps you should

refinance the loan over a longer period so the

cash shortfall can be absorbed over several

production periods.

Refinancing can effectively deal with cash

flow problems but sometimes it may just be

buying time for you. If the farm is not

profitable, refinancing is an indication that

the problem is just being prolonged.

Liquidating assets. Selling your assets is

usually a more drastic measure for dealing

with cash flow problems; however, it may

be justified. Sell unprofitable assets first.

Excessive personal assets (boats, campers) and

other assets such as timber, replacement stock,

unused machinery, and unproductive land are

good candidates. Then consider downsizing

the operation through selling off breeding

livestock, machinery, and land, but only after

doing an in-depth long-term financial analysis

of the impact of these corrective actions.

When selling assets, do not overlook the

income tax consequences of capital gains.

Also, do not sell assets without discussing it

with creditors who have an interest in those

assets.

Maintaining credit reserves. Manage debt

to maintain a credit reserve. If you borrow to

the limit and other cash inflows stop, then

your liquidity reserve will dry up also. Bills

will accumulate and creditors will line up at

your door. When you’re experiencing cash

flow problems, let your creditors know what

you are doing to solve the problems. Avoiding

creditors may just aggravate the problem.

Can Computer Software Help

with Farm Management?

The financial management of a farm is

complex and time consuming. You need

time to gather and organize data and for-

mulate cash flow statements. Computer

software is available that can be a big help

to you. Maryland Cooperative Extension

offers farmers computer assistance for cash

flow planning through the FINPACK farm

financial planning and analysis program.

This program, developed by the University of

Minnesota, does a complete financial analysis

of your farm in addition to cash flow

planning. It has been used on over 40,000

farms in 40 states. The FINFLO and FINTRAN

components of this program provide a

comprehensive cash flow analysis of the farm

operation. To find out more about this

program, see your Extension agent at your

local county Extension office.

P1998

Assessing and Improving Farm Cash Flow

by

Dale M. Johnson

Extension Economist

Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics

Billy V. Lessley

Professor

Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics

James C. Hanson

Associate professor

Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics

Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, University of Maryland, College Park,

and local governments. Bruce L. Gardner, Interim Director of Maryland Cooperative Extension, University of Maryland.

The University of Maryland is equal opportunity. The University’s policies, programs, and activities are in conformance with pertinent Federal and State laws and regulations on nondiscrimi-

nation regarding race, color, religion, age, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, marital or parental status, or disability. Inquiries regarding compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended; Title IX of the Educational Amendments; Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973; and the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990; or related legal requirements

should be directed to the Director of Human Resources Management, Office of the Dean, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Symons Hall, College Park, MD 20742.