This report is the product of the Allergy and Asthma Task Force

that was convened and supported by Thermo Fisher Scientific.

More information available at

allergyaidiagnostics.com

The Allergy and Asthma Task

Force Recommendations

The Practical Application of Allergic Trigger

Management to Improve Asthma Outcomes

The Need to Improve Outcomes for

People with Asthma in Primary Care and

Health Systems: Beyond Adding More

Pharmacotherapy

Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP, for the Allergy and

Asthma Task Force Members

S3

The Practical Application of Allergic Trigger

Management to Improve Asthma Outcomes

Step 1: Identify Patients with Allergic

Components of Asthma

Andrew Liu, MD; Allan Luskin, MD; Randall Brown, MD,

MPH, AE-C; Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH; Ivor Emanuel,

MD; Len Fromer, MD, FAAFFP; Christine W. Wagner, APRN,

MSN, AE-C; Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP

S5

Integrating Allergic Trigger Management

into Primary Care Asthma Management:

Step 3: A Significant Opportunity for Payers

and Health Systems

Randall Brown, MD, MPH, AE-C; Suzanne Madison, PhD;

Len Fromer, MD, FAAFP; Brad Lucas, MD; Steve Clark;

Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH; Christine W. Wagner, APRN,

MSN, AE-C; Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP

S25

The Practical Application of Allergic Trigger

Management to Improve Asthma Outcomes:

Step 2: Identifying and Addressing Allergen

Exposure in Daily Practice

Christine W. Wagner, APRN, MSN, AE-C; Allan Luskin, MD;

Len Fromer, MD, FAAFP; Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP;

Randall Brown, MD, MPH; Andrew Liu, MD

S14

Recommendations to Improve Asthma

Outcomes: Work Group Call to Action

Regulatory approval code: 63679.AL.US1.EN.v1.18.

allergyinsider

AUGUST 2018

Randall Brown MD, MPH, AE-C is the Director of Asthma Programs,

Center for Managing Chronic Disease, and a Clinical Assistant Pro-

fessor, Health Behavior and Health Education at the University of

Michigan. He is Co-Director, National Asthma Educator Certication

Board and leader of PACE programs internationally.

Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH is a Professor of Pediatrics, Epide-

miology and Biostatistics, as well as a member of the core faculty at

the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University

of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Dr. Cabana has maintained an

active presence in clinical medicine, serving as Chief of the UCSF

Division of General Pediatrics since 2005. Dr. Cabana has extensive

experience in practice-based research and has collaborated with

over 120 pediatric practices in several national randomized con-

trolled trials focused on primary care management of asthma.

Steve Clark, Sr. VP, Optum Life Sciences, has 20 years of experience

helping pharmaceutical and medical device companies in market-

ing, clinical, and reimbursement areas. He has worked with numer-

ous early-stage technologies to assess reimbursement issues and

develop strategies for assessment of market differentiation opportu-

nities. The work has included stakeholder analysis for payers, clini-

cians, and health policy analysts, as well as horizon scanning assess-

ments for market opportunity and comparative analysis.

Ivor Emanuel, MD served as a Clinical Assistant Professor in Oto-

laryngology at the University of California, San Francisco, and was

also on the clinical faculty in the Department of Otolaryngology at

Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. Dr Emanuel is a Fellow and

Past President of the AAOA. He is a Fellow of the American Acad-

emy of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery and a Member of

the ACAAI.

Len Fromer, MD, FAAFP, Executive Medical Director, Group Practice

Forum leads a team engaged in national projects with health systems

and group practices that deliver education, tools, and services to

achieve success in their clinical integration efforts. Dr. Fromer lectures

extensively on the topics of health-system reform, the patient centered

medical home and the accountable care organization. Dr. Fromer is

a Fellow of the AAFP, and a diplomat of both the American Board of

Family Practice and the National Board of Medical Examiners.

Andrew Liu, MD is a Pediatric Allergist, Director, Airway Inam-

mation Research & the Environment (AIRE) Program, Co-Director,

Asthma Clinical Research Center, The Breathing Institute, Section

of Pulmonary Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Professor,

Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine,

Adjunct Professor, Department of Pediatrics, National Jewish Health.

Alan Luskin, MD is Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine at Uni-

versity of Wisconsin and Director of the Center for Respiratory Health

at SSMHealth, President of HealthyAirways, an outcomes manage-

ment consulting group with research focusing on outcomes manage-

ment in airways diseases. He received the NIH Exemplary Service

Award for his work with the NAEPP formulating and disseminating

the National Asthma Guidelines. He is a Past Vice-President and

Distinguished Fellow of the ACAAI and received its Distinguished

Service Award.

Brad Lucas MD, MBA, FACOG is the Senior Medical Director for

Buckeye Health Plan, a subsidiary of Centene Corporation. Centene

manages care for 11 million members across 24 states. Dr. Lucas

has helped build and guide Centene’s award winning programs Start

Smart for Your Baby®, its Addiction in Pregnancy Program and pre-

term birth prevention programs. Similarly, he is responsible for the

development and implementation of programs that improve clinical

outcomes and ensure high quality care across all medical conditions

for Buckeye members. He continues to see patients at AxessPointe

Community Health Center.

Suzanne Madison, PhD holds graduate degrees in public adminis-

tration (MPA) and public health (MPH), a doctorate in public health

(community health track), and a certicate in clinical trials from Har-

vard Medical School. She has been involved in research for the

past nine years, as a participant in a clinical trial, a senior research

associate, and graduate of the Harvard Medical School, Global Clini-

cal Scholars Research Training Program. She currently serves in a

patient advocacy role with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research

Institute (PCORI) as a member of the Patient Engagement Advisory

Panel (PEAP).

Christine Waldman Wagner APRN, MSN, AE-C has developed and

presented numerous programs for health professionals on multiple

topics including diagnosis and treatment of asthma and allergic dis-

eases, patient education, health literacy, and other related topics.

She is a founding member and rst president of the Association of

Asthma Educators and served on the rst National Asthma Educa-

tor Certication Board of Directors. She is also a trained facilitator

for Problem Based Learning and faculty associate at Texas Woman’s

University.

Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc FAAFP, is a family physician researcher

who currently focuses on respiratory diseases, specically COPD

screening/case nding and implementation of new tools to improve

asthma outcomes. She is/was a member of the International Pri-

mary Care Respiratory Group; EPR-3 science panel, editor in chief

of Respiratory Medicine Case Reviews and the COPD Foundation

Research Committee. She is retired from her position as the director

of research at the Olmsted Medical Center, is an Adjunct Professor

of Family and Community Health at the University of Minnesota and

serves as a consultant to multiple NIH and PCORI funded studies of

asthma and COPD.

[

AFFILIATIONS

]

S2

SEPTEMBER 2018

S3

AUGUST 2018

The Need to Improve Outcomes for People

with Asthma in Primary Care and Health

Systems: Beyond Adding More

Pharmacotherapy

Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP, for the Allergy and Asthma Task Force Members

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Yawn is a paid consultant and has an ongoing relationship with

Thermo Fisher Scientic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Task Force appreciates the editorial support provided

by Sarah Staples, whose work was nancially supported by

Thermo Fisher Scientic. The Task Force also acknowledges and

appreciates the important logistical support provided by Kevin H.

TenBrink and Gabriel Ortiz of Thermo Fisher Scientic.

is supplement is the product of the Allergy and Asthma Task

Force convened and supported by ermo Fisher Scientic.

e Task Force met in person and remotely over a period of

20 months to develop and publish its recommendations to

identify which patients with asthma are of highest priority for

allergy evaluation, how that evaluation could be done, and

how allergy evaluation can be incorporated into primary care.

e expertise in the Task Force includes: primary care

(family medicine and pediatrics); specialists in allergy and

pulmonology, nursing, respiratory therapy, asthma educa-

tion, laboratory medicine, and health systems design; and

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

What this supplement addresses:

• Asthma inammation and the role of aeroallergen sen-

sitization in asthma burden

• The groups of people with asthma who are most likely to

benet from evaluation for allergen sensitization

• A practical approach to identifying and caring for those

subpopulations who shoulder disproportionate allergy

and asthma risk and morbidity

• The 2 readily available methods to assess specic al-

lergen sensitization

• Ways to include allergen evaluation in daily primary care

practice

• Potential solutions for the common barriers to patient

education regarding trigger avoidance and management

• The role of health systems and payers and the busi-

ness case for supporting and integrating allergen evalu-

ation and trigger avoidance education in primary care

practices.

the perspectives of quality experts, medical directors, and

patients. Members’ travel expenses were covered by the spon-

sor, as was the editorial support of Sarah Staples.

Task Force members (in alphabetical order) are: Randall

Brown MD, MPH, AE-C; Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH; Steve

Clark; Ivor Emanuel, MD; Len Fromer, MD, FAAFP; Andrew

Liu, MD; Brad Lucas, MD; Allan Luskin, MD; Suzanne Madi-

son, PhD; and Christine W. Wagner, APRN, MSN, AE-C. Task

Force Chair is Barbara Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP.

A

sthma is a common and increasingly prevalent

chronic respiratory condition that aected 25 mil-

lion Americans in the United States in 2007.

1

Most

people with asthma receive their asthma care within pri-

mary care practices.

2

People with asthma and their families

continue to experience signicant asthma-related disease

burden, with over 10.5 million oce visits a year, most of

which are unscheduled and in primary care oces.

1,2

ese

visits often focus on dealing with acute symptoms or exac-

erbations, with little time and attention available for pre-

vention of the next exacerbation and the daily ongoing bur-

den of asthma symptoms.

Added to unscheduled oce visits, 3 of every 5 children

with asthma

3

and more than half of working adults with

asthma

4

have their life disrupted by the need to seek urgent

or emergency care for their asthma each year.

5

Asthma is

the reason for over 1.8 million emergency department (ED)

visits and more than 400,000 hospitalizations each year.

5

About 10% of people with asthma have severe asthma,

resulting in several urgent care and emergency care visits

and a high risk of asthma-related hospitalization, in addi-

tion to missed school, work and activity days.

6-8

Much of this burden is potentially preventable. How-

ever, several studies have demonstrated that this continu-

ing asthma burden is not simply a need to prescribe more

inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators.

9

Other factors

must be considered, including triggers, medication adher-

ence, and comorbid conditions.

10

Most people with asthma

S3

SEPTEMBER 2018

S4

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

INTRODUCTION

]

have hypersensitivity that includes “allergic” reactions to

environmental exposures. Such environmental exposures

are common, with over 90% of homes having at least 3 detect-

able common aeroallergens and 73% having 1 or more at an

elevated level.

11

e presence of an allergen in the home will

not trigger asthma symptoms or exacerbations in a person

without sensitization to that allergen. e study authors con-

rmed that in many sensitized people, the presence of com-

mon allergens at home is associated with increased asthma

burden.

ASTHMA IS NOT WELL-CONTROLLED FOR

MOST PRIMARY CARE PATIENTS

In a recent study of over 1200 family medicine patients with

asthma, 56% of children, 52% of adolescents, and 63% of

adults had uncontrolled asthma, with over 20% making 1 or

more visits to the ED or hospital in the previous 6 months.

12

Several studies conrm that most Americans with asthma

continue to have suboptimal control of symptoms, periodic

asthma exacerbations, or both.

7,13,14

Widely disseminated

asthma-treatment guidelines are available, along with a

variety of generally eective pharmacotherapies.

15,16

ose

guidelines highlight the need to supplement existing phar-

macotherapy with attention to triggers that include irritants

and allergens.

WHAT ARE NEXT STEPS IN DECREASING

ASTHMA BURDEN?

Asthma is a condition of hypersensitivity to common expo-

sures, associated with chronic airway inammation, hyper-

reactivity, congestion, and airow restriction. Whereas

symptoms come and go, inammation and hyperreactivity

of airways are chronic and may be associated with persistent

narrowing of the airways, even when the person “feels well.”

For most people with asthma, that inammation is triggered

or maintained by exposure to allergens to which they are

sensitized. It is the need to address the sensitization to those

allergens that is the basis for this supplement. l

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most recent data.

htm. Accessed 13 July 2018.

2. Kwong KYC, Eghrari-Sabet JS, Mendoza GR, et al. e benets of specic immuno-

globulin E testing in the primary care setting. Am Manage Care. 2011;17:S447-S459.

3. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. Indicators of Well-Being.

Washington, DC: Federal Interagency Forum; 2012.

4. Mazurek JM, Syamlal G. Prevalence of Asthma, Asthma Attacks, and Emergency

Department Visits for Asthma Among Working Adults - National Health Interview

Survey, 2011-2016. MMWR. 2018;67(13):377-386.

5. Fuhlbrigge A, Reed ML, Stempel DA, Ortega HO, Fanning K, Stanford RH. e sta-

tus of asthma control in the U.S. adult population. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009;30(5):

529-533.

6. Rank MA, Wollan P, Li JT, Yawn BP. Trigger recognition and management in poorly

controlled asthmatics. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(6):99-105.

7. Sullivan SD, Rasouliyan L, Russo PA, Kamath T, Chipps BE. Extent, patterns, and

burden of uncontrolled disease in severe or dicult-to-treat asthma. Allergy.

2007;62(2):126-133.

8. Yawn BP, Wechsler ME. Severe asthma and the primary care provider: identifying

patients and coordinating multidisciplinary care. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1479.

9. Papadopoulos NG, Arakawa H, Carlsen KH, et al. International consensus on (ICON)

pediatric asthma. Allergy. 2012;67(8):976-997.

10. Lommatzsch M, Virchow JC. Severe asthma: denition, diagnosis and treatment.

Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(50):847-855.

11. Salo PM, Wilkerson J, Rose KM, et al. Bedroom allergen exposures in US households.

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1870-1879.e1814.

12. Yawn BP, Rank MA, Cabana MD, Wollan PC, Juhn YJ. Adherence to asthma guide-

lines in children, tweens, and adults in primary care settings: a practice-based net-

work assessment. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2016;91(4):411-421.

13. Colice GL, Ostrom NK, Geller DE, et al. e CHOICE survey: high rates of persis-

tent and uncontrolled asthma in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.

2012;108(3):157-162.

14. Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Rank MA, Bertram SL, Juhn Y, Pace W. Use of asthma APGAR

tools in primary care practices: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med.

2018;16(2):100-110.

15. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP). Guidelines for the

Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3). https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-

pro/guidelines/current/asthma-guidelines/full-report. Accessed 31 May 2018.

16. GINA—Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Guidelines 2017. http://ginasthma.org.

Accessed 21 May 2018.

Regulatory approval code: 51981.AL.US1.EN.v1.18

S5

AUGUST 2018

The Practical Application of Allergic Trigger

Management to Improve Asthma Outcomes:

Step 1: Identify Patients with Allergic

Components of Asthma

Andrew Liu, MD; Allan Luskin, MD; Randall Brown, MD, MPH, AE-C; Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH; Ivor

Emanuel, MD; Len Fromer, MD, FAAFP; Christine W. Wagner, APRN, MSN, AE-C; Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc,

FAAFP

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Liu discloses that he is a consultant for Thermo Fisher

Scientic.

Dr. Luskin has no conicts to disclose.

Dr. Brown reports that he is on the Board of Directors for Allergy

and Asthma Network; an advisor and speaker for AstraZeneca; a

speaker for Circassia Pharmaceuticals plc; a speaker for Integrity

Continuing Education Inc.; an advisor for Novartis AG; a speaker for

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; and an advisor for Thermo Fisher

Scientic.

Dr. Cabana is on the Merck Speakers Bureau and consults with

Novartis AG, Genentech, Inc. and Thermo Fisher Scientic.

Dr. Emanuel has an ongoing relationship with Thermo Fisher

Scientic.

Dr. Fromer has been a consultant and speaker for Thermo Fisher

Scientic in the recent past.

Christine W. Wagner has an ongoing relationship with Thermo

Fisher Scientic.

Dr. Yawn is a paid consultant and has an ongoing relationship with

Thermo Fisher Scientic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Task Force appreciates the editorial support provided

by Sarah Staples, whose work was nancially supported by

Thermo Fisher Scientic. The Task Force also acknowledges and

appreciates the important logistical support provided by Kevin H.

TenBrink and Gabriel Ortiz of Thermo Fisher Scientic.

Kim thought back through her recent asthma visit. She had

mentioned her concern about “hay fever” and wondered if any-

thing else was triggering her asthma attacks. She completed

the intake sheet and circled some things she thought made her

asthma worse—but no one had commented on any of them. Did

she have allergies? And were they making her asthma worse?

Her asthma was certainly causing problems, including missing

sleep and work, and interfering with her ability to care for her

children and family. What should she do next?

K

im’s experience is not unusual. Although widely

disseminated asthma-treatment guidelines are

available, along with a variety of eective pharma-

cotherapies, most patients with asthma continue to have

symptoms. Across all types of practices, almost half of adults

with asthma (47%) report very poorly controlled asthma

and another 24% report not well-controlled asthma.

1

Simi-

larly, the prevalence of uncontrolled asthma in children

with asthma in all practices is 46%.

2

In primary care prac-

tices, 63% of adults, 52% of adolescents, and 56% of children

with asthma have inadequate asthma control.

3

Most people

with asthma receive their care in a primary care setting, and

most continue to have suboptimal control of symptoms and

exacerbations.

3-7

National and international guidelines strongly support

the importance of evaluating and addressing environmental

triggers that can make asthma worse and cause exacerba-

tions.

8,9

e 2007 National Asthma Education and Preven-

tion Program (NAEPP) US guidelines recommend evaluating

the potential role of allergens, particularly indoor inhalant

allergens.

8

is recommendation is considered “Evidence

Category A” (ie, strong evidence from randomized controlled

trials with a rich body of supportive data).

8

Since publication

of these guidelines, additional compelling evidence has been

published on the importance of recognizing and treating the

allergic components of asthma.

10,11

Given the importance of allergens to asthma

morbidity and asthma management, patients

with persistent asthma should be evaluated

for the role of allergens as possible contributing

factors. —NAEPP. GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND

MANAGEMENT OF ASTHMA (EPR-3)

8

S5

SEPTEMBER 2018

S6

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

ASTHMA AND INFLAMMATION

Asthma is a condition of hypersensitivity to common expo-

sures, associated with chronic airway inammation, bron-

chial hyperreactivity with increased mucus, and airway

edema, obstruction, and narrowing. Symptom frequency

and severity are variable, but the underlying inammation

and hyperreactivity of the airways are chronic and present

even when a person “feels well.” Over time, these symptoms

may be associated with persistent narrowing and remodel-

ing of the airways (FIGURE 1

12

).

Sensitization

More than 80% of children and adolescents and 60% of

adults

13,14

with asthma are sensitized to inhaled environ-

mental allergens. Among all ages, 70% of patients with

severe asthma are allergic.

15-17

ere is a direct and causal

relationship between allergic sensitization and asthma

control and exacerbations.

18

For most people with asthma,

hypersensitivity includes reactions to environmental expo-

sures. Liu and colleagues summarized multiple pathways

linked to asthma severity, including allergen sensitization

(FIGURE 2).

19

Long-term implications of inhaled

allergen sensitization and exposure

In children, allergy is also a risk factor for asthma persis-

tence (FIGURE 3

20

). Only 10% of children with nonaller-

gic asthma at age 5 years continue to have asthma by age

12 years. In contrast, approximately 50% of children

with allergic asthma continue to have symptoms at age

12 years.

20

Early sensitization to multiple inhalant aller-

gens

21-23

and sensitization combined with perennial expo-

sure in the home in early life

24

predict asthma persistence,

exacerbation, and lung dysfunction.

FIGURE 1 Airway remodeling caused by asthma-associated inammation

12

Normal Airway Asthmatic Airway

Triggers

Normal,

subclinical

response

Complete

Recovery

(Partial) recovery

Obstruction

Inflammation & Bronchial

Hyperresponsiveness

Remodeling

Hypertrophic smooth muscle

Collagen deposition

Thickened Basement Membrane

Mucus and

Cell debris

Edema

Bronchospasm

Reprinted from Papadopoulus, et al. International consensus on (ICON) pediatric asthma. Allergy. 2012;67(8):976-997. Used with permission.

S7

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

In sensitized children, adolescents, and adults, expo-

sure to allergic triggers is associated with an increase in

asthma symptoms, decreased lung function, and recur-

ring asthma exacerbations. In addition, those with multiple

inhaled allergen sensitizations are at increased risk of worse

control, often resulting in sick visits to the oce and visits

to urgent care and the emergency department (ED),

25

as

well as hospitalizations (FIGURE 4).

26

e number of asthma

triggers a patient has is associated with the risk of exacer-

bations, more severe exacerbations, and poorer quality

of life.

18

Although viral infection is a common trigger for asthma

exacerbations, especially in younger children, recent data

demonstrate that allergen sensitization results in a signi-

cant increased risk of asthma exacerbation when there is a

combination of allergen sensitization, exposure, and viral

infection (FIGURE 4

26

). e allergic phenotype of asthma

is associated with an impaired innate immune response

FIGURE 2 Pathways by which asthma risk factors contribute to asthma severity

19

Red arrows indicate how allergy acts through multiple pathways (allergen sensitization, allergic inammation, pulmonary physiology, and rhinitis

severity) to affect asthma severity. The negative effect of tobacco smoke exposure is partially mediated by pulmonary physiology (olive arrows).

Vitamin D is inversely associated with inammation (yellow arrow) but its overall effect on asthma severity is insignicant.

Reprinted from Liu et al. Pathways through which asthma risk factors contribute to asthma severity in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):1042-1050.

® 2016 with permission from Elsevier.

S8

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

to respiratory viral infection, mediated through immu-

noglobulin E (IgE). e link between viral infections and

allergen sensitization is conrmed by the decreased risk

of asthma exacerbation due to

viral upper respiratory infec-

tion (URI) when IgE-directed

therapy is prescribed for sensi-

tized or “allergic” children and

adolescents.

27,28

The role of serum IgE

Total IgE levels have been

used as an indicator of allergic

asthma. Although higher levels

of total serum IgE have been

associated with poorer asthma

outcomes

29,30

and higher health

care costs,

31

these levels are

variable, aected by genetics,

race, cigarette smoking, and

steroid use, and are, therefore,

not a reliable indicator of aller-

gen sensitization and not a sub-

stitute for specic IgE allergen

testing. Signicant allergy may

exist with low or “normal” total

IgE levels, and higher total IgE

levels may exist without any

signicant specic allergic sen-

sitization. Increasingly, overall

allergen sensitization is being

recognized as a major factor in

asthma across all age groups

and all levels of asthma sever-

ity.

32

Asthma phenotypes

Recent evidence demonstrates

that the common exacerbation-

prone phenotype in US inner

city children with asthma, rep-

resenting 16% of these children,

included sensitization to most

common inhalant allergens for

which they were tested (a mean

of 14 sensitizations from a 22-

allergen panel).

33

is indicates

that exacerbation-prone asth-

matic children are typically

highly allergic to their environ-

ment. In the Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma:

Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study, there

was a direct relationship between the number of allergens

Risk Factors

Odds Ratios

Sensitization, Exposure,

and Viral Infection

Sensitization and Viral Infection

Viral Infection

Sensitization and Exposure

Sensitization

1.8

2.6

3.2

8.9

19.4

FIGURE 4 Allergen sensitization, exposure, and viral infection greatly

increase the risk for asthma hospital admissions

26

The risk (odds ratio) of severe asthma exacerbations resulting in hospitalization increases across

groups of patients experiencing allergen sensitization, sensitization with exposure to allergen, viral

infection (upper respiratory infection), and combinations of these factors.

FIGURE 3 Children with persistent wheeze and inhalant allergies in

preschool life are more likely to develop persistent asthma

20

Approximately 50% of children with atopic asthma characterized by wheezing continue to have

symptoms at age 12 years. Early sensitization to multiple inhalant allergens and sensitization com-

bined with perennial exposure in the home in early life predict asthma persistence, exacerbation,

and lung dysfunction.

Reprinted from Liu & Martinez. Chapter 2: Natural History of Allergic Diseases and Asthma. In: Leung DYM, et al. (eds.).

Pediatric Allergy: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Inc.; 2016. ® 2016 with permission from Elsevier.

Atopy-Associated

Asthma

Transient Early

Wheezers

Wheezing Prevalence

Nonallergic

Wheezers

Asthma in Obese

Females with

Early-Onset Puberty

Age (years)

036912

S9

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

to which adults, adolescents,

and children were sensitized and

their rates of exacerbations, the

severity of those exacerbations,

and the person’s asthma-related

quality of life.

32

Zoratti and colleagues dis-

tinguished 5 potential asthma

phenotypes (A, B, C, D, and E)

in US inner city children, with

asthma severity burdens ranging

from minimal to high (

FIGURE 5).

33

Children with phenotypes C, D,

and E demonstrate progressively

greater allergen sensitization

and increasingly worse clinical

conditions, likely representing

classic T-helper type 2-driven

allergic asthma. ese allergic

phenotypes also represent 70%

of the study population and

exhibit striking parallel relation-

ships between allergic sensiti-

zation and indicators of asthma

severity. Compatible with

this picture of allergen-driven

asthma, phenotype A represents

the group with low sensitiza-

tion levels and low asthma bur-

den. Only phenotype B appears

to highlight other non-allergic

mechanisms of asthma that may

result in signicant asthma symptom burden.

THE PRIMARY CARE

CHALLENGE

ree-quarters of people with asthma receive care in a pri-

mary care practice.

34

ese people and their families con-

tinue to experience a signicant asthma-related disease

burden, with over 10.5 million oces visits, most of which

are unscheduled and in primary care oces, added to 1.8

million ED visits and more than 400,000 hospitalizations

annually.

12,35,36

ree of every 5 children and more than half

of adults with asthma have had their life disrupted by the

need to seek urgent or emergency care for their asthma

each year.

37

About 10% of people with asthma have severe

asthma, resulting in several urgent and emergency visits

and a high risk of asthma-related hospitalization, in addi-

tion to missed school, work, and activity days.

38,39

Several

studies have demonstrated that this continuing asthma

burden is not simply the basis for prescribing more asthma

medications; further evaluation should be undertaken.

Allergen avoidance and abatement (eg, environmen-

tal control), as well as allergy treatments such as immu-

notherapy (subcutaneous or sublingual), require identi-

cation of allergen sensitization. Particularly in children,

allergy avoidance and immunotherapy have improved

asthma control with decreased symptoms, decreased exac-

erbations, and decreased oral and inhaled corticosteroid(s)

use.

40

Yet allergy evaluation was only discussed in about

33% of primary care oce visits for asthma, and allergy test-

ing was only documented in 2% of cases of asthma over the

course of a year.

3

Several questionnaires to assess asthma

control are available (

FIGURE 6). A newly published study

is the rst to nd that introducing an asthma tool—the

Asthma APGAR Plus—into primary care practices improves

patient and practice outcomes.

7

e Asthma APGAR Plus is

the only tool that includes a brief patient query regarding aller-

FIGURE 5 Children with high asthma burden are highly allergic

to their environment

33

* For a full description of asthma medication steps, refer to pages 46–52 of the EPR–3 Summary Report 2007.

8

The higher the step number (from 1 to 6), the more intense the medication regimen.

Reprinted from Zoratti, et al. Asthma phenotypes in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):1016-1029.

® 2016 with permission from Elsevier.

Asthma Phenotypes (N=616)

A (15%) B (15%) C (24%) D (30%) E (16%)

Asthma symptoms Minimal High Minimal Minimal Highest

Lung function/

impairment

Normal Mild Minimal Intermediate Most

Allergen

sensitization (no.

of positive tests in

22-allergen panel)

1 2 9 13 14

Step in asthma

medication plan*

1.39 4.2 1.93 3.4 4.7

Rhinitis symptom

severity

Minimal Intermediate Minimal High High

S10

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

FIGURE 6 Assessment tools for asthma symptom control

APGAR, Activities, Persistent, triGGers, Asthma medications, Response to therapy.

1. Nathan RA, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):59-65.

2. Juniper EF, et al. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(4):902-907.

3. Vollmer WM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5 Pt 1):1647-1652.

4. Yawn BP, et al. J Asthma Allergy. 2008;31(1):1-10.

Available Assessment Tools to

Evaluate Asthma Symptom Control

Asthma Control Test

(ACT)

1

Asthma Therapy

Assessment

Questionaire (ATAQ)

3

Asthma Control

Questionaire (ACQ)

2

Asthma APGAR Plus

4

gies and triggers, designed to facilitate discussion of allergens

and need for further allergy evaluation with patients. Using

a tool to assess potential “allergies” is the rst step in allergy

evaluation, which often requires investigation and care over

a number of visits, an important hallmark of the continuity of

primary care.

WHO SHOULD BE TESTED FOR INHALANT

ALLERGEN SENSITIZATION?

All patients who have been given a diagnosis of persis-

tent asthma should be evaluated to identify their allergic

triggers. But this recommendation is not typically imple-

mented in the primary care setting, where there are con-

cerns about limited time, cost, and patient burden. A more

practical approach is to identify the specic patient groups

most likely to benet from evaluation of the potential

allergic contribution to asthma burden (FIGURE 7).

1. Patients of any age who continue to have high

asthma burden or high risk despite treatment.

a. A severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization

b. Two or more ED asthma visits a year resulting in

treatment with systemic corticosteroids, such as

prednisone and dexamethasone

c. Prescribed step-4 or step-5 asthma treatment, which

includes high-dose ICS

d. ose whose primary care clinician may con-

sider them a potential candidate for biologic

therapy but who have not yet had an allergy

evaluation.

In this high-burden/high-risk asthma group, diag-

nostic testing for inhalant allergen sensitization can help

identify people with high-risk asthma who are highly aller-

gic; identify specic allergen exposures that can underlie

their high asthma burden; and identify those who may

benet from specic asthma therapies to reduce their

asthma burden, lower the risk of future exacerbation, limit

the risk of side eects from high-dose ICS, and limit the

morbidity and mortality of future exacerbations and the

side-eects of“bursts” of oral corticosteroids (OCS) used

to treat them.

S11

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

2. Young children with recurrent cough/wheeze

symptoms to help predict their likelihood of

persistence of “asthma” beyond age 6 years.

Inhalant allergen sensitization, atopic dermatitis, aller-

gic rhinitis, and parental asthma are key risk factors to

predict which preschoolers with recurrent respiratory

symptoms, such as cough and wheeze, are most likely to

develop persistent asthma. Allergen sensitization can-

not be adequately assessed by history and physical exam

alone. Diagnosing specic inhalant allergen sensitizations

in at-risk children identies those who are most likely to

develop persistent asthma and allows opportunities for

designing allergen-avoidance strategies that may improve

outcomes.

3. Patients of any age meeting any of the asthma Rules

of Two

®

* criteria while on daily controller or

maintenance therapy.

a. Having >2 days/week of asthma symptoms or quick

relief inhaler use

b. Having >2 nights/month of nighttime asthma

symptoms

c. Having ≥2 asthma exacerbations/year resulting in a

burst of OCS

d. Requiring >2 rescue albuterol inhaler lls/rells a

year not when used just to cover dierent sites such

as home/school/daycare/oce.

*Registered trademark of Baylor Health Care System. Adapted

from: Millard et al. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2014;27(2):79-82.

e presence of daytime and/or nighttime symptoms and/

or the need for additional medication prompts the need

for additional management. Diagnostic testing for inhalant

allergen sensitization can identify specic allergen expo-

sures that, when treated, may allow a step-down in high-

dosage ICS therapy and may identify patients with asthma

who may benet from specic asthma therapies to reduce

their asthma burden and risk of future exacerbations.

CHANGING PRACTICE

When exacerbations or out-of-control symptoms are recog-

nized, a common approach is to simply add more medica-

tions, which is often expensive and ineective.

4

Before con-

sidering any additional therapy, it is important that patients

are receiving the prescribed therapy at the target site. High

asthma burden is not necessarily a deciency of prescribed

pharmacotherapy. Two issues should always be addressed

before adding more inhalers:

• Is the patient taking the medications?

• Are the medications getting into the lungs?

Rules of Two

®

is a registered trademark ofBaylorHealth Care System. Adapted from: Millard et al. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2014;27(2):79-82.

FIGURE 7 Patients in need of an allergy evaluation

Patients of any age experiencing a high asthma burden or

high risk despite treatment

• An asthma-related hospitalization or 2 or more emergency department visits

• Step 4 or higher medication regimen

• Potential candidate for biologics

Young children with recurrent cough/wheeze symptoms to help

predict the likelihood of asthma persistence beyond 6 years.

Patients of any age meeting the asthma "Rules of 2" criteria

while on therapy

• >2 days/week of symptoms or quick relief inhaler use

• >2 nights/month of nighttime asthma symptoms

• ≥2 asthma exacerbations/year (episodes resulting in a burst of oral steroids) or >2 rescue

albuterol inhaler lls/rells per year

S12

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

Nonadherence is a common problem that we discuss

in the next article. Inadequate inhaler technique is also

common and must be addressed by selecting inhaler or

drug delivery devices tailored to the patient’s age and capa-

bilities.

3,41

After selecting the appropriate device, teaching,

observing, and reassessing proper inhaler technique regu-

larly can enhance drug delivery and improve unintentional

nonadherence, decreasing symptom and exacerbation

burden.

For many people with asthma, addressing adher-

ence and inhaler technique fails to mitigate the underly-

ing cause of bronchial hyperreactivity: the inammatory

response to allergic triggers. Identication of allergens to

which the patient is sensitized and attempts to decrease

allergen impact are also needed.

3

NAEPP guidelines

8

and

the NAEPP Guideline Implementation Panel

42

recommend

determining the patient’s exposure to allergens, assessing

sensitization from the medical history and skin or in vitro

testing, and interpreting positive results in the context of the

patient’s medical history.

8

Accordingly, incorporating aller-

gen identication into routine asthma management is the

main goal of this supplement.

CONCLUSIONS

Assessing and dealing with asthma-related allergies can

help prevent airway remodeling, reduce children’s and

adolescents’ days of wheezing and asthma-related hospi-

talizations, and, in adults, reduce the necessity for quick-

relief medications and nighttime awakenings. Although all

people with asthma may be an appropriate candidate for

aeroallergen sensitization assessment, the groups with the

highest likelihood of benet are those with high asthma

burden, an uncertain asthma future, and uncontrolled

symptoms.

Kim came into the ofce after another visit to the ED last month,

where she was again given a diagnosis of “bronchitis,” given

oral corticosteroids plus antibiotics, and told to take her asthma

medications regularly. The pharmacy lled the prescriptions

from the ED, but told her that the usual asthma prescriptions

were too old to rell and her children’s prescriptions could not

be relled either, so she had no source of medication and is

wheezing and short of breath again.

Today, Kim’s Asthma APGAR score is 4—conrming her

out-of-control asthma. She circled several triggers, includ-

ing tobacco smoke, pets, and seasonal issues. She noted

her incomplete adherence, due primarily to cost and lack of a

current prescription for the asthma medications, and further

reported that her asthma medications were only “somewhat

helpful” even when used. Your diagnosis is difcult-to-control

asthma, due to issues of adherence and unidentied triggers

that have not been addressed. She asks you about allergies.

Kim and you agree to her continued use of daily moderate-

strength ICS, combined with a long-acting beta-agonist bron-

chodilator. Upon review of inhaler technique, the medical assis-

tant noted some errors that were corrected; nal observation

demonstrated adequate inhaler technique. Following discus-

sion of Kim’s suspected allergies and your expressed concerns

about the potential impact of allergies on her asthma symptoms

and exacerbations, she agrees to have the blood test for pos-

sible allergen sensitization but declines to visit an allergist at this

time, due to concerns about getting time off work and visiting

yet another physician. As Kim makes an appointment to return

to review the allergy test results, she comments to your recep-

tionist, “She is the rst doctor who has bothered to listen to me

about my asthma and allergies. I will give her another try.” l

REFERENCES

1. Murphy KR, Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Nathan RA, Stolo SW, Doherty DE. Asthma

management and control in the United States: results of the 2009 Asthma Insight

and Management survey. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(1):54-64.

2. Stanford RH, Gilsenan AW, Ziemiecki R, Zhou X, Lincourt WR, Ortega H. Predic-

tors of uncontrolled asthma in adult and pediatric patients: analysis of the Asth-

ma Control Characteristics and Prevalence Survey Studies (ACCESS). J Asthma.

2010;47(3):257-262.

3. Yawn BP, Rank MA, Cabana MD, Wollan PC, Juhn YJ. Adherence to asthma guide-

lines in children, tweens, and adults in primary care settings: a practice-based net-

work assessment. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2016;91(4):411-421.

4. Sullivan SD, Rasouliyan L, Russo PA, Kamath T, Chipps BE; TENOR Study Group.

Extent, patterns, and burden of uncontrolled disease in severe or dicult-to-treat

asthma. Allergy. 2007;62(2):126-133.

5. Fuhlbrigge A, Reed ML, Stempel DA, Ortega HO, Fanning K, Stanford RH. e

status of asthma control in the U.S. adult population. Allergy Asthma Proc.

2009;30(5):529-533.

6. Colice GL, Ostrom NK, Geller DE, et al. e CHOICE survey: high rates of persis-

tent and uncontrolled asthma in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.

2012;108(3):157-162.

7. Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Rank MA, Bertram SL, Juhn Y, Pace W. Use of asthma APGAR

tools in primary care practices: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam

Med. 2018;16(2):100-110.

8. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP). Guidelines for the

diagnosis and management of asthma (EPR-3). www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/

guidelines/current/asthma-guidelines/full-report. Accessed June 28, 2018.

9. Global Initiative for Asthma. Pocket guide for asthma management and preven-

tion. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/wms-Main-pocket-

guide_2017.pdf

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Topic: Asthma. www.ahrq.

gov/topics/asthma.html. Accessed June 28, 2018.

11. European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. AIT guidelines. www.eaa-

ci.org/resources/guidelines/ait-guidelines-part-2.html. Accessed June 28, 2018.

12. Papadopoulos NG, Arakawa H, Carlsen KH, et al. International consensus on

(ICON) pediatric asthma. Allergy. 2012;67(8):976-997.

13. Busse PJ, Cohn RD, Salo PM, Zeldin DC. Characteristics of allergic sensitization

among asthmatic adults older than 55 years: results from the National Health

and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2006. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.

2013;110(4):247-252.

14. Høst A, Halken S. e role of allergy in childhood asthma. Allergy. 2000;55(7):

600-608.

15. Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular ap-

proaches. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):716-725.

16. Arbes SJ Jr., Gergen PJ, Vaughn B, Zeldin DC. Asthma cases attributable to atopy:

results from the ird National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1139-1145.

17. Moore WC, Bleecker ER, Curran-Everett D, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood

Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. Characterization of the severe asth-

ma phenotype by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma

Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(2):405-413.

S13

SEPTEMBER 2018

[STEP 1:

ALLERGIC COMPONENTS OF ASTHMA

]

18. Luskin AT, Chipps BE, Rasouliyan L, Miller DP, Haselkorn T, Dorenbaum A. Im-

pact of asthma exacerbations and asthma triggers on asthma-related quality of life

in patients with severe or dicult-to-treat asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract.

2014;2(5):544-552.e1-e2.

19. Liu AH, Babineau DC, Krouse RZ, et al. Pathways through which asthma risk fac-

tors contribute to asthma severity in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2016;138(4):1042-1050.

20. Liu AH, Martinez FD. Chapter 2: Natural history of allergic diseases and asthma.

In: Leung DYM, ed. Pediatric Allergy: Principles and Practice. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA:

Elsevier, Inc.; 2016:

21. Simpson A, Tan VY, Winn J, et al. Beyond atopy: multiple patterns of sensitiza-

tion in relation to asthma in a birth cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

2010;181(11):1200-1206.

22. Belgrave DC, Buchan I, Bishop C, Lowe L, Simpson A, Custovic A. Trajecto-

ries of lung function during childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(9):

1101-1109.

23. Havstad S, Johnson CC, Kim H, et al. Atopic phenotypes identied with latent class

analyses at age 2 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):722-727.e2.

24. Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Niggemann B, Gruber C, Wahn U; Multicentre Allergy

Study (MAS) group. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asth-

ma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):763-770.

25. Butz A, Morphew T, Lewis-Land C, et al. Factors associated with poor controller

medication use in children with high asthma emergency department use. Ann Al-

lergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(4):419-426.

26. Murray CS, Poletti G, Kebadze T, et al. Study of modiable risk factors for asthma

exacerbations: virus infection and allergen exposure increase the risk of asthma

hospital admissions in children. orax. 2006;61(5):376-382.

27. Teach SJ, Gill MA, Togias A, et al. Preseasonal treatment with either omalizumab or

an inhaled corticosteroid boost to prevent fall asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 2015;136(6):1476-1485.

28. Gill MA, Liu AH, Calatroni A, et al. Enhanced plasmacytoid dendritic cell antiviral

responses after omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1735-1743.e9.

29. Burrows B, Martinez FD, Halonen M, Barbee RA, Cline MG. Association of

asthma with serum IgE levels and skin-test reactivity to allergens. N Engl J Med.

1989;320:271-277.

30. Borish L, Chipps B, Deniz Y, Gujrathi S, Zheng B, Dolan CM; TENOR Study Group.

Total serum IgE levels in a large cohort of patients with severe or dicult-to-treat

asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95(3):247-253.

31. Luskin AT, Antonova E, Broder M, Chang E, Omachi TA. Higher immunoglobulin E

(IgE) levels are associated with greater emergency care and other healthcare utili-

zation among asthma patients in a real-world data setting. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2016;137(2 Suppl):AB9.

32. Chipps BE, Zeiger RS, Borish O, et al; TENOR Study Group. Key ndings and clini-

cal implications from e Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: Outcomes

and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):

332-342.e10.

33. Zoratti EM, Krouse RZ, Babineau DC, et al. Asthma phenotypes in inner-city chil-

dren. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):1016-1029.

34. Kwong KYC, Eghrari-Sabet JS, Mendoza GR, et al. e benets of specic im-

munoglobulin E testing in the primary care setting. Am Manage Care. 2011;17:

S447-S459.

35. Asthma. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; March 31, 2017. www.cdc.

gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm. Accessed June 28, 2018.

36. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children in

brief: Key national indicators of well-being, 2012. Washington, DC: US Govern-

ment Printing Oce. www.childstats.gov/pdf/ac2012/ac_12.pdf. Accessed June

28, 2018.

37. Most recent asthma data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; May 15,

2018. www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm. Accessed June 28, 2018.

38. Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Dalal AA, et al. Utilization and costs of severe uncon-

trolled asthma in a managed-care setting. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;4(1):

120-129.e3.

39. Chipps BE, Haselkorn T, Rosén K, Mink DR, Trzaskoma BL, Luskin AT. Asthma ex-

acerbations and triggers in children in TENOR: impact on quality of life. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 2018;6(1):169-176.e2.

40. Lin SY, Azar A, Suarez-Cuervo C, et al. e Role of Immunotherapy in the Treat-

ment of Asthma. Comparative Eectiveness Review No. 196 (Prepared by the Johns

Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No.290-2015-

00006-I). AHRQ Publication No. 17(18)-EHC029-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2018. https://eectivehealthcare.ahrq.

gov/sites/default/les/pdf/cer-196-full-immunotherapy-asthma.pdf. Accessed

June 28, 2018.

41. Price DB, Roman-Rodriguez M, McQueen RB, et al. Inhaler errors in the CRITIKAL

study: type, frequency, and association with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Im-

munol. 2017;5(4):1071-1081.e9.

42. National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Guidelines

implementation panel report for: Expert Panel Report 3—guidelines for the diagnosis and

management of asthma: Partners putting guidelines into action. Bethesda, MD: US De-

partment of Health and Human Services ; 2008 Dec. NIH Publication Number 09-6147.

www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/gip_rpt.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2018.

Regulatory approval code: 52044.AL.US1.EN.v1.18

AUGUST 2018

The Practical Application of Allergic Trigger

Management to Improve Asthma Outcomes:

Step 2: Identifying and Addressing Allergen

Exposure in Daily Practice

Christine W. Wagner, APRN, MSN, AE-C; Allan Luskin, MD; Len Fromer, MD, FAAFP;

Barbara P. Yawn, MD, MSc, FAAFP; Randall Brown, MD, MPH; Andrew Liu, MD

DISCLOSURES

Christine W. Wagner has an ongoing relationship with Thermo

Fisher Scientic.

Dr. Luskin has no conicts to disclose.

Dr. Fromer has been a consultant and speaker for Thermo Fisher

Scientic in the recent past.

Dr. Yawn is a paid consultant and has an ongoing relationship with

Thermo Fisher Scientic.

Dr. Brown reports that he is on the Board of Directors for Allergy

and Asthma Network; an advisor and speaker for AstraZeneca; a

speaker for Circassia Pharmaceuticals plc; a speaker for Integrity

Continuing Education Inc.; an advisor for Novartis AG; a speaker

for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; and an advisor for Thermo

Fisher Scientic.

Dr. Liu discloses that he is a consultant for Thermo Fisher

Scientic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Task Force appreciates the editorial support provided

by Sarah Staples, whose work was nancially supported by

Thermo Fisher Scientic. The Task Force also acknowledges and

appreciates the important logistical support provided by Kevin H.

TenBrink and Gabriel Ortiz of Thermo Fisher Scientic.

I

n the previous article, we presented the rationale for

allergy testing as part of asthma care and made recom-

mendations for identifying patients with the greatest

need for allergy assessment, testing, and interventions. Next,

we present suggestions for prioritizing the allergens to be

assessed, tests that identify allergen sensitization, and treat-

ments, including avoidance, environmental control, phar-

macotherapy, and immunotherapy.

Maristela Nabong-Nillas, MD, Chief of Pediatrics at Little

River Medical Center, SC, speaks about asthma and allergy

evaluation from rsthand experience:

“When I moved here, I noticed that many patients—per-

haps one-third—had atopic problems, including allergy and

asthma. During my career, asthma care has unfolded, from

simply treating acute exacerbations that required hospital-

ization to allowing management for most asthma on an out-

patient basis.

“Improving outcomes for patients with asthma requires

a multicomponent coordinated effort. We were fortunate

to be a part of The QTIP project (Quality Through Technol-

ogy and Innovations in Pediatrics), a Federal CHIPRA (Chil-

dren’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act) Qual-

ity Improvement grant in 2011 to address quality measures,

including asthma management. We developed system-wide

methods to identify people with persistent asthma using daily

controller medication to see if they had asthma action plans,

and had received evaluation for environmental triggers.

“Initially, we asked parents about suspected triggers and

used their responses. At the time, trigger testing required

referral to an allergist. Many of our patients did not want

to or could not take this step. Now, we identify triggers

based on blood work (specic immunoglobulin E [sIgE]

testing). Parents are interested in knowing about trig-

gers and like not having skin testing. Patients return after

2 weeks to discuss results. Positive results are followed up

with face-to-face education and handouts explaining how

to reduce exposure.

“If parents learn that environmental measures will help avoid

triggers, they are open to testing. They’re the ones who are

up at night and they’re appreciative if they know what to

avoid. Negative results let us focus on nonallergic causes for

symptoms. I have not had to admit any patients with asthma

for the past 3 years because their asthma symptoms are

being controlled.”

COMMON TRIGGERS/ALLERGENS AND

EFFECTIVE CONTROL MEASURES

ere is strong evidence that exposing patients with asthma

S14

SEPTEMBER 2018

S15

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

STEP 2: ALLERGEN EXPOSURE IN DAILY PRACTICE

]

who are sensitized to certain indoor and outdoor aeroaller-

gens increases symptoms in those with high asthma burden,

resulting in frequent exacerbations.

1,2

Identifying sensitiza-

tion to specic aeroallergens is required to guide appropri-

ate targeted exposure control. e plan for environmental

control is often complicated by the frequent presence of

multi-sensitization, requiring multiple control measures.

e National Asthma Education and Prevention Program

(NAEPP) guidelines recommend using allergy testing to

educate patients about the role of allergens in their disease

and to delineate specic environmental control measures for

sensitized patients experiencing symptoms.

3

Relevance of identifying common allergens

Of all the relevant indoor antigens, house dust mite is the

most common. ere are very few locations in the United

States in which house dust mites are not of concern. Only

high altitude (>3,000 feet above sea level) protects against

dust mites. Exposure to cockroaches and rodents is also

common in certain areas of the United States—such as the

Southeast, where cockroaches survive and breed indoors

and outdoors. Rodent exposure may be more common in

inner-city and rural areas. Strong evidence links indoor

mouse allergen exposure in homes and schools to wors-

ened asthma symptoms in sensitized children.

4-6

Sensitiza-

tion to these indoor allergens is associated with increasing

asthma severity and more frequent and severe exacerba-

tions (FIGURE 1

7-9

). For school-age children in the Childhood

Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study, sensitization

and exposure to multiple allergens (mite, cat, dog, Alter-

naria fungi, and cockroach) made asthma worse. For US

inner-city children in the National Cooperative Inner-City

Asthma Study population, the most important indoor aller-

gens were cockroach and rat, and probably mice. Half of the

bedrooms of inner-city children had a high level of cock-

roach allergen.

7

Indoor allergen sensitization is known to be greater

among minority populations living in urban environments,

compared to non-Latino whites.

10,11

In particular, black and

Puerto Rican populations carry the highest risk of sensitiza-

tion to those allergens that are most associated with asthma

morbidity. African-American youth are more likely to have a

mouse and/or cockroach sensitization prole independently

associated with asthma exacerbations, acute care visits, and

hospitalizations, compared to non-Latino white youth. So

too, Puerto Rican and other Latino ethnic minorities are at

higher risk of mouse sensitization and attributable asthma

hospitalization compared to those of Mexican heritage.

10,11

is evidence highlights how a simple clinical risk strati-

cation and personalized approach may impact critical out-

comes among patients who shoulder disproportionate dis-

ease burden.

Although indoor allergens are of prime importance,

assessing sensitization to seasonal outdoor allergens can also

lead to improved outcomes. Associations exist between peak

seasonal pollen and fungi levels and emergency department

(ED) visits for asthma exacerbations.

12

Additionally, asthma

exacerbations can increase dramatically after thunderstorms

that expose sensitized patients to electrostatically fractured

pollen and fungi.

13

How will knowing sensitization affect my practice?

Is effective therapy available?

When a person has conrmed sensitization, a history

of symptoms, and a reaction compatible with exposure,

2 approaches can be considered:

• Trigger allergen reduction, which has demonstrated

ecacy, especially in children

FIGURE 1 Aeroallergen sensitization and exposure to common allergens and

asthma severity and exacerbations

7-9

Cat Dog Mold Alternaria Mice/Rat Cockroach

Prednisone

Bursts

8 8 8

Urgent Care

Visits

8 8 7,9 7,9

Hospitalizations 8 8 8 8 7,9 7,9

Blue arrows show that, for school-age children, sensitization and exposure to multiple allergens, such as mite, cat, dog, Alternaria, and

cockroach, made asthma worse when they occurred together. Green arrows show that, for US inner-city children, the most important

indoor allergens were cockroach and rat, and probably mice.

S16

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

STEP 2: ALLERGEN EXPOSURE IN DAILY PRACTICE

]

• Targeted immunotherapy, which is not available

for all allergens but is eective in both children and

adults.

Effective exposure control measures

ere is evidence that multifaceted environmental control

measures are eective in reducing the burden of asthma,

but no specic combination of interventions has proved

more eective than others

14

(TABLE 1

15-20

). is evidence

strengthens the imperative to correctly and accurately

identify individual allergic sensitization so that appropriate

allergen control measures can be initiated.

Patients with asthma who have allergy testing are signi-

cantly more likely to employ preventive strategies (an asthma

plan, trigger avoidance, and medication adherence) and had

fewer days with allergy symptoms than patients who had not

been tested.

21

ese outcomes were supported by a study of

adults with moderately severe asthma,

22

who had an individ-

ualized plan, including environmental control based on the

results of allergy testing (FIGURE 2

22

).

What therapies are available?

e immunoglobulin E (IgE)-directed therapies include envi-

ronmental control, immunotherapy, and anti-IgE therapy

(omalizumab). Environmental control is the initial therapy;

particularly in children, simple changes have demonstrated

eectiveness.

A recent meta-analysis funded by the Agency for Health

Research and Quality (AHRQ) supports the value of identify-

ing allergen sensitization to guide potential immunotherapy,

23

which may play an increasing role in allergy and asthma man-

agement with the availability of US Food and Drug Adminis-

tration-approved sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for pol-

len and dust mite allergy. SLIT therapy is easy to administer,

has few potential risks, and can be done within primary care

practice. SLIT improves asthma symptoms, quality of life

(QoL), and FEV

1

, and reduces the use of long-term control

medications. It may also reduce the use of quick-relief medi-

cations. Local reactions to SLIT are common but only infre-

quently require a change in therapy. Systemic reactions are

so uncommon that home administration is recommended,

making this therapy convenient.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) reduces use of

long-term control medications and may also improve QoL

and lung function (eg, FEV

1

) and reduce the use of short-

acting bronchodilators and systemic corticosteroids. SCIT

oers more antigens but its use is limited by the need for

oce administration with monitoring, due to the potential

for systemic,potentially severe, reactions.

23

IDENTIFICATION OF

ALLERGIC SENSITIZATION

e diagnosis of clinically signicant sensitization requires

both history and testing conrmation.

24

e gold standard

for allergy diagnosis is the rarely used allergen exposure

challenge. While allergy evaluation begins with a history,

even with a structured history, allergy can be dicult to

diagnose accurately. A structured allergy history alone can

result in false-positives for perennial and seasonal allergens,

as outlined in FIGURE 3.

25

Combining history with diagnostic

Study Results

Parikh (2018)

15

For children with asthma hospital admissions, post-discharge referral for environmental mitigation

programs, as part of comprehensive discharge education, helped reduce the hospital readmission rate.

Murray (2017)

16

In children with asthma, a year-long study of dust mite-impermeable bed covers found a signicant

reduction in severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization, but no difference in exacerbations.

Rabito (2017)

17

In homes of children with asthma, a simple cockroach-specic intervention with insecticide bait

reduced asthma severity (eg, symptom burden), and modestly affected exacerbations.

Kercsmar (2006)

18

In children with asthma, home remediation of dampness and mold demonstrated a signicant reduction

in exacerbations.

Shirai (2005)

19

For people of all ages, a small (N=20) study of pet removal from homes of pet-allergic people with

asthma demonstrated signicant improvement, largely attributable to reduction in pet rodent or ferret

exposure, not exposure to cats or dogs.

Morgan (2004)

20

In inner-city children with asthma who were cockroach-sensitized, a multifaceted intervention, including

establishing an environmentally safe sleeping zone, signicantly reduced cockroach, dust mite, and

cat allergen exposures; signicantly reduced asthma symptom days and nights; and decreased missed

school days, emergency department visits, and unscheduled ofce visits. Signicantly reduced asthma

symptoms continued during the year after the study ended.

TABLE 1 Studies supporting environmental control measures

15-20

S17

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

STEP 2: ALLERGEN EXPOSURE IN DAILY PRACTICE

]

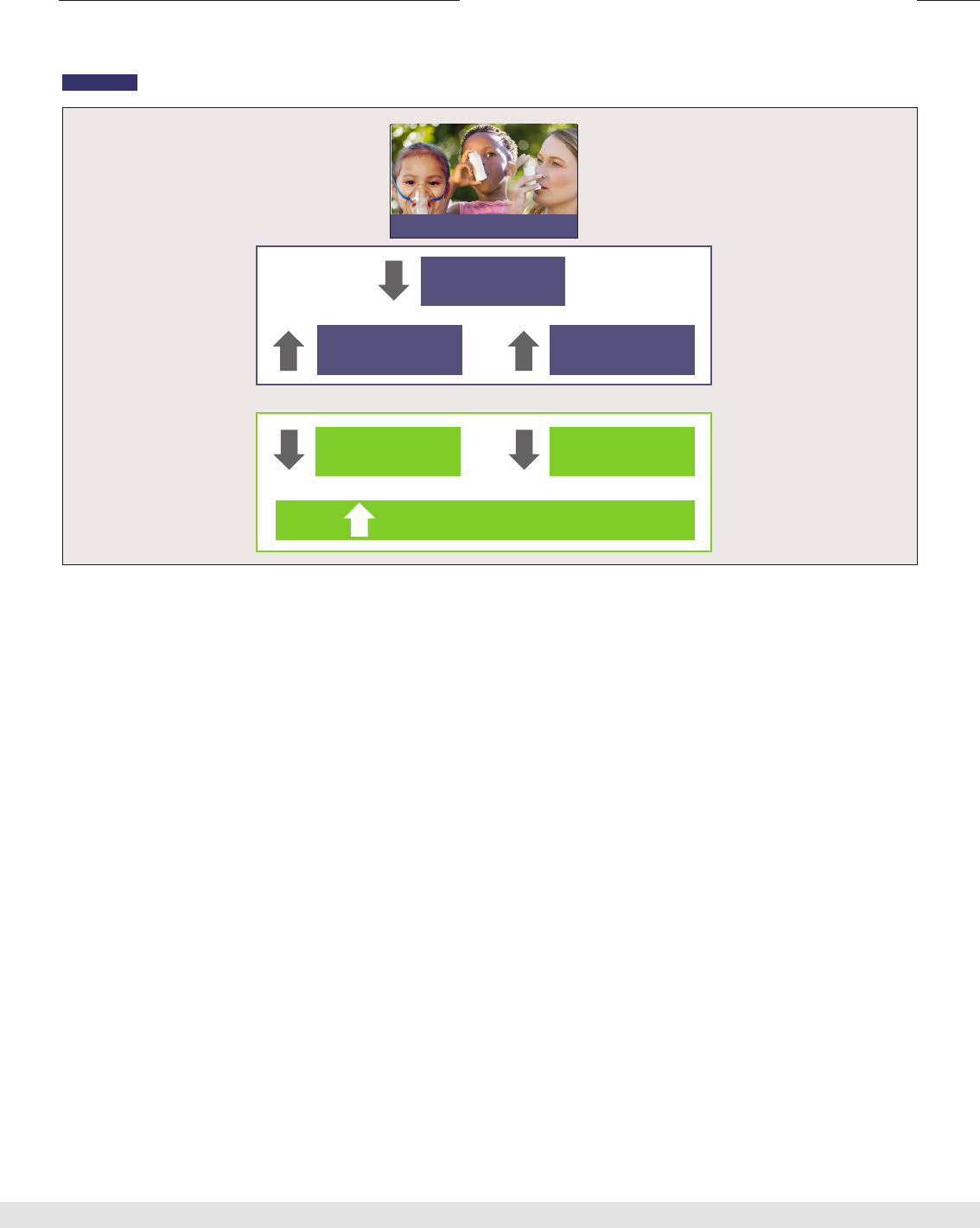

FIGURE 2 An individualized plan, including environmental control, improves asthma symptoms

22

An individualized self-management plan decreased rescue inhaler use and nighttime awakenings and increased quality of life (QoL) among

adults with asthma.

Adapted from: Janson et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(4);840-846.

Indoor and

Outdoor Allergens

Inhaler

Technique

Medication

Adherence

Rescue Inhaler

Use

Nighttime

Awakenings

Increased Quality of Life

ACTIONS

RESULTS

testing “improves the accuracy of an assessment of allergic

status based on patient opinion or a structured allergy his-

tory alone.”

25

Carefully performed skin testing and modern

standardized in vitro testing have excellent specicity and

sensitivity in the setting of a clinical history suggestive of

allergic disease. ese tests are not meant to be screening

tests for large populations but rather to conrm or exclude

the diagnosis of allergic triggers in the setting of clinically

relevant symptoms.

How do I obtain the clinical history to suggest a

need for testing?

Several questionnaires are available to facilitate the assess-

ment of allergy history and to assist parents and patients,

with the highest priority for those with high asthma bur-

den as identied in the previous article: frequent exacer-

bations, high symptom burden, step-4 or step-5 asthma

therapy, and for preschool children when parents want

to better understand the risk of continuing asthma. e

Asthma APGAR

26

tool combines an asthma “control score,”

a review of asthma medication adherence, patients’ per-

ception of their response to current therapy, and a short

list of common triggers (FIGURE 4). Question 4 of the

Asthma APGAR system is designed to begin a conversation

with patients and families regarding potential aeroallergen

sensitization. NAEPP guidelines also list questions that cli-

nicians can use to elicit a history.

3

Even without a specic asthma tool, 2 questions may

help initiate this important conversation:

• Do you know what is triggering your asthma, like

smoke, allergies, or cold air?

• Have you had any type of allergy testing in the past?

When the history is suggestive, it is appropriate to proceed

to allergen-specic testing.

What testing is available?

Skin testing, either skin prick or intradermal testing, is typi-

cally performed by an allergy specialist. Another method of

assessing sIgE sensitization is with in vitro diagnostic test-

ing. NAEPP guidelines present the advantages of the 2 types

of testing (TABLE 2).

3

Opinions on the comparative specic-

ity and sensitivity of skin testing and in vitro testing vary. In

general, they are comparable.

Patient

S18

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

STEP 2: ALLERGEN EXPOSURE IN DAILY PRACTICE

]

FIGURE 3 History plus diagnostic testing improves diagnostic accuracy

25

Diagnoses based on history alone (purple bars) tended to overestimate the occurrence of allergen sensitization. The history conrmed by

diagnostic IgE testing (blue bars) improved the accuracy of allergic status assessment.

Smith, el al. Is structured allergy history sufcient. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009. 123 646-50.

!"#$%&#'()'*&+$,&$+"-'./#&(+0'1#'./#&(+0'23-'4/253(#&/,'6"#&/35

80

60

40

100

20

0

87%

53%

76%

54%

70%

40%

46%

37%

37%

15%

Dust

Mite

Grass

Pollen

Tree

Pollen

Cat

Dog

Results of Structured History vs History and Diagnostic Testing

History

History & Allergy Test Results

% of Patients

Which test do I order?

e American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

Specic IgE Test Task Force provides guidance regarding the

use of allergy testing.

ACAAI/AAAAI Joint Task Force Recommendation

Because most allergic patients are sensitized to multiple

allergens, the task of determining which ones are of major

importance is not a simple task. Because exposure to mul-

tiple allergens to which a patient is sensitized is likely to cre-

ate a synergistic effect, optimal management may require

identication and management for each of the relevant

allergens. Panels of tests designed for specic seasons and

geographical locations are available for this purpose.

27

e availability of preselected allergen proles greatly

simplies the task of choosing allergens for testing. For skin

testing, the allergist performing the testing is likely to use a

battery of common allergen substrates. For in vitro testing,

regional respiratory proles are available that include aller-

gens typical of the geographic region or those known to be

associated with allergic asthma. Including key regional aller-

gens maximizes test eciency without compromising the

utility of test results.

27

How do I interpret test results?

Skin-testing results are interpreted by the clinician supervis-

ing the testing. e referring physician or clinician should

receive a report outlining the allergens tested and the results

(positive or negative), based on the response to the allergen

in millimeters and compared to positive and negative con-

trols. Results can be used to guide avoidance or exposure

reduction, consideration of immunotherapy, and reassur-

ance when testing is negative.

In vitro testing is also used to conrm the history and to

guide therapy, which includes environmental control, aller-

gen avoidance and, if neither is possible or sucient, to con-

sider pharmacotherapy or immunotherapy. erefore, the

interpretation is based on evidence of sensitization (yes or

no). Sharing test results with patients can help them under-

stand the nature of their sensitization and target allergen-

control eorts. Similarly, sIgE test results are useful for rul-

ing out sensitization, sparing patients the eort and cost of

avoiding allergens that are not causing their symptoms.

S19

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

STEP 2: ALLERGEN EXPOSURE IN DAILY PRACTICE

]

FIGURE 4 Asthma APGAR questionnaire

26

Please circle your answers:

1. In the past 2 weeks, how many times did any breathing problems (such as asthma) interfere with your

ACTIVITIES or activities you wanted to do?

Never ( 0 ) 1 – 2 times ( 1 ) 3 or more times ( 2 )

2. How many DAYS in the past 2 weeks did you have shortness of breath, wheezing, chest tightness,

cough or felt you should use your rescue inhaler?

None ( 0 ) 1 – 2 DAYS ( 1 ) 3 or more DAYS ( 2 )

3. How many NIGHTS in the past 2 weeks did you wake up or have trouble sleeping due to coughing,

shortness of breath, wheezing, chest tightness or get up to use your rescue medication?

Never ( 0 ) 1 – 2 NIGHTS ( 1 ) 3 or more NIGHTS ( 2 )

4. Do you know what makes your breathing problems or asthma worse?

Yes No Unsure

• Please circle things that make your breathing problems or asthma worse

Cigarettes Smoke Cold Air Colds Exercise Dust Dust Mites

Trees Flowers Cats Dogs Mold Other:______________

• Can you avoid the things that make your breathing problems or asthma worse?

Seldom Sometimes Most of the times

5. List or describe medications you’ve taken for breathing problems or asthma in the past 2 weeks:

Remember you may use Nasal, Oral, or Inhaler medications.

Breathing or Allergy

Medication

When Taken? Reasons for taking

medication:

Reasons for not taking

medication:

Daily As needed

Daily As needed

Daily As needed

Daily As needed

6. When I use my breathing or asthma medication I feel?

Worse No Different A Little Better A Lot Better

A = Activities

P = Persistent

G = triGGers

A = Asthma medications

R = Response to therapy

P = Asthma Plan

L = Lung fuction

U = Use of inhaler

S = Steroids

Asthma APGAR

A

P

G

A

R

S20

SEPTEMBER 2018

[

STEP 2: ALLERGEN EXPOSURE IN DAILY PRACTICE

]

FIGURE 5 illustrates how sIgE results may be reported.

Specic IgE values >0.10 kU

A

/L indicate sensitization;

increasing values have been correlated with increased prob-

ability of symptoms. Ranking positive results from high to low